Abstract

There are few in vitro models of exocrine pancreas development and primary human pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC). We establish three-dimensional culture conditions to induce the differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) into exocrine progenitor organoids that form ductal and acinar structures in culture and in vivo. Expression of mutant KRAS or TP53 in progenitor organoids induces mutation-specific phenotypes in culture and in vivo. Expression of TP53R175H induced cytosolic SOX9 localization. In patient tumors bearing TP53 mutations, SOX9 was cytoplasmic and associated with mortality. Culture conditions are also defined for clonal generation of tumor organoids from freshly resected PDAC. Tumor organoids maintain the differentiation status, histoarchitecture, phenotypic heterogeneity of the primary tumor, and retain patient-specific physiologic changes including hypoxia, oxygen consumption, epigenetic marks, and differential sensitivity to EZH2 inhibition. Thus, pancreatic progenitor organoids and tumor organoids can be used to model PDAC and for drug screening to identify precision therapy strategies.

Introduction

Patients diagnosed with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic have a five- year survival rate of less than 3.0 percent. Late presentation and high mortality highlight a need for early detection methods and new treatment strategies. More than 95% of pancreatic cancers originate from the exocrine compartment, comprised of acinar and ductal cells1,2. The cellular origins of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) are poorly understood. Dysregulation of KRAS, p16INK4A/CDKN2A, TP53, and SMAD4/DPC4 are frequently associated with PDAC3. Neither the biological changes associated with precancerous lesions (such as pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN)) nor their progressions to PDAC are well understood. Progenitors isolated from the mouse pancreas and grown in organoid cultures have been used to investigate normal ductal morphogenesis and model early disease4–6. However, there is a lack of culture models for understanding mechanisms associated with initiation and progression of human PDAC.

Several studies have shown that human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) can be committed towards the pancreatic endocrine lineage to generate insulin-producing beta-cells7–9. Differentiated PSCs towards exocrine lineage to generate ductal and acinar cells can be used to model normal development in culture. In addition, organoids may be used to understand cancer biology and for developing and validating new therapeutic options. Here we report conditions for inducing exocrine differentiation of PSC-derived pancreatic progenitors and for growing primary human PDAC as tumor organoids in three-dimensional (3D) culture. The tumor organoids can be clonally derived and recreate histoarchitectural heterogeneity observed in matched tumors. Using progenitor organoids, we identify changes in SOX9 localization as a clinically relevant phenotype associated with mutant TP53 expression. In addition, using tumor organoids we identify patient-specific differences in EZH2 dependency and biology.

Results

Induction of polarized organoids from human pluripotent stem cells

Ductal/acinar lineages develop from NKX6.1+PDX1+ progenitors in vivo10. A PSC-derived, pancreatic lineage committed population containing NKX6.1+PDX1+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a) was plated in three-dimensional (3D) culture and screened for growth factors and nutrients critical for pancreas development11,12. A combination of factors including FGF2, insulin, hydrocortisone, ascorbic acid, all trans retinoic acid and B27 serum-free supplement induced polarized 3D structures from 10–20% of PSC-derived cells (Fig. 1a). Those that did not form structures died during the process.

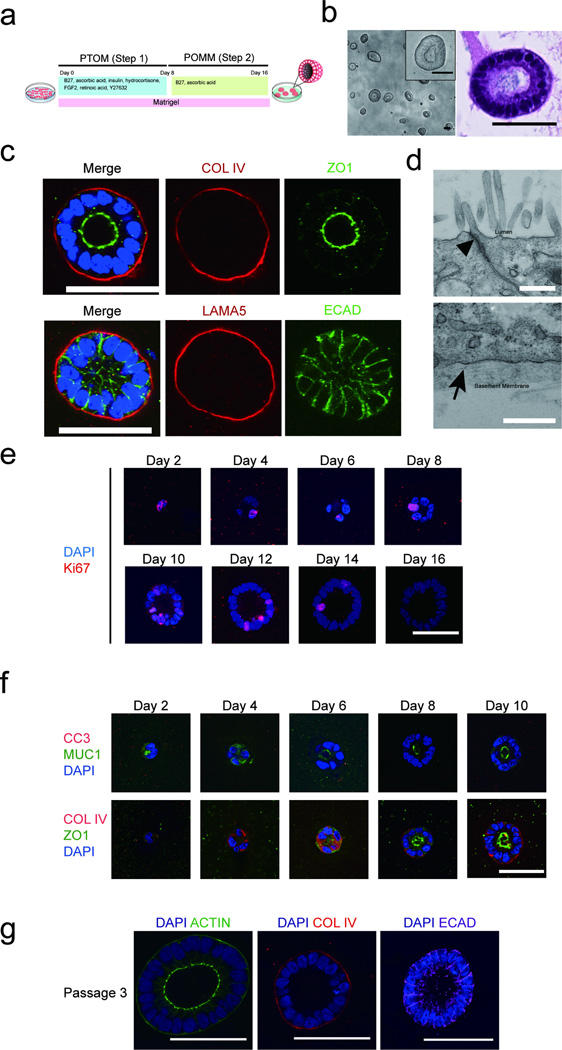

Figure 1. Induction of polarized organoids from human pluripotent stem cells.

(a) A schematic diagram of the protocol for growing pancreatic lineage committed pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) on a 3D platform. PTOM refers to Pancreatic Progenitor and Tumor organoid Media and POMM refers to Pancreatic Organoid Maintenance Media. See online methods for details. (b) Phase morphology of day 16 organoids (left panel) with insert representing higher magnification image of one organoid. H&E staining of one organoid (right panel). (c) Confocal images of day 16 organoids immunostained for basal markers COLLAGEN IV (COLIV) or LAMININ α5 (LAMA5) (red), tight junction marker (ZO1, green), cell-cell junction marker, E-CADHERIN (ECAD, green) and DAPI (blue). (d) Transmission electron micrograph of cells from day 16 3D organoids. Upper panel: apical region of epithelia, arrowhead pointing to an electron dense region representing tight junctions. Lower panel: basal region of polarized epithelia with the arrowhead pointing to basement membrane. Scale bars, 0.5 µm. (e) Staining for Ki67 at different days in 3D culture. DAPI, blue; Ki67, red. (f) Cell polarization and apoptosis during pancreatic organoid morphogenesis. Top panel: apoptosis marker Cleaved Capase-3 (CC3, red), and apical maker MUCIN1 (MUC1, green), DAPI (blue). Bottom panel: basal and apical markers COLIV (red) and ZO1 (green), respectively in progenitor organoids from day 2 to day 10 in 3D culture. (g) Maintenance of polarity upon serial passaging of organoids as shown by staining for ACTIN (green), COL IV (red) and ECAD (purple). Scale bars represent 50 µm, unless specified otherwise.

Structures were mostly clonally derived (Supplementary Fig. 1b) and comprised of one layer of polarized epithelia surrounding a hollow central lumen (Figure 1b, 1c). Cells also secreted basement membrane as assessed using human Collagen IV and Laminin α5-specific antibodies (Fig. 1c). Tight junctions, basement membrane and apical microvilli were detected by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 1d). Karyotyping confirmed that these cells had normal diploid genomes (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Cell proliferation and control of organ size are important for normal tissue morphogenesis. The progenitor organoids underwent significant increases in size and were highly proliferative from days 0 to 12, (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 1d and 1e). By day 14, >95% of organoids were proliferation arrested with a diameter ranging between 30–200 µm (Supplementary Fig. 1d and 1e).

Consistent with the finding that apoptosis is not required during lumen formation in embryonic pancreatic ducts in vivo13, we rarely detected cleaved caspase 3 in the organoids (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 1f). Apical-basal polarity was established starting at day 8, as monitored using MUC1, and ZO-1 (apical marker) and Collagen IV (basal marker) staining (Fig. 1f). Day 16 organoids can be serially passaged (tested to passage 5) to re-initiate organogenesis (Supplementary Fig. 1g). These organoids maintained size control, had hollow lumens and apical-basal polarity (Fig. 1g).

