Abstract

Regeneration of the visual pigment by cells of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is fundamental to vision. Here we show that the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor, MITF, which plays a central role in the development and function of RPE cells, regulates the expression of two visual cycle genes, Rlbp1 which encodes retinaldehyde binding protein-1 (RLBP1), and Rdh5, which encodes retinol dehydrogenase-5 (RDH5). First, we found that Rlbp1 and Rdh5 are downregulated in optic cups and presumptive RPEs of Mitf-deficient mouse embryos. Second, experimental manipulation of MITF levels in human RPE cells in culture leads to corresponding modulations of the endogenous levels of RLBP1 and RDH5. Third, the retinal degeneration associated with the disruption of the visual cycle in Mitf-deficient mice can be partially corrected both structurally and functionally by an exogenous supply of 9-cis-retinal. We conclude that the expression of Rlbp1 and Rdh5 critically depends on functional Mitf in the RPE and suggest that MITF has an important role in controlling retinoid processing in the RPE.

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) not only plays critical roles in eye development but also in normal photoreception. It is involved in nutrient and metabolite flow, maintenance of the blood-retinal barrier, ionic homeostasis, regeneration of visual pigment, and phagocytosis of shed photoreceptor outer segments1. Not surprisingly, RPE defects lead to photoreceptor dysfunction, retinal degeneration, loss of visual acuity, and blindness1,2.

Prominent among the many functions of the RPE is its role in the visual cycle, a process responsible for reconstituting 11-cis-retinal from all-trans retinol. After interaction with photons, photoreceptors release all-trans-retinol, which is taken up by RPE cells and converted to an all-trans-retinyl ester by lecithin retinol acyltransferase (LRAT). Subsequently, the isomerase RPE65 converts the all-trans-retinyl ester to 11-cis retinol. 11-cis-retinol is then oxidized to 11-cis-retinal by several 11-cis-retinol dehydrogenases, including RDH5 and RDH11. 11-cis retinal, which, like 11-cis-retinol, binds RLBP1 (also known as CRALBP), is then released from the RPE and taken up by photoreceptors to reconstitute opsin to the light sensitive rhodopsin1.

Mutations in the genes encoding proteins implicated in the visual cycle have recently emerged as the underlying genetic defects responsible for a number of retinal disorders3,4. Among them, mutations in Rlbp1 and Rdh5 are associated with retinal dystrophies and dysfunctions such as retinitis pigmentosa, Newfoundland rod/cone dystrophy, retinitis punctata albescens, and Bothnia dystrophy or fundus albipunctatus4,5,6. To provide a deeper understanding of the role of these two genes, we here focus on the regulation of their expression and identify MITF as one of their major transcriptional regulators.

MITF is a member of the microphthalmia family of transcription factors (MiT). It is expressed at various levels in a variety of cell types, including neural crest-derived melanocytes and RPE cells where it plays prominent roles in development7,8. In mice, for instance, mutant alleles such as microphthalmia-vga9 (Mitf mi−vga9) not only cause loss of pigmentation in the skin, but also microphthalmia and retinal degeneration due to abnormalities in RPE structure and function8,9. Other Mitf mutant alleles, such as microphthalmia-brownish (MitfMi−b) and microphthalmia-vitiligo (Mitfmi−vit), however, do not lead to microphthalmia but to postnatal retinal degeneration10,11. MITF is well known to regulate the expression of tyrosinase and tyrosinase-related protein-1, whose mutations are associated with Oculocutaneous Albinism and Pigmentary Glaucoma12,13, and of BEST1, whose mutations cause Best Macular Dystrophy14. Nevertheless, little is known about MITF’s potential involvement in the regulation of the visual cycle and whether the regulation of visual cycle genes by MITF contributes to retinal degeneration.

Here, we focus on Rlbp1 and Rdh5 and their regulation by MITF based on several observations. First, previous results have shown that in Mitf-vit mutant RPE retinyl ester levels are significantly elevated but that the accumulation of retinyl ester is not due to increased LRAT activity15, suggesting that dysregulation of other genes may be involved. Second, preliminary experiments indicated that visual cycle genes are down-regulated in Mitf-deficient mouse optic cups and are abundantly expressed in MITF-positive, fully differentiated RPE cells.

Our results show that the visual cycle genes Rlbp1 and Rdh5 expression are reduced in the RPE of P11 and optic cups of E12.5 of Mitf mutant mouse embryos, and Rlbp1 and Rdh5-expression is missing in Mitf mutant embryonic RPE cells. In addition, RLBP1 and RDH5 expression directly correlates with experimental manipulation of MITF levels in the human RPE cell line ARPE-19 cells. Finally, addition of exogenous 9-cis-retinal partially rescues retinal degeneration in Mitf-deficient mice, suggesting that Mitf regulation of visual cycle genes can be functionally relevant for the pathogenesis of retinal degeneration.

