Abstract

Background:

Gingival recession is a common occurrence in periodontal disease leading to an unaesthetic appearance of the gingiva. The effect of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), when used along with double lateral sliding bridge flap (DLSBF), remains unknown. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of PRF in conjunction with DLSBF for multiple gingival recessions.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty systemically healthy individuals exhibiting Grade II gingival recession on their mandibular central incisors were recruited in this study. These patients were randomly assigned into two groups: DLSBF and PRF + DLSBF. The clinical parameters that were evaluated in this study were gingiva recession height, gingiva recession width, width of keratinized gingiva, clinical attachment level, and probing depth. PRF was procured from the patient's blood at the time of the surgery and used for the procedure. The follow-up was performed at 12 and 24 weeks postsurgery.

Results:

Statistically significant difference was observed between the clinical parameters at baseline and 12 and 24 weeks within the groups. There was no statistically significant difference, between the groups. Mean root coverage (RC) was 80% ±29.1% in the DLSBF group and 78.8% ±37.6% in the DLSBF + PRF group with no statistically significant difference.

Conclusion:

From the results obtained in this study, the addition of PRF to DLSBF gives no additional benefits to the clinical parameters measured in RC.

Keywords: Gingival recession, platelet-rich fibrin, platelet-rich plasma, root coverage

INTRODUCTION

Gingival recession is an intriguing and complex phenomenon that may present numerous therapeutic challenges to the clinician. Patients are also frequently disturbed by recession owing to sensitivity and esthetics. Gingival recession is the exposure of the root surface by an apical shift in the position of the gingival.[1]

The term “marginal tissue recession” was proposed by Maynard and Wilson in 1979[2] to indicate the exposure of root surface caused by apical migration of the soft tissue margin. The term was widely accepted because the soft tissue margin may not always be composed of the gingiva; it may even be formed only by the alveolar mucosa in some instances.

The etiology of marginal tissue recession may be high frenal pull, thin alveolar bone, abrasive and traumatic tooth brushing habits, improper restorations, gingival inflammation, dental calculus, tooth malposition, and self-mutilation or orthodontic tooth movement through a thin buccal osseous plate.

For many years, the presence of an adequate zone of the gingiva was considered to be critical for the maintenance of gingival health and for the prevention of progressive loss of connective tissue attachment. It is generally acknowledeged that an inadequate zone of gingiva would facilitate subgingival plaque formation as well as the apical spread of plaque-associated gingival lesions. The conclusion drawn from various studies is that a minimum of 2 mm keratinized gingiva is required to ensure the gingival health.[3,4,5]

If untreated, the gingival recession may progress and can compromise the prognosis of the affected tooth. Furthermore, root surface exposure may result in dentinal hypersensitivity, pain, difficult oral hygiene, root caries, abrasion, and periodontal attachment loss. Important functional points in the treatment of mucogingival problems are to stop the progressive recession process, to facilitate plaque control in the affected area, and creation of adequate vestibular depth in areas where there is a deficiency.[6,7,8]

Modalities of root coverage (RC) procedures include laterally sliding flap, double papilla flap, coronally advanced flap, epithelialized gingival graft, a subepitheial connective tissue graft, and guided tissue regeneration-based RC procedures.[9]

The double lateral sliding bridge flap (DLSBF) technique was originally proposed by Marggraf in 1985[10] to cover gingival recession, and to extend the gingiva in a one-step procedure. This technique utilizes a combination of a coronally advanced flap and the modified Edlan and Mejchar technique.[11] The advantages of this technique are that it doesn’t require a second surgical site as free soft tissue grafting procedures and a separate frenectomy procedure.

The use of polypeptide growth factors (PGF) in the periodontal regeneration has recently attracted the attention of periodontal researchers. PGFs are molecules identified in the periodontal tissues that have been implicated in the growth and differentiation of cells from the periodontal tissues. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), which is a second generation platelet concentrate, was introduced by Choukroun et al. in 2000.[12] It offers the surgeon an access to growth factors with a simple and available technology. These growth factors, which are autologous, nontoxic and nonimmunogenic, enhance, and accelerate the tissue regeneration pathways.[13,14] PRF also provides the clinician a membrane with growth factors, platelets, leukocytes, and stem cells.[14] The presence of growth factors embedded in the fibrin-mesh may initiate the periodontal regeneration.[13,15]

The aim of this study is to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of PRF in the treatment of multiple gingival recessions and in increasing the width of keratinized gingiva.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee. All subjects were required to read and sign an informed consent form explaining all the study-related procedures before inclusion in the study. Twenty subjects were randomly assigned to either study (PRF + bridge flap) or control groups (bridge flap). Randomization was performed immediately prior to surgery by drawing sealed envelopes including notes stating either “study” or “control.” Presurgical procedures were included oral hygiene instructions, full-mouth scaling and root planning, and occlusal adjustment as indicated in this study. Surgical procedures as well as PRF preparations were performed by a single investigator.