Organoids express markers associated with pancreatic progenitor cells

Global gene expression analysis and unsupervised clustering placed 3D organoids close to human pancreas compared to endodermal cells or a human mammary epithelial cell line (MCF-10A) (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Expression of pancreas specific markers (NKX6.1, PTF1A) was significantly higher in 3D organoids compared to endoderm-derived organs (Fig. 2a). By contrast, expression of liver (albumin, CREBPA), stomach (SOX2) and duodenum (CDX2) markers were significantly lower in both human pancreas tissue and 3D organoids compared to respective organs (Fig. 2b).

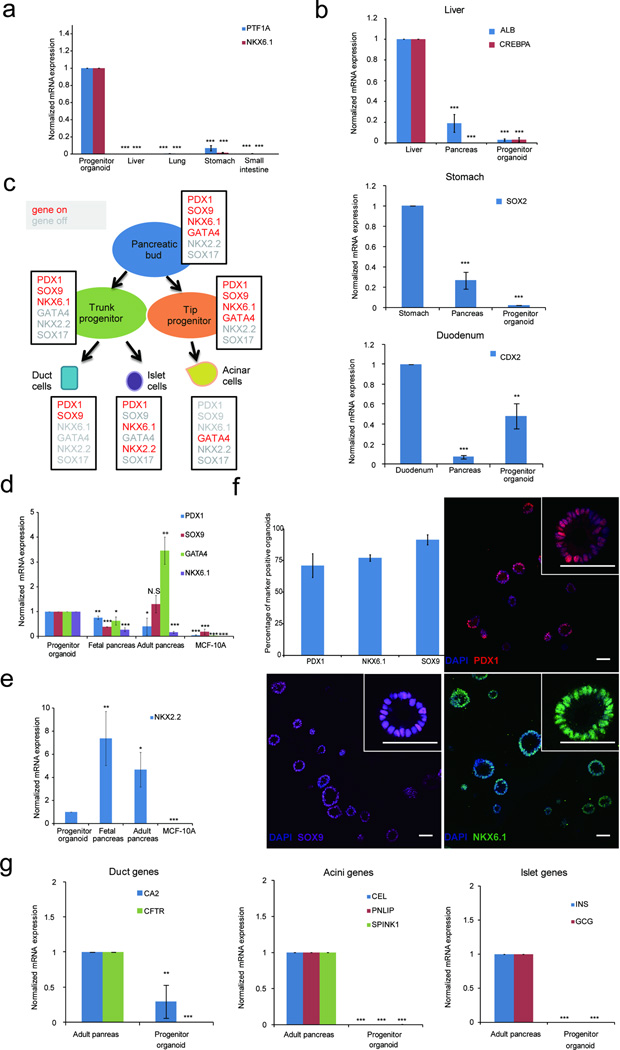

Figure 2. Organoids express markers associated with pancreatic progenitor cells.

(a) Expression of pancreas exocrine specific marker genes in 3D organoids and human fetal endodermal tissues. (b) Expression of markers for liver (ALB, CREBPA), stomach (SOX2) and duodenum (CDX2) in 3D organoids, human fetal pancreas and positive control (fetal liver or fetal stomach or fetal duodenum). (c) A schematic summarizing expression patterns of transcription factors during human embryonic pancreas development. Expressed genes are in red; repressed genes are in grey, adapted from Jennings et al10. (d) Expression of pancreas markers in 3D organoids, MCF-10A mammary epithelial cells used as non-specific control. (e) Expression of NKX2.2, a pancreatic endocrine marker gene. (f) Expression of markers in 3D organoids as detected by immunofluorescence. Images show representative fields and inserts show one organoid at a higher magnification. Scale bars, 50 µm. Graph summarizes results from three independent sets of experiments with over 100 organoids counted for each experiment. An organoid was designated as marker positive when more than 50% cells were positive for expression. (g) Expression of markers associated with differentiated ductal, acinar or islet cells. CA2, carbonic anhydrase II; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; CEL, carboxyl ester lipase; PNLIP, pancreatic lipase; SPINK1, serine peptidase inhibitor 1; INS, insulin; GCG, glucagon. For all qPCR experiments data represent mean +/− S.E.M. P value (t-test, two tailed): N.S. - not significant; *P = 0.01 – 0.05; **P= 0.001 – 0.01; ***P = < 0.001 (N = 3 biological repeats).

We monitored expression of transcription factors that are expressed in a cell type-specific manner within the pancreas (Fig. 2c)10,14,15. Organoids expressed higher levels of progenitor (PDX1, NKX6.1) and lower levels of islet (NKX2.2) cell markers compared to fetal and adult pancreas, and lower levels of an acinar marker (GATA4) as compared to adult pancreas (Fig. 2d, 2e). We next analyzed expression of these markers by immunofluorescence. PDX1, SOX9 and NKX6.1 proteins were expressed in the majority of organoids (Fig. 2f). PDX1 protein expression was heterogeneous within each organoid (Fig. 2f). All cells within organoids expressed pancreatic epithelia associated Cytokeratin 19 (KRT19) (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Our conditions promoted exocrine lineage specification as determined by a 3.5-fold increase in SOX9 expression beginning on day 6 and suppressed endocrine lineage commitment, as assessed by low NGN3 expression (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Expression of pancreatic progenitor markers (PDX1, PTF1A) remained constant from day two until day 16. Next we examined if the organoids express markers associated with differentiated acinar, ductal or islet cells. Expression of ductal (CA2,CFTR), acinar (CEL, PNLIP, SPINK) and islet (insulin and glucagon) cell markers were either undetectable or lower (CA2) in organoids as compared to adult pancreas (Fig. 2g), suggesting that these structures were not terminally differentiated and consisted largely of progenitor cells. Henceforth, we refer to these structures as progenitor organoids.

Differentiation of pancreatic progenitor organoids in vitro and in vivo

Since Wnt, Notch, TGFβ and Hedgehog pathways have been implicated in normal pancreas development11,12, we modified our protocol (Fig. 1a) to induce differentiation of progenitor organoids by modulating these pathways. Step 2 involved TGFβRI (A8301) and Notch (DBZ) inhibition (PODM I) and step 3 included growth factors as indicated (Fig. 3a). This protocol induced differentiation of progenitor organoids to a population containing both 10–15% CA2+ ductal and 0.5–1% CPA1+ acinar organoids, as monitored by increases in mRNA expression of acinar and ductal markers (Fig. 3b).

