Abstract

The yield potential of rice (Oryza sativa L.) has experienced two significant growth periods that coincide with the introduction of semi-dwarfism and the utilization of heterosis. In present study, we determined the annual increase in the grain yield of rice varieties grown from 1936 to 2005 in Middle Reaches of Yangtze River and examined the contributions of RUE (radiation-use efficiency, the conversion efficiency of pre-anthesis intercepted global radiation to biomass) and NUE (nitrogen-use efficiency, the ratio of grain yield to aboveground N accumulation) to these improvements. An examination of the 70-year period showed that the annual gains of 61.9 and 75.3 kg ha−1 in 2013 and 2014, respectively, corresponded to an annual increase of 1.18 and 1.16% in grain yields, respectively. The improvements in grain yield resulted from increases in the harvest index and biomass, and the sink size (spikelets per panicle) was significantly enlarged because of breeding for larger panicles. Improvements were observed in RUE and NUE through advancements in breeding. Moreover, both RUE and NUE were significantly correlated with the grain yield. Thus, our study suggests that genetic improvements in rice grain yield are associated with increased RUE and NUE.

Because of population growth, dietary shifts and biofuel consumption, the global food demand will double by 2050. The current rate of increased crop production will be insufficient to satisfy predicted demand1,2, and such problems will be further intensified by dwindling arable land area, environmental damage, climate change, and crop yield stagnation2,3,4,5. Therefore, to meet the global food demand, the yield potential of crops must be dramatically improved6.

Rice is the most important staple food crop in Asia and has significantly contributed to global food security in the past, and will continue to feed approximately half of the global population in the future3,7. The yield potential of irrigated rice has experienced two significant growth periods, with the first period driven by the introduction of semi-dwarfism and the second period driven by the utilization of heterosis8,9. Although multidisciplinary attempts have been made to increase the rice yield potential over the last decade, grain yield stagnation has been observed worldwide4,10,11,12,13. Therefore, understanding the physiological mechanisms underlying historical improvements in the rice yield potential would facilitate the identification of critical constraints for further improvements.

Over the last two decades, a number of studies have been performed to determine yield improvements that occurred through the process of breeding for wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)14, maize (Zea mays L.)15, rice (Oryza sativa L.)16, and soybean (Glycine max Merr.)17. In rice, annual grain yield gains of 75 to 81 kg ha−1 have been obtained for irrigated rice at International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) since 1966, gains of 42 kg ha−1 have been obtained for irrigated rice in Texas since 1944, and gains of 15.7 kg ha−1 have been obtained for upland rice in Brazil since 198416,18,19. In China, genetic improvements have accounted for 62–74% of the yield increase in rice since the 1980s, with the remaining contributions induced by nitrogen fertilizer use and increased temperatures20,21. The harvest index and biomass production have played vital roles in the genetic improvement of rice before and after the 1980s, respectively, at IRRI16. In China, biomass production has been the main factor contributing to yield increases for indica hybrid rice since the late 1970s22, and sink size contributed significantly for japonica inbred rice in the northeast23. However, little is known of the physiological mechanisms underlying the genetic improvements in the grain yield of rice.

Radiation-use efficiency (RUE) is defined as the efficiency of using intercepted radiation to produce biomass by crops, and it is regarded as the only remaining major prospect for improving yield potential24. Recently, increasing attempts have been made to improve RUE by increasing the photosynthetic rate6,12,25,26,27. However, the literature on changes in RUE during genetic improvements to crops remains controversial. Early studies did not observe changes in RUE during the breeding process in wheat28,29, whereas more recent studies in wheat and soybean have demonstrated significantly improved of RUE in newer varieties17,30. Studies on the changes in RUE during genetic improvement in rice are still lacking. Nitrogen (N) is an essential element for plant growth and rice yield, which partially occurs through its influences on photosynthesis and RUE31. Genetic improvements in N uptake (NUP) and N use efficiency for grain production (NUEg) have been found in wheat32, maize33, and cotton34. In rice, a recent study found significantly higher NUP and NUEg in super rice compared with older varieties in Jiangsu Province of China35. However, the relationship between NUE and RUE during the genetic improvement of rice grain yield has rarely been examined.

In this study, the grain yield, yield components, plant morphology, radiation interception, RUE, NUP and NUEg were determined in a two-year field experiment using widely disseminated varieties in various decades since the 1930s in China. We determined the genetic improvements in the grain yield for rice varieties grown from 1936 to 2005 in Middle Reaches of Yangtze River, and found that significant increases in RUE and NUE contributed to the increased grain yields in the advance of rice breeding in Middle Reaches of Yangtze River.

Results

Climatic condition

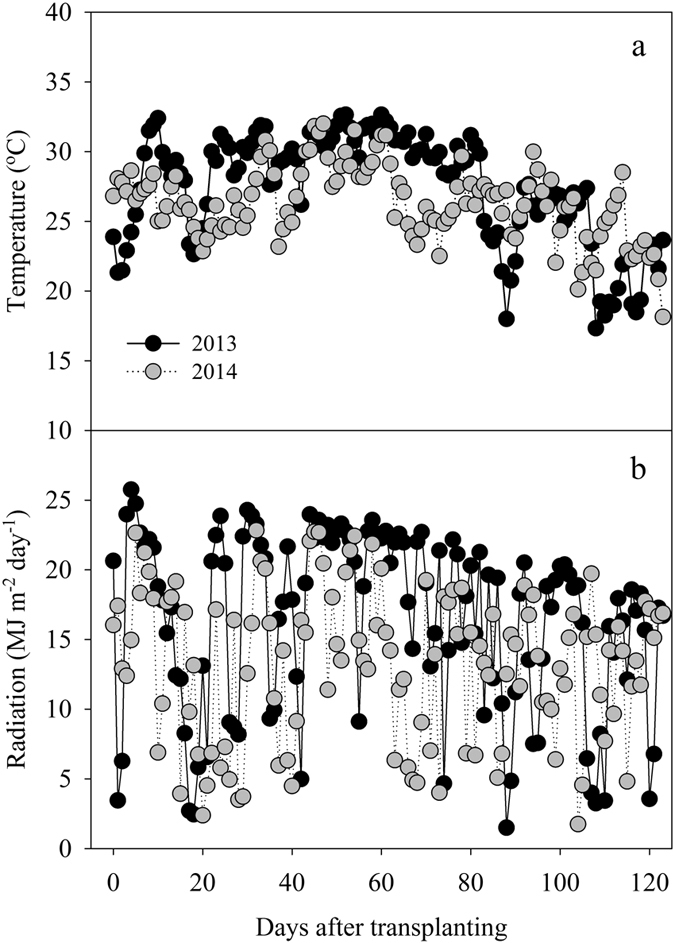

The average daily maximum and minimum temperature during the growing season was 31.5 and 23.2 °C in 2013, respectively, and 30.1 and 22.5 °C in 2014, respectively. The mean daily solar radiation from May to October was 16.4 and 13.3 MJ m−2 day−1 in 2013 and 2014, respectively (Fig. 1). The average daily maximum and minimum temperature during the growing season was 1.4 and 0.7 °C higher in 2013 than in 2014, respectively. The mean daily solar radiation from May to October in 2013 was 23.3% higher than that in 2014 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Daily mean temperature (a) and daily radiation (b) in 2013 and 2014.

