Abstract

Objective: The study objective was to examine factors that influence African American (AA) family members' end-of-life care decision outcomes for a relative who recently died from serious illness.

Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive study design was used. Binary logistic and linear regressions were used to identify factors associated with decision regret and decisional conflict. Forty-nine bereaved AA family members of AA decedents with serious illness who died two to six months prior to enrollment were recruited from the palliative care program in a safety net hospital and a metropolitan church in the Midwest. Measurements used were the Decisional Conflict, Decision Regret, Beliefs and Values, and Quality of Communication scales.

Results: Family members who reported higher quality of communication with health care providers had lower decisional conflict. Family members of decedents who received comfort-focused care (CFC) had significantly less decision regret than family members of those who received life-prolonging treatment (LPT). Family members who reported stronger beliefs and values had higher quality of communication with providers and lower decisional conflict.

Conclusions: This research adds to a small body of literature on correlates of end-of-life decision outcomes among AAs. Although AAs' preference for aggressive end-of-life care is well-documented, we found that receipt of CFC was associated with less decision regret. To reduce decisional conflict and decision regret at the end of life, future studies should identify strategies to improve family member–provider communication, while considering relevant family member and decedent characteristics.

Introduction

African Americans' (AA) tendency to choose life-prolonging treatments over comfort-focused care at the end of life is well documented.1–6 However, AA experiences with end-of-life decision making and factors that influence the decision to select life-prolonging treatments over comfort-focused care are not well understood. Evidence suggests the factors that affect AA end-of-life decision making are multifaceted and include patient and family member characteristics, as well as the interaction between patients, family members, and health care providers (HCPs). Communication is a critical component underlying these factors.7–9

Communication is a central component of patient and family member–centered care.10 Some AA patients prefer patient and family-centered care,7,11–13 wherein they and their caregivers are actively involved in medical decision making, participate in discussions about treatment options, and give feedback about decisions.12–14 Family members play an integral role in end-of-life decision making,15 especially among AA patients;7,11–13 however, many patients and family members experience poor communication with HCPs regarding end-of-life treatments.7,16–18 Effective end-of-life communication has reduced end-of-life care resource use, shortened hospital stays, lowered intensive care unit mortality rates and costs, and increased use of comfort-focused care.19,20 To provide effective and cost-efficient care at the end of life, it is essential to improve patient–family member–provider communication and better understand end-of-life decision making among AAs with serious illnesses and their family members.14,19–21

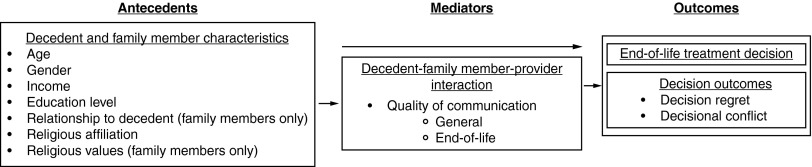

The purpose of this study was to examine factors that influenced AA family members' end-of-life care decision making for a relative who recently died with serious illness. A conceptual framework, informed by the literature and the Ottawa Decision Support Framework, was developed to guide this study (see Fig. 1). The main outcomes examined included end-of-life treatment decision (life-prolonging treatments or comfort-focused care), decision regret, and decisional conflict.22–26 Study objectives were the following:

1) Describe bereaved family members' quality of communication with health care providers, end-of-life treatment decision, and decision outcomes (decision regret and decisional conflict).

2) Examine if decedents' and bereaved family members' characteristics correlate with quality of communication with health care providers.

3) Examine the correlates of end-of-life treatment decision (comfort-focused care or life-prolonging treatment) in this sample of bereaved AA family members.

4) Investigate if decedents' characteristics, family members' characteristics, and quality of communication with health care providers predict decision outcomes (decision regret and decisional conflict).

FIG. 1.

African American end-of-life decision making conceptual framework.

Methods

Setting and sample

This study was approved by the Indiana University institutional review board. A convenience sample of 49 AA bereaved family members of AAs who died between two and six months prior to enrollment were recruited to participate. The investigators chose a window of two to six months to take advantage of family members' recall of recent events, while also being sensitive to their emotional well-being. Eligibility criteria for family members included being age 21 years or older; self-described as AA; related to the decedent by blood, marriage, or other close affiliation; agreed he or she was somewhat (i.e., made some decisions) or very involved (i.e., made many decisions) in decedent's care and/or decision making in the last month of life; and able to speak and read English. Eligibility criteria for decedents included being age 21 years or older; being identified as AA in the medical chart; having received either comfort-focused care or life-prolonging treatments at a health care institution; and a death due to complications of a serious illness (i.e., cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and congestive heart failure) within the past two to six months. Bereaved family members were recruited from two locations in the Midwest: A palliative care program in a 315-bed safety net county hospital, which serves poor and minority populations (n = 44); and a large, predominately AA church (n = 5).

