Abstract

Background: Two recent meta-analyses showed decreased red blood cell (RBC) polyunsaturated fatty acids (FA) in schizophrenia and related disorders. However, both these meta-analyses report considerable heterogeneity, probably related to differences in patient samples between studies. Here, we investigated whether variations in RBC FA are associated with psychosis, and thus may be an intermediate phenotype of the disorder. Methods: For the present study, a total of 215 patients (87% outpatients), 187 siblings, and 98 controls were investigated for multiple FA analyses. Based on previous studies, we investigated docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), arachidonic acid (AA), linoleic acid (LA), nervonic acid (NA), and eicasopentaenoic acid (EPA). On an exploratory basis, a large number of additional FA were investigated. Multilevel mixed models were used to compare the FA between the 3 groups. Results: Compared to controls, both patients and siblings showed significantly increased DHA, DPA, AA, and NA. LA was significantly higher in siblings compared to controls. EPA was not significantly different between the 3 groups. Also the exploratory FA were increased in patients and siblings. Conclusions: We found increased RBC FA DHA, DPA, AA, and NA in patients and siblings compared to controls. The direction of change is similar in both patients and siblings, which may suggest a shared environment and/or an intermediate phenotype. Differences between patient samples reflecting stage of disorder, dietary patterns, medication use, and drug abuse are possible modifiers of FA, contributing to the heterogeneity in findings concerning FA in schizophrenia patients.

Key words: Schizophrenia, FA (fatty acid), AA (arachidonic acid), NA (nervonic acid), endophenotype, familial

Introduction

Despite extensive research, the pathophysiology of schizophrenia still remains unclear. At present, the dominant theory on the pathophysiology of schizophrenia is the neurodevelopmental model. During brain development, neuronal maturation and apoptosis interact with environmental influences. The neurodevelopmental theory postulates that schizophrenia symptoms arise when, at the end of puberty, the balance between neuronal proliferation and myelination, on the one hand, and apoptosis, on the other hand, is pathologically altered.1,2 Fatty acids (FA) play an important role in this development.3,4

FA are basic constituents of cell membranes, among which polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) largely determine fluidity, flexibility, and oxidative stress susceptibility.5 An appropriate distribution of FA in the membrane is needed to maintain proper cell metabolism, thereby modulating receptors, ion channels, and cell signalling.6 Moreover, omega-6 and omega-3 PUFA seem particularly important because they are precursors of pro- and anti-inflammatory eicosanoids, respectively, which have been implicated in schizophrenia’s pathophysiology. These notions have led Horrobin et al7 to postulate the “membrane phospholipid hypothesis” of schizophrenia. This hypothesis states that one of the factors contributing to altered neuronal survival and/or functioning in schizophrenia may be inappropriate levels of membrane FA, pointing out a possible biochemical substrate for the neurodevelopmental theory of schizophrenia.

Since Horrobin et al7 postulated this hypothesis, a considerable number of studies have investigated FA in the red blood cell (RBC) membrane, as a proxy for the neuronal membrane. Indeed, 2 recent meta-analyses showed that decreased PUFA are associated with schizophrenia and psychosis spectrum disorders.8,9 The most distinctive findings concerned decreased docosahexaenoic acid (C22:6ω3, DHA), docosapentaenoic acid (C22:5ω3, DPA), and arachidonic acid (C20:4ω6, AA) in patients, compared to healthy controls.

However, both meta-analyses also reported considerable heterogeneity, with respect to both the patient samples, as well as the findings itself. The included relatively small studies differed from one another with respect to stage of the disorder, medication use, and ethnic background of the investigated patients. Although the meta-analyses identified lower PUFA in patients, some studies found higher.10–16

Moreover, as most studies were cross-sectional, it remains unclear whether differences in FA are attributable to medication effects, phase of the disorder, environmental influences, or are intrinsically associated with genetic vulnerability for the disorder.

One way to surpass the potential confounding effects of treatment and chronicity of the disorder is to include healthy family members of patients with schizophrenia and psychosis spectrum disorders. This may lead to identification of FA variations as intermediate phenotypes, potentially suggesting genetically mediated traits that are more prevalent in unaffected relatives of patients compared to the general population. To the best of our knowledge, thus far only one small preliminary study of solely linoleic acid (LA) found a familial tendency of lower concentrations in schizophrenia patients (N = 38) and their first-degree relatives (N = 34) compared to healthy controls.17

Therefore, the objective of our study is to compare RBC FA between a large sample of schizophrenia patients, their relatives, and healthy controls. Based on the aforementioned 2 meta-analyses, we a priori selected DHA, DPA(ω3), AA, and LA and hypothesized that these FA are lower in patients, as well as in their siblings, in comparison to healthy controls.

We added nervonic acid (C24:1w9; NA) and eicasopentaenoic acid (C20:5w3; EPA) to this a priori selection. NA is a major component of the myelin membrane and EPA is—next to, and in competition with AA—a main precursor for anti-inflammatory eicosanoids.6 We hypothesized that these 2 compounds are also lower in patients compared to controls. Finally, a large range of other non-a priori selected FA were analyzed on an exploratory basis.

So the specific research questions are:

1. Are there differences in the a priori selected RBC FA between patients, siblings, and controls and do these differences sustain after controlling for group status differences in potential confounders?

2. Are there differences in other RBC FA between patients, siblings, and controls?

Methods

Participants

The study sample was a subset of the large “Genetic Risk and Outcome of Psychosis” (GROUP) study, in which 1120 patients, 1057 siblings, 665 parents, and 590 controls participated. GROUP is a multisite, longitudinal, naturalistic cohort study examining the 6-year course of patients with nonaffective psychotic disorders and their first-degree family members. The subset comprised of the GROUP subjects for which FA samples were available. Samples for FA were collected as part of an add-on study performed at the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam and its affiliated regional mental health care centers. FA data were collected between April 2005 and October 2008.