Genetic improvements in the grain yield and yield components

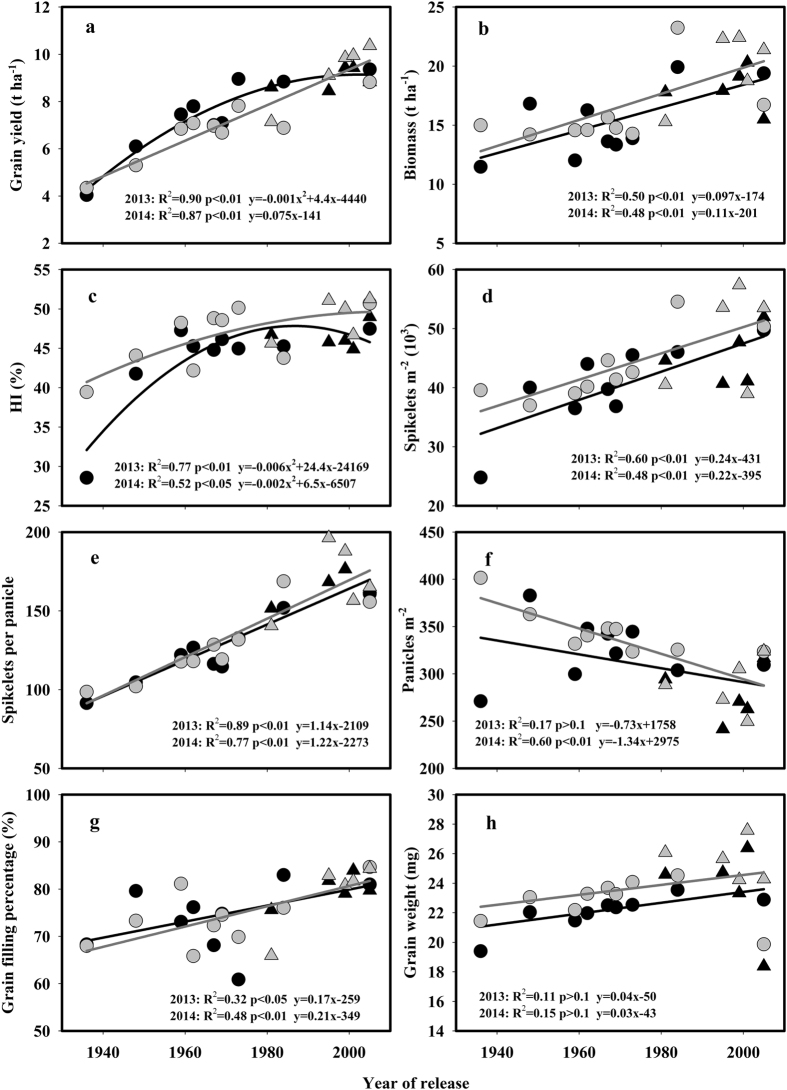

Fourteen varieties that were released and widely cultivated from 1936 to 2005 in Middle Reaches of Yangtze River were assessed in this study (Table 1). The grain yield of newer varieties has been significantly increased compared with that of the older varieties. In 2013 and 2014, the grain yield increased to 61.9 and 75.3 kg ha−1 year−1, respectively, which corresponding to annual increases of 1.18 and 1.16%, respectively. Super-hybrid varieties released after 2000, such as YLY6 and YLY1, achieved grain yields close to 10 t ha−1, whereas the tall variety SLX produced a grain yield of 4.04 t ha−1 in 2013 and 4.33 t ha−1 in 2014 (Table 2). A quadratic relationship between the grain yield and the year of release was observed in 2013, which demonstrated a decreasing trend in the genetic improvements in the grain yield over the last two decades (Table 2; Fig. 2a). In 2014, the grain yield of varieties that had been released before 1990, with the exception of HHZ, the grain yield was higher. This trend resulted in a linear correlation between the grain yield and year of release in 2014 (Table 2; Fig. 2a). The genetic improvements in the grain yield since the 1930s have resulted from both an extended growth season and a higher daily grain yield (Fig. S1).

Table 1. Information of rice varieties grown in different years since 1930s in Middle Reaches of Yangtze River.

| Variety | Abbreviation | Year of release | Type | Province of release |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shenglixian | SLX | 1936 | inbred | Hunan |

| Aizizhan | AZZ | 1948 | inbred | Guangxi |

| Guangchang’ai | GCA | 1959 | inbred | Guangdong |

| Zhenzhu’ai | ZZA | 1962 | inbred | Guangdong |

| Nanjing11 | NJ11 | 1967 | inbred | Jiangsu |

| Ezhong2 | EZ2 | 1969 | inbred | Hubei |

| Guichao2 | GC2 | 1973 | inbred | Guangdong |

| Shanyou63 | SY63 | 1981 | hybrid | Fujian |

| Teqing | TQ | 1984 | inbred | Guangdong |

| IIyou725 | IIY725 | 1995 | superhybrid | Sichuan |

| Liangyoupeijiu | LYPJ | 1999 | superhybrid | Jiangsu |

| Yangliangyou6 | YLY6 | 2001 | superhybrid | Jiangsu |

| Huanghuazhan | HHZ | 2005 | inbred | Guangdong |

| Yliangyou1 | YLY1 | 2005 | superhybrid | Hunan |

The information was from the website of China Rice Data Center (http://www.ricedata.cn/variety/varis/600877.htm).

