Abstract

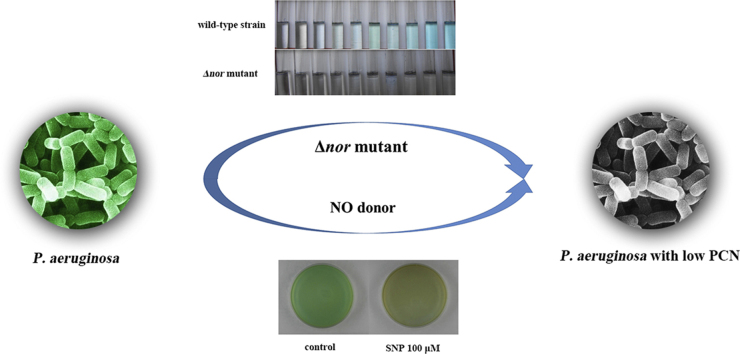

Pyocyanin (PCN), a virulence factor synthesized by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, plays an important role during clinical infections. There is no study of the effect of nitric oxide (NO) on PCN biosynthesis. Here, the effect of NO on PCN levels in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAO1, a common reference strain, was tested. The results showed that the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) can significantly reduce PCN levels (82.5% reduction at 60 μM SNP). Furthermore, the effect of endogenous NO on PCN was tested by constructing PAO1 nor (NO reductase gene) knockout mutants. Compared to the wild-type strain, the Δnor strain had a lower PCN (86% reduction in Δnor). To examine whether the results were universal with other P. aeruginosa strains, we collected 4 clinical strains from a hospital, tested their PCN levels after SNP treatment, and obtained similar results, i.e., PCN biosynthesis was inhibited by NO. These results suggest that NO treatment may be a new strategy to inhibit PCN biosynthesis and could provide novel insights into eliminating P. aeruginosa virulence as a clinical goal.

Keywords: Nitric oxide, PCN biosynthesis, Nitric oxide reductase, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Cystic fibrosis

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

NO can significantly reduce PCN production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

-

•

NOR knockout mutants effectively inhibit the synthesis of PCN in P. aeruginosa.

-

•

NO can also significantly reduce PCN production in clinical strains.

1. Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative bacillus that is rapidly becoming one of the major causes of opportunistic and nosocomial infections. Nosocomial infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa have become a worldwide problem. P. aeruginosa infections are associated with increased mortality and morbidity, particularly in susceptible patients with compromised immune systems and cystic fibrosis (CF); over 80% of CF patients die from these infections [1]. P. aeruginosa is naturally resistant to a large range of antibiotics (cephalosporins, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides) and may demonstrate additional resistance after unsuccessful treatment [2]. Some new strategies have been developed because of unsatisfactory traditional antibiotic treatment, including inhibition of the pathogenic factors of P. aeruginosa [3].

The main pathogenic factors of P. aeruginosa include elastase, alkaline protease, LasA protease, hemolysin, rhamnolipids and pyocyanin (5-methyl-1-hydroxyphenazine) (PCN) [4]. PCN, a blue colored phenazine exotoxin, can easily penetrate biological membranes and is found in the sputum of CF patients infected by P. aeruginosa [5]. Recent in vivo studies on alternative model hosts [6] and mice [7] have revealed that PCN is a key compound in P. aeruginosa infections and is a significant contributor to lung destruction during chronic P. aeruginosa infection in patients with bronchiectasis. PCN inhibits the ciliary beating of airway epithelial cells and enhances superoxide production [8].

Nitric oxide (NO) not only is important as a biological messenger but also has many biological effects [9]. Excessive exogenous NO can damage proteins, nucleic acids, and cellular membranes when the concentration of NO exceeds the capacity of cell metabolism. Nitric oxide reductase (NOR) is a common respiratory enzyme in eukaryotic cells and bacteria [10] that catalyzes the endogenous NO to N2O. The enzyme is involved in the denitrification pathway of P. aeruginosa by dissimilatory nitrate respiration [11]. If NO is not reduced by NOR to N2O, it may accumulate, and its toxicity could compromise bacteria. Therefore, the respiratory enzyme NOR is also a detoxifying enzyme. In other words, the enzyme is involved in the defense against exogenous NO in their surrounding natural habitats and within their hosts [12]. This enzyme is part of a cytochrome bc-type complex in P. aeruginosa. The norC and norB genes, encoding the cytochrome c and cytochrome b subunits, respectively, are clustered with the norD gene, which is required for the expression of the active NOR enzyme [13].