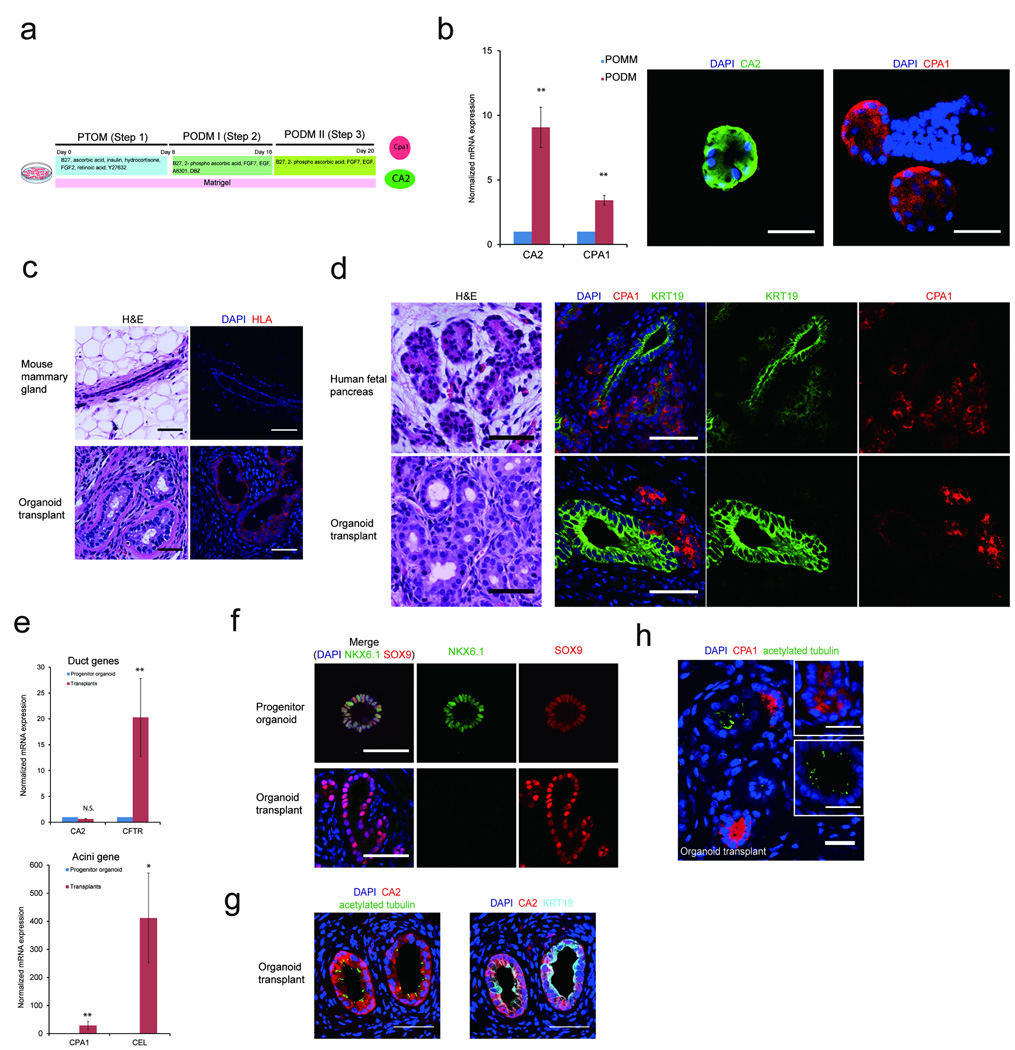

Figure 3. Differentiation of pancreatic progenitor organoids in vitro and in vivo.

(a) Schematic representation of the protocol for inducing progenitor organoids into ductal and acinar cells in culture. PTOM refers to Pancreatic Progenitor and Tumor organoid Media; PODM I and PODM II refer to Pancreatic Organoid Differentiation Media I and II. (b) QPCR analysis for ductal (CA2) and acinar (CPA1) markers. Immunofluorescence analysis of CA2 (green) and CPA1 (red) expression. (c) Top panel: H&E morphology of mammary ducts of control glands (left) and immunofluoresence for human leukocyte antigen (HLA), (right, HLA-Red). Bottom panel: organoid transplants stained with H&E (left) or for HLA (right). Transplants were identified in 20 out of 22 glands analyzed. (d) Comparative analysis of organization of H&E stained human fetal pancreas (top) with transplants (bottom) and immunofluorescence using ductal (KRT19, green), and acinar (CPA1, red) markers. (e) QPCR analysis showing expression of acinar (CPA1, CEL) and ductal (CA2, CFTR) markers relative to the progenitor organoids in transplants. (f) NKX6.1 expression in, progenitor organoids in culture (top) and ducts in transplants (bottom). DAPI, blue; NKX6.1, green; SOX9, red. (g) Transplants immunostained for ductal markers CA2 (red), KRT19 (cyan), primary cilia (acetylated tubulin, green) and DAPI (blue). (h) Transplants immunostained for ductal marker, primary cilia (acetylated tubulin, green) and acinar marker (CPA1, red) and DAPI (blue). All scale bars represent 50 µm. P = 0.01 – 0.05; **P= 0.001 – 0.01; ***P = < 0.001 (N = 3 biological repeats).

We also tested if the mouse mammary gland fat pad, which is known to support growth of pancreatic islets16, would induce differentiation of progenitor organoids into pancreatic exocrine structures. Dissociated day 16 organoids were injected into 6–8 wk old female NOD/SCID mice. Fifteen weeks after injection more than 90% of the glands had Human Leukocyte Antigen I (HLA I)-positive human cell outgrowths, that were morphologically distinct from endogenous mammary ductal structures (Fig. 3c). Transplants had anatomic organization as human fetal pancreas tissue sections10,17, with CPA1+ acinar cell clusters located near KRT19+ ductal structures (Fig. 3d), demonstrating that progenitor organoids can undergo organogenesis in vivo.

Human acinar (CPA1, CEL) and ductal (CFTR) marker expression was increased in organoid transplants relative to progenitor organoids, while CA2 expression was unaffected (Fig. 3e). Organoid transplants lacked NKX6.1 but maintained SOX9 expression in vivo as expected10 (Fig. 3f). Differentiated pancreatic ducts or islets, but not acini, are known to have primary cilia18. In organoid transplants, primary cilia were observed in CA2+ ductal but not in CPA1+ acinar-like structures (Fig. 3g and 3h). Thus, progenitor organoids can generate outgrowths with molecular and morphological characteristics of human fetal exocrine pancreas.

Pancreatic cancer modeling using progenitor organoids

Progenitor organoids may model phenotypes associated with mutations in KRAS and TP53, two of the most frequently observed alterations in PDAC19,20. Pancreatic lineage committed cells were infected with mCherry (control), KRASG12V or TP53R175H, a dominant negative mutant of TP53. KRASG12V- and TP53R175H-transduced organoids expressed detectable levels of the transgene (Supplementary Fig. 3a and 3b) and were larger with more cells per structure than mCherry-transduced organoids (Fig. 4a, 4b). Unlike KRASG12V organoids, low proliferation rates were detectable in TP53R175H organoids by day 16 (Fig. 4b, 4c).

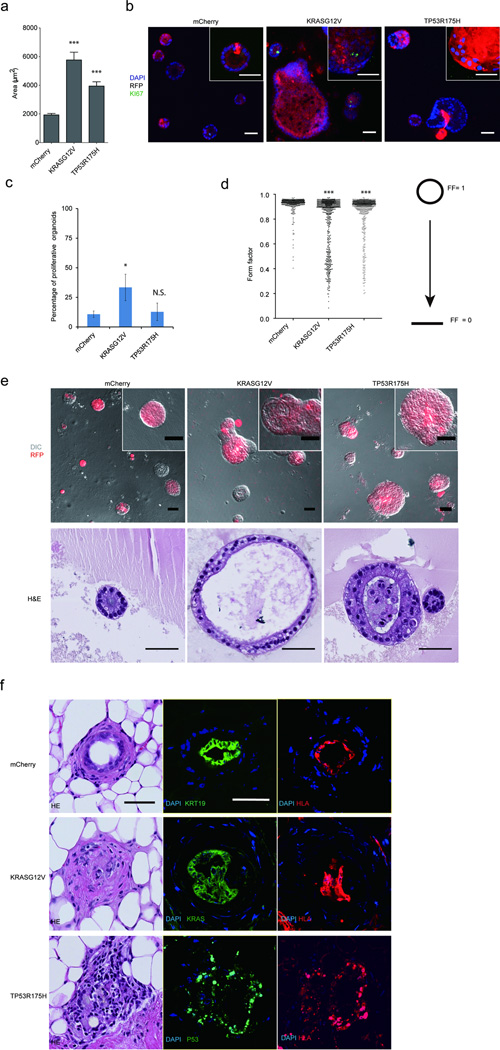

Figure 4. Progenitors organoids model early PDAC.

