Abstract

Spin defects in wide-band gap semiconductors are promising systems for the realization of quantum bits, or qubits, in solid-state environments. To date, defect qubits have only been realized in materials with strong covalent bonds. Here, we introduce a strain-driven scheme to rationally design defect spins in functional ionic crystals, which may operate as potential qubits. In particular, using a combination of state-of-the-art ab-initio calculations based on hybrid density functional and many-body perturbation theory, we predicted that the negatively charged nitrogen vacancy center in piezoelectric aluminum nitride exhibits spin-triplet ground states under realistic uni- and bi-axial strain conditions; such states may be harnessed for the realization of qubits. The strain-driven strategy adopted here can be readily extended to a wide range of point defects in other wide-band gap semiconductors, paving the way to controlling the spin properties of defects in ionic systems for potential spintronic technologies.

The idea of realizing and harnessing coherent quantum bits in scalable solid-state environments has attracted widespread attention in the past decade1. One of the milestones in the field has been the coherent manipulation of the single nitrogen-vacancy (NV) defect spin in diamond2,3, opening a new era for using atom-like point defects in crystals as solid-state qubits4,5. However, inherent difficulties in growing and controlling the lattice of C diamond pose severe limitations to the use of the NV center for scalable quantum technologies, begging the question of whether analogs to this defect exist or can be engineered in other technologically mature materials6,7,8,9,10, for examples III-V crystals. Exploration of quantum defect spins in functional ionic crystals such as, e.g. w-AlN, would potentially lead to new opportunities in scalable quantum technologies, including the realization of strongly-coupled spin-mechanical resonator hybrid quantum systems11,12,13. Indeed, the piezoelectric properties of w-AlN make it an ideal system for measuring and controlling the vibrational motion of the lattice14,15 and may offer a variety of control schemes for quantum spins8,13. The strong spontaneous polarization in w-AlN combined with advanced hetero-structuring and band-gap engineering techniques could add flexibility in designing device functionalities15. Interestingly, w-AlN has recently gained significant attention as an opto-mechanical system16,17, making it attractive as a new host crystal for quantum defect spins.

A key step towards building hybrid quantum systems in ionic crystals, and in particular in aluminum nitride, is the identification of localized spin-triplet states akin to the NV center in diamond6. Within a crystalline environment, the spin sublevels of a spin-triplet state may be split even in the absence of an external magnetic field and they can be chosen to function as a quantum bit3. For optical addressability3, the defect center should possess excited spin-triplet states, which can lead to spin-selective decays. These conditions are, however, challenging to realize in ionic crystals for several reasons. In an ionic solid, the energy of defect states derived from dangling bonds is usually close to either the conduction or the valence band edge and, in many cases it may be in strong resonance with that of the bulk band edges6. In the case of w-AlN, another critical constraint stems from doping: this material is naturally n-type, similar to several other nitrides18,19,20, and attaining stable p-type doping is extremely challenging21,22,23,24,25, effectively constraining the search for a defect qubit to n-type w-AlN.

Here, using first-principles calculations26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 we proposed a strain-driven strategy to design stable spin defects in ionic crystals; in particular, we identified the strain conditions leading to the stabilization of localized spin-triplet defect states in w-AlN. We found that by applying moderate uni- and bi-axial strain to the host lattice in the presence of negatively charged N vacancies, we could stabilize spin-triplet states, which are well-localized within the fundamental gap of n-type w-AlN. Our calculations also predicted that these defect spins have a number of spin-conserved excited states, which could be used to optically address the spins3, thus making them strong candidates for solid-state implementations of quantum bits in piezoelectric aluminum nitride.

Results

Spin-state and stability of the native defects in w-AlN

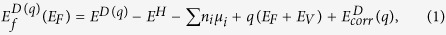

We determined the charge state (q) of a given defect D(q) as a function of the Fermi level (EF) by computing the defect formation energy (EfD(q))37:

|

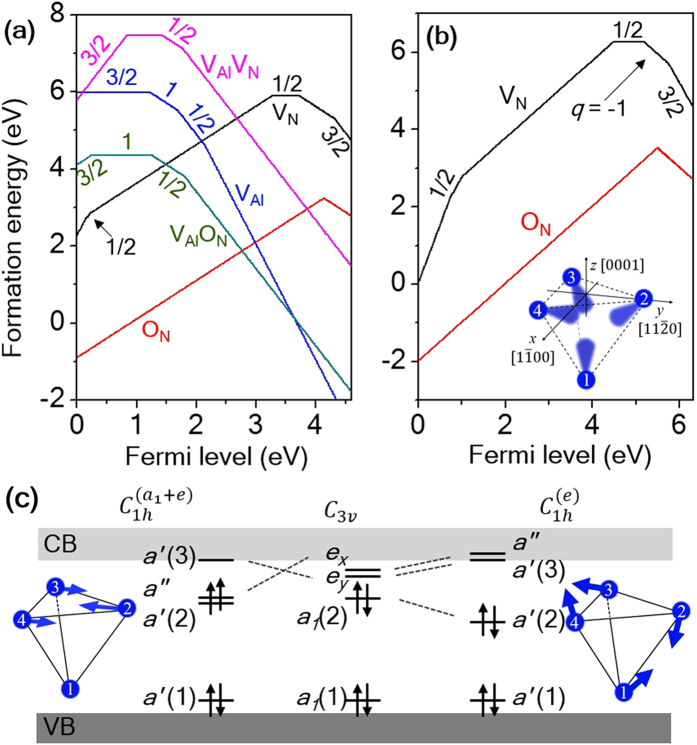

where ED(q) and EH are the total energies computed for supercells with and without a defect, respectively; μi (i = Al, N, O) is the chemical potential and EF is referred to the valence band edge (EV). The last term on the right hand side of equation (1) corrects for artificial electrostatic interactions present in calculations with finite-size supercells and we used a correction scheme developed by Freysoldt, Neugebauer, and Van de Walle38,39. Figure 1(a) reports EfD(q) as a function of the Fermi energy for the native defects of w-AlN as obtained within PBE26. The slope of EfD(q)(EF) yields the charge state of the defect37; a change in slope indicates a change in the charge state of the most stable defect, as a function of the energy of the Fermi level. The spin of each charge state is also indicated in the figure.

Figure 1. Defect formation energy and spin-state of the native defects in w-AlN.

Results obtained within PBE (a) and formation energy of VN and ON computed within PBE0 (b). The lowest-energy effective spin for a given charge state is also shown. The inset of (b) is a schematic representation of the defect-molecule model of VN. Only the nearest neighbor Al atoms (numbered spheres) around the vacancy site and the Al sp3 dangling bonds are shown for clarity. (c) Symmetry-adopted molecular orbitals and spin configurations of VN− under different symmetry environments. The Jahn-Teller distortions for the S = 0 and the S = 1 states are described by the e and a1+e symmetrized displacements, respectively, as schematically shown next to the defect level diagrams.