Recent research has shown that a high concentration of NO can inhibit the growth of E. coli [14]; however, sublethal concentrations of NO plays a great role in P. aeruginosa biofilm dispersal and helps in the biofilm mode of growth transition to the free-swimming planktonic state [15]. Is there any other effect of NO on P. aeruginosa? Based on this question, we tested the PCN biosynthesis of P. aeruginosa in the presence of different concentrations of the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP). Both SNP and nor gene knockout mutants could effectively inhibit the synthesis of PCN in P. aeruginosa.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Bacterial isolates

Four clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa were collected from Shanxi Province People’s Hospital in China (Table 1). The P. aeruginosa strains were isolated from urine (1) and sputum (3) samples. We also used the reference PAO1 strain as the main lab strain. The PAO1 strain was kindly provided by Professor Kangmin Duan (Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Manitoba, Canada).

Table 1.

List of strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | F- mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC), Φ 80 lacZ ΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara,leu) 7697 galU galK λ- rpsL nupG tonA | Invitrogen |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type, lab strain | This study |

| PAN1 | nor insertion mutant, GmR | This study |

| PA515 | Wild type, clinical strain | Clinic |

| PAN515 | nor insertion mutant, GmR | This study |

| PA196 | Wild type, clinical strain | Clinic |

| PA554 | Wild type, clinical strain | Clinic |

| PA914 | Wild type, clinical strain | Clinic |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEX18Amp | oriT+sacB+ gene replacement vector with multiple-cloning site from pUC18, AmpR | [18] |

| pHpΏ45 | Smr/Spcr gene from the R100.1 plasmid, transcription-termination sequences from pMJK4-18 plasmid, SmR/SpcR | [28] |

| pZ1918Gm | Source plasmid of Gmr cassette, GmR | [29] |

| pRK2013 | Broad-host-range helper vector, KanR | [19] |

| pEXB | pEX18Amp containing a nor fragment, AmpR | This study |

| pEXB1lacZ | pEXB1 containing Gmr-lacZ fragment from pZ1918Gm insert in the SphI site, AmpR/GmR | This study |

Antibiotic resistance markers: AmpR ampicillin, GmR gentamicin, KanR kanamycin.

2.2. Growth test

A 10 ml overnight culture of PAO1 was grown in LB medium (10% peptone, 5% yeast extract and 10% NaCl) at 37 °C on an orbital shaker at 200 rpm. The OD600 nm was adjusted to 0.1 using sterile LB and vortexed. Then, 100 μl was added to culture tubes containing 50 ml of LB medium. Next, sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was added to the LB in the tubes at the desired concentrations. For the untreated control, no SNP was added. The cultures were grown aerobically at room temperature on an orbital shaker at 200 rpm for 18–22 h. The growth was followed by measurement at OD600 nm every 2 h.

2.3. DNA manipulations

Chromosomal and plasmid DNA extraction, purification, enzymatic digestion, DNA ligation, and transformation of Escherichia coli were performed according to standard methods [16]. PCR was conducted using Taq polymerase (TaKaRa Japan) on an ABI PCR system. The following PCR program was used: 5 min at 95 °C and 30 cycles of 30 seconds at 95 °C, 30 seconds at annealing temperature (5 °C below the melting point), and 1 to 3.5 min (according to the size of the fragments) at 72 °C; 10 min at 72 °C; and then storage at 4 °C. The nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences were analyzed using DNASTAR and compared with the GenBank database using BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

2.4. Construction of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA515 nor gene knockout mutants

Protocols for DNA manipulation, cloning, reporter strain construction, and plasmid and chromosomal DNA purifications were obtained from Sambrook et al. [16]. Enzymes were purchased from either TaKaRa Japan or Promega USA. Two oligonucleotide primers were designed on the basis of the sequences flanking the nor genes of P. aeruginosa [17]. The nor genes of P. aeruginosa were amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA using the primer combinations NorEF (GTAGAATTCCTGGTCTACGTCCTGCAATGAG) and NorHR (GTGAAGCTTCCGATGAGGAACACCACCC). The amplified fragments were subsequently cloned into pMD18-T (TaKaRa) and sequenced. To avoid errors introduced by PCR, the DNA inserts from three individual clones were sequenced and compared. The nor genes consensus sequences from P. aeruginosa were compared to the nitric oxide reductase genes available in the GenBank database. For construction of the gene knockout mutants, a SacB-based strategy was employed [18]. The PCR product of the nor gene was digested with EcoRI and HindIII (site underlined in the primer sequences) and cloned into pEX18Amp. To construct the nor mutant, the DNA fragment containing the Gmr-lacZ from pZ1918Gm was inserted into the target genes. The final plasmid, named pEXB1lacZ, was verified by PCR and enzyme digestion. pEXBlacZ was introduced into P. aeruginosa by triparental mating [19], and nor was disrupted by integration of pEXBlacZ into the chromosome. The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1.