(a) Areas of progenitor organoids expressing transgenes. (b) Representative images of mCherry, TP53R175H and KRASG12V expressing structures stained for Ki67 (green), RFP (red) and DAPI (blue). (c) Quantification of the percentage of proliferative organoids. (d) Form factor (FF) analysis, a continuous scale where a perfect circle is represented by FF=1 and a linear line by FF=0. (e) Overlay of DIC and fluorescent images of KRASG12V and TP53R175H expressing structures (top) and sections stained with H&E (bottom panel). All quantification graphs summarize three independent experiments with N >100 structures assessed in all cases, N.S-, not significant; * P = 0.01 – 0.05; ** P = 0.001 – 0.01; ***P = < 0.001 (N = 3 biological repeats). (f) Transplant outgrowths from progenitor organoids expressing mCherry, KRASG12V or TP53R175H. Morphologies of organoid-derived structures are shown by H&E images. Expression of Keratin19 (KRT19, green), KRAS (green) or TP53 (green), DAPI (blue) as well as human marker HLA (red) are shown in immunofluorescent images. All scale bars represent 50 µm.

Both KRASG12V and TP53R175H organoids were also disorganized compared to mCherry, as determined by form factor analysis (Fig. 4d). KRASG12V-expressing organoids showed cystic organization with apically positioned nuclei and morphology consistent with early pancreatic tumor lesions (Fig. 4e), whereas, TP53R175H-expressing organoids had atypical organization with apically positioned nuclei and filled lumens (Fig. 4e).

After 16 days in culture, organoids were injected into 8–10 mammary fatpads of NOD/SCID mice. 22 weeks later, we confirmed the structures that grew were of human origin by HLA and transgene staining (Fig. 4f). mCherry-transduced organoid-derived outgrowths showed normal ductal organization, whereas KRASG12V- or TP53R175H-expressing outgrowths showed abnormal ductal architecture and nuclear morphology consistent with neoplastic transformation (For details see Supplementary Fig. 3c and 3d). Thus, both in culture and in vivo, progenitor organoids can serve as models for investigating early stages of transformation.

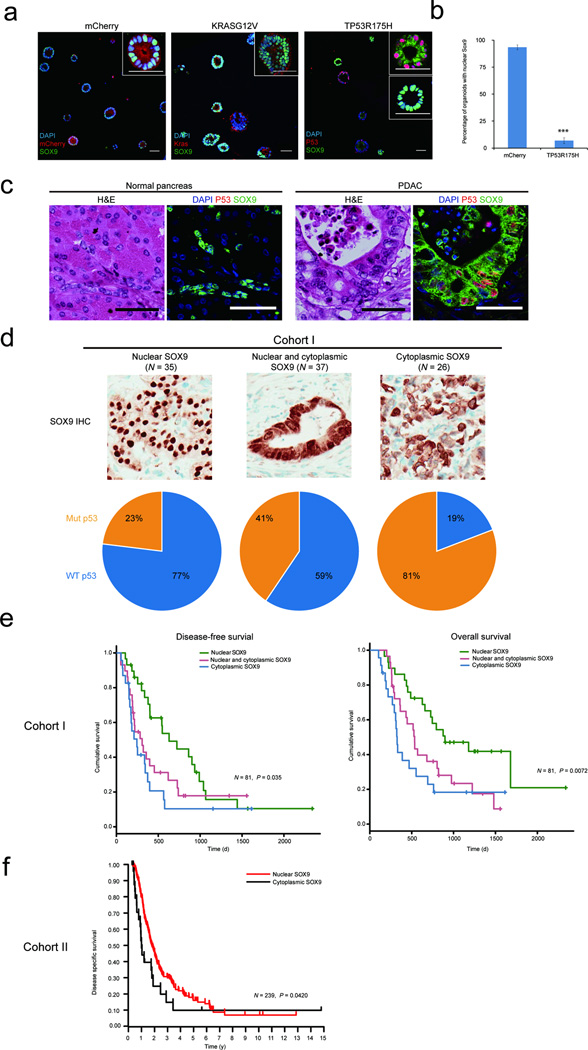

Cytoplasmic SOX9, TP53 status and clinical outcome

Next, we investigated changes in the expression of differentiation markers in KRASG12V and TP53R175H organoids. Among the markers analyzed, SOX9 was localized in the cytoplasm in TP53R175H, but not in mCherry or KRASG12V organoids (Fig. 5a, 5b). In breast cancer, cytoplasmic SOX9 is a marker of poor prognosis21,22. Therefore we investigated SOX9 localization in normal human pancreas and PDAC. In normal pancreas samples (N = 4) SOX9 was localized in the nucleus, whereas in TP53-mutated PDAC SOX9 was localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5c). To understand the clinical relevance of this observation, we analyzed two independent cohorts of PDAC samples (cohort I: N = 98; cohort II: N= 242) for SOX9 localization and TP53 status. Among the PDAC samples with nuclear SOX9 77% had wild-type TP53 whereas 81% of samples with cytoplasmic SOX9 had mutant TP53; this association between TP53 status and SOX9 localization was significant (P = 3.25×10−5) (Fig. 5d). In addition, in cohort I, increased cytoplasmic SOX9 was significantly associated with poor disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) (DFS: P = 0.035, OS: P = 0.0072) (Fig. 5e). In cohort II, cytoplasmic SOX9 was associated with higher tumor grade (P = 0.0485) and worse disease-specific survival compared to patients with nuclear SOX9 (P = 0.0420) (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 5. TP53 mutational status, localization of SOX9 and clinical outcome.

(a) Control vector (mCherry), or KRASG12D or TP53R175H expressing organoids co-stained for SOX9 (green) and KRAS or TP53 (red), DAPI, blue. Insets represent high-resolution images of representative organoids. (b) Quantification of nuclear SOX9 in mCherry- and TP53R175H-expressing pancreatic progenitor organoids. Graph summarizes results from three independent sets of experiments with over 50 structures counted in each experiment. ***P =< 0.001. (c) H&E and immunostaining for TP53 (P53, red) SOX9 (green) in normal pancreas and PDAC. Scale bars, 50 µm. (d) Representative images of chromogenic IHC staining showing nuclear, nuclear-cytoplasmic and cytoplasmic SOX9 staining (top panel). Samples with different SOX9 status scored for TP53 mutation status and expressed as percentage (lower panel). WT refers to Wild type. (e) Kaplan-Meier curve representing disease free survival (DFS) an overall survival (OS) of patients in cohort I with nuclear (green, N = 29), nuclear and cytoplasmic (red, N = 29), or cytoplasmic SOX9 (blue, N = 23). (f) Kaplan-Meier curve representing disease specific survival of patients in cohort II with cytoplasmic (black, N = 26) or nuclear SOX9 (red, N = 213).