Results

Impairment of visual cycle gene expression in Mitf-deficient retina

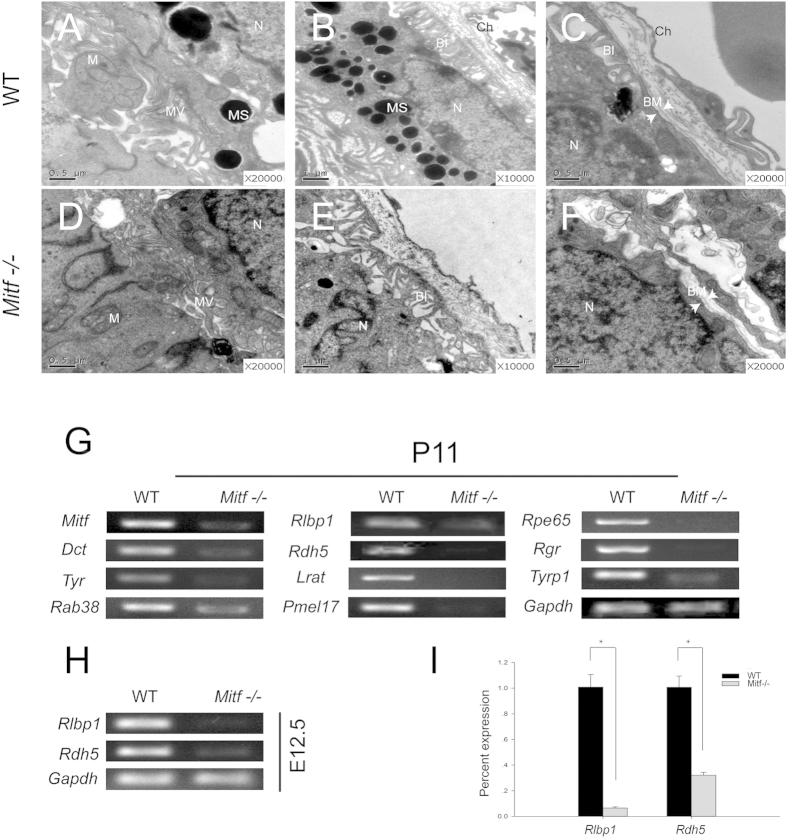

It has been shown previously that RPE development is disrupted in Mitf mi-vga-9 homozygous embryos (hereafter called Mitf−/−)9,16, but the ultrastructure of the mutant RPE has not been examined. Examination by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that the RPE of Mitf−/− P0 and P20 mice displayed apical microvilli and basal infoldings also seen in wild-type RPE but they were sparse and disorganized. In addition, Bruch’s membrane was interrupted and melanosomes and melanin were absent (Fig. 1A–F). These results indicated that although the RPE was retained in Mitf−/− mice, its ultrastructure was abnormal.

Figure 1. Abnormal RPE ultrastructures and decreased expression of visual cycle genes in Mitf−/− mice.

(A–F) P0 (A–E) and P20 (C,F) RPE ultrastructures of WT and Mitf−/− mice revealed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). (A,D) show the interface between RPE and photoreceptor cells in WT and Mitf−/− mice, respectively. The RPE in Mitf−/− displayed thickened and shortened microvilli as compared to WT. The microvilli in the apical surface of the RPE are indicated by MV. B and E show the basal part of the RPE in WT and Mitf−/−, respectively. Bruch membrane was discontinuous and disintegrated in Mitf−/−. (C,F) show the basal infoldings of RPE in WT and Mitf−/− mice, respectively. The basal infoldings of RPE were sparse and disordered in Mitf−/− when compared with that of WT. BI, basal infoldings; BM, Bruch’s membrane; Ch, choroid; M, mitochondria; MS; melanosome; MV, microvilli; N, nucleus. (G) RT-PCR analysis of the expression of visual cycle and pigmentation genes in P11 retinas/RPE of WT and Mitf−/− mice. (H) RT-PCR analysis of the expression of Rlbp1 and Rdh5 in E12.5 optic cups of WT and Mitf−/− mice. (I) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of Rlbp1 and Rdh5 expression in WT and Mitf−/− optic cups at E12.5. RNA levels of Rlbp1 and Rdh5 were normalized to those of Gapdh. The experiments were performed in triplicates and the error bars represent the S.E. *indicates P < 0.05. Gapdh was used as internal control.

It has previously been shown that retinyl ester levels were significantly elevated in Mitf-vit mutant RPE, without, however, showing alterations in LRAT activity15. Hence, we first examined the expression of visual cycle genes in wild type and Mitf−/− retina/RPE preparations in comparison to the expression of pigmentation-related genes, which are known to be regulated by Mitf. At P11, the expression of visual cycle genes Rlbp1 and Rdh5 as well as Lrat, Rpe65, and Rgr were significantly decreased in Mitf−/− retina/RPE, as was Tyr which encodes the rate-limiting enzyme for melanin synthesis (Fig. 1G). Interestingly, further examination revealed that in wild type, though not in mutant, Rlbp1 and Rdh5 were expressed in eye vesicles already at E12.5 when the RPE develops (Fig. 1H,I). In contrast, Lrat, Rpe65, and Rgr were not expressed at these early stages (not shown). These results suggest that Mitf regulates Rlbp1 and Rdh5 gene expression both during development and after birth.