Subject recruitment

Twenty patients, ranging in age from 20 to 45 years, who reported to the Department of Periodontics, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College and Hospital, complaining of sensitivity in the lower anterior teeth were chosen for this study. A total of 40 gingival recession sites were selected from these 20 patients with two recession sites in each patient. The patients were enrolled into the study over a period of 4 months from January 2013 to April 2013.

Inclusion criteria

Mandibular anterior teeth with Miller's Class I or II recession (no loss of interdental hard and soft tissue height)

Systemically healthy subjects

Patients who were willing to comply with all study – related procedures

Patient capable of maintaining good oral hygiene.

Exclusion criteria

Previous surgical attempt to correct the gingival recession

Long-term use of antibiotics in the past 3 months

Root surface restoration

Root caries that would require restoration

History of smoking or current smokers

Systemic diseases like diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

Trauma from occlusion

Patients taking steroids or medications known to cause gingival enlargement.

Clinical parameters

The clinical parameters were all recorded using a William's periodontal probe at baseline, 12 and 24 weeks after surgery.

Probing depth (PD) was measured at three points on the custom stent (mesio-buccal, mid-buccal and disto-buccal). The measurement was made from the free gingival margin to the bottom of the sulcus

Clinical attachment loss (CAL) was measured at the same reference points used for PD. The measurement was made from the cement enamel junction (CEJ) to bottom of the sulcus

Gingival recession height (GRH) was measured by at the mid-buccal aspect of the tooth

Gingival recession width (GRW) was measured 1 mm apical to the CEJ in a mesio-distal direction

The width of the keratinized gingiva (KGW), by measuring the distance from the external projection of the base of the pocket to the mucogingival junction (MGJ). The MGJ was determined by using the rollover.

Data collection

Measuring stents for each surgical site were fabricated from self-curing orthodontic acrylic resin. Clinically reproducible measuring points were marked on the stent at the mesio-buccal, mid-buccal, and disto-buccal aspects as standardized reference points to assess the clinical parameters.

Surgical technique[11]

After a period of 4 weeks, the patients were re-evaluated and the surgical procedure was performed under local infiltration of 2% lidocaine combined with 1:100,000 epinephrine. The bridge flap technique is a combination of the coronally repositioned flap (CRF) and a modified vestibuloplasty procedure.

The first incision is arc-shaped with a distance to the vestibule of approximately 2 × GR + 2 mm. This is necessary to produce a sufficiently wide bridging flap ensuring a sufficient blood supply

A full thickness flap is elevated in a coronal direction, and an incision into the periosteum is placed at its base

This flap is elevated in a corono-apical direction after a sulcular incision

The exposed root surface was thoroughly planed using curettes

Patients in the test group received PRF over the root surfaces while those in the control group received no further treatment

The whole bridge flap is coronally repositioned to cover the denuded root surface. Sling sutures were placed with 4-0 black silk sutures to secure the flap coronally

The flap is pressed to the alveolar bone for at least 3 min to avoid hematoma

Periodontal dressing – COE-PACK™ (GC America, Alsip, IL, USA) was placed in the surgical site for a period of 1-week

The donor area was left to granulate and heal by secondary intention after the flap was coronally positioned.

Illustrations of the surgical procedures for the control and test group are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

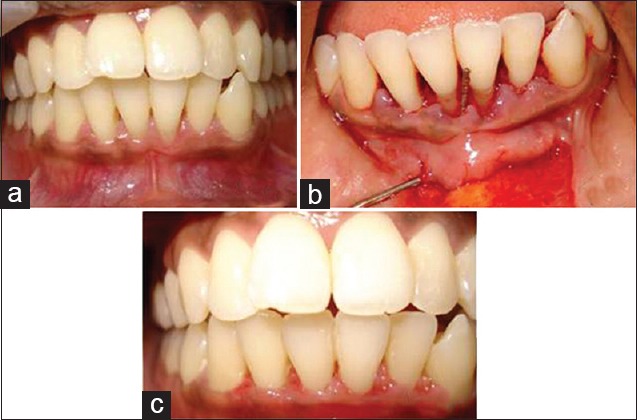

Figure 1.

