Abstract

DNA replication checkpoint is a highly conserved cellular signaling pathway critical for maintaining genome integrity in eukaryotes. It is activated when DNA replication is perturbed. In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, perturbed replication forks activate the sensor kinase Rad3 (ATR/Mec1), which works cooperatively with mediator Mrc1 and the 9-1-1 checkpoint clamp to phosphorylate the effector kinase Cds1 (CHK2/Rad53). Phosphorylation of Cds1 promotes autoactivation of the kinase. Activated Cds1 diffuses away from the forks and stimulates most of the checkpoint responses under replication stress. Although this signaling pathway has been well understood in fission yeast, how the signaling is initiated and thus regulated remains incompletely understood. Previous studies have shown that deletion of lem2+ sensitizes cells to the inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase, hydroxyurea. However, the underlying mechanism is still not well understood. This study shows that in the presence of hydroxyurea, Lem2 facilitates Rad3-mediated checkpoint signaling for Cds1 activation. Without Lem2, all known Rad3-dependent phosphorylations critical for replication checkpoint signaling were seriously compromised, which likely causes the aberrant mitosis and drug sensitivity observed in this mutant. Interestingly, the mutant is not very sensitive to DNA damage and the DNA damage checkpoint remains largely intact, suggesting that the main function of Lem2 is to facilitate checkpoint signaling in response to replication stress. Since Lem2 is an inner nuclear membrane protein, these results also suggest that the replication checkpoint may be spatially regulated inside nucleus, a previously unknown mechanism.

Keywords: Fission yeast, DNA replication checkpoint, Lem2, Rad3, Cds1

1. Introduction

DNA replication can be perturbed by nucleotide depletion, damage on templates, or various other factors. When this occurs in a eukaryotic cell, a surveillance mechanism called DNA replication checkpoint or S phase checkpoint is activated to induce at least four protective cellular responses: (a) increased production of deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) by stimulating ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) (1–3), (b) protection of perturbed forks from collapsing (4,5), (c) suppression of the firing of late replication origins (6,7), and (d) a cell cycle delay in mitosis (8,9). These cellular responses are normally well coordinated to ensure that DNA synthesis can properly resume when perturbation diminishes so that the cell can have enough time to finish the genome duplication before undergoing mitosis. Consistent with its importance in maintenance of genome integrity and cell survival from the adverse conditions, the replication checkpoint is highly conserved from yeast to humans and defects in the pathway predispose to cancers (10,11).

In the fission yeast S. pombe, the key mediator of replication checkpoint is the protein kinase Cds1 (CHK2/Rad53) (12–14). Once activated by the sensor kinase Rad3 (ATR/Mec1), Cds1 stimulates most of the checkpoint responses mentioned above. Although the activation mechanism of the downstream kinase Cds1 is relatively clear (13,15,16), how the sensor kinase Rad3 is activated at perturbed forks remains incompletely understood. Previous studies in other model systems (17–19), most of which are in vitro studies, suggest that functional uncoupling of replicative helicase and polymerases at perturbed forks generates short stretches of single stranded DNA, which are coated with replication protein A and then recognized by Rad3 in association with its cofactor Rad26 (ATRIP/Ddc2). Another checkpoint sensor protein Rad17 (RAD17/Rad24) in association with Rfc2-5 recognizes the junction of single to double stranded DNA and loads Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 or “9-1-1” checkpoint clamp onto perturbed forks (20,21). Once loaded in close proximity to Rad3, the C-terminal tail of Rad9 in the 9-1-1 clamp is phosphorylated by Rad3. Phosphorylated Rad9 recruits other factors such as replication initiation protein Rad4 (TopBP1/Dpb11) to perturbed forks. In metazoans and S. cerevisiae, recruited TopBP1 and Dpb11 can stimulate the sensor kinases by their “ATR-activation domain” so that checkpoint signaling is amplified (19,22,23). However, this model has not been rigorously tested in vivo. For example, recent studies in yeasts have shown that in vivo, the kinase activity of Rad3 and Mec1 remains intact in rad4 or dpb11 mutants lacking the “ATR activation domain” (24–26). This suggests that activation of the sensor kinase in yeasts may not require Rad4 or Dpb11. Alternatively, the sensor kinase is activated by redundant factors (27).

To understand how checkpoint signaling occurs at perturbed forks, we have been searching for new mutants in S. pombe with defects in this process under the replication stress induced by HU. Previous genome-wide studies have discovered that individual deletion of ~130 non-essential genes sensitizes S. pombe to HU (28,29). Among these deletion mutants, lem2Δ mutant also generates cut (cell untimely torn) cells in the presence of HU (29). However, the exact mechanism why lem2Δ mutant is sensitive to HU remains unclear because defects in various cellular processes can contribute to HU sensitivity and the cut cell phenotype (30–32). Since Lem2 is an inner nuclear membrane (INM) protein important for maintaining the integrity of nuclear envelope (33), the HU sensitivity may also be caused by an INM defect exacerbated by drug treatment. While these possibilities have been excluded, this study provided several lines of evidence that HU sensitivity of this mutant is caused by diminished checkpoint signaling mediated by Rad3 during S phase. Importantly, since Lem2 is an INM protein highly accumulated in spindle pole body (SPB) (33,34), the microtubule organizing center where centromeres are attached in S. pombe, it is possible that under the stress induced by HU, the replication checkpoint signaling is spatially regulated inside nucleus.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Yeast strains and plasmids

Standard methods and genetic techniques were used for yeast cell culture (35). Yeast strains, plasmids and PCR primers used in this study are listed in supplemental Table S1, S2 and S3, respectively. The lem2+ gene was deleted by replacing the region between XhoI to NsiI sites in the open reading frame (707 bp to 1830 bp from start codon) with ura4+ marker (Fig S1). Gene-specific replacement was confirmed by colony PCRs using primers outside of integration sites, tetrad dissection of the asci generated from backcrossing with wild type strain TK48, and subsequent rescuing by Lem2 expressed from vectors. All transformations were carried out by electroporation (Gene Pulser II; Bio-Rad). The S. pombe strains were usually cultured at 30 C in YES (0.5% yeast extract, 3% dextrose and supplements) or in synthetic EMMS medium lacking appropriate supplements.

2.2. Drug sensitivity

To test drug sensitivity by spot assay, 2 × 107 cells/ml of logarithmically growing S. pombe were diluted in five-fold steps and spotted onto plates containing YE6S rich medium or the same medium with HU or methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) at the indicated concentrations. Cells spotted on the plates were also exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light (Stratalinker 2400) at the indicated doses. Plates were incubated at 30 C for 3 days and then photographed. Sensitivity of S. pombe to acute HU treatment was carried out using the previously described method (36). Briefly, after HU was added to culture at the final concentration of 15 mM, an aliquot of the culture was removed every hour during the drug treatment, diluted 1000 fold in sterile deionized water, and then spread onto plates containing YE6S medium. The plates were incubated at 30 C for 3 days to allow cells to recover. Colonies resulting from recovered cells were counted and presented as percentages relative to untreated cultures. Each data point represents an average of colonies on three plates.

2.3. Western blotting

Phospho-specific antibodies against phosphorylated Mrc1-Thr645, Cds1-Thr11, and Rad9-Thr412 were generated using chemically synthesized phosphopeptides (13,15). Rad9 and Cds1 were tagged with hemagglutinin (HA) epitope and immunoprecipitated (IPed) from whole cell lysates made by glass-bead method in the buffer containing 50 mM HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM pyrophosphate, 50 mM NaF, 60 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitors. After separation by SDS PAGE, samples were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was briefly probed with anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to confirm the loading. Immunobloting signal was detected by electrochemiluminescence using Image Reader LAS-3000 (Fuji Film). Band intensities were quantitated by ImageGauge (Fuji Film). The same blots were stripped and reprobed with phospho-specific antibodies against Rad9-Thr412 or Cds1-Thr11 for 3 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 C. Phosphorylation of Mrc1-Thr645 was directly examined in whole cell lysates prepared by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) method (15). The membranes were stripped and blotted with polyclonal antibodies against Mrc1 as the loading control. Phosphorylation of Chk1 by Rad3 was assessed by using the established mobility-shift method (37).