We first considered Al-vacancy (VAl)-related defects, including complexes with an N vacancy (VAlVN) and an O impurity at the N site (VAlON). Paramagnetic states of cation-vacancy-related defects were previously investigated in III-nitrides, in particular GaN40,41. The origin of the high-spin states of these cation-vacancy-related defects was attributed to the strong electron localization of the N 2p states leading to a large exchange splitting40,41. Furthermore, two recent theoretical papers suggested that the paramagnetic state of cation vacancy – oxygen impurity complexes in AlN and GaN may potentially operate as quantum bits, similar to the NV center in diamond42,43. Consistent with previous calculations40,41,42,43, we found that the VAl-related defects possess a variety of effective electron spins as shown in Fig. 1(a). However, our calculations showed that the paramagnetic ground states associated with VAl-related defects may not be suitable for quantum bit applications for several reasons: those defects with spin states higher than 1/2 are stable in p-doped AlN, which is extremely challenging to achieve20,21; on the other hand, the defects stable in n-type AlN have spin zero. Additionally, the dangling bonds left by the presence of an Al vacancy have mainly N 2p character and their position in energy is very close to EV40,41. In some cases, e.g. for the VAlON complex42,43, the active occupied spin-orbital states are in strong resonance with the valence band due to the large exchange splitting. Therefore, we excluded the VAl-related defects of w-AlN from further consideration in the present work. However we do not exclude VAl-related defects from all possible potential qubit operations. For instance, there may exist excited-state triplets, which may be suitable for quantum operations44.

We now turn to the discussion of anion defects, i.e. VN and ON, from which the main conclusion of our work will be drawn. In this case, we also obtained results using a level of theory higher than PBE and, in particular, we adopted the PBE0 hybrid functional27,28 whose choice is extensively justified in the method section. In addition, we carried out calculations using many-body perturbation theory at the G0W0 level33,34,35. We first note that ON has no effective spins in its ground state since substitutional oxygen either donates an electron to the host (q = +1) or traps an electron (q = −1), leading to a filled DX state45,46,47. On the other hand, we found that VN has S = 1/2 and 3/2 ground states for q = 0 and −2, respectively, in the n-type region, as shown in Fig. 1(a) (PBE results) and (b) (PBE0 results)25,27. These findings indicate that the S = 3/2 state of VN2− might be of potential interest as a defect qubit, but it might be difficult to realize, as highly n-doped w-AlN is difficult to obtain47,48. Interestingly, the VN0 S = 1/2 state has been recently detected using electron paramagnetic resonance18,19. Based on these results, we considered the Fermi level range in the vicinity of the stability region of VN0, which might be accessible in experiments. Interestingly, we found that there is a meta-stable state of VN− with S = 1.

In Fig. 1 we show the defect-molecule model49,50 for VN−, with the four active Al sp3 dangling bonds, {φi,

i = 1 to 4}. The symmetry-adapted molecular orbitals {a1(1), a1(2), ex, ey}51 present in an ideal C3v environment are shown in Fig. 1(c). In such an environment, the ground state configuration of VN− is a1(1)2

a1(2)2, which is a spin-singlet. Additionally, attaining the a1(1)2

a1(2)1

e1 spin-triplet state is possible due to the Hund’s rule coupling. Interestingly, both the S = 0 and S = 1 configurations undergo strong Jahn-Teller (JT)52 distortions (see Fig. 1(c)). A tight-binding model53 with hopping matrix elements, -tij, between states φi and φj provides a simple picture, and for the S=0 configuration it is easy to show that the a’(2) state is pushed down in energy due to the hybridization with the a’(3) state, thus giving rise to an energy gain. On the other hand, the JT distortion for the S = 1 state results in a different orbital ordering as  , and the a′(3) state is pushed above a″, diminishing the hybridization between a′(3) and a′(2). Our calculations also showed that a″ is lowered in energy, thus reducing the energy gap between a′(2) and a″ and the S = 1 state is stabilized according to the Hund’s rule.

, and the a′(3) state is pushed above a″, diminishing the hybridization between a′(3) and a′(2). Our calculations also showed that a″ is lowered in energy, thus reducing the energy gap between a′(2) and a″ and the S = 1 state is stabilized according to the Hund’s rule.

Strain-driven design of defect spins

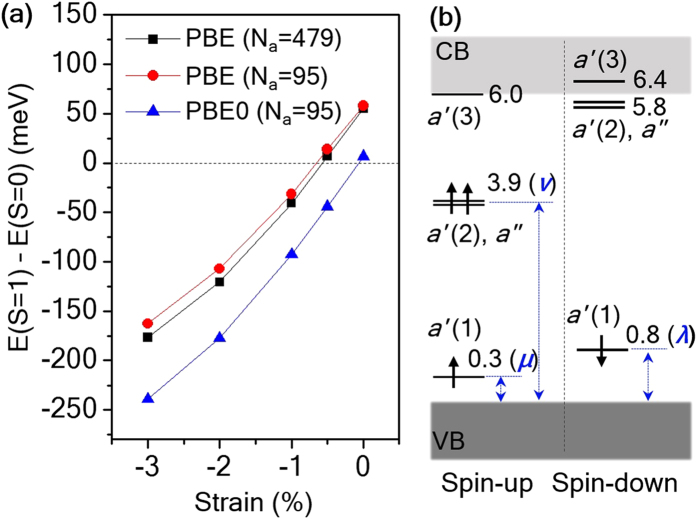

We found that in the absence of any strain the S = 1 state is higher in energy than the S = 0 one by only 55 meV and 7 meV, at the PBE and PBE0 levels of theory, respectively. Note that 7 meV is within the range of our numerical errors, estimated to be ~20 meV/defect at most (see supplementary information). This means that the two spin states (S = 0 and S = 1) of VN− are approximately degenerate in energy within PBE0, although they are associated with two distinct JT-distorted structures, as shown in Fig. 1(c). These results suggest that one may engineer the relative stability of the two spin states by straining the lattice. Strain effects have been extensively explored in nitrides and strain levels up to 4% are considered realistic54,55. Figure 2(a) reports the energy difference between the S = 1 and S = 0 states of VN− as a function of compressive uniaxial strain applied to the host AlN lattice along the [ ] direction, and shows that the S = 1 state is significantly lower in energy than the S = 0 state. Even at a small compressive strain of −3%, the S = 1 state is lower in energy by about 0.25 eV than the S = 0 state within PBE0. This energy difference is well outside our numerical errors (see Supplementary Information) and we expect the energy difference to be representative of the free energy difference as well, since vibrational contributions to the free energy will be almost identical in the two spin configurations (see Supplementary Information). The uniaxial strain effect is twofold. The strained lattice environment is favorable for the S = 1 state as the lattice distortion is compatible with the a1 + e JT mode shown in Fig. 1(c). Furthermore the host lattice expands in the [0001] and [