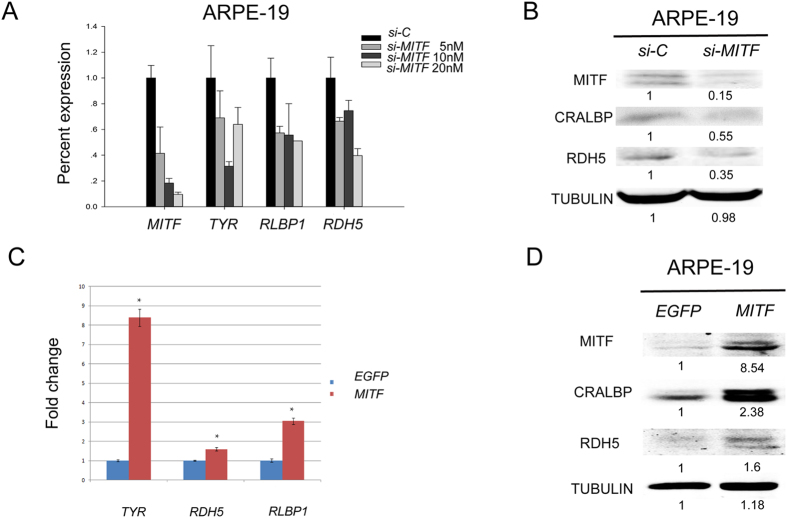

MITF regulates the expression of RLBP1 and RDH5 in RPE cells

To evaluate whether the regulation of Rlbp1 and Rdh5 was indeed controlled by Mitf, we tested whether the inhibition or overexpression of MITF can affect the endogenous expression of RLBP1 and RDH5 in a human RPE cell line. We first transfected cultures of ARPE-19 cells with si-Mitf, a pool of siRNAs directed against MITF or si-NC, a control siRNA. As shown in Fig. 2, knockdown of MITF reduced the expression of RLBP1 and RDH5 RNA and protein (Fig. 2A,B). In contrast, overexpression of MITF using a lentiviral expression system increased the expression of RLBP1 and RDH5 proteins (Fig. 2C,D). These results indicate that MITF regulates the expression of RLBP1 and RDH5 in human RPE cells.

Figure 2. MITF is required and sufficient to induce RLBP1 and RDH5 expression in ARPE-19 cells.

(A) The expression of RLBP1 and RDH5 in ARPE-19 cells transfected with scramble siRNA (si-C) or various concentrations of MITF siRNA (si-MITF). Increased si-MITF concentrations resulted in enhanced MITF knockdown. The expression of the MITF target gene TYR was reduced concomitantly with the reduction of MITF. With the reduction in MITF expression, the expression of RLBP1 and RDH5 was also decreased. (B) Protein expression of RLBP1 and RDH5 was decreased when MITF was knocked-down in ARPE-19 cells. TUBULIN was used as an internal protein loading control. (C) The RNA and protein levels of RLBP1 and RDH5 in EGFP- and MITF-overexpressing ARPE-19. Both RNA and protein expression of RLBP1 and RDH5 were increased when MITF was overexpressed in ARPE19 cells compared to overexpression of EGFP. The experiments were performed in triplicate and the error bars represent the S.E. *indicates P < 0.05.

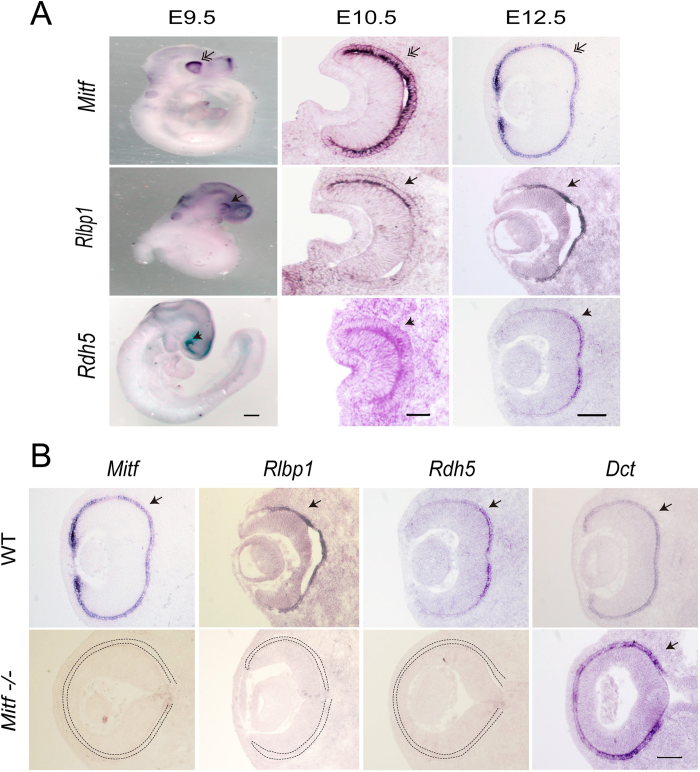

Rlbp1 and Rdh5 expression depends on MITF in vivo

Although Rlbp1 and Rdh5 are expressed in RPE, their spatial and temporal expression patterns during eye development are unclear. By in situ hybridization, the expression of Rlbp1 and Rdh5 was seen already at E9.5 when the optic vesicle is initially formed (Fig. 3A). At this time point, the expression of these two genes was confined to the dorsal part of the optic vesicle where by comparison Mitf expression was highest, but by E12.5 it was extended to the entire presumptive RPE. A comparison between WT and Mitf−/− embryos revealed that the expression of Rlbp1 and Rdh5 depended on intact Mitf while the RPE marker-Dct did not (Fig. 3B), confirming previous studies of Dct expression16. These results suggest that the loss of functional MITF leads to disruption of the expression of visual cycle genes and that Mitf is required for the expression of Rlbp1 and Rdh5 in mouse RPE.

