Abstract

Faecal incontinence (FI) is a disabling and frequent symptom since its prevalence can vary between 5% and 15% of the general population. It has a particular negative impact on quality of life. Many tools are currently available for the treatment of FI, from conservative measures to invasive surgical treatments. The conservative treatment may be dietetic measures, various pharmacological agents, anorectal rehabilitation, posterior tibial nerve stimulation, and transanal irrigation. If needed, patients may have miniinvasive approaches such as sacral nerve modulation or antegrade irrigation. In some cases, a surgical treatment is proposed, mainly external anal sphincter repair. Although these different therapeutic options are available, new techniques are arriving allowing new hopes for the patients. Moreover, most of them are non-invasive such as local application of an α1-adrenoceptor agonist, stem cell injections, rectal injection of botulinum toxin, acupuncture. New more invasive techniques with promising results are also coming such as anal magnetic sphincter and antropylorus transposition. This review reports the main current available treatments of FI and the developing therapeutics tools.

Keywords: Faecal incontinence, Treatment

Core tip: Faecal incontinence (FI) is a disabling and frequent symptom. Many tools are available for its treatment from conservative measures to invasive surgical treatments. Although different therapeutic options are currently available, new techniques are arriving allowing new hopes for the patients. This review reports the main current available treatments of FI and the developing therapeutics tools.

INTRODUCTION

Faecal incontinence (FI) is defined as a complaint of involuntary loss of flatus and/or liquid or solid stool via the anus[1]. Its prevalence can vary between 5% and 15% of the general population, especially depending on the patient’s age and gender[2]. Moreover, these rates are most probably underestimated since less than 25% of patients with FI report it to their physician[3]. As a debilitating condition it has considerable impact on patient quality of life (QOL), particularly from a sexual and social point of view[4].

Aetiologic factors for FI are mainly split between localized perineal pathologies and general pathologies (Table 1). Obstetric perineal lesions are the most frequent, including anal sphincter tears and stretch induced neuropathy[5]. Side effects of radiotherapy or chronic inflammatory bowel diseases can also lead to FI. General pathologies concerned include neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis[6] or medullary lesions, metabolic disorders (diabetes)[7] and systemic diseases (systemic sclerosis). Aetiological diagnosis is essential for the management of FI. Indeed, any specific treatment available can be used to target the pathology, and thus improve FI.

Table 1.

Main aetiologic factors for faecal incontinence

| Localized perineal pathologies |

| Sphincter injury |

| Traumatic lesion (obstetric lesion, sexual abuse) |

| Surgical lesion (anal fistula surgery, hemorrhoidectomy, anal sphincterotomy) |

| Anoperineal lesion in Crohn’s disease |

| Anal cancer |

| Pudendal neuropathy |

| Obstetric lesion |

| Dyschezia |

| Deficient rectal function |

| Chronic inflammatory bowel diseases |

| Radiation proctitis |

| Rectal cancer |

| Faecal impaction |

| Rectal surgery (anterior rectal resection, ileoanal pouch surgery) |

| Rectal prolapse |

| General pathologies |

| Acute or chronic diarrhea |

| Chronic inflammatory bowel diseases |

| Irritable bowel syndrome |

| Coeliac disease |

| Infectious diarrhea |

| Bile acid induced |

| Neurological diseases |

| Central (post stroke lesion, multiple sclerosis, medullary lesions) |

| Peripheral (diabetic or alcoholic neuropathy) |

| Systemic diseases (systemic sclerosis) |

Faecal continence relies on two systems: A resistive and a capacitive system. The rectum that is a reservoir for stool represents the capacitive system. The resistive system is made up of the anal sphincters and the pubococcygeus muscle that closes the anal canal and maintains optimal intra abdominal pressure. Continence is also tightly linked to a very elaborate sensory nervous system, capable of analysing the sense of urge as well as the exact contents of the rectum[8]. FI can result from the failure of one or more of these elements. Further useful examinations include anal endosonography to detect any damage to the anal sphincters, and anorectal manometry to measure compliance and rectal sensation as well as pelvic floor muscle strength. These examinations are sometimes completed with electromyography of the anal canal and measurement of pudendal nerve terminal motor latency to check them for damage. These examinations aim to identify defective mechanisms and set up appropriate healthcare.

Treatment has greatly progressed in recent years and the future holds interesting new therapies. This paper describes the current and future treatments for FI. The level of evidence of each current therapeutic modality, as summarized in Table 2, was given according to subdivisions of Level of Evidence as proposed by the Haute Autorité de Santé (French High Autority of Health) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Level of scientific evidence for current treatments in faecal incontinence according to the Haute Autorité de Santé (French High Autority of Health)

| Therapeutic modality | Levels of scientific evidence |

| Conservative treatment | |

| Hygiene and diet control | |

| Diet restriction | V |

| High fiber diet | II (Liquid stools) |

| I (Constipation) | |

| Pharmacological therapy | |

| Anti-motility drugs | I (Liquid stools) |

| Stool-bulking agents | IV |

| Cholestyramine | IV |

| Topical agents or oral treatment to enhance anal canal tone | V |

| Hormone replacement therapy | V |

| Suppositories, rectal irrigation, oral laxatives | I (Constipation) |

| Perineal rehabilitation | |

| Pelvic floor exercises | V |

| Anal electrostimulation | IV |

| Biofeedback therapy | II |

| Other conservative treatments | |

| Posterior tibial nerve stimulation | III |

| Transanal irrigation | I |

| Anal plugs | V |

| Minimally invasive treatment | |

| Sacral neuromodulation | IV |

| Antegrade irrigation | V |

| Anal radiofrequency | V |

| Intrasphincteric injections | V |

| Surgical treatment | |

| Sphincter repair | II |

| Graciloplasty | V |

| Artificial sphincter | V |

| Colostomy | V |

Table 3.

Level of scientific evidence (Haute Autorité de Santé, High Autority of Health)

| I | Large randomized controlled trials with undeniable results |

| II | Small randomized controlled trials and uncertain outcomes |

| III | Non-randomized trials with control groups contemporaries |

| IV | Comparative non-randomized groups with historical controls and case-control studies |

| V | No control groups, patient series |

| Case reports | |

| Expert recommandation |

CURRENT TREATMENTS

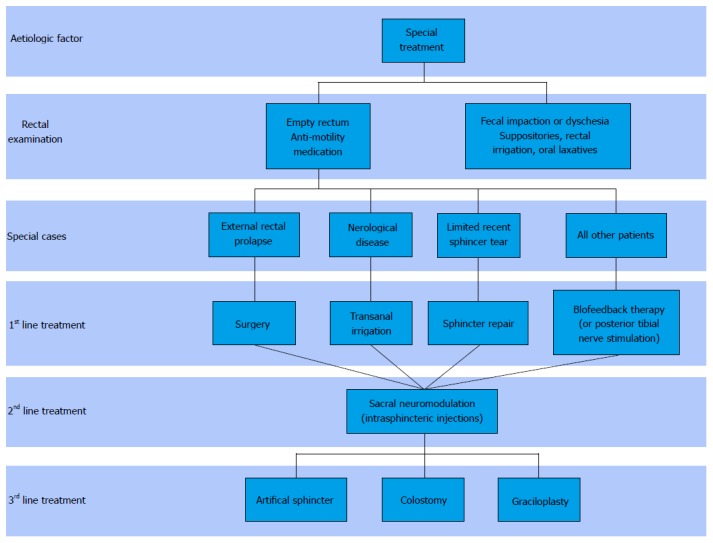

In order to offer targeted treatment, it is necessary to identify the pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for FI, but also the patient’s expectations. The aim is to improve continence and to reduce the impact of FI on the patient’s QOL. Currently, treatments revolve around three levels: Conservative treatment, minimally invasive treatment and surgical treatment. Figure 1 presents the current therapeutic strategy for the management of FI.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for faecal incontinence current treatment.