(a) Preoperative view of control group; (b) operative view of control group; (c) 6 months postoperative view of control group

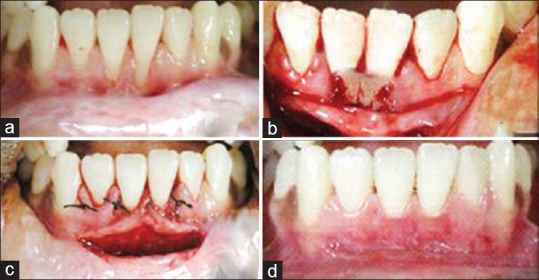

Figure 2.

(a) Preoperative view of test group; (b) platelet-rich fibrin placed in test group operative site; (c) sutures placed in test group operative site; (d) 6 months postoperative view of test group

Preparation of the platelet-rich fibrin

Ten milliliters of the patient's blood samples were taken in the operating room during the surgery. Immediately after the blood was drawn, the dried monovettes (without anticoagulant) were centrifuged at 2700 rpm for 12 min in a tabletop centrifuge (REMY® Laboratories).

The resultant product consists of the following three layers:

The topmost layer consisting of acellular platelet poor plasma

PRF clot in the middle

Red blood cells at the bottom.

Because of the absence of an anticoagulant, blood begins to coagulate as soon as it comes in contact with the glass surface. Therefore, for successful preparation of PRF, speedy blood collection, and immediate centrifugation, before the clotting cascade is initiated is absolutely essential.[14]

The PRF clots were recovered and packed tightly in two sterile gauze pieces and compressed in order to obtain the resistant fibrin membranes that could be placed on the gingival recession site and stabilized before flap closure with 4-0 absorbable surgical suture (16 mm braided coated polyglactin 910 undyed with 3/8 circle cutting needle).

Postoperative care

The patients of both groups were prescribed analgesics (ibuprofen 400 mg and paracetamol 500 mg combination for 3 days) to control postoperative discomfort. No antibiotics were prescribed. Postoperative instructions were given. The pateints were instructed to avoid pulling on their lips to observe the surgical site. Also, the they were instructed to avoid chewing in surgical area during first postoperative day. They were instructed to avoid hot and spicy food for 1-day after surgery. They were instructed to come back to repack the surgical site if a portion of the pack is lost from the operated area. They were instructed to rinse with 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate (periogard) immediately after the surgical procedure and twice daily, thereafter until normal plaque control technique can be resumed. Recall appointments were scheduled after 10 days and at 3 and 6 months.

Healing

The sutures were removed 10 days after the procedure. The surgical site was examined for uneventful healing. The patients were instructed to use a soft toothbrush for mechanical plaque control in the surgical area by a coronally directed roll technique. Oral hygiene instruction and professional cleaning were provided at each follow-up visit when indicated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using a statistical software package (Statistical Package for Social Science [SPSS] version 15, REMY laboratory instruments, Mumbai, India). The paired sample statistics was used to compare the difference in GRH, width, and the change in keratinized gingiva preoperatively and after 6 months.

The Wilcoxon signed rank test was then utilized to analyze the parameters pre- and post-surgically within each group. The Mann–Whitney test was used to analyze parameters between study and control groups. The primary outcome was set as a reduction in GRW, GRH, and RC % and the secondary outcome was set as an increase in KGW.

All the patients completed the study. Mean and standard deviation of all the parameters were estimated for the recession sites. Mean changes were compared against the null hypothesis. Student's paired t-test was employed to test the significance of the differences between the means at baseline and at the 6th month. In the present study, P < 0.05 was considered as indicating statistical significance. The parameters that were compared were PD, CAL, KGW, GRH, and GRW. All these parameters were compared both between and within the groups.

RESULTS

In this study, 20 sites from 10 patients in the control group were treated with bridge flap alone. Also, 20 sites from 10 patients in the test group were treated with bridge flap and PRF.