Figure 3. Rlbp1 and Rdh5 expression is dependent on Mitf during mouse eye development.

(A) The spatiotemporal expression patterns of Mitf, Rlbp1 and Rdh5 during mouse eye development by in situ hybridization with an Mitf, Rlbp1, or Rdh5 probe (as indicated on the left-hand side). At E9.5, Mitf was expressed in the whole periphery of optic vesicle, with prominent expression in the dorsal part, while Rlbp1 and Rdh5 expression were observed exclusively in the dorsal part of optic vesicles (double arrows). Rdh5 expanded its expression to the presumptive RPE of the optic cup at E10.5, (arrowheads), while Rlbp1 extended its expression to the presumptive RPE of optic cup at E12.5 (arrows). (B) The expression of Rlbp1 and Rdh5 in WT and Mitf−/− mice embryonic eyes at E12.5 by in situ hybridization with an Mitf, Rlbp1, Rdh5, or Dct probe (as indicated on the top). Note that Rlbp1 and Rdh5 were expressed in RPE of WT mouse embryos, but their expression was absent in Mitf−/−. Dct expression, however, remained intact. Scale bar is 50 μm at E10.5, and 100 μm at E12.5.

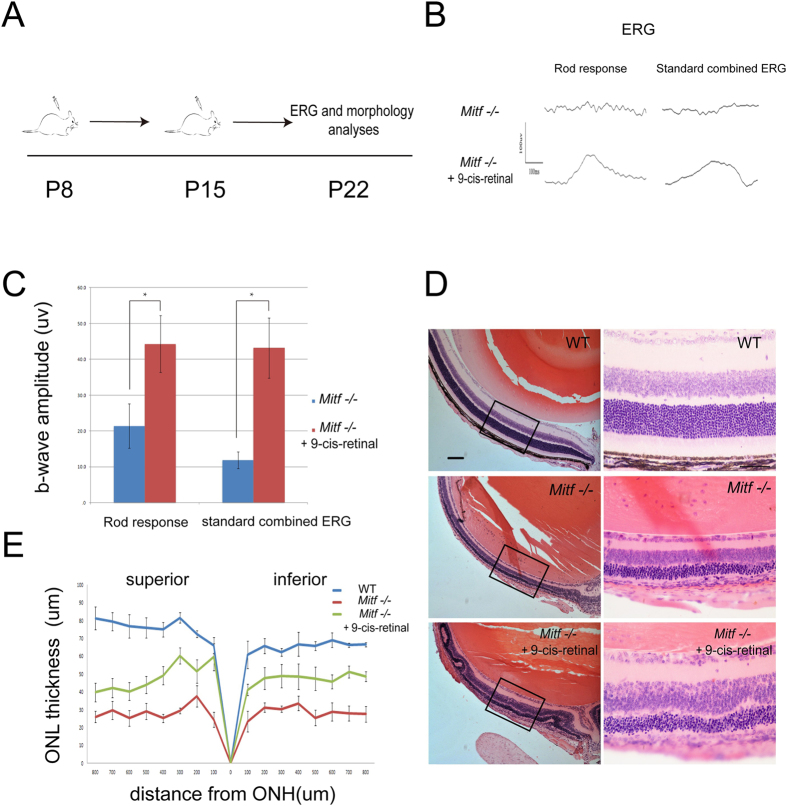

9-cis-retinal treatment partially rescues Mitf −/− retinal morphology and function

In order to address the question of whether the retinal degeneration in postnatal Mitf mutant mice might result in part from impairment of the visual cycle, we made use of the fact that 9-cis-retinal, an analogue of 11-cis-retinal, can rescue retinal degeneration in mice with impaired visual cycle3,17. Hence, we injected 9-cis-retinal into Mitf−/− mice at P8 and P15 and examined their retinal structure and function at P22 (Fig. 4). When injected with solvent alone, the rod response and standard combined electroretinogramm (ERG) was lost in Mitf −/− mice (Fig. 4A,B), and the b wave amplitude of the rod response was 21.4 μv and that of the standard combined ERG 11.9 μV (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, the mice showed severe retinal degeneration, marked by loss of most of the outer segments of photoreceptors and loss of the outer and inner plexiform layers (Fig. 4D) and a general reduction in retinal thickness (Fig. 4E). When 9-cis-retinal was injected, however, Mitf−/− retinas were markedly improved in ERG and structure, and photoreceptor gene expression (Figs 4 and 5). As shown in Fig. 4C, the average b wave amplitude of rod response was increased to 44.3μv and that of the standard combined ERG to 43.2μV. Compared to untreated mutant, the retinal thickness was double, and the ONL, inner plexiform layer, and ganglion cell layer were partially spared from the degeneration seen in the absence of 9-cis-retinal (Fig. 4D,E).

Figure 4. 9-cis-retinal treatment partially recovers visual function and retinal structure in Mitf−/− mice.