Table 2. Grain yield and yield components of rice varieties grown in different years since 1930s in Middle Reaches of Yangtze River in 2013 and 2014.

| Variety | Yield (t ha−1) | Panicles m−2 | Spikelets per panicle | Spikelets m−2 (×103) | Grain filling percentage (%) | Grain weight (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | ||||||

| SLX | 4.04 | 271 | 91 | 24.8 | 68.3 | 19.4 |

| AZZ | 6.10 | 383 | 105 | 40.0 | 79.6 | 22.0 |

| GCA | 7.45 | 300 | 122 | 36.5 | 73.1 | 21.5 |

| ZZA | 7.80 | 348 | 127 | 44.0 | 76.2 | 22.0 |

| NJ11 | 7.01 | 342 | 116 | 39.8 | 68.1 | 22.5 |

| EZ2 | 7.09 | 322 | 115 | 36.8 | 74.8 | 22.4 |

| GC2 | 8.95 | 345 | 133 | 45.5 | 60.9 | 22.5 |

| SY63 | 8.61 | 294 | 152 | 44.6 | 75.6 | 24.6 |

| TQ | 8.84 | 304 | 152 | 46.0 | 83.0 | 23.5 |

| IIY725 | 8.45 | 242 | 168 | 40.7 | 81.8 | 24.7 |

| LYPJ | 9.44 | 271 | 177 | 47.7 | 79.1 | 23.3 |

| YLY6 | 9.43 | 263 | 157 | 41.1 | 84.0 | 26.4 |

| HHZ | 8.83 | 317 | 164 | 52.0 | 79.7 | 18.4 |

| YLY1 | 9.36 | 309 | 161 | 49.7 | 81.0 | 22.9 |

| Mean | 7.96 | 308 | 139 | 42.1 | 76.1 | 22.6 |

| LSD (0.05) | 0.67 | 36.7 | 13 | 5.8 | 6.6 | 0.5 |

| 2014 | ||||||

| SLX | 4.33 | 402 | 99 | 39.6 | 68.0 | 21.5 |

| AZZ | 5.30 | 363 | 102 | 37.0 | 73.3 | 23.1 |

| GCA | 6.88 | 332 | 118 | 39.1 | 81.1 | 22.2 |

| ZZA | 7.05 | 341 | 118 | 40.2 | 65.9 | 23.3 |

| NJ11 | 7.00 | 348 | 129 | 44.6 | 72.4 | 23.7 |

| EZ2 | 6.68 | 347 | 119 | 41.4 | 74.6 | 23.3 |

| GC2 | 7.83 | 323 | 132 | 42.6 | 69.9 | 24.1 |

| SY63 | 7.15 | 289 | 141 | 40.5 | 66.0 | 26.1 |

| TQ | 6.90 | 326 | 169 | 54.6 | 76.1 | 24.5 |

| IIY725 | 9.10 | 273 | 196 | 53.6 | 82.9 | 25.7 |

| LYPJ | 9.85 | 305 | 188 | 57.4 | 80.8 | 24.2 |

| YLY6 | 9.95 | 250 | 157 | 39.0 | 81.7 | 27.6 |

| HHZ | 8.85 | 324 | 156 | 50.3 | 84.7 | 19.9 |

| YLY1 | 10.35 | 324 | 165 | 53.5 | 84.4 | 24.3 |

| Mean | 7.66 | 325 | 142 | 45.2 | 75.8 | 23.8 |

| LSD (0.05) | 0.54 | 25 | 10 | 3.7 | 4.4 | 0.36 |

Figure 2. Changes in grain yield and yield components with the year of release of the rice varieties grown in 2013 (black symbols) and 2014 (gray symbols).

Circles and triangles represent data for inbred and hybrid varieties, respectively.

To dissect the causes of these improvements in grain yield, the yield components were measured (Table 2; Fig. 2). Biomass production was significantly increased according to the year of release after the 1980s, and these changes were driven by the utilization of heterosis (Fig. 2). A quadratic relationship between the harvest index and the year of release was observed and had an R2 value of 0.77 in 2013 and 0.52 in 2014. The harvest index of SLX, a tall variety, was 28.6 and 39.4% in 2013 and 2014, respectively, and these values were significantly lower than that of the semi-dwarf varieties (Table 3; Fig. 2c). Among the yield components, a significant increase in spikelets m−2 and grain filling percentage accounted for the genetic improvement in grain yield (Table 2; Fig. 2d,g). Newer varieties tended to present significantly fewer but larger panicles than the older varieties (Table 2 and Fig. 2e,f), and significant changes were not observed in grain weight during the breeding process (Table 2; Fig. 2h).

Table 3. Total incident radiation from transplanting to heading, intercepted radiation from transplanting to heading, radiation interception efficiency from transplanting to heading, biomass, harvest index (HI) and pre-anthesis RUE of rice varieties grown in different years since 1930s in Middle Reaches of Yangtze River in 2013 and 2014.

| Variety | Total incident radiation (MJ) |

Intercepted radiation (MJ) |

Radiation interception efficiency (%) |

Biomass (g m−2) |

HI (%) |

RUE (g MJ−1) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| SLX | 911 | 855 | 708 | 636 | 77.8 | 74.4 | 1147 | 1499 | 28.6 | 39.4 | 1.10 | 1.38 |

| AZZ | 1161 | 869 | 911 | 609 | 78.6 | 70.1 | 1681 | 1421 | 41.8 | 44.1 | 1.05 | 1.38 |

| GCA | 865 | 855 | 598 | 598 | 69.1 | 69.9 | 1201 | 1457 | 47.3 | 48.2 | 1.33 | 1.35 |

| ZZA | 1161 | 869 | 694 | 560 | 59.8 | 64.5 | 1626 | 1458 | 45.3 | 42.2 | 1.55 | 1.83 |

| NJ11 | 963 | 869 | 694 | 595 | 72.1 | 68.5 | 1362 | 1566 | 44.8 | 48.8 | 1.38 | 1.35 |

| EZ2 | 963 | 869 | 690 | 606 | 71.7 | 69.8 | 1334 | 1478 | 46.2 | 48.6 | 1.38 | 1.35 |

| GC2 | 1096 | 1031 | 736 | 559 | 67.2 | 54.2 | 1389 | 1427 | 45.0 | 50.2 | 1.48 | 1.73 |

| SY63 | 1237 | 928 | 996 | 697 | 80.5 | 75.1 | 1779 | 1528 | 46.8 | 45.7 | 1.20 | 1.50 |

| TQ | 1307 | 869 | 1016 | 592 | 77.8 | 68.2 | 1991 | 2324 | 45.3 | 43.8 | 1.30 | 1.68 |

| IIY725 | 1278 | 979 | 1025 | 716 | 80.2 | 73.1 | 1792 | 2232 | 45.8 | 51.1 | 1.20 | 1.58 |

| LYPJ | 1278 | 1033 | 942 | 764 | 73.7 | 74.0 | 1913 | 2242 | 46.0 | 50.1 | 1.38 | 1.53 |

| YLY6 | 1391 | 1033 | 1086 | 771 | 78.1 | 74.7 | 2031 | 1875 | 44.9 | 46.7 | 1.28 | 1.55 |

| HHZ | 1096 | 869 | 759 | 562 | 69.3 | 64.7 | 1550 | 1672 | 49.0 | 50.7 | 1.45 | 1.85 |

| YLY1 | 1237 | 979 | 839 | 683 | 67.9 | 69.8 | 1939 | 2138 | 47.5 | 51.3 | 1.55 | 1.75 |

| LSD (0.05) | – | – | 35 | 22 | 2.82 | 2.33 | 204 | 138 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

The pre-anthesis RUE was calculated as the ratio of aboveground biomass at heading relative to the intercepted global radiation from transplanting to heading.