CONSERVATIVE TREATMENT

The first level in FI management may improve FI in over 60% of patients[9]. It is based on personal hygiene and diet control, the use of certain drugs, pelvic floor therapy, posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS), transanal irrigation (TAI) and the use of anal plugs.

Hygiene and diet control

FI management is, above all, based on regularizing stool frequency and consistency. Use of a bowel diary combined with a food diary may help identify food that aggravates stool leakage, such as caffeine, fruit and vegetables, alcohol, or spicy food[10]. Cutting out these foods may alleviate FI for some patients even though definitive evidence is lacking[11]. A high fibre diet, or the consumption of mucilage can, in some cases, improves faecal continence by improving stool consistency, especially for patients with liquid stools or with associated constipation. In a randomized controlled study, Bliss et al[12] showed a 50% reduction in the number of FI episodes per week after daily consumption of Psyllium compared to placebo.

Pharmacological therapy

Several different medications can be used to regularize stool frequency, improve stool consistency or enhance anal canal tone. Anti-motility drugs (loperamide, codeine) have been scientifically proved to be efficient for patients suffering from FI[13]. These molecules seem to be the most useful in cases of loose of liquid stools by reducing stool frequency and thus the number of incontinence episodes. Indeed, in a double-blind cross-over trial comparing loperamide with placebo, about 60% of the patients had less incontinence episodes with loperamide than with placebo[14]. Their efficacy has not been proved in the cases of normal or hard stools.

Stool-bulking agents, such as mucilage, are also useful in management of FI with loose stool even if these practice is not supported by strong scientific studies. These synthetic fibres improve stool consistency by increasing water absorption by stools. Even though their efficacy has not been rigorously proved scientifically, mucilages are still recommended in clinical practice[15], particularly combined with other conservative treatments[16].

Ion-exchange resins may also be tried in FI management. Cholestyramine, in particular, has been shown to improve stool frequency and consistency in patients who have an FI in combination with diarrhea[17].

Several pharmaceutical substances have been studied in FI that aim to enhance anal canal tone and thus reduce the number of incontinence episodes. Topical agents such as phenylephrine[18-20], or oral treatments such as diazepam, amitriptyline or sodium valproate[21-23] have shown some efficacy in this indication, sometimes up to 100% of treated patients. However, given the small number of studies and the potentially disabling adverse effects, these treatments are not recommended in clinical practice.

Even though some data suggest a potential efficacy of hormone replacement therapy on FI in postmenopausal women, about 65% of treated patients[24], it is not currently recommended due to insufficient scientific proof[15].

Finally, in cases where FI is associated with rectal emptying disorders, help with rectal emptying is an essential point in incontinence management. Suppositories and rectal irrigation, combined with oral laxatives if necessary, all contribute towards eliminating faecal impaction, thus allowing a decrease of 35% in the number of FI episodes and of 42% in faecal soiling especially in geriatric patients[25].

Perineal rehabilitation

If the first line medical treatment fails, perineal rehabilitation strategies can be offered. These physiotherapy techniques are based on re-training faecal continence and target both anal sphincters and abdominal muscles. Anorectal manometry is used to determine the most adequate therapy.

These techniques mainly involve pelvic floor exercises, anal electrostimulation and biofeedback. Pelvic floor exercises are muscle strengthening exercises, especially of the pubococcygeus using Kegel exercises[26]. Anal electrostimulation uses surface electrodes on the perineum which either stimulate muscular contraction directly or indirectly via stimulation of peripheral nerves[27]. Biofeedback therapy helps to increase voluntary contraction of the external anal sphincter, but also to synchronize the different perineal muscles in response to a rectal stimulus in order to maintain continence[28]. This technique uses instruments capable of monitoring sphincter contractions and thus helps with training.

Perineal rehabilitation strategies have shown heterogeneous efficacy on FI depending on the study. Despite anal electrostimulation having been shown to be beneficial in this indication[27], its use alone is not recommended[15]. Biofeedback therapy seems to be the most widely used and the most efficient, with success rates between 50% and 90% that were maintained up to 24 mo[29,30]. Even though there are discordant results in scientific literature[31], these perineal rehabilitation techniques are still recommended in second line for FI management.

PTNS

PTNS appears to be a simple technique to use, it is non invasive and not costly. Two methods of stimulation exist: Percutaneous, using needle-electrodes, and transcutaneous using adhesive surface electrodes. Two electrodes are placed on the posterior tibial nerve pathway, and linked to a stimulator that can be controlled by the patient. The mechanism involved in FI treatment remains poorly understood but certainly involves afferences and somato-sympathetic reflexes. Even though there are only a few studies published with relevant different results for the two methods of stimulation[32,33], this technique reduced FI episodes for 63% to 82% of patients treated, with a follow-up of 1 to 30 mo[34]. To this day, there is no consensus concerning treatment duration, stimulation frequency/rythm or need for repeating treatment. However, this technique may be recommended for patients who do not respond to the other non-invasive techniques or suffering from FI without transit disorders[15].

TAI

TAI is currently recommended in second line management, after dietary measures and first-line medical treatment, in patients suffering from chronic neurological diseases[15]. The aim is to empty the colon of the maximum of faecal matter using regular irrigation, optimized using an inflatable rectal balloon catheter to make the system watertight. This method improves digestive symptoms, including FI, in between 40% and 75% of patients suffering from chronic neurological diseases[35-37]. It also helps to significantly enhance the patients’ QOL, by significantly increasing their independence, and seems to decrease the risk of urinary infections[38]. However, this treatment can only work if the patient and their family are committed.

Moreover, this device may also be used in non-neurological patients as demonstrated by recent studies in patients suffering from anterior resection syndrome. For example, in the study by Rosen et al[39] after a mean follow-up of 29 mo, TAI allowed a significant improvement in the number of stools, the Cleveland Incontinence Score, and in QOL. A study by Koch et al[40] using a device from another manufacturer in thirty patients, showed a complete improvement in 57% of patients.

Anal plugs

Anal plugs come in different sizes and are made from different substances, they are easy to use and can be of great help on a daily basis. Tolerating anal plugs can be a problem but can be improved depending on the type of plug used[41,42]. Anal plugs have shown to be efficient on FI and can be used as a supplementary treatment to other therapies. Indeed, when patients tolerate them, up to 65% of patients reported the absence of soiling episodes[43].