2.4. Flow cytometry

0.5 OD cells were collected by centrifugation and fixed in 1 ml of ice-cold 70% ethanol for ≥ 3 h or overnight at 4 C. Fixed cells were treated with 0.1 mg/ml RNase A in 50 mM sodium citrate at 37 C for ≥ 5 h and then stained with 4 μg/ml propidium iodide. The stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using Accuri C6 flow cytometer. Collected data were analyzed using software FCS Express 4Flow. FL2-A channel was used for all histograms.

2.5. Microscopy

Cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for ≥ 3 h at 4 C. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline by centrifugation at 2300 g for 30 sec., the fixed cells were stained in the same buffer containing 5 μg/ml of 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1:100 dilution of Blankophor working solution (1:1000 dilution of a stock solution, MP Biochemicals) for 5–10 min on ice. Stained cells were examined under the Olympus EX41 fluorescent microscope. Images were captured with IQCAM camera (Fast1394) using Qcapture Pro 6.0 software. Individual images were extracted into Photoshop (Adobe) to generate figures.

3. Results

3.1. The lem2 deletion mutant is highly sensitive to HU

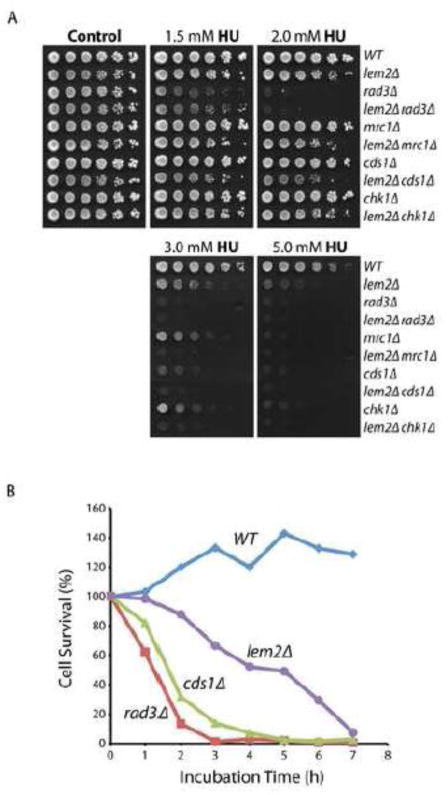

To understand how checkpoint signaling occurs at perturbed replication forks, we have been searching for new mutants in S. pombe with defects in the signaling pathways. Previous genome-wide studies have found that deletion of lem2+ sensitizes cells to HU (28,29) and causes cut cell phenotype, an indicator of aberrant mitosis, in the presence of HU (29). To investigate the function of Lem2 in HU resistance, lem2+ gene was deleted by replacing with ura4+ marker in this study (Fig S1). Sensitivity of the resulting lem2Δ mutant to HU was confirmed by standard spot assay on plates containing increasing concentrations of HU (Fig 1A). The sensitivity was found to be comparable to cells lacking Cds1 or Mrc1, two essential factors in the replication checkpoint, but less than that of rad3Δ mutant. The sensitivity was also comparable to cells lacking Chk1, the downstream kinase of the DNA damage checkpoint in S. pombe. To see whether lem2+ genetically interacts with the checkpoint pathways, the mutation was crossed into rad3Δ, mrc1Δ, cds1Δ or chk1Δ mutant for testing HU sensitivity of the double mutants. Although lem2Δ mutant grew slightly slower under normal conditions, it clearly showed an additive sensitivity to HU when combined with cds1Δ, mrc1Δ or chk1Δ, suggesting that lem2+ may function in a separate pathway with the three checkpoint genes. Interestingly, sensitivity of the lem2Δ rad3Δ double mutant was almost the same as rad3Δ single mutant (Fig 1A), suggesting that lem2+ may function in the same pathway with rad3+.

Fig 1. Deletion of lem2+ sensitizes S. pombe to HU.

(A) HU sensitivity of wild type, lem2Δ cells and cells with the indicated single or double mutations was determined by spot assay. 2 × 107 cells/ml of logarithmically growing S. pombe were diluted in five fold steps and spotted onto YE6S plates as the control or YE6S plates containing HU at the indicated concentrations. The plates were incubated at 30 C for 3 days before they were photographed. (B) Sensitivity of lem2Δ cells to acute treatment of HU. Wild type, rad3Δ, cds1Δ and lem2Δ cells were incubated in YE6S medium containing 15 mM HU. Every hour during the drug treatment, an aliquot of the culture was removed, diluted 1000 folds, and spread onto YE6S plates for cells to recover. After incubating the plates at 30 C for 3 days, colonies were counted and presented as the percentages of untreated cultures. Each data point represents an average of colonies from three plates. Note, a few tiny colonies of the HU-treated lem2Δ cell could grow up after the plates were incubated for two more days after the experiment (see text for details).

We have previously identified several mutants of Rad4 (also called Cut5) in S. pombe that are very sensitive to HU as determined by standard spot assay. However, these mutants are highly resistant to acute HU treatment (24), which is consistent with the main function of Rad4 in DNA damage checkpoint, but not the replication checkpoint pathway. To see whether lem2Δ mutant is sensitive to acute drug treatment, 15 mM HU was added to the cultures (36) and cell recovery monitored at the indicated time points (Fig 1B). Most of rad3Δ and cds1Δ cells died within ~3 h or approximately one cell cycle time after HU was added. Because Rad3 has an intrinsic activity in slowing down mitosis and functions upstream of Cds1 (38), rad3Δ mutant died slightly earlier than cds1Δ mutant. A previous study has shown that under the similar conditions, mrc1Δ cells die at about the same time as cds1Δ mutant (15). The lem2Δ mutant was found to be sensitive to acute HU treatment, suggesting that Lem2 may function in the replication checkpoint pathway. However, lem2Δ cells died more slowly than rad3Δ or cds1Δ mutant, with the greatest cell death occurring at 6 or 7 h after HU was added. Interestingly, a few tiny colonies of HU-treated lem2Δ cells could recover after plates were further incubated for two or three days (data not shown). This result showed that the cell-killing effect of HU occurs much slower in lem2Δ mutant than in the checkpoint mutants, suggesting that either a minimal checkpoint activity remains in the mutant, which is confirmed below, or the cell death is caused by a different mechanism.