Genetic improvements in pre-anthesis radiation use efficiency

The total incident radiation from transplanting to heading was increased along with the year of release because of the extended growing season (Fig. S2a). The total incident radiation from transplanting to heading was higher in 2013 than in 2014 because of different weather conditions between the two years (Table 3; Fig. 1). Lodging, which could potentially reduce radiation interception, occurred during grain filling period for some varieties, including SLX, GCA, GC2, SY63, TQ and YLY1 in 2013 and SLX, AZZ, ZZA, SY63, YLY6 and YLY1 in 2014. However, bamboos and ropes were immediately used to help lodging plants stand up so as to minimize the reduction in radiation interception and biomass production. Therefore, light interception was measured from transplanting to heading, and significant changes were not observed in the pre-anthesis radiation interception efficiency, although the leaf area index (LAI) significantly increased along with the advances in breeding (Table 3; Fig. S2b and S3a). Significant correlations (p < 0.1) were observed between the grain yield and intercepted radiation from transplanting to heading in 2013 and 2014 (Fig. S4c).

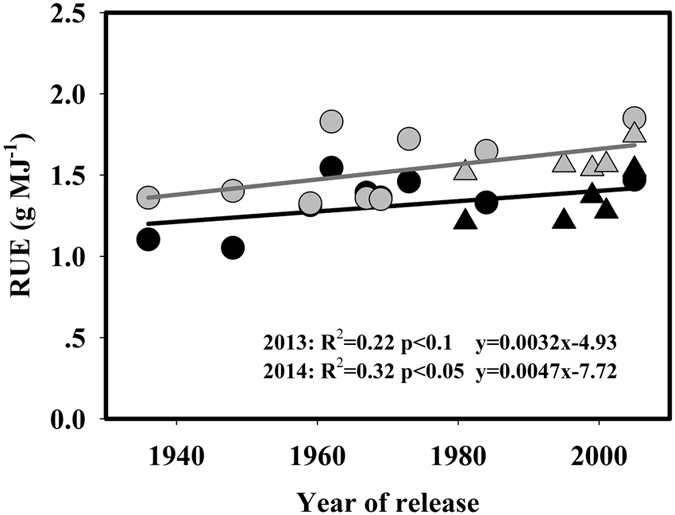

The RUE for pre-anthesis intercepted global radiation (pre-anthesis RUE) was designated as the amount of biomass produced using intercepted global radiation from transplanting to heading, and the values ranged from 1.05 to 1.55 g MJ−1 in 2013 and from 1.35 to 1.85 g MJ−1 in 2014. Significant correlations (p < 0.1) between the pre-anthesis RUE and the year of release were observed in both 2013 (R2 = 0.22) and 2014 (R2 = 0.32). The genetic improvements in the pre-anthesis RUE were 0.0032 and 0.0047 g MJ−1 year−1 on an absolute basis, and 0.45 and 0.40% per year on a relative basis for 2013 and 2014, respectively. The AZZ and SLX varieties released in the 1930s and 1940s had the lowest pre-anthesis RUE, whereas the YLY1 and HHZ varieties released in the 2000s had the highest values (Fig. 3). Significant correlations were observed between the grain yield and pre-anthesis RUE at p < 0.1 in both 2013 and 2014 (Fig. S4d).

Figure 3. Changes in pre-anthesis RUE with the year of release of the rice varieties grown in 2013 (black symbols) and 2014 (gray symbols).

Pre-anthesis RUE was calculated as the ratio of aboveground biomass at heading relative to the intercepted global radiation from transplanting to heading. Circles and triangles represent data for inbred and hybrid varieties, respectively.

Genetic improvement in nitrogen uptake and use efficiency

The total N uptake significantly increased (p < 0.01) along with the year of release, and the values ranged from 138 to 208 kg ha−1 in 2013 and from 150 to 248 kg ha−1 in 2014. In both years, the SLX variety released in the 1930s accumulated the lowest amount of N, whereas the YLY6 and YLY1 varieties, both released in the 2000s, had the highest N uptake (Table 4; Fig. 4a). The N harvest index (NHI) ranged from 33.9 to 62.2% in 2013 and from 48.8 to 65.0% in 2014. In 2013, the correlation between the NHI and the year of release was significant at p < 0.01 (R2 = 0.48), whereas in 2014, the correlation was significant at p < 0.1 (R2 = 0.22) (Fig. 4b).

Table 4. Nitrogen uptake (NUP), nitrogen harvest index (NHI), nitrogen use efficiency for grain production (NUEg) and partial factor productivity of nitrogen fertilizer (PFP) of the varieties grown in different years since 1930s in Middle Reaches of Yangtze River in 2013 and 2014.

| Variety | NUP (kg ha−1) |

NHI (%) |

NUEg (kg kg−1) |

PFP (kg kg−1) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| SLX | 138 | 150 | 33.9 | 53.8 | 29.3 | 28.8 | 26.9 | 28.9 |

| AZZ | 172 | 178 | 57.3 | 52.5 | 36.3 | 29.8 | 40.7 | 35.3 |

| GCA | 157 | 200 | 52.2 | 51.7 | 47.7 | 34.3 | 49.7 | 45.7 |

| ZZA | 179 | 175 | 56.9 | 48.8 | 43.9 | 40.6 | 52.0 | 47.2 |

| NJ11 | 164 | 188 | 55.0 | 60.4 | 43.2 | 37.1 | 46.7 | 46.5 |

| EZ2 | 149 | 189 | 56.4 | 55.6 | 48.7 | 36.1 | 47.3 | 44.6 |

| GC2 | 172 | 168 | 52.0 | 58.9 | 52.3 | 47.0 | 59.7 | 52.1 |

| SY63 | 186 | 178 | 57.1 | 52.7 | 46.4 | 40.3 | 57.4 | 47.6 |

| TQ | 202 | 237 | 57.4 | 57.9 | 44.1 | 29.3 | 58.9 | 45.9 |

| IIY725 | 204 | 229 | 54.0 | 65.0 | 42.3 | 39.8 | 56.3 | 60.7 |

| LYPJ | 189 | 223 | 62.2 | 64.8 | 50.1 | 44.5 | 63.0 | 65.7 |

| YLY6 | 208 | 198 | 59.3 | 57.7 | 46.4 | 50.5 | 62.9 | 66.3 |

| HHZ | 157 | 204 | 59.4 | 54.7 | 58.4 | 43.4 | 58.8 | 58.8 |

| YLY1 | 206 | 248 | 59.1 | 54.4 | 46.1 | 42.0 | 62.4 | 69.1 |

| LSD (0.05) | 32 | 20 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 9.1 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 3.6 |

Figure 4. Changes in the nitrogen uptake, nitrogen harvest index, nitrogen use efficiency for grain production (NUEg), and partial factor productivity of applied nitrogen (PFP) with the year of release of the rice varieties grown in 2013 (black symbols) and 2014 (gray symbols).

