Abstract

Among patients with a preoperative positive axillary ultrasound, around 40% of them are pathologically proved to be free from axillary lymph node (ALN) metastasis. We aimed to develop and validate a model to predict the probability of ALN metastasis as a preoperative tool to support clinical decision-making. Clinicopathological features of 322 early breast cancer patients with positive axillary ultrasound findings were analyzed. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of ALN metastasis. A model was created from the logistic regression analysis, comprising lymph node transverse diameter, cortex thickness, hilum status, clinical tumour size, histological grade and estrogen receptor, and it was subsequently validated in another 234 patients. Coefficient of determination (R2) and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) were calculated to be 0.9375 and 0.864, showing good calibration and discrimination of the model, respectively. The false-negative rates of the model were 0% and 5.3% for the predicted probability cut-off points of 7.1% and 13.8%, respectively. This means that omission of axillary surgery may be safe for patients with a predictive probability of less than 13.8%. After further validation in clinical practice, this model may support increasingly limited surgical approaches to the axilla in breast cancer.

Axillary lymph node (ALN) status is one of the most important prognostic factors in patients with primary breast cancer and provides critical information for making treatment decisions1,2. Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is a standard surgical approach for all patients in the 20th century to both assess ALN status and treat metastatic ALNs. However, as many as about 70% of early breast cancer patients exhibit no ALN metastasis. In these cases, ALND can be deemed as a significant overtreatment with its accompanying morbidity such as pain, shoulder range of motion impairment, arm lymphedema, and paresthesia or numbness3,4,5,6.

During the past 15 years, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has been widely used as an alternative to ALND in clinically node negative patients. SLNB has improved the management of clinically ALN negative patients and reduced significantly morbidity. However, SLNB is an expensive and time-consuming procedure due to the need for pathological assessment of the SLN during the operation. Because of the significant risk of morbidity mentioned above and the disadvantages of SLNB, several randomized clinical trials were performed to assess if avoiding axillary surgery is safe in patients with low risk of ALN metastasis. The results from these studies showed similar disease free survival and overall survival in patients with ALND or without any axillary surgery7,8. Nowadays, indications for the management of ALND become much stricter due to the promising results from several randomized controlled clinical trials, such as the AMAROS trial9,10,11. These trials demonstrated that either axillary radiotherapy9 or omission of further axillary surgery10,11 could be a safe alternative to ALND in highly selected patients with limited sentinel lymph node (SLN) metastasis, without compromising overall survival, nor regional disease control, although one study showed that an estimated 11–27% of patients have residual nodal disease which was not removed by surgery10.

Based on the above findings, there remains considerable doubt about the value of the SLNB in selected patients. A randomized trial has been launched in Italy to evaluate whether the SLNB can be safely omitted in patients with clinically negative ALN12. The result of the trial is still to be expected. Seventy-five percent of patients have pathologically negative axillary nodes in those with preoperative negative ultrasound13. Meanwhile, among patients with a preoperative positive ultrasound, around 40% have negative axillary nodes upon final pathological examination of ALND specimen14. Therefore, it is of great clinical relevance to select those patients that can safely omit axillary surgery or should not undergo either a SLNB or an ALND.

Clearly, there is a need for the development of a decision-making tool in order to reliably select patients unlikely having ALN involvement. The aim of this study is to develop and validate a model to predict the probability of ALN metastasis in early breast cancer patients with positive axillary ultrasound, providing a preoperative tool for assisting clinical decision-making. We generated the model with a training cohort of 322 patients and validated it in an additional set of 234 patients from the same institution. A nomogram was created as a graphical representation of the model. In addition, a user-friendly web-based calculator was developed to facilitate use of the model in a clinical setting while providing complete insight in the model’s parameters.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients

The descriptive clinicopathological characteristics of patients in the modeling and validation group are provided in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups, except for P53, estrogen receptor (ER), and ALN variables including number of lymph nodes detected by ultrasound, transverse diameter, cortical thickness and absence of hilum.

Table 1. Comparison between modeling group and validation group by clinicopathological characteristics.

| Characteristic | Modeling No. (%) | Validation No. (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | 322 (100%) | 234 (100%) | - |

| Age at diagnosis (year) | 0.218 | ||

| <=35 | 25 (7.8%) | 12 (5.1%) | |

| >35 | 297 (92.2%) | 222(94.9%) | |

| Menopausal status | 0.155 | ||

| Premenopausal | 182 (56.5%) | 118 (50.4%) | |

| Postmenopausal | 140 (43.5%) | 116 (49.6%) | |

| Clinical Tumor size (mm) | 0.594 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 30 (23, 40) | 30 (24, 40) | |

| Clinical tumor size | 0.355 | ||

| T1 | 74 (23.0%) | 44(18.8%) | |

| T2 | 223 (69.3%) | 169(72.2%) | |

| T3 | 22 (6.8%) | 21(9.0%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.9%) | 0(0.0%) | |

| Tumor location | 0.457 | ||

| UOQ | 152 (47.2%) | 118(50.4%) | |

| LQQ | 42 (13.0%) | 25(10.7%) | |

| UIQ | 51 (15.8%) | 43(18.4%) | |

| LIQ | 15 (4.7%) | 14(6.0%) | |

| Central | 62 (19.3%) | 34(14.5%) | |

| Histological grade | 0.085 | ||

| I | 49 (15.2%) | 24(10.2%) | |

| II | 104 (32.3%) | 95(40.6%) | |

| III | 154 (47.8%) | 113(48.3%) | |

| Unknown | 15 (4.7%) | 2(0.9%) | |

| Histological type | 0.49 | ||

| Ductal | 294 (91.3%) | 220(94.0%) | |

| Lobular | 10 (3.1%) | 5(2.1%) | |

| Other | 18 (5.6%) | 9(3.9%) | |

| ER | 0.006 | ||

| Negative | 119 (37.0%) | 78(33.3%) | |

| 1+ | 22 (6.8%) | 25(10.7%) | |

| 2+ | 57 (17.7%) | 21(9.0%) | |

| 3+ | 124 (38.5%) | 110(47.0%) | |

| PR | 0.654 | ||

| Negative | 132 (41.0%) | 106(45.3%) | |

| 1+ | 38 (11.8%) | 30(12.8%) | |

| 2+ | 63 (19.6%) | 39(16.7%) | |

| 3+ | 89 (27.6%) | 59(25.2%) | |

| Her-2 | 0.336 | ||

| Negative | 223 (69.3%) | 153(65.4%) | |

| Positive | 99 (30.7%) | 81(34.6%) | |

| Ki-67 | 0.08 | ||

| <=14 | 51 (15.9%) | 25(10.7%) | |

| >14 | 268 (83.2%) | 207(88.5%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.9%) | 2(0.8%) | |