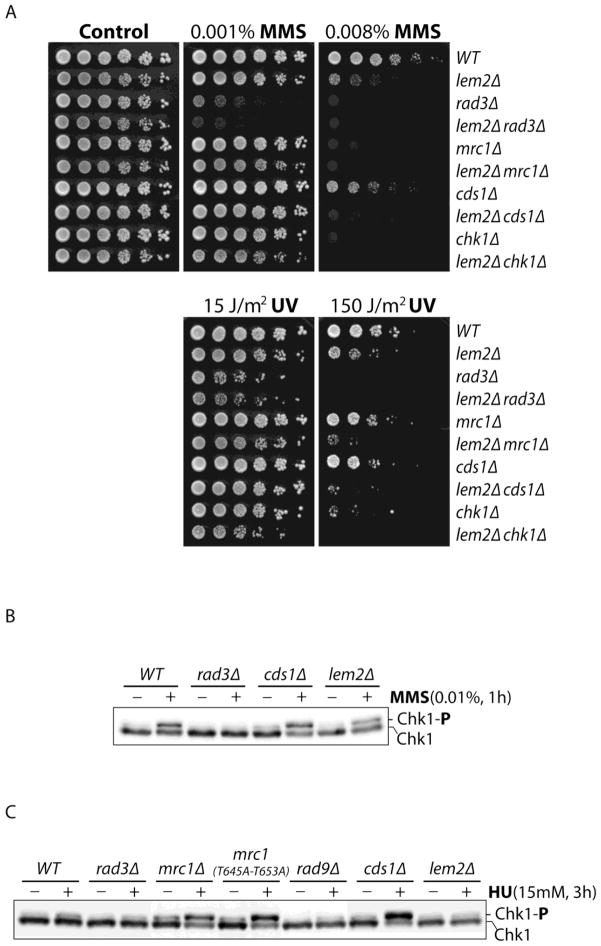

3.2. Minimal sensitivity to DNA damage

Next, the lem2Δ mutant was tested by spot assay for its sensitivity to DNA damaging agents MMS and UV (Fig 2A). It was found that the mutant was sensitive to DNA damage only when high doses of MMS or UV were used. The sensitivity was comparable to that of mrc1Δ or cds1Δ cells but less than chk1Δ cells, showing that the mutant is relatively insensitive to DNA damage. Consistent with this, checkpoint signaling from Rad3 to Chk1 in the DNA damage checkpoint pathway remained largely intact in the presence of MMS (Fig 2B). The dose response of Chk1 phosphorylation confirmed this conclusion (Fig S2). Previous studies have shown that Chk1 is activated in HU-treated cells without a functional replication checkpoint, probably by the DNA damage caused by unprotected forks (12). Thus, phosphorylation of Chk1 by Rad3 occurs in HU-treated cells without Rad9, Mrc1 or in Mrc1 mutant lacking the signaling function mediated by two redundant TQ motifs containing Thr645 and Thr653 (Fig 2C). Interestingly, under similar conditions, Chk1 was minimally phosphorylated in lem2Δ cells, suggesting that fork collapsing may occur at a low level. Alternatively, the signaling from Rad3 to Chk1 is blocked in the presence of HU (see discussion).

Fig 2. The lem2Δ mutant is minimally sensitive to DNA damage caused by MMS or UV.

(A) Sensitivity of wild type, lem2Δ, and the cells containing the indicated mutations to MMS (top panels) or UV (lower panels) was determined by spot assay as described in Fig 1A. (B) The Chk1-mediated DNA damage checkpoint response was not significantly affected in lem2Δ mutant. Wild type cells and mutant cells were treated with (+) or without (−) MMS for 1 h at 30 C. Phosphorylation of Chk1 was determined by standard mobility shift assay described under the “Experimental Procedures”. (C) Chk1 remains minimally phosphorylated in HU-treated lem2Δ mutant. Chk1 phosphorylation was assessed in cells containing the indicated mutations treated with HU at 30 C for 3 h.

3.3. Diminished signaling function of Rad3 in the replication checkpoint pathway

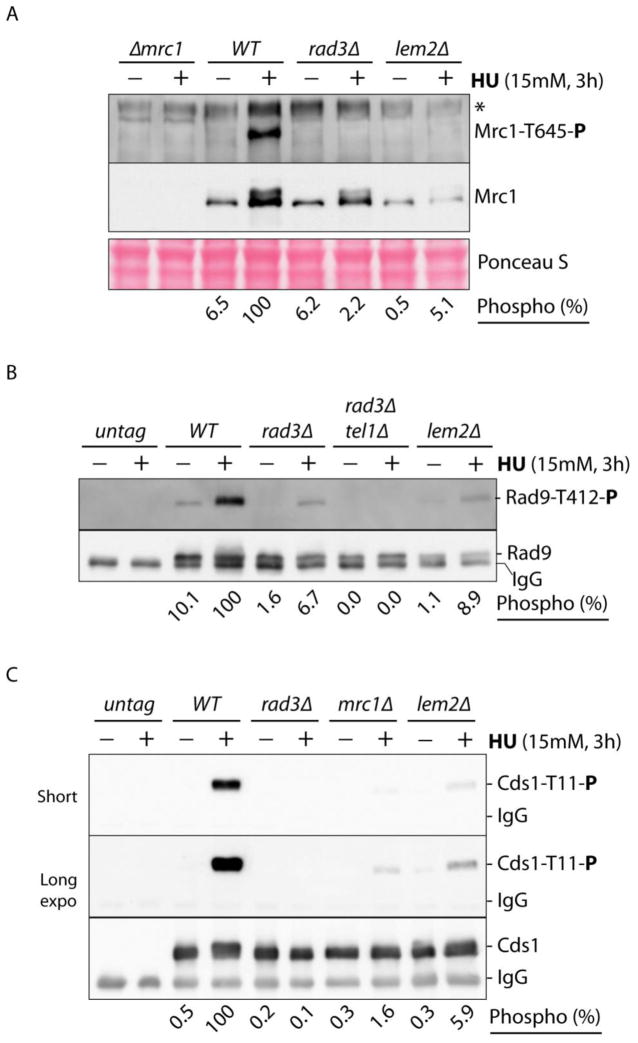

The results described above suggest that deletion of lem2+Δ may cause a defect in the replication checkpoint, not the DNA damage checkpoint, leading to the cell death in HU. To investigate this possibility, the signaling from Rad3 to Cds1 in the replication checkpoint pathway was examined by Western blotting using phospho-specific antibodies in HU-treated cells (Fig 3). As mentioned above, when DNA replication is perturbed by HU, two TQ motifs in Mrc1 are phosphorylated by Rad3 for checkpoint signaling to Cds1. Once phosphorylated, the two TQ motifs function redundantly in recruiting Cds1 to be phosphorylated by Rad3 (15). When wild type cells were treated with HU, Thr645 in Mrc1, a representative of the two redundant TQ motifs, was highly phosphorylated and the phosphorylation absolutely required Rad3 (Fig 3A). In lem2Δ cells, however, the phosphorylation was significantly reduced, consistent with the HU sensitivity observed. Quantitation results showed that ~95% of the phosphorylation was eliminated by the mutation. Interestingly, the protein level of Mrc1 was also significantly lower in HU-treated lem2Δ cells, which may explain the reduced phosphorylation. However, since Mrc1 is transcriptionally regulated by the replication checkpoint in HU (39), it is more likely that the decreased Mrc1 level is caused by diminished checkpoint signaling (see below).

Fig 3. Rad3-mediated signaling in the replication checkpoint pathway was significantly compromised in lem2Δ cells.

(A) Wild type cells and cells lacking Mrc1, Rad3 or Lem2 were incubated in YE6S medium with (+) or without (−) HU at 30 C for 3 h. The cells were collected for preparing whole cell lysates. After separation in SDS-PAGE, phosphorylation of Mrc1-Thr645 by Rad3 was examined by Western blotting using phospho-specific antibodies (upper panel). Asterisk denotes cross-reactive materials. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with polyclonal antibodies against Mrc1 (middle panel). A section of Ponceau S-stained membrane is shown as the loading control (bottom panel). Phosphorylation of Mrc1-Thr645 in wild type and mutant cells was quantitated and shown as percentages of that in HU-treated wild type cells (bottom). (B) Rad9 was tagged with HA at the N-terminus and expressed from endogenous locus in cells lacking Lem2 or the indicated checkpoint proteins. After cells were treated with HU for 3 h, extracts were made from equal numbers of the cells. Rad9 was IPed with anti-HA antibody from the cell extracts. After separation by SDS-PAGE, phosphorylated Rad9-Thr412 was detected by Western blotting using phospho-specific antibodies (upper panel). Untagged cells were used as the control for HA-specific IPs (two lanes on the left). The membrane was striped and reprobed with anti-HA antibody to reveal Rad9 (lower panel). Relative levels of the phosphorylation in wild type and mutant cells are shown on the bottom. (C) Cds1 was tagged with HA epitope at the C-terminus and expressed at cds1+ genomic locus in wild type cells or cells lacking Lem2, Mrc1 or Rad3. After HU treatment, phosphorylation of Cds1-Thr11 was assessed in IPed Cds1 by Western blotting (top two panels). Short and Long indicate different exposure times of the same blot. Loading of Cds1 was examined by blotting the same membrane with anti-HA antibody (bottom panel). Relative levels of phosphorylation are shown on the bottom.

