Abstract

Background:

Iron supplementation is a chief component in prenatal care, with the aim of preventing anemia; however, extreme maternal iron status may adversely affect the birth outcome. Given the negative consequences of high maternal iron concentrations on pregnancy outcomes, it seems that iron supplementation in women with high hemoglobin (Hb) should be limited.

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to examine the effect of iron supplementation on iron status markers in pregnant women with high Hb.

Patients and Methods:

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 86 pregnant women with Hb > 13.2 g/dL and ferritin > 15 μg/l in the 16th - 20th week of pregnancy were randomized into experimental and control groups. From the 20th week until the end of pregnancy, the experimental group received one ferrous sulfate tablet containing 50 mg of elemental iron daily, while the control group received a placebo. Hb and ferritin levels at 37 - 39 weeks of pregnancy were evaluated and compared. In addition, after delivery the birth weight was measured in two groups and compared.

Results:

There were statistically significant differences between the two groups in Hb (p = 0/03) and ferritin (p = 0/04) levels at the end of pregnancy, but the incidence of anemia exhibited no difference in either group (p < 0/001). In addition, the mean of birth weight in experimental group and control group were 3391/56 ± 422, 3314/06 ± 341, respectively and it was not significant difference (p = 0.2).

Conclusions:

Not using iron supplementation did not cause of anemia in women with Hb concentrations greater than 13.2 g/dL during pregnancy; thus, the systematic care and control of iron status markers without iron supplementation is recommended for these women.

Keywords: Pregnancy; Iron, Ferritin; Hemoglobin; Birth Weight

1. Background

During pregnancy, the increase in plasma volume exceeds the increase in red cell volume; this causes a physiological hem dilution resulting in reduced hemoglobin (Hb) concentration (1). In a normal pregnancy without iron supplementation, maternal Hb has been found to fall from an average of between 12.5 - 13.0 g/dL to an average of 11.0 - 11.5 g/dL (2). Based on the world health organization (WHO) documents, it is estimated that more than 40% of pregnant women suffer from anemia, which is due to iron deficiency anemia about half of the time (3). Thus, in the recently published guidelines by the WHO, 30 - 60 mg of elemental iron supplementation is advised for all pregnant women (4). However, excessive iron consumption might lead to an increase in Hb levels and blood viscosity (5-10). This condition results in poor placental blood transfusion and adversely affects birth outcome such as preterm delivery, low birth weight (LBW), intra-uterine growth retardation (IUGR), postnatal growth retardation, low fetal head circumference, preeclampsia, and maternal hypertension, as well as fetal and early neonatal death, neurological and skeletal abnormalities, abnormal lung development, and even prenatal mortality (5, 6, 9-12). Moreover, it is clear that oral iron consumption may be unpleasant due to increasing gastrointestinal complications such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain. and constipation. In addition, some studies have confirmed that it can reduce intestinal absorption of some trace elements such as zinc and copper (13, 14). Given these considerations, it has been suggested that iron supplementation should not be used for all pregnant women. Instead, it is better to prescribe iron supplementation only if the Hb concentration falls below 10.0 g/dL (14). At the same time, there is still a lot of conflicting information about iron supplementation during pregnancy (15). Considering the negative consequences of extreme maternal iron status on pregnancy outcomes, it seems that iron supplementation in women with high Hb should be limited.

2. Objectives

Due to complications resulting from iron consumption, we aimed to examine the effect of iron supplementation on maternal iron markers and birth weight in pregnant women with high Hb levels.

3. Patients and Methods

Our study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial (RCT registration code: IRCT2013020612383N1) carried out from May 2012 to July 2013 with 86 healthy pregnant women receiving prenatal care at two prenatal clinics in Ardabil, northwest of Iran. These clinics are the only major governmental prenatal clinics in Ardabil, such that most of the pregnant women from different areas of the city are referred to them. The samples were selected from these centers using the convenience sampling method based on ɑ = 0.05, S = 11.17, and d = 2.36 (Equation 1, sample size formula).