| P53 | <0.001 | ||

| Negative | 117 (36.3%) | 38(16.2%) | |

| Positive | 197 (61.2%) | 191(81.6%) | |

| Unknown | 8 (2.5%) | 5(2.2%) | |

| VEGF-C | 0.231 | ||

| Negative | 75 (23.3%) | 43(18.4%) | |

| Positive | 222 (68.9%) | 165(70.5%) | |

| Unknown | 25 (7.8%) | 26(11.1%) | |

| Molecular subtype | 0.622 | ||

| Luminal A | 173 (53.7%) | 119(50.9%) | |

| Luminal B | 44 (13.7%) | 38(16.2%) | |

| HER-2 enriched | 51 (15.8%) | 43(18.4%) | |

| Triple negative | 54 (16.8%) | 34(14.5%) | |

| Lymph node detected by ultrasound Number | 0.025 | ||

| 1 | 123 (38.2%) | 68(29.1%) | |

| >=2 | 199 (61.8%) | 166(70.9%) | |

| Transverse diameter (mm) | 0.005 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 13 (10, 17) | 15 (11, 18) | |

| Longitudinal diameter (mm) | 0.092 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (5, 9) | 7 (5.75, 10) | |

| Longitudinal to transverse ratio | 0.441 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.53 (0.44, 0.67) | 0.53 (0.42, 0.67) | |

| Cortical thickness (mm) | 0.029 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 4 (3, 6) | 4 (3, 7) | |

| Absence of medulla | 0.522 | ||

| Yes | 87 (27.0%) | 69(29.5%) | |

| No | 235 (73.0%) | 165(70.5%) | |

| Absence of hilum | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 126 (39.1%) | 128(54.7%) | |

| No | 196 (60.9%) | 106(45.3%) | |

| Lymph node metastases | 0.147 | ||

| Yes | 163 (50.6%) | 133(56.8%) | |

| No | 159 (49.4%) | 101(43.2%) |

UOQ: upper outer quadrant; UIQ: upper inner quadrant; LOQ: lower outer quadrant;

LIQ: lower inner quadrant; IQR: Interquartile range, which is the 25th percentile, 75th percentile.

197 patients (61.2%) positively expressed P53 in the modeling group, compared with 191 patients (81.6%) in the validation group. With regard to ER, the positive expression rate between the modeling group and validation group were quite similar, being 63% and 66.7%, respectively. However, the distribution of ER positive patients in the two groups were quite different, with a larger percentage of patients being ER 2+ in the modeling cohort (17.7%) compared to the validation cohort (9.0%), and with relatively smaller percentage in ER 1+ (6.8% versus 10.7%) and ER 3+ (38.5% versus 47.0%) in the modelling group. We considered that the difference might due to the relatively small number of patient population.

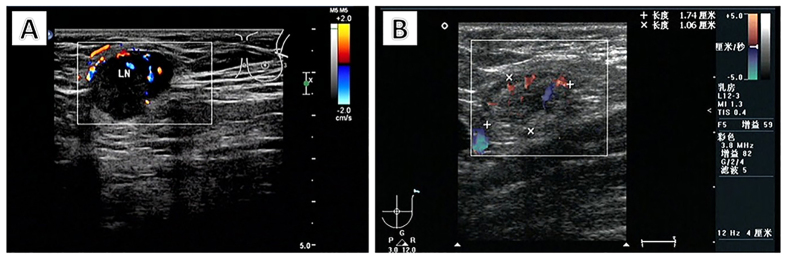

The absolute median number of transverse diameter and cortical thickness between the modeling group and the validation group matched closely, with 13 mm versus 15 mm, and both 4 mm, respectively. A total of 54.7% of patients lost their lymph node hilum in the validation group, compared with only 39.1% in the modeling group. More than one lymph node was found in 199 patients (61.8%) in the modeling group, compared with 166 patients (70.9%) in the validation group. Typical ultrasound findings of positive and negative lymph nodes are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Ultrasound findings of positive and negative axillary lymph nodes.

A positive lymph node (A) was detected in the left axilla with thickened cortex, and the hilum is disappeared. The diameters are 19 × 16 mm. A negative lymph node (B) was detected in the left axilla with normal cortex and hilum. The diameters of the lymph node are 21 × 6 mm.