Eligible patients for the GROUP project were either inpatients or outpatients and had to fulfill the following criteria: (1) age between 16 and 50 years, (2) meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for a nonaffective psychotic disorder (schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and psychotic disorder not other specified [NOS]), (3) good command of the Dutch language, and (4) able and willing to give written informed consent. Inclusion criteria for siblings were: (1) age between 16 and 50 years, (2) good command of the Dutch language, and (3) able and willing to give written informed consent. Healthy controls were recruited by advertisements and by mailings and had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) age between 16 and 50 years, (2) no lifetime history of psychotic disorder, (3) no first-degree family member with a lifetime psychotic disorder, (4) good command of the Dutch language, and (5) able and willing to give written informed consent. The presence of symptoms and signs of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder or an affective disorder and the severity of psychopathology was assessed in patients, siblings, and healthy controls by the CASH (Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History) which is a standardized clinical interview.18 The exclusion criteria for the main GROUP study are limited to not having command for Dutch language or not willing to give informed consent. This was done to warrant the generalizability of the results. Comorbidity in patients, siblings, and parents was not an exclusion criterion. If a lifetime psychotic disorder was diagnosed among siblings or parents, they were included in the patient group. The only exclusion criterion among healthy controls was a lifetime psychotic disorder or a lifetime psychotic disorder of a first-degree relative (for more detailed information about the GROUP project see Korver et al).19

The study protocol for the GROUP project as a whole, as well as for the FA sampling add-on study, was approved centrally by the Ethical Review Board of the University Medical Center Utrecht and subsequently by local review boards of each participating institute. All participants provided written informed consent.

Measurements

Fatty Acids.

Nonfasting venous blood samples for FA analysis were collected at the participating mental health centers and immediately sent to the Laboratory Genetic Metabolic Diseases (LGMD) of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

FA were analyzed in erythrocytes by capillary gas chromatography in the following manner. Erythrocytes of venous Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) blood were washed 3 times in isotonic saline, counted by routine hemocytometric analysis, and frozen overnight in a 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol-coated eppendorf cup. Fifty microliters of the resulting hemolysate was transmethylated in 1ml 3M HCl by incubating for 4 hours at 90°C in the presence of 10 nmol internal standard; the methyl ester of 18-methylnonadecanoic acid. After cooling, the aqueous layer was extracted in 2ml hexane, and this extract was taken to dryness under nitrogen flow and resuspended in 80 µl of hexane. One microliter of this solution was injected into a Hewlett Packard GC 5890 equipped with an Agilent J&W HP-FFAP, 25 m, 0.20mm, 0.33 µm GC Column and eluting FA methylesters were detected by flame ionization detection. FA concentrations were calculated using the known amount of internal standard and expressed as pmol/106 cells for erythrocytes. These measurements resulted in data for 28 different FA (see table 3 for an overview of all measured FA).

Table 3.

Mean Levels of a Priori and Exploratory FA Between Patients, Siblings, Controls

| Patients (N = 215) | Siblings (N = 187) | Controls (N = 98) | F a | P a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)b | Mean (SD)b | Mean (SD)b | |||

| A priori FA | |||||

| C22:6w3 DHA | 16.4 (5.1) | 17.7 (5.0) | 16.0 (5.5) | 2.46 | .087 |

| C22:5w3 DPA | 9.7 (2.0) | 9.3 (2.2) | 8.5 (2.0) | 6.47 | .002 |

| C20:4w6 AA | 76.4 (11.2) | 77.1 (10.2) | 71.7 (9.6) | 7.98 | <.001 |

| C18:2w6 LA | 64.3 (12.7) | 64.6 (11.5) | 60.8 (9.5) | 2.33 | .098 |

| C24:1w9 NA | 18.1 (3.9) | 18.8 (4.0) | 16.4 (3.4) | 11.06 | <.001 |

| C20:5w3 EPA | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.5) | 1.42 | .243 |

| Exploratory FA c | |||||

| C14:0 | 2.8 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.2) | 0.80 | .450 |

| C16:0 | 148.3 (19.7) | 150.3 (20.1) | 142.5 (17.4) | 3.67 | .026 |

| C18:0 | 100.6 (11.7) | 100.2 (11.6) | 96.2 (11.0) | 4.67 | .010 |

| C20:0 | 2.4 (0.4) | 2.4 (0.4) | 2.3 (0.4) | 3.88 | .021 |

| C22:0 | 8.9 (1.6) | 9.1 (2.7) | 8.5 (1.4) | 4.05 | .018 |

| C24:0 | 20.4 (4.4) | 20.3 (4.3) | 18.8 (4.0) | 5.50 | .004 |

| C18:3w3 | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.3) | 4.09 | .017 |

| C18:4w3 | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.21 | .810 |

| C14:1w5 | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.7) | 1.54 | .215 |

| C20:2w6 | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.19 | .306 |

| C20:3w6 | 9.9 (2.7) | 9.6 (2.2) | 8.8 (2.0) | 4.95 | .008 |

| C22:4w6 | 13.4 (3.2) | 13.8 (3.2) | 12.6 (2.9) | 7.34 | .001 |

| C22:5w6 | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.2 (0.7) | 3.46 | .032 |

| C16:1w7 | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.2) | 1.8 (0.8) | 2.36 | .095 |

| C18:1w7 | 7.1 (1.3) | 7.3 (1.3) | 6.8 (1.1) | 5.27 | .006 |

| C20:1w7 | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.7) | 1.52 | .221 |

| C16:1w9 | 1.0 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.5) | 0.07 | .937 |

| C18:1w9 | 71.3 (10.8) | 72.0 (13.0) | 66.5 (12.8) | 7.48 | .001 |

| C20:1w9 | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.15 | .319 |

| C20:3w9 | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | 2.56 | .078 |

| C22:1w9 | 3.5 (4.5) | 3.2 (2.5) | 3.0 (2.0) | 0.31 | .733 |

| Total FA | 588.8 (70.8) | 593.2 (70.3) | 556.1 (62.1) | 8.60 | <.001 |

| Total AA/Total DHA | 5.1 (1.6) | 4.7 (1.3) | 4.9 (1.6) | 0.55 | .576 |

| Total w6/Total w3 a priori FA |

5.1 (1.2) | 5.0 (1.2) | 5.2 (1.3) | 1.90 | .150 |

| Total w6/Total w3 all FA |

5.8 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.3) | 5.6 (1.6) | 0.17 | .846 |

Note: AA, Arachidonic Acid; BMI, Body Mass Index; DPA, Docosapentaenoic Acid; DHA, Docosahexaenoic Acid; EPA, Eicasopentaenoic Acid; FA, Fatty Acid; IQ, intelligence quotient; LA, linoleic acid.

aAdjusted for gender, IQ, BMI, tobacco use.

bConcentrations of FA are given as picomol/106 erythrocytes.

cSubstitution of nondetectable values with 0.