Procedures

To recruit bereaved family members from the palliative care program, eligible decedents and decedents' bereaved family members (those listed as next of kin) were identified using the program's patient database. Each identified family member was mailed an introductory letter from the palliative care program medical director; an information sheet describing the potential risks, benefits, and alternatives to participation; as well as a brochure explaining the study. The introductory letter included a telephone number for family members to call if they were not interested in being contacted about the study. Family members who had not opted out were contacted by phone one week after study packets were mailed. During this phone call the investigator described the study, answered questions, determined eligibility, and invited participation.

Recruitment procedures were different at the church at the request of church leadership. To recruit church members, the investigator (ESH) made a recruitment announcement to church members who attended a monthly Senior Saints meeting, intended for members 65+ years. Church members received a description of the study (including eligibility criteria), study information sheets, and brochures. After answering questions, those who expressed interest in participating were asked to provide their names and phone numbers in order to complete a one-time telephone interview. Those who provided contact information were called by the investigator to determine eligibility, answer questions, and obtain verbal consent. Data were collected by telephone.

Measures

Each interview was guided by a script. Decedents' and family members' characteristics were assessed using an investigator-developed demographic survey, which included age, gender, income, education level, relationship to decedent, and religious affiliation. Religious values of AA family members were assessed using the Beliefs and Values Scale26 (Cronbach α = 0.905). This 20-item scale measured spiritual and religious beliefs using a five-point Likert response option, where 0 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree. To compute scores, each item was summed. Possible scores ranged from 0 to 80, with higher scores indicating stronger spiritual and religious beliefs.26

Quality of communication with HCPs was measured using the Quality of Communication Scale.27 The overall Quality of Communication Scale is comprised of two subscales: the Quality of General Communication Subscale (items 1–6) (Cronbach α = 0.938) and the Quality of End-of-life Communication Subscale (items 7–13) (Cronbach α = 0.863). Sample items of the Quality of Communication Scale include: “How good was the health care team at using words you understood?” and “How good was the health care team at talking about what dying might be like?” Response options ranged from 0 to 10, with 0 = “poor,” 5 = “very good,” and 10 = “absolutely Pperfect.”27 Response options also included “The health care team didn't do this” = 0 or “I don't know” = missing.

Comfort-focused care was defined as, “Care offered to those patients with advanced and life-threatening illness who may or may not be enrolled in a hospice or palliative care program, who have refused life-prolonging treatment, and who may be receiving care in a variety of settings, including a home, hospital, nursing home, long-term care facility, or hospice.”1,28–30 Life-prolonging treatment was defined as, “Treatment that prolongs life without reversing the underlying medical condition (i.e., mechanical ventilation, renal dialysis, chemotherapy, antibiotics, and artificial nutrition and hydration.”31 End-of-life treatment decision was measured using an investigator-developed question: “In the last month of life, was the goal of your loved one's treatment focused on keeping him or her comfortable or more towards trying to cure him or her of the illness?” Two categorical response options were ‘comfort-focused care’ or ‘life-prolonging treatment.’

Decision regret was measured using the Ottawa Decision Support (ODS) Decision Regret Scale22 (Cronbach α = 0.750). This five-item scale measured decision regret using a five-point Likert response option, where 1 = “strongly agree” and 5 = “strongly disagree.” To compute total scores, one was subtracted from each item total and multiplied by 25. Scores ranged from 0 (no regret) to 100 (high regret).32

Decisional conflict was measured by the ODS Decisional Conflict Scale (Cronbach α = 0.853).24 The Decisional Conflict Scale measures personal perceptions of (1) uncertainty in choosing options; (2) amendable factors influencing uncertainty such as feeling uninformed, unclear about personal values, and unsupported in decision making; and (3) effective decision making such as feeling the choice is informed, values-based, and likely to be implemented, as well as expressing satisfaction with the choice.24 The 10-item scale measured decisional conflict using questions with three response options, ‘yes’ = 0, ‘no’ = 4, and ‘unsure’ = 2.24 To compute the total decisional conflict score, the scale's 10 items were summed, divided by 10, and multiplied by 25. Possible decisional conflict scores ranged from 0 (no decisional conflict) to 100 (extremely high decisional conflict).

Data analysis

Shapiro-Wilk tests (p < 0.05) and visual inspections of histograms, normal Q-Q plots, and box plots of all measures showed that none of the measures were normally distributed with the exception of the Quality of End-of-Life Communication Scale. The Decision Regret and Values and Belief Scales were square-root transformed to achieve normality in linear regression analyses. The Decisional Conflict and Quality of General Communication Scales were dichotomized at the median due to nonnormality for logistic regression analyses. The General Communication Scale was dichotomized at the median of 8.83. The dichotomized values were “poor communication” (0–8.83) and “good communication” (8.83–10). “Poor communication” was represented by the quality of general communication scores of 24 participants and “good communication” was represented by the quality of general communication scores of 25 participants. The Decisional Conflict Scale was dichotomized at the median of 20. The dichotomized values were “no conflict to little conflict” (0–20) and “moderate conflict to high conflict” (21–100). “No conflict to little conflict” was represented by the decisional conflict scores of 30 participants, and “moderate conflict to high conflict” was represented by the decisional conflict scores of 19 participants.