] direction, and shows that the S = 1 state is significantly lower in energy than the S = 0 state. Even at a small compressive strain of −3%, the S = 1 state is lower in energy by about 0.25 eV than the S = 0 state within PBE0. This energy difference is well outside our numerical errors (see Supplementary Information) and we expect the energy difference to be representative of the free energy difference as well, since vibrational contributions to the free energy will be almost identical in the two spin configurations (see Supplementary Information). The uniaxial strain effect is twofold. The strained lattice environment is favorable for the S = 1 state as the lattice distortion is compatible with the a1 + e JT mode shown in Fig. 1(c). Furthermore the host lattice expands in the [0001] and [ ] directions according to the Poisson’s ratio effect56, which is unfavorable for the S = 0 state because it tends to pull apart the Al3 and Al4 atoms, as well as the Al1 and Al2 atoms. Figure 2(b) reports the defect level diagram of the VN− S = 1 state under −1% uniaxial strain calculated at the G0W0@PBE level, showing the occupied a′(2) and a″ levels being located almost 2 eV below the conduction band minimum (CBM). We also note that in all cases a′(2) and a″ are almost degenerate in energy. As shown in Table 1, the band gap of AlN increases by 0.18 eV within G0W0@PBE, as the uniaxial strain changes from zero to −3%. However, the energy location of the occupied levels a′(2) and a″ does not vary and it remains 3.9 eV above EV (ν in Table 1), indicating that the 3A″ spin-triplet state becomes more localized as the compressive uniaxial strain is increased, a beneficial effect for potential quantum information applications.

] directions according to the Poisson’s ratio effect56, which is unfavorable for the S = 0 state because it tends to pull apart the Al3 and Al4 atoms, as well as the Al1 and Al2 atoms. Figure 2(b) reports the defect level diagram of the VN− S = 1 state under −1% uniaxial strain calculated at the G0W0@PBE level, showing the occupied a′(2) and a″ levels being located almost 2 eV below the conduction band minimum (CBM). We also note that in all cases a′(2) and a″ are almost degenerate in energy. As shown in Table 1, the band gap of AlN increases by 0.18 eV within G0W0@PBE, as the uniaxial strain changes from zero to −3%. However, the energy location of the occupied levels a′(2) and a″ does not vary and it remains 3.9 eV above EV (ν in Table 1), indicating that the 3A″ spin-triplet state becomes more localized as the compressive uniaxial strain is increased, a beneficial effect for potential quantum information applications.

Figure 2. Control of the nitrogen vacancy spin using uniaxial lattice strain.

(a) Total energy difference between the S = 1 and S = 0 states of VN− as a function of the compressive uniaxial strain applied along the [ ] direction. (b) The G0W0@PBE quasi-particle electronic structure of the S = 1 state of VN− under uniaxial strain of −1%. The number next to a defect level is the location of the state referred to EV. Three constants, μ, ν and λ are used to denote the positions of the occupied defect orbitals (see Table 1).

] direction. (b) The G0W0@PBE quasi-particle electronic structure of the S = 1 state of VN− under uniaxial strain of −1%. The number next to a defect level is the location of the state referred to EV. Three constants, μ, ν and λ are used to denote the positions of the occupied defect orbitals (see Table 1).

Table 1. Computed electronic properties of the VN − S = 1 state in w-AlN under the uniaxial and biaxial strain discussed in the main text, including the band gap within G0W0@PBE, the location of the occupied defect orbitals referred to EV in G0W0@PBE (μ,ν,λ shown in Figs 2(b) and 3(b)).

| Strain | Band gap (eV) | Defect orbitals (eV) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ | ν | λ | ||

| Strain-free | 5.94 | 0.36 | 3.90 | 0.73 |

| Uniaxial, -1% | 6.01 | 0.34 | 3.91 | 0.77 |

| Uniaxial, -2% | 6.11 | 0.47 | 3.93 | 0.83 |

| Uniaxial, -3% | 6.12 | 0.42 | 3.89 | 0.80 |

| Biaxial, 3% | 5.35 | 0.30 | 3.55 | 0.66 |

| Biaxial, 4% | 5.10 | 0.20 | 3.42 | 0.59 |

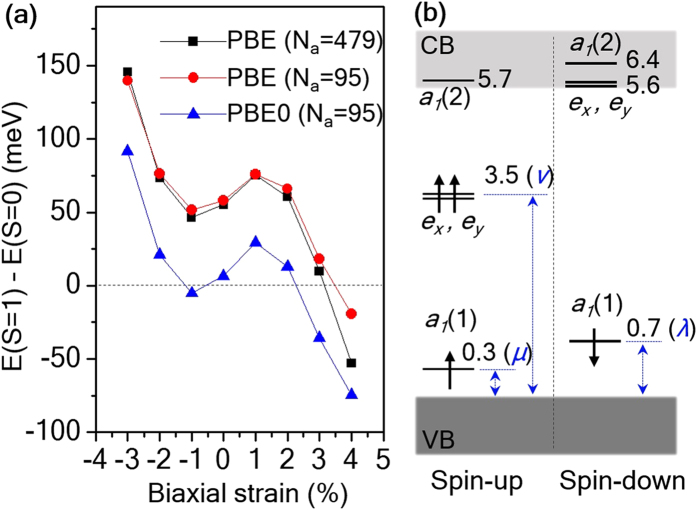

We further explored the possible stability of the S = 1 VN− defect by considering biaxial strain. Figure 3(a) reports the energy difference between the S = 1 and S = 0 states of VN− as a function of biaxial strain applied in the (0001) plane, showing the stabilization of the S = 1 state above 3% strain, within the PBE0 approximation. Under 4% biaxial strain, the S = 1 state is lower in energy by 80 meV than the S = 0 state in PBE0, a result again outside the numerical errors and possible temperature effects (see Supplementary Information). We note that under the biaxial strain considered in Fig. 3(a), the lowest-energy geometry for the S = 0 state is again the C1h(e) JT-distorted structure, with the same orbital ordering shown in Fig. 1(c). However, an increase of biaxial strain to 2% induces a structural transition in the S = 1 state of VN−, and the defect symmetry changes from C1h to C3v. Moreover, the structural transition is accompanied by an a1-type displacement, in which Al4 (see Fig. 1(b)) is moved out of the (0001) plane and up in the z-direction, for example by 0.3 Å at 3% biaxial strain. Let us consider a tight-binding model in the C3v symmetry. The orbital energy of the e-states and the a1(2) state are  and

