Abstract

The idea that psychiatric diagnoses are not mere descriptors of a symptomatology but create incrementally negative effects in patients has received considerable support in the literature. The flipside to this effect, that calling someone by a psychiatric diagnosis also has an effect on how this person is perceived by others, however, has been less well documented and remains disputed. An experimental study was conducted with a large sample (N = 2265) to ensure statistical power to detect even small effects of such adding a psychiatric diagnosis to a description of symptoms or not. Dependent variables were chosen in an exploratory manner and tests were corrected for alpha inflation. Results show that calling the identical symptomatology schizophrenia (vs not labeling it) led to greater perceptions of aggressiveness, less trustworthiness, more anxiety toward this person, and stronger assumptions this person feels aggression-related emotions. Although stigmatizing attitudes were generally lower for persons with personal experiences with mental illnesses as either a patient or a close relative, such personal involvement did not moderate the effect. Implications of these findings and limitations of the study are discussed.

Key words: stigma, social distance, stereotypes, infrahumanization, labeling, social perception

Introduction

About 1% of the world population is estimated to suffer from schizophrenia. Symptoms associated with diagnoses include disorganized speech and behavior as well as a lack of motivation to do anything or care about things. Clearly, such symptoms bear the potential of severely impairing one’s own life quality. Above and beyond these direct costs on well-being, there may also be indirect, socially mediated costs. Specifically, people might perceive carriers of these symptoms as weird, confused, unpredictable, and maybe even dangerous. The present research sought to test the long-standing hypothesis that these negative perceptions are intensified if introduced as symptoms of schizophrenia.

Stigma of Schizophrenia

The stigma of mental illness in general and schizophrenia in particular has been a long-debated issue, due to its negative effect on patients’ social life, life quality, and recovery. On a global scale, roughly half of patients with schizophrenia experienced negative discrimination.1 People with schizophrenia are generally viewed negatively by the public,2 a perception that has intensified over recent years.3 Common attributes ascribed to schizophrenic patients are that they are dangerous, aggressive, and unpredictable,4–11 a stereotype that is often reinforced by media images of extremely violent mentally ill characters.12

Labeling and Stigma

From very early theorizing on the act of labeling was understood as one of the key prerequisites for the stigmatization of a certain condition: In its extreme form, this theory asserts that only by inventing a social identity label meaning can be attached to this label. Thus, it is only the process of labeling (randomly fluctuating) deviant behavior as a certain condition that turns this into a permanent condition by creating certain expectancies in the environment which then reinforce stereotypic behavior and thereby creates the symptomatology.13,14 This provocative view came under some attack for attributing the very emergence of mental illness to societal reactions15–17 which has led to a modified labeling approach 18 which concedes that there may be negative effects solely attributable to an actual psychopathology but that labeling also creates additional negative outcomes. In that view, labeling does not cause a mental disorder but incrementally adds to its negative effects. Following this line of thinking, the present article explores whether mentioning a schizophrenia diagnosis will lead to more negative perceptions of this person. Although the term label has regularly been associated with the older notion of an arbitrarily invented social identity, we explicitly do not dispute the psychological reality of a mental illness, but merely use the term to denote to the diagnostic process of giving a name (ie, a label) to a symptomatology.

Support for the detrimental effects of being diagnosed as mentally ill comes from a variety of studies. “Schizophrenics” (vs “consumers of mental health services”) were perceived to be more dangerous, less likely to recover and evoked greater desire for social distance19 in the absence of any concrete description of a patient. In all likelihood, these 2 labels made respondents imagine 2 completely different persons, and it remains unclear whether these reactions would also transfer to labeled person on which recipients had any other information to make a judgment. Other studies have paired the label (no label) with different behavioral description,20 again leaving it ambiguous whether the reported discomfort in the presence of that person is indeed attributable to the (abstract) label or rather to the (concrete) symptomatic behavior.