Recent insights by Mocking et al20 suggested that it may be informative to express FA levels as fractions of the amount of total FA. We, therefore, computed these fractions for the 6 a priori FA, and provide them in a post-hoc analysis.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

A large number of clinical and demographic characteristics were collected as part of the GROUP project. For a detailed description of these characteristics, and of the instruments used, we refer to Korver et al.19 Based on previous FA studies, we selected the following possible confounding or effect-modifying variables: gender, age, cannabis use, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, IQ, duration of illness, age of onset, and type of antipsychotics used (typical vs nontypical antipsychotics).

Statistical Analysis.

Differences between the group status (patient, sibling, and control) in terms of gender, age, ethnicity, IQ, BMI, cannabis use, and tobacco use were assessed with ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Normality of the distribution of the dependent variables was assessed with a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In case of significant deviance of a normal distribution, we used bootstrapping with 2000 bootstrap samples and present the bootstrap estimates of the parameters and SEs. The relation between FA and group status (patient, sibling, control) was investigated with a separate linear mixed-model regression analysis for each FA, with FA as the dependent variable and the categorical variable group status (patient, sibling, control) as the independent variable. The dependence between the data due to family relation (patients and siblings belonging to the same families) was taken into account by a random intercept for family.

To assess whether the relation between status and FA was confounded by the group differences on gender, age, ethnicity, IQ, BMI, or tobacco use, we added them as independent variables to the regression models. Post-hoc analysis showed that cannabis use could not be controlled for as the use of tobacco and cannabis among participants was largely redundant. Parallel slope assumptions were tested with the group status by potential confounder interaction term. When the parallel slope assumption was not met, we report the results stratified by covariate level. We also added the results of the adjusted total AA/DHA ratio, the total w6/w3 ratio of the a priori FA and the total w6/w3 ratio of all analyzed FA, providing a possible indication of the patients’ inflammatory status.

For the a priori selected FA, we used a total of 6 tests. Given the fact that the field is still in a hypothesis generating phase concerning the presence of variations of specific FA in schizophrenia and their mutual relationship, we consider all tests as exploratory and decided not to correct for multiple testing at all and used a significance threshold of .05 for all tests. Because there is still some discussion among statisticians on this topic, we present the exact P values for all FA so that a reader can adjust the significance threshold if he or she wishes. All analyses were performed with SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

Sample Characteristics

FA data were available for 500 subjects (215 patients, 187 siblings, and 98 controls). Baseline and sociodemographic characteristics of the 3 groups are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Description of Study Sample: Patients, Siblings, and Controls

| Variable | Patients (N = 215) | Siblings (N = 187) | Controls (N = 98) | χ2 or F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: Male, % | 84.2 | 42.8 | 62.2 | 75.0 | <.001 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 26.3 (7.6) | 27.6 (8.5) | 27.6 (10.4) | 1.4 | .256 |

| Ethnicitya (%) | |||||

| European | 63.7 | 74.3 | 77.6 | 14.0 | .30 |

| North-African | 4.2 | 3.2 | 5.1 | ||

| Surinamese | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.1 | ||

| Turkish | 3.3 | 3.7 | 0 | ||

| Dutch Caribbean | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mixed | 14.4 | 11.2 | 6.1 | ||

| Other | 2.8 | 1.6 | 3.1 | ||

| IQb mean (SD) | 94.1 (16.2) | 102.9 (14.6) | 105.8 (16.3) | 23.9 | <.001 |

| BMIc mean (SD) | 24.2 (4.6) | 23.0 (3.4) | 22.5 (2.8) | 8.2 | <.001 |

| Cannabisd | |||||

| Urine positive % | 17.7 | 7.0 | 8.2 | 11.7 | .003 |

| Tobaccoe | |||||

| Daily/12 mo.% | 66.0 | 33.7 | 26.5 | 63.4 | <.001 |

aMissings patients, siblings, controls (%): 6.5; 2.1; 5.0

bIQ = Intelligence Quotient

Missings patients, siblings, controls (%): 7.0; 9.0; 4.0

cBMI = Body Mass Index

Missings patients, siblings, controls (%): 9.3; 10.0; 4.1

dMissings patients, siblings, controls (%): 7.4; 9.6; 13.3

eMissings patients, siblings, controls (%): 3.7; 3.2; 4.1

The 3 groups differed significantly with respect to gender (P < .001). Both siblings and controls had a significantly higher IQ compared to patients (both: P < .001). Patients had significant higher BMI compared to siblings (P = .009) and to controls (P = .001). The daily use of tobacco for the last 12 months differed between patients (66.0%), siblings (33.7%), and controls (26.5%) (P < .001).

