Abstract

Aim:

To determine the rural–urban differences in primary care practice, hospital inpatient care and total services.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study used data from Zenica-Doboj Canton in Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH). The overall sample size for the study was 1,995. Individual interviews were conducted in one randomly selected day of the week, except Monday and Friday, on the basis of EUROPEP (European Task Force on Patient Evaluations of General Practice Care) standardized questionnaire.

Results:

Out of total number (n=1 995), 47.9% was urban population and median of age was 42 years for both populations. The most of urban residents (81.4%) had finished high school or higher education compared with rural residents (58.5%) (p < 0.001). There are significant differences in employment status between rural and urban population (p < 0.001). Rural residents are more likely to travel more than 15 minutes to see their health facilities compared with urban residents (61.7% vs. 24.4%, respectively). Median of distance (kilometers) from residence location to the nearest hospital was statistically significantly higher in rural Me = 8.0 (5.0 do 14.5) km compared to urban population Me = 1.5 (1.0 to 3.0) km (p < 0.001). The rural population was more likely to buy drugs for medical treatment (p < 0.001) and parenteral injections in primary care practice (p < 0.001).

Conclusion:

There are significant differences in the overall health care assessment of rural populations as compared to urban populations.

Keywords: health care system, rural-urban population

1. INTRODUCTION

The one of the principal reforms of health system in Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) is focused on strengthening of primary health care and rationalization of hospital care (1). In spite of numerous criteria on how to differ rural or urban areas, studies worldwide refer to differences in health, as well as health care resources in rural areas in comparison to urban ones (2). Rural uninsured rates are higher than urban (3) and the uninsured often have difficulty obtaining needed care (4). The factors with the clearest relationship to satisfaction with health care system include the accessibility of medical care, the organizational structure of clinics, treatment length, perceived competence of physicians, clarity and retention of physicians' communication to patients, physicians’ affiliative behavior, physicians’ control and patients’ expectations (5). Population of rural U.S. counties has higher likelihood to yield poor health outcomes in accordance to measurements being encompassed within the County Health Rankings' indexed domains of health quality. Clinical care research refers to scarcity of resources available to rural population. There is strong evidence that rural population has a higher percentage of acute and chronic conditions treated within hospital facilities, but could have been prevented within primary health care (2). There are no reliable data dealing with the rural – urban differences within health care system in FBiH, and we aimed our study to determine the rural-urban differences in primary care practice, hospital inpatient care and total services in one canton in FBiH.

2. METHOD

A cross-sectional study was conducted and included all 12 municipalities of Zenica-Doboj Canton. A stratified sample of 146 primary health care practices was recruited. The achieved number of patients was 1,995 (14 per practice). Out of total number (n=1 995), 47.9% was urban population and median of age was 42 years for both populations. The study included patients with recent experience in general practice, aged 18 years or older. Individual interviews were conducted in one randomly selected day of the week, except Monday and Friday. The questionnaire was made on the basis of EUROPEP standardized questionnaire, related to the patient satisfaction with a health care (6, 7, 8). A patient satisfaction was rated on a 5 point scale, response categories being poor, fair, good, very good, and excellent. Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS version 21.0 for Windows system (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or as median with interquartile range (IQR, 25th to75th percentiles) dependent on normality of variables distribution. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistic test with a Lilliefors significance level was used for testing normality of distribution. In the case of categorical variables, counts and percentages were reported.

3. RESULTS

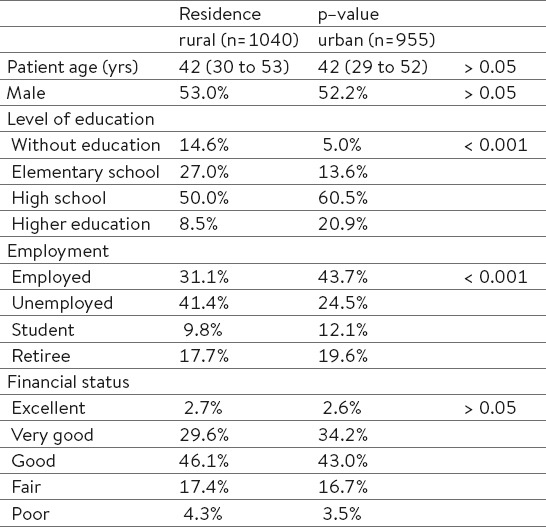

The most of urban residents (81.4%) had finished high school or higher education compared to rural residents (58.5%) (p < 0.001). There are significant differences in employment status between rural and urban population (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics rural and urban population