| (1) |

We used high Hb and serum ferritin in pregnancy as the chief criteria for sampling. Participants were all in the 16th–20th week of pregnancy, and all had a Hb concentration greater than 13.2 g/dL and serum ferritin levels above than 15 μg/L (according to the centers for disease control (CDC) and prevention recommendations) (16). Hb concentration and serum ferritin levels were evaluated twice during the study, before the intervention and at end of pregnancy (37 - 39 weeks). To increase the reliability of the laboratory results, all of the blood samples were evaluated in one specific laboratory by one trained person where the laboratory equipment was calibrated. The complete blood count was measured with an automatic cell counter (Hycell, France) and serum ferritin was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ORG5Fe, Bngomtak, Germany). Inclusion criteria were a maternal age of 18 - 35 years, no medical disease, a body mass index (BMI) of 19.8 - 26 kg/m2, an Hb level more than 13.2 g/dL and ferritin level more than 15 μg/L, and having a singleton pregnancy with 16 - 20 weeks gestational age (GA). BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (17), while GA was based on a reliable, self-reported estimate of last menstrual period (LMP) or an ultrasound done early in pregnancy if LMP was unknown. When both estimates were available and were within 14 days of one another, we used the LMP to estimate GA. When the difference in estimates exceeded 14 days, we used the ultrasound (1). Exclusion criteria were smoking or having a disease related to polycythemia, such as asthma or chronic hypertension, renal disease, malignancy, or a known blood disorder. To allow for follow-up loss, 86 women were enrolled and randomized. Simple randomization from a table of random numbers was used to assign the women to the iron supplementation group (experimental group) or placebo group (control). The experimental group received one ferrous sulfate tablet containing 50 mg of elemental iron daily, while the control group received a placebo. Because iron supplementation was expected to be necessary after delivery and during the breastfeeding period, and to consider ethical concerns in this regard, all women received 50 mg of elemental iron daily for 3 months after delivery as routine postnatal care. The project was approved by the institutional ethical committee. Informed consent was obtained from all women and the study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. All mothers were followed up for the evaluation and comparison of changes in Hb and ferritin levels at the end of pregnancy (37 - 39 weeks of gestation). In the case of diagnosed anemia (≤ 11 g/dL) (16), iron supplementation was initiated and continued until delivery. After delivery, infants' weight was measured using Sea scale (accuracy: 10g). During the study (after randomization), 22 participants were excluded for different reasons, such as preterm delivery (n = 5), vaginal bleeding (n = 5), anemia (n = 2), preeclampsia (n = 3), and loss to follow-up (n = 7). Thus, data from 64 of pregnant women were analyzed and rechecked by two researchers. Finally, we used the confirmation of an associated specialist for assurance. In advance of the study, a computer randomization program was used to assign participants to either the intervention or control group. Due to carefully planned follow-up, there were no missing values. Normal distribution was checked using the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test. The independent t-test was used to compare variables between the two groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

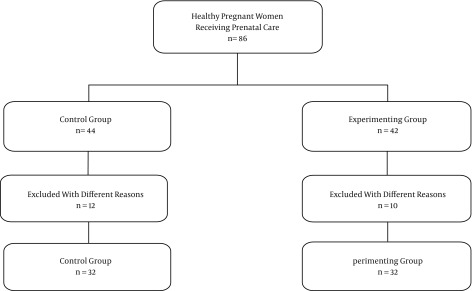

During the study of 86 pregnant women, 22 dropped out for different reasons, as mentioned above (Patients and Methods section). Thus, data from 64 pregnant women were used for statistical analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sampling Diagram.

The mean maternal age and BMI were 26.11 ± 5.13 and 23.9 ± 2.32, respectively. In addition, 50% of women were nulliparous and 81.3% were housewives. There were no significant difference between the experimental and control groups in terms of maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity, or Hb and ferritin levels at the onset of the trial (Table 1). After the intervention, at the end of pregnancy, Hb and ferritin levels were determined and compared; also the birth weight was measured and compared after delivery. The mean Hb concentration was 12.05 ± 0.9 in the experimental and 11.94 ± 0.6 in the placebo group; this different was significant (P = 0.03) but there was not significant different between 2 groups in the mean of birth weight (P = 0.2) (; Table 2). Although four pregnant women in both groups were anemic (Hb < 11 g/dL) at the end of pregnancy, none of them had Hb less than 10 g/dL, and this difference was not significant between the iron supplementation and placebo groups. Comparing these results with the CDC criteria to define anemia during the third trimesters of pregnancy, we concluded that anemia had not occurred even though the women had not consumed iron supplementation during pregnancy. In addition, the Hb concentrations of one pregnant woman in the placebo and two pregnant women in the experimental group were greater than 13.2 g/dL; this difference was not significant (Table 3).

Table 1. Demographic and Obstetric Characteristics of the Participants Before the Interventiona.

| Iron Supplementation Group | Placebo Group | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, y | 26.59 ± 5.26 | 25.63 ± 5.04 | 0.7 |

| BMI, kg/m 2 | 24.12 ± 2.17 | 23.68 ± 2.47 | 0.1 |

| Parity | 1.68 ± 0.8 | 1.65 ± 0.7 | 0.2 |

| Hb level, g/dL | 13.69 ± 0.44 | 13.57 ± 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Ferritin level, μg/L | 33.93 ± 13.72 | 37.05 ± 16.86 | 0.1 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass building; Hb, hemoglobin.