Of the 215 patients included in this analysis, 194 (90.2%) were diagnosed with a nonaffective psychotic disorder (schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder), and 21 (9.8%) with a psychosis NOS. For clinical characteristics of the patients see table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristic of Patients (Outpatient %) N = 215 (87)

| Diagnosis (%) | |

| Schizophrenia, paranoid | 52.6 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 16.7 |

| Psychosis NOS | 9.8 |

| Schizophrenia, disorganized | 5.6 |

| Schizophrenia, not differentiated | 5.6 |

| Schizophrenia, other/residual | 5.1 |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 4.7 |

| Age of onseta (y) mean (SD) | 21.5 (6.3) |

| DUIb (y) mean (SD) | 4.1 (4.1) |

| Number of psychotic episodesc (%) | |

| 1 | 63.3 |

| 2 | 23.7 |

| 3 | 8.8 |

| >3 | 2.8 |

| Antipsychotic use overalld (%) | |

| No AP | 2.3 |

| Typical AP | 22.3 |

| Atypical AP | 61.9 |

| PANNS positive symptom scoree mean (SD) | 12.3 (5.1) |

| PANNS negative symptom scoref mean (SD) | 16.1 (6.3) |

| PANNS psychopathology scoreg mean (SD) | 28.0 (8.2) |

Note: AP, Antipsychotic; DUI, Duration of illness; NOS, Not Otherwise Specified, PANNS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

aMissings (%): 2.3.

bMissings (%): 10.0.

cMissings (%): 1.4.

dMissings (%): 13.5.

ePositive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Missings (%): 5.5.

fPositive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Missings (%): 6.0.

gPositive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Missings (%): 5.5.

Concentrations of FA Between Patients, Siblings, and Controls

Table 3 shows the comparison of the 6 a priori selected FA as well as the exploratory FA between patients, siblings, and controls.

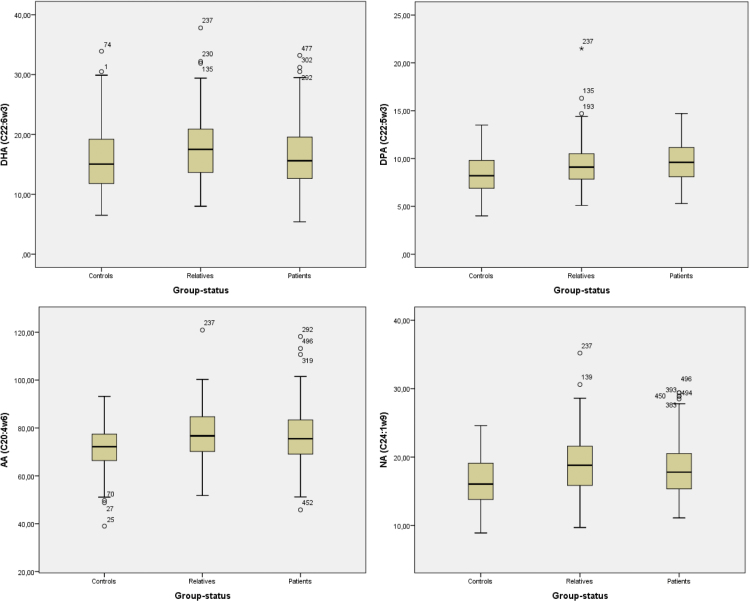

Table 4 specifies the results of the multilevel analyses for the 6 a priori selected FA. Compared to controls, both patients and siblings showed significantly increased DHA (P = .046; P = .042), DPA (P = .001; P = .001), AA (P = .019; P < .001), and NA (P = .001; P < .001) (P values reflect the comparisons of patients vs controls and siblings vs controls, respectively), See also figure 1.

Table 4.

A Priori Selected FA, Adjusted for Gender, IQ, BMI, Tobacco Use

| Adjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE b | 95% CI | P | |

| DHA (C22:6w3) | ||||

| Intercept | 12.30 | 2.50 | 7.38 17.22 | <.001 |

| Status (overall) | .087 | |||

| Controls/patients | −1.45 | 0.72 | −2.87 −0.025 | .046 |

| Siblings/patients | −0.026 | 0.58 | −1.17 1.12 | .965 |

| Siblings/controlsa | 1.42 | 0.70 | 0.05 2.79 | .042 |

| DPA (C22:5w3) | ||||

| Intercept | 8.40 | 1.00 | 6.44 10.36 | <.001 |

| Status (overall) | .002 | |||

| Controls/patients | −0.95 | 0.29 | −1.51 −0.38 | .001 |

| Siblings/patients | −0.02 | 0.23 | −0.47 0.43 | .930 |

| Siblings/controlsa | 0.93 | 0.28 | 0.38 1.47 | .001 |

|

AA (C20:4w6) Intercept |

76.79 | 5.100 | 66.77 86.80 | <.001 |

| Status (overall) | <.001 | |||

| Controls/patients | −3.46 | 1.48 | −6.37 −0.56 | .019 |

| Siblings/patients | 2.18 | 1.17 | −0.13 4.48 | .064 |

| Siblings/controlsa | 5.64 | 1.42 | 2.85 8.44 | <.001 |

| LA (C18:2w6) | ||||

| Intercept | 74.39 | 5.71 | 63.16 85.62 | <.001 |

| Status (overall) | .098 | |||

| Controls/patients | −2.62 | 1.64 | −5.85 0.61 | .112 |

| Siblings/patients | 0.76 | 1.37 | −1.93 3.45 | .579 |

| Siblings/controlsa | 3.38 | 1.58 | 0.28 6.48 | .033 |

| NA (C24:1w9) | ||||

| Intercept | 15.49 | 1.80 | 11.95 19.03 | <.001 |

| Status (overall) | <.001 | |||

| Controls/patients | −1.78 | 0.53 | −2.83 −a0.74 | .001 |

| Siblings/patients | 0.63 | 0.39 | −0.14 1.41 | .108 |

| Siblings/controlsa | 2.42 | 0.51 | 1.41 3.43 | <.001 |

| EPA (C20:5w3)b | ||||

| Intercept | 0.39 | 0.95 | −0.92 2.69 | .682 |

| Status (overall) | .243 | |||

| Controls/patients | −0.31 | 0.18 | −0.73 −0.32 | .058 |

| Siblings/patients | −0.04 | 0.19 | −0.52 0.23 | .888 |

| Siblings/controlsa | 0.28 | 0.18 | −0.92 0.59 | .079 |

aBecause the regression coefficients of the dummy variables based on the dummy variable coding of the regression analyses only resulted in estimates for the differences between controls and patients and siblings and patients, we re-analyzed the data with an alternative dummy variable coding that also enabled us to estimate the adjusted differences between siblings and controls: coding: controls/ patients: 1/0; coding: siblings/patients: 1/0; coding: siblings/controls: 1/0.

bBootstrap results based on 2000 bootstrap samples.