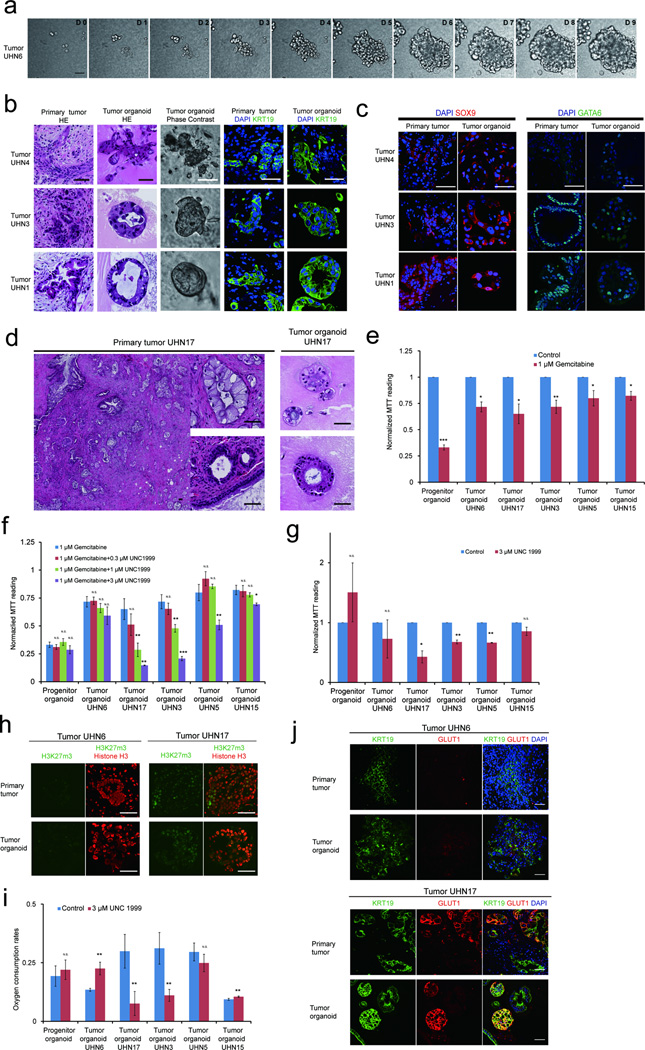

Tumor organoids conserve histology and phenotypic heterogeneity

As PDAC originates from the exocrine lineage, we reasoned that our culture conditions may be adapted for growing primary pancreatic tumors. Twenty primary tumor samples obtained from surgical resections under institutionally approved research ethics protocols were used to establish organoid cultures and patient consents were obtained. Tumor organoids were established for 17/20 samples; the 17 that grew were PDAC and the three that failed were intraductal papillary mucinous cystic neoplasm, poorly to moderately differentiated PDACs (Supplementary Table 2).

Image analysis of University Health Network pancreatic cancer patient 17 (UHN17)-derived organoid culture (Supplementary Fig. 4a) demonstrated that organoids were often clonally derived. Time-lapse analysis of UHN6 culture every 45 minutes for 10 days (Fig. 6a) revealed that organoids show dynamic behavior, with structures moving and merging with others, and cells dispersing from an organoid (Supplementary Movie 1). We analyzed the histoarchitecture and differentiation status of the tumor organoids after 16 days. Tumor organoids retained similar morphological and cytological features as the primary tumors they were derived from (Fig. 6b), with similar expression of differentiation markers including KRT19, GATA6, and SOX9 (Fig. 6b and 6c). None of the tumors or organoids expressed islet (NKX6.1) or acinar (GATA4) cell markers (Supplementary Fig. 4b).

Figure 6. Establishment of tumor organoids that conserve patient specific traits.

(a) Time lapse imaging sequence of UHN6 organoids. (b) H&E, phase and immunofluorescence images for KRT19 (green) and DAPI (blue) of images of tumor organoids and their matched primary tumors. (c) SOX9 (red) and GATA6 (green) staining in primary tumors and tumor organoids. (d) H&E images of primary patient tumor and matched tumor organoids. (e) MTT assay readings of organoid cultures treated with gemcitabine for 4 days. Results were normalized to vehicle-treated organoids. (f) MTT assay readings of organoid cultures with gemcitabine and epigenetic inhibitor of the H3K27me3 writer EZH2 (UNC1999). Results were normalized to vehicle-treated organoids. (g) MTT reading of tumor organoids treated with UNC199 alone. Results were normalized to vehicle-treated organoids. See online methods for details. (h) Immunostaining for H3K27me3 (green) and histone H3 (red) in two primary patient tumors (top panel) and corresponding tumor organoids (bottom panel). (i) Basal O2 consumption rate as measured by Seahorse™ flux analyzer with and without UNC1999 treatment. (j) GLUT1 (red) expression in primary tumors and tumor organoids derived from tumor UHN6 and UHN17. KRT19 (green) and DAPI (blue). For MTT and oxygen consumptions experiments, data represent mean +/− S.D. P value (t-test, two tailed): N.S-, not significant; *P= 0.01 – 0.05; **P= 0.001 – 0.01; ***P= < 0.001 (N= 3 technical repeats). All scale bars equal to 50 µm.

To determine whether tumor organoids can be serially passaged and form tumors in vivo, we analyzed organoid forming efficiencies and growth rates from three PDAC patients. All samples effectively established serial cultures and maintained similar growth rates during assay periods (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Cells formed organoids better at higher densities than at lower densities (5–10%) and the low organoid forming efficiency of UHN17 in passage three was an indirect consequence of individual organoids moving and merging to form large structures (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Tumor organoids can be freeze-thawed to re-establish cultures maintaining phase and hematoxyln and eosin stain (H&E) morphology across passages (Supplementary Fig. 4d). To test whether the tumor organoids can generate tumors in xenograft models, we subcutaneously injected 50,000 cells from two independent organoid cultures (Supplementary Fig. 4e and data not shown) into NSG mice (N= 6 sites per organoid). All injections resulted in tumor growth within 4–7 weeks. The xenograft tumors maintained the histoarchitectures present in the primary tumors from which the organoids were derived and can be used to re-establish organoid cultures (Supplementary Fig. 4e).

Carcinomas display intratumoral spatial histological heterogeneity23, which was maintained in our tumor organoid system. For example, a primary PDAC showing two distinct populations of invasive glands, composed of larger tall columnar cells with cleared granular cytoplasm or smaller cuboidal cells with deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm, generated organoids recapitulating these morphologically distinct populations (Fig. 6d). Thus, we demonstrate that tumor organoids conserve histological organization, differentiation status and morphologic heterogeneity observed in primary PDACs, a property we refer to as histostasis.

Tumor organoids as platforms for personalized drug testing

Despite the availability of multiple drug regimens for treating PDAC, the five year survival rate for patients with PDAC is only six percent2. Large-scale genomics studies demonstrate patient-specific variations in genetic and epigenetic changes, highlighting the need to use fresh patient tumor material to evaluate or discover new therapies that can be administered on a personalized basis24.

We analyzed five independent patient tumor derived organoids--UHN6, UHN17, UHN3, UHN5 and UHN15. All cultures show poor response to gemcitabine, the current standard of care, with 30% growth inhibition (Fig. 6e). As all patients underwent surgery within the past five months and are currently alive without evidence of disease, we cannot relate organoid response to gemcitabine with patient outcome.

We next tested the five tumor organoid models against drugs targeting epigenetic regulators. These agents were selected due to the lack of treatments targeting mutations frequently observed in PDAC (KRAS, TP53, CDNK2A, and SMAD4). Among the inhibitors tested using progenitor organoids (Supplementary Table 3) inhibitors of G9a (A366) and EZH2 (UNC1999), writers for H3K9me2 and H3K27me3 repressive marks respectively, were least toxic (data not shown) and selected for further study. Tumor organoids were treated with A366 and UNC1999 alone or in combination with gemcitabine. While tumor organoids were insensitive to A366 (Supplementary Fig. 5a), UHN17, UHN3, UHN5, and UHN15 but not UHN6 tumor organoids, demonstrated a dose-dependent decrease in proliferation upon addition of UNC1999 as compared to gemcitabine treatment alone (Fig. 6f). UNC1999 alone also suppressed proliferation of UHN17, UHN3, UHN5 but not UHN6 and UHN15, suggesting EZH2 dependency in the former group (Fig. 6g). As expected, the matched tumor and organoids of UHN17, UHN3, UHN5 but not UHN6 and UHN15, were positive for the H3K27me3 mark (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Fig. 5c). UNC1999 suppressed H3K27me3 in UHN17 organoids at concentrations showing significant growth-inhibitory effects (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Recent studies reveal a relationship between oxygenation and H3K27me3 epigenetic mark regulation25,26. Furthermore, cells contributing to PDAC tumor relapse show increased oxidative phosphorylation dependence27. We measured basal respiration rates to investigate differences in tumor organoid oxygen consumption. UHN17, UHN3 and UHN5 showed 2–3 fold higher normalized basal oxygen consumption rates as compared to UHN6 and UHN15 organoids (Fig. 6i). Increased oxygen consumption was suppressed by UNC1999 in UHN17 and UHN3, suggesting a relationship between epigenetic status and oxygen consumption. UHN6 and UHN15 organoids and matched tumors also differed in expression of the hypoxia marker, GLUT1 (Fig. 6j). Thus tumor organoids retain patient-specific traits including repressive epigenetic marks, oxygen consumption and EZH2 dependence, highlighting the utility of this system for drug screening.