Minimally invasive treatment: When conservative therapy has not been sufficient, some minimally invasive methods can be proposed to improve faecal continence. Currently, this type of therapy is mainly represented by sacral neuromodulation (SNM). Other techniques exist but they are more confidential, such as antegrade colon irrigation, anal radiofrequency treatment or intrasphincteric injections.

SNM

SNM is proposed to patients suffering from at least one FI episode a week and for whom conservative treatment, combining hygiene/dietary control and biofeedback, has failed[15]. The mechanism of action remains poorly understood to this day[44], although it seems to involve several mechanisms at different levels. Indeed, it could act on continence via somato-sympathetic medullary reflexes[45], but also via the activation or inhibition of areas of the brain responsible for continence[46]. This cerebral mechanism was also discussed in a recent study that showed a persistent efficacy of SNM even after stimulation had been stopped, suggesting that a long period of SNM could bring about a certain neuroplasticity[47].

This treatment stimulates the sacral nerves on a permanent basis via an electrode implanted in contact with the nerve where it exits the sacral foramen. The device is set up in two stages. The first stage, called peripheral nerve evaluation (PNE), is a test period. For 2 to 3 wk, the electrode is implanted, the most often in contact with the S3 root[48,49], and linked to an external stimulator. Stimulation parameters can therefore be modified to obtain sufficient efficacy on FI. The second stage, involving definitive implantation of the pulse generator under the skin, is only carried out if the patient has a 50% reduction of FI episodes with PNE[15].

On the whole, in a recent literary review, SNM seems to be efficient in approximately 60% of patients suffering from FI, for whom conservative therapy failed. The therapeutic effect persists over time, even though a 10% reduction in efficacy was noted during the first 5 years[50]. At the same time, 70% to 80% of patients who had this treatment declared that it had improved their QOL[51-53].

Indications for SNM are numerous. It can be recommended in cases of idiopathic FI, or FI linked to post-obstetric perineal injuries, such as anal sphincter tears or stretch-induced neuropathy[54-56]. It is also recommended in cases of FI of neurological origin, either central or peripheral[57-59]. Patients with systemic sclerosis suffering from FI can also benefit from SNM, although recent data have shown a lack of efficacy for this indication[60]. Finally, patients suffering from double incontinence, urinary and faecal, seem to respond to SNM[61,62]. Other aetiologies of FI are not currently considered to be indications for SNM[15], even though there is some data, particularly for Crohn’s disease[63].

Several studies have tried to determine predictive factors for SNM efficacy on FI. Factors such as age, stool consistency, symptom duration, pre-therapeutic manometric data, or obtaining a motor or sensory response at a low stimulation threshold have all been suggested to be predictive of a good or bad response to SNM. However, despite the fact that data is sometimes contradictory and that recent studies have not been able to identify any significant predictive factors[64], SNM should be considered to be a therapeutic option for all patients suffering from FI, except when contraindicated[65].

Antegrade irrigation (malone)

Based on the same principal as TAI, antegrade irrigation aims to restore continence by keeping the colon empty. The surgical procedure creates a caecostomy allowing patients to perform colon irrigation themselves.

With this technique 80% to 90% of patients reported pseudo continence, with, however, some complications that sometimes led to explantation of the device[66,67]. This method has also been shown to be efficient when combined with an artificial urinary sphincter in patients suffering from double incontinence[68].

More recently a technique of percutaneous endoscopic caecostomy has been proposed with interesting results but further studies are necessary to assess its success rate in the treatment of FI[69].

Anal radiofrequency (SECCA)

Temperature-controlled radiofrequency energy delivery to the anal canal (SECCA procedure) is an endoscopic technique mainly used for passive FI, with a success rate of close to 70%[70]. It is based on forming retractile fibrosis, with deposition of collagen and shrinkage in the internal anal sphincter. However, published results are sometimes contradictory[71] and in the long term its efficacy seems to rapidly decrease[72].

Intrasphincteric injections

In order to increase anal resting pressure, several different bulking agents, injected either into the submucosal or intersphincteric space, have been tested on FI[73]. Efficacy varied depending on the product tested[74-76], but only two studies compared bulking agent injections with sham injections. Dextranomer microspheres in stabilised hyaluronic acid (NASHA Dx) was the only product that showed a significant difference vs placebo. Indeed, a 50% or more reduction of the number of FI episodes was observed in 52% of patients who received NASHA Dx and 31% of patients who received placebo[77]. A large number of adverse effects were reported, but most of them were not serious. On the other hand, despite a significant improvement on continence, injections with silicone elastomers showed no significant difference vs sham injections, underlining the noticeable placebo effect of this procedure[78]. Finally, in a randomized clinical trial studying an injectable silicone biomaterial (PTP™), the success rate was 69% with endoanal ultrasound guidance and 40% without[79]. So, this technique seems to give better results when the injections are performed under endoanal ultrasound guidance.

Surgical treatment: Several different surgical solutions can be offered to patients with severe FI[80]. The most frequently used technique is sphincteroplasty. Given the good results obtained with conservative treatment and SNM, indications for surgical treatment have become relatively rare.

Sphincter repair

Sphincter repair is indicated in patients with symptomatic FI associated with external anal sphincter damage[15]. It aims to restore, at least partially, the anatomical barrier necessary for faecal continence and is recommended in priority in patients with recent sphincter injury that does not exceed half the circumference[81].

Several different surgical techniques have been described, notably direct repair and overlapping sphincter repair, but no significant difference was demonstrated[82,83]. Performing a temporary protective colostomy did not show any probing results either[84].

Short-term efficacy on FI is close to 70%[85]. This efficacy tends however, to decrease with time[86]. Despite this, patient satisfaction and QOL remained high even on a long-term basis[87]. Furthermore, in cases of persistent and debilitating FI, it is possible to repeat surgical repair on the external anal sphincter[88].

Graciloplasty

Techniques of muscle transposition aim to replace anal sphincters, especially in cases where sphincter damage is too severe. Several techniques have been described but graciloplasty, dynamic or not, is the most studied and used technique.

The success rate of graciloplasty is between 60% and 90%[89-93]. Originally data seemed to suggest that dynamic graciloplasty was the most efficient, however a recent study reported an identical success rate for both techniques[94].

Despite a high rate of complications, between 35% and 75%, (infections, wound healing, pain, stoma problems, constipation) and the common necessity for further surgical procedures[95-98], these methods of muscle transposition remain efficient on anal incontinence, with a success rate which persists over time[99,100]. Furthermore, patients who have had graciloplasty report an improved QOL[101].

However, in clinical practice, the indication of these techniques remains limited[15].

Artificial sphincter

An artificial anal sphincter, whatever the model, is made up of a band around the anal canal, a pump placed in the external genital organs, and a pressure-regulated balloon[102]. It is especially indicated in case of severe sphincter damage and/or severe local neurological lesions.

In a recent meta-analysis, the technique’s success rate on FI was 75% in the first three years, followed by a progressive decrease since it was only 55% after 5 years of follow-up[103]. Other studies have shown more disappointing long-term results, with only 3 out of 25 patients in the study by Altomare et al[104] and 4 out of 21 patients in the study by Darnis et al[105] showing a good functional result after 3 years of follow-up.