Under HU-induced replication stress, Thr412 in the C-terminus of Rad9 in 9-1-1 complex is also phosphorylated by Rad3 (40) and by a mechanism that remains incompletely clear, phosphorylated Rad9 promotes Cds1 phosphorylation by Rad3 (Fig. 3B). Tel1, the second sensor kinase in S. pombe, which is not required for cell survival in HU, also phosphorylates Rad9. However, double deletion of Rad3 and Tel1 completely eliminated the phosphorylation. Like that in Mrc1, phosphorylation of Rad9 was also significantly reduced in lem2Δ cells to the level almost similar to that in tel1Δ cells, suggesting that most of the Rad3 dependent phosphorylation of Rad9 was eliminated. Since Rad9 is not well separated from the antibody used for IP, the protein level of Rad9 is difficult to be assessed. To confirm the results, the experiment was repeated multiple times and all results were essentially the same. In the time course study of Rad9 phosphorylation (see Fig 4A, lower panels), the samples were analyzed in a longer gel for better separation and the results clearly showed that although Rad9 level was lower in the mutant cells, the Rad3 dependent phosphorylation was significantly affected (see below). We have previously shown that the protein level of Rad9 is dependent on functional checkpoint pathways (41). It is possible that similar to Mrc1, the lower level of Rad9 is due to the checkpoint defect in the mutant. Interestingly, although Rad9 level is lower, the signaling from Rad3 to Chk1 in the DNA damage checkpoint, which requires Rad9 and its phosphorylation, remains intact in the mutant (Fig 2B).

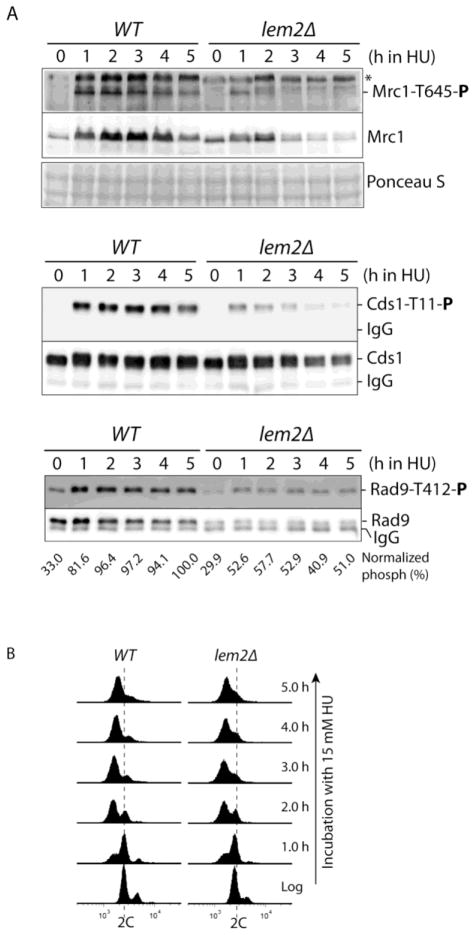

Fig 4. Time course study of the checkpoint defect during HU treatment.

(A) HU was added to cultures containing wild type or lem2Δ cells endogenously expressing HA-tagged Cds1 or Rad9. Every hour during the drug treatment, equal numbers of cells were removed from the cultures for assessing the phosphorylation of Mrc1-Thr645 (upper panels), Cds1-Thr11 (middle panels) and Rad9- Thr412 (lower panels) as described in Fig 3. Rad9 samples were analyzed in a longer gel in this experiment for better separation of the protein and IgG antibody. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of the cell cycle changes in wild type (YJ374, left column) and lem2Δ strains (YJ1364, right column) during HU treatment. Similar flow cytometry data were obtained with strains YJ865 and YJ1366 that were used for examination of Rad9 phosphorylation (not shown).

In S. pombe, the major mediator of the replication checkpoint Cds1 is activated by a two-stage mechanism (13,15,41). In the first stage, Cds1 is recruited by phosphorylated Mrc1 to be phosphorylated by Rad3 at Thr11 residue. In the second stage, phosphorylated Cds1-Thr11 promotes homodimerization of two inactive Cds1 molecules, which facilitates the autophosphorylation of Thr328 in the activation loop of the kinase domain. Phosphorylation of Thr328, which is suppressed by autoinhibitory C-terminus under normal conditions, directly activates Cds1. Because phosphorylation of Cds1-Thr11 by Rad3 primes autoactivation of the kinase, it has been used as a reliable marker for Cds1 activation (41,42). As shown in Fig 3C, phosphorylation of Cds1-Thr11 was significantly increased in HU-treated wild type cells and the phosphorylation was dependent on Rad3 and facilitated by Mrc1. Since phosphorylation of both Mrc1 and Rad9 was affected, phosphorylation of Cds1-Thr11 was also significantly decreased in the mutant as expected (Fig 3C). However, Lem2 may also directly facilitate Cds1 phosphorylation by Rad3 (see discussion). Interestingly, unlike Mrc1 and Rad9, the protein levels of Cds1 and Chk1 are similar to that in wild type cells (Fig 3C and 2C). Quantitation of Cds1 phosphorylation showed that only ~6% of the phosphorylation remained in HU-treated lem2Δ cells (Fig 3C, bottom).

3.4. Defects in initiation and maintenance of checkpoint signaling during HU treatment

Checkpoint signaling is a dynamic process involving initiation, maintenance, and diminishing stages during HU treatment. To investigate the checkpoint defect further, Rad3 dependent phosphorylation of Mrc1, Cds1 and Rad9 was monitored during the time course of a long-term HU treatment (Fig 4). After HU was added to the culture at 15 mM for 1 h, phosphorylation of Mrc1, Cds1 and Rad9 in wild type cells was near or reached the maximal level (upper, middle and lower panels in Fig 4A). In fission yeast, DNA replication starts before two daughter cells physically separate. As a result, only a small fraction of cells were arrested with 1C DNA content after 1 h treatment with HU (Fig 4B). As more cells were arrested in S phase, phosphorylation of the three proteins was maintained at this level for ~3 h. After ~5 h, Rad3 dependent phosphorylation, particularly the phosphorylation of Mrc1 and Cds1, began to decrease, consistent with slow progression of cells into late S phase or diminishing drug effects. In lem2Δ cells, however, phosphorylation of Mrc1 and Cds1 was significantly reduced during the first 2 h in HU and further decreased during the rest of drug treatment. The phosphorylation became almost undetectable after 4 to 5 h although the cells were still arrested in S phase (Fig 4B, right column). Interestingly, at early stage of the drug treatment, the protein level of Mrc1 was slightly lower or similar to that in wild type cells. As the drug treatment continued for more than 3 h, Mrc1 level began to decrease significantly, consistent with the results shown in Fig 3A. Because expression of Mrc1 is regulated by Cdc10, the transcription factor required for G1/S transition and a target of activated replication checkpoint (39), it is possible that defect in checkpoint signaling causes the Mrc1 level to decrease in lem2Δ cells. However, decreased Mrc1 level may not be the only explanation for diminished Mrc1 phosphorylation. We have recently found that in our newly screened hus41 mutant (see below) that although Mrc1 level was lower, the phosphorylation remained the same as in wild type cells, suggesting that only a fraction of Mrc1 molecules was phosphorylated by Rad3 in the presence of HU.

Interestingly, during the course of HU treatment, Rad9 phosphorylation was maintained at a relatively constant low level in the mutant cells although the protein level was also lower in the presence or absence of HU (Fig 4A, lower panels). As mentioned about, the low level of Rad9 may be due to the checkpoint defect as Rad9 level depends upon functional checkpoints. Since Tel1 contributes to Rad9 phosphorylation (see Fig 3B and ref. 41), most of the Rad3 dependent phosphorylation of Rad9 was eliminated by lem2 mutation even after the values were normalized with protein levels. Together, these results clearly showed that depletion of lem2+ causes a significant defect in Rad3-mediated checkpoint signaling for Cds1 activation under the replication stress induced by HU.