and  , respectively; here,

, respectively; here,  (= t23 = t34 = t24) and

(= t23 = t34 = t24) and  (= t12 = t13 = t14) are the in-plane and out-of-plane hopping constants, which are decreased and increased, respectively, under tensile biaxial strain. Therefore, application of such strain could reverse the orbital order between ex,y and a1(2) in VN− beyond a certain critical strain level and lead to the formation of a 3A2 S = 1 spin-triplet state, according to Hund’s rule. Figure 3(b) reports the G0W0 quasi-particle electronic structure of the S = 1 state of VN− under 3% biaxial strain, showing the doubly degenerate e-states with two spin-up electrons localized in the band gap of w-AlN. We found that the band gap of w-AlN is decreased from 5.94 eV to 5.35 and 5.10 eV under biaxial strain of 3% and 4%, respectively, within the G0W0@PBE approximation (see Table 1). However, in both cases, the e-states are well-localized and located deep in the gap, 1.8 eV (3% strain) and 1.7 eV (4% strain) below the CBM, within G0W0@PBE.

(= t12 = t13 = t14) are the in-plane and out-of-plane hopping constants, which are decreased and increased, respectively, under tensile biaxial strain. Therefore, application of such strain could reverse the orbital order between ex,y and a1(2) in VN− beyond a certain critical strain level and lead to the formation of a 3A2 S = 1 spin-triplet state, according to Hund’s rule. Figure 3(b) reports the G0W0 quasi-particle electronic structure of the S = 1 state of VN− under 3% biaxial strain, showing the doubly degenerate e-states with two spin-up electrons localized in the band gap of w-AlN. We found that the band gap of w-AlN is decreased from 5.94 eV to 5.35 and 5.10 eV under biaxial strain of 3% and 4%, respectively, within the G0W0@PBE approximation (see Table 1). However, in both cases, the e-states are well-localized and located deep in the gap, 1.8 eV (3% strain) and 1.7 eV (4% strain) below the CBM, within G0W0@PBE.

Figure 3. Control of the nitrogen vacancy spin using biaxial lattice strain.

(a) Total energy difference between the S = 1 and S = 0 state of VN− as a function of the biaxial strain applied in the (0001) plane. The local defect geometry of the S = 0 state maintains a C1h(e) symmetry, as shown in Fig. 1(c), while that of the S = 1 state changes from C1h(a1+e) to C3v for biaxial strain larger than 2%. (b) The G0W0@PBE quasi-particle electronic structure of the S = 1 state of VN− under 3% biaxial strain. The number next to a defect level is the location of the state referred to EV. Three constants, μ, ν, and λ are used to denote the positions of the occupied defect orbitals (see Table 1).

Hyperfine coupling between the VN − defect spin and Al nuclear spins

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)57 is a powerful experimental technique to detect and identify paramagnetic impurities in solids. EPR measurements yield hyperfine parameters, which are mainly determined by the interaction between an impurity’s electron spin and the surrounding nuclear spins, thus these measurements play a key role in the identification of point-like paramagnetic impurities in solids57. Son and co-workers resolved the detailed hyperfine structure of an electron spin-1/2 in w-AlN, mostly interacting with four 27Al nuclei (nuclear spin I = 5/2, 100% natural abundance), and they identified its origin to be VN0 with the help of ab-initio density functional calculations18. In Table 2, we report the computed principal values of the hyperfine tensor of VN0 and we compare them with the previous theoretical and experimental data. Our results are in good agreement with all the previous results, supporting the interpretation of the resolved hyperfine structure being derived from VN0.

Table 2. Computed principal values (in mT) of the hyperfine tensors of VN0 in w-AlN at the PBE level of theory, compared to previous theoretical and experimental results18. The four nearest 27Al (I = 5/2, 100% natural abundance) of VN0 shown in Fig. 1 are considered. The calculated principal values include core polarization (CP) effects, also reported in the table.

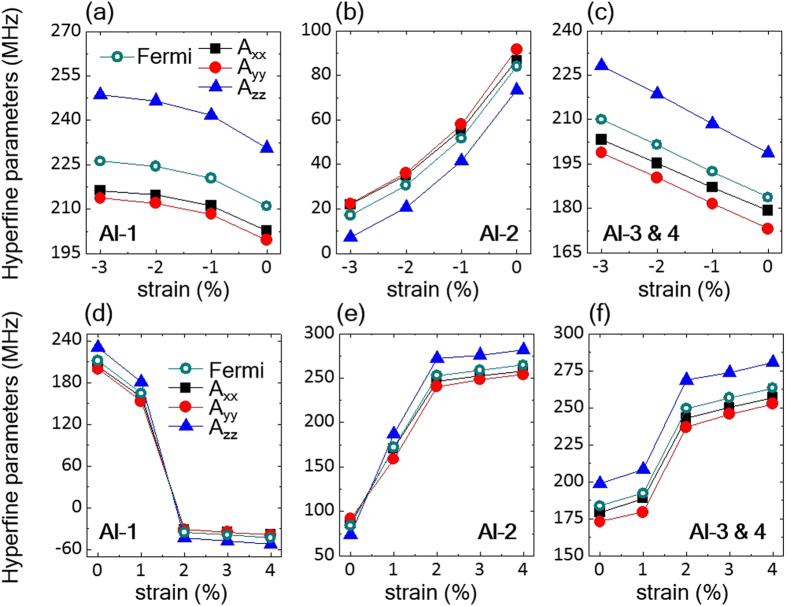

Similar to VN0 in w-AlN, the VN−1 electron spin S = 1 may also interact with the nearest four Al atoms (Al1-4 shown in Fig. 1). We calculated the principal values of the hyperfine tensor of VN− (S = 1) as a function of strain and the results are reported in Fig. 4. Interestingly, the hyperfine parameters exhibit high sensitivity to the applied strain. For the uniaxial case, the hyperfine parameters (Axx, Ayy, and Azz) for Al2 decrease by −75 MHz as the compressive uniaxial strain is increased from 0 to −3%, while those of Al1,3,4 increase. To understand this trend, we show in Fig. 4 the isotropic Fermi contact term as a function of strain along with the hyperfine parameters. We found that the Fermi contact term, which is mainly determined by the electron spin density localized at the corresponding Al site, is mostly responsible for the change of the hyperfine parameters as a function of strain. Figure 4(a–c) indicate that as a result of uniaxial strain in the VN− S = 1 state the spin density is transferred from Al2 to the other Al atoms.