Circles and triangles represent data for inbred and hybrid varieties, respectively.

The nitrogen use efficiency for grain production (NUEg) reflects the physiological efficiency of assimilated N for grain yield production, and this value was significantly increased along with the year of release (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4c). Genetic improvements in the NUEg were 0.21 kg kg−1 year−1 (0.84% per year) in 2013 and 0.20 kg kg−1 year−1 (0.57% per year) in 2014. The partial factor productivity of N fertilizer (PFP) reflects the use efficiency of applied N fertilizer in grain yield production, and the value was linearly correlated (p < 0.01) with the year of release with R2 of 0.79 in 2013 and 0.87 in 2014 (Fig. 4d). The PFP ranged from 26.9 kg kg−1 for SLX to 63.0 kg kg−1 for LYPJ in 2013 and from 28.9 kg kg−1 for SLX to 69.1 kg kg−1 for YLY1 in 2014 (Table 4). The genetic improvements in PFP were 0.41 and 0.50 kg kg−1 year−1 on an absolute basis, and 1.18 and 1.16% on a relative basis for 2013 and 2014, respectively. Both the total N uptake and NUEg significantly contributed to the increased grain yield at p < 0.01 in 2013 and 2014 (Fig. S5a,b).

Discussion

Genetic improvements in the grain yield

Taking the whole period of 70 years (from 1936 to 2005), annual gains of 61.9 and 75.3 kg ha−1 in grain yield were observed for rice varieties grown in Middle Reaches of Yangtze River in 2013 and 2014, respectively (Fig. 2a). The rate of genetic improvements in the grain yield showed in present study falls within the range reported by similar studies on rice at IRRI and in Texas16,18. However, the increasing trend was not linear in 2013 (Table 2; Fig. 2a), which is consistent with the recent yield stagnation observed in 79% of rice planting areas in China4. Despite the relatively lower rate of yield increases in the last two decades, breeding efforts have significantly improved the stability of grain yield for varieties since the 1990s. Compared with 2013, grain yield of varieties released prior to 1990s (except for SLX and NJ11) was reduced by 5.8–21.9% in 2014 due to the lower radiation and temperature, whereas grain yield of varieties released after 1990s (except for HHZ) was increased by 4.3–10.6% (Table 2). These results suggest that maintenance breeding has improved the adaptation of newer varieties to the environmental conditions of low radiation and low temperature that have a negative impact on older varieties36.

Grain yield is the product of biomass and harvest index37. Harvest index (HI) was increased significantly when the sd1 gene was utilized in rice breeding in the 1950s38, and this improvement was demonstrated in this study by the significantly lower HI of the tall variety SLX (Table 2; Fig. 2c). Biomass has significantly increased since the end of the 1970s in present study due to the use of heterosis13. On the other hand, the grain yield could be divided into several components, namely spikelet m−2 comprised of panicles m−2 and spikelets panicle−1, grain filling percentage, and grain weight37. Among the yield components, the enlarged sink size caused by the heavier panicles largely accounted for the genetic improvements in grain yield of rice (Table 2; Fig. 2e), and this result was similar to the results found in an analysis of 21 indica hybrid varieties released since 197622 and 12 indica inbred and hybrid varieties released since 1940s35 in China. A moderate number of tillers and large panicles have been the target traits in many rice breeding programs such as the new plant type (NPT) breeding program at IRRI11 and the “super” hybrid rice breeding program in China39. To maintain a high grain filling percentage for the large sink size, other morphological traits must be simultaneously improved to increase biomass production through a combination of the ideotype approach and the utilization of intersubspecific heterosis11. These traits are mostly related to the leaf morphology, such as the leaf length, angle and thickness and LAI of the top three leaves39. Modifications in these plant morphological traits result in the improvements in the light distribution and ventilation within the canopy, which could lead to increases in canopy photosynthesis40,41.

Genetic improvements in RUE

From a physiological perspective, biomass at maturity is the product of total incident radiation during the rice growing period, efficiency with which radiation is intercepted by the crop (radiation interception efficiency), and efficiency with which intercepted radiation converted into biomass42. In the advance of breeding, the total incident radiation during the rice growth period has increased because the growing season has been extended (Fig. S1a and S2a).

RUE is one of the most promising traits for further improvements in the grain yield of rice43, since the efficiency of radiation interception has been significantly improved because plant stature and canopy architecture have been optimized17,24. A question remains as to whether RUE has been increased during the crop breeding process. Many lines of evidence indicate that improvements in RUE have contributed to genetic improvements in the grain yield of many crops, although some has argued that there has been little or no improvement in the conversion efficiency of radiation into biomass6,17,30. In present study, grain yield was significantly correlated with pre-anthesis biomass accumulation and pre-anthesis RUE, but not with post-anthesis biomass accumulation (Fig. S4a,b). RUE was significantly increased along with the year of release of the varieties, and a 27.8% improvement in pre-anthesis RUE was observed over the 70 years covered in present study (approximately 0.43% per year). Similar results have been reported in other crops. In soybean, the efficiency of light conversion to biomass has increased by approximately 36% over 84 years, and together with the improvement in light interception efficiency, these changes are responsible for the observed yield increases in the advance of breeding17. For wheat varieties developed from 1972 to 1995 in the UK, increases in pre-anthesis RUE drove increases in the number of grains and the accumulation of soluble carbohydrates for grain filling, which led to significant improvements in grain yield30. On one hand, the increase in RUE discussed above may have resulted from improvements in the intrinsic photosynthetic rate. In rice, the higher biomass of newer varieties released at IRRI has led to an increased light saturated photosynthetic rate per unit leaf area44. A similar trend has also been found in other studies in rice45,46. On the other hand, the optimization of plant architecture might have decreased the photoinhibition of the top leaves and increased the assimilation rate of lower leaves through an optimized distribution of radiation within the canopy47,48,49. Moreover, higher photosynthetic rates have been observed in rice during the grain filling period in newer varieties 45,46, and such changes could contribute to improvements of RUE during the grain filling period because the photosynthetic rate in the flag leaf after heading was positively correlated with grain yield50.