(A) Schematic representation of 9-cis-retinal administration in mice for this study. Mice were injected subcutaneously with solvent or 9-cis-retinal in the dorsal torso region at both P8 and P15, and were subjected to ERG examination and morphological analysis at P22. (B) Representative ERG from Mitf−/− mice treated with solvent or 9-cis-retinal at P22. The rod response and standard combined ERG were lost in Mitf−/− mice (n = 12) treated with the solvent only. In contrast, both were partially recovered in Mitf−/− treated with 9-cis-retinal (n = 12). (C) Quantification of b-wave amplitudes from Mitf−/− mice treated with solvent (n = 12) or 9-cis-retinal (n = 12) at P22. Note that Mitf−/− mice treated with 9-cis retinal showed increased b-wave amplitude in rod responses at −25 dB flash intensity and in standard combined ERG at 0 dB flash intensity. The values are represented by mean and SD and were statistically analyzed by unpaired Student’s t-test. *indicates P < 0.05. (D) Histological analysis of WT or Mitf−/− eyes after treatment with either solvent or 9-cis-retinal at P22. Compared with WT mice, Mitf−/− mice treated with solvent suffered from severe retinal degeneration. The thickness of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) in Mitf−/− mice retina was approximately one-fourth of that of wild type, and numbers of nuclei were remarkably reduced. When Mitf−/− mice were treated with 9-cis-retinal, however, the retinal thickness was approximately twice that of Mitf−/− mice treated with solvent, and the numbers of nuclei were significantly increased compared to those of solvent treated mice. The ONL, inner plexiform layer and ganglion cell layer were partially protected. (E) Quantification of the ONL thickness from the optic nerve head (ONH) to the ciliary margin for WT (n = 4) or Mitf−/− mice treated with solvent (n = 5) or 9-cis-retinal (n = 7) at P22. Note that the ONL thickness was significantly increased in Mitf−/− mice treated with 9-cis-retinal compared with Mitf−/− mice treated with solvent.

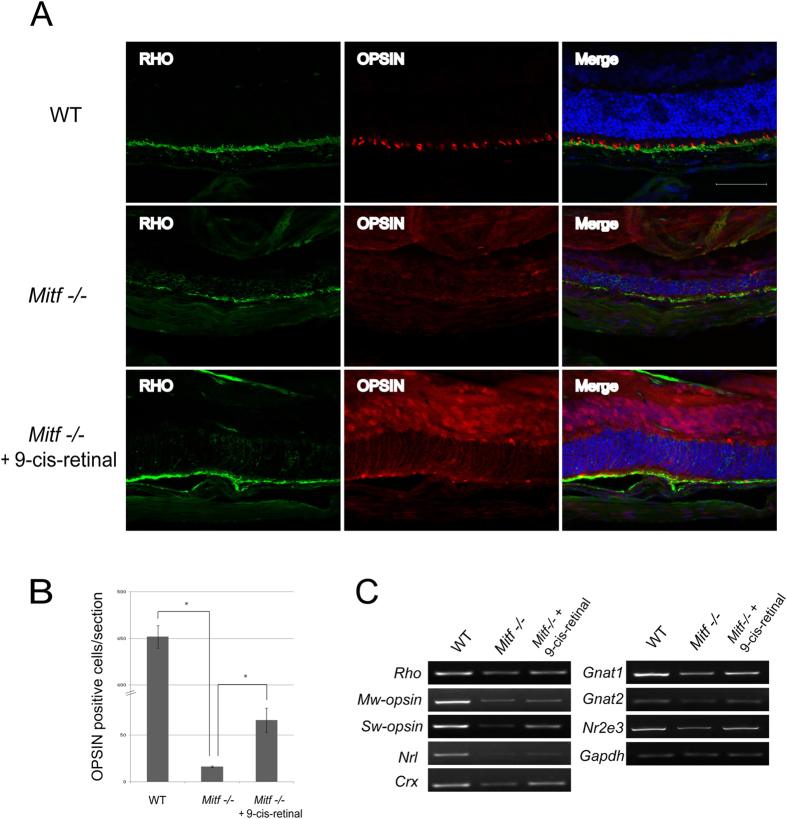

Figure 5. Photoreceptor cells and their related gene expression were maintained in Mitf−/− mice treated with 9-cis-retinal.