Figure 4. Hyperfine parameters of the VN− spin.

Principal values (in MHz) of the hyperfine tensors and Fermi contact terms for interaction between the VN− electronic spin (S = 1) with the nearest four 27Al nuclei as a function of the uniaxial (a–c) and biaxial (d–f) strains. The four 27Al nuclei (Al1 to Al4) can be seen in Fig. 1. Note that the applied uniaxial strain and the biaxial strain are compressive (negative value) along the [ ] direction and tensile (positive value) in the (0001) plane, respectively. The local defect geometry of the S = 1 state changes from C1h(a1+e) to C3v for biaxial strain larger than 2%, inducing the drastic change in the hyperfine parameters.

] direction and tensile (positive value) in the (0001) plane, respectively. The local defect geometry of the S = 1 state changes from C1h(a1+e) to C3v for biaxial strain larger than 2%, inducing the drastic change in the hyperfine parameters.

Interestingly, the hyperfine parameters as functions of biaxial strain show a more drastic change. The hyperfine parameters for Al1 decrease by more than 250 MHz and become negative while those of the other basal Al nuclei (Al2–4) significantly increase. This is due to the structural transition of the defect geometry from C1h to C3v beyond the 2% biaxial strain, as previously discussed. As a result of the transition, beyond 2% strain the Al2, Al3, and Al4 nuclei become symmetrically equivalent and hence their hyperfine parameters become equal, as shown in Fig. (e,f). The negative hyperfine parameters of Al1 are due to the negative spin density localized near the Al1 atom, which makes the Fermi contact term negative. Before the structural transition occurs, the spin density is distributed almost equally over the four nearest Al nuclei as it is derived from the a′(2) and a″ orbitals in the C1h symmetry. The structural transition to C3v induces, however, a change in the orbital ordering and the spin density is derived from the ex and ey orbitals, which are mainly localized at the basal plane of Al2, Al3, and Al4, leading to increased Fermi contact terms as shown in Fig. 4 (e,f).

Spin-conserved intra-defect excitations in nitrogen vacancy spins

One of the most important properties of the NV center in diamond is the single-spin optical addressability, which relies on the presence of an excited 3E spin-triplet state and its spin-selective decay3. Similar to the diamond NV center, we found that in w-AlN the atomic configuration in which the negatively charged N vacancy has a S = 1 ground state also exhibits S = 1 excited states; hence these states could be obtained by a spin-conserving optical excitation from an occupied defect orbital to an empty defect orbital, as shown in Figs 2(b) and 3(b). Some of the empty defect levels are located slightly above the CBM. We note, however, that the lowest-lying empty defect-orbitals are not in resonance with the CBM; they remain localized, as shown by their dispersion-less character in our computed band structure (not shown) due to the following reasons. The lowest conduction band of w-AlN is a single parabolic band centered at Γ. The next available conduction states appear close the K and L points and they are located at 0.9 and 1.1 eV above the CBM, respectively, according to previous GW calculations58, and consistent with our GW results. Furthermore we found that the CBM mainly exhibits a nitrogen p character, leading to a negligible hybridization with the aluminum dangling bonds created by the VN− defect.

The ZPL was obtained by carrying out calculations of total energy differences (ΔSCF calculations) within the PBE and PBE0 approximation59,60. We first describe possible intra-defect spin-conserving excitation in the spin-down channel, which may be similar to the excitation scheme of the NV center in diamond60. In the case of uniaxial strain, we promoted an electron from a′(1) to a′(2) and the resulting configuration corresponds to the optically excited 3A″ spin-triplet state. The ZPL is rather insensitive to the amount of uniaxial strain, up to 3%, and it is calculated to be ~3.2 eV within PBE. A similar excitation for VN− under biaxial strain, shown in Fig. 3(b), corresponds to a transition to the excited 3E spin-triplet state; for the ZPL we found 3.35 and 3.25 eV under 3% and 4% biaxial strain, respectively within PBE. We note, however, that these near ultra-violet excitations may lead to photo-ionization of VN− to VN0 considering the corresponding (0/−1) charge transition level is about 1.1 eV below the conduction band edge, as shown in Fig. 1(b). In the spin-up channel, however, the ZPLs from a″ to a′(3) under uniaxial strain, and from e to a1(2) under biaxial strain, are expected to be at much lower energies, in the near infrared range. For these cases, we used the PBE0 hybrid functional to better estimate the ZPLs60. We find that the spin-up ZPLs are 0.83 eV and 0.89 eV for −1% uniaxial strain and 3% biaxial strain, respectively.

Discussion

We proposed a strain-driven defect design scheme to obtain point defects with localized spin-triplet ground states for implementation of spin qubits in piezoelectric aluminum nitride. We found that negatively charged nitrogen vacancies exhibit localized spin-triplet states in n-type aluminum nitride under realistic strain conditions. Nitrogen vacancies are naturally incorporated in aluminum nitride during crystal growth and they are known to be the main source of the intrinsic n-type behavior of aluminum nitride18,19,20,21, thus making the nitrogen vacancy spins easily amenable to experimental investigations18,19. Extra n-type doping control might be achievable by introducing substitutional oxygen impurities (ON) during crystal growth24. As shown in Fig. 1(a,b), ON can donate electrons in the region where VN0 is stable and provide the extra charge necessary to form VN−.

In addition to nitrogen vacancies, VAl-related defects are also commonly observed in experiments22,23. Our calculations showed that such defects could in principle introduce a variety of electron spins in the host lattice, which would make it difficult to isolate a single defect spin for qubit applications. However, as shown in Fig. 1(a), the VAl-related defects are magnetically passivated (i.e. S = 0) in the stability region of VN−, thus allowing for the VN− spins to be easily isolated for qubit applications.

We showed that both the S = 0 and S = 1 configurations of VN− undergo static Jahn-Teller (JT)52 distortions as shown Fig. 1(c) and the relative stability of the S = 0 and S = 1 states can be controlled by applying a uniaxial or biaxial strain to the host lattice. Regarding possible temperature effects on the relative stability under strain, dynamic Jahn-Teller effect52 might be an important factor to be considered in addition to the vibrational entropy effect discussed in the Supplementary Material. We also note that potential dynamic Jahn-Teller effects at elevated temperature might be strain-dependent, as we found the defect structure and its lattice environment change significantly in response to external strain perturbations. An investigation of potential dynamic Jahn-Teller effects will be the subject of future studies.