Fig. 1.

Boxplots of the 4 significant different RBC FA (DHA, DPA, AA, and NA).

BMI did not fulfill the parallel slope criterion for DHA and NA. The results showed that DHA and NA were significantly higher in both patients and siblings as compared to controls for BMI = 20. For higher BMI values, there was no significant group status difference. The results for the stratified data are provided as supplementary data S1.

LA was significantly higher in siblings (but not patients) compared to controls (P = .033). No significant group status differences were found for EPA (P = .058; P = .079).

Results of the post-hoc analysis investigating FA levels as fractions of the amount of total FA showed that the fraction DPA/total FA is significantly higher in patients compared to controls, with an intermediate level for siblings. Complete results are given in supplementary data S2. Results of the post-hoc analysis investigating the adjusted ratios of total AA/DHA, total w6/w3 for the a priori FA, and total w6/w3 for all FA showed no significant differences between the 3 groups (see table 3).

For the FA which were analyzed on an exploratory basis, we found significant differences between groups for: C16:0, C18:0, C20:0, C22:0, C24:0, C18:3w3, C20:3w6, C22:4w6, C22:5w6, C18:1w7, C18:1w9, and Total FA. Inspection of the means of the 3 groups showed a consistent pattern of higher concentrations in patients and siblings as compared to controls (see table 3).

Association of FA Concentrations and Clinical Parameters

We investigated a possible association of FA concentrations and duration of illness, episodes of psychosis, use of typical and atypical antipsychotics or antipsychotic naive, ethnicity, and current mood disorder. They were not significant (see supplementary data S3). We also investigated the PANNS positive and PANNS negative scores and found significant negative correlations for DHA (r = −.20; P = .005; r 2 = .04), NA (r = −.16; P = .020; r 2 = .03), and EPA (r = −.18; P = .010; r 2 = .03). Although the effect size is weak, these findings are in line with other studies, stating lower FA with increasing negative symptoms (see supplementary data S3).21–23

Discussion

We found a consistent pattern of higher RBC FA in patients and siblings compared to controls. Of the a priori selected FA DHA, DPA, AA, and NA were significantly higher in both patients and siblings compared to controls. LA was significantly higher in siblings, but not in patients, compared to controls. Of the 21 FA, and the total FA concentration, analyzed on an exploratory basis, 12 were significantly higher in patients and/or siblings as compared to controls.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study to date investigating FA in patients with schizophrenia and psychosis spectrum disorders and the first study to investigate FA in a large sample of first-degree relatives of these patients.

Our findings are in contrast with several previous studies, which in general show decreased FA in patients compared to controls.10,12,14–17,21,24–29 However, as pointed out in 2 recent meta-analyses, previous studies should be interpreted cautiously due to large clinical and methodological heterogeneity and moderate study quality.8,9 Furthermore, some studies did find elevated FA in patients, like we did. Peet11 compared drug-naive or long-term unmedicated patients with healthy controls and found significant higher DHA in patients compared to controls. Arvindakshan et al12 found higher AA in patients before supplementation of omega-3 FA and antioxidants. McNamara et al13 reported—non-significant—higher AA, DHA, and total PUFA in patients compared to controls. Evans et al14 compared first-episode psychotic patients at baseline and after a 6-months treatment period with antipsychotics. In patients, they found higher LA and normal AA at baseline, and significantly higher AA and normal other PUFA after the antipsychotic treatment. Obi and Nwanze15 found significantly higher proportions of linolenic acid (18:3w3) in plasma and RBC membranes. Finally, Vaddadi et al16 found that all patients had significant elevated DPA and nonsignificant higher dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid (C20:3w6) and DHA compared to controls. Therefore, although the majority of studies report lower RBC FA in patients, as shown in the meta-analyses by Hoen et al9 and Van der Kemp et al,8 the findings of our study are consistent with a considerable number of studies that report higher FA in patients.

Importantly, all previous studies, except a preliminary study by Peet et al17 compared patients to controls. Our findings are underscored by the fact that we included healthy siblings of patients with schizophrenia and observed similar directions of change in FA of these siblings, as present in the patients. It should be emphasized that our findings are conditional on a number of factors. Some of these factors we have controlled for, however, we could not control for the effect of stage of disorder “acute vs remitted” due to the very few number of acutely ill patients present in this study. The same holds for drug-naive patients, as these were only present in 2.3% of the sample.

There are a number of possible explanations for the heterogeneity in study results comparing our study and others: heterogeneity between patients, importantly phase of the disorder (acutely ill, remitted, or partly remitted), duration of illness, effects of prolonged use of medication, and environmental influences (ie, urbanization, early life stress, or dietary factors).

It is widely acknowledged that schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder. The clinical manifestation of schizophrenia is probably influenced by several interacting neurodevelopmental processes (ie, apoptosis, myelination, subtle prenatal deficits in neural assemblage), as well as by environmental influences.1,2,30–32 Recent studies for example identified aberrant immune activation in some patients—but not all—as a predisposing factor for schizophrenia.33–38 Patients may differ with respect to dominant processes associated with the illness, even within, eg, a recent-onset group. Possibly, specific patient groups may be predominant in one society or research setting as compared to another. The vast majority of our patients was not acutely ill and in a remitted or partly remitted phase of disorder, and outpatient. This implicates that our findings hold for this specific group and possibly explains the differences in findings compared to studies like Bentsen et al39 who studied acutely ill patients.

A potential explanation for the differences in FA concentrations between patients and healthy controls could be differences in prevalence of current mood disorders. We checked this in our study and found that after adjustment for current mood disorder, the differences remained (data available on request).