The pre-anthesis RUE in present study ranged from 1.05 to 1.85 g MJ−1 (Table 3), and these values are similar to that of two super-hybrid, two ordinary hybrid and two inbred rice varieties (1.08–1.66 g MJ−1) grown in Hunan and Guangdong provinces in China51, and to that of seven high-yielding rice varieties (1.29–1.72 g MJ−1) grown in Yunnan province of China and Kyoto of Japan52. Here, a significant difference was observed in pre-anthesis RUE values between 2013 and 2014 (Table 3). Significant variation of the RUE values in two consecutive experimental years was also found in soybean14, and this may have resulted from a significant negative relationship between RUE and intercepted (or incident) radiation42. Recently, a meta-analysis found that RUE was 18% higher in shaded conditions compared with that under full sunlight53.

Genetic improvements in NUE

Several studies demonstrated that breeding for new varieties in rice significantly increased the response of grain yield to N applications18,46, which has led to an overuse of N fertilizers and a reduction in NUE in rice production54. In present study, we demonstrated that N uptake was significantly higher in newer varieties, and NUEg was also significantly increased (Fig. 4). These results are consistent with the results of a recent study in which yield improvements were accompanied by increases in N uptake and NUEg for varieties widely grown in Jiangsu Province over the past 70 years35. Improvements in N uptake and NUEg in the advance of breeding were also found in wheat32, maize33 and cotton55. These results indicate that the empirical viewpoint that newer varieties developed under conditions of ample N application have lower NUE is unauthentic, and show that the lower NUE frequently observed in rice production is mainly caused by inappropriate N management35,54.

In present study, both the increased N uptake and NUEg contributed to the increases in grain yield (Fig. S5a,b), because N significantly affects grain yield through its effect on both the source and sink. Increases in N uptake may have contributed to the improvement in RUE because RUE is dependent on photosynthesis and respiration43, and these metabolic processes are affected by plant N uptake31,56. On the other hand, larger N accumulation in vegetative and early reproductive growth stage is necessary for producing large number of spikelets57, and N top-dressing at the panicle initiation stage was most efficient in increasing spikelet number58. In present study, breeding for high yield is accompanied by a significant increase in the number of spikelets per panicle and N uptake and NUEg. Coincidences of QTLs for yield and its components with genes encoding cytosolic GS and the corresponding enzyme activity were detected in maize59 and rice60. Recently, genetic link between number of spikelets per panicle and nitrogen use efficiency in rice was demonstrated by one gene locus “DEP1”61,62. The gene is first cloned to reduce length of inflorescence internode, and increase number of grains per panicle and grain yield in rice61. Afterwards, a major rice NUE quantitative trait locus (qNGR9) is cloned, and interestingly this gene locus is synonymous with DEP162.

Conclusions

Yield potential has been the main target in rice breeding program under the pressure of increasing population. In this study, the grain yield was significantly increased with the year of release. The genetic improvements in the grain yield partially resulted from the significant increase in RUE. In addition, both nitrogen uptake capacity and nitrogen use efficiency for grain production in newer varieties was improved significantly, which contributed to the increase in grain yield. Currently, the world is facing challenges from environmental pollution, depletion of natural resources, climate change, and growing population, so crop yield potential has to be increased together with resource use efficiency. Compared with the theoretical maxima, there is still room for further improvement in RUE which is an important target in future breeding program. Recent progress in identification of NUE-related genes in rice may facilitate the breeding for high NUE. Overall, RUE and NUE should be concomitantly increased in the future.

Materials and Methods

Experiment design and plant materials

The experiments were conducted in a farmers’ field at Dajin Township (29°51′N, 115°53′E), Wuxue County, Hubei Province, China, during the rice-growing season from May to October in 2013 and 2014. The soil from experiment field had a texture of clay loam with pH 5.47, organic matter 29.10 g kg−1, total N 2.2 g kg−1, available P 12.14 mg kg−1 and available K 92.2 mg kg−1.

Fourteen historical indica mega varieties that were released from 1936 to 2005 were used in this study, and they were all cultivated as middle-season rice in a large-scale area at that time in the Middle Reaches of Yangtze River of China during the last 70 years. Among them, Shenglixian is a tall variety, Aizizhan, Guangchang’ai, Zhenzhu’ai, Nanjing11, Ezhong2, Guichao2, Teqing and Huanghuazhan are inbred rice, Shanyou63 is an ordinary hybrid rice, and IIYou725, Liangyoupeijiu, Yangliangyou6, Yliangyou1 are super high yielding rice varieties that were certified by China’s Ministry of Agriculture (Table 1).

All cultivars were arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications and plot size of 5 × 6 m. Pre-germinated seeds were sown in seedbed. Seedlings (25 d old) were transplanted on 9 June in 2013 and 6 June in 2014. The planting density was 25 hills m−2 at a hill spacing of 30.0 cm × 13.3 cm with three seedlings per hill. Fertilizers included urea for N, single superphosphate for P and potassium chloride for K, and they were applied at the rates of 150 kg N ha−1, 40 kg P ha−1and 100 kg K ha−1. N fertilizer was split-applied at a ratio of 4:2:4 at basal (1 day before transplanting), tillering (7 days after transplanting), and panicle initiation. P and K were all applied at basal. The experimental field was flooded from transplanting until 7 days before maturity. Pests and weeds were intensively controlled using chemicals to avoid yield loss.

Measurements

Plant sampling at heading

Plants from 12 hills in each plot were sampled at heading, and then separated into leaves, stems and panicles. The area of green leaf blades was measured with a Li-Cor area meter (Li-Cor Model 3100, Li-Cor Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA), and expressed as leaf area index (LAI). The dry weights of leaves, stems and panicles were measured after oven-drying at 70 °C to constant weight. The specific leaf weight was calculated as the ratio of leaf weight to leaf area. The aboveground total dry weight was the summation of dry weights in different plant parts.

Yield and yield components

At maturity, plants of 5 m2 in the center of each plot (to avoid border effect) were harvested to determine the grain yield which was adjusted to 14% moisture content. Grain moisture content was measured with a digital moisture tester (DMC-700, Seedburo, Chicago, IL, USA). Grain yield per day was calculated as the ratio of grain yield to total growth duration. Destructive sampling of 12 hills from each plot was conducted to determine the yield components. After the panicle number was counted, the plants were separated into straw and panicles. The straw dry weight was determined after oven drying at 80 °C to a constant weight. The panicles were hand threshed, and the filled spikelets were separated from the unfilled spikelets by submerging the spikelets in tap water, then half-filled and empty spikelets were separated by seed wind machine (FJ-1, China). Subsequently, three 30 g subsamples of filled spikelets, 15 g subsamples of half-filled spikelets, and 2 g subsamples of empty spikelets were collected to count the number of spikelets. The dry weights of the rachis and filled, half-filled and empty spikelets (unfilled spikelets) were determined after oven drying at 80 °C to a constant weight. The panicles m−2, spikelets per panicle, total spikelets m−2, 1000-grain weight, and harvest index were all calculated. Total dry weight (TDW) was calculated by summing the total dry matter of straw, rachis, filled and unfilled spikelets. Harvest index was calculated as the percentage of grain yield to the aboveground total biomass.