Along with these contrasting results, morbidity of the technique is far from being negligible with a rate of explantation of the device between 24% and 39% depending on the length of follow-up[103]. The majority of complications are infections, perianal pain, and, on a long-term basis, problems with rectal emptying. In a recent case study, all 21 patients treated had at least one complication during the 38-mo follow-up[105].

This high rate of complications combined with moderate efficacy limits the use of this technique in common practice.

Colostomy

Often reserved for patients for whom all the other treatments have failed, colostomy can be indicated to treat severe FI[106]. Comparison of QOL between patients with a colostomy and those suffering from FI, showed a higher social function and an improvement of the coping, embarrassment, lifestyle scales and depression scales in the colostomy group[107]. In the same way, after colostomy, patients who initially suffered from FI granted a high level of satisfaction, in spite of initial apprehension and some complications reported (bleeding, parastomal hernia, mucus leakage)[108]. Therefore, this technique, used in strategic FI management, should not be excluded as a failure since in the end it improves patient QOL and grants them more independence.

PERSPECTIVES

Numerous novel therapies are arriving in the field of the treatment of FI allowing patients to new hopes for this disabling symptom. These novel therapies may be local application of NRL001 (an α1-adrenoceptor agonist), stem cell injection, magnetic anal sphincter, antropylorus transposition, or other new options.

Local application of an α1 -adrenoceptor agonist

Alpha1-adrenoceptors have been tested for years since they are known to induce a contractile response of the human internal anal sphincter[109]. However because of their poor clinical tolerance (modifications of cardiovascular parameters), their use didn’t initially spread in clinical practice. More recently, since NRL001 has a dose-dependent effect, the concentration was modified to improve tolerance. However, to date, only phase-I studies are available[110-113]. We are currently waiting for the future results of the “Libertas” study that is a multicentre Phase II, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel group. It will evaluate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of locally applied NRL001 in patients with FI[114].

Stem cell injection

The use of stem cell can be done in two main different ways: Direct injections in the sphincter or peri-anal implantation of a bioengineered sphincter. Stem cell involved may be mesenchymal stem cell or muscle-derived stem cell. For the moment, most of the studies have been done in animal models. The first study reporting that autologous muscle-derived stem cell grafts (in a rat model) may be a new tool for improving anal sphincter function was published in 2007[115]. Then, other studies have demonstrated the feasibility of the use of stem cells in a rat model, with myoblast[116] and with mesenchymal stem cells[117,118]. Another way to use stem cell is the perinanal implantation of a bioengineered sphincter. In an original study, isolated human internal anal sphincter circular smooth muscle cells and human enteric neuronal progenitor cells were use to construct a bioengineered internal anal sphincter. After maturation, it was implanted in the perianal region of athymic rats and retrieved from the animal after 4 wk. The implantation was well tolerated in all animals and there were no postoperative complications. Normal stooling was observed during the implantation period. After the 4 wk period, it was observed that implanted bioengineered sphincters were adherent to the perirectal rat tissue and appeared healthy and pink and immunohistochemical data showed neovascularization[119]. A particular interest of this model is that the bioengineered IAS may overcome the problems of foreign bodies in the perineum since it is purely made from autologous tissue. Further studies will be necessary to confirm this concept.

To date, only two works describe the use of stem cell in humans. The first one was published in 2010 and included 10 women suffering from FI due to obstetric anal sphincter injury. In this pilot study, autologous myoblasts were cultured from a pectoralis muscle biopsy, harvested, and then injected into the external anal sphincter defect under ultrasound guidance. At 12 mo a significant improvement in the Wexner score and in the QOL were observed. The anal squeeze pressures did rise significantly at 1 mo and 6 mo post-injection without persistence at 12 mo. The procedure was well tolerated and no adverse events were observed[120]. The second case, published in 2013, has reported one case of injection of myoblast also obtained from a sample of the quadriceps muscle. The patient was a 20-year old male with FI due to an old external anal sphincter rupture in a road accident[121]. Although this work also showed encouraging results, data are still scarce and these two studies essentially demonstrate the feasibility in humans. Further studies will be needed to confirm the feasibility of stem cell injection in FI and to assess the potential long term success of this method that is for the moment limited to experimented centres.

Magnetic anal sphincter

The Fenix® magnetic anal sphincter operates on the principle of a reverse stent system; it is composed of a magnetic bead that creates a negative pressure around the tube it encircles. The device is made of magnetic balls tied together by titanium threads. Various magnetic sphincter lengths are available to accommodate the individual variations of anal circumference. This sphincter is designed to enhance the function of the anal sphincters without causing obstruction. It is functional immediately after implantation. During stool evacuation, the patient strains in a physiological way to create a sufficient force to separate the magnetic balls and to open the anal canal permitting thus the passage of stools.

The first feasibility study was published in 2010 and included results for 14 patients from[122]. The authors described a simple technique with a low morbidity (mainly represented by surgical site infections). Compared to the conventional artificial sphincter, the operative time and duration of hospitalization were much shorter. Since this first study, the results of the Fenix® magnetic anal sphincter device on FI have been reported in the literature, but few studies are currently available. In 2012, Wong et al[123] reported results from a single-center non-randomized study showing that the magnetic anal sphincter was as effective as sacral nerve stimulation in improving symptoms and QOL in patients suffering from faecal continence. Moreover, the morbidity was similar with the two techniques. Then, new studies have confirmed the success rate of this device, in 23 patients with a median follow-up of 17.6 mo in the study of Barussaud et al[124] and in 18 patients with a follow-up from 353 d to 738 d in the study of Pakravan et al[125]. In both studies, symptoms, FI severity scores and QOL were significantly improved. However, although it brings promising results, the efficacy of the magnetic anal sphincter needs to be confirmed in larger and randomized studies with longer follow-up.

Antropylorus transposition

Ger et al[126] published the first report of the transposition of the antropyloric valve as a living sphincter at the end of an ileostomy in 1982. After this first publication, successive other works demonstrated the feasibility and the interest of this technique in animals[127-129]. More recently, some studies have been published about this technique in adult patients. The first preliminary report in human was published in 2011[130]. Then, Goldsmith et al[130] published successive studies on this technique demonstrating the feasibility and the success rate of this technique on clinical and manometric parameters in patients requiring anal replacement. In particular, they demonstrated in a study in 17 patients, after a median follow-up of 18 mo, a definite tone of the transposed graft on digital examination, an improvement in the St Mark incontinence score and in the QOL score (SF-36) associated with a significant rise in the postoperative resting neosphincter pressure[131-133].

However, although this new technique is very interesting, it remains a surgical invasive approach and it is, for the moment, at a very early stage of its development. Further larger studies with long-term follow-up will be necessary to evaluate the validity and the place of this technique.