(A) RHODOPSIN and OPSIN expression in superior retina of WT and Mitf−/− treated with solvent or 9-cis-retinal. Rod RHODOPSIN was localized to the rod outer segment (ROS), and cone OPSIN was localized to the ONL and the rod outer segment in WT neural retina. In Mitf−/− mice treated with solvent, the RHODOPSIN and OPSIN localization in ROS were decreased and strikingly mislocalized to the cone cell bodies in the ONL. By contrast, RHODOPSIN and OPSIN localization in ROS, especially Rhodopsin, were maintained in Mitf−/− mice treated with 9-cis-retinal. (B) Quantification of OPSIN-labeled cells in retinal ROS of WT, Mitf−/− treated with solvent or treated with 9-cis-retinal. In contrast to WT, the OPSIN-labeled cells in retinal ROS were almost completely lost in Mitf−/− mice treated with solvent, whereas OPSIN-positive cells were partially preserved in Mitf−/− mice treated with 9-cis-retinal. (C) The expression of photoreceptor marker genes in WT, Mitf−/− treated with solvent, and Mitf−/− mice treated with 9-cis-retinal at P22 by RT-PCR. For photoreceptor marker genes, 9-cis retinal administration partially restored S-opsin, M-opsin and Gnat2 expression. Moreover, 9-cis retinal administration also restored expression of the rod-specific genes Rho and Gnat1, as well as genes expressed by both rod and cone cells, including Crx, Nrl, and Nr2e3 expression. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Previous studies had shown that cone M/L-OPSIN expression was lost in visual cycle gene mutant mice, and that administration of 9-cis-retinal prevented this loss18 Therefore, we also examined Opsin and Rhodopsin expression in WT, control Mitf−/− and 9-cis-retinal-injected Mitf−/− mice. As shown in the corresponding panels in Fig 5A, M/L-OPSIN was normally distributed within the cone outer segments in WT but lost in untreated Mitf−/− mice, suggesting cone outer segment degeneration. Administration of 9-cis retinal, however, partially restored M/L-OPSIN expression in the outer segments. As shown in Fig. 5B, the average number of OPSIN positive cells per section was 451 in WT, 16 in untreated Mitf−/−, and 66 in treated Mitf−/− mice. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 5C, RT-PCR results indicated that 9-cis retinal administration partially restored the expression of rod genes (S-opsin, M-opsin, Rho and Gnat1/2) as well as genes expressed by both rods and cones, (Crx, Nrl, and Nr2e). Hence, we conclude that 9-cis-retinal can partially bypass the loss of visual cycle gene expression and prevent retinal degeneration in Mitf mutant mice.

Discussion

Here we provide experimental evidence that the expression of two visual cycle genes, Rlbp1 and Rdh5, depends on functional MITF both in vitro in a human RPE cell line and in vivo in Mitf mutant mice. The finding helps explain the previous observation that retinyl ester levels were elevated significantly in the RPE of Mitf-vit mutant15. In these mutants, the activity of LRAT was not changed so that the increase in retinyl ester was unlikely due to increased production. Rather, it might be due to reduced levels of Rlbp1 and Rdh5 as the products of these two genes are involved in processes of the visual cycle downstream of retinyl ester: RLBP1 binds 11-cis-retinol and RDH5 catalyzes the reaction to 11-cis retinal. In Mitf−/− embryos, however, Lrat expression was reduced, suggesting that retinyl ester levels might not be increased, and hence that the visual cycle was disrupted at even more levels than in Mitf-vit mutants.

Our findings clearly show that by regulating visual cycle genes, Mitf controls the visual cycle and consequently the reconstitution of functional rhodopsin. They do not, however, answer the question of whether it is the mere interruption of the visual cycle, or a more general damage to the RPE, that leads to the associated retinal degeneration. The RPE, after all, has multiple functions in photoreceptor and retinal physiology through its supply of neurotrophic factors, phagocytosis of photoreceptor outer segments, blood retinal barrier maintenance, etc, and its damage may well interfere with any of these functions.

An experimental approach to distinguish between the role of visual cycle interruption and general RPE damage in the cause of retinal pathophysiology was partially provided by the application of 9-cis-retinal, which previously had been shown to substitute for 11-cis-retinal as the final product of the visual cycle and to rescue retinal degeneration in models of isolated visual cycle interruptions. We found, indeed, that postnatal injection of 9-cis-retinal can partially rescue Mitf−/− retinae because gene expression, structure and function were all improved. This was in a way surprising as one might expect that the lack of Mitf in the RPE may have so profound developmental effects that the adjacent retina might be permanently damaged. Nevertheless, it is clear that the rescue was only partial. Several explanations may be offered for this observation. First, the supply of 9-cis-retinal may not have reached high enough levels, or may have occurred too late, to fully rescue photoreceptors and retina. Second, as Mitf is not only expressed in the future RPE but also in the future retina, albeit at low levels, it was conceivable that the retina might be developmentally impaired even if RPE and the visual cycle were normal. Third, as mentioned above, the restoration of only one function, the visual cycle, might just not be enough to fully normalize the structure and function of a retina that is likely severely damaged at multiple levels by the absence of a normal RPE. Following this latter thought, we would predict that the retinal phenotype associated with certain milder Mitf mutations, which might damage the visual cycle but leave other RPE functions largely intact, might more readily be corrected with 9-cis-retinal alone.

In sum, then, our work provides evidence that MITF affects the visual cycle at least through the regulation of RLBP1 and RDH5. Recently, it has also been shown that two other transcription factors present in RPE, SOX9 and OTX2, act synergistically to activate the RLBP1 and RPE65 promoters19. Future work will delineate whether this regulation is direct, operating through enhancers and promoters of the respective genes, or indirect through interspersed factors, what co-operating factors might be involved, and whether the whole set of visual cycle genes is regulated concordantly by MITF alone or in conjunction with SOX9 and OTX2.

Materials and Methods

Animal

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines of the Wenzhou Medical University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. C57BL/6J, FVB, and Mitf mi-vga-9 mutant mice were used for this study. To collect mouse embryos at the indicated time points, the noon of the day a vaginal plug was found was defined as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5).