To address Objective 1, descriptive statistics (mean and SD) and frequencies were performed on bereaved family members' quality of communication, end-of-life treatment decision, and decision outcomes. For Objective 2, Mann-Whitney U tests, t-tests, Spearman correlations, and Pearson correlations were used. For Objectives 3 and 4, logistic (for end-of-life treatment decision and decisional conflict) and linear regressions (for decision regret) were performed. Due to the exploratory nature of these analyses, no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. All statistical tests were considered significant at a priori alpha level α = 0.05. In the multiple regression models we included any factors that were potentially associated with the outcome (p ≤ 0.250). Family member (including general and end-of-life communication) and decedent factors were modeled separately in multivariable analyses due to the small sample size. The number of covariates entered in multivariable logistic regressions was limited to two; and for multivariable linear regressions, the number of covariates was three or less.

Results

Decedent and family member characteristics are reported in Table 1. The majority of family members (67.3%) were female. More than half were sons or daughters of the decedent (55.4%). Family members held strong religious beliefs and values (M = 64.63, SD = 10.4). Posthoc analysis revealed that female decedents (M = 72.42) were significantly older than male decedents (M = 65.08; t(47) = –2.21, p = 0.032).

Table 1.

Family Members' and Decedents' Characteristics

| Total sample (n = 49) | Total sample (n = 49) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Family members | Decedents | ||

| Age | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| 0–34 | 2 | (4.1) | - | |

| 35–49 | 19 | (38.8) | 4 | (8.2) |

| 50–64 | 19 | (38.8) | 14 | (28.6) |

| 65–79 | 8 | (16.3) | 22 | (44.9) |

| 80+ | 1 | (2.0) | 9 | (18.4) |

| M (SD) | 52.3 | (12.0) | 68.7 | (12.1) |

| Range | 29–81 | 38–95 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 16 | (32.7) | 25 | (51.0) |

| Female | 33 | (67.3) | 24 | (49.0) |

| Annual incomea | ||||

| $30,000 or less ($15,000 or less for decedents) | 23 | (48.9) | 22 | (48.9) |

| More than $30,000 (More than $15,000 for decedents) | 24 | (51.1) | 23 | (46.9) |

| Education (grade)a | ||||

| High school or less | 13 | (26.5) | 32 | (71.1) |

| Postsecondary school | 36 | (73.5) | 13 | (28.9) |

| Religious affiliationa | ||||

| Christian | 47 | (95.9) | 46 | (97.9) |

| None | 2 | (4.1) | 1 | (2.1) |

| Religious beliefs and values M (SD) | 64.6 | (10.4) | ||

| Relationship to decedent | ||||

| Husband | 2 | (4.1) | ||

| Wife | 5 | (10.2) | ||

| Daughter or stepdaughter | 15 | (30.6) | ||

| Son or stepson | 12 | (24.5) | ||

| Daughter-in-law | 4 | (8.2) | ||

| Sister | 5 | (10.2) | ||

| Brother | 2 | (4.1) | ||

| Niece | 1 | (2.0) | ||

| Other relative | 1 | (2.0) | ||

| Friend | 2 | (4.1) | ||

Missing values were due to family members' refusals or lack of knowledge to answer.

Describe bereaved family members' quality of communication with health care providers, end-of-life treatment decision, and decisional outcomes (decision regret and decisional conflict)

Family members reported high quality of general communication (M = 8.07, SD = 2.13), but somewhat lower quality of end-of-life communication with HCPs (M = 5.99, SD = 2.78). A majority (63.3%) of decedents received comfort-focused care versus life-prolonging treatments (36.7%). Family members reported relatively low decision regret (M = 22.24, SD = 17.77) and decisional conflict (M = 25.41, SD = 26.24), indicating many family members did not feel uncertain about nor did they regret the choices made for decedents' care.

Examine if decedents' and bereaved family members' characteristics correlate with quality of communication with health care providers

Quality of general communication scores were higher for family members of female decedents (Mdn = 30.12) than those of male decedents (Mdn = 20.08; U = 177.00, p = 0.013). Likewise, quality of end-of-life communication scores were higher for family members of female decedents (M = 6.85) than those of male decedents (M = 5.17; t(47) = –2.19, p = 0.033). Bivariate correlation showed that higher ratings of quality of general (p = 0.043) and end-of-life communication scores (p = 0.030) were positively associated with family member age. Family members' end-of-life communication scores were also positively associated with decedent age (p = 0.028) through bivariate correlation. Bivariate correlation showed that family members' quality of general communication scores were positively associated with religious values scores (p = 0.026).