OTHER TREATMENTS

Toxine

Injection of Botulinum Toxin (BT) into the detrusor muscle is used for years by urologists to improve overactive bladder. In FI, especially in urge incontinence, a same mechanism may be hypothesized based on a rectal contractile disorder. A first study has been published to assess the efficacy of intrarectal injections of BT in the treatment of FI[134]. This prospective pilot study included 6 patients with high-amplitude contractions of the intact native rectum or of the reservoir (4 patients had a proctectomy for rectal cancer). Anal sphincters were intact in most of the patients. In this study, all the patients reported a clinical improvement based on the Cleveland Clinic Score at 3-6 mo that was sustained at 6 mo. Manometric data showed a decrease of the mean amplitude of contractions whereas the frequency of contractions remained unaffected by the BT injections. These results are interesting and encouraging, especially because it is a simple and non-invasive treatment. However, its efficacy needs to be demonstrated in larger studies with selected patients.

Vaginal bowel control system

A vaginal bowel-control system has been reported in the treatment of FI. This device (Eclipse System) is a non-invasive, non-surgical therapeutic option. It consists of a vaginal insert with a pressure-regulated pump. The insert is made of a silicone-coated stainless steel base balloon that is posteriorly directed. In the prospective study of Richter including 110 patients, the intention-to-treat success rate at 1 mo was 78.7% and the success rate at 3 mo was 86.4%[135]. A significant improvement was also observed and no serious adverse effects were reported (mainly pelvic cramping or discomfort). This device is simple to use and non invasive and self-managed by the patients. Further studies will be necessary to determine the place of this device in the therapeutic algorithm of FI.

Acupuncture

The effect of acupuncture on FI has been reported by an Italian study[136]. In this pilot study, 15 female patients were submitted to one acupuncture treatment per week for a 10-wk period, and a control session was repeated once per month up to 7 mo for six patients. After the 10-wk period, a significant improvement was observed with an overall mean continence score in the 15 patients from 10 (3-21) to zero (0-7). The continence index available in 14 patients at about 18 mo after start of treatment was 1 (0-8). Concerning manometric parameters, a significant increase was observed in the resting anal pressure and in the ability to sustain the squeeze pressure whereas the maximal sphincter squeeze pressure remained unchanged.

CONCLUSION

FI is a common and disabling symptom. It is often reported by the patients as embarrassing to report to their health care providers leading to an underestimated prevalence. Several tools are currently available for the treatment of FI. The therapeutics modalities are mainly conservative and mini-invasive, but may sometimes need a surgical invasive approach. However, different now therapeutic approach are currently developing, most of them being conservative, leading to optimistic perspectives for patients suffering from FI.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 20, 2015