Baseline measurements

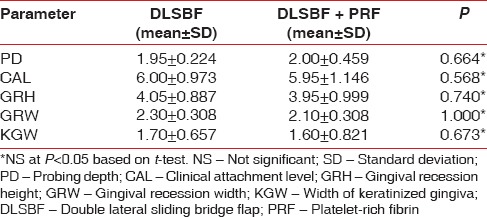

The baseline values of both the groups are given in Table 1. The mean preoperative recession height in the DLSBF group was 4.1 mm ± 0.9 mm and 4 mm ± 1 mm in PRF + bridge flap group. The mean preoperative recession width in the DLSBF group was 2.3 mm ± 0.5 mm and in the PRF + DLSBF group was 2.1 mm ± 0.3 mm. The mean preoperative width of attached gingiva in the DLSBF and PRF + DLSBF group were 1.70 mm ± 0.657 mm and 1.60 mm ± 0.821 mm, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline parameters

Intergroup comparisons

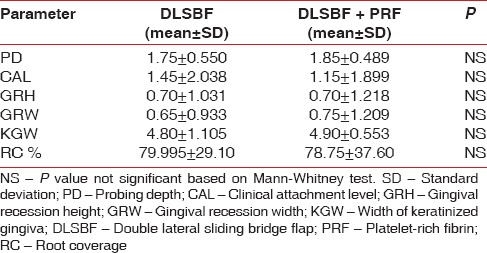

At 6 months, the mean RC for both the groups was 80% in DLSBF group and 78.75% in DLSBF + PRF [Table 2]. The comparison of RC between the two groups showed no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Intergroup comparisons at 24 weeks

Overall, 13 out of 20 sites showed 100% RC in DLSBF group. Fourteen out of 20 sites showed 100% RC in PRF + DLSBF group. Other parameters like RW, KGW, PD, and CAL also showed no significant difference between groups.

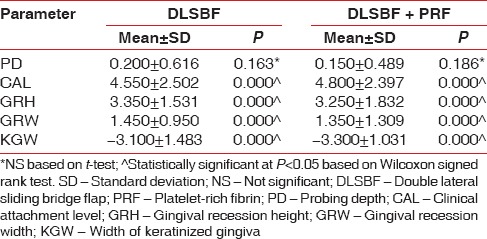

Intragroup comparisons

There was a significant reduction (P < 0.05) in the height of gingival recession and width of gingival recession from baseline to 6 months in both the groups [Table 3]. The increase in width of attached gingiva was also significant in both the groups (P < 0.05). The gain of CAL and RC was also significant in both the groups (P < 0.05). The measurements of PD remained consistent throughout the study.

Table 3.

Intragroup comparisons at 24 weeks

DISCUSSION

Root hypersensitivity, predisposition to root caries and patient's intense esthetic concern has broadened the scope of RC therapy. Several procedures have been proposed to cover gingival recessions.

In the original Edlan and Mejchar technique, which was developed to deepen the vestibule and not to cover gingival recessions, there was alveolar bone exposure. But in this modification there is no alveolar bone exposure. This could explain the uncomplicated and rapid healing in most cases. Also, in this technique, a CRF could be used for RC even in the presence of an attached gingiva width of <3 mm done by Marggraf.[10,11]

The other advantages of this technique are that by releasing the periosteal fibers, the frenal pull also can be relieved. There is no necessity for a separate frenectomy procedure.

Currently, PRF has been successfully tested in a number of procedures including maxillofacial surgery, periodontal surgery, and implantology by Sharma and Pradeep[16] PRF has many advantages over platelet-rich plasma (PRP). It eliminates the redundant process of adding anticoagulant as well as the need to neutralize it. The addition of bovine-derived thrombin to promote conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin in PRP is also eliminated. The elimination of these steps considerably reduces biochemical handling of blood as well as risks associated with the use of bovine-derived thrombin. The conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin takes place slowly with small quantities of physiologically available thrombin present in the blood sample itself. Thus, a physiologic architecture that is very favorable to the healing process is obtained due to this slow polymerization process.[14]

Sánchez et al.[17] have elaborated on the potential risks associated with the use of PRP. The preparation of PRP involves the isolation of PRP after that gel formation is accelerated using calcium chloride and bovine thrombin. It has been discovered that the use of bovine thrombin may be associated with the development of antibodies to the factors V, XI, and thrombin resulting in the risk of life-threatening coagulopathies. Bovine thrombin preparations have been shown to contain factor V, which could result in the stimulation of the immune system when challenged with a foreign protein. Other methods for safer preparation of PRP include the utilization of recombinant human thrombin, autologous thrombin or perhaps extra-purified thrombin.[18]

In both the groups, complete RC as defined by Miller in 1987 was achieved in 80% of cases.[19] Miller defined complete RC in clinical terms as location of soft tissue margin at the CEJ, presence of clinical attachment to the root, a sulcus depth of 2 mm or less and absence of bleeding on probing.