Examine the correlates of end-of-life treatment decision (comfort-focused care or life-prolonging treatment) in this sample of bereaved African American family members

Decision regret scores were significantly higher in family members of decedents who received life-prolonging treatments (M = 5.07, SD = 2.20) versus those of decedents who received comfort-focused care (M = 3.65, SD = 2.09; t(47) = –2.24, p = 0.030). There were no significant relationships between decedents' characteristics, family members' characteristics, or quality of communication (general and end-of-life) with end-of-life treatment decision.

Investigate if decedents' characteristics, family members' characteristics, and quality of communication with health care providers predict decision outcomes (decision regret and decisional conflict)

No decedent variables predicted decisional conflict (models not shown). Multivariable logistic regression showed that family members who reported lower quality of general (p = 0.030) and end-of-life (p = 0.014) communication were more likely to have higher decisional conflict scores in multivariable logistic regression models (see Table 2). Quality of general (p = 0.777) and end-of-life (p = 0.484) communication multivariable models had good fit based on Hosmer-Lemeshow tests. Nagelkerke's R2 indicated that the quality of general and end-of-life communication multivariable models explained 23.0% and 29.0% of the variance in family members' decisional conflict scores, respectively. Although not significant in the logistic regression models, posthoc correlational analysis indicated religious values scores were negatively correlated with family members' untransformed decisional conflict scores (i.e., not dichotomized) via Spearman bivariate correlation (p = 0.047). Lastly, multivariable linear regression analysis showed that being the family member of a male decedent was predictive of more decision regret (p = 0.022) (see Table 3). There were no other significant relationships between decedents' characteristics, family members' characteristics, or quality of communication with decision outcomes (see Table 4).

Table 2.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Analyses: Family Members' Characteristics and Family Members' Quality of Communication Scores (General and End-of-Life) as Predictors of Family Members' Decisional Conflict Scores

| Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Covariate | B | SE | p | Exp (B) |

| Decisional conflict | Quality of general communication | −1.47 | 0.68 | 0.030 | 0.23 |

| Family member age | −0.35 | 0.03 | 0.242 | 0.97 | |

| Family member gender | |||||

| Family member income | |||||

| Family member education | |||||

| Family member religious values | |||||

| R2 | 0.23 | ||||

| n | 49 | ||||

| Decisional conflict | Quality of end-of-life communication | −0.34 | 0.14 | 0.014 | 0.71 |

| Family member age | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.286 | 0.97 | |

| Family member gender | |||||

| Family member income | |||||

| Family member education | |||||

| Family member religious values | |||||

| R2 | 0.29 | ||||

| n | 49 | ||||

The dependent variable in this analysis is decisional conflict coded so that 0 = “Little to no conflict” and 1 = “Moderate to high conflict. “The healthcare team didn't do this” was coded as a rating of 0. “I don't know” was coded as missing. The subscales: the General Communication Subscale (items 1–6) and the End-of-life Communication Subscale (items 7–13) had response options that ranged from 0 = “poor” to 10 = “absolutely perfect.” The middle of the scale with the value of 5 = “very good.”27

Table 3.

Linear Multivariable Regression Analyses: Decedents' and Family Members' Characteristics and Family Members' Quality of General Communication Scores as Predictors of Family Members' Decision Regret Scores

| Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Covariate | B | SE | p |

| Decision regret | Decedent age | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.457 |

| Decedent gender | −1.49 | 0.63 | 0.022 | |

| Decedent income | ||||

| Decedent education | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.11 | |||

| F | 4.02 | |||

| Decision regret | Quality of general communication | 5.68 | 1.08 | 0.203 |

| Family member age | ||||

| Family member gender | ||||

| Family member income | ||||

| Family member education | ||||

| Family member religious values | −0.24 | 0.24 | 0.335 | |

“The health care team didn't do this” was coded as a rating of 0. “I don't know” was coded as missing. The subscales: the General Communication Subscale (items 1–6) and the End-of-life Communication Subscale (items 7–13) had response options that ranged from 0 = “poor” to 10 = “absolutely perfect.” The middle of the scale with the value of 5 = “very good.”27

Table 4.

Linear Univariate Regression Analyses: Family Members' Characteristics and Family Members' Quality of End-of-Life Communication Scores as Predictors of Family Members' Decision Regret Scores

| Univariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Covariate | B | SE | p |

| Decision regret | Quality of end-of-life communication | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.698 |

| Family member age | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.704 | |

| Family member gender | −0.46 | 0.68 | 0.498 | |

| Family member income | −0.70 | 0.65 | 0.288 | |

| Family member education | 0.08 | 0.73 | 0.917 | |

| Family member religious values | −0.34 | 0.23 | 0.147 | |

“The healthcare team didn't do this” was coded as a rating of 0. “I don't know” was coded as missing. The subscales: the General Communication Subscale (items 1–6) and the End-of-life Communication Subscale (items 7–13) had response options that ranged from 0 = “poor” to 10 = “absolutely perfect.” The middle of the scale with the value of 5 = “very good.”27

Discussion

To the research team's knowledge this is the only study to assess quality of communication, decision regret, and decisional conflict of bereaved AA family members. An important finding of bivariate correlation analysis showed that family members' quality of general and end-of-life communication were negatively associated with decisional conflict. These findings suggest that when AA bereaved family members experience poor quality of general and end-of-life communication with HCPs, family members feel more uncertain about end-of-life decisions.