Lymph node metastasis was detected in 163 patients (50.6%) in the modeling group, compared with 133 patients (56.8%) in the validation group. Results of comparison of lymph node metastasis by clinicopathological variables in the modeling group are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Comparison of axillary lymph nodes metastasis by clinicopathological variables.

| Characteristic | Axillary lymph node metastasis (n = 163) | No axillary lymph node metastasis (n = 159) | All patients (n = 322) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (year) | 0.785 | |||

| <=35 | 12 (48.0%) | 13 (52.0%) | 25 | |

| >35 | 151 (50.8%) | 146 (49.2%) | 297 | |

| Menopausal status | 0.632 | |||

| Premenopausal | 90 (49.5%) | 92 (50.5%) | 182 | |

| Postmenopausal | 73 (52.1%) | 67 (47.9%) | 140 | |

| Clinical tumor size (mm) | 0.007 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 30 (25, 40) | 30 (20, 40) | 30 (23, 40) | |

| Clinical tumor size | <0.001 | |||

| T1 | 23 (31.1%) | 51 (68.9%) | 74 | |

| T2 | 131 (58.7%) | 92 (41.3%) | 223 | |

| T3 | 7 (31.8%) | 15 (68.2%) | 22 | |

| Unknown | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 3 | |

| Tumor location | 0.626 | |||

| UOQ | 72 (47.4%) | 80 (52.6%) | 152 | |

| LOQ | 21 (50.0%) | 21 (50.0%) | 42 | |

| UIQ | 25 (49.0%) | 26 (51.0%) | 51 | |

| LIQ | 9 (60.0%) | 6 (40.0%) | 15 | |

| Center | 36 (58.1%) | 26 (41.9%) | 62 | |

| Histological grade | <0.001 | |||

| I | 10 (20.4%) | 39 (79.6%) | 49 | |

| II | 49 (47.1%) | 55 (52.9%) | 104 | |

| III | 101 (65.6%) | 53 (34.4%) | 154 | |

| Unknown | 3 (20.0%) | 12 (80.0%) | 15 | |

| Histological type | 0.318 | |||

| Ductal | 152 (51.7%) | 142 (48.3%) | 294 | |

| Lobular | 5 (50.0%) | 5 (50.0%) | 10 | |

| Other | 6 (33.3%) | 12 (66.7%) | 18 | |

| ER | 0.013 | |||

| Negative | 49 (41.2%) | 70 (58.8%) | 119 | |

| 1+ | 8 (36.4%) | 14 (63.6%) | 22 | |

| 2+ | 32 (56.1%) | 25 (43.9%) | 57 | |

| 3+ | 74 (59.7%) | 50 (40.3%) | 124 | |

| PR | 0.009 | |||

| Negative | 54 (40.9%) | 78 (59.1%) | 132 | |

| 1+ | 20 (52.6%) | 18 (47.4%) | 38 | |

| 2+ | 32 (50.8%) | 31 (49.2%) | 63 | |

| 3+ | 57 (64.0%) | 32 (36.0%) | 89 | |

| Her-2 | 0.788 | |||

| Negative | 114 (51.1%) | 109 (48.9%) | 223 | |

| Positive | 49 (49.5%) | 50 (50.5%) | 99 | |

| Ki-67 | 0.821 | |||

| <=14 | 25 (49.0%) | 26 (51.0%) | 51 | |

| >14 | 136 (50.7%) | 132 (49.3%) | 268 | |

| Unknown | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 3 | |

| P53 | 0.954 | |||

| Negative | 59 (50.4%) | 58 (49.6%) | 117 | |

| Positive | 100 (50.8%) | 97 (49.2%) | 197 | |

| Unknown | 4 (50.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 8 | |

| VEGF-C | 0.215 | |||

| Negative | 34 (45.3%) | 41 (54.7%) | 75 | |

| Positive | 119 (53.6%) | 103 (46.4%) | 222 | |

| Unknown | 10 (40.0%) | 15 (60.0%) | 25 | |

| Molecular subtype | 0.007 | |||

| Luminal A | 98 (56.7%) | 75 (43.3%) | 173 | |

| Luminal B | 26 (59.0%) | 18 (41.0%) | 44 | |

| HER-2 enriched | 17 (33.3%) | 34 (66.7%) | 51 | |

| Triple negative | 22 (40.7%) | 32 (59.3%) | 54 | |

| Lymph node detected by ultrasound Number | 0.010 | |||

| 1 | 51 (41.5%) | 72 (58.5%) | 123 | |

| >=2 | 112 (56.3%) | 87 (43.7%) | 199 | |

| Transverse diameter (mm) | 0.001 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 14 (10, 19) | 12 (9, 15) | 13 (10, 17) | |

| Longitudinal diameter (mm) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 8 (6, 10) | 6 (5, 7) | 7 (5, 9) | |

| Longitudinal to transverse ratio | 0.005 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0.57 (0.44, 0.71) | 0.50 (0.43, 0.60) | 0.53 (0.44, 0.67) | |

| Cortical thickness (mm) | <0.001 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (4, 9) | 3 (2, 4) | 4 (3, 6) | |

| Absence of medulla | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 73 (83.9%) | 14 (16.1%) | 87 | |

| No | 90 (38.3%) | 145 (61.7%) | 235 | |

| Absence of hilum | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 102 (81.0%) | 24 (19.0%) | 126 | |

| No | 61 (31.1%) | 135 (68.9%) | 196 |

UOQ, upper outer quadrant; UIQ, upper inner quadrant; LOQ, lower outer quadrant; LIQ, lower inner quadrant;

IQR, Interquartile range, which is the 25th percentile, 75th percentile.

Univariate and multivariate analyses in the modeling group

In the univariate analysis, factors that were significantly associated with ALN metastasis included clinicopathological variables of primary tumour including clinical tumour size (p = 0.037), histological grade (p < 0.001), ER (p = 0.002), progesterone receptor (PR) (p = 0.001), molecular subtype (p = 0.009), and lymph node variables assessed by ultrasonography including number of nodes (p = 0.010), transverse diameter (p < 0.001) and longitudinal diameter of lymph node (p < 0.001), longitudinal-to-transverse ratio (p = 0.001), cortical thickness (p < 0.001), absence of medulla (p < 0.001), and absence of hilum (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis for factors associated with axillary lymph node metastasis.