3.5. Defect in recovery from HU-induced S phase arrest

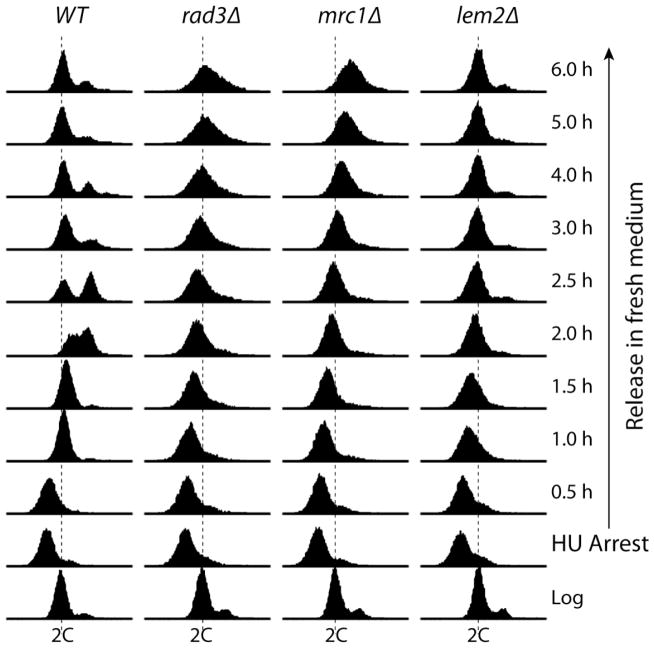

The results described above suggest that the sensitivity of lem2Δ cells to HU may be caused by the signaling defect in the replication checkpoint. However, the slow cell-killing effect of HU and potential minimal fork collapse may also suggest other possibilities. Recent studies in E. coli and S. cerevisiae showed that HU may kill the cells by generating oxidative stress (43,44). Earlier studies on the liz1 mutant in fission yeast, which encodes a pantothenate transport protein, showed that defect in pantothenate uptake can cause HU sensitivity and the cut cell phenotype (31,32). We have also found recently that HU induces G2/M, not S phase arrest in the newly screened hus41 mutant with a defect in the sterol synthesis pathway (data not shown). To further investigate the cell killing mechanism of HU in lem2Δ mutant, cell cycle analysis was performed in the context of a standard HU block and release experiment (Fig 5). When wild type cells were treated with HU for 3 h, almost all cells were arrested in S phase (Fig 5, left column). After the HU-arrested cells were released in fresh medium, they finished DNA synthesis in ~1.5 h and progressed into next cell cycle in ~2 h. Within 6 h, wild type cells had fully recovered from the arrest and returned back to normal cell cycle. In contrast, rad3Δ and mrc1Δ cells took at least 2.5 h to 3 h to “finish” the S phase after release. The broader peak in later hours after release strongly suggests that these mutants experienced a difficulty in recovering from the HU arrest. Most of lem2Δ cells were also arrested in S phase by HU although a small fraction of cells remained at G2/M (Fig 5, right column). However, similar to mrc1Δ mutant, lem2Δ mutant also took ~2.5 h to “finish” the bulk of DNA synthesis after release. Although the peaks of released lem2Δ cells were generally narrower than mrc1Δ and rad3Δ cells, the lem2Δ cells did not return to normal cell cycle even 6 h after the release, indicating a defect in recovering from the HU-induced S phase arrest.

Fig 5. The lem2Δ cells have a defect in recovering from HU-induced S phase arrest.

Logarithmically growing wild type cells or cells lacking Rad3, Mrc1 or Lem2 were incubated with 15 mM HU for 3 h (HU arrest, noted on the right). After removal of HU, the arrested cells were released into cell cycle by incubating in fresh medium. The cell cycle effects of HU were analyzed by flow cytometry following the standard protocol. The logarithmically growing cells are shown on the bottom. The time points during the release are marked on the right. Genotypes of the strains are shown on top. Dash lines indicate 2C DNA content.

3.6. Cell death resulting from the arrest in S, not G2/M phase of the cell cycle

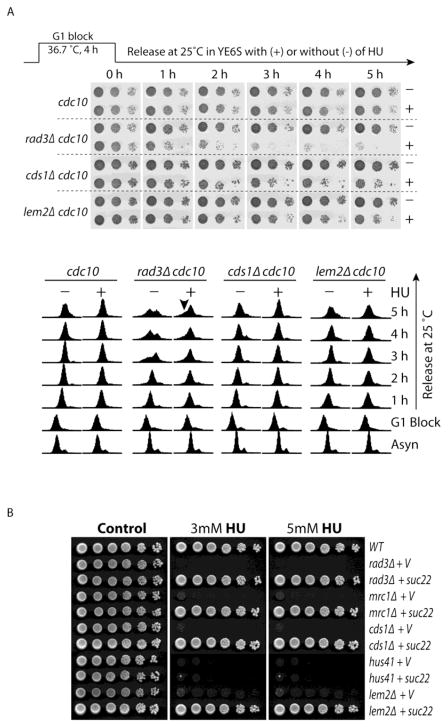

As mentioned above, we have recently found that in the presence of HU, our newly screened hus41 mutant was arrested in G2/M (data not shown), similar to that described in the liz1 mutant (31,32). When treated with HU for 3 h, a small fraction of lem2Δ cells remained in G2/M and slowly moved into S phase in the presence of HU (Fig 4B and Fig 5). This suggests a possibility, although less likely, that some of the HU-treated lem2Δ cells may die by a different mechanism involving G2/M arrest. To investigate this possibility, the mutation was crossed into cdc10-129 mutant so that the cells could be arrested in G1 by culturing at the non-permissive temperature 36.5 C for 4 h and then released into S phase at the permissive temperature 25 C in the presence or absence of HU (45). In this way, the HU effect will be limited to S phase for almost all cells in the culture. Every hour during the release from G1 arrest, equal number of cells were removed, diluted in ten-fold steps, and spotted onto YES plates for cells to recover. Comparison of the cells released in HU with that released in fresh medium allows assessment of the cell-killing effect of HU in S phase. As shown in the upper panel of Fig 6A, when cdc10 “wild type” cells were released in HU from G1 arrest, almost all cells could survive during the 5 h long release. The cell cycle analysis confirmed the G1 block and subsequent HU arrest of the released cells in S phase (Fig 6A, lower panel). Because the G1 arrested cdc10 mutant cells are elongated and may have a higher staining background, the S phase arrested cells appear to have more than 1C DNA content. As expected, while rad3Δ cdc10 cells survived well after release from the G1 arrest in the absence of the HU, most of cells died within 1 to 2 h after release into HU. The accumulated sub G1 cells in HU-treated rad3Δ cdc10 mutant (Fig 6A, short arrow in the lower panel) supports this conclusion. The cds1Δ cdc10 mutant was less sensitive to HU as the cell death became apparent in ~2 to 3 h after the G1 release, consistent with the result shown in Fig 1B. Under the similar conditions, the cell death of lem2Δ cdc10 mutant became noticeable at ~3 to 4 h after the G1 release, 1 to 2 h later than cds1Δ cells. Since almost all cells were arrested in S phase by HU in this experiment, this result clearly showed that the slow cell-killing effect of HU in lem2Δ mutant is due to S phase-specific effect, excluding the cell-killing mechanisms involving G2/M arrest. The small accumulation of G2/M cells in the HU-treated lem2Δ mutant is likely caused by a potential defect in nuclear envelope integrity.

Fig 6. The cytotoxic effect of HU on lem2Δ mutant is likely caused by the defect in replication checkpoint.