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

Table 2. Levels of Hemoglobin and Ferritin in the Iron Supplementation and Placebo Groups at the End of Pregnancya.

| Iron Supplementation Group | Placebo Group | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hb level, g/dL | 12.05 ± 0.9 | 11.94 ± 0.65 | 0.03 |

| Ferritin level, μg/L | 28.5 ± 9.3 | 27.22 ± 12.96 | 0.04 |

| Birth weight | 3391/56 ± 422 | 3314/06 ± 341 | 0.2 |

Abbreviations: Hb, hemoglobin.

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

Table 3. Number of Pregnant Women with Different Levels of Hemoglobin in the Experimental and Control Groups at the End of Pregnancya.

| Hb Level, g/dL | Iron Supplementation Group | Placebo Group | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 10 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 10 - 13.2 | 31 (96.87) | 30 (93.75) | NA |

| > 13.2 | 1 (3.13) | 2 (6.25) | NA |

Abbreviations: Hb, hemoglobin.

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the effect of iron supplementation on iron status markers and birth weight in pregnant women with high Hb levels. According to some studies, iron status can be predicted among women of childbearing age using the complete blood count test (18), but we also used ferritin level as the best iron status marker to increase the reliability of our study. We found a significant difference between both ferritin and Hb levels in the experimental and control groups at the end of pregnancy. This different was not significant before the intervention. No participants in either the experimental or control group had Hb < 10 g/dL. Previous studies confirmed that Hb greater than 13.2 g/dL increases adverse pregnancy outcomes; thus, we chose this cut-off level as a high level of Hb in pregnancy (2, 19-21). Our findings are in accordance with a report by Steer from 2013 (14). In our study, there were significant differences in Hb and ferritin levels at the end of pregnancy in the iron supplementation group and the placebo group, but the incidence of anemia was similar in both groups, wherein mild anemia was observed in a few women. These findings of this research are in accordance with those of Ziaei et al. (7). Mei et al. revealed that iron supplementation of non-anemic women during pregnancy can affect the iron status later in pregnancy; however, they did not observe this effect during the perinatal period (22). However, Roberfroid et al. claimed that iron supplementation of non-anemic pregnant women might have some benefits. For instance, they stated that even a low dose of iron supplementation of non-anemic mothers during pregnancy can increase children’s birth weight. Moreover, they found that during pregnancy, Hb concentrations decreased even in pregnant women without anemia (23). Although in our study the birth weight in iron supplementation group was more than placebo group, this different was not significant. Perhaps it is needed to study it in the large sample in future. Gonzales et al. conducted a large study in which changes of Hb concentration during pregnancy were measured in 379,816 non-anemic pregnant women. They found that Hb concentrations in most of the non-anemic pregnant women had not changed significant at the end of pregnancy, and moderate/severe anemia was observed only among 2.8% of those women. Furthermore, they revealed that the risk of anemia at the end of pregnancy in non-anemic women diagnosed early during the same pregnancy increased following higher gestational age at the second measurement of Hb, BMI < 19.9 kg/m2, living without a partner, fewer than five antenatal care visits, first parity, multiparty, and preeclampsia (24). A meta-analysis by Haider et al. showed no significant difference of maternal anemia at the time of delivery between mothers who were anemic and non-anemic women during the first trimester (25). In conclusion, our trial suggests that individual iron prophylaxis according to iron status is preferred to routine iron prophylaxis in pregnant women. Since we did not evaluate not using iron supplementation on pregnancy outcomes and the postpartum period, it is suggested that this effect should be investigated in the future studies. Our study had some strengths and limitations. Some studies investigated the correlation of high Hb concentration and pregnancy outcomes; however, to our knowledge, none of these studies have investigated the effect of not using iron supplementation in non-anemic pregnant women on the incidence of anemia near delivery. In addition, none of these articles measured ferritin level at the time of delivery in these women. However, due to the low sample size in this study, we cannot extend our results. Therefore, it is recommended that similar studies should be conducted with a larger sample size in relation to this issue.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the women who participated in this study. We also appreciate the support of Islamic Azad University, Ardabil branch.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Leila Alizadeh analyzed data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. Leili Salehi assisted in writing the first draft of the manuscript.

Funding/Support:This study was supported by Islamic Azad University, Ardabil branch.