Tackling the question of such negative labeling effects requires the comparison of 2 persons (or groups) that differ in nothing but whether their condition is diagnosed as mentally ill or not. Specifically, they should not differ in terms of behavior, symptoms, or any other relevant factor. Thus, to test whether receiving a diagnosis has a negative effect on patient well-being, the adequate control group would not be healthy community members21 but untreated individuals who are similarly “impaired” in terms of their symptomatology.18,22–24 The latter studies’ finding that—all other conditions equal—having received a formal diagnosis increased the diagnosed persons’ anticipated stigma and reduced quality of life served as convincing support for the modified labeling approach’s assumption about negative effects of receiving a diagnosis.

Mirroring evidence on the side of social perception is still scarce. Although at the core of labeling theory, very few studies have pinpointed whether the presence (vs absence) of a diagnostic label changes the way individuals perceive and judge other persons. Some studies presented clinical cases without a diagnosis and tested whether respondents’ spontaneous tendency to label these cases as mental disorders correlated positively with ascriptions of dangerousness and desire for greater social distance.25 As this approach relied on a correlation (of negative attitudes with the inclination to spontaneously award a diagnostic label), it remains ambiguous with regard to causality (for a null or even a reverse correlative effect see Wright et al11 and Yap et al26). It is conceivable that the act of labeling evoked negative attitudes, but it is also conceivable that negative reactions increased the desire to label and classify the case, or that a third variable (eg, negative visceral reactions) caused both.

One of the few experimental studies16 manipulated the description of typical behavior exhibited by the patient, whether the patient’s condition was called “mentally ill,” “wicked,” or “under stress” and whether this label was offered as interpretation by either the patient, his family, “some people,” or a psychiatrist. Additionally, three conditions introduced the behavior without any interpretation (thus neither a label nor a labeler). Neither the label nor the source of labeling had any effect on social rejection. As the only effect, strongly deviant behavior led to greater social rejection, leading to the conclusion that “the role of labeling in determining people’s reactions to the mentally ill needs to be greatly de-emphasized” (p. 115; for more recent examples of null effects see Boisvert et al,27 Kirmayer et al,28 and Schwartz et al29). Thus, so far there is mixed evidence at best for the causal effect of a diagnosis (while behavioral description are held constant) on stigmatizing attitudes. This may either be attributable to the fact that such an effect of a label on a social perceiver does not exist or that the magnitude of this effect is too subtle to detect it with the modest sample sizes typically employed in experimental studies.

The Present Research

To experimentally test with a large sample whether the schizophrenia diagnosis would have any effect on stigmatizing attitudes above and beyond behavioral descriptions, 2 vignettes were created that were exactly identical in how they described a patient’s symptoms but differed as to whether the attending psychiatrist (correctly) identified this symptomatology as indicative of schizophrenia or not. Afterward social perception, stigmatizing attitudes as well as a subtle measure of infrahumanization were assessed.

Methods

Sample

To have statistical power to detect even small effects, a large online sample was recruited by posting the link to the study on various group sites (eg, soccer fans, psychology students) on online social networks and asking participants to share it among their contacts (94% of participants were recruited over Facebook). The final sample consisted of N = 2265 complete datasets (1625 female, 621 male, 19 other/missing) in the age range from 18 to 98 (M = 24.4, SD = 8.5; 87 missing or implausible responses). The majority of participants were university students (n = 1640, 72.4%) from various majors (the largest in descending order being law studies, medicine, sociology, educational sciences, psychology; each n > 100). Students were followed by white-collar workers as the second largest group of participants (n = 299, 13.2%). The schizophrenia condition and the no-diagnosis condition did not differ in terms of age, F < 1, gender distribution, χ2 < 1, formal education, χ2(5) = 8.16, P = .15, or current occupation, χ2(8) = 7.89, P = .44. These variables thus received no further attention.