The results of our study show that bridge flap technique can be used to cover multiple recessions as seen in both the study and control groups. Even in the presence of a narrow width of attached gingiva, a high level of RC was achieved in both the groups. This was in accordance with the studies done by Marggraf[10] and Romanos et al.[20]

In both the study and control groups, there was a significant increase in the width of attached gingiva. Scientific data obtained from well-controlled clinical and experimental studies have unequivocally demonstrated that the apico-coronal width of the gingiva and the presence of an attached portion of gingiva are not of decisive importance for the maintenance of gingival health and height of the periodontal tissues as concluded by Freedman et al.[21] Consequently, the presence of a narrow zone of gingiva per se cannot justify surgical intervention. Although increasing the band of attached gingiva is not the main aim of the study, this was also achieved as a secondary outcome in the due course of the treatment in both the groups. The gain of keratinized gingiva obtained in this study was similar to the results of the study done by Mooney and Silva[22] in which RC was attempted with CRF alone and another study by Huang et al.[23] in which RC was attempted with CRF-PRP.

The results from the study group of our study are in accordance with the studies by Wiltfang et al.[18] and Corso et al.[24] who have confirmed the successful use of PRF membranes in the management of both single and multiple gingival recession defects.

In a similar study Eren and Atilla,[25] accepted that the PRF method is practical and simple to perform. Additionally, they found PRF to be superior to subepithelial connective tissue graft since it eliminates the requirement of a donor site. Conversely, Aroca et al.[26] found inferior RC upon the addition of an autologous PRF clot to a modified coronally advanced flap (MCAF) (study group) when compared with MCAF alone (control group) for the treatment of multiple gingival recessions.

In our study, in both the study and control groups, neither the quantity of gingival recession, nor the quality of the supporting tissues affected the success of this technique. This observation is supported by two human studies that showed that the absence of a narrow band of keratinized gingiva did not interfere with gingivectomy/flap surgery results. In both the groups, the DLSBF technique resulted in the development of keratinized epithelium of the transposed alveolar mucosa. The possible sources of induction of keratinization of the underlying tissues according to the study done by Bokan[27] would be the remnants of the attached gingiva left on the flap margin after the paramarginal incision, the retained de-epithelialized gingival tissue and the periodontal ligament. Also, some of the technical aspects described during the bridge flap procedure were key to its success. The initial semilunar incision was at least 2 GR + 2 mm apical to the gingival recession and this provided a wide flap Romanos et al.[20] Furthermore, with the bridge flap technique, the incidence of the recurrent recession is reduced considerably by the simultaneous extension of the vestibule, as the mucosal flap cannot be influenced by tension from an apical direction.

No statistically significant differences were noted between the study and control groups, with respect to all the clinical parameters suggesting that both procedures are comparable to treat Miller's Class I and II recession defects. The application of PRF showed no additional benefit to enhance outcomes achieved by DLSBF alone. This may be partly due to the favorable results obtained in groups, small sample size and defects (Miller's Class I and II) known to experience predictable RC. The results are comparable to the meta-analysis done by Fabbro et al.,[28] who concluded that there was no significant benefit of platelet concentrates for the treatment of gingival recession.

The lack of benefit of PRF in the test site of the present study does not rule out the interest of PRF in mucogingival surgery for denuded root surfaces. Surgical variables that may affect the final result are PRF consistency, relationship with a CEJ positioning, and platelet concentration as said by Marx et al.[29]