Also the developmental character of the disorder may affect RBC FA. Normal brain development is, among others, characterized by prolonged myelination, well into the fourth decade, and a gradual decline thereafter.30,40 In schizophrenia, this process may be altered. Therefore, one cannot readily compare older patients with younger ones or untreated with treated. Those previous studies that are most similar to our study (relatively young patients, urban environment, industrialized, western society) are the ones by Assies et al,10 Bentsen et al,39 Khan et al,41 Reddy et al,28 Yao et al,42 and Evans et al14 Of these 6 studies, Assies et al and Evans et al report higher RBC AA, and lower other FA, the other studies report lower RBC FA.

Apart from phase of illness, pharmacological treatments may affect FA. The use of antipsychotics has complex effects, which may have impact on brain development, glucose and lipid metabolism, neurotransmitter metabolism, or directly affect RBC FA composition.11,12,14,21,28,30,41,43–48

Antipsychotic use, therefore, introduces another source of heterogeneity. Previous studies suggest different effects of typical or atypical antipsychotic use and of first episode- and chronic psychotic patients. Use of atypical antipsychotics is also potentially associated with antioxidant effects and reduced lipid peroxidation, where typical antipsychotics are supposed to be pro-oxidant.44,49

However, by investigating unaffected and untreated siblings of schizophrenia patients, whom show similar RBC FA variations as the patients, we argue that the observed higher RBC FA probably are not caused by the use of antipsychotic medication and are not a result of the early clinical symptomatic manifestation of the disorder, as the siblings are asymptomatic. We cannot completely rule out that siblings that show elevated RBC FA may develop schizophrenia later on, and thus that higher RBC FA do not merely represent genetic risk, but are indicative of a prodromal, asymptomatic phase of the disorder at the time of sampling. This is however unlikely, as the number of siblings that will make a transition to psychosis will be small.

We argue that the higher RBC FA either represent the influence of shared environmental factors or are a manifestation of genetic liability. Although well-known environmental factors that influence the expression of schizophrenia liability are cannabis use, growing up in an urban environment, and childhood-trauma, most researchers focus on dietary factors. Especially, the PUFA alpha-Linolenic acid (C18:3w3), LA, DHA, and AA are extensively researched, in particular whether a poor diet is related to variations in FA in schizophrenia patients and, if so, whether treatment with these FA improves symptoms.50–55 A review by Peet,11 describes that a “Western” diet—rich of high saturated fat, high sugar, and low polyunsaturated fat—is associated with a worse outcome of disease. In this review, the studies on supplementing EPA or DHA to the diet of patients showed partly positive benefits, but a systematic review concluded that the use of omega-3 PUFA still remains experimental and inconclusive.56 Bentsen et al39 mentioned that the link between diet and RBC PUFA is weaker in schizophrenia patients than in normal subjects and a deficient diet did not explain low levels of RBC PUFA.

Interestingly, our study found an indication for modification of RBC FA by BMI, which is likely related to diet. Our results show higher RBC FA in patients with lower BMI. Using nonfasting blood samples—as in this study—is not likely to have impact on acute RBC FA status. The lifespan of approximately 120 days makes the erythrocyte more stable over time and, in contrast to plasma, insensitive to fasting status.57,58

An interesting explanation with respect to patient heterogeneity is the possibility of a bimodal distribution of FA, mentioned by several authors.17,22,27,39 This suggests that there are 2 peaks in FA distributions within there is a possibility that patients belonging to a “low level” or a “high level” may represent subgroups of the disease, including different endophenotypes and/or clinical characteristics. One hypothesis is that RBC FA are bimodally distributed during an acute phase of the disorder. Possible FA levels may be downregulated following genetically determined redox regulatory problems present in only a subgroup of the patients, the other subgroup having FA not different from healthy controls.22,39 Another theory is that RBC FA are lower in a group of patients with mainly negative symptoms.21,22 At present, the evidence of a bimodal distribution seems to be especially compelling for acutely ill patients,39 the possibility of a bimodal distribution in acutely ill patients, stabilized patients, or other patient subgroups should be further explored in future studies.

Finally, as argued by Mocking et al,20 heterogeneity may arise from the method of presenting data as either concentrations or percentages of total FA. Differences may depend on individual FA characteristics. Mocking et al emphasize the importance of a hypothesis-driven choice of method to use, suggesting the use of absolute concentrations if researching a FA itself, independent of the concentration of other FA. We have chosen concentrations as our main outcome, and to provide percentages as additional, post-hoc data, so the comparison of both methods of presentation may provide a guideline for future research. Interesting in this regard is that the significant findings that were observed when FA were presented as concentrations were mostly lost (all except DPA) when FA were expressed as percentages. This implies that the absolute concentrations of FA are important in schizophrenia’s pathophysiology, as opposed to their relative amount. Because of the many roles of FA in brain pathophysiology, it still seems premature to express one overall theory to explain all observed FA variations. While DPA is usually regarded as an intermediate in the conversion of the more bioactive EPA into DHA, our results suggest that it is the omega-3 PUFA that is most outspokenly different in schizophrenia patients, which merits further investigation. Because AA is an important precursor of proinflammatory eicosanoids, the observed higher AA may resemble activation of inflammatory pathways that has been implicated in schizophrenia pathophysiology.6,33,38,59–62 Finally, NA is a main constituent of myelin; the observed significant differences may partly explain white matter alterations observed in schizophrenia, which is also supported by imaging research.6,63 Overall, FA variations most likely resemble a complex balance between inflammatory, oxidative stress, and myelination pathways.

One obvious explanation for our findings is that higher levels of FA originate from shared environmental factors between patients and their siblings, most likely dietary factors. Other environmental factors, ie, infections or other immune-related effects, should be considered. Another explanation is that FA levels are genetically determined.