labeling Manipulation

All participants read a story about a patient with the instruction to read the text advertently as they would be quizzed about the story later. Both conditions were identical in describing how Hans H. felt uneasy, visited a psychiatrist, and described his symptoms. As the central manipulation, in the schizophrenia condition before the symptoms were mentioned, the psychiatrist is reported to diagnose schizophrenia whereas in the no-diagnosis condition, no such diagnosis is mentioned. Importantly, the following symptoms were exactly identical across conditions, making any differences between the conditions solely attributable to the mentioning of the diagnosis at the beginning of the vignette. The described symptoms were chosen in a way to represent a list of symptoms that is necessary and exhaustive to give a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to DSM-5. Specifically, it described how, over the last 6 months (duration; criterion C), Hans has been impaired in his job performance (criterion B: occupational dysfunction) and since 2 months (criterion C) has been suffering from disorganized speech (criterion A3) and his grossly disorganized behavior (criterion A4). Furthermore, he was said to feel a lack of motivation to do anything or care about things (flattened affect, avolition; criterion A5). Hallucinations or delusions were not included in the vignette as these (in a lay perspective) prototypical symptoms might evoke association of schizophrenia also in the no-diagnosis condition. After describing the symptoms, the vignette included a summary of the cover letter from the attending physician, sufficient to allow differential diagnoses: no organic cause could be found, the blood picture showed no indication of substance abuse and neither did Hans H. report to have ever abused alcohol or other substances (criterion E). Furthermore, previous depressive, manic, or mixed episodes were excluded (criterion D).

Measures

Social Perception of Target.

Participants rated Hans H. on 15 adjectives (see table 1) that represented a variety of attributes on which social stigma can be expected. Directly referring to the central stereotype of dangerousness, 2 items tapped into their perception of Hans H. as dangerous, resp. aggressive. Another 9 items reflected the 2 fundamental dimensions of social perception30: warmth (6 items) and competence (3 items). Of the remaining 4 items, 2 were associated with mental illness stigmata of reduced hygiene (dirty) but enhanced creativity (creative 31), whereas the others served as distractors (vain, enthusiastic). Although it was expected to find effects particularly on those items that fit the stereotype of schizophrenia (dangerousness), the more general items were included as an opportunity to explore the effect in-depths.

Table 1.

Self-reported Social Perception of Patient “Hans” as a Function of Schizophrenia Label

| Schizophrenia (n = 1102) | No-Diagnosis (n = 1148) | Group Differences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | d | |

| Aggressiveness | ||||||

| Aggressive | 2.16 | 0.93 | 2.03 | 0.92 | 3.43* | 0.14 |

| Dangerous | 2.25 | 1.03 | 1.99 | 0.99 | 5.98* | 0.25 |

| Warmth | ||||||

| Faithful | 3.33 | 0.76 | 3.46 | 0.80 | −3.93* | −0.17 |

| Sincere | 3.82 | 0.85 | 3.86 | 0.89 | <1 | −0.04 |

| Warm-hearted | 3.11 | 0.71 | 3.14 | 0.77 | −1.09 | −0.05 |

| Truthfully | 2.98 | 0.89 | 3.11 | 0.89 | −3.39* | −0.14 |

| Likeable | 3.18 | 0.80 | 3.21 | 0.85 | <1 | −0.04 |

| Unjust | 2.25 | 0.89 | 2.18 | 0.89 | 1.72 | 0.07 |

| Competence | ||||||

| Competent | 2.94 | 0.89 | 3.05 | 0.90 | −3.05* | −0.13 |

| Competitive | 2.16 | 0.88 | 2.12 | 0.92 | 1.04 | 0.04 |

| Independent | 2.91 | 0.99 | 2.90 | 1.00 | <1 | 0.00 |

| Miscellaneous | ||||||

| Dirty | 2.22 | 0.97 | 2.15 | 0.97 | 1.51 | 0.06 |

| Creative | 2.72 | 0.79 | 2.59 | 0.83 | 3.79* | 0.16 |

| Enthusiastic | 2.20 | 1.02 | 2.17 | 1.04 | <1 | 0.03 |

| Vain | 2.28 | 0.90 | 2.25 | 0.96 | <1 | 0.03 |

Note: All items worded “This person is …” and completed on a scale from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (fully agree).

*P < .003 (Bonferroni-corrected for 15 comparisons).

Infrahumanization.