We also showed that excited spin-triplet states are present for negatively charged nitrogen vacancies and these states may play an important role in potential optical manipulations of the vacancy spins. We found that the zero phonon lines for a spin-conserving intra-defect excitation in the spin-down and spin-up channels of the VN− S = 1 state are in the near ultra-violet and in the near infrared range, respectively. We pointed out that the near ultra-violet excitation could lead to photo-ionization of the VN− defect, thus the near infrared excitation may be more suitable for potential optical manipulation of the VN− spin.

The excited triplet may couple to the ground state triplet non-radiatively, similar to the NV center in diamond. We note, however, that additional important issues remain to be considered in order to address the potential optical manipulation of the VN− spin. The optical manipulation of the NV center is based on the spin-orbit-induced spin-selective decay through dark singlet states3. For the VN− system studied here there are open-shell singlet states such as 1A1 or 1E states in the C3v symmetry case and 1A″ in C1h, which may be close in energy to the 3A2 triplet in C3v and the 3A″ triplet in C1h, respectively. These single states may play a role in the optical manipulation of the VN− spin. However, whether these singlet states are positioned in energy between the ground spin triplet and the excited triplet remains to be seen61, as well as whether the spin-orbit interaction between the excited triplet states and the singlet states is sufficiently strong to couple them. We further note that the C3v symmetry of the NV center in diamond is responsible for specific selection rules for the spin-selective decay62. The VN− defect in w-AlN has the C3v symmetry only under the biaxial strain, while it has C1h symmetry under uniaxial strain; such symmetry difference may be an important factor in establishing the potential optical manipulation of the VN− spin.

It is worth mentioning that a number of alternative strain-driven spin manipulation and readout schemes are being actively developed in the literature63,64, and the VN− spins proposed in our study may lead to excellent platforms for the implementation of strain-driven spin control schemes due to the strong piezoelectricity of the host lattice8.

Methods

Ab-initio charged defect calculations

We carried out density functional theory (DFT) calculations with semi-local (PBE26) and hybrid (PBE027,28) functionals, using plane wave basis sets (with a cutoff energy of 75 Ry), norm-conserving pseudopotentials29, and the Quantum Espresso code30. In the case of w-AlN, the self-consistent Hartree-Fock mixing parameter, as derived using the method of Ref. [28], is 24%28, which justifies the use of the PBE0 hybrid functional, whose mixing parameter is defined to be 25% (see below). We examined the most common native defects, which may be easily accessible in experiment (including Al22,23 and N vacancies18,19, O impurities24, and cation-anion defect complexes23,25). To mimic the presence of isolated defects, we employed supercells with 480 and 96-atoms, when using the PBE and PBE0 approximations, respectively, and full geometry optimizations were performed with both functionals. We sampled the Brillouin zone by a 2 × 2 × 2 k-point mesh. Numerical errors in terms of supercell size, k-point sampling and the plane wave cutoff energy were examined and are summarized in the supplementary information. We considered 7 different types of defects and 6 to 7 different charge states for each of them, in addition to 2 to 3 spin multiplicities for each case. For all defect states, total energy minimizations were started from three different initial geometries (with symmetry C3v and C1h) and the state with the lowest energy was selected as the ground state. In total, we explored approximately 300 different defect states.

The use of PBE0 to describe AlN is appropriate, based on our recent work28, as the average electronic dielectric constant of AlN is ~4.128 and we expect the optimal amount of the Hartree-Fock mixing to be 1/4.1 = 24%, which is almost identical to the 25% mixing parameter entering the definition of the PBE0 functional. The accuracy of the PBE0 functional to describe pristine AlN was checked for several properties, which are summarized in Table 3 and are all in excellent agreement with experiment. In particular, using the PBE0 functional we calculated the electronic and static dielectric constants of AlN with a combined finite E-field and Berry phase method65,66. We calculated the electronic dielectric constants to be 4.06 and 4.22 for  and

and  , respectively, to be compared with experimental values of 4.13 ± 0.02 for

, respectively, to be compared with experimental values of 4.13 ± 0.02 for  and 4.27 ± 0.05 for

and 4.27 ± 0.05 for  67. For the static dielectric constants, we calculated

67. For the static dielectric constants, we calculated  and

and to be 7.71 and 8.95, respectively, to be compared with experimental values of 9.18 for

to be 7.71 and 8.95, respectively, to be compared with experimental values of 9.18 for 68 and the result of 8.5 obtained from polycrystalline AlN69. Note that PBE0 accurately describes the anisotropic nature of the dielectric constants of AlN. The accuracy of the PBE0 functional to describe the native defects in AlN was checked by calculating defect formation energies and charge transition levels of the N vacancy and O impurity as shown in Fig. 1(b). Recently, similar results using another hybrid functional (HSE) were reported in Ref. [25]; the authors were able to successfully explain the experimentally observed optical absorption and emission of the defects and we verified that our PBE0 results are in almost perfect agreement with those of Ref. [25].

68 and the result of 8.5 obtained from polycrystalline AlN69. Note that PBE0 accurately describes the anisotropic nature of the dielectric constants of AlN. The accuracy of the PBE0 functional to describe the native defects in AlN was checked by calculating defect formation energies and charge transition levels of the N vacancy and O impurity as shown in Fig. 1(b). Recently, similar results using another hybrid functional (HSE) were reported in Ref. [25]; the authors were able to successfully explain the experimentally observed optical absorption and emission of the defects and we verified that our PBE0 results are in almost perfect agreement with those of Ref. [25].

Table 3. Computed electronic and structural properties of w-AlN using PBE and PBE0 compared to the experimental values, including the lattice constant, the direct band gap (Eg), the crystal field splitting (ΔCF) and the electronic and static dielectric constants.

| Lattice parameters | Electronic properties | Dielectric constants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a(Å) | c/a | u | Eg (eV) | ΔCF(meV) | Electronic ( / / ) ) |

Static ( / / ) ) |

|

| PBE | 3.130 | 1.603 | 0.382 | 4.09 | −201 | 4.42/4.63 | 8.33/9.77 |

| PBE0 | 3.107 | 1.601 | 0.382 | 6.35 | −223 | 4.06/4.22 | 7.71/8.95 |

| Experiment | 3.11036 | 1.60136 | 0.38236 | 6.0–6.336 | −23036 | 4.13 ± 0.0267/4.27 ± 0.0567 | (not known)/9.1868, 8.5 (poly-crystalline)69 |

The zero-phonon line (ZPL) was obtained by carrying out calculations of total energy differences (ΔSCF calculations) within the PBE and PBE0 approximation59,60. We employed 480-atom and 288-atom supercells along with 75 Ry and 65 Ry plane-wave cutoff energies for the PBE and PBE0 calculations, respectively. By using the PBE functional, we checked the numerical error induced by reducing the supercell size from 480 atoms to 288 atoms and the plane-wave cutoff energy from 75Ry to 65Ry to be around 0.05 eV.