In addition to shared environmental and genetic risk factors, we speculate on the existence of unidentified sub-syndromes of schizophrenia, characterized by higher RBC FA as compared to controls, and which are overrepresented in our study population. There are several potential confounders that might explain the differences in FA concentrations between the patient groups. However, we tested for a large number of these variables whether they were related to FA concentrations. This was not the case. Therefore, it is unlikely that group differences on these variables confounded the effect of patient status of FA concentration.

An important strength of our study is the large number of patients evaluated. A second strength is the inclusion of asymptomatic siblings. Thirdly, we investigated relatively homogeneous groups. We also consider the large array of FA measured a strength. A limitation is that our study is cross-sectional, limiting the assessment of causal relationships, other than explained by the presence of asymptomatic siblings. We have limited data on the dietary habits of patients, siblings, and controls. Furthermore, controls are not completely matched on the patients with respect to education and may be subjected to selection bias, because the responding randomly recruited controls could be more interested in health issues than others, accompanied by a healthier lifestyle.

To summarize, we find a large number of consistently higher RBC FA in both schizophrenia patients and unaffected siblings as compared to controls. We most likely attribute these higher concentrations to a shared environment or a genetic liability between patients and siblings. Our findings contrast (most) other reports, which generally show lower FA, although there is a substantial heterogeneity in the available evidence. We therefore emphasize that schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder, and that our findings may be valid for a specific patient group investigated by us: young, recent-onset patients, not in an acute phase of the disorder, from an urbanized western society.

An important issue for further research is the possible presence of a bimodal distribution of RBC FA. Further research should focus on identifying the possible presence of subgroups with either higher, normal, or lower RBC FA, the factors influencing the presence of these subgroups, and the influence of environment vs genetic factors related to RBC FA.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