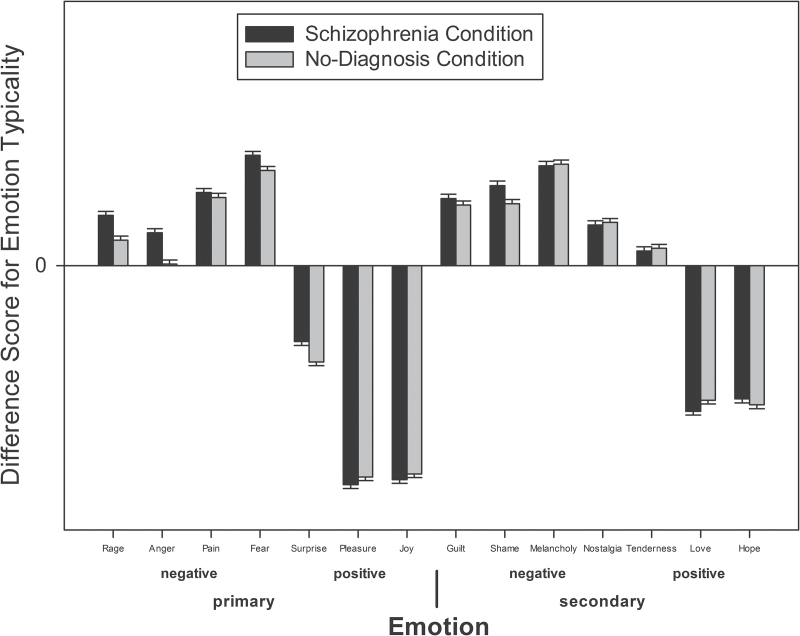

Recent research has indicated that patients with a mental (vs physical) illness are perceived as less humane.32 The current study relied on the well-established differential ascription of primary vs secondary emotions as an indicator of ascribed humanity33,34 (but see Bilewicz et al35). Specifically, participants were asked to indicate for 14 (7 primary and 7 secondary; figure 1) emotions36 how typical these were for the affective experiences of Hans H. on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very typical). To estimate the perception of Hans H. as relatively less human, the same ratings were also assessed regarding respondents’ own affective experiences. Infrahumanization would be reflected in similar ratings of the self and Hans H. on primary emotions but lesser ascriptions of secondary emotions, particularly in the schizophrenia condition.

Fig. 1.

Difference scores (patient – self) for 14 emotions as a function of schizophrenia label. Positive scores indicate that patient is more likely to feel these emotions compared to the self, negative scores indicate a decreased likelihood to experience this emotion.

Mental Illness Stigma Scale.

The Mental Illness Stigma Scale37 was adapted to “people like Hans H.”. Participants indicated their agreement on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree) with 28 items that loaded on 7 subscales. These subscales tapped into feelings of anxiety in the presence of such people, the conviction that it is difficult or impossible to maintain a personal relationship with such people (relationship disruption), the stereotype of neglected personal care (hygiene), and the conviction that the identification of Hans H.’s symptoms would be easy (visibility). The last 3 subscales concerned the constancy of the disorder, specifically the belief in the general treatability of Hans H.’s condition, as well as healthcare professionals’ (psychiatrists and psychologists) power to effectively improve the condition (professional efficacy) and the chances of complete recovery.

Personal Involvement.

As there is ample evidence in the literature that people in personal contact with mentally ill patients show less pronounced stigmatization,9,38–40 participants indicated whether they had ever suffered from a mental illness and if yes, what kind of illness. In addition, it was also inquired whether someone in their immediate social environment had suffered from a mental illness and if so, which one.

Manipulation Check.

At the end of the study, participants indicated whether any diagnosis was mentioned and if they could not remember, guessed what kind of mental illness Hans H. suffered from.

Results

All analyses were conducted for all participants as well as the remaining subsample after excluding all participants who failed the manipulation check. A failure in manipulation check was assumed for those participants in the no-diagnosis condition who guessed that Hans was suffering from schizophrenia and thereby might have self-generated the diagnosis intended to be withheld from them (n = 63) as well as those in the schizophrenia condition who incorrectly identified another disorder than schizophrenia and thus either did not remember or never noticed the diagnosis (n = 470). All results reported below became stronger after excluding these participants, but for reasons of conservative testing, all analyses are reported on the full sample.