| Characteristic | Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | Coefficient | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Age at diagnosis (year) | |||||||

| <=35 | 1 | ||||||

| >35 | 1.120 | 0.495–2.536 | 0.785 | ||||

| Menopausal status | |||||||

| Premenopausal | 1 | ||||||

| Postmenopausal | 0.898 | 0.578–1.395 | 0.632 | ||||

| Clinical tumor size (mm) | 1.210 | 1.011–1.448 | 0.037 | 0.305 | 1.357 | 1.053–1.748 | 0.018 |

| Clinical tumor size | <0.001 | ||||||

| T1 | 1 | ||||||

| T2 | 3.157 | 1.804–5.527 | <0.001 | ||||

| T3 | 1.035 | 0.372–2.879 | 0.948 | ||||

| Tumor location | 0.629 | ||||||

| UOQ | 1 | ||||||

| LOQ | 0.65 | 0.358–1.180 | 0.157 | ||||

| UIQ | 0.722 | 0.329–1.588 | 0.418 | ||||

| LIQ | 1.083 | 0.343–3.420 | 0.891 | ||||

| Center | 0.694 | 0.329–1.464 | 0.338 | ||||

| Histological grade | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| I | 1 | 1 | |||||

| II | 3.475 | 1.570–7.689 | 0.002 | 1.502 | 4.492 | 1.644–12.271 | 0.003 |

| III | 7.432 | 3.441–16.054 | <0.001 | 2.09 | 8.083 | 3.022–21.616 | <0.001 |

| Histological type | 0.300 | ||||||

| Ductal | 1 | ||||||

| Lobular | 0.935 | 0.265–3.296 | 0.916 | ||||

| Other | 0.425 | 0.144–1.253 | 0.121 | ||||

| ER | 1.303 | 1.101–1.541 | 0.002 | 0.379 | 1.461 | 1.166–1.832 | 0.001 |

| PR | 1.338 | 1.121–1.597 | 0.001 | ||||

| Her-2 | 0.937 | 0.584–1.504 | 0.788 | ||||

| Ki-67 | |||||||

| <=14 | 1 | ||||||

| >14 | 1.072 | 0.589–1.950 | 0.821 | ||||

| P53 | 0.987 | 0.823–1.183 | 0.885 | ||||

| VEGF-C | 1.266 | 0.981–1.633 | 0.070 | ||||

| Molecular subtype | 0.009 | ||||||

| Luminal A | 1 | ||||||

| Luminal B | 1.105 | 0.565–2.165 | 0.77 | ||||

| HER-2 enriched | 0.383 | 0.199–0.737 | 0.004 | ||||

| Triple negative | 0.526 | 0.283–0.979 | 0.043 | ||||

| Lymph node detected by ultrasound Number | |||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||

| >=2 | 1.817 | 1.153–2.865 | 0.010 | ||||

| Transverse diameter (mm) | 1.08 | 1.034–1.127 | <0.001 | 0.063 | 1.065 | 1.002–1.132 | 0.044 |

| Longitudinal diameter (mm) | 1.351 | 1.213–1.505 | <0.001 | ||||

| Longitudinal-to-transverse ratio | 9.798 | 2.494–38.491 | 0.001 | ||||

| Cortical thickness (mm) | 1.653 | 1.451–1.883 | <0.001 | 0.277 | 1.319 | 1.106–1.571 | 0.002 |

| Absence of medulla | |||||||

| No | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 8.401 | 4.477–15.765 | <0.001 | ||||

| Absence of hilum | |||||||

| No | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 9.406 | 5.494–16.104 | <0.001 | 1.42 | 4.137 | 1.799–9.514 | 0.001 |

| Constant | −5.710 | ||||||

UOQ: upper outer quadrant; UIQ: upper inner quadrant; LOQ: lower outer quadrant; LIQ: lower inner quadrant;

IQR: Interquartile range, which is the 25th percentile, 75th percentile; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, transverse diameter (p = 0.044), cortical thickness (p = 0.002), absence of hilum (p = 0.001), clinical tumour size (p = 0.018), histological grade (p < 0.001), and ER (p = 0.001) were identified as independent predictors of ALN metastasis and were included in the predictive model. Histological grade III showcases the highest predictive value with an OR of 8.083, in comparison with grade I tumours (95% CI, 3.022-21.616) (Table 3).

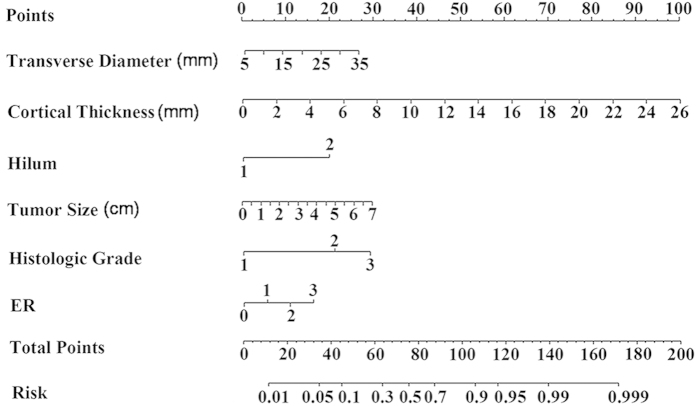

Predictive equation, nomogram and web-based calculator

An equation, ln (p/1 − p) = 0.063 × a + 0.277 × b + 1.420 × c + 1.502 × d1 + 2.090 × d2 + 0.305 × e + 0.379 × f − 5.710, was generated to evaluate the probability of ALN metastasis preoperatively based on the result from the multivariate logistic regression analysis in the modeling group.

The denotement of letters in the equation is as follows: p = the probability of ALN metastasis; a = transverse diameter of lymph node as detected by ultrasound in mm; b = cortical thickness of lymph node as detected by ultrasound in mm; c = hilum (0 if present, 1 if absent); d1 = histological grade 1 (0 if grade 1 (G1) or grade 3 (G3), 1 if grade (G2)); d2 = histological grade 2 (0 if G1 or G2, 1 if G3); e = clinical tumour size in cm; f = ER (0 if−, 1 if +, 2 if ++, 3 if +++).