Discussion

We report conditions for inducing human PSC differentiation to pancreatic exocrine lineage organoids and use these organoids to obtain clinically relevant insights to PDAC. We also adapt the approach for establishing and propagating primary PDAC tumors as organoids that maintain tumor-specific traits and show differential responses to novel therapeutic drugs.

Previous reports have used mouse pancreas tissue progenitors to develop organoid cultures of ductal cells, which can be manipulated and transplanted in-vivo4–6,28. We report conditions for differentiation of human PSCs towards exocrine lineage in culture and in vivo. Among the pathways associated with pancreas development, we found TGFβ and Notch inhibition facilitated differentiation into ducts and acini, while Hedgehog inhibition and Wnt activation at stage II and III of induction redirected the developmental program away from the pancreatic lineage (data not shown). Further studies using this model will facilitate a better understanding of human pancreatic exocrine differentiation, which has implications for regenerative medicine.

Progenitor organoids can identify genotype-phenotype relationships in PDAC. For example, TP53R175H, but not KRASG12V, induces cytosolic SOX9 localization. Using two cohorts of human PDAC samples, we validate the correlation between cytosolic SOX9 and mutant TP53 status. Although the mechanistic relationship between TP53 and SOX9 localization remains unknown, it highlights the utility of progenitor organoids. Although this model can provide insights into early lesions, our KRASG12V-induced lesions do not contain luminal space, precluding an evaluation of changes in nuclei position associated with PanINs. To the best of our knowledge, the effects of TP53 mutations in wild type KRAS PanINs are not known, hence the significance of our TP53R175H histopathology for human PanINs warrants further investigation.

We also report conditions that support tumor organoid growth from surgical resections of PDAC with high efficiency (>80%). A recent study reported a method to establish tumor organoids that have histological features consistent with low-grade PanINs, despite being derived from adenocarcinoma28. In contrast, our conditions promote histostasis where the organoids conserve inter-patient variation in tumor histoarchitecture, and maintain the differentiation status observed in the matched primary tumor.

PDAC organoids have been used for Omics approaches to compare mouse and human tumors to gain insights28. We demonstrate the use of clonally-derived organoids to identify patient-specific sensitivities to novel therapeutic agents. Organoids from different patients showed differential sensitivity to EZH2 inhibition, which correlated with H3K27me3 in both tumor organoids and matched patient tumor. The relatively short time required to establish organoid cultures from the time of surgery (21–45 days) minimizes culture-induced genetic drift and is hence likely to better represent the primary tumor than established cell-lines. This suggests organoids may be used to predict clinical response and for personalized cancer treatment.

Online Methods

Three dimensional culture of organoids

Human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived pancreatic progenitors were generated in a monolayer format using a modification of our previously described staged differentiation protocol30,31. Stem cells were regularly tested to be mycoplasma free using MycoAlert (Lonza). To generate definitive endoderm, hESCs (MEL1 cell line, provided by Drs. E. Stanley and A. Elefanty) on MEFs were induced with 100 ng/ml ActivinA (R&D Systems) and 1 µM CHIR 99021 for 1 day in RPMI supplemented with 2 mM glutamine (Gibco-BRL) and 4.5 × 10−4 M MTG (Sigma), then with 100 ng/ml ActivinA and 1 µM CHIR 99021 and 2.5 ng/ml bFGF (R&D Systems) for 1 day in RPMI supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 0.5 mM ascorbic acid (Sigma), and 4.5 × 10−4 M MTG. The media was then changed to 100 ng/ml ActivinA and 2.5 ng/ml bFGF for an additional day in RPMI supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, and 4.5 × 10−4 M MTG. The day three endoderm population was next patterned for two days by culture in the presence of 250 nM KAAD-cyclopamine (Toronto Research Chemicals, ON, Canada) in RPMI supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 4.5 × 10−4 M MTG and 1% vol/vol B27 supplement (Invitrogen). At this stage, pancreatic progenitors were induced with 50 ng/ml noggin, 250 nM cyclopamine, 2 µM retinoic acid, and 50 ng/ml exendin4 for two days in DMEM supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 0.5 mM ascorbic acid and 1% B27. Following induction, the population was cultured in the presence of 50 ng/ml noggin, 50 ng/ml EGF, 1.2 ug/ml Nicotinamide, and 50 ng/ml exendin4 DMEM supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 0.5 mM ascorbic acid and 1 % B27 to promote the development of PDX-1+NKX6.1+ progenitors31). Cells were harvested at day nine of differentiation for generation of ductal/acinar structures.

For pancreas progenitor organoid culture, T9 cells were resuspended and plated in the PTOM (Pancreatic Progenitor and Tumor Organoid Media) containing DMEM with 1% B27, 50 ug/ml ascorbic acid, 20 µg/ml insulin, 0.25 µg/ml hydrocortisone, 100 ng/ml FGF2, 100 nM all-trans retinoic acid and 10 µM Y267632. The cells were plated on a bed of Matrigel as described before29. At day eight in 3D culture, replace culture medium with fresh POMM (Pancreatic Organoid Maintenance Media) (PTOM media contains 1 % B27 and 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid) with 5 % Matrigel every 4 days. PODM I (Pancreatic Organoid Differentiation Media) contains DMEM with 1 % B27, 300 µM 2-phospho ascorbic acid, 100 ng/ml FGF7, 10 ng/ml EGF, 1 µM A8301 and 1 µM DBZ. PODM II contains DMEM with 1 % B27, 300 µM 2-phospho ascorbic acid, 100 ng/ml FGF7, 10 ng/ml EGF. Fresh tissues of primary tumors from patients were washed twice with DMEM, digested with collagenase (Roche) and resuspended in PTOM. Tumor cells were then seeded in 3D culture chambers as described above. Culture media were replaced every 4 days. For serial passaging of organoids, day 16 organoids were treated with collagenase for 2 hours then further dissociated with trypsin for 10–30 minutes. Cells were collected and re-seeded in 3D culture following protocols as described above. MCF-10A cells were obtained from ATCC.

For gene transduction, KRASG12V, TP53R175H and turboRFP were cloned into a pSicoR vector with EF1apha promoter (Addgene, 31847) using Gateway system (Life Technologies). Lentiviruses were packaged using a third generation packaging system and pseudotyped with RabbiesG (Addgene, 15785) in 293T cells. Concentrated virus was used to infect pluripotent progenitors grown on a thin layer of Matrigel in PTOM and subsequently replated in 3D, as outlined above.

Drug treatment

Progenitor cells and primary tumor cells were seeded in 3D as described above and epigenetic inhibitors or DMSO were added to 3D culture at day 1. At day 4 of 3D culture, fresh media with DMSO, epigenetic inhibitors or epigenetic inhibitors/gemcitabine were used to replace media in 3D culture. At day 8, cell growth was analyzed using CellTiter 96 non-radioactive cell proliferation assay (Promega, G4000). Basal oxygen consumption rates of organoids, were measured using a XFe 96 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Biosciences). In brief, 2500 cells were seeded to each matrigel coated well of an XFe 96 cell culture plate. At day 8, basal oxygen consumption rates were measured and values normalized to fluorescence intensity readings, obtained from CyQUANT (Thermo-Scientific) cell proliferation assays conducted on the XFe 96 cell culture plate.

Transmission electron microscopy

Day 16 3D structures were washed once with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by fixation with 2% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM Na-Cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and processed at the Cell and Systems Biology Imaging Facility of University of Toronto. Sections of 1µm thickness were stained with Toludine/Methylene blue and the region of interest were examined with a Hitachi H7000 TEM.