Several other studies have found negative associations between decisional conflict and patients' knowledge, satisfaction with information, and shared decision making;33–35 however, this study's focus on the relationship between decisional conflict and the quality of communication in AA family members is unique. Overwhelming evidence, little of which represents AA experiences, suggests that decision making and decisional conflict for patients with serious illnesses and their families are impacted by factors including knowledge about diagnosis, treatment options, treatment outcomes, and information received from HCPs.33–38

Communication is a critical component of end-of-life decision making among AAs and their families.39 The findings from several studies suggest that AAs have limited knowledge regarding some life-prolonging treatments40–42 and do not seek this knowledge out.43 Furthermore, AAs often do not choose comfort-focused care, because they have limited knowledge of hospice and advance directives.44 When given adequate information regarding all possible treatment options (life-prolonging treatments and comfort-focused care), AAs have chosen comfort-focused care more often and experienced less decisional conflict.42 This information suggests that decisional conflict is a modifiable construct. Since AAs' decisional conflict has been reduced by giving adequate information in a previous study, plausibly, quality of communication can be modified to reduce decisional conflict as well. It is important to note that quality of general and end-of-life communication multivariable logistic models explained only 23% and 29% of the variance in family members' decisional conflict scores, respectively. These findings indicate that there are other variables that could provide further explanation of family members' decisional conflict.

Family members of decedents who received comfort-focused care had significantly less decision regret than those of decedents who received life-prolonging treatments. This finding is unique, because it is the first study to suggest that AA family members may regret choosing life-prolonging treatment versus comfort-focused care. This finding is consistent with the findings of other studies, which were conducted in non-AA samples. Evidence in other studies suggest that do-not-resuscitate orders predicted better mental health for family members.45 Additionally, bereaved caregivers' quality of life has been positively associated with comfort-focused care and negatively associated with regret.46 Other studies have demonstrated that bereaved family members had less regret when decedents died peacefully.47 Furthermore, better quality of patients' deaths reduced the risk of regret, as well as improved quality of life for bereaved family members.45 This study's findings, along with that of other studies, suggest that family members of decedents who received comfort-focused care were better able to accept their end-of-life care decisions. Conversely, the family members of decedents who continued life-prolonging treatments were more likely to regret these decisions.

While multivariable linear findings of this study show that family members of male decedents experienced more decision regret than those of female decedents, the research team found no other study that associated gender with decision regret. The difference in family members' decision regret by decedent gender may be explained by other findings of this study that showed family members of female decedents reported higher quality of general and end-of-life communication than those of male decedents. Similarly, other investigators found family members of male decedents were less satisfied with their communication with HCPs than those of female decedents.48 These investigators offered no explanation for this gender difference. Possibly, family members of male decedents in the current study experienced more decision regret than those of female decedents, because male decedents were sicker or entered the health care system with later-stage diagnoses than their female decedent counterparts. Prior research suggests that when patients enter the health care system with more severe illnesses, family members have poorer communication with HCPs, particularly if death occurs quickly.49,50 This explanation seems reasonable, since men are more likely to have serious illnesses associated with higher mortality rates, such as coronary artery disease, than women. Men also suffer from significantly higher in-hospital mortality rates than women.51

An intriguing alternative explanation for family members of male decedents having higher decision regret may be related to decedents' age. Perhaps family members had less regret for end-of-life care decisions made for older female decedents, because they experienced better end-of-life communication with HCPs regarding their care. Findings indicated that older family members had higher quality of end-of-life communication with HCPs regarding older decedents' care. Prior studies have shown that family members of the oldest patients were more satisfied with family member–provider communication,52 and family members of younger patients were at increased risk for poor comprehension of information regarding the patients' diagnoses, prognoses, and treatment options.53 These findings suggest that, perhaps, family members of older patients are better able to accept that older patients have life-limiting illnesses.54 Lastly, the sample of the current study was comprised of highly educated individuals. In fact, more than 70% of family members had received postsecondary education. Analyses did not reveal a significant relationship between family members' decision regret and their education levels. Furthermore, the authors were not able find another study that correlated participants' decision regret with their education levels.