2.5. PCN assay

P. aeruginosa was inoculated into 1 L of LB medium and incubated at 37 °C in a shaking incubator at 150 rpm. The blue-colored broth (due to the presence of PCN) was transferred into 50-ml Oakridge tubes and centrifuged at 10,000g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a separating funnel and mixed with chloroform in a 1:1.5 (supernatant: chloroform) ratio. This mixture was shaken well and maintained undisturbed for 5–10 min to extract the PCN into the chloroform. The blue colored chloroform layer with PCN formed below the aqueous layer in the separating funnel was collected in a conical flask protected from light to prevent oxidation. This chloroform fraction was then transferred to a 500-mL vacuum rotary flask and concentrated in a vacuum rotary evaporator at 40 °C. The vacuum concentrated PCN fraction was purified using a silica gel column 3 cm in diameter and 60 cm in length. The column was packed with silica (mesh size 100–200) and equilibrated using a methanol-chloroform solvent system at a ratio of 1:1, and the concentrated PCN fraction was loaded onto the column. Methanol:chloroform (1:1) was used as the mobile phase to separate the PCN. The chloroform phase was then added to 0.2 N HCl (0.2 mL), which produced a pink to deep red color that is indicative of the presence of PCN [20]. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm, and the PCN concentrations were calculated.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The statistical significance for differences in this study was based on Student's two-tailed t-test. Differences were considered significant when the P-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of SNP on growth and PCN levels in P. aeruginosa

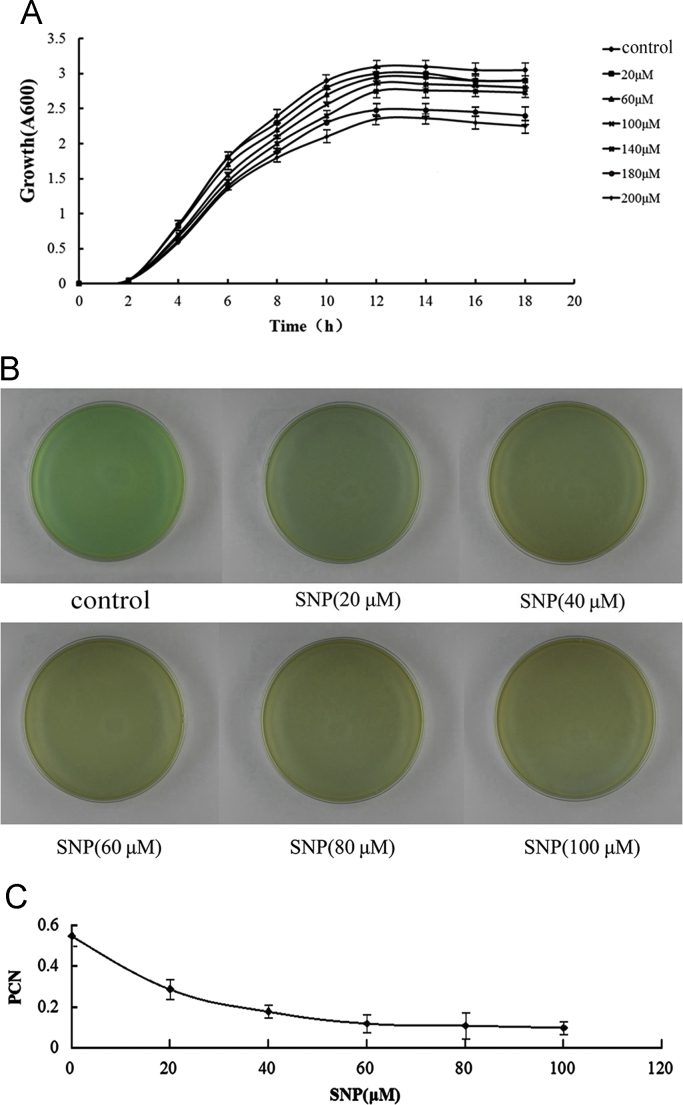

First, we tested the effect of the exogenous NO on growth. PAO1 was cultured in the presence of a range of concentrations (20, 60, 100, 140, 160 and 200 μM) of the NO donor SNP for the 18 h culture (Fig. 1A). Compared with the control (no SNP), the reduction rates for 20 μM, 60 μM, 100 μM, 140 μM, 160 μM, and 200 μM were 6.3%, 7.9%, 8.2%, 12.1%, 24.9%, and 25.8%, respectively. These results showed that the growth reduction was not strong at SNP concentrations below 100 μM. Then, we chose the SNP concentration below 100 μM for the PCN assay in which growth was not strongly inhibited. We measured PCN levels at a range of SNP concentrations (20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 μM). After the 18 h culture period, the reduction rates for 20 μM, 40 μM, 60 μM, 80 μM, and 100 μM were 45.4%, 65.1%, 82.5%, 83.1%, and 83.5%, respectively (Fig. 1B and C). The reduction ratios (PCN reduction:Growth reduction) were calculated, and the ratios for 20 μM, 60 μM, and 100 μM were 7.2, 10.5, and 9.7, respectively. From the results, we chose 60 μM SNP as the treatment condition in the subsequent tests because the maximum ratio was found at 60 μM SNP.

Fig. 1.