Conventional PCR and quantitative real-time PCR

For PCR analysis, mouse retinas were collected at postnatal day 11, and optic cups from mouse embryos were isolated at E12.5. The respective tissues were immediately homogenized in Trizol for RNA extraction. Conventional PCR was first conducted to analyze a set of pigmentation-related genes and visual cycle genes in P11 retina and E12.5 optic cups of wild-type and Mitf mi-vga-9 homozygous mice, and quantitative real-time PCR was performed to confirm expression level alterations of the selected genes. Total RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed into cDNA from mouse retinas, optic cups, or cultured cells as previously described20.

Cell culture, lentivirus preparation and infection

The human retinal pigment epithelial cell line (ARPE-19 cell) was obtained from American Type Cell Culture (ATCC) and maintained in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco-BRL, Invitrogen). D407 and 293T cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. For lentivirus preparation, 7.5 μg FUW-Mitf, 5.625 μg Pax2 and 1.875 μg PMD plasmids were cotransfected into 293T cells by polyjet transfection reagent according to the instructions of manufacturer (Signagen). After 48h, the supernatant were concentrated by Lenti-X Concentrator (Clontech). Briefly, lentivirus-containing supernatants were mixed with Lenti-X Concentrator at 3:1 ratio, then the mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 30 minutes to overnight. Samples were centrifuged at 1,500 X g for 45 minutes at 4 °C, then off-white pellets were resuspended in DMEM. For lentivirus infection, ARPE19 or D407 cells were seeded in 6-well plate at 1 × 105 cells per well. After 24 hrs, lentivirus with 8 μg/ml polybrene was added to the culture medium. Six hours after infection, fresh medium was added for 1 hour, and a second round of infection was conducted.

siRNA transfection

ARPE19 cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 4 × 104 cells/well before transfection. When the cell density reached 30% confluence, cells were transfected with appropriate dilutions of 20 μM siMitf pool (Thermo scientific) containing 4 siRNAs targeting different regions of MITF RNA, each at 5μM, using lipojet reagent (Signagen) at the indicated concentrations following the company’s instructions. Briefly, for transfection at a final concentration of 20 nM, 20 pmoles siRNA were diluted into 100 μl working solution of LipoJet™ Transfection Buffer, and 1.5 μl LipoJet™ reagent was added and mixed by pipetting up and down. The transfection complex was incubated for 15 min at RT and added to 1 ml medium in each well. Seventy-two hours post-transfection, cells were collected in Trizol or protein lysis buffer. In all experiments, control siRNA (CONTROL Non-Targeting siRNA; Thermo scientific) was included.

Western blotting

Total protein from Mitf or Control siRNA-treated ARPE19 cells, and EGFP or Mitf-lentivirus-infected ARPE19 cells were subjected to Western blotting with anti-MITF (Abcam, 12039), anti-CRALBP (Thermo scientific, MA1-813), anti-RDH5 (Santa Cruz, sc-98348), anti-TUBULIN (Santa Cruz, sc-5286) antibodies. Western blots were prepared and performed according to a published procedure20.

In Situ hybridization

Embryos at various embryonic days as indicated in the results were collected in PBS and fixed overnight at 4 °C using 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Sectioning and whole mount in situ hybridization were performed according to a published procedure21. The Mitf and Dct riboprobes were described previously22,23. The Rlbp1 riboprobe was kindly provided by Dr Connie Cepko (Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). The Rdh5 riboprobe was obtained by amplifying the 864 bp fragment of the murine Rdh5 coding region from E12.5 C57BL/6J mouse optic cup cDNA using the sense primers 5- GCC GGC CAG TGA TGC TTT C and the antisense primer 5- CGG GGA AGG ATC CAG GTG AG. The PCR product was cloned into TOPO-TA vector (Invitrogen), and verified by sequencing.

9-cis-retinal experiment

For 9-cis-retinal treated experiments, 9-cis-retinal (Sigma) was dissolved in 100% ethanol to generate a 125 mg/ml stock solution. For each experiment, 2 μl of 9-cis-retinal stock was combined with 18 μl ethanol and 180 μl matrigel at 4 °C for a final volume of 200 μl. The mixture was injected subcutaneously into the dorsal torso region as previously described18. 9-cis retinal was omitted from the mixture for all control groups. Mitf mi-vga-9 homozygous and heterozygous littermates were injected subcutaneously at P8 and P15, and reared in darkness. Eye balls were collected at P22 for further examinations as described in the results.

Electroretinography (ERG)

At P22 following solvent or 9-cis-retinal administration, a RETIport system with a custom-built Ganzfeld dome (Roland Consult, Wiesbaden, Germany) was utilized for ERG recording. Overnight dark-adapted mice were anesthetized under dim red light by intraperitoneal injection of 7 μL/g body weight of 6 mg/mL ketamine and 0.9 mg/mL xylazine diluted with 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, containing 100 mM NaCl. Pupils were dilated with 1% tropicamide, and a heating pad was used to keep the body temperature at 38 °C. The corneal electrode was a gold wire loop; a reference electrode was placed on the forehead and a ground electrode was applied subcutaneously near the tail. For dark-adapted ERGs, the intensities of flashes were −5.0, −15, −25,and −35 log scotopic candela sec/m2 (cd. s/m2). Twelve ERG scans were averaged for dark-adapted ERGs. Ganzfeld illumination with white light stimulus was applied for a duration of 2 milliseconds. B-wave amplitudes were defined as the difference between the trough and peak of each waveform.