Social perceptions of Hans H. as a function of the schizophrenia condition were subjected to 15 independent T tests, Bonferroni-adjusted for multiple comparisons (P = .003). Introducing the schizophrenia diagnosis had an amplifying effect on stereotypes of aggressiveness and dangerousness (see table 1). For the flipside of this trait, interpersonal warmth, it had the opposite effect on a composite measure (Cronbach’s α = .74) with decreased impressions of warmth for the schizophrenia, M = 3.25, SD = 0.57, compared to the no-diagnosis condition, M = 3.33, SD = 0.60, t(2689) = −3.38, P = .001, Cohen’s d = −0.13. This effect was further dissected on a single-item level, showing that the diagnosis decreased trust in Hans H. (faithful, truthful) but had no effect on good-naturedness (sincere, warm-hearted, likeable, unjust). Furthermore, in presence of the schizophrenia diagnosis, the person with the identical symptoms was seen as less competent, but more creative (table 1). Unexpectedly, the diagnosis had no effect on the perceptions of dirtiness. As an important qualification of the observed effects, it should be noted all effects were of a relatively small size, requiring at least 200 participants per condition to achieve 80% power.

An inspection of the emotion ratings suggested that participants did not infrahumanize Hans H. at all. Although the predicted interaction of target (Hans vs self) and type of emotion (primary vs secondary) was significant, F(1, 2249) = 874.10, P < .001, this was not due to lesser ascription of secondary emotions to Hans. In fact, participants attributed descriptively more secondary emotions to Hans, M = 3.24, SD = 0.50, than to themselves, M = 3.21, SD = 0.52, t(2249) = 2.29, P = .022, but ascribed less primary emotions to Hans, M = 2.81, SD = 0.49, compared to themselves, M = 3.20, SD = 0.48, t(2249) = −28.95, P < .001. Furthermore, the lesser extent of primary emotions was particularly marked for nondiagnosed individuals, F(1, 2248) = 17.54, P < .001.

To explore this unexpected pattern in more detail, difference scores were calculated for each emotion in a way that positive scores reflected that Hans was seen as more likely to experience this emotion whereas negative scores indicated a reduced likelihood of Hans experiencing this emotion (compared to the self). The overall mean values of these difference scores suggested that Hans was expected to have markedly less positive emotions but slightly more negative emotions (figure 1).

Exploratory analyses were conducted to test whether the schizophrenia diagnosis affected the ascription of separate emotions to Hans (Bonferroni-adjusted for 14 comparisons: P = .0035). Mentioning schizophrenia led to a greater estimated likelihood of Hans experiencing rage, t(2248) = 3.64, P < .001, d = 0.15; anger, t(2248) = 4.74, P < .001, d = 0.20; shame, t(2248) = 2.96, P = .003, d = 0.12, and surprise, t(2217.77) = 3.86, P < .001, d = 0.16. Particularly, the first 2 align well with the emerging stereotype of an unpredictably impulsively aggressive patient, already observed for the social perception items.

Finally, it was tested whether the subtle introduction of schizophrenia altered responses on the Mental Illness Stigma Scale by subjecting its subscales to 7 independent t tests (Bonferroni-corrected P = .007). Respondents in the schizophrenia condition reported to feel more anxious in Hans’ presence and to expect (marginally) more relationship disruption (table 2). Mirroring the lack of an effect on the single item “dirty,” the diagnosis did not reduce the expected level of personal hygiene. Calling Hans’ condition schizophrenia made it drastically less visible in respondents’ opinion but at the same time increased the treatability and decreased the chances of recovery. Thus, although participants felt there existed effective ways of treating schizophrenia (vs the undiagnosed collection of symptoms), these are seen as ineffective in ever getting fully functional again.

Table 2.