References

- 1.Bodnar LM, Siega-Riz AM, Arab L, Chantala K, McDonald T. Predictors of pregnancy and postpartum haemoglobin concentrations in low-income women. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(6):701–11. doi: 10.1079/phn2004597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasmussen S, Bergsjo P, Jacobsen G, Haram K, Bakketeig LS. Haemoglobin and serum ferritin in pregnancy--correlation with smoking and body mass index. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;123(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daily iron and folic acid supplementation during pregnancy: WHO. Washington DC: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/elena/titles/daily_iron_pregnancy/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . Guideline: Daily Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation in Pregnant Women. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. Available from: http://www.who.int/elena/titles/daily_iron_pregnancy/en/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shobeiri F, Begum K, Nazari M. A prospective study of maternal hemoglobin status of Indian women during pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. Nutrition Research. 2006;26(5):209–13. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziaei S, Janghorban R, Shariatdoust S, Faghihzadeh S. The effects of iron supplementation on serum copper and zinc levels in pregnant women with high-normal hemoglobin. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2008;100(2):133–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziaei S, Mehrnia M, Faghihzadeh S. Iron status markers in nonanemic pregnant women with and without iron supplementation. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2008;100(2):130–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang SC, O'Brien KO, Nathanson MS, Mancini J, Witter FR. Hemoglobin concentrations influence birth outcomes in pregnant African-American adolescents. J Nutr. 2003;133(7):2348–55. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.7.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iannotti LL, Zavaleta N, Leon Z, Shankar AH, Caulfield LE. Maternal zinc supplementation and growth in Peruvian infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(1):154–60. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.1.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzales GF, Steenland K, Tapia V. Maternal hemoglobin level and fetal outcome at low and high altitudes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297(5):R1477–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00275.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilinc M, Coskun A, Bilge F, Imrek SS, Atli Y. Serum reference levels of selenium, zinc and copper in healthy pregnant women at a prenatal screening program in southeastern Mediterranean region of Turkey. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 2010;24(3):152–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaillard R, Eilers PH, Yassine S, Hofman A, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW. Risk factors and consequences of maternal anaemia and elevated haemoglobin levels during pregnancy: a population-based prospective cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014;28(3):213–26. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahan L.K., Escott-Stump S, W.B S. Food, Nutrition & Diet Therapy. 11 ed. Toronto: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steer PJ. Healthy pregnant women still don't need routine iron supplementation. BMJ. 2013;347:f4866. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krafft A. Iron supplementation in pregnancy. BMJ. 2013;347:f4399. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control. CDC criteria for anemia in children and childbearing-aged women. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 1989;38(22):400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine . Subcommittee on Nutritional Status, Weight Gain during Pregnancy, Institute of Medicine . Subcommittee on Dietary Intake, Nutrient Supplements during Pregnancy . Nutrition during pregnancy: part I, weight gain: part II, nutrient supplements. Natl Academy Pr; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alquaiz JM, Abdulghani HM, Khawaja RA, Shaffi-Ahamed S. Accuracy of Various Iron Parameters in the Prediction of Iron Deficiency Anemia among Healthy Women of Child Bearing Age, Saudi Arabia. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14(7):397–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy JF, O'Riordan J, Newcombe RG, Coles EC, Pearson JF. Relation of haemoglobin levels in first and second trimesters to outcome of pregnancy. Lancet. 1986;1(8488):992–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scanlon KS, Yip R, Schieve LA, Cogswell ME. High and low hemoglobin levels during pregnancy: differential risks for preterm birth and small for gestational age. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(5 Pt 1):741–8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00982-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alizadeh L, Raoofi A, Salehi L, Ramzi M. Impact of maternal hemoglobin concentration on fetal outcomes in adolescent pregnant women. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(8):e22761. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.19670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mei Z, Serdula MK, Liu JM, Flores-Ayala RC, Wang L, Ye R, et al. Iron-containing micronutrient supplementation of Chinese women with no or mild anemia during pregnancy improved iron status but did not affect perinatal anemia. J Nutr. 2014;144(6):943–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.189894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberfroid D, Huybregts L, Habicht JP, Lanou H, Henry MC, Meda N, et al. Randomized controlled trial of 2 prenatal iron supplements: is there a dose-response relation with maternal hemoglobin? Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(5):1012–8. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.006239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzales GF, Tapia V, Fort AL. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in second hemoglobin measurement in nonanemic women at first booking: effect of altitude of residence in peru. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:368571. doi: 10.5402/2012/368571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haider BA, Olofin I, Wang M, Spiegelman D, Ezzati M, Fawzi WW, et al. Anaemia, prenatal iron use, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3443. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]