Immunofluorescence and IHC

At the time points of interests, 3D cultured cells in chamber slides were fixed with 4% PFA and processed as in 3D culture of MCF-10A cells29. Tissues and histogel blocks were fixed in 10% Formalin and paraffin blocks were processed using standard immununohistochemistry protocol. Tumor organoids and patient primary tumors were compared by two clinical pathologists blindly. Patient tissue microarrays were analyzed by two clinical pathology groups. Patients who underwent curative surgical resection of histologically confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma who provided consent to tissue and molecular research were included in the study. Patients were excluded if they had been lost to follow-up or died within 90 days of their surgical resection. Staging, clinical, surgical pathologic and treatment data were retrospectively extracted from a prospectively maintained database. Univariate and multivariate comparisons of disease-free and overall survival were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method by Log-rank and Cox-proportional Hazards models, respectively.

Alexa fluorophore labeled secondary antibodies for corresponding primary antibodies were purchased from Life Technologies and used at 1:400. Primary antibody dilutions and catalog numbers: PDX1, 1:100, (Cell Signaling #5679); Amylase, 1:100, (Cell Signaling #3796); Cleaved Caspase-3, 1:100, (Cell Signaling #9579); CPA1, 1:100, (AbD Serotec #1810-0006); CK19, 1:400, (Abcam #ab9221); Ecadherin, 1:200, (Cell Signaling #3195); GATA4, 1:100, (BD Biosciences #560327; HLA I ABC, 1:100 (Abcam #ab70328); Insulin, 1:100, (Cell Signaling #3014); Ki67, 1:50, (Zymed #18-0191); Lamin α5, 1:100, (Abcam #ab77175); Mucin1, 1:400, (BD Biosciences, #555925); Nkx6.1, 1:100, (DSHB #F55A10); p53, 1:100, (Santa Cruz #sc-126); Sox9, 1:400, (Millipore #5535); ZO-1, 1:200, (Invitrogen #61-7300); CA2, 1:100, (Santa Cruz #sc-25596); GLUT1, 1:200, (Abcam, #ab652).

Image acquisition and analysis

Phase contrast images were acquired on a Nikon TE300 microscope with 4× or 10× objective and a DS-FI2 camera. Confocal images were acquired with the Olympus FluoView 1000 system. Images were acquired with a 20× air objective or a 40× oil objective with 1024×1024 resolution. For all experiments, three independent experiments were conducts with over 50 structures evaluated in each experiment to ensure well representation as we regularly performed in our lab.

For tumor organoid clonality and dynamicity studies, confocal images of organoids were captured using the Nikon C2+si system. For clonality studies, serial imaging was performed every day using a 10× air objective at 2048*2048 resolution. For dynamicity studies, time-lapse imaging was conducted using a 20× air objective, every 45 minutes for 10 days at 2048*2048 resolution. Time-series images were processed to concatenate and align time-series stacks using ImageJ.

For measurement of organoids, phase images were first converted to 8-bit grey scale images then smoothened by ‘smooth keeping edges’ function. Edges of organoids in images were further enhanced by Sobel method and dark holes were suppressed. Organoids were then identified automatically using the ‘identify primary objects’function and threshold was set globally through Ostu method. Object separation was performed by ’Shape’ method, then areas of individual organoids were measured and exported to excel files.

Ki67 staining analysis was done using CellProfiler. Cell nuclei (DAPI) channels and Ki67 channels were separated and loaded into CellProfiler as matched channels. Nuclei and Ki67 within each organoid were registered as primary objects then related by ‘RelateObjects’ function. Then the total cell nuclei area and Ki67 staining area were calculated for each organoid and exported to a spreadsheet. If the ratio of Areaki67/Areanuclei of one organoid was over 0.05 then this organoid was regarded as proliferative. Form factors were calculated as 4*π*Area/Perimeter2. Equals 1 for a perfectly circular object.

Gene expression analysis

Adult pancreas RNAs were purchased from Clontech (636577). Fetal tissue RNAs were purchased from Biochain (www.Biochain.com). RNAs of 3D cultured organoids or cells lines were obtained using Trizol extraction following a previously published method29. For RNA extraction from paraffin slides, RecoverAll Total Nuclei Acid Isolation Kit for FFPE (Life Technologies, AM1975) was used.

Global gene expression analysis was performed using Illumina Human HT-12 v4 Expression BeadChip array. Array hybridization was done following a standard Illumina expression array protocol starting with high quality total RNA from each of the samples. RNA was quantified using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer before processing to prepare for array hybridization. In brief, hybridization protocol features first and second-strand reverse transcription steps, followed by in vitro transcription amplification that incorporates biotin-labelled nucleotides, array hybridization, washing, blocking, streptavidin-Cy3 staining and scanning using iScan. The images were read by Illumina’s GenomeStudio software and probe summary profiles for each sample and intensities of control probes were exported. We then performed background correction and quantile normalization of the intensity data using ‘limma’, an R package (Ref: http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html). All the probes with a detection P value less than 0.01 were excluded from further analysis. If a gene was represented by more than one probe, mean expression values of all those probes were used to represent the expression level of that gene. Hierarchical clustering of expression levels of all 15240 genes based on Euclidean distance.

cDNAs were synthesized using Superscript III First Strand Synthesis Supermix for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). Real-time qPCR analyses were performed with Power SYBR PCR Master Mix on ABI 7900HTsystem. Three technical replicates of three biological replicates were used as empirically done. Student’s t-tests were performed to determine the statistical significances of gene expression differences between different conditions. The primers for PCR are listed as following:

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| ACTIN | GAGCCTCGCCTTTGCCGATCC | CATCCATGGTGAGCTGGCGGC |

| CA2 | CATCACTGGGGGTACGGCAAAC | GGGAAGTCCTTATGCCAGTGCT |

| CDX2 | GCCAAGTGAAAACCAGGACG | CAGAGAGCCCCAGCGTG |

| CEBPA | TCGGTGGACAAGAACAGCAA | CTGGCGGAAGATGCCCC |

| CEL | TGATGCTCACCATGGGGCGC | TGTACACGGCGCCCAGCTTC |

| CFTR | AGAGGTCGCCTCTGGAAAAGG | GCGCTGTCTGTATCCTTTCCTCA |

| GATA4 | CTCAGAAGGCAGAGAGTGTGT | CGGGAGGCGGACAGC |

| GLUCAGON | CCGAGGAAGGCGAGATTTCCCA | TCAGCATGTCTGCGGCCAAGT |

| INSULIN | GAGGCTTCTTCTACACACCC | CCACAATGCCACGCTTCTGC |

| NKX2.2 | GGTCCGGAGGAAGAGAACGA | AGACCGTGCAGGGAGTACTGA |

| NKX6.1 | CCTCATCAAGGATCCATTTTGTT | TGCTTCTTCCTCCACTTGGTC |

| PDX1 | ATGAACGGCGAGGAGCAGTA | TGGGTCCTTGTAAAGCTGCG |

| PNLIP | ACTGCCACGATGCTGCCACTT T | CACTGAAGCAGCCGAGTCTTTCGT |

| PTF1A | GGCCATCGGCTACATCAACT | ACCGGGTGCCCCGATG |

| SOX2 | TGTCAAGGCAGAGAAGAGAGTG | AGAGGCAAACTGGAATCAGGA |

| SOX9 | GCTCTGGAGACTTCTGAACGA | CCGTTCTTCACCGACTTCCT |

| SPINK1 | TGAAAATCGGAAACGCCAGACTTCT | CTCGCGGTGACCTGATGGGAT |

Mammary gland injection

Day 16 pancreatic progenitor organoid were treated with collagenase/dispase (Roche) and subsequently with accutase for 45 minutes at 37°C. Dissociated cells were resuspended with PTOM medium and 50% Matrigel (cell density 5×107 cells/ml), then the cell suspension was kept on ice. 0.3–0.5 million cells were injected into one mammary gland and No.4 and No.9 glands of 6–8 weeks old female NOD/SCID mice were used for injection. Standard animal care was provided during and after surgery, following the animal user protocol approved by the Animal Care Committee at UHN. Growth of transplants was monitored every week from four weeks after injection. No randomization was used but analyses were conducted in a blinded manner by three separate investigators. For monitoring in vivo tumorigenesis of progenitor organoid expressing oncogenes, progenitors were lentivirally-transduced and cultured in 3D for 16 days as described above. Then progenitor organoids were injected into mouse mammary gland and monitored as outlined above.