Radiation interception and use efficiency

The climate data (temperature and solar radiation) were collected from the weather station located within 2 km from the experimental site. A datalogger (CR800, Campbell Scientific Inc., Logan, Utah, USA) was used as the measurement and control module. A silicon pyranometer (LI-200, LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) and temperature/RH probe (HMP45C, Vaisala Inc., Helsinki, Finland) were used to measure total solar radiation and temperature, respectively. The total incident radiation were summation of daily global solar radiations from transplanting to maturity.

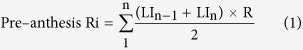

The canopy radiation interception (LI) was measured from transplant to heading in 2013 and 2014. LI was not measured during grain filling because of the occurrence of lodging. The measurements were performed between 1100 and 1300 h on clear-sky days at an interval of 7–15 days during the growing season with a line ceptometer (AccuPAR LP-80, Decagon Devices Inc., Pullman, WA, USA). In each plot, the light intensity inside the canopy was measured by placing the light bar in the middle of two rows and at approximately 5 cm above the water surface. The light intensity was then recorded above the canopy. In total, six measurements were performed in each plot, with three measurements performed in wider rows and three performed in narrower rows. The LI was calculated as the percentage of light intercepted by the canopy (light intensity above the canopy-light intensity below the canopy)/light intensity above the canopy39. The intercepted radiation during each growing period was calculated using the average LI and accumulated global radiation during the growing period. The intercepted global radiation from transplanting to heading (Ri) was the summation of intercepted global radiation during each growing periods as in Equation 1:

|

where n represents the time when LI was measured and R represents total global solar radiation during the period between two consecutive measurements of LI. LI at transplanting (LI0) was assumed to be zero.

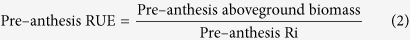

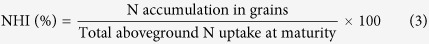

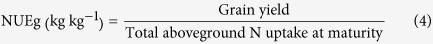

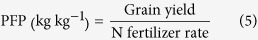

Radiation use efficiency for intercepted global radiation from transplanting to heading (pre-anthesis RUE) was calculated as the ratio of aboveground total dry weight at heading relative to total intercepted global radiation based on Equation 263.

|

Nitrogen uptake and use efficiency

At maturity, after measurement of yield components and biomass from 12-hill samples, dry matter of each plant part [stem plus leaf (straw), filled grains, and unfilled grains plus rachis] was ground to powder to measure N concentration with Elementar vario MAX CNS/CN (Elementar Trading Co., Ltd, Germany). The total aboveground N uptake was then calculated as the product of the N concentration and dry weight of each aboveground part. Nitrogen harvest index (NHI) was calculated as the ratio of grain N content to total aboveground N uptake according to Equation 3. Nitrogen use efficiency for grain production (NUEg) was calculated as the ratio of grain yield over total aboveground N uptake according to Equation 4. Partial factor productivity of applied nitrogen fertilizer (PFP) was calculated as the ratio of grain yield to the fertilizer N input according to Equation 5.

|

|

|

Data analysis

An analysis of variance was performed with Statistix 8.0, and the mean values were compared based on the least significant difference (LSD) test at a 0.05 probability level. All of the figures were constructed and the regression analysis were performed using SigmaPlot 12.5.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhu, G. et al. Genetic Improvements in Rice Yield and Concomitant Increases in Radiation- and Nitrogen-Use Efficiency in Middle Reaches of Yangtze River. Sci. Rep. 6, 21049; doi: 10.1038/srep21049 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University of China (IRT1247), the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities in China (the 111 Project no. B14032), and the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest of China from the Ministry of Agriculture (No. 201203096).

Footnotes

Author Contributions G.Z. was responsible for all of the experimental work, and took joint responsibility with F.W. for writing the manuscript and drawing the figures. S.P. was the principal investigator and laboratory leader, and responsible for the experimental design and reviewing final manuscript. J.H. was responsible for analyzing the data and reviewing final manuscript. K.C. and L.N. were responsible for reviewing the final manuscript. F.W. was responsible for analyzing the data, writing the manuscript and drawing the figures with G.Z.