First decision: August 22, 2015

Article in press: December 11, 2015

P- Reviewer: Miheller P S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

References

- 1.Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1510–1518. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macmillan AK, Merrie AE, Marshall RJ, Parry BR. The prevalence of fecal incontinence in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1341–1349. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faltin DL, Sangalli MR, Curtin F, Morabia A, Weil A. Prevalence of anal incontinence and other anorectal symptoms in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12:117–120; discussion 121. doi: 10.1007/pl00004031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damon H, Guye O, Seigneurin A, Long F, Sonko A, Faucheron JL, Grandjean JP, Mellier G, Valancogne G, Fayard MO, et al. Prevalence of anal incontinence in adults and impact on quality-of-life. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamm MA. Obstetric damage and faecal incontinence. Lancet. 1994;344:730–733. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caruana BJ, Wald A, Hinds JP, Eidelman BH. Anorectal sensory and motor function in neurogenic fecal incontinence. Comparison between multiple sclerosis and diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:465–470. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bytzer P, Talley NJ, Leemon M, Young LJ, Jones MP, Horowitz M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with diabetes mellitus: a population-based survey of 15,000 adults. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1989–1996. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.16.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouvier M. [Physiology of fecal continence and defecation] Arch Int Physiol Biochim Biophys. 1991;99:A53–A63. doi: 10.3109/13813459109145917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demirci S, Gallas S, Bertot-Sassigneux P, Michot F, Denis P, Leroi AM. Anal incontinence: the role of medical management. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:954–960. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73356-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croswell E, Bliss DZ, Savik K. Diet and eating pattern modifications used by community-living adults to manage their fecal incontinence. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37:677–682. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3181feb017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen JL, Bliss DZ, Peden-McAlpine C. Diet strategies used by women to manage fecal incontinence. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2006;33:52–61; discussion 61-62. doi: 10.1097/00152192-200601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bliss DZ, Savik K, Jung HJ, Whitebird R, Lowry A, Sheng X. Dietary fiber supplementation for fecal incontinence: a randomized clinical trial. Res Nurs Health. 2014;37:367–378. doi: 10.1002/nur.21616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer KR, Corbett CL, Holdsworth CD. Double-blind cross-over study comparing loperamide, codeine and diphenoxylate in the treatment of chronic diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:1272–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Read M, Read NW, Barber DC, Duthie HL. Effects of loperamide on anal sphincter function in patients complaining of chronic diarrhea with fecal incontinence and urgency. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:807–814. doi: 10.1007/BF01391374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitton V, Soudan D, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L, Bouvier M, Faucheron JL, Leroi AM, Meurette G, Pigot F, Damon H. Treatments of faecal incontinence: recommendations from the French national society of coloproctology. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:159–166. doi: 10.1111/codi.12410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sjödahl J, Walter SA, Johansson E, Ingemansson A, Ryn AK, Hallböök O. Combination therapy with biofeedback, loperamide, and stool-bulking agents is effective for the treatment of fecal incontinence in women - a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:965–974. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.999252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Remes-Troche JM, Ozturk R, Philips C, Stessman M, Rao SS. Cholestyramine--a useful adjunct for the treatment of patients with fecal incontinence. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:189–194. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0391-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JS, Kang SB, Kim DW, Namgung HW, Kim HL. The efficacy and adverse effects of topical phenylephrine for anal incontinence after low anterior resection in patients with rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1319–1324. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badvie S, Andreyev HJ. Topical phenylephrine in the treatment of radiation-induced faecal incontinence. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2005;17:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carapeti EA, Kamm MA, Nicholls RJ, Phillips RK. Randomized, controlled trial of topical phenylephrine for fecal incontinence in patients after ileoanal pouch construction. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1059–1063. doi: 10.1007/BF02236550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoji Y, Kusunoki M, Yanagi H, Sakanoue Y, Utsunomiya J. Effects of sodium valproate on various intestinal motor functions after ileal J pouch-anal anastomosis. Surgery. 1993;113:560–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maeda K, Maruta M, Sato H, Masumori K, Matsumoto M. Effect of oral diazepam on anal continence after low anterior resection: a preliminary study. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:15–18. doi: 10.1007/s101510200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santoro GA, Eitan BZ, Pryde A, Bartolo DC. Open study of low-dose amitriptyline in the treatment of patients with idiopathic fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1676–1681; discussion 1681-1682. doi: 10.1007/BF02236848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donnelly V, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C. The influence of oestrogen replacement on faecal incontinence in postmenopausal women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:311–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chassagne P, Jego A, Gloc P, Capet C, Trivalle C, Doucet J, Denis P, Bercoff E. Does treatment of constipation improve faecal incontinence in institutionalized elderly patients? Age Ageing. 2000;29:159–164. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park SH, Kang CB, Jang SY, Kim BY. [Effect of Kegel exercise to prevent urinary and fecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women: systematic review] J Korean Acad Nurs. 2013;43:420–430. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2013.43.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norton C, Gibbs A, Kamm MA. Randomized, controlled trial of anal electrical stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:190–196. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norton C, Cody JD. Biofeedback and/or sphincter exercises for the treatment of faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD002111. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002111.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heymen S, Scarlett Y, Jones K, Ringel Y, Drossman D, Whitehead WE. Randomized controlled trial shows biofeedback to be superior to pelvic floor exercises for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1730–1737. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b55455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartlett L, Sloots K, Nowak M, Ho YH. Biofeedback for fecal incontinence: a randomized study comparing exercise regimens. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:846–856. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182148fef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norton C, Chelvanayagam S, Wilson-Barnett J, Redfern S, Kamm MA. Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback for fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George AT, Kalmar K, Sala S, Kopanakis K, Panarese A, Dudding TC, Hollingshead JR, Nicholls RJ, Vaizey CJ. Randomized controlled trial of percutaneous versus transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation in faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2013;100:330–338. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leroi AM, Siproudhis L, Etienney I, Damon H, Zerbib F, Amarenco G, Vitton V, Faucheron JL, Thomas C, Mion F, et al. Transcutaneous electrical tibial nerve stimulation in the treatment of fecal incontinence: a randomized trial (CONSORT 1a) Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1888–1896. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas GP, Dudding TC, Rahbour G, Nicholls RJ, Vaizey CJ. A review of posterior tibial nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:519–526. doi: 10.1111/codi.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Del Popolo G, Mosiello G, Pilati C, Lamartina M, Battaglino F, Buffa P, Redaelli T, Lamberti G, Menarini M, Di Benedetto P, et al. Treatment of neurogenic bowel dysfunction using transanal irrigation: a multicenter Italian study. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:517–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faaborg PM, Christensen P, Kvitsau B, Buntzen S, Laurberg S, Krogh K. Long-term outcome and safety of transanal colonic irrigation for neurogenic bowel dysfunction. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:545–549. doi: 10.1038/sc.2008.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ausili E, Focarelli B, Tabacco F, Murolo D, Sigismondi M, Gasbarrini A, Rendeli C. Transanal irrigation in myelomeningocele children: an alternative, safe and valid approach for neurogenic constipation. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:560–565. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christensen P, Bazzocchi G, Coggrave M, Abel R, Hultling C, Krogh K, Media S, Laurberg S. A randomized, controlled trial of transanal irrigation versus conservative bowel management in spinal cord-injured patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:738–747. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosen H, Robert-Yap J, Tentschert G, Lechner M, Roche B. Transanal irrigation improves quality of life in patients with low anterior resection syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e335–e338. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koch SM, Rietveld MP, Govaert B, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG. Retrograde colonic irrigation for faecal incontinence after low anterior resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:1019–1022. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0719-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfrommer W, Holschneider AM, Löffler N, Schauff B, Ure BM. A new polyurethane anal plug in the treatment of incontinence after anal atresia repair. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2000;10:186–190. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1072354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norton C, Kamm MA. Anal plug for faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2001;3:323–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2001.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deutekom M, Dobben AC. Plugs for containing faecal incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD005086. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005086.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gourcerol G, Vitton V, Leroi AM, Michot F, Abysique A, Bouvier M. How sacral nerve stimulation works in patients with faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e203–e211. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vitton V, Abysique A, Gaigé S, Leroi AM, Bouvier M. Colonosphincteric electromyographic responses to sacral root stimulation: evidence for a somatosympathetic reflex. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:407–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheldon R, Kiff ES, Clarke A, Harris ML, Hamdy S. Sacral nerve stimulation reduces corticoanal excitability in patients with faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1423–1431. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Altomare DF, Giannini I, Giuratrabocchetta S, Digennaro R. The effects of sacral nerve stimulation on continence are temporarily maintained after turning the stimulator off. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:e741–e748. doi: 10.1111/codi.12418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dudding TC, Parés D, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Predictive factors for successful sacral nerve stimulation in the treatment of faecal incontinence: a 10-year cohort analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:249–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melenhorst J, Koch SM, Uludag O, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG. Sacral neuromodulation in patients with faecal incontinence: results of the first 100 permanent implantations. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:725–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thin NN, Horrocks EJ, Hotouras A, Palit S, Thaha MA, Chan CL, Matzel KE, Knowles CH. Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of neuromodulation in the treatment of faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1430–1447. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Damon H, Barth X, Roman S, Mion F. Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence improves symptoms, quality of life and patients’ satisfaction: results of a monocentric series of 119 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:227–233. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1558-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Devroede G, Giese C, Wexner SD, Mellgren A, Coller JA, Madoff RD, Hull T, Stromberg K, Iyer S. Quality of life is markedly improved in patients with fecal incontinence after sacral nerve stimulation. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2012;18:103–112. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e3182486e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duelund-Jakobsen J, van Wunnik B, Buntzen S, Lundby L, Baeten C, Laurberg S. Functional results and patient satisfaction with sacral nerve stimulation for idiopathic faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:753–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan MK, Tjandra JJ. Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence: external anal sphincter defect vs. intact anal sphincter. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1015–1024; discussion 1024-1025. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boyle DJ, Knowles CH, Lunniss PJ, Scott SM, Williams NS, Gill KA. Efficacy of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence in patients with anal sphincter defects. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1234–1239. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819f7400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brouwer R, Duthie G. Sacral nerve neuromodulation is effective treatment for fecal incontinence in the presence of a sphincter defect, pudendal neuropathy, or previous sphincter repair. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:273–278. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181ceeb22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kenefick NJ, Vaizey CJ, Nicholls RJ, Cohen R, Kamm MA. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence due to systemic sclerosis. Gut. 2002;51:881–883. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holzer B, Rosen HR, Novi G, Ausch C, Hölbling N, Schiessel R. Sacral nerve stimulation for neurogenic faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2007;94:749–753. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jarrett ME, Matzel KE, Christiansen J, Baeten CG, Rosen H, Bittorf B, Stösser M, Madoff R, Kamm MA. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence in patients with previous partial spinal injury including disc prolapse. Br J Surg. 2005;92:734–739. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Butt SK, Alam A, Cohen R, Krogh K, Buntzen S, Emmanuel A. Lack of effect of sacral nerve stimulation for incontinence in patients with systemic sclerosis. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:903–907. doi: 10.1111/codi.12969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.El-Gazzaz G, Zutshi M, Salcedo L, Hammel J, Rackley R, Hull T. Sacral neuromodulation for the treatment of fecal incontinence and urinary incontinence in female patients: long-term follow-up. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:1377–1381. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0745-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leroi AM, Michot F, Grise P, Denis P. Effect of sacral nerve stimulation in patients with fecal and urinary incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:779–789. doi: 10.1007/BF02234695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vitton V, Gigout J, Grimaud JC, Bouvier M, Desjeux A, Orsoni P. Sacral nerve stimulation can improve continence in patients with Crohn’s disease with internal and external anal sphincter disruption. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:924–927. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roy AL, Gourcerol G, Menard JF, Michot F, Leroi AM, Bridoux V. Predictive factors for successful sacral nerve stimulation in the treatment of fecal incontinence: lessons from a comprehensive treatment assessment. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:772–780. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maeda Y, O’Connell PR, Lehur PA, Matzel KE, Laurberg S. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence and constipation: a European consensus statement. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:O74–O87. doi: 10.1111/codi.12905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sinha CK, Grewal A, Ward HC. Antegrade continence enema (ACE): current practice. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:685–688. doi: 10.1007/s00383-008-2130-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hoekstra LT, Kuijper CF, Bakx R, Heij HA, Aronson DC, Benninga MA. The Malone antegrade continence enema procedure: the Amsterdam experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1603–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bar-Yosef Y, Castellan M, Joshi D, Labbie A, Gosalbez R. Total continence reconstruction using the artificial urinary sphincter and the Malone antegrade continence enema. J Urol. 2011;185:1444–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duchalais E, Meurette G, Mantoo SK, Le Rhun M, Varannes SB, Lehur PA, Coron E. Percutaneous endoscopic caecostomy for severe constipation in adults: feasibility, durability, functional and quality of life results at 1 year follow-up. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:620–626. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Frascio M, Mandolfino F, Imperatore M, Stabilini C, Fornaro R, Gianetta E, Wexner SD. The SECCA procedure for faecal incontinence: a review. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:167–172. doi: 10.1111/codi.12403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim DW, Yoon HM, Park JS, Kim YH, Kang SB. Radiofrequency energy delivery to the anal canal: is it a promising new approach to the treatment of fecal incontinence? Am J Surg. 2009;197:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abbas MA, Tam MS, Chun LJ. Radiofrequency treatment for fecal incontinence: is it effective long-term? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:605–610. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182415406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maeda Y, Laurberg S, Norton C. Perianal injectable bulking agents as treatment for faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(5):CD007959. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007959.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tjandra JJ, Chan MK, Yeh HC. Injectable silicone biomaterial (PTQ) is more effective than carbon-coated beads (Durasphere) in treating passive faecal incontinence--a randomized trial. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:382–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Morris OJ, Smith S, Draganic B. Comparison of bulking agents in the treatment of fecal incontinence: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:517–523. doi: 10.1007/s10151-013-1000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maeda Y, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Pilot study of two new injectable bulking agents for the treatment of faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:268–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Graf W, Mellgren A, Matzel KE, Hull T, Johansson C, Bernstein M. Efficacy of dextranomer in stabilised hyaluronic acid for treatment of faecal incontinence: a randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:997–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Siproudhis L, Morcet J, Lainé F. Elastomer implants in faecal incontinence: a blind, randomized placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1125–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tjandra JJ, Lim JF, Hiscock R, Rajendra P. Injectable silicone biomaterial for fecal incontinence caused by internal anal sphincter dysfunction is effective. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:2138–2146. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0760-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brown SR, Wadhawan H, Nelson RL. Surgery for faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD001757. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001757.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rasmussen OO, Puggaard L, Christiansen J. Anal sphincter repair in patients with obstetric trauma: age affects outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:193–195. doi: 10.1007/BF02237126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tjandra JJ, Han WR, Goh J, Carey M, Dwyer P. Direct repair vs. overlapping sphincter repair: a randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:937–942; discussion 942-943. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6689-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Garcia V, Rogers RG, Kim SS, Hall RJ, Kammerer-Doak DN. Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter laceration: a randomized trial of two surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1697–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Young CJ, Mathur MN, Eyers AA, Solomon MJ. Successful overlapping anal sphincter repair: relationship to patient age, neuropathy, and colostomy formation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:344–349. doi: 10.1007/BF02237489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Engel AF, Kamm MA, Sultan AH, Bartram CI, Nicholls RJ. Anterior anal sphincter repair in patients with obstetric trauma. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1231–1234. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lamblin G, Bouvier P, Damon H, Chabert P, Moret S, Chene G, Mellier G. Long-term outcome after overlapping anterior anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1377–1383. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-2005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Glasgow SC, Lowry AC. Long-term outcomes of anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:482–490. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182468c22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Giordano P, Renzi A, Efron J, Gervaz P, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Previous sphincter repair does not affect the outcome of repeat repair. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:635–640. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thornton MJ, Kennedy ML, Lubowski DZ, King DW. Long-term follow-up of dynamic graciloplasty for faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:470–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Christiansen J, Sørensen M, Rasmussen OO. Gracilis muscle transposition for faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1039–1040. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kumar D, Hutchinson R, Grant E. Bilateral gracilis neosphincter construction for treatment of faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1645–1647. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800821219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wexner SD, Gonzalez-Padron A, Rius J, Teoh TA, Cheong DM, Nogueras JJ, Billotti VL, Weiss EG, Moon HK. Stimulated gracilis neosphincter operation. Initial experience, pitfalls, and complications. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:957–964. doi: 10.1007/BF02054681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mavrantonis C, Billotti VL, Wexner SD. Stimulated graciloplasty for treatment of intractable fecal incontinence: critical influence of the method of stimulation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:497–504. doi: 10.1007/BF02234176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Walega P, Romaniszyn M, Siarkiewicz B, Zelazny D. Dynamic versus Adynamic Graciloplasty in Treatment of End-Stage Fecal Incontinence: Is the Implantation of the Pacemaker Really Necessary? 