Bivariate correlation showed that family members' religious values were positively associated with their quality of general communication with HCPs and negatively associated with decisional conflict. The former finding is consistent with another study where AAs' quality of communication was positively associated with religious beliefs.36 In addition to measuring religious beliefs and quality of communication, these investigators measured AAs' trust in HCPs and found that AAs' trust in HCPs was positively associated with their quality of communication with HCPs.36

Stronger religious values have been associated with greater trust in HCPs; trust, in turn, has been associated with higher quality of communication with HCPs. Conversely, distrust in HCPs has been associated with poorer quality of patient-provider communication.36,55 This is significant, because AAs report using religious beliefs to cope with illnesses.56 In the current study, the positive association between family members' religious values and quality of communication may have occurred because most of the family members held strong religious beliefs. Family members' strong religious beliefs may have contributed to their trust in HCPs, which improved their quality of communication with HCPs. Family members' improved quality of communication, plausibly, contributed to their reports of less decisional conflict. This study adds new information regarding the relationship between family member–provider communication and AA religious beliefs, which has been understudied.57

Lastly, this study's findings are intriguing, because they contrast existing literature regarding end-of-life treatment decisions and religion among AAs. To underscore the significance of these unique findings, existing literature asserts that AAs typically desire more life-prolonging treatments1–8 and hold stronger religious and spiritual beliefs than their white American counterparts.9–11 Furthermore, AAs with stronger religious beliefs also desire more life-prolonging treatments and are less likely to report having a living will than religious white Americans.10 In the current study, the majority of decedents (63.3%) received comfort-focused care compared to only 36.7% of those who received life-prolonging treatment. What's more, almost all (95.9%) of the family members in this study reported a Christian religious affiliation, and the sample's mean religious beliefs and values score was high (M = 64.6).

A possible explanation for a majority of decedents receiving comfort-focused care, despite highly religious family members, may be because most of the participants (90% from the palliative care program) received information regarding end-of-life care treatment options through palliative care consultations. Investigators in a previous study found that AAs were less likely than white Americans to have been exposed to information about hospice. However, when AAs were exposed to information about hospice, they had more favorable beliefs about hospice.12 Hence, it is plausible that 63.3% of decedents in the current study received comfort-focused care, because they and their family members were exposed to information about comfort-focused care, to which they responded favorably.

Another plausible explanation for the majority of decedents receiving comfort-focused care may be the result of highly educated family members aiding in end-of-life care decision making. Nearly 75% of family members in the sample had postsecondary school education, and more than half earned at least $30,000 annually. One study, with a predominately white American sample (90%), showed that income and education were significantly associated with hospice use. Specifically, individuals with lower income and education levels desired more life-prolonging treatments than those with higher income and education levels.8

Another study found significant differences between the education levels and end-of-life treatment choices between white and African American decedents. In this study, African American decedents were more likely than white American decedents to have less than a high school education, and less likely to have some college or a college degree, than white American decedents. African American decedents were also significantly less likely than white American decedents to have a living will, durable power of attorney, or have had an informal discussion of care preferences with HCPs. What's more, African American decedents were more likely to receive life-prolonging treatments than their white American decedent counterparts. The findings of the current study regarding end-of-life treatment decision among AAs are important given the amount of literature that states AAs use religious beliefs in their health care decision making, especially at the end of life. These findings serve to expand the dialogue of explanations for AA end-of-life decision making.

Limitations

One important limitation was the small sample size; since research is limited in this area, there was no statistical basis to approximate the sample size needed. A sample size of 49 allowed for good estimates of reliability of study instruments. Another limitation was the potential for selection bias. Ninety percent of the sample was recruited from a safety net hospital's palliative care program. Thus, generalizability may be limited to those who received care from a palliative care program or similar health care settings. This study also enrolled a small number of bereaved AA family members from a large metropolitan church, in the Midwest. Participants from the church may be more representative of AAs in the community who had not received care from a palliative care service. However, they represented only 10% of the study's sample. Additionally, eligible study participants were randomly selected by the investigator, which may have also introduced the potential for selection bias.

Other limitations may result from the study's design. Since this was a retrospective cross-sectional study, which captured data at one single point in time, no causality can be inferred. Additionally, since the investigator conducted telephone interviews two to six months after decedents had died, family members' perceptions of communication with HCPs may have changed over time. Specifically, through the passing of time, family members may have formed overly negative or positive perceptions of HCPs' communication patterns. Furthermore, data were collected over the telephone. Face-to-face interviews may have been a more appropriate method for gathering data about a sensitive topic such as the death of a loved one. Limitations also result from study measures. End-of-life treatment decision was assessed using an investigator-developed question rather than a validated end-of-life treatment decision question.

The study's eligibility criteria may be another limitation. To be eligible, AA bereaved family members had to speak and read English and have a telephone. This excluded participants without telephones and those with language or reading barriers. In addition, family members' involvement in decision making and/or care was assessed using an eligibility question that has been used in several previous studies;59–62 however, the question lacks clarity as to how directly family members were involved in the care and decision making process. Furthermore, due to limited access to decedent medical records, investigators were not able to provide specific information about decedents' disease severity or type of disease. Some family members provided this information, while others affirmed that the disease was serious and chronic, but refused to provide the name of the disease due to concerns about stigma.

Another limitation is that bereaved AA family members provided the data for this study. Evidence has shown family members' reports of decedents' observable symptoms have been congruent with decedent reports.63,64 However, the investigator in this study asked family members to report on their experiences in communication with HCPs and the decision to continue or discontinue life-prolonging treatments. Family members reported on their own perceptions of their and decedents' quality of communication and the decision for life-prolonging or comfort-focused care. The accuracy of their recall of decedents' perceptions and experiences was not able to be verified.