A nomogram was developed based on the result of multivariate logistic regression analysis (Fig. 2). The nomogram comprises nine rows and representation of each row is as follows. The first row (Points) is the point assignment for each variable. For an individual patient, each variable is assigned a point value according to the clinicopathological characteristics by drawing a vertical line between the exact variable value and the Points line. Subsequently, a total point score (row 8) can be calculated by summing all of the assigned points for the six variables. The predictive probability of axillary metastasis can be obtained by drawing a vertical line between Total Points and Risk (the final row). In addition, a web-based calculator was developed to facilitate use of the model in a clinical setting. The web-based calculator is freely accessible at https://app.evidencio.com/models/show/170.

Figure 2. Nomogram for predicting the probability of axillary lymph node metastasis.

The nomogram comprises nine rows. The first row is the point assignment for each variable. For an individual patient, each variable is assigned a point value according to the clinicopathological characteristics by drawing a vertical line between the exact variable value and the Points line. Subsequently, a total point (row 8) can be obtained by summing all of the assigned points for the six variables. Finally, the predictive probability of axillary metastasis can be obtained by drawing a vertical line between Total Points and Risk (the final row).

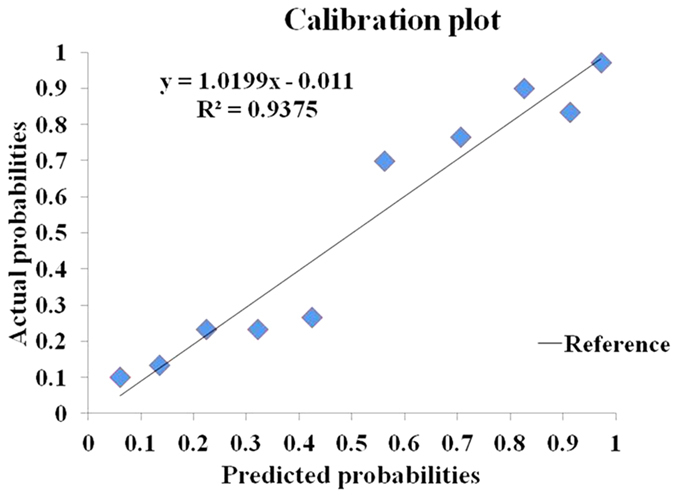

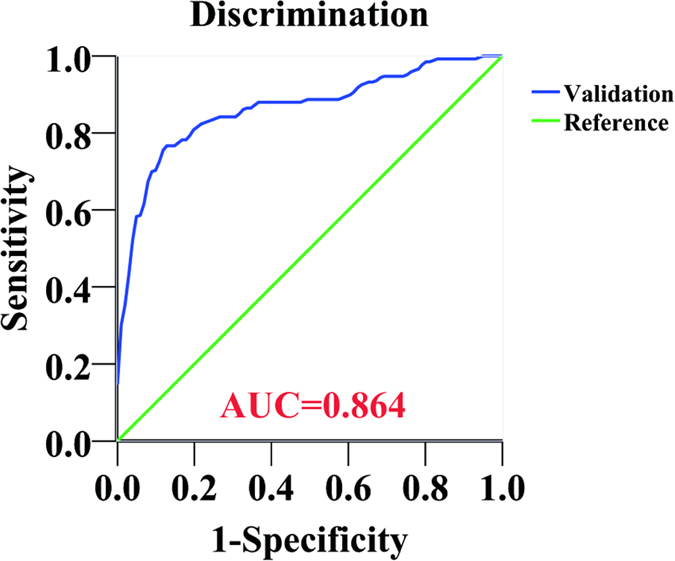

The mean predicted probability and mean actual rate of axillary metastasis in each decile were calculated. Calibration of the model was considered acceptable with R2 of 0.9375 (Fig. 3). The Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test resulted in a p value of 0.18, indicating that the model fits well. The model was then validated with an additional set of 234 patients from the same institution. The performance of the model was good with an AUC of 0.864 (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Calibration of the predictive model in the modeling group.

All patients were grouped into deciles according to their predicted probabilities. The mean predicted probability of each decile was plotted against the actual probability of axillary lymph node (ALN) metastasis. The reference line represents perfect equality of the predicted probability and the actual incidence of ALN metastasis. The coefficient of determination (R2) reflects the calibration of the model. The calibration of the model was considered acceptable with R2 of 0.9375.

Figure 4. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the predictive model for the validation group.

The reference line with a slope of 1 indicates an area under the ROC curve value of 0.5, which means that the probability of axillary lymph node (ALN) metastasis is equal to the toss of a coin. An area under the ROC curve (AUC) value of 1 represents perfect discrimination of a patient with positive ALN from the one with negative ALN. The model showed good performance with AUC of 0.864.

Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy and false-negative rate (FNR) of the model for several predicted probability cut-off values in the validation group are shown in Table 4. The FNRs of the model were 0% and 5.3% for the predicted probability cut-off points of 7.1% and 13.8%, respectively.

Table 4. Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of our model in low-risk predictive patients in validation group.

| Predicted risk | Patient number and percentage (%) | Number of patients with ALN metastasis | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | FNR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <7.1% | 6 (2.6) | 0 | 100 | 6 | 100 | 0 |

| <13.8% | 19 (8.1) | 1 | 99.2 | 17.8 | 94.7 | 5.3 |

| <18.2% | 23 (9.8) | 2 | 98.5 | 20.8 | 91.3 | 8.7 |

| <20% | 29 (23.1) | 5 | 96.2 | 23.8 | 82.8 | 17.2 |

| <30% | 55 (23.5) | 14 | 89.5 | 40.6 | 74.5 | 25.5 |

| <40% | 78 (33.3) | 16 | 88 | 61.4 | 79.5 | 20.5 |

Validation group (n = 234): patients with positive lymph node (n = 133, 56.8%); patients with negative lymph node (n = 101, 43.2%).

ALN: axillary lymph node; FNR: false negative rate.