Immunostaining

For immunostaining, eyes were fixed in 4% PFA at 4 °C for overnight, cryopreserved in 30% sucrose, and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound. Sections (14 μm) were collected on a cryostat, dried at RT for 30 min, and fixed in 2% PFA for 10 min. After rinsing, the sections were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X-100 for 10 minutes and blocked with 10% goat serum for 1 hour at RT. Anti-Rhodopsin (milipore MAB5316) and anti-Opsin (milipore AB5405) were used as primary antibodies, and goat anti-mouse IgG alexa Fluor® 488 (life technologies, A11029) and goat anti-rabbit IgG alexa Fluor® 594 (life technologies, A11037) were used as secondary antibodies. Each staining was performed on slides from at least three animals per condition. Immunostaining results were observed and photographed using a Zeiss confocal microscope.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons between two groups were performed by an unpaired Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Significant differences between groups are noted by *or **.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wen, B. et al. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor regulates the visual cycle genes Rlbp1 and Rdh5 in the retinal pigment epithelium. Sci. Rep. 6, 21208; doi: 10.1038/srep21208 (2016).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Constance L. Cepko for reagents, Yibo Zheng for technical assistant, and Dr. Heinz Arnheiter for reagents and thoughtful comments on the manuscript. This work is supported by the Zhejiang Provincial NSF (Y2101213, LZ12C12001, LY13C090004, LQ13H120004), the National Basic Research Program (973 Program, 2009CB526502), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30971467, 31171408, 81570892), and the Research Grant of Wenzhou Medical University.

Footnotes

Author Contributions B.W. and S.L. designed, performed experiments, analyzed data, and B.W. wrote the draft; H. L., Y. C., X. M. and J. W. performed experiments and collected data of experiments; F. L. and J. Q. contributed reagents; L. H. designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper.

References

- Strauss O. The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol Rev. 85, 845–881 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond S. M. & Jackson I. J. The retinal pigmented epithelium is required for development and maintenance of the mouse neural retina, Curr Biol. 5, 1286–1295 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D. A. et al. Mutations in the gene encoding lecithin retinol acyltransferase are associated with early-onset severe retinal dystrophy. Nat Genet. 28, 123–124 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D. A. & Gal A. Vitamin A metabolism in the retinal pigment epithelium: genes, mutations, and diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 22, 683–703 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maw M. A. et al. Mutation of the gene encoding cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 17, 198–200 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang P. H.,Kono M., Koutalos Y., Ablonczy Z. & Crouch R. K. New insights into retinoid metabolism and cycling within the retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 32, 48–63 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L. & Pavan W. J. Transcriptional and signaling regulation in neural crest stem cell-derived melanocyte development: do all roads lead to Mitf? Cell Res. 18, 1163–1176 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnheiter H. The discovery of the microphthalmia locus and its gene, Mitf. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 23, 729–735 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson C. A. et al. Mutations at the mouse microphthalmia locus are associated with defects in a gene encoding a novel basic-helix-loop-helix-zipper protein. Cell . 74, 395–404 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. B. C57BL/6J-vit/vit mouse model of retinal degeneration: light microscopic analysis and evaluation of rhodopsin levels. Exp Eye Res. 55, 903–910 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steingrimsson E. et al.The semidominant Mi(b) mutation identifies a role for the HLH domain in DNA binding in addition to its role in protein dimerization. EMBO J. 15, 6280–6289 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spritz R. A. Strunk K. M. Giebel L. B. & King R. A. Detection of mutations in the tyrosinase gene in a patient with type IA oculocutaneous albinism. N Engl J Med. 322, 1724–1728 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. G. et al. Mutations in genes encoding melanosomal proteins cause pigmentary glaucoma in DBA/2J mice. Nat Genet. 30, 81–85 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T. & Esumi N. SOX9, through interaction with microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) and OTX2, regulates BEST1 expression in the retinal pigment epithelium. J Biol Chem. 285, 26933–26944 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans B. L. & Smith S. B. Analysis of esterification of retinoids in the retinal pigmented epithelium of the Mitf-vit (vitiligo) mutant mouse. Mol Vis. 3, 11–18 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama A. et al. Mutations in microphthalmia, the mouse homolog of the human deafness gene MITF, affect neuroepithelial and neural crest-derived melanocytes differently. Mech Dev. 70, 155–166 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, T. et al. QLT091001, a 9-cis-retinal analog, is well-tolerated by retinas of mice with impaired visual cycles. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 54, 455–466 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, P. H. et al. Effective and sustained delivery of hydrophobic retinoids to photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 51, 5958–5964 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, T. et al. Transcription factor SOX9 plays a key role in the regulation of visual cycle gene expression in the retinal pigment epithelium. J Biol Chem. 289, 12908–12921 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X. et al. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor acts through PEDF to regulate RPE cell migration. Exp Cell Res. 318, 251–261 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus S. K. et al. Mutation of melanosome protein RAB38 in chocolate mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 99, 4471–4476 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potterf S. B. et al. Analysis of SOX10 function in neural crest-derived melanocyte development: SOX10-dependent transcriptional control of dopachrome tautomerase. Dev biol. 237, 245–257 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter L. L. & Pavan W. J. Pmel17 expression is Mitf-dependent and reveals cranial melanoblast migration during murine development. Gene Expr Patterns. 3, 703–707 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]