(A) Logarithmically growing cdc10-129 cells or the cdc10-129 cells lacking Rad3, Cds1 or Lem2 were arrested at G1 phase by incubating at the non-permissive temperature 36.7 C for 4 h. The G1 arrested cells were then released into cell cycle by incubating at the permissive temperature 25 C in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 15 mM HU. Every hour during the G1 release, an equal number of cells were removed from the cultures, diluted in ten-fold steps, and spotted on YE6S plates to monitor the cytotoxic effect of HU. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days for cells to recover (upper panel). The cells were also fixed at the indicated time points during the course of the experiment for cell cycle analysis by flow cytometer (low panels). Logarithmically growing cells before the G1 arrest were marked as “Asyn” on the bottom. Note, since the G1 arrested cdc10-129 cells are longer than asynchronized cells, the cells released from the G1 arrest and then blocked in S phase by HU appear to have more than 1C DNA content. The sub G1 peaks of rad3Δ cells released in HU were marked by a short arrow. (B) Overexpression of the small subunit of RNR Suc22 can rescue lem2Δ mutant similar to that in checkpoint mutants. Suc22 was expressed under the control of its own promoter from a vector. An empty vector was used as the control. A newly screened mutant hus41 is shown here as an control that HU sensitivity cannot be rescued by Suc22 under the similar conditions, indicating that the cell death induced by HU may involve a novel mechanism in this mutant (see text for details).

3.7. Overexpression of Suc22 rescues lem2Δ mutant like the replication checkpoint mutants

In the presence of HU, one of the major functions of the replication checkpoint is to stimulate RNR so that more dNTPs are produced for DNA synthesis. Suc22 is the small subunit of RNR and the major regulation target of activated replication checkpoint (46,47). Therefore, overexpression of Suc22 rescued all known mutants such as rad3Δ, mrc1Δ and cds1Δ mutants in the replication checkpoint pathway (Fig 6B). In contrast, the above mentioned hus41Δ mutant could not be rescued under the similar conditions, which is consistent with a novel cell-killing mechanism of HU involving G2/M arrest in this mutant. However, overexpression of Suc22 fully rescued lem2Δ mutant like the checkpoint mutants, confirming the checkpoint defect in lem2Δ cells.

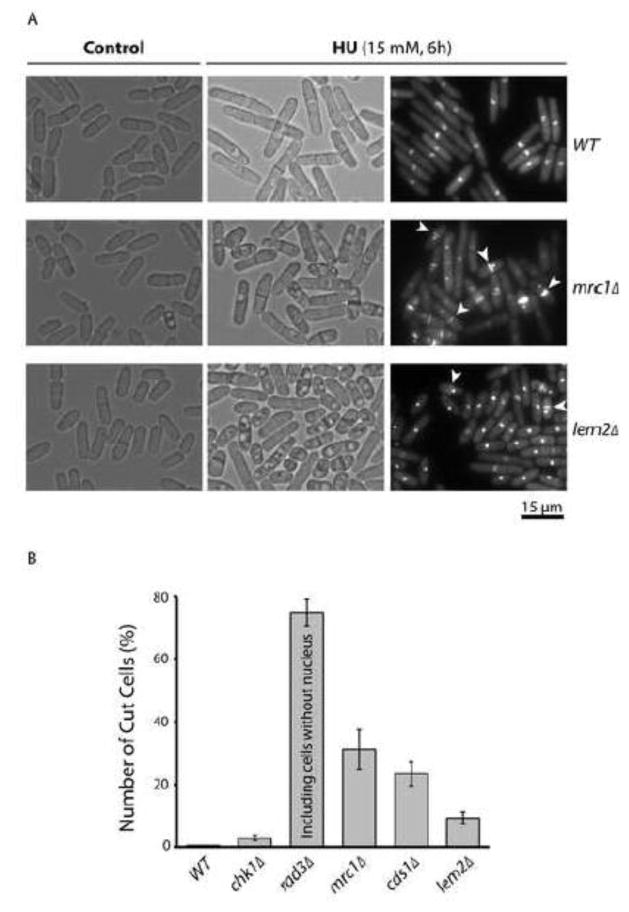

3.8. HU treatment generates “cut” cells in lem2Δ mutant

The results described above strongly suggest that the HU sensitivity of lem2Δ mutant is likely caused by the S phase checkpoint defect, not by a mechanism involving G2/M arrest. Consistent with the defect in replication checkpoint, the cut phenotype has been previously observed in HU-treated lem2Δ mutant (29). To further investigate the cell-killing mechanism of HU, lem2Δ cells were examined microscopically at various time points during HU treatment (Fig 7). When wild type cells were treated with HU for 6 h, they were dramatically elongated and most of the cells contained only one nucleus brightly stained with DAPI (Fig 7A), suggesting a functional checkpoint in arresting the cell cycle. Under the similar conditions, the nucleus in most of mrc1Δ cells was highly condensed and septum could be found in ~30% of cells with an unequal distribution of genomic DNA or the cut cells (Fig 7A, indicated by the arrows), indicating aberrant mitosis and a checkpoint defect. In the absence of HU, lem2Δ mutant behaved like wild type cells (Fig 7A, bottom left panel) and the DAPI stained nuclei were also similar to that in wild type cells (data not shown). However, most of HU-treated lem2Δ cells contained a highly condensed nucleus similar to that in mrc1Δ cells and some of the HU-treated cells clearly showed the cut phenotype. The cut cells in HU-treated lem2Δ mutant were counted and compared with that in the checkpoint mutants (Fig 7B). Most of HU-treated rad3Δ mutant had the cut cells as expected because all cells died after 6 h HU treatment (Fig 1B). Since the replication checkpoint remains largely functional in chk1Δ cells, only a small fraction of cells had the cut phenotype. However, unlike the previous report in which 88% of lem2Δ cells were found to have the cut phenotype after a 10 h treatment with HU (29), only ~10% cut cells were found in this study although the cells were treated with HU for only 6 h. This number was higher than in chk1Δ mutant but significantly lower than in cds1Δ or mrc1Δ mutant. However, it explains well the level of HU sensitivity observed in Fig 1 and the partial checkpoint defect described in Fig 3 and 4. Interestingly, under the bright field, most of the HU-treated lem2Δ cells appeared to contain vacuole-like structures similar to that in mrc1Δ mutant (Fig 7A, middle panels), suggesting that HU may cause a similar stress to both mrc1Δ and lem2Δ cells. Together, these results clearly showed that in the presence of HU, the replication checkpoint signaling was seriously compromised in lem2Δ mutant, which likely causes the cell death and the cut phenotype.

Fig 7. HU treatment generates cut cells in lem2Δ mutant.

(A) Logarithmically growing wild type and the cells lacking Mrc1 or Lem2 were examined under microscopy in bright field (three control panels on the left). After the cells were treated with HU for 6 h, the cells were examined directly in bright field (three panels in the middle) or fixed in glutaraldehyde, stained with DAPI and Blankophor, and examined by fluorescent microscopy (three panels on the right). Arrows indicate the cut cells in which genomic DNA is unequally divided by septum into two daughters. (B) The cut cells were counted in cultures containing wild type or the indicated mutant cells treated with HU for 6 h and presented as the percentages relative to the untreated cells. Note, because rad3Δ cells lack the checkpoint functions completely and HU treatment lasted for 6 h in this experiment, the cells without detectable nucleus are likely the daughters of parent cut cells and were therefore included in the cut cells. Bars indicate standard deviations.

4. Discussion

DNA replication checkpoint plays a critical role in maintaining genome integrity when DNA replication is perturbed. If undetected by the checkpoint, perturbed forks collapse, causing DNA damage or even cell death. Despite its importance, the checkpoint signaling that occurs at perturbed forks, particularly at the initiation stage, remains poorly understood. Here I show that lem2Δ mutant has a serious defect in Rad3-mediated checkpoint signaling when cellular dNTP levels are lowered by HU and this defect likely causes the cell death and aberrant mitosis (29). First, deletion of lem2+ sensitizes the cells to chronic and acute treatment with HU and the sensitivity is comparable to that of mrc1Δ and cds1Δ mutants. Second, epistasis analysis suggests that lem2+ may function in the same pathway with rad3+. Third, overexpression of Suc22, the small subunit of RNR and major downstream target of the replication checkpoint, can fully rescue the mutant similar to that in checkpoint mutants. Fourth, consistent with the previous report (29), HU treatment causes cut cells and number of cut cells is consistent with the HU sensitivity observed in this mutant. Finally, all known Rad3-dependent phosphorylations critical for checkpoint signaling are significantly compromised by the mutation. We have previously shown that when dNTP shortage occurs, activated Rad3 phosphorylates Mrc1 and Rad9, which promote the phosphorylation of Cds1 by Rad3 (41). Although phosphorylation of Cds1 by Rad3 is clearly affected in lem2Δ cells, it remains unclear whether this is a direct effect on Rad3 because elimination of the phosphorylation of Mrc1 and Rad9 may indirectly affect Cds1 phosphorylation. Nonetheless, it is clear that in the presence of HU, Lem2 functions to facilitate Rad3-mediated checkpoint signaling for Cds1 activation in S. pombe.