Mean Scores on 7 Subscales of Day’s Mental Illness Stigma Scale 37 as a Function of Schizophrenia Label

| Schizophrenia (n = 1102) | No-Diagnosis (n = 1148) | Group Differences | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item # | Α | M | SD | M | SD | T | d | |

| Anxiety | 7 | 0.89 | 2.57 | 1.10 | 2.35 | 0.97 | 5.01* | 0.21 |

| Relationship disruption | 6 | 0.76 | 3.63 | 1.08 | 3.51 | 1.02 | 2.65† | 0.11 |

| Hygiene | 4 | 0.89 | 3.05 | 1.26 | 3.14 | 1.29 | −1.52 | −0.06 |

| Visibility | 4 | 0.79 | 3.66 | 1.19 | 4.13 | 1.12 | −9.66* | −0.41 |

| Treatability | 3 | 0.53 | 4.90 | 1.02 | 4.75 | 1.05 | 3.28* | 0.14 |

| Professional efficacy | 2 | 0.85 | 5.01 | 1.30 | 5.10 | 1.30 | −1.78 | −0.08 |

| Recovery | 2 | 0.77 | 5.06 | 1.40 | 5.44 | 1.27 | −6.81* | −0.29 |

Note: Across experimental conditions, all items referred directly to “people like Hans H.” (in the original scale these passages read “someone with [mental illness]”). All items completed on a scale from 1 (do not agree at all) to 7 (fully agree).

*P < .007; † P = .008.

Personal Involvement

In total, 412 participants reported to have suffered from a psychological condition (2 named schizophrenia), independent of experimental condition, χ2(1) = 1.09, P = .30. The majority of participants, n = 1456, reported to have someone in their immediate environment who had suffered from a psychological condition, also independent of experimental condition, χ2(1) = 0.70, P = .40 (148 named schizophrenia). To test whether personally involved persons (either own suffering or someone in their close surroundings) would be less prone to labeling effects, two sets of ANOVAs were run with the experimental condition, the two forms of personal experience and their respective interaction as factors, and all variables as criteria. Overall, the two facets of personal involvement had a number of main effects but never interacted with the experimental condition.

Discussion

The results clearly show a nuanced albeit consistent effect of a diagnostic label (“schizophrenia”) on the social perception of a patient suffering from symptoms that are sufficient to allow such a diagnosis. The diagnosed individual was seen as more aggressive, less faithful, and more creative, which might be the reason why participants also anticipated experiencing more anxiety in the presence of the person. As another aspect, the diagnosis seems to have mystified the symptomatology, as despite having the exact same symptoms in both conditions, introducing the label-reduced estimations of being able to detect the condition (visibility) and the expected chance of recovery.

Importantly, all described effects were small, suggesting that recruiting a large sample for a high-powered test of the labeling hypothesis is necessary to actually detect effects of this size. Because there were no clear-cut a priori predictions on which variables labeling effects were expected, all statistical tests were adjusted for multiple testing. Thus, despite the small effect size, we are confident that the observed effects are real and reliable. The exact same behavior and symptoms will be evaluated and interpreted differently if called schizophrenia. Although this assumption is so widespread that it has almost reached the status of a cultural truism, previous research that experimentally manipulated presence vs absence of diagnostic labels consistently failed to find an effect.16,27–29 The present findings thus provide substance to the modified labeling approach18 even though labeling effects might often be overlooked due to their modest size or suppression by antagonist effect.41 They also allow a nuanced view on which kind of perceptions are mostly affected and which are not. Although Hans was seen as more aggressive and less trustworthy, his sincerity, warmth, and likeability remained intact. Maybe even more remarkable, there was no indication of infrahumanization in either condition. One the one hand, there is hope that “schizophrenia” does not boost stigmatization on all fronts, on the other hand it has to be conceded that the manipulation was subtle and provided a very conservative test. Even in the no-diagnosis condition, Hans was described as a patient seeing a psychiatrist after being referred by a medical doctor, which might already provoke some degree of stigmatization compared to a person with the same symptomatology but no role as a healthcare customer. In summary, the findings provide neither reason to be alarmed (due to the relatively modest effect size) nor to be apathetic (after all, labeling effects on social perception are real). People do use schizophrenia as a cue to aggressive and hostile behavior and will thus likely exhibit more social rejection towards the carriers of such a diagnosis. This may be one the underlying processes of the well-documented negative effect of diagnoses on the carriers.18