The work has been in part made possible by a unrestricted personal grant to NJM van Beveren by Antes Center for Mental Health care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of the GROUP study and for their generosity of time and effort. We also thank psychiatrist W. Hoen for her time and effort. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bartzokis G. Schizophrenia: breakdown in the well-regulated lifelong process of brain development and maturation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:672–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guest J, Garg M, Bilgin A, Grant R. Relationship between central and peripheral fatty acids in humans. Lipids Health Dis. 2013;12:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Das UN. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in the pathobiology of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;42:122–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Assies J, Mocking RJ, Lok A, Ruhé HG, Pouwer F, Schene AH. Effects of oxidative stress on fatty acid- and one-carbon-metabolism in psychiatric and cardiovascular disease comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130:163–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Watson JD. Molecular Biology of the Cell: Garland Science; 3rd edition New York and London: Garland Publishing; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horrobin DF, Glen AI, Vaddadi K. The membrane hypothesis of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1994;13:195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van der Kemp WJ, Klomp DW, Kahn RS, Luijten PR, Hulshoff Pol HE. A meta-analysis of the polyunsaturated fatty acid composition of erythrocyte membranes in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;141:153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoen WP, Lijmer JG, Duran M, Wanders RJ, van B, everen NJ, de H, aan L. Red blood cell polyunsaturated fatty acids measured in red blood cells and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2013;207:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Assies J, Lieverse R, Vreken P, Wanders RJ, Dingemans PM, Linszen DH. Significantly reduced docosahexaenoic and docosapentaenoic acid concentrations in erythrocyte membranes from schizophrenic patients compared with a carefully matched control group. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:510–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peet M. Nutrition and schizophrenia: beyond omega-3 fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;70:417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arvindakshan M, Ghate M, Ranjekar PK, Evans DR, Mahadik SP. Supplementation with a combination of omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants (vitamins E and C) improves the outcome of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;62:195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McNamara RK, Rider T, Jandacek R, Tso P. Abnormal fatty acid pattern in the superior temporal gyrus distinguishes bipolar disorder from major depression and schizophrenia and resembles multiple sclerosis. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215:560–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Evans DR, Parikh VV, Khan MM, Coussons C, Buckley PF, Mahadik SP. Red blood cell membrane essential fatty acid metabolism in early psychotic patients following antipsychotic drug treatment. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003;69:393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Obi FO, Nwanze EA. Fatty acid profiles in mental disease. Part 1. Linolenate variations in schizophrenia. J Neurol Sci. 1979;43:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vaddadi KS, Gilleard CJ, Soosai E, Polonowita AK, Gibson RA, Burrows GD. Schizophrenia, tardive dyskinesia and essential fatty acids. Schizophr Res. 1996;20:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peet M, Laugharne JD, Mellor J, Ramchand CN. Essential fatty acid deficiency in erythrocyte membranes from chronic schizophrenic patients, and the clinical effects of dietary supplementation. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1996;55:71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Arndt S. The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH). An instrument for assessing diagnosis and psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Korver N, Quee PJ, Boos HB, Simons CJ, de Haan L; GROUP investigators. Genetic Risk and Outcome of Psychosis (GROUP), a multi-site longitudinal cohort study focused on gene-environment interaction: objectives, sample characteristics, recruitment and assessment methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:205–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mocking RJ, Assies J, Lok A, et al. Statistical methodological issues in handling of fatty acid data: percentage or concentration, imputation and indices. Lipids. 2012;47:541–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sethom MM, Fares S, Bouaziz N, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids deficits are associated with psychotic state and negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2010;83:131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bentsen H, Osnes K, Refsum H, Solberg D, Bohmer T. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of an omega-3 fatty acid and vitamins E+C in schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bentsen H, Solberg DK, Refsum H, Bøhmer T. Clinical and biochemical validation of two endophenotypes of schizophrenia defined by levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids in red blood cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2012;87:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peet M, Laugharne J, Rangarajan N, Horrobin D, Reynolds G. Depleted red cell membrane essential fatty acids in drug-treated schizophrenic patients. J Psychiatr Res. 1995;29:227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peet M, Shah S, Selvam K, Ramchand CN. Polyunsaturated fatty acid levels in red cell membranes of unmedicated schizophrenic patients. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2004;5:92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ranjekar PK, Hinge A, Hegde MV, et al. Decreased antioxidant enzymes and membrane essential polyunsaturated fatty acids in schizophrenic and bipolar mood disorder patients. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glen AI, Glen EM, Horrobin DF, et al. A red cell membrane abnormality in a subgroup of schizophrenic patients: evidence for two diseases. Schizophr Res. 1994;12:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reddy RD, Keshavan MS, Yao JK. Reduced red blood cell membrane essential polyunsaturated fatty acids in first episode schizophrenia at neuroleptic-naive baseline. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:901–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kemperman RF, Veurink M, van der Wal T, et al. Low essential fatty acid and B-vitamin status in a subgroup of patients with schizophrenia and its response to dietary supplementation. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;74:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haroutunian V, Katsel P, Roussos P, Davis KL, Altshuler LL, Bartzokis G. Myelination, oligodendrocytes, and serious mental illness. Glia. 2014;62:1856–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hashimoto M, Maekawa M, Katakura M, Hamazaki K, Matsuoka Y. Possibility of polyunsaturated fatty acids for the prevention and treatment of neuropsychiatric illnesses. J Pharmacol Sci. 2014;124:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Janssen CI, Kiliaan AJ. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) from genesis to senescence: the influence of LCPUFA on neural development, aging, and neurodegeneration. Prog Lipid Res. 2014;53:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schwarz E, van Beveren NJ, Ramsey J, et al. Identification of subgroups of schizophrenia patients with changes in either immune or growth factor and hormonal pathways. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peet M. The metabolic syndrome, omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes in relation to schizophrenia. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rao JS, Kim HW, Harry GJ, Rapoport SI, Reese EA. Increased neuroinflammatory and arachidonic acid cascade markers, and reduced synaptic proteins, in the postmortem frontal cortex from schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2013;147:24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sommer IE, van Westrhenen R, Begemann MJ, de Witte LD, Leucht S, Kahn RS. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory agents to improve symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: an update. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:181–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hibbeln JR, Makino KK, Martin CE, Dickerson F, Boronow J, Fenton WS. Smoking, gender, and dietary influences on erythrocyte essential fatty acid composition among patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:431–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Drexhage RC, Weigelt K, van Beveren N, et al. Immune and neuroimmune alterations in mood disorders and schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;101:169–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bentsen H, Solberg DK, Refsum H, et al. Bimodal distribution of polyunsaturated fatty acids in schizophrenia suggests two endophenotypes of the disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bartzokis G. Neuroglialpharmacology: myelination as a shared mechanism of action of psychotropic treatments. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:2137–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khan MM, Evans DR, Gunna V, Scheffer RE, Parikh VV, Mahadik SP. Reduced erythrocyte membrane essential fatty acids and increased lipid peroxides in schizophrenia at the never-medicated first-episode of psychosis and after years of treatment with antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2002;58:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yao Jk, Stanley JA, Reddy RD, Keshavan MS, Pettegrew JW. Correlations between peripheral polyunsaturated fatty acid content and in vivo membrane phospholipid metabolites. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yao JK, van Kammen DP, Welker JA. Red blood cell membrane dynamics in schizophrenia. II. Fatty acid composition. Schizophr Res. 1994;13:217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang XY, Tan YL, Cao LY, et al. Antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in different forms of schizophrenia treated with typical and atypical antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2006;81:291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Stewart SB, et al. In vivo evidence of differential impact of typical and atypical antipsychotics on intracortical myelin in adults with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;113:322–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Amar CP, et al. Long acting injection versus oral risperidone in first-episode schizophrenia: Differential impact on white matter myelination trajectory. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gilca M, Piriu G, Gaman L, Delia C, Iosif L, Atanasiu V, Stoian I. A study of antioxidant activity in patients with schizophrenia taking atypical antipsychotics. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:4703–4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thompson PM, Bartzokis G, Hayashi KM, et al. ; HGDH Study Group. Time-lapse mapping of cortical changes in schizophrenia with different treatments. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:1107–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mahadik SP, Evans D, Lal H. Oxidative stress and role of antioxidant and omega-3 essential fatty acid supplementation in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001;25:463–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Amminger GP, Schäfer MR, Papageorgiou K, et al. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:146–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids plus an antioxidant for relapse prevention after antipsychotic discontinuation in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;158:230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fenton WS, Hibbeln J, Knable M. Essential fatty acids, lipid membrane abnormalities, and the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:8–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mossaheb N, Schäfer MR, Schlögelhofer M, et al. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of young patients at risk for psychosis: when do they begin to be effective? Schizophr Res. 2013;148:163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, Morrison AP, Kendall T. Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Strassnig M, Singh Brar J, Ganguli R. Dietary fatty acid and antioxidant intake in community-dwelling patients suffering from schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;76:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Irving CB, Mumby-Croft R, Joy LA. Polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; 3:1–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hodson L, Skeaff CM, Fielding BA. Fatty acid composition of adipose tissue and blood in humans and its use as a biomarker of dietary intake. Prog Lipid Res. 2008;47:348–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Harris WS, Varvel SA, Pottala JV, Warnick GR, McConnell JP. Comparative effects of an acute dose of fish oil on omega-3 fatty acid levels in red blood cells versus plasma: implications for clinical utility. J Clin Lipidol. 2013;7:433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Skosnik PD, Yao JK. From membrane phospholipid defects to altered neurotransmission: is arachidonic acid a nexus in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia? Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003;69:367–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Drexhage RC, van der Heul-Nieuwenhuijsen L, Padmos RC, et al. Inflammatory gene expression in monocytes of patients with schizophrenia: overlap and difference with bipolar disorder. A study in naturalistically treated patients. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:1369–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. van Beveren NJ, Schwarz E, Noll R, et al. Evidence for disturbed insulin and growth hormone signaling as potential risk factors in the development of schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schwarz E, Guest PC, Rahmoune H, et al. Identification of a biological signature for schizophrenia in serum. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Peters BD, Machielsen MW, Hoen WP, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acid concentration predicts myelin integrity in early-phase psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:830–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.