First-principles calculations of hyperfine tensors

We carried out calculations of hyperfine tensors between VN spins and nuclear spins in w-AlN at the PBE level of theory. The calculations were performed in two steps. First, we calculated the ground-state wavefunctions for VN using the 480-atom supercell as described in the previous section. Then, we used the gauge-including projector-augmented wave method (GIPAW) of Ref. [70] to calculate the hyperfine tensor, which is comprised of the isotropic Fermi contact term and the anisotropic dipolar coupling term. Numerical convergence in terms of the energy cutoff, the k-point sampling, and the supercell size was checked, with a numerical error in the hyperfine tensor less than 10 MHz. To verify the accuracy of the PBE functional, we calculated the hyperfine parameters of the neutral VN spin (S = 1/2) and compared them to previous theoretical and experimental results18 as shown in Table 2. We found an excellent agreement between our and previous results. In addition, we found that adding core polarization effects71,72 improves the agreement between our results and experiment, thus we included core polarization effects throughout all of our calculations.

Large-scale many-body GW calculations

In order to check the robustness of our predictions, we carried out calculations of quasi-particle energies within the G0W0 approximation31,32, using the Γ point only and 480-atom supercells with defect geometries optimized at the PBE level of theory. GW calculations were performed utilizing a spectral decomposition technique for the dielectric matrix33,34 and an efficient contour deformation technique for frequency integration35, as implemented in the WEST code (www.west-code.org), where the evaluation of virtual electronic states is not required. Calculations carried out with the WEST code started from the results obtained with the semi-local PBE functional and perturbative corrections to the Kohn-Sham eigenvalues were obtained. The massively parallel implementation of the GW method in WEST takes advantage of separable expressions for both the Green’s function (G) and the screened Coulomb interaction (W). The newly developed technique for large-scale GW calculations allowed us to explore defective AlN systems of unprecedented size, containing ~2000 electrons. For the band gap of w-AlN, we obtained 5.94 eV within the G0W0@PBE approximation using our 480-atom supercell with a point defect, which is in very good agreement with the previous G0W0@LDA results of 5.8 eV58 and 6.08 eV73 obtained for the pristine bulk.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Seo, H. et al. Design of defect spins in piezoelectric aluminum nitride for solid-state hybrid quantum technologies. Sci. Rep. 6, 20803; doi: 10.1038/srep20803 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Awschalom for suggesting w-AlN as a new potential host material for quantum defect spins. We also thank William Koehl, Jonathan Skone, Matthew Goldey, Márton Vörös, and Eun-Gook Moon for helpful discussions. HS is primarily supported by the National Science Foundation through the University of Chicago MRSEC under award number DMR-1420709. MG and GG are supported by DOE grant No. DE-FG02-06ER46262. Part of this work (MG) was done at Argonne National Laboratory, supported under U.S. Department of Energy contract DE-AC02-06CH1135. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, resources of the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357, and resources of the University of Chicago Research Computing Center.

Footnotes

Author Contributions H.S. and G.G. designed the research. Most of the calculations were performed by H.S., with contributions from all authors. M.G. implemented the GW many-body perturbation theory in the WEST code. All authors contributed to the analysis and discussion of the data and the writing of the manuscript.

References

- Awschalom D. D., Bassett L. C., Dzurak A. S., Hu E. L. & Petta J. R. Quantum spintronics: engineering and manipulating atom-like spins in semiconductors. Science 339, 1174–1179 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber A. et al. Scanning confocal optical microscopy and magnetic resonance on single defect centers. Science 276, 2012–2014 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Jelezko F. et al. Observation of coherent oscillation of a single nuclear spin and realization of a two-qubit conditional quantum gate. Phys. Rev. Lett 93, 130501 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernien H. et al. Heralded entanglement between solid-state qubits separated by three metres. Nature 497, 86–90 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucsko G. et al. Nanometre-scale thermometry in a living cell. Nature 500, 54–58 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber J. R. et al. Quantum computing with defects. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 107, 8513–8518 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehl W. F., Buckley B. B., Heremans F. J., Calusine G. & Awschalom D. D. Room temperature coherent control of defect spin qubits in silicon carbide. Nature 479, 84–87 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk A. L. et al. Electrically and mechanically tunable electron spins in silicon carbide color centers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 187601 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widmann M. et al. Coherent control of single spins in silicon carbide at room temperature. Nature Mater. 14, 164–168 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christle D. J. et al. Isolated electron spins in silicon carbide with millisecond coherence times. Nature Mater. 14, 160–163 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovartchaiyapong P., Lee K. W., Myers B. A. & Bleszynski Jayich A. C. Dynamic strain-mediated coupling of a single diamond spin to a mechanical resonator. Nat. Commun. 5, 4429 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepesidis K. V., Bennett S. D., Portolan S., Lukin M. D. & Rabl P. Phonon cooling and lasing with nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 88, 064105 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Treutlein P., Genes C., Hammerer K., Poggio M. & Rabl P. Hybrid mechanical systems, in Cavity Optomechanics, ed. by Aspelmeyer M., Kippenberg T. J. & Marquardt F. (Springer, Berlin 2014) p. 327. [Google Scholar]

- Piazzaa G., Felmetsgera V., Muralta P., Olsson R. H. III & Rubya R. Piezoelectric aluminum nitride thin films for microelectromechanical systems. MRS Bulletin 37, 1051–1061 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Egawa T. & Oda O. III-Nitride Based Light Emitting Diodes and Applications, edited by Seong T.-Y., Han J., Amano H. & Morkoc H. (Springer, Berlin, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong C. et al. Aluminum nitride as a new material for chip-scale optomechanics and nonlinear optics. New J. Phys. 14, 095014 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Bochmann J., Vainsencher A., Awschalom D. D. & Cleland A. N. Nanomechanical coupling between microwave and optical photons. Nature Phys. 9, 712–716 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Son N. T. et al. Defects at nitrogen site in electron-irradiated AlN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 242116 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Soltamov V. A. et al. EPR and ODMR defect control in AlN bulk crystals. Phys. Stat. Sol. (c) 10, 449–452 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Buckeridge J. et al. Determination of the nitrogen vacancy as a shallow compensating center in GaN doped with divalent metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 016405 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Liu W. & Niu H. Native defect properties and p-type doping efficiency in group-IIA doped wurtzite AlN. Phys. Rev. B 77, 035201 (2008) [Google Scholar]