The effect of SNP on the growth and PCN of PAO1. (A) A growth test on PAO1: a liquid culture of PAO1 was grown in LB medium at 37 °C and at 200 rpm for 18 h. The NO donor compound in LB was added to the medium at the desired concentration. The OD600 values were determined every 2 h. (B) The PCN test on PAO1: the PAO1 were seeded onto LB agar and exposed to the indicated concentration of SNP. After 14 h, the samples were scanned for the color of the medium. (C) The PCN assay on PAO1: the medium was mixed with chloroform, and the chloroform phase was then added to 0.2 N HCl. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

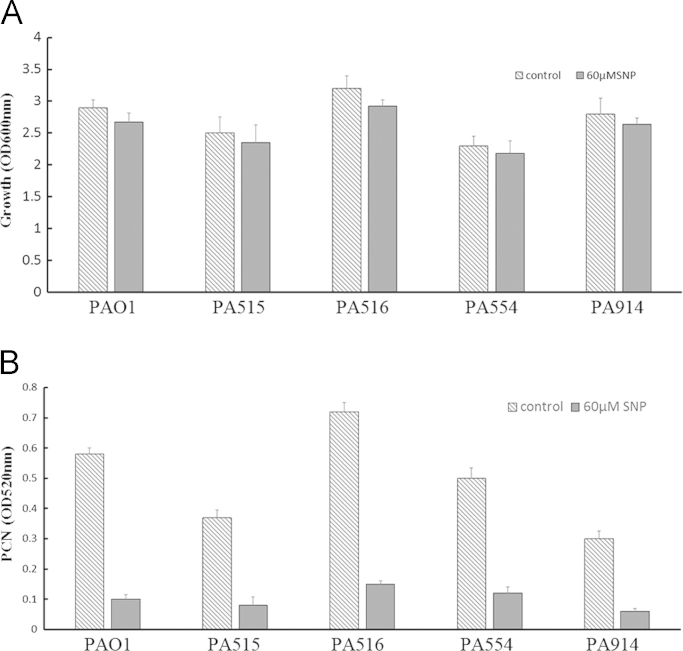

To examine whether the results were universal to other P. aeruginosa strains, four clinical strains were selected from Shaanxi Province People's Hospital (Table 2). The growth and PCN levels were examined. Similar to the results for PAO1 that showed 7.9% lower growth with 60 μM SNP after 18 h culture, the growth reduction rates in the 4 clinical strains were 6.1% for PA515, 8.8% for PA516, 5.2% for PA554, and 5.7% for PA914 (Fig. 2A). Similar to the results for PAO1 (82.5% reduction of PCN), the reduction of PCN in the 4 clinical strains exposed to 60 μM SNP for 18 h showed strong reductions in PCN levels (PCN reduction rate: 78.3% for PA515, 89.1% for PA516, 76.0% for PA554, and 70.8% for PA914) (Fig. 2B). The reduction ratios (PCN reduction:Growth reduction) were also calculated. The ratios were 10.5 for PAO1, 12.8 for PA515, 10.1 for PA516, 14.5 for PA554, and 12.4 for PA914.

Table 2.

List of clinical strains used in this study.

| Strain | Gender | Age | Source | Diagnose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA515 | Male | 63 | Sputum | Pulmonary infection, closed craniocerebral injury |

| PA516 | Male | 76 | Sputum | Aspiration pneumonia and coronary atherosclerotic heart disease, bottom wall myocardial infarction (mi), Parkinson’s disease, hyperplasia of prostate, neurogenic bladder, moderate anemia |

| PA554 | Male | 85 | Sputum | Cerebral infarction, lung infection repeatedly, carotid atherosclerosis, hypertension |

| PA914 | Male | 42 | Urine | Urinary tract infection, urinary bladder fistula, postoperative rectal cancer, postoperative left renal cyst, hyperplasia of prostate |

Fig. 2.

Growth and PCN reduction of clinical P. aeruginosa strains with 60 μM SNP. (A) A growth test on clinical P. aeruginosa strains: a liquid culture of clinical strains was grown in LB medium at 37 °C and at 200 rpm for 18 h. The 60 μM NO donor compound in LB was added to the medium. The OD600 values at 18 h were determined. (B) The PCN assay on clinical P. aeruginosa strains: the medium was mixed with chloroform, and the chloroform phase was then added to 0.2 N HCl. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm.

Compared with PAO1, the clinical strains had the same trend for PCN reduction with low, sublethal concentrations of NO. All of the data are presented as the mean±SD (n=4) and have been validated 4 times by experiments that had similar results.