References

- Ray D., Mueller N., West P. & Foley J. Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. PLOS ONE 8, e66428 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D., Balzer C., Hill J. & Befort B. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20260–20264 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfray H. et al. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray D., Ramankutty N., Mueller N., West P. & Foley J. Recent patterns of crop yield growth and stagnation. Nat. Commun. 3, 10.1038/ncomms2296 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. et al. Producing more grain with lower environmental costs. Nature 514, 486–489 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S., Marshall-Colon A. & Zhu X. Meeting the global food demand of the future by engineering crop photosynthesis and yield potential. Cell 161, 56–66 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khush G. Green revolution: the way forward. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 816–822 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L. Increasing yield potential in rice by exploitation of heterosis in Hybrid rice technology: New developments and future prospects (ed. Virmani S.) 1–6 (International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Philippines, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- Cassman K. Ecological intensification of cereal production systems: yield potential, soil quality, and precision agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5952–5959 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair T., Purcell L. & Sneller C. Crop transformation and the challenge to increase yield potential. Trends Plant Sci. 9, 70–75 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S., Khush G., Virk P., Tang Q. & Zou Y. Progress in ideotype breeding to increase rice yield potential. Field Crops Res. 108, 32–38 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S., Quick W. & Furbank R. The development of C4 rice: current progress and future challenges. Science 336, 1671–1672 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S., Cassman K., Virmani S., Sheehy J. & Khush G. Yield potential trends of tropical rice since the release of IR8 and the challenge of increasing rice yield potential. Crop Sci. 39, 1552–1559 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Austin R. et al. Genetic improvements in winter wheat yields since 1900 and associated physiological changes. J. Agric. Sci. Camb. 94, 675–689 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Tollenaar M. Genetic improvement in grain yield of commercial maize hybrids grown in Ontario from 1959 to 1988. Crop Sci. 29, 1365–1371 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Peng S. et al. Grain yield of rice cultivars and lines developed in the Phillipines since 1966. Crop Sci. 40, 307–314 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Koester R., Skoneczka J., Cary T., Diers B. & Ainsworth E. Historical gains in soybean (Glycine max Merr.) seed yield are driven by linear increases in light interception, energy conversion, and partitioning efficiencies. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 3311–3321 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabien R., Samonte S. & McClung A. Forty-eight years of rice improvement in Texas since the release of cultivar Bluebonnet in 1944. Crop Sci. 48, 2097–2106 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Breseghello F. et al. Results of 25 years of upland rice breeding in Brazil. Crop Sci. 51, 914–923 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Huang Y. & Zhang W. Changes in rice yield in China since 1980 associated with cultivar improvement, climate and crop management. Field Crops Res. 136, 65–75 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Wang C., Ren G., Zhao Y. & Linderholm H. The relative contribution of climate and cultivar renewal to shaping rice yields in China since 1981. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 120, 1–9 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. et al. Changes in agronomic traits of indica hybrid rice during genetic improvement. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 24, 157–161 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. et al. Changes of some agronomic traits in japonica rice varieties during forty-seven years genetic improvement in Jilin province, China. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 21, 507–512 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Long S., Zhu X., Naidu S. & Ort D. Can improvement in photosynthesis increase crop yields? Plant Cell Environ. 29, 315–330 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Long S. & Ort D. Improving photosynthetic efficiency for greater yield. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 235–261 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambavaram M. et al. Coordinated regulation of photosynthesis in rice increased yield and tolerance to environment stress. Nat. Commun. 10.1038/ncomms6302 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Occhialini A., Andralojc P., Parry M. & Hanson M. A faster Rubisco with potential to increase photosynthesis in crops. Nature 513, 547–550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slafer G., Andrade F. & Satorre E. Genetic-improvement effects on pre-anthesis physiological attributes related to wheat grain yield. Field Crops Res. 23, 255–263 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Calderini D., Dreccer M. & Slafer G. Consequences of breeding on biomass, radiation interception and radiation-use efficiency in wheat. Field Crops Res. 52, 271–281 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Shearman V., Sylvester-Bradley R., Scott R. & Foulkes M. Physiological processes associated with wheat yield progress in the UK. Crop Sci. 45, 175–185 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair T. & Horie T. Leaf nitrogen, photosynthesis, and crop radiation use efficiency: a review. Crop Sci. 29, 90–98 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Monasterio I., Sayre K., Rajaram S. & Mcmahon M. Genetic progress in wheat yield and nitrogen use efficiency under four nitrogen rates. Crop Sci. 37, 898–904 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Ciampitti I. & Vyn T. Physiological perspectives of changes over time in maize yield dependency on nitrogen uptake and associated nitrogen efficiencies: a review. Crop Sci. 53, 366–377 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Rochester I. & Constable G. Improvements in nutrient uptake and nutrient use-efficiency in cotton cultivars released between 1973 and 2006. Field Crops Res. 173, 14–21 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Ju C. et al. Grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency of mid-season indica rice cultivars applied at different decades. Acta Agron. Sin. 41, 422–431 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Peng S. et al. The importance of maintenance breeding: a case study of the first miracle rice variety-IR8. Field Crops Res. 119, 342–347 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S. Physiological aspects of grain yield. Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. 23, 437–464. (1972). [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P. The genes of the green revolution. Trends Genet. 19, 5–9 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L. in Rice research for food security and poverty alleviation (eds Peng S. et al.) Ch. 1, 143–149 (IRRI, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda E., Ookawa T. & Ishihara K. Analysis on difference of dry matter production between rice cultivars with different plant height in relation to gas diffusion inside stands. Jpn, J. Crop. Sci. 58, 374–382 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Murchie E., Hubbart S., Chen Y., Peng S. & Horton P. Acclimation of rice photosynthesis to irradiance under field conditions. Plant Physiol. 130, 1999–2010 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith J. Climate and the efficiency of crop production in Britain. Philos. T. R. Soc. B. 281, 277–294 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair T. & Muchow R. Radiation use efficiency. Adv. Agron. 65, 215–265 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Hubbart S., Peng S., Horton P., Chen Y. & Murchie E. Trends in leaf photosynthesis in historical rice varieties developed in the Philippines since 1966. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 3429–3438 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H. & Ishii R. Cultivar differences in leaf photosynthesis of rice bred in Japan. Photosynth. Res. 32, 139–146 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. & Kokubun M. Historical changes in grain yield and photosynthetic rate of rice cultivars released in the 20th century in Tohoku region. Plant Prod. Sci. 7, 36–44 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Murchie E., Pinto M. & Horton P. Agriculture and the new challenges for photosynthesis research. New Phytol. 181, 532–552 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araus J., Reynolds M. & Acedevo E. Leaf structure, leaf posture, growth, grain yield and carbon isotope discrimination in wheat. Crop Sci. 33, 1273–1279 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Innes P. & Blackwell R. Some effects of leaf posture on the yield and water economy of winter wheat. J. Agric. Sci. (Cambridge) 101, 367–376 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Murchie E. et al. Are there associations between grain-filling rate and photosynthesis in the flag leaves of field-grown rice? J. Exp. Bot. 53, 2217–2224 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. Yield potential and radiation use efficiency of “super” hybrid rice grown under subtropical conditions. Field Crop Res. 114, 91–98 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Katsura K. et al. The high yield of irrigated rice in Yunnan, China ‘A cross-location analysis’. Field Crop Res. 107, 1–11 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Slattery R., Ainsworth E. & Ort D. A meta-analysis of responses of canopy photosynthetic conversion efficiency to environmental factors revearls major causes of yield gap. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 3723–3733 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S. et al. Strategies for overcoming low agronomic nitrogen use efficiency in irrigated rice systems in China. Field Crops Res. 96, 37–47 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Rochester I. & Constable G. Improvements in nutrient uptake and nutrient use-efficiency in cotton cultivars released between 1973 and 2006. Field Crops Res. 173, 14–21 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Reich P., Tjoelker M., Machado J. & Oleksyn J. Universal scaling of repiratory metabolism, size and nitrogen in plants. Nature 439, 457–461 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H., Horie T. & Shiraiwa T. A model explaining genotypic and environmental variation of rice spikelet number per unit area measured by cross-location experiments in Asia. Field Crops Res. 97, 337–343 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Kamiji Y., Yoshida H., Palta J., Sakuratani T. & Shiraiwa T. N applications that increase plant N during panicle development are highly effective in increasing spikelet number in rice. Field Crops Res. 122, 242–247 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Hirel B. et al. Towards a better understanding of the genetic and physiological basis for nitrogen use efficiency in maize. Plant Physiol. 125, 1258–1270 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara M. et al. Mapping of QTLs associated with cytosolic glutamine synthetase and NADH-glutamate synthase in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1209–1217 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. et al. Natural variation at the DEP1 locus enhances grain yield in rice. Nat. Genet. 41, 494–497 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H. et al. Heterotrimeric G proteins regulate nitrogen-use efficiency in rice. Nat. Genet. 46, 652–657 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plénet D., Mollier A. & Pellerin S. Growth analysis of maize field crops under phosphorus deficiency. II. Radiation-use efficiency, biomass accumulation and yield components. Plant Soil 224, 259–272 (2000). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.