- Sedhain A., Du L., Edgar J. H., Lin J. Y. & Jiang H. X. The origin of 2.78 eV emission and yellow coloration in bulk AlN substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 262104 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Mäki J.-M. et al. Identification of the VAl-ON defect complex in AlN single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 84, 081204R (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Bickermann M., Epelbaum B. M. & Winnacker A. Characterization of bulk AlN with low oxygen content. J. Cryst. Growth 269, 432–442 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q., Janotti A., Scheffler M. & Van de Walle C. G. Origins of optical absorption and emission lines in AlN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 111104 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P., Burke K. & Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo C. & Barone V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 6158–6170 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Skone J. H., Govoni M. & Galli G. Self-consistent hybrid functional for condensed systems. Phys. Rev. B 89, 195112 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Troullier N. & Martins J. L., Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. Phys. Rev. B 43, 1993–2006 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannozzi P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedin L. New method for calculating the one-particle Green’s function with application to the electron-gas problem. Phys. Rev. 139, A796–A828 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- Hybertsen M. S. & Louie S. G. First-principles theory of quasiparticles: calculation of band gaps in semiconductors and insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 1418–1421 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H.-V., Pham T. A., Rocca D. & Galli G. Improving accuracy and efficiency of calculations of photoemission spectra within the many-body perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 85, 081101 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Pham T. A., Nguyen H.-V., Rocca D. & Galli G. GW calculations using the spectral decomposition of the dielectric matrix: Verification, validation and comparison of methods. Phys. Rev. B 87, 155148 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Govoni M. & Galli G. Large scale GW calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput., 11, 2680–2696 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinke P. et al. M. Consistent set of band parameters for the group-III nitrides AlN, GaN, and InN. Phys. Rev. B 77, 075202 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Freysoldt C. et al. First-principles calculations for point defects in solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 253–305 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Freysoldt C., Neugebauer J. & Van de Walle C. G. Fully ab initio finite-size corrections for charged-defect supercell calculations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 016402 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komsa H., Rantala T. T. & Pasquarello A. Finite-size supercell correction schemes for charged defect calculations. Phys. Rev. B 86, 045112 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Gohda Y. & Oshiyama A. Stabilization mechanism of vacancies in group-III nitrides: exchange splitting and electron transfer. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 79, 083705 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Dev P., Xue Y. & Zhang P. Defect-induced intrinsic magnetism in wide-gap III nitrides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 117204 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y. et al. A paramagnetic neutral VAlON center in wurtzite AlN for spin qubit application. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 072103 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. et al. Spin-polarization of VGaON center in GaN and its application in spin qubit. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 192401 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. et al. Readout and control of a single nuclear spin with a metastable electron spin ancilla. Nature Nanotech. 8, 487–492 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. H. & Chadi D. J. Stability of deep donor and acceptor centers in GaN, AlN and BN. Phys. Rev. B 55, 12995–13001 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Van de Walle C. G. DX-center formation in wurtzite and zinc-blende AlxGa1−xN. Phys. Rev. B 57, R2033–R2036 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri L., Dunn K., Prawer S. & Ladouceur F., Hybrid functional study of Si and O donors in wurtzite AlN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 122109 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Schulz T. et al. n-type conductivity in sublimation-grown AlN bulk crystals. Phys. Stat. Solidi (RRL) 1, 147–149 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Coulson C. A. & Kearsley M. J. Colour centres in irradiated diamonds. I. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. A 241, 433–454 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- Loubser J. H. N. & van Wyk J. P. Diamond Research (London) (Industrial Diamond Information Bureau, London, 1977), pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lenef A. & Rand S. C. Electronic structure of the N-V center in diamond: theory. Phys. Rev. B 53, 13441–13455 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersuker I. B. The Jahn-Teller Effect (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006) [Google Scholar]

- Harrison W. A. Electronic Structure and the Properties of Solids (Dover Publication Inc., New York, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q., Rinke P., Janotti A., Scheffler M. & Van de Walle C. G. Effects of strain on the band structure of group-III nitrides. Phys. Rev. B 90, 125118 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Jones E. et al. Towards rapid nanoscale measurement of strain in III-nitride heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 231904 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Nye J. F. Physical Properties of Crystals: Their Representation by Tensors and Matrices (Oxford University Press Inc., New York, 1985). [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger A. & Jeschke G. Principles of pulse electron paramagnetic resonance (Oxford University Press Inc., New York, 2001) [Google Scholar]

- Rubio A., Corkill J. L., Cohen M. L., Shirley E. L. & Louie S. G. Quasiparticle band structure of AlN and GaN. Phys. Rev. B 48, 11810–11816 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gali A., Fyta M. & Kaxiras E. Ab initio supercell calculations on nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond: electronic structure and hyperfine tensors. Phys. Rev. B 77, 155206 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Gali A., Janzén E., Deák P., Kresse G. & Kaxiras E. Theory of spin-conserving excitation of the N−V− center in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 186404 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S., Jain M. & Louie S. G. Mechanism for optical initialization of spin in NV− center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 86, 041202 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M. L. et al. State-selective intersystem crossing in nitrogen-vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. B 91, 165201 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQuarrie E. R. et al. Coherent control of a nitrogen-vacancy center spin ensemble with a diamond mechanical resonator. Optica 2, 233–238 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Struck P. R., Wang H. & Burkard G. Nanomechanical readout of a single spin. Phys. Rev. B 89, 045404 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Souza I., Íñiguez J. & Vanderbilt D. First-Principles Approach to Insulators in Finite Electric Fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 117602 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umari P. & Pasquarello A. Ab initio Molecular Dynamics in a Finite Homogeneous Electric Field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 157602 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokhovets S. et al. Determination of the anisotropic dielectric function for wurtzite AlN and GaN by spectroscopic ellipsometry. J. Appl. Phys. 94, 307–312 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Malengreaua F. et al. Epitaxial growth of aluminum nitride layers on Si(111) at high temperature and for different thicknesses. J. of Mater. Res. 12, 175–188 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Akasaki I. & Hashimoto M. Infrared lattice vibration of vapour-grown AlN. Solid State Comm. 5, 851–853 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- Pickard C. J. & Mauri F. All-electron magnetic response with pseudopotentials: NMR chemical shifts. Phys. Rev. B 63, 245101 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Bahramy M. S., Sluiter M. H. F. & Kawazoe Y. Pseudopotential hyperfine calculations through perturbative core-level polarization. Phys. Rev. B 76, 035124 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Filidou V., Ceresoli D., Morton J. J. L. & Giustino F. First-principles investigation of hyperfine interactions for nuclear spin entanglement in photoexcited fullerenes. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115430 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Cociorva D., Aulbur W. G. & Wilkins J. W. Quasiparticle calculations of band offsets at AlN-GaN interfaces. Solid State. Commun. 124, 63–66 (2002). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.