3.2. Construction of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA515 nor gene knockout mutants

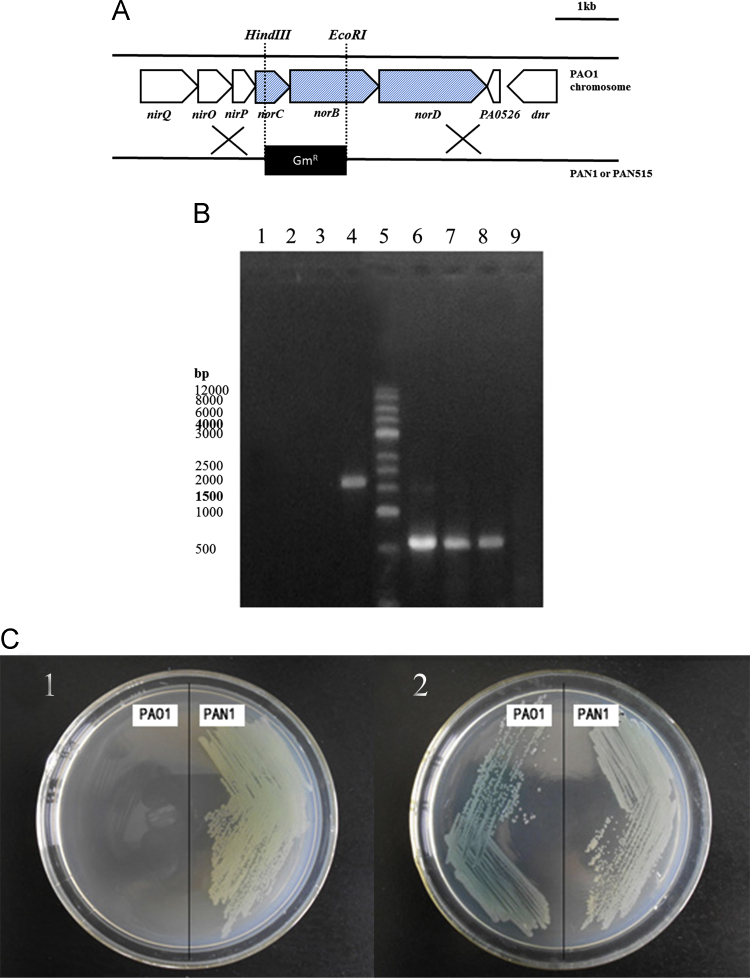

Based on the results for the exogenous NO, we tested the effect of endogenous NO on PCN levels in P. aeruginosa. Considering that the deletion of Nor lead to the accumulation of endogenous NO, the test was conducted by constructing nor mutants. First, to examine whether the nor gene were universal to P. aeruginosa strains, we analyzed the nor sequence in PAO1 and clinical strains by PCR and sequencing, and the results showed that these strains possessed the same nor gene sequences as PAO1. Considering the restriction sites and the plasmid available, we chose to delete the norBC gene. The gentamicin-resistance cassette was inserted into the norBC region by homologous recombination, which resulted in deletion of norB and norC. The restriction sites used for the construction are shown (Fig. 3A). Five gentamicin-resistant clones were analyzed by PCR (Fig. 3B). We designed 3 primers, including two end sequences of the target fragment, and a sequence in the replacement fragment. As shown in Fig. 3B, when PCR was conducted with the two ends primers, on the agarose gel only wild strains had the band, while the mutant strains and the plasmid had no bands; when using the primer in the replacement fragment for PCR, the result was reversed, and only mutant strains and the plasmid had the target band, and the wild strain did not. Then, we conducted a resistance test (Fig. 3C), and only the mutant strains carrying the resistance gene could grow in the resistance medium. Finally, we sequenced the insert fragment and confirmed that the norBC region was correctly replaced by Gm resistance gene in all of the clones. One of these clones was named PAN1 (nor mutant) and used for the subsequent experiments. To examine whether the results were universal for the other P. aeruginosa strains, we chose one of the clinical strains (PA515) to construct the nor mutant strain (PAN515) using the same procedure.

Fig. 3.

PCR and antibiotic resistance test. (A) A construction of the norBC mutant strain of P. aeruginosa. The gentamicin-resistance cassette was inserted into the norBC region by homologous recombination, which resulted in total deletion of norB and partial deletion of norC. The restriction sites used for the construction are shown. GmR, gentamicin resistance. (B) The PCR test: Lane 1: the PCR product of pEXB1lacZ using the NOREF/NORHR primer; Lane 2: the PCR product of PAN1 using the NOREF/NORHR primer; Lane 3: the PCR product of the PAN1 (parallel sample) strain using the NOREF/NORHR primer; Lane 4: the PCR product of PAO1 using the NOREF/NORHR primer; Lane 5: Marker; Lane 6: the PCR product of pEXB1lacZ using the lacZ-F/NORHR primer; Lane 7: the PCR product of PAN1 using the lacZ-F/NORHR primer; Lane 8: the PCR product of PAN1 (parallel sample) using the lacZ-F/NORHR primer; Lane 9: the PCR product of PAO1 using the lacZ-F/NORHR primer; (C) The antibiotic resistance test: (C1) growth of PAO1 and its disruption mutants on PIA medium containing Gm (only PAN1 could grow); and (C2) growth of PAO1 and its disruption mutants on PIA medium (no antibiotic was added, and all of the strains could grow well on it).