CONCLUSION

This study indicates that bridge flap is a predictable approach to treat Miller's Class I and II gingival recession. The additional application of PRF failed to improve RC after DLSBF in Miller's Class I and II defects. Therefore, future clinical and histologic studies with larger sample sizes, longer follow-up periods, and more challenging recession defects are recommended to further explore this hypothesis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carranza FA, Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR. Periodontal plastic and esthetic surgery. In: Carranza FA, editor. Clinical Periodontology. 10th ed. Missouri: Saunders Publishers; 2006. pp. 1005–29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maynard JG, Jr, Wilson RD. Physiologic dimensions of the periodontium significant to the restorative dentist. J Periodontol. 1979;50:170–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1979.50.4.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowers GM. A study of the width of attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1963;34:201–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ainamo J, Löe H. Anatomical characteristics of gingiva. A clinical and microscopic study of the free and attached gingiva. J Periodontol. 1966;37:5–13. doi: 10.1902/jop.1966.37.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang NP, Löe H. The relationship between the width of keratinized gingiva and gingival health. J Periodontol. 1972;43:623–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1972.43.10.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grupe H, Warren R. Repair of gingival defects by a sliding flap operation. J Periodontol. 1956;27:92–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindhe J, Nyman S. Alterations of the position of the marginal soft tissue following periodontal surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:525–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1980.tb02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith RG. Gingival recession. Reappraisal of an enigmatic condition and a new index for monitoring. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:201–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortellini P, Pini Prato GP, DeSanctis M, Baldi C, Clauser C. Guided tissue regeneration procedure in the treatment of a bone dehiscence associated with a gingival recession: A case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1991;11:460–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marggraf E. A direct technique with a double lateral bridging flap for coverage of denuded root surface and gingiva extension. Clinical evaluation after 2 years. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edlan A, Mejchar B. Plastic surgery of the vestibule in periodontal therapy. Int Dent J. 1963;13:593–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choukroun J, Adda F, Schoeffler C, Vervelle A. Opportunity in perio-implant: The PRF. Implantology. 2001;42:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lekovic V, Camargo PM, Weinlaender M, Vasilic N, Aleksic Z, Kenney EB. Effectiveness of a combination of platelet-rich plasma, bovine porous bone mineral and guided tissue regeneration in the treatment of mandibular grade II molar furcations in humans. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:746–51. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: Technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jankovic S, Aleksic Z, Klokkevold P, Lekovic V, Dimitrijevic B, Kenney EB, et al. Use of platelet-rich fibrin membrane following treatment of gingival recession: A randomized clinical trial. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2012;32:e41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma A, Pradeep AR. Autologous platelet-rich fibrin in the treatment of mandibular degree II furcation defects: A randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1396–403. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.100731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez AR, Sheridan PJ, Kupp LI. Is platelet-rich plasma the perfect enhancement factor?. A current review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003;18:93–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiltfang JP, Terheyden H, Gassling V. Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) vs. Platelet Rich Fibrin (PRF): Comparison of Growth Factor Content and Osteoblast Proliferation and Differentiation in the Cell Culture. Report of the 2nd International Symposium on Growth Factors (SyFac 2005) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller PD., Jr Root coverage with the free gingival graft. Factors associated with incomplete coverage. J Periodontol. 1987;58:674–81. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.10.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romanos GE, Bernimoulin JP, Marggraf E. The double lateral bridging flap for coverage of denuded root surface: Longitudinal study and clinical evaluation after 5 to 8 years. J Periodontol. 1993;64:683–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.8.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman AL, Salkin LM, Stein MD, Green K. A 10-year longitudinal study of untreated mucogingival defects. J Periodontol. 1992;63:71–2. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.2.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mooney DJ, Silva EA. Tissue engineering: A glue for biomaterials. Nat Mater. 2007;6:327–8. doi: 10.1038/nmat1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang LH, Neiva RE, Soehren SE, Giannobile WV, Wang HL. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on the coronally advanced flap root coverage procedure: A pilot human trial. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1768–77. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.10.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Corso M, Sammartino G, Dohan Ehrenfest DM. Re: Clinical evaluation of a modified coronally advanced flap alone or in combination with a platelet-rich fibrin membrane for the treatment of adjacent multiple gingival recessions: A 6-month study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1694–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eren G, Atilla G. Platelet-rich fibrin in the treatment of bilateral gingival recessions. J Periodontol. 2012;2:154–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aroca S, Keglevich T, Barbieri B, Gera I, Etienne D. Clinical evaluation of a modified coronally advanced flap alone or in combination with a platelet-rich fibrin membrane for the treatment of adjacent multiple gingival recessions: A 6-month study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:244–52. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bokan I. Potential of gingival connective tissue to induce keratinization of an alveolar mucosal flap: A long-term histologic and clinical assessment. Case report. Quintessence Int. 1997;28:731–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Del Fabbro M, Bortolin M, Taschieri S, Weinstein R. Is platelet concentrate advantageous for the surgical treatment of periodontal diseases?. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1100–11. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marx RE, Carlson ER, Eichstaedt RM, Schimmele SR, Strauss JE, Georgeff KR. Platelet-rich plasma: Growth factor enhancement for bone grafts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:638–46. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]