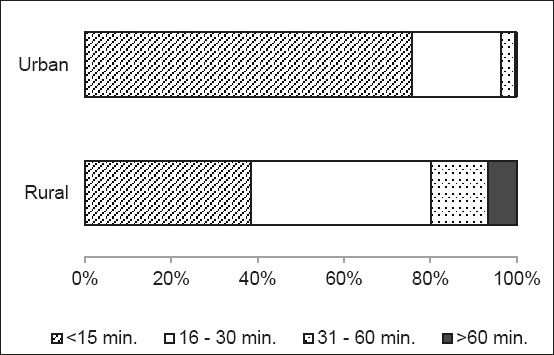

As Figure 1 demonstrates, rural residents are more likely to travel more than 15 minutes to see their health facilities compared to urban residents (61.7% vs. 24.4%, respectively). Median of distance (kilometers) from residence location to the nearest hospital was statistically significantly higher in rural (Me = 8.0; IQR= 5.0 do 14.5) km compared to urban population (Me = 1.5; IQR = 1.0 to 3.0) km (p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rural – urban differences in time (minutes) needed to reach health facilities (p < 0.001)

Rural residents are more likely to use public transport (26.0% vs. 3.0%), taxi service (9.2% vs. 4.0%) but not walking (23.4% vs. 51.1%) to reach health facilities, compared to urban residents, respectively (p < 0.001). Our results indicate that every fourth patient in rural (25.1%) and urban population (23.2%) waits for admission in doctor’s office less than 15 minutes, for 30.1% of rural and 26.0% of urban population the waiting time is more than an hour. There was not statistically significant differences in waiting time for admission in doctor’s office in primary health care between rural and urban population (p = 0.487).

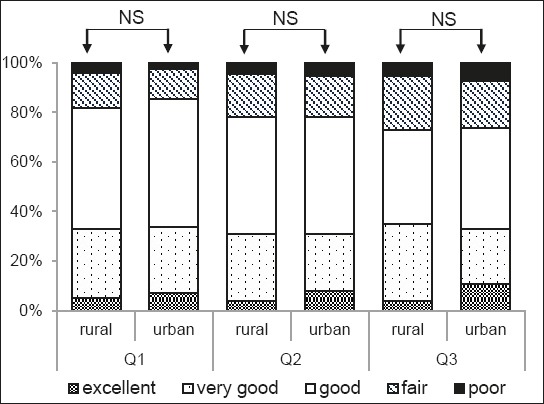

There was not a statistically significant association between residence in overall satisfaction proceedings of hospital staff in dealing with the patient (p = 0.144), professional conduct of hospital staff at admission (p = 0.790) and professional conduct during the hospital stay (p= 0. 805). (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Rural – urban differences in patient´s satisfaction with: Q1- proceedings of hospital staff in dealing with the patient; Q2–professional conduct of hospital staff at admission; Q3–professional conduct during the hospital stay (NS p > 0.05).

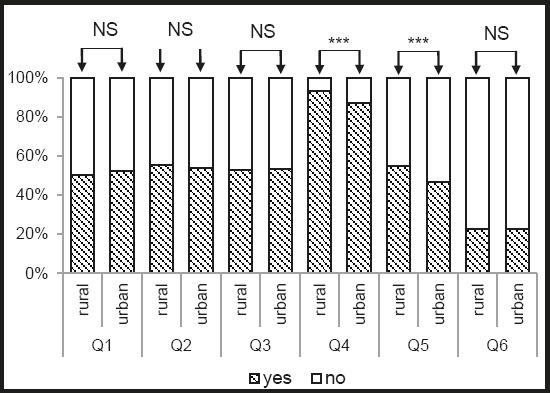

Rural residents are more likely to buy drugs for medical treatment (93.4% vs. 87.2%; χ²=21,940; df=1; p<0,001) and parenteral injections in primary care practice compared to urban residents (54.8% vs. 46.6%, respectively; χ²=12,976; df=1; p<0,001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Rural – urban differences in health care system: Q1- they visited phyisican in the last month; Q2 – they have health problems in the past 12 months but they did not request medical treatment; Q3 – they be ordered for physical examination; Q4 – they bought drugs for medical treatment; Q5 – they bought parenteral injections in primary care practice; Q6 – they paid unoffically to someone from medical staff (NS p > 0.05; *** p < 0.001).

There was not a statistically significant association between residence and: visiting a physician in the last month (χ²=0.674; df=1; p=0.412); if they have health problems in the past 12 months but they did not request medical treatment (χ²=0.401; df=1; p=0.527); ordering for a physical examination (χ²=0.031; df=1; p=0.860), unofficial payments to someone from medical staff (χ²=0.002; df=1; p=0.968).