3.3. Effect of NOR enzyme deletions on the growth and PCN levels of P. aeruginosa

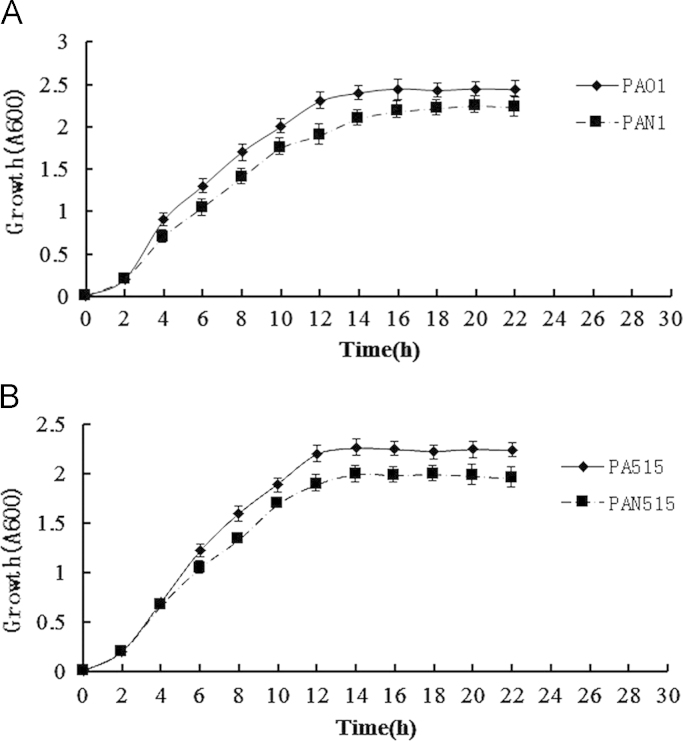

Based on the construction of the nor mutants, we first tested the growth of the PAO1 wild-type and nor mutants. The growth curves of the PAO1 wild-type and nor mutants for 22 h are shown in Fig. 4A. The difference in growth began at the exponential phase and was 14% at the end of this phase. In the stagnate phase, the difference decreased; the minimum difference was 6% at 18 h, and the maximum difference was 10% at 22 h. In the whole culture, the nor mutants grew slightly slower than the wild-type. The same growth test was carried out in PA515 wild-type and nor mutants (Fig. 4B). The difference in growth began at the exponential phase, which was 8% at the end of this phase. However, unlike PAO1, in the stagnate phase, the difference did not decrease, and the difference was maintained at approximately 8% until 22 h. From the results, it is clear that the nor gene did not have a strong effect on growth.

Fig. 4.

The effect of Nor on the growth of PAO1 and PA515. (A) The growth test for PAO1 and PAN1: liquid cultures of PAO1 and PAN1 were grown in LB medium at 37 °C and at 200 rpm for 22 h. OD600 values were determined every 2 h. (B) The growth test for PA515 and PAN515: liquid cultures of PA515 and PAN515 were grown in LB medium at 37 °C and at 200 rpm for 22 h. The OD600 values were determined every 2 h.