Discussion

A precise noninvasive evaluation of ALN status preoperatively, although challenging, is very important for optimization of the treatment plan for patients with early breast cancer. Efforts have been made to construct a more precise and reliable tool for assessing the ALN status by using one, (e.g. ultrasound or digital mammography (MMG)), or a combination (e.g. magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound and MMG) of current imaging modalities used in breast cancer patients, but the accuracy kept varying with less satisfactory. The FNRs of axillary ultrasound examination for determining lymph node metastasis were reported as 16.7% and 22.9%15,16. When combined with other modalities, such as MRI, physical examination, MMG, or positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), the FNRs declined slightly, but were still as high as 14–16.9%15,16. Besides, the MRI and PET/CT examinations are too expensive to be routinely implemented in all patients. Diepstraten et al.13 reported that the FNRs of ultrasound-guided ALN biopsy ranged from 15% to 40%, with a pooled estimate of 25%, which was much higher than the overall FNR of SLNB reported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)17. Moreover, the ultrasound-guided lymph node biopsy is an invasive procedure, which may increase risks like blood vessel damage. Development of a noninvasive, more practical, reliable and accurate clinical decision-making tool for predicting the probability of ALN metastasis is of great importance in clinical practice.

In the present study, we developed a predictive model to estimate the probability of ALN metastasis in early breast cancer patients with positive axillary ultrasound findings. The model was well calibrated in the modeling group and showed good performance for evaluation of nodal metastasis in the validation group with an AUC of 0.864. Some clinicopathological variables showed statistically significant differences between the modeling group and the validation group, which might be due to the relatively small sample size. Despite significant difference existed, the absolute median number of transverse diameter and cortical thickness between two groups matched closely. That explains why the model still performed well in the validation group, although transverse diameter and cortical thickness served as independent risk factors for node metastasis. Our result emphasizes the stability of the model when applied to a different set of patients. Since stability serves as one of the most important quality parameters for a well-developed model, the stability of our model showcased in this study provides us confidence that the model is generally applicable to other Asian patient populations, although further validation in independent patient cohorts is desirable.

According to NSABP B-3218, micrometastastic disease was an independent prognostic factor for patients with initially negative SLN. Therefore, in our study, IHC staining was routinely performed to detect micrometastasis when no tumour cells were identified on H&E staining. In a multivariate analysis, six variables emerged as independent predictors for ALN metastasis and were included in the final model. They were clinical tumour size, histological grade, ER, transverse diameter, cortical thickness and absence of hilum of the lymph node as detected by ultrasound. Tumour size and histological grade have been reported to be risk factors for ALN metastasis in many other studies19,20,21,22,23,24, as could be confirmed by our results. The predictive value of ER and PR status in previous studies was uncertain, with some studies showing no predictive value for ER and PR status19,21,22,24, and others reporting that lower risk of ALN metastasis was found in tumours with negative expression of either ER25 or PR23,26. In this study, we found that ER overexpression was associated with higher probability of ALN metastasis. This finding may seem counterintuitive, but is similar to the findings from Bevilacqua et al.20. Although we do not know the actual reason of this phenomenon, we hypothesize that ER negative tumours may prefer hematogenous metastasis rather than lymphatic metastasis.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first ALN metastasis predictive model mainly incorporating ultrasound parameters reported in the English literature. Preoperative axillary ultrasound is a simple test that is routinely used for assessing the clinical ALN status in breast cancer patients. According to previous reports, thickening of cortex and disappearance of hilum were associated with lymph node metastasis14,16. The result of our study is in line with those findings. In our final nomogram, transverse diameter, cortical thickness and hilum status were included as independent predictors of ALN metastasis. For an expert radiologist, axillary ultrasound can almost always identify lymph nodes and access the node morphology27,28,29. In that case, the three ultrasound parameters incorporated in our model could be easily obtained in almost all breast cancer patients, which will ensure the application of the model. Around 15–40% of patients with positive axillary ultrasound may have tumour-negative nodes on pathological evaluation14,30,31,32. Obviously, it is of great value to identify those patients preoperatively, for whom SLNB or even omitting surgical intervention may be a suitable option. We created the predictive model based on data from patients with positive axillary ultrasound findings in order to select those patients with a low risk of node metastasis.

In our study, patients with a predictive probability of less than 7.1% presented with no apparent lymph node metastasis. When the predicted probability cut-off point was set at 13.8%, the FNR of the model was only 5.3%, much lower than the FNR of SLNB reported by ASCO (overall 8.4%, range 0–29%)17. In that condition, omission of SLNB appears to be acceptable after thorough discussion with patients, especially in elderly patients with comorbid conditions. The pathological ALN status is not the only determinant to decide whether a patient should receive systemic adjuvant therapy or not. Histological grade, molecular subtype, tumour type, tumour size, and age of the patient should also be taken into consideration. In our study, only two patients, with an estimated predictive value of less than 13.8%, did not receive systemic therapy according to local guidelines. That is to say, patients would not be undertreated in terms of systemic therapy although they did not receive axillary surgery. Our model could provide doctors with a tool to estimate the probability of ALN metastasis and help them weigh the risks and benefits of SLNB more appropriately. Ultimately, this may prevent selected patients from undergoing unnecessary axillary surgery and associated comorbidity.

To our knowledge, several models have been developed to predict the probability of ALN metastasis, with reported AUC ranging from 0.702 to 0.7920,21,33,34. Among these models, the model developed by Bevilacqua et al. from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in 2007 is the most widely used. The MSKCC model produced an AUC of 0.754 when validated in another patient cohort from the same center20. Subsequently, the model was validated in a German breast cancer patient cohort24 and two Chinese breast cancer patient cohorts25,33, with an AUC of 0.78, 0.71 and 0.73, respectively, all showing a reasonable ability in distinguishing patients with positive lymph nodes from those with negative nodes. The MSKCC model incorporates nine parameters (tumour type, pathological tumour size, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), tumour location, age, multifocality, nuclear grade, ER and PR), some of which are available only post-operatively, such as pathological tumour size, LVI, and multifocality. This may limit the clinical implication of the model, and thus a second surgical procedure might be needed. Two more predictive models reported by Takada et al.34 and Chen et al.33 also require parameters that are not available preoperatively. We believe that, when compared with those models, our model shows some advantages. First, our model contains only six variables that are all routinely available prior to surgery, e.g. histological grade and hormone receptor status can be obtained after core needle biopsy of the primary tumour. This is expected to facilitate the clinical utility of the model in different settings, irrespective of infrastructure. Second, our model showed an excellent discrimination, yielding an AUC of 0.864. By calculating the individual probability of ALN metastasis using our user-friendly web-based calculator, doctors could inform their patients regarding their chances of having a positive ALN preoperatively. This knowledge will allow patients to better participate in discussing the treatment strategy on axillary nodes and make an informed decision.