Lastly, to the authors' knowledge, this is the only study to measure quality of communication and decisional conflict jointly. Since these variables have not been assessed together in any other study, it is unknown if these findings are unique to AAs or can be replicated in samples of other ethnic and racial groups.

Conclusions

This study's findings are timely, as there is limited research exploring communication between AA family members and HCPs. Indeed, most end-of-life communication research about experiences between patients and HCPs focuses on the patient-provider relationship.65–69 The findings of this study contribute new information about AA family members' decision outcomes and quality of communication with HCPs at the end of life, while highlighting the importance of decedents' and family members' characteristics during these health care encounters. This study represents a first step in a line of research that ultimately will lead to interventions to enhance communication, as well as reduce decisional conflict and decision regret at the end of life for AAs and their families.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research Institutional Research Training Grants (1F31NR013613-01, PI Hickman; T32NR007066, PI Rawl; and T32NR009356, PI Mary Naylor); the Mary Margaret Walther Program for Cancer Care Research; Indiana University School of Nursing; Johnson & Johnson/American Association of Colleges of Nursing; Spotlight on Nursing; and Sally Tate. We are deeply grateful to the organizations that supported this research and to the family members who so generously shared their experiences.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization: NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. NHPCO, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, et al. : Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5559–5564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. : Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKinley ED, Garrett JM, Evans AT, Danis M: Differences in end-of-life decision making among black and white ambulatory cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:651–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludke RL, Smucker DR: Racial differences in the willingness to use hospice services. J Palliat Med 2007;10:1329–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazanec PM, Daly BJ, Townsend A: Hospice utilization and end-of-life care decision making of African Americans. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2010;277:560–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams SW, Hanson LC, Boyd C, et al. : Communication, decision making, and cancer: What African Americans want physicians to know. J Palliat Med 2008;11:1221–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore CD: Communication issues and advance care planning. Semin Oncol Nurs 2005;21:11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine: Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Joint Commission: Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waters CM: Understanding and supporting African Americans' perspectives of end-of-life care planning and decision making. Qual Health Res 2001;11:385–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrank WH, Kutner JS, Richardson T, et al. : Focus group findings about the influence of culture on communication preferences in end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:703–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blackhall LJ, Murphy ST, Frank G, et al. : Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA 1995;274:820–825 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell CL, Williams IC, Orr T: Factors that impact end-of-life decision making in African Americans with advanced cancer. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2010;12:214–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tschann JM, Kaufman SR, Micco GP: Family involvement in end-of-life hospital care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:835–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein RM, Street RL, Jr.: Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 17.NIH: Fact Sheet: End-of-Life. NIH, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. : Half the family members of intensive care unit patients do not want to share in the decision-making process: A study in 78 French intensive care units. Crit Care Med 2004;32:1832–1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahrens T, Yancey V, Kollef M: Improving family communications at the end of life: Implications for length of stay in the intensive care unit and resource use. Am J Crit Care 2003;12:317–323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlson RW, Devich L, Frank RR: Development of a comprehensive supportive care team for the hopelessly ill on a university hospital medical service. JAMA 1988;259:378–383 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gries CJ, Cuitis JR, Wall RJ, Engelberg RA: Family member satisfaction with end-of-life decision making in the ICU. Chest 2008;133:704–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brehaut JC, O'Connor AM, Wood TJ, Hack TF, Siminoff L, Gordon E, Feldman-Stewart D: Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making 2003;23:281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connor AM: User manual: Decision self-efficacy scale. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 1995. Available at http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Decision_SelfEfficacy.pdf (last accessed December29, 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Connor AM: User manual-decisional conflict scale. Available at http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/eval.html (last accessed October27, 2009)