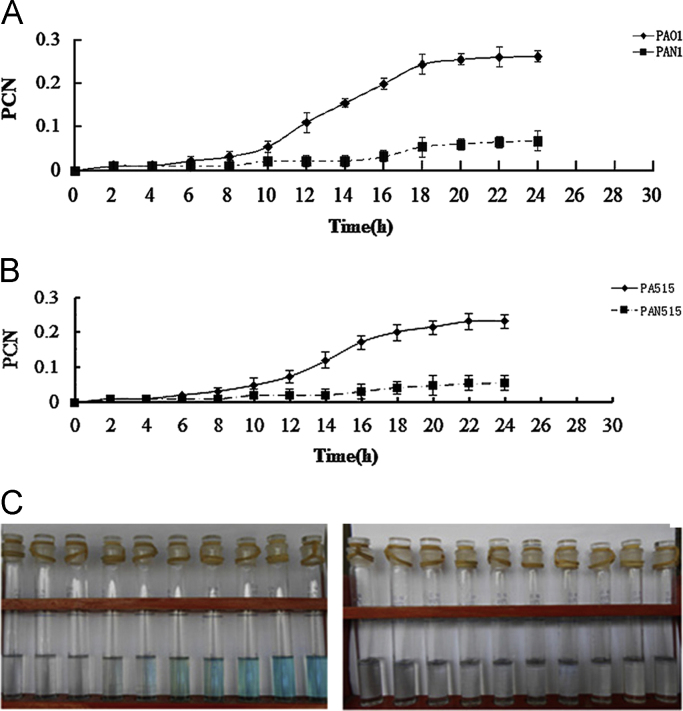

Then, we compared the levels of the PCN of PAO1 wild-type and nor mutants (Fig. 5A). After the 6 h culture, the two strains exhibited normal color with hardly any PCN. However, after 8 h, the PCN in the nor mutants was significantly lower than that in the wild-type. The PCN difference strictly increased until 18 h. After 18 h, the difference was maintained, and the maximum PCN reduction observed was 86% in PAN1 compared to PAO1 at 22 h (Fig. 5A). The same PCN test was conducted on PA515 wild-type and nor mutants. After a 6 h culture, the two strains exhibited normal color with hardly any PCN. After 8 h, the PCN in the nor mutants was significantly lower than that in the wild-type. However, unlike PAO1, the PCN difference strictly increased until 24 h. The observed PCN reduction was 85.2% in PAN515 compared to the PA515 at 22 h (Fig. 5B). The reduction ratio (PCN reduction: growth reduction) was also calculated. The ratios were 8.6 for PAN1 and 10.6 for PAN515.

Fig. 5.

The effect of Nor on the PCN produced by PAO1 and PA515. A. The PCN assay for PAO1 and PAN1: liquid cultures of PAO1 and PAN1 were grown in LB medium at 37 °C and at 200 rpm for 24 h. The medium was mixed with chloroform, and the chloroform phase was then added to 0.2 N HCl. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm. B. The PCN assay for PA515 and PAN515: liquid cultures of PA515 and PAN515 were grown in LB medium at 37 °C and at 200 rpm for 24 h. The medium was mixed with chloroform, and the chloroform phase was then added to 0.2 N HCl. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm. C: A picture of PCN in the chloroform layer (PAO1: left; PAN1: right). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The results show that the PCN biosynthesis weakened the NOR-deficient mutants when compared with wild-type strains. All of the data are presented as the mean±SD (n=4) and have been validated 4 times by experiments with similar results.

4. Discussion

PCN not only interferes with multiple cellular functions, it is also required in P. aeruginosa clinical infections, which can kill lung epithelial cells [7]. One of the strategies to overcome P. aeruginosa virulence is to inhibit PCN biosynthesis by antioxidant therapy that neutralizes PCN-generated oxidative stress [21]. Smith et al. presented a pathway in P. aeruginosa that is disrupted during anti-PCN therapy [22].

In this study, we investigated the effect of NO on PCN biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa. Unlike the minor effect on growth at a range of SNP concentrations (20–100 μM), the PCN biosynthesis was strongly inhibited with the increase in SNP. This trend was similar in PAO1 (the mode strain of P. aeruginosa) and 4 clinical strains (PCN reduction: 82.5% in PAO1, 78.3% in PA515, 89.1% in PA516, 76.0% in PA554, and 70.8% in PA914). Furthermore, we observed up to an 82.5% reduction in PCN biosynthesis with the 60 μM NO donor, whereas the reported reduction via other compounds was lower: 50% reduction with catechin (2–4 mM) [23], 56% with eugenol (at 50–400 μM) [24], and 76.5% with 2.5 g/L of Yunnan Baiyao, which is a well-known Chinese herbal medicine [25]. The results suggest that NO exerts better anti-virulence activity by interfering with PCN biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa.

In addition to the exogenous compound, some research shows that deleting certain genes can inhibit PCN biosynthesis. ΔBpiB09 (an NADP-dependent reductase) mutants reportedly produce up to 75% lower PCN than the wild-type after 16 h of growth [26]. In this study, we analyzed the effect of the nor gene, which coded the nitric oxide reductase, on PCN biosynthesis. Nitric oxide reductase is a key enzyme that catalyzes endogenous NO and reduces it to N2O. The deletion of nor will induce endogenous NO accumulation. We first analyzed the nor sequence in clinical strains (Table 2) by PCR and gene sequencing, and the results showed that these strains processed the same nor gene sequences, such as PAO1, which suggested that the nor sequence in P. aeruginosa is conservative. Then, the effects of endogenous NO on PCN in P. aeruginosa were tested by constructing NOR-deficient mutants. Our results showed that PCN biosynthesis was weakened in the NOR-deficient mutants (86% reduction in PAN1, 85.2% in PAN515) when compared with the wild-type strains. These results indicate that the accumulation of endogenous NO by deleting nor strongly inhibits PCN biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa.