Although our model provides a promising predictive value in early breast cancer patients, it still has some limitations. First, the model was only validated in one small internal validation cohort (n = 234). It needs to be further validated in external validation groups to evaluate its predictive ability and generalizability. Second, risk factors like clinical tumour size, cortical thickness and transverse diameter of lymph node may differ when measured by different doctors due to inter-observer variability. Taking the above-mentioned into account, our model cannot be considered an alternative to SLNB, even in patients with a low predicted probability of ALN metastasis. Validation studies using independent datasets to judge our model on its merits are encouraged. After further validation in clinical practice, this model may support increasingly limited surgical approaches to the axilla in breast cancer.

Methods

Study design and patients population

This study enrolled a consecutive series of 322 patients with primary invasive early breast carcinoma treated at the Breast Center, Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College from November 2009 to April 2014 for developing the predictive model. An additional set of 234 consecutive patients treated at the same institution between May 2014 and November 2015 were enrolled as the validation group.

The inclusion criteria were female patients with early invasive breast cancer (clinical TNM stage according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual35: T1-3 and N0-1), having positive axillary ultrasound findings (defined as at least one lymph node visible by ultrasound36), and receiving a successful SLNB or ALND. Patients with local advanced disease (TNM stage according to the 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual35: T4 or N2-3), neo-adjuvant treatment, or bilateral breast cancer were excluded.

All patients underwent a preoperative axillary ultrasound assessment using the IU22 (PHILIPS, The Netherlands) and ACUSON S2000 (SIEMENS, Germany) with a high-frequency transducer (12 to 15 MHz). Characteristics of lymph nodes including number of nodes, transverse diameter, longitudinal diameter, longitudinal-to-transverse axis ratio, cortical thickness, absence of medulla and absence of hilum were recorded. The ultrasound findings were reviewed and re-assessed by an experienced radiologist (C.C.) with more than 10 years of experience in breast ultrasound imaging. Surgical treatment for the primary disease included breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy with or without breast reconstruction. Systemic and radiation therapy were performed according to the local clinical practice guideline.

We utilized each of the following variables: age at diagnosis, menopausal status, clinical tumour size, tumour location, histological type, histological grade, ER, PR, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her-2), Ki-67, P53, vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C), as well as molecular subtype, and all above-mentioned variables of lymph node on ultrasonography. If more than one lymph node was detected, the variables were assessed on the lymph node most suspicious for metastasis.

Tumour tissues were obtained from paraffin embedded specimens for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) staining. The technique of histopathological analysis has been described previously37. Grading of invasive tumour was scored according to the Nottingham (Elston-Ellis) modification of the Scarf-Bloom-Richardson grading system. All nodes were examined postoperatively with serial section H&E staining. IHC staining was performed to determine whether micrometastasis (0.2–2 mm cancer foci) existed or not when no cancer cells were identified on H&E staining. ER37, PR37, P5337, and VEGF-C38 were considered positive if immunostaining was positive in more than 10% of tumour cells. Her-2 positivity was defined as a score of 3+ on IHC37 or amplification on FISH39. Ki-67 was considered positive if nuclear staining of tumour cells was >14% and negative if ≤14%19.

Statistical analysis

Differences of continuous variables between groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The chi-square test was performed to compare the rates between different groups. In the modeling group, a univariate analysis was performed to assess risk factors for ALN metastasis. Variables with a p-value less than 0.05 in the univariate analysis were included in a binary logistic regression analysis using a backward selection procedure in order to discover the independent risk factors of ALN metastasis. Variables with a p-value less than 0.05 in the multivariate analysis, as an independent risk factor, were included in an equation for predicting the probability of ALN metastasis. Coefficients for each variable and the constant in the equation were generated based on multivariate analysis. A nomogram was developed to be a graphic representation of the model. To calibrate the model, the patients in the modeling group were grouped into deciles with respect to their predicted probabilities of lymph node metastasis calculated by the equation. For each decile, the mean predicted metastatic probability was compared with the mean actual metastatic rate. The calibration was assessed graphically and by calculation of the coefficient of determination (R2). The predictive model was then validated with an additional set of 234 Chinese patients in the validation group. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn, and the area under the curve (AUC) was used to assess the predictive accuracy of the model. Fit of the model was evaluated by the Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test. Two tailed p-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed by using the statistical software SPSS (version 19, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and “R” (version 3.1.0).

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 declaration of Helsinki and all subsequent revisions. All persons mentioned in the paper gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Qiu, S.-Q. et al. A nomogram to predict the probability of axillary lymph node metastasis in early breast cancer patients with positive axillary ultrasound. Sci. Rep. 6, 21196; doi: 10.1038/srep21196 (2016).

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the funds from Major State Basic Research Development Program (No. 2011CB707705); Natural Science Foundation Committee (No. 31271068), Major International Collaborative Research Project (81320108015) and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory on Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Research.

Footnotes

Yes, there is potential competing financial interests. Rick G. Pleijhuis is a coowner of the online platform Evidencio that makes clinical decision rules accessible to healthcare providers. Other authors declare that they have no conflict of interests

Author Contributions S.Q.Q. and H.C.Z. collected patients’ clinicopathological records, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. F.Z. analyzed the data. C.C. assessed the ultrasound scanning. W.H.H. and J.D.W. collected patients’ clinicopathological records. R.G.P. developed the web-based calculator. G.M.v.D., R.G.P. and G.J.Z. revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. G.J.Z. conceived of and designed the study. S.Q.Q. and H.C.Z. contributed equally to the work. All authors had final approval of the submitted and published versions and are accountable for the work.