Tumor xenograft model

Passage 3 tumor organoids were cultured in 3D for 16 days then isolated and dissociated by enzymatic digestion. Cells from tumor organoids were resuspended in POTM with 50% Matrigel at a density of 105 cells/ml. 50,000 cells were injected at the flank of 6 weeks old female NSG mice following an institutionally approved protocol. Both flanks of mice were injected and standard animal cares were provided during and after surgery. Growth of transplants was monitored every week from two weeks after injection. Xenograft tumors were isolated 4–7 weeks after injection and reseeded in 3D following the protocol described above.

Statistical Analysis

Data from qPCR experiments and MTT proliferation assay were analyzed using t-test with Excel program. Organoid size and shape measurements were analyzed using t-test with Graphpad Prism program. Patient survival data were analyzed using a univariate Cox proportional hazards model with R program.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Muthuswamy laboratory for helpful suggestions and discussions. Dalia Barsyte-Lovejoy for helping with epigenetic drug screening experiments and members of the PanCuRx team including Dr. David Hedley for their support and assistance. This work was supported PanCuRx program, OICR; Cancer Research Society, Lee K Margaret Lau Chair for breast cancer research and Campbell Family Institute for Breast cancer research to SKM. The Structural Genomics Consortium is a registered charity (number 1097737) that receives funds from AbbVie, Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Canada Foundation for Innovation, Eshelman Institute for Innovation, Genome Canada, Innovative Medicines Initiative (EU/EFPIA) [ULTRA-DD grant no. 115766], Janssen, Merck & Co., Novartis Pharma AG, Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation, Pfizer, São Paulo Research Foundation-FAPESP, Takeda, and the Wellcome Trust. This was also funded in part by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the OMOHLTC.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

S.K.M. conceived and coordinated the project, designed experiments, and co-wrote the manuscript with L.H. L.H. also designed, performed and/or coordinated all experiments. A.H. contributed to pancreatic lineage committed precursor generation. I.J. contributed tumor organoid live imaging and manuscript preparation. M.B. contributed to tumor organoid immunofluorescent microscopy. I.L. contributed to collection of PDX tumors. N.N. contributed to organoid size measurement. C.N. contributed to pancreatic lineage committed precursor generation. R.W. contributed to human fetal pancreas studies. L.B.M. contributed to bioinformatics analysis for gene expressions. H.C.C contributed to experimental design. C.A contributed to epigenetic drug screening. S.E.K. contributed to studies of P53 and SOX9 localization in patient samples. D.J.R. contributed to studies of P53 and SOX9 localization in patient samples. A.A.C. contributed to studies of P53 and SOX9 localization in patient samples. S.C. contributed to studies of P53 and SOX9 localization in patient samples. D.F.C. contributed to studies of P53 and SOX9 localization in patient samples. M.R. contributed to pathological analysis on patient tumor and tumor organoids, and studies of P53 and SOX9 localization in patient samples. M.T. contributed to pathological analysis on patient tumor and tumor organoids, and studies of P53 and SOX9 localization in patient samples. S.G. contributed to obtaining patient resections for tumor organoid.

References

- 1.Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP. Biology and management of pancreatic cancer. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2008;84:478–497. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.103333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanji ZS, Gallinger S. Diagnosis and management of pancreatic cancer. CMAJ. 2013;185:1219–1226. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:607–620. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agbunag C, Lee KE, Buontempo S, Bar-Sagi D. Pancreatic duct epithelial cell isolation and cultivation in two-dimensional and three-dimensional culture systems. Methods in enzymology. 2006;407:703–710. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)07055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huch M, et al. Unlimited in vitro expansion of adult bi-potent pancreas progenitors through the Lgr5/R-spondin axis. The EMBO journal. 2013;32:2708–2721. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X, et al. Oncogenic transformation of diverse gastrointestinal tissues in primary organoid culture. Nature medicine. 2014;20:769–777. doi: 10.1038/nm.3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pagliuca FW, et al. Generation of functional human pancreatic beta cells in vitro. Cell. 2014;159:428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rezania A, et al. Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32:1121–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiesser JV, Wells JM. Generation of beta cells from human pluripotent stem cells: are we there yet? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1311:124–137. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jennings RE, et al. Development of the human pancreas from foregut to endocrine commitment. Diabetes. 2013;62:3514–3522. doi: 10.2337/db12-1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan FC, Wright C. Pancreas organogenesis: from bud to plexus to gland. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:530–565. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCracken KW, Wells JM. Molecular pathways controlling pancreas induction. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:656–662. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hick AC, et al. Mechanism of primitive duct formation in the pancreas and submandibular glands: a role for SDF-1. BMC Dev Biol. 2009;9:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riedel MJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characterisation of cells co-producing insulin and glucagon in the developing human pancreas. Diabetologia. 2012;55:372–381. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyttle BM, et al. Transcription factor expression in the developing human fetal endocrine pancreas. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1169–1180. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1006-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Outzen HC, Leiter EH. Transplantation of pancreatic islets into cleared mammary fat pads. Transplantation. 1981;32:101–105. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laitio M, Lev R, Orlic D. The developing human fetal pancreas: an ultrastructural and histochemical study with special reference to exocrine cells. Journal of anatomy. 1974;117:619–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nielsen SK, et al. Characterization of primary cilia and Hedgehog signaling during development of the human pancreas and in human pancreatic duct cancer cell lines. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2039–2052. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolodecik T, Shugrue C, Ashat M, Thrower EC. Risk factors for pancreatic cancer: underlying mechanisms and potential targets. Front Physiol. 2013;4:415. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang DK, Grimmond SM, Biankin AV. Pancreatic cancer genomics. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2014;24:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakravarty G, Rider B, Mondal D. Cytoplasmic compartmentalization of SOX9 abrogates the growth arrest response of breast cancer cells that can be rescued by trichostatin A treatment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:71–83. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.1.13952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chakravarty G, et al. Prognostic significance of cytoplasmic SOX9 in invasive ductal carcinoma and metastatic breast cancer. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011;236:145–155. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marusyk A, Almendro V, Polyak K. Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nature reviews. Cancer. 2012;12:323–334. doi: 10.1038/nrc3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waddell N, et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Beucken T, et al. Hypoxia promotes stem cell phenotypes and poor prognosis through epigenetic regulation of DICER. Nature communications. 2014;5:5203. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson AB, Denko N, Barton MC. Hypoxia induces a novel signature of chromatin modifications and global repression of transcription. Mutation research. 2008;640:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viale A, et al. Oncogene ablation-resistant pancreatic cancer cells depend on mitochondrial function. Nature. 2014;514:628–632. doi: 10.1038/nature13611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boj SF, et al. Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2015;160:324–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang B, Muthuswamy SK. Using three-dimensional acinar structures for molecular and cell biological assays. Methods in enzymology. 2006;406:692–701. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)06054-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods References

- 30.Nostro MC, et al. Stage-specific signaling through TGFbeta family members and WNT regulates patterning and pancreatic specification of human pluripotent stem cells. Development. 2011;138:861–871. doi: 10.1242/dev.055236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nostro MC, et al. Efficient generation of NKX6-1+ pancreatic progenitors from multiple human pluripotent stem cell lines. Stem Cell Report. 2015;4:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.