In summary, both exogenous and endogenous NO can significantly reduce PCN production in P. aeruginosa as well as in clinical strains. These results suggest that we may use an NO donor or selective inhibition of NOR to eliminate P. aeruginosa virulence through inhibition of PCN biosynthesis. Further studies are required to determine the specific molecular mechanism involved. Previous studies have shown that NO participates in diverse biological processes [27]. It acts through redox-based modification of cysteine residue(s) of target proteins, called protein S-nitrosation. Seth et al. have demonstrated that S-nitrosylation of OxyR under anaerobic condition in E. coil can activate hcp transcription to protect against endogenous nitrosative stress [14]. PCN is synthesized through a series of complex steps including gene expression and modification from precursors into the tricyclic compound mediated by many key enzymes [3]. We have found that total protein S-nitrosation significantly increased when P. aeruginosa are exposed to NO (data not shown). We speculate that some proteins involving in PCN biosynthesis might be modified by NO, which is perhaps crucial to the PCN reduction. Further investigation is undergoing.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51278405, 31200094, 31225012, and 31030023), the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program: Grants 2011CB910900, 2012CB911000, and 2011CB503900), the Talent Introduction and Training Programs of Shaanxi Province Academy of Sciences (2015K-19), the Science and Technology Platform Programs of Shaanxi Province Academy of Sciences (2015K-33), and the National Laboratory of Biomacromolecules (2012kf01). We are grateful to Prof. Kangmin Duan (Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Manitoba, Canada) for kindly providing the gene-knockout system of Pseudomonas.

Contributor Information

Chang Chen, Email: changchen@moon.ibp.ac.cn.

Yi Wan, Email: wanyi6565@sina.com.

References

- 1.Goldberg J.B., Pier G.B. The role of the CFTR in susceptibility to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8(11):514–520. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01872-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dosler S., Karaaslan E. Inhibition and destruction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms by antibiotics and antimicrobial peptides. Peptides. 2014;62:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau G.W. The role of pyocyanin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Trends Mol. Med. 2004;10(12):599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyczak J.B., Cannon C.L., Pier G.B. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002;15(2):194–222. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.194-222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson R. Measurement of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazine pigments in sputum and assessment of their contribution to sputum sol toxicity for respiratory epithelium. Infect. Immun. 1988;56(9):2515–2517. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.9.2515-2517.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao H. A quorum sensing-associated virulence gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a LysR-like transcription regulator with a unique self-regulatory mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. A. 2001;98(25):14613–14618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251465298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau G.W. Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyocyanin is critical for lung infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 2004;72(7):4275–4278. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4275-4278.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ran H., Hassett D.J., Lau G.W. Human targets of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyocyanin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. A. 2003;100(24):14315–14320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2332354100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pekarova M. Novel insights into the electrochemical detection of nitric oxide in biological systems. Folia Biol. 2014;60(1):8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendriks J. Nitric oxide reductases in bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1459(2–3):266–273. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arai H., Igarashi Y., Kodama T. Expression of the nir and nor genes for denitrification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires a novel CRP/FNR-related transcriptional regulator, DNR, in addition to ANR. FEBS Lett. 1995;371(1):73–76. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00885-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busch A., Friedrich B., Cramm R. Characterization of the norB gene, encoding nitric oxide reductase, in the nondenitrifying cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68(2):668–672. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.2.668-672.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arai H., Iiyama K. Role of nitric oxide-detoxifying enzymes in the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa against the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2013;77(1):198–200. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seth D. Endogenous protein S-Nitrosylation in E. coli: regulation by OxyR. Science. 2012;336(6080):470–473. doi: 10.1126/science.1215643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barraud N. Involvement of nitric oxide in biofilm dispersal of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188(21):7344–7353. doi: 10.1128/JB.00779-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.J. Sambrook, E.F. Fritsch, T. Maniatis. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed., Gene cloning & DNA analysis an introduction, 1989

- 17.Stover C.K. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature. 2000;406(6799):959–964. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoang T.T. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene. 1998;212(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ditta G. Broad host range DNA cloning system for gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. A. 1980;77(12):7347–7351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cugini C. Farnesol, a common sesquiterpene, inhibits PQS production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65(4):896–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller M. Pyocyanin induces oxidative stress in human endothelial cells and modulates the glutathione redox cycle. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;33(11):1527–1533. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erickson D.L. Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing systems may control virulence factor expression in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect. Immun. 2002;70(4):1783–1790. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.1783-1790.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandeputte O.M. Identification of catechin as one of the flavonoids from Combretum albiflorum bark extract that reduces the production of quorum-sensing-controlled virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2010;76(1):243–253. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01059-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou L. Eugenol inhibits quorum sensing at sub-inhibitory concentrations. Biotechnol. Lett. 2013;35(4):631–637. doi: 10.1007/s10529-012-1126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao Z.G. An aqueous extract of Yunnan Baiyao inhibits the quorum-sensing-related virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Microbiol. 2013;51(2):207–212. doi: 10.1007/s12275-013-2595-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bijtenhoorn P. A novel metagenomic short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and virulence on Caenorhabditis elegans. Plos One. 2011;6(10):e26278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovacs I., Lindermayr C. Nitric oxide-based protein modification: formation and site-specificity of protein S-nitrosylation. Front. Plant Sci. 2013;4:137. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prentki P., Krisch H.M. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29(3):303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schweizer H.P. Two plasmids, X1918 and Z1918, for easy recovery of the xylE and lacZ reporter genes. Gene. 1993;134(1):89–91. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]