It is generally believed that one of the major functions of activated Cds1 is to protect perturbed forks against collapse although the mechanism remains poorly understood (4,5). Consistent with this notion, Chk1 is activated in HU-treated S. pombe lacking a functional replication checkpoint, probably by the DNA damage generated from fork collapsing. It is clear that the replication checkpoint does not function properly in lem2Δ mutant. However, Chk1 is not highly phosphorylated in response to HU. It is possible that the minimal level of Cds1 activation (Fig 3C and 4A) is high enough to protect forks from collapsing or to increase cellular dNTPs, which promotes fork progression and thus stabilizes perturbed forks under stress. Since Rad9 is poorly phosphorylated in HU-treated lem2Δ cells and the phosphorylation is required for Chk1 activation (40,41), it is also possible that the defect in Rad9 phosphorylation may indirectly affect Chk1 activation. Alternatively, depletion of Lem2 has a direct impact on Rad3 signaling to Chk1 in the presence of HU.

The minimal Cds1 activation in lem2Δ mutant may also explain why a longer exposure to HU is required for the cytotoxicity. Although aberrant mitosis clearly causes cell death of a checkpoint mutant, the DNA damage generated from collapsed forks may play an even more important role in the cell-killing process, particularly in wild type cells with intact checkpoint function. However, the exact mechanisms underlying HU-induced cell death remain unknown. HU can also kill the cell by generating oxidative stress or G2/M arrest (43,48). However, since HU arrests lem2Δ cells mainly in S phase and the mutation significantly affects the replication checkpoint signaling, the cell death is likely caused by the checkpoint defect. The aberrant mitosis in HU and the rescuing effect of overexpressed Suc22 observed in this mutant further support this conclusion.

How can Lem2, an INM protein, facilitates Rad3-mediated checkpoint signaling? It is possible that Lem2 directly affects Rad3 activity. However, directly measuring the kinase activity of endogenous Rad3 remains challenging in S. pombe (38,49,50), probably because the protein level is extremely low (51). Alternatively, Lem2 may facilitate the signaling by other mechanisms such as proper subcellular localization of key checkpoint proteins, similar to that described for Suc22 (1,47), in which Suc22 is relocalized from nucleus to cytoplasm in order to promote the formation of RNR complex and become an active enzyme. Indeed, the level of Rad9 protein is lower in the mutant under normal condition and the Mrc1 level does not properly increase in the presence of HU like that in wild type cells, suggesting the possibility of mislocalization of checkpoint proteins. Lem2 and its related INM protein Man1 are highly conserved in eukaryotes (33,34,52). Members of this protein family share a common membrane topology: two transmembrane domains that separate the proteins into the N-, C-terminal domains in nucleoplasm and a lumenal domain in nuclear envelope. These two INM proteins are not essential for vegetative growth in S. pombe but play an important role in the integrity of nuclear envelope (33). However, whether these proteins function in protein relocalization across nuclear envelope remains unknown. Interestingly, unlike Man1 that is primarily localized at nuclear envelope through out the cell cycle, Lem2 specifically accumulates at SPB during the interphase and late stage of mitosis (33,34). Because man1Δ mutant is not sensitive to HU (Fig S3), the specific nuclear localization of Lem2 may be required for its checkpoint function. Although another structurally unrelated INM protein Ima1 is also accumulated at SPB in S. pombe (34), the genome-wide studies suggest that Ima1Δ mutant is not sensitive to HU (28,29,53,54). Interestingly, we have recently found that the checkpoint function of Lem2 is specifically associated with its C-terminal domain (data not shown). It would be interesting to see whether the C-terminal domain of Lem2 can physically interact with Mrc1, Rad9 or other checkpoint proteins to facilitate their subcellular localization and the signaling functions.

In yeasts, Lem2 and Man1 perform the fundamental functions of lamina in mammalian cells (33). The importance of lamina is underscored by the observations that mutations in lamins or lamin associated proteins are linked to a series of diseases collectively called laminopathies (55). Unlike the genome organization in mammalian cells, in which small heterochromatic domains are interspersed through out the chromosomes, yeast heterochromatin is predominantly present in centromeres, telomeres, rDNA repeats and mating type loci, all of which are enriched near nuclear envelope (56,57). Although the centromeres are heterochromatin, their replication origins fire early in both yeasts (58–60). In S. pombe, the centromeric origins fire 9 min earlier than the average of all origins (61). Considering that the S phase is relatively brief in fission yeast (20 min vs. 3 h cell cycle time), the centromeric origins may represent a small set of origins that fire at the beginning of S phase. Since higher dNTP levels promote nucleotide misincorporation, the cell has to maintain continuous dNTP supplies at tightly controlled concentrations for hundreds of ongoing forks during S phase. Eukaryotic cells sense the shortage of dNTPs by replication checkpoint via slowed forks. A previous proteomic analysis showed that a single S. pombe cell contains only ~70 Rad3 molecules (51). If this number is correct and at least one Rad3 is required to sense one perturbed fork, the maximum capacity of checkpoint sensing is ~70 forks from ~35 origins. Because centromeric origins fire early, the forks generated from these origins are likely the first to be slowed by HU and thus used for checkpoint sensing.

In fission yeast, centromeres are tethered to SPB (62). Since Lem2 facilitates Rad3 signaling and accumulates at SPB at the time when DNA replication is about to occur, a hypothesis can thus be proposed in which Lem2 may facilitate checkpoint sensing of HU-slowed forks originated from centromeric origins. Since fork slowing may cause mutations, checkpoint sensing of slowed forks at heterochromatin such as centromeres may enable the cell to avoid potential detrimental mutations that may otherwise occur in gene-rich or transcriptionally active regions of chromosomes. Consistent with this hypothesis and the possibility of proper subcellular localization of checkpoint proteins, Mrc1 preferentially binds to early origins in S. pombe (63). A recent study has also shown that a fraction of ATR, the Rad3 ortholog in humans, is located at nuclear envelope for sensing the mechanical stress generated by topological transitions of replicating or condensing chromosomes at the nuclear membrane where chromatin is attached (64). However, whether the mechanic stress is generated at nuclear membrane by HU-slowed forks and thus sensed by Rad3 is completely unknown in S. pombe. Interestingly, similar to this hypothesis, the rDNA heterochromatin has been proposed previously to function as a sensor of DNA damage in S. cerevisiae (65). Further studies are needed to define the checkpoint function of Lem2.

5. Conclusion

This study shows that when treated with HU, most of lem2Δ mutant cells are arrested in S phase and all three known Rad3 dependent phosphorylations critical for the replication checkpoint signaling are seriously compromised. Because of this checkpoint defect, the mutant cannot properly recover from the HU-induced S phase arrest. This defect also explains the HU sensitivity and aberrant mitosis observed in this mutant. However, the mutant is relatively insensitive to DNA damage and the mutation does not affect much of the DNA damage checkpoint. Thus, the main checkpoint function of the nuclear membrane protein Lem2 is to facilitate Rad3-mediated signaling for Cds1 activation under replication stress.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

This study shows that in fission yeast, when DNA replication is arrested by hydroxyurea, the inner nuclear membrane protein Lem2 can facilitate checkpoint signaling. Depletion of this protein seriously compromises the signaling process, which causes aberrant mitosis and sensitizes the cell to hydroxyurea. Since Lem2 is a nuclear membrane protein, this result suggests that checkpoint signaling during S phase of the cell cycle may be spatially regulated inside nucleus, a previously unknown mechanism.