References

- Huang W. H. et al. Analysis of clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of 1425 primary breast cancer patients in eastern Guangdong, China. Curr Signal Transd T. 9, 44–49 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee M., George J., Song E. Y., Roy A. & Hryniuk W. Tree-based model for breast cancer prognostication. J Clin Oncol. 22, 2567–75 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velanovich V. & Szymanski W. Quality of life of breast cancer patients with lymphedema. Am J Surg. 177, 184–88 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunsell E., Brisson J. & Deschenes L. Arm problems and psychological distress after surgery for breast cancer. Can J Surg. 36, 315–20 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashikaga T. et al. Morbidity results from the NSABP B-32 trial comparing sentinel lymph node dissection versus axillary dissection. J Surg Oncol. 102, 111–18 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S. A. et al. Prevalence of lymphedema in women with breast cancer 5 years after sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary dissection: patient perceptions and precautionary behaviors. J Clin Oncol. 26, 5220–26 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Breast Cancer Study Group. et al. Randomized trial comparing axillary clearance versus no axillary clearance in older patients with breast cancer: first results of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 10–93. J Clin Oncol. 24, 337–44 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli G. et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in older patients with T1N0 breast cancer: 15-year results of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 256, 920–24 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donker M. et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981/22023 AMAROS): a randomized, multicentre, open-label, phase 3non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 15, 1303–10 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano A. E. et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 305, 569–75 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti V. et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 14, 297–305 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilini O. & Veronesi U. Abandoning sentinel lymph node biopsy in early breast cancer? A new trial in progress at the European Institute of Oncology of Milan (SOUND: Sentinel node vs Observation after axillary UltraSouND). Breast. 21, 678–81 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diepstraten S. C. et al. Value of preoperative ultrasound-guided axillary lymph node biopsy for preventing completion axillary lymph node dissection in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 21, 51–59 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nori J. et al. Role of axillary ultrasound examination in the selection of breast cancer patients for sentinel node biopsy. Am J Surg. 193, 16–20 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S. O. et al. The comparative study of ultrasonography, contrast-enhanced MRI, and (18)F-FDG PET/CT for detecting axillary lymph node metastasis in T1 breast cancer. J Breast Cancer . 16, 315–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente S. A. et al. Accuracy of predicting axillary lymph node positivity by physical examination, mammography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Surg Oncol. 19, 1825–30 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman G. H. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline recommendations for sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 23, 7703–20 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver D. L. et al. Effect of occult metastases on survival in node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 364, 412–21 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie F. et al. A logistic regression model for predicting axillary lymph node metastases in early breast carcinoma patients. Sensors (Basel). 12, 9936–50 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua J. L. et al. Doctor, what are my chances of having a positive sentinel node? A validated nomogram for risk estimation. J Clin Oncol. 25, 3670–79 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meretoja T. J. et al. A predictive tool to estimate the risk of axillary metastases in breast cancer patients with negative axillary ultrasound. Ann Surg Oncol. 21, 2229–36 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer L. T. et al. A prediction model for the presence of axillary lymph node involvement in women with invasive breast cancer: a focus on older women. Breast J. 20, 147–53 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viale G. et al. Predicting the status of axillary sentinel lymph nodes in 4351 patients with invasive breast carcinoma treated in a single institution. Cancer. 103, 492–500 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar M. et al. Good prediction of the likelihood for sentinel lymph node metastasis by using the MSKCC nomogram in a German breast cancer population. Ann Surg Oncol. 16, 1136–42 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu P. F. et al. Risk factors for sentinel lymph node metastasis and validation study of the MSKCC nomogram in breast cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 42, 1002–07 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M. J., Skinner K. A. & Lomis T. J. Predicting axillary nodal positivity in 2282 patients with breast carcinoma. World J Surg. 25, 767–72 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. T. et al. Ultrasonographic demonstration of normal axillary lymph nodes: a learning curve. J Ultrasound Med. 14, 823–27 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh Y. S., Ellenbogen S. & Banerjee B. Preoperative axillary ultrasound scan: its accuracy in assessing the axillary nodal status in carcinoma breast. Breast. 11, 49–52 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassallo P., Wernecke K., Roos N. & Peters P. E. Differentiation of benign from malignant superficial lymphadenopathy: the role of high-resolution US. Radiology. 183, 215–20 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachs A. et al. Accuracy of axillary ultrasound in preoperative nodal staging of breast cancer - size of metastases as limiting factor. Springerplus. 2, 350 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. C. et al. Consequences of axillary ultrasound in patients with T2 or greater invasive breast cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 18, 72–77 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. H. et al. Impact of preoperative ultrasonography and fine-needle aspiration of axillary lymph nodes on surgical management of primary breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 18, 738–44 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. Y. et al. Predicting sentinel lymph node metastasis in a Chinese breast cancer population: assessment of an existing nomogram and a new predictive nomogram. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 135, 839–48 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada M. et al. Prediction of axillary lymph node metastasis in primary breast cancer patients using a decision tree-based model. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 12, 54 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breast in AJCC cancer staging manual 7th edn (eds Edge S. et al.) 345–347 (Springer, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- Kuenen-Boumeester V. et al. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer patients. A preoperative staging procedure. Eur J Cancer. 39, 170–74 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu S. Q. et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic strategy and the most efficient prognostic factors of breast malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Sci Rep . 3, 2529 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q. W. et al. Expression and clinical significance of extracellular matrix protein 1 and vascular endothelial growth factor-C in lymphatic metastasis of human breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 12, 47 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff A. C. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 25, 118–45 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]