- 25.O'Connor AM, Drake ER, Fiset V, et al. : The Ottawa patient decision aids. Eff Clin Pract 1999;2:163–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King M, Jones L, Barnes K, et al. : Measuring spiritual belief: Development and standardization of a Beliefs and Values Scale. Psychol Med 2006;36:417–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR: Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1086–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 2nd ed. Pittsburg, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Institute of Nursing Research: Palliative Care. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Nursing Research, 2009, p. 16 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zerwekh JV: Nursing Care at the End of Life: Palliative Care for Patients and Families. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.AMA: Opinion 2.20: Withholding or Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Medical Treatment. AMA, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brehaut JC, O'Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. : Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making 2003;23:281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen RS, Allen JY, Hilgeman MM, DeCoster J: End-of-life decision-making, decisional conflict, and enhanced information: Race effects. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1904–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Morgan S, Redman S, D'Este C, Rogers K: Knowledge, satisfaction with information, decisional conflict and psychological morbidity amongst women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Patient Educ Couns 2011;84:62–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LeBlanc A, Kenny DA, O'Connor AM, Legare F: Decisional conflict in patients and their physicians: A dyadic approach to shared decision making. Med Decis Making 2009;29:61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song L, Weaver MA, Chen RC, et al. : Associations between patient-provider communication and socio-cultural factors in prostate cancer patients: A cross-sectional evaluation of racial differences. Patient Educ Couns 2014;97:339–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Legare F, Tremblay S, O'Connor AM, et al. : Factors associated with the difference in score between women's and doctors' decisional conflict about hormone therapy: A multilevel regression analysis. Health Expect 2003;6:208–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaplan AL, Crespi CM, Saucedo JD, et al. : Decisional conflict in economically disadvantaged men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Cancer 2014;120:2721–2727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song L, Hamilton JB, Moore AD: Patient-healthcare provider communication: Perspectives of African American cancer patients. Health Psychol 2012;31:539–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwak J, Haley WE: Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist 2005;45:634–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bullock K: Promoting advance directives among African Americans: A faith-based model. J Palliat Med 2006;9:183–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen RSP, Allen JYBA, Hilgeman MMMA, DeCoster JP: End-of-life decision-making, decisional conflict, and enhanced information: Race effects. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1904–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen RS, Phillips LL, Pekmezi D, et al. : Living well with living wills: Application of Protection Motivation Theory to living wills among older Caucasian and African American adults. Clin Gerontol 2008;32:44–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA: Racial differences in self-reported exposure to information about hospice care. J Palliat Med 2009;12:921–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garrido MM, Prigerson HG: The end-of-life experience: Modifiable predictors of caregivers' bereavement adjustment. Cancer 2014;120:918–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Higgins PC, Prigerson HG: Caregiver evaluation of the quality of end-of-life care (CEQUEL) scale: The caregiver's perception of patient care near death. PLoS One 2013;8:e66066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akiyama A, Numata K, Mikami H: Importance of end-of-life support to minimize caregiver's regret during bereavement of the elderly for better subsequent adaptation to bereavement. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2010;50:175–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brazil K, Cupido C, Taniguchi A, et al. : Assessing family members' satisfaction with information sharing and communication during hospital care at the end of life. J Palliat Med 2013;16:82–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russ AJ, Kaufman SR: Family perceptions of prognosis, silence, and the “suddenness” of death. Cult Med Psychiatry 2005;29:103–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valdimarsdóttir U, Helgason ÁR, Fürst C-J, et al. : Awareness of husband's impending death from cancer and long-term anxiety in widowhood: A nationwide follow-up. Palliat Med 2004;18:432–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Corrao S, Santalucia P, Argano C, et al. : Gender-differences in disease distribution and outcome in hospitalized elderly: Data from the REPOSI study. Eur J Intern Med 2014;25:617–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewis-Newby M, Curtis JR, Martin DP, Engelberg RA: Measuring family satisfaction with care and quality of dying in the intensive care unit: Does patient age matter? J Palliat Med 2011;14:1284–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, et al. : Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med 2000;28:3044–3049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lynn J, Teno JM, Phillips RS, et al. : Perceptions by family members of the dying experience of older and seriously ill patients. Ann Intern Med 1997;126:97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaiser K, Rauscher GH, Jacobs EA, et al. : The import of trust in regular providers to trust in cancer physicians among white, African American, and Hispanic breast cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:51–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benjamins MR: Religious influences on trust in physicians and the health care system. Int J Psychiatry Med 2006;36:69–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson KS, Elbert-Avila KI, Tulsky JA: The influence of spiritual beliefs and practices on the treatment preferences of African Americans: A review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:711–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hamel RP, Lysaught MT: Choosing palliative care: Do religious beliefs make a difference? J Palliat Care 1994;10:61–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cartwright JC, Hickman S, Perrin N, Tilden V: Symptom experiences of residents dying in assisted living. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2006;7:219–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Drach LL, Perrin NA: Out-of-hospital death: Advance care planning, decedent symptoms, and caregiver burden. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:532–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fromme EK, Tilden VP, Drach LL, Tolle SW: Increased family reports of pain or distress in dying Oregonians: 1996 to 2002. J Palliat Med 2004;7:431–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tolle SW, Tilden VP, Rosenfeld AG, Hickman SE: Family reports of barriers to optimal care of the dying. Nurs Res 2000;49:310–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Addington-Hall J, McPherson C: After-death interviews with surrogates/bereaved family members: Some issues of validity. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;22:784–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McPherson C, Addington-Hall J: Judging the quality of care at the end of life: Can proxies provide reliable information? Soc Sci Med 2003;56:95–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Christakis NA: The ellipsis of prognosis in modern medical thought. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:301–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Del Vecchio Good MJ, Good BJ, Schaffer C, Lind SE: American oncology and the discourse on hope. Cult Med Psychiatry 1990;14:59–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katz J: The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Elias N: The Loneliness of the Dying. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Connors AF, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA, et al. : A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA 1995;274:1591–1598 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]