Acknowledgments

I thank Paul Russell, Tom Kelly and Shelley Sazer for sharing the yeast strains, Tom Kelly and Mike Leffak for advices, Eric Romer and two anonymous reviewers for critical reading of the manuscript. Amanpreet Singh, Andrea Gerstner and other members of the author’s laboratory are acknowledged for their help. This work was supported by NIH RO1 grant GM110132 to YJX and the start-up fund provided by Wright State University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Liu C, Powell KA, Mundt K, Wu L, Carr AM, Caspari T. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1130–1140. doi: 10.1101/gad.1090803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elledge SJ, Davis RW. Genes Dev. 1990;4:740–751. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao X, Muller EG, Rothstein R. Mol Cell. 1998;2:329–340. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabatinos SA, Green MD, Forsburg SL. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:4986–4997. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01060-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopes M, Cotta-Ramusino C, Pellicioli A, Liberi G, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M, Newlon CS, Foiani M. Nature. 2001;412:557–561. doi: 10.1038/35087613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zegerman P, Diffley JF. Nature. 2010;467:474–478. doi: 10.1038/nature09373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez-Mosqueda J, Maas NL, Jonsson ZO, Defazio-Eli LG, Wohlschlegel J, Toczyski DP. Nature. 2010;467:479–483. doi: 10.1038/nature09377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhind N, Russell P. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3782–3787. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boddy MN, Furnari B, Mondesert O, Russell P. Science. 1998;280:909–912. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stracker TH, Couto SS, Cordon-Cardo C, Matos T, Petrini JH. Mol Cell. 2008;31:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, Kramer A, Tort F, Zieger K, Guldberg P, Sehested M, Nesland JM, Lukas C, Orntoft T, Lukas J, Bartek J. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindsay HD, Griffiths DJ, Edwards RJ, Christensen PU, Murray JM, Osman F, Walworth N, Carr AM. Genes Dev. 1998;12:382–395. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.3.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu YJ, Kelly TJ. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16016–16027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900785200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murakami H, Okayama H. Nature. 1995;374:817–819. doi: 10.1038/374817a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu YJ, Davenport M, Kelly TJ. Genes Dev. 2006;20:990–1003. doi: 10.1101/gad.1406706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai Z, Chehab NH, Pavletich NP. Mol Cell. 2009;35:818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou L, Elledge SJ. Science. 2003;300:1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi JH, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Kemp M, Mason AC, Wold MS, Sancar A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13660–13665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007856107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mordes DA, Nam EA, Cortez D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18730–18734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806621105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellison V, Stillman B. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E33. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majka J, Binz SK, Wold MS, Burgers PM. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27855–27861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumagai A, Lee J, Yoo HY, Dunphy WG. Cell. 2006;124:943–955. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navadgi-Patil VM, Burgers PM. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35853–35859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807435200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yue M, Zeng L, Singh A, Xu YJ. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandhu A, Kang J, Fukunaga K, Goto G, Sugimoto K. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bastos de Oliveira FM, Kim D, Cussiol JR, Das J, Jeong MC, Doerfler L, Schmidt KH, Yu H, Smolka MB. Mol Cell. 2015;57:1124–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S, Burgers PM. Genes Dev. 2013;27:313–321. doi: 10.1101/gad.204750.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han TX, Xu XY, Zhang MJ, Peng X, Du LL. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayles J, Wood V, Jeffery L, Hoe KL, Kim DU, Park HO, Salas-Pino S, Heichinger C, Nurse P. Open Biol. 2013;3:130053. doi: 10.1098/rsob.130053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yanagida M. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:144–149. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stolz J, Caspari T, Carr AM, Sauer N. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:406–412. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.2.406-412.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moynihan EB, Enoch T. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:245–257. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.2.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez Y, Saito A, Sazer S. Nucleus. 2012;3:60–76. doi: 10.4161/nucl.18824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hiraoka Y, Maekawa H, Asakawa H, Chikashige Y, Kojidani T, Osakada H, Matsuda A, Haraguchi T. Genes Cells. 2011;16:1000–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular Genetic Analysis of Fission Yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enoch T, Carr AM, Nurse P. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2035–2046. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Limbo O, Porter-Goff ME, Rhind N, Russell P. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:573–583. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00994-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bentley NJ, Holtzman DA, Flaggs G, Keegan KS, DeMaggio A, Ford JC, Hoekstra M, Carr AM. EMBO J. 1996;15:6641–6651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ivanova T, Alves-Rodrigues I, Gomez-Escoda B, Dutta C, Decaprio JA, Rhind N, Hidalgo E, Ayte J. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:3350–3357. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-05-0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furuya K, Poitelea M, Guo L, Caspari T, Carr AM. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1154–1164. doi: 10.1101/gad.291104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yue M, Singh A, Wang Z, Xu YJ. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22864–22874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.236687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka K, Boddy MN, Chen XB, McGowan CH, Russell P. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3398–3404. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3398-3404.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davies BW, Kohanski MA, Simmons LA, Winkler JA, Collins JJ, Walker GC. Mol Cell. 2009;36:845–860. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowe LA, Degtyareva N, Doetsch PW. Mech Age Dev. 2012;133:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowndes NF, McInerny CJ, Johnson AL, Fantes PA, Johnston LH. Nature. 1992;355:449–453. doi: 10.1038/355449a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandez Sarabia MJ, McInerny C, Harris P, Gordon C, Fantes P. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;238:241–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00279553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nestoras K, Mohammed AH, Schreurs AS, Fleck O, Watson AT, Poitelea M, O’Shea C, Chahwan C, Holmberg C, Kragelund BB, Nielsen O, Osborne M, Carr AM, Liu C. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1145–1159. doi: 10.1101/gad.561910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marchetti MA, Weinberger M, Murakami Y, Burhans WC, Huberman JA. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:124–131. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mochida S, Esashi F, Aono N, Tamai K, O’Connell MJ, Yanagida M. EMBO J. 2004;23:418–428. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moser BA, Brondello JM, Baber-Furnari B, Russell P. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4288–4294. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4288-4294.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marguerat S, Schmidt A, Codlin S, Chen W, Aebersold R, Bahler J. Cell. 2012;151:671–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.King MC, Lusk CP, Blobel G. Nature. 2006;442:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature05075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen JS, Beckley JR, McDonald NA, Ren L, Mangione M, Jang SJ, Elmore ZC, Rachfall N, Feoktistova A, Jones CM, Willet AH, Guillen R, Bitton DA, Bahler J, Jensen MA, Rhind N, Gould KL. G3 (Bethesda) 2015;5:361–370. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.015701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deshpande GP, Hayles J, Hoe KL, Kim DU, Park HO, Hartsuiker E. DNA Repair. 2009;8:672–679. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burke B, Stewart CL. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:369–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meister P, Gehlen LR, Varela E, Kalck V, Gasser SM. Methods Enzymol. 20105;470:35–567. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)70021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mizuguchi T, Fudenberg G, Mehta S, Belton JM, Taneja N, Folco HD, FitzGerald P, Dekker J, Mirny L, Barrowman J, Grewal SI. Nature. 2014;516:432–435. doi: 10.1038/nature13833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamazaki S, Hayano M, Masai H. Trends Genet. 2013;29:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayashi MT, Takahashi TS, Nakagawa T, Nakayama J, Masukata H. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:357–362. doi: 10.1038/ncb1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rhind N, Gilbert DM. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:1–26. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heichinger C, Penkett CJ, Bahler J, Nurse P. EMBO J. 2006;25:5171–5179. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Funabiki H, Hagan I, Uzawa S, Yanagida M. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:961–976. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.5.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayano M, Kanoh Y, Matsumoto S, Masai H. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:2380–2391. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01239-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar A, Mazzanti M, Mistrik M, Kosar M, Beznoussenko GV, Mironov AA, Garre M, Parazzoli D, Shivashankar GV, Scita G, Bartek J, Foiani M. Cell. 2014;158:633–646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kobayashi T. BioEssays. 2008;30:267–272. doi: 10.1002/bies.20723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.