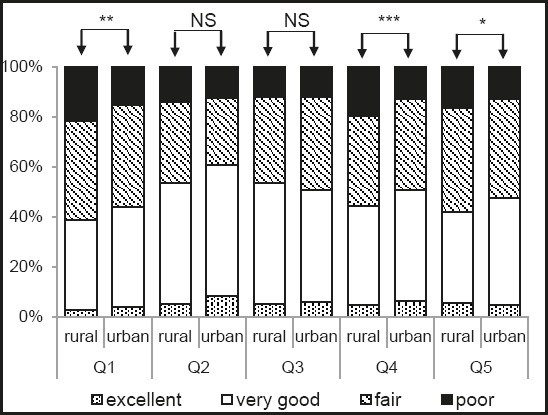

Urban residents are more satisfied with Primary Health Care Center (p = 0.001), Ambulatory Health Care (p < 0.001) and Specialist Services (p = 0.022) compared to rural residents (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Rural – urban differences in patient´s satisfaction with: Q1- Primary Health Care Center; Q2 – The General Hospital in Tesanj; Q3 – The Cantonal Hospital in Zenica; Q4 – Ambulatory Health Care; Q5 – Specialist Services (NS p > 0.05; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

4. DISCUSSION

This study compared urban and rural populations in Zenica-Doboj Canton in FBiH about Health Care Quality Assessment. Rural residents in Zenica-Doboj Canton usually travel long distance from the village to Ambulatory Health Care or higher level hospitals to deal with complicated situations and to receive better services. The study of Timothy J. Anderson et al., argued that residents living in rural U.S. counties have statistically significantly (p ≤ 0.05) lower scores in such areas as health behavior, morbidity factors, clinical care, and the physical environment (2). In our study, rural residents are more likely to use public transport and cab service to reach health facilities, and more likely to buy drugs for medical treatment and parenteral injections in primary care practice which suggests that rural populations spent more on travelling and medication. In the study of Farmer J et al., Satisfaction with local doctors and hospital services was higher in rural locations (9). In the study of Zhihua Yan et al, rural patients were generally more satisfied with healthcare service compared to urban and suburban residents, also (10). In our study, urban residents are more satisfied with Primary Health Care Center, Ambulatory Health Care and Specialist Services compared to rural residents. These findings could be explained by that urban population have a grater possibility of health care professionals’ choice.

5. CONCLUSION

Our results indicate that there are significant differences in the overall health care assessment of rural populations compared to urban populations. We would like to point out that health care policy decision makers in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina have to take into account all these differences in order to address the health inequalities between urban and rural areas of the country. Our results cannot be representative for the planning of public health policy but can certainly point out to weaknesses of health system and contribute its reform in FBiH.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: NONE DECLARED.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spasojevic N, Hrabac B, Huseinagic S. Patient’s Satisfaction with Health Care: a Questionnaire Study of Different Aspects of Care. Mater Sociomed. 2015;27(4):220–224. doi: 10.5455/msm.2015.27.220-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson TJ, Saman DM, Lipsky MS, Nawal Lutfiyya M. A cross-sectional study on health differences between rural and non-rural U.S. counties using the County Health Rankings. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:441. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1053-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenardson JD, Ziller EC, Coburn AF, Anderson N. Profile of Rural Health Insurance Coverage: A Chartbook. Portland, ME: University of Southern Maine, Muskie School of Public Service, Maine Rural Health Research Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg JA, Zaslavsky AM. Unmet Health Needs of Uninsured Adults in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284:2061–2069. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lochman JE. Factors related to patients’ satisfaction with their medical care. Journal of Community Health. 1983;9(2):91–109. doi: 10.1007/BF01349873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, Heje HN. Data quality and confirmatory factor analysis of the Danish EUROPEP questionnaire on patient evaluation of general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2008;26:174–180. doi: 10.1080/02813430802294803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjertnaes OA, Lyngstad I, Malterud K, Garratt A. The Norwegian EUROPEP questionnaire for patient evaluation of general practice: data quality, reliability and construct validity. Fam Pract. 2011;28:342–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandao AL, Giovanella L, Campos CE. Evaluation of primary care from the perspective of users: adaptation of the EUROPEP instrument for major Brazilian urban centers. Cien Saude Colet. 2013;18:103–14. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232013000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farmer J, Hinds K, Richards H, Godden D. Urban versus rural populations’ views of health care in Scotland. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005 Oct;10(4):212–19. doi: 10.1258/135581905774414240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan Z, Wan D, Li L. Patient satisfaction in two Chinese provinces: rural and urban differences. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2011;23(4):384–9. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]