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the present research clarifies an important issue on a solid empirical base, there remain some limitations. First of all, the symptoms used to describe Hans H.’s condition intentionally did not include hallucinations or delusions, arguably the 2 symptoms most strongly associated with schizophrenia in the layperson’s mind. Mentioning such symptoms would have increased the chances that participants self-generated the diagnosis that was sought to be manipulated. Importantly, the symptoms included in the case were fully sufficient to diagnose schizophrenia according to DSM-5 nevertheless. What the current data do not tell us is the underlying processes of the obtained labeling effect. It is conceivable that the term “schizophrenia” alone evokes associations with violent and hostile behavior, which fits well with everyday usage of “schizophrenia,” and particularly “schizophrenic” in a negative and sarcastic manner.42 Alternatively, however, it may also be that the label activates a knowledge structure that is wider in its connotation than the mentioned symptoms. Thus, reading that the patient suffers from schizophrenia might bring participants to (falsely) conclude that he must then also have hallucinations and delusions, which is consequently used as a cue to aggressive behavior.

Calling someone “schizophrenic” has negative effects on other people’s perception of this person. Seeking effective ways to combat such stigma has led some scholars to suggest renaming the diagnosis43–45 (eg, as “salience syndrome”45), which might also accommodate the wishes of symptom carriers.46,47 Although such a strategy might indeed alleviate stigma (but see Tranulis et al46), merely changing the name will be effectual only as long as the new term does not carry the same connotations as the old one previously did.48 Such very ambitious interventions thus run the risk of having only temporary effects. As an alternative, interventions should target the very core of stigmatizing reactions: the associations of schizophrenia with dangerousness. Whether public campaigns can be an effective way to change public perceptions of schizophrenia even against the backdrop of a pervasive cultural stereotype of the “violent lunatic” is open to future research.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Gregory Heuser for data collection. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N, Leese M; INDIGO Study Group. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2009;373:408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farina A. Stigma. In: Mueser K. T., Tarrier N. Eds. Handbook of Social Functioning in Schizophrenia. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1998:247–279 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Phelan JC, Link BG. Fear of people with mental illnesses: the role of personal and impersonal contact and exposure to threat or harm. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45:68–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brockington IF, Hall P, Levings J, Murphy C. The community’s tolerance of the mentally ill. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crisp A, Gelder M, Goddard E, Meltzer H. Stigmatization of people with mental illnesses: a follow-up study within the Changing Minds campaign of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. World Psychiatry. 2005;4:106–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Durand-Zaleski I, Scott J, Rouillon F, Leboyer M. A first national survey of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours towards schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and autism in France. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levey S, Howells K. Dangerousness, unpredictability and the fear of people with schizophrenia. J Forensic Psychiatr. 1995;6:19–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1328–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Link BG, Cullen FT. Contact with the mentally ill and perceptions of how dangerous they are. J Health Soc Behav. 1986;27:289–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Penn DL, Kommana S, Mansfield M, Link BG. Dispelling the stigma of schizophrenia: II. The impact of information on dangerousness. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wright A, Jorm AF, Mackinnon AJ. Labeling of mental disorders and stigma in young people. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wahl OF. Media Madness: Public Images of Mental Illness. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scheff TJ. Being Mentally Ill: A Sociological Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scheff TJ. The labelling theory of mental illness. Am Sociol Rev. 1974;39:444–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gove WR. The Labelling of Deviance: Evaluating a Perspective. Thousand Oaks,CA: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirk SA. The impact of labeling on rejection of the mentally ill: an experimental study. J Health Soc Behav. 1974;15:108–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weinstein RM. Labeling theory and the attitudes of mental patients: a review. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:70–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. Am Sociol Rev. 1989;54:400–423. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Penn DL, Nowlin-Drummond A. Politically correct labels and schizophrenia: a rose by any other name? Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Graves RE, Cassisi JE, Penn DL. Psychophysiological evaluation of stigma towards schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;76:317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Graf J, Lauber C, Nordt C, Rüesch P, Meyer PC, Rössler W. Perceived stigmatization of mentally ill people and its consequences for the quality of life in a Swiss population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:542–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Link B. Mental patient status, work, and income: an examination of the effects of a psychiatric label. Am Sociol Rev. 1982;47:202–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52:96 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Link BG, Mirotznik J, Cullen FT. The effectiveness of stigma coping orientations: can negative consequences of mental illness labeling be avoided? J Health Soc Behav. 1991;32:302–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. The stigma of mental illness: effects of labelling on public attitudes towards people with mental disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108:304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yap MB, Reavley N, Mackinnon AJ, Jorm AF. Psychiatric labels and other influences on young people’s stigmatizing attitudes: findings from an Australian national survey. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boisvert CM, Faust D. Effects of the label “schizophrenia” on causal attributions of violence. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kirmayer LJ, Fletcher CM, Boothroyd LJ. Inuit attitudes toward deviant behavior: a vignette study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schwartz S, Weiss L, Lennon MC. Labeling effects of a controversial psychiatric diagnosis: a vignette experiment of late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. Women Health. 2000;30:63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fiske ST, Cuddy AJ, Glick P. Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kyaga S, Lichtenstein P, Boman M, Hultman C, Långström N, Landén M. Creativity and mental disorder: family study of 300,000 people with severe mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martinez AG, Piff PK, Mendoza-Denton R, Hinshaw SP. The power of a label: mental illness diagnoses, ascribed humanity, and social rejection. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leyens J, Paladino PM, Rodriguez-Torres R, et al. The emotional side of prejudice: the attribution of secondary emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2000;4:186–197. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leyens J, Rodriguez-Perez A, Rodriguez-Torres R, et al. Psychological essentialism and the differential attribution of uniquely human emotions to ingroups and outgroups. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2001;31:395–411. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bilewicz M, Imhoff R, Drogosz M. The humanity of what we eat: Conceptions of human uniqueness among vegetarians and omnivores. Eur J So Psychol. 2011;41:201–209. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Demoulin S, Leyens J, Paladino M, Rodriguez‐Torres R, Rodriguez‐Perez A, Dovidio J. Dimensions of “uniquely” and “non‐uniquely” human emotions. Cogn Emot. 2004;18:71–96. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Day EN, Edgren K, Eshleman A. Measuring stigma toward mental illness: development and application of the mental illness stigma scale. J Appl Social Pyschol. 2007;37:2191–2219. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kolodziej ME, Johnson BT. Interpersonal contact and acceptance of persons with psychiatric disorders: a research synthesis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1387–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mayville E, Penn DL. Changing societal attitudes toward persons with severe mental illness. Cogn Behav Pract. 1998;5:241–253. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Phelan JC, Link BG, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness in 1950 and 1996: what is mental illness and is it to be feared? J Health Soc Beh. 2000;41:188. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Imhoff R. Punitive attitudes against pedophiles or persons with sexual interest in children: does the label matter? Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44:35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Joseph AJ, Tandon N, Yang LH, et al. #Schizophrenia: use and misuse on Twitter. Schizophr Res. 2015;165:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Keshavan MS, Tandon R, Nasrallah HA. Renaming schizophrenia: keeping up with the facts. Schizophr Res. 2014;148:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lasalvia A, Penta E, Sartorius N, Henderson S. Should the label “schizophrenia” be abandoned? Schizophr Res. 2015;162:276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van Os J. ‘Salience syndrome’ replaces ‘schizophrenia’ in DSM-V and ICD-11: Psychiatry’s evidence-based entry into the 21st century? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120:363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tranulis C, Lecomte T, El-Khoury B, Lavrenne A, Brodeur-Côté D. Changing the name of schizophrenia: patient perspectives and implications for DSM-V. PLos ONE. 2013, 8: e55998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Essock SM, Rogers L. What’s in a name? Let’s keep asking. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:469–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lieberman JA, First MB. Renaming schizophrenia. BMJ. 2007;334:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]