12-Month Follow-Up in a Clinical, Physiological, and Functional Study. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:698516. doi: 10.1155/2015/698516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Devesa JM, Madrid JM, Gallego BR, Vicente E, Nuño J, Enríquez JM. Bilateral gluteoplasty for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:883–888. doi: 10.1007/BF02051193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Baeten CG, Bailey HR, Bakka A, Belliveau P, Berg E, Buie WD, Burnstein MJ, Christiansen J, Coller JA, Galandiuk S, et al. Safety and efficacy of dynamic graciloplasty for fecal incontinence: report of a prospective, multicenter trial. Dynamic Graciloplasty Therapy Study Group. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:743–751. doi: 10.1007/BF02238008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Matzel KE, Madoff RD, LaFontaine LJ, Baeten CG, Buie WD, Christiansen J, Wexner S. Complications of dynamic graciloplasty: incidence, management, and impact on outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1427–1435. doi: 10.1007/BF02234593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bresler L, Reibel N, Brunaud L, Sielezneff I, Rouanet P, Rullier E, Slim K. [Dynamic graciloplasty in the treatment of severe fecal incontinence. French multicentric retrospective study] Ann Chir. 2002;127:520–526. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3944(02)00828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rongen MJ, Uludag O, El Naggar K, Geerdes BP, Konsten J, Baeten CG. Long-term follow-up of dynamic graciloplasty for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:716–721. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Boyle DJ, Murphy J, Hotouras A, Allison ME, Williams NS, Chan CL. Electrically stimulated gracilis neosphincter for end-stage fecal incontinence: the long-term outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:215–222. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182a4b55f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wexner SD, Baeten C, Bailey R, Bakka A, Belin B, Belliveau P, Berg E, Buie WD, Burnstein M, Christiansen J, et al. Long-term efficacy of dynamic graciloplasty for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:809–818. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Christiansen J, Lorentzen M. Implantation of artificial sphincter for anal incontinence. Lancet. 1987;2:244–245. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90829-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hong KD, Dasilva G, Kalaskar SN, Chong Y, Wexner SD. Long-term outcomes of artificial bowel sphincter for fecal incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:718–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Altomare DF, Binda GA, Dodi G, La Torre F, Romano G, Rinaldi M, Melega E. Disappointing long-term results of the artificial anal sphincter for faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1352–1353. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Darnis B, Faucheron JL, Damon H, Barth X. Technical and functional results of the artificial bowel sphincter for treatment of severe fecal incontinence: is there any benefit for the patient? Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:505–510. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182809490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Van Koughnett JA, Wexner SD. Current management of fecal incontinence: choosing amongst treatment options to optimize outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:9216–9230. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i48.9216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Colquhoun P, Kaiser R, Efron J, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Vernava AM, Wexner SD. Is the quality of life better in patients with colostomy than patients with fecal incontience? World J Surg. 2006;30:1925–1928. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Norton C, Burch J, Kamm MA. Patients’ views of a colostomy for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1062–1069. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0868-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.O’Kelly TJ, Brading A, Mortensen NJ. In vitro response of the human anal canal longitudinal muscle layer to cholinergic and adrenergic stimulation: evidence of sphincter specialization. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1337–1341. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800801041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Simpson JA, Bush D, Gruss HJ, Jacobs A, Pediconi C, Scholefield JH. A randomised, controlled, crossover study to investigate the safety and response of 1R,2S-methoxamine hydrochloride (NRL001) on anal function in healthy volunteers. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16 Suppl 1:5–15. doi: 10.1111/codi.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bell D, Duffin A, Gruss HJ, Pediconi C, Jacobs A. A randomised, controlled, crossover study to investigate the pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics and safety of 1R,2S-methoxamine hydrochloride (NRL001) in healthy elderly subjects. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16 Suppl 1:27–35. doi: 10.1111/codi.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bell D, Duffin A, Jacobs A, Pediconi C, Gruss HJ. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, parallel-group, dose-escalating, repeat dose study in healthy volunteers to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacodynamic effects and pharmacokinetics of the once daily rectal application of NRL001 suppositories for 14 days. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16 Suppl 1:36–50. doi: 10.1111/codi.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gruss HJ, Pediconi C, Jacobs A. Meta-analysis for cardiovascular effects of NRL001 after rectal application in healthy volunteers. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16 Suppl 1:51–58. doi: 10.1111/codi.12545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Siproudhis L, Jones D, Shing RN, Walker D, Scholefield JH. Libertas: rationale and study design of a multicentre, Phase II, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled investigation to evaluate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of locally applied NRL001 in patients with faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16 Suppl 1:59–66. doi: 10.1111/codi.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kang SB, Lee HN, Lee JY, Park JS, Lee HS, Lee JY. Sphincter contractility after muscle-derived stem cells autograft into the cryoinjured anal sphincters of rats. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1367–1373. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9360-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Saihara R, Komuro H, Urita Y, Hagiwara K, Kaneko M. Myoblast transplantation to defecation muscles in a rat model: a possible treatment strategy for fecal incontinence after the repair of imperforate anus. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:981–986. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Salcedo L, Mayorga M, Damaser M, Balog B, Butler R, Penn M, Zutshi M. Mesenchymal stem cells can improve anal pressures after anal sphincter injury. Stem Cell Res. 2013;10:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Salcedo L, Penn M, Damaser M, Balog B, Zutshi M. Functional outcome after anal sphincter injury and treatment with mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3:760–767. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Raghavan S, Miyasaka EA, Gilmont RR, Somara S, Teitelbaum DH, Bitar KN. Perianal implantation of bioengineered human internal anal sphincter constructs intrinsically innervated with human neural progenitor cells. Surgery. 2014;155:668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Frudinger A, Kölle D, Schwaiger W, Pfeifer J, Paede J, Halligan S. Muscle-derived cell injection to treat anal incontinence due to obstetric trauma: pilot study with 1 year follow-up. Gut. 2010;59:55–61. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.181347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Romaniszyn M, Rozwadowska N, Nowak M, Malcher A, Kolanowski T, Walega P, Richter P, Kurpisz M. Successful implantation of autologous muscle-derived stem cells in treatment of faecal incontinence due to external sphincter rupture. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:1035–1036. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1692-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lehur PA, McNevin S, Buntzen S, Mellgren AF, Laurberg S, Madoff RD. Magnetic anal sphincter augmentation for the treatment of fecal incontinence: a preliminary report from a feasibility study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1604–1610. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f5d5f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wong MT, Meurette G, Wyart V, Lehur PA. Does the magnetic anal sphincter device compare favourably with sacral nerve stimulation in the management of faecal incontinence? Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e323–e329. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Barussaud ML, Mantoo S, Wyart V, Meurette G, Lehur PA. The magnetic anal sphincter in faecal incontinence: is initial success sustained over time? Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1499–1503. doi: 10.1111/codi.12423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pakravan F, Helmes C. Magnetic anal sphincter augmentation in patients with severe fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:109–114. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ger R, Condrea H, Raskin N, Addei K. Preliminary report. The transposition of a living sphincter. J Surg Res. 1982;33:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(82)90010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Goldsmith HS, Steward E. Fecal continence after abdominoperineal resection using the pedicled pyloric valve--an experimental study. Clin Oncol. 1982;8:313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Erdogan E, Rode H, Hickman R, Cywes S. Transposition of the antropylorus for anal incontinence--an experimental model in the pig. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:795–800. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Centeno Neto AA, Veyrac M, Briand D, Spiliotis J, Saint-Aubert B, Joyeux H. Autotransplantation of the pylorus sphincter at the terminal abdominal colostomy. Experimental study in dogs. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:874–879. doi: 10.1007/BF02049700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Goldsmith HS, Chandra A. Pyloric valve transposition as substitute for a colostomy in humans: a preliminary report. Am J Surg. 2011;202:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Chandra A, Kumar A, Noushif M, Gupta V, Singh D, Kumar M, Srivastava RN, Ghoshal UC. Perineal antropylorus transposition for end-stage fecal incontinence in humans: initial outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:360–366. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31827571ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Chandra A, Malhotra HS, M N, Gupta V, Singh SK, Kumar N, Lalla RS, Chandra A, Garg RK. Neuromodulation of perineally transposed antropylorus with pudendal nerve anastomosis following total anorectal reconstruction in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:1342–1348. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chandra A, Mishra B, Kumar S, Gupta V, Noushif M, Ghoshal UC, Misra A, Srivastava PK. Dynamic article: composite antropyloric valve and gracilis muscle transposition for total anorectal reconstruction: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:508–516. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Bridoux V, Gourcerol G, Kianifard B, Touchais JY, Ducrotte P, Leroi AM, Michot F, Tuech JJ. Botulinum A toxin as a treatment for overactive rectum with associated faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:342–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Richter HE, Matthews CA, Muir T, Takase-Sanchez MM, Hale DS, Van Drie D, Varma MG. A vaginal bowel-control system for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:540–547. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Scaglia M, Delaini G, Destefano I, Hultén L. Fecal incontinence treated with acupuncture--a pilot study. Auton Neurosci. 2009;145:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]