Abstract

Packaging clinically relevant hydrophobic drugs into a self-assembled nanoparticle can improve their aqueous solubility, plasma half-life, tumor specific uptake and therapeutic potential. To this end, here we conjugated paclitaxel (PTX) to recombinant chimeric polypeptides (CPs) that spontaneously self-assemble into ~60-nm diameter near-monodisperse nanoparticles that increased the systemic exposure of PTX by 7-fold compared to free drug and 2-fold compared to the FDA approved taxane nanoformulation (Abraxane®). The tumor uptake of the CP-PTX nanoparticle was 5-fold greater than free drug and 2-fold greater than Abraxane. In a murine cancer model of human triple negative breast cancer and prostate cancer, CP-PTX induced near complete tumor regression after a single dose in both tumor models, whereas at the same dose, no mice treated with Abraxane survived for more than 80 days (breast) and 60 days (prostate) respectively. These results show that a molecularly engineered nanoparticle with precisely engineered design features outperforms Abraxane, the current gold standard for paclitaxel delivery.

Keywords: Chimeric polypeptide, paclitaxel, nanoparticle, drug delivery, triple negative breast cancer, prostate cancer, Abraxane

Introduction

Most cancer chemotherapeutics are hydrophobic small molecules; this is true of many of the cytotoxic agents that have been in clinical use for many decades1, as well as the next generation of “targeted” therapeutics—currently entering the clinic—that are small molecule drugs specific for molecular targets that are dysregulated in cancers2. The small size and poor solubility of many of these cancer drugs leads to fast renal clearance and poor bioavailability by the typical—oral or parenteral—routes of delivery, and leads to limited accumulation in tumors, and hence poor clinical outcomes. Unlocking the full therapeutic potential of hydrophobic small molecule cancer drugs requires new and innovative drug formulation strategies that can be applied across a class of structurally diverse hydrophobic drugs to solve the recurring problem of poor solubility, sub-optimal pharmacokinetics (PK), and low bioavailability. An emerging approach is to package highly hydrophobic drugs into highly water soluble nanoscale delivery vehicles (10–100 nm diameter), as objects within this size range accumulate within solid tumors due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, which results from an aberrant and leaky tumor vasculature and the lack of poorly developed lymphatic drainage system in many solid tumors3, 4.

To this end, we have previously shown that conjugation of small molecules with an octanol-water distribution coefficient (logD) of > 1.5 drives the self-assembly of the CP into near-monodisperse sub-100 nm diameter nanoparticles5, and that Doxorubicin-loaded CP nanoparticles showed good efficacy in a subcutaneous (s.c.) murine colon cancer tumor model6. Those results, while promising, only suggested the clinical potential of this nanotechnology, as they were limited to a single, murine tumor in a subcutaneous (s.c.) model, the therapeutic index of this formulation was modest, and the CP-Doxorubicin nanoparticles were not compared to any clinically approved nanoscale formulations of the drug.

This paper goes well beyond the preliminary in vivo efficacy results previously reported for CP-doxorubicin nanoparticles and assesses, through extensive in vivo experiments, the clinical potential of this nanotechnology. Clinical translation of any new nanoscale drug delivery platform requires that it be useful with more than one drug, and that it demonstrate efficacy in multiple tumors implanted at multiple—s.c. and preferably orthotopic—anatomical sites. We report herein the synthesis and in vivo delivery of near-monodisperse, sub-100-nm-sized nanoparticles that are composed of paclitaxel (PTX) conjugated to a recombinant chimeric polypeptide (CP) that self-assembles into spherical nanoparticles upon drug attachment. The CP-PTX nanoparticles show potent tumor cell cytotoxicity, good pharmacokinetics and tumor accumulation, and low systemic toxicity. Notably, in a murine orthotopic tumor model of a human triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) that is highly refractory to chemotherapy, a single intravenous infusion of CP-PTX nanoparticles showed significantly better tumor regression than Abraxane at the same dose of drug. The therapeutic efficacy of the CP-PTX nanoparticles compared to Abraxane was even more pronounced in a s.c. prostate cancer model, as tumor bearing mice bearing prostate cancer tumors treated with Abraxane only survived ≤60 days, while 100% of the CP-PTX nanoparticle treated mice survived for more than 70 days. These results show that a molecularly engineered nanoparticle with precisely engineered design features can outperform Abraxane—the current gold standard for paclitaxel delivery—across multiple tumor models, which augurs well for its clinical translation.

Results

Choice of Drug

We chose paclitaxel (PTX) as the drug for several reasons. First, PTX is one of the most effective cytotoxic drugs to treat diverse solid tumors7, but it also provides a stringent test for any delivery system. This is because, with a logD of ~4.958, it is essentially insoluble in water. The second reason is that it allowed us to carry out a head-to-head comparison of our nanoparticle delivery system against Abraxane—a nanoparticle formulation of PTX bound to human serum albumin (HSA)—that is one of the few nanomedicines that have been approved by the FDA for cancer therapy9, 10. Such direct comparisons of new delivery systems against the clinical gold standard formulation are urgently needed, but are rarely reported in the literature, which casts significant doubt on the clinical utility of many of the new “nanomedicines” that are in the preclinical pipeline.

Synthesis of CP-PTX conjugate

The CP consists of two chemically distinct segments: an elastin-like polypeptide (ELP), which is a disordered, and highly water soluble recombinant peptide polymer11, fused to a short peptide segment containing eight cysteine residues that provide reactive sites for chemical conjugation of a chemotherapeutic of interest. The amino acid sequence of the CP is shown in Figure 1a. The CP was over-expressed from a plasmid-borne synthetic gene in E. coli using shaker-flask culture and purified from the sonicated bacterial lysate by inverse transition cycling, a non-chromatographic protein purification method described previously12. Three rounds of inverse transition cycling provided a monodisperse product with a yield of >100 mg l−1 of purified protein. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) showed that the molecular weight of the CP is 62650 Da, (Figure 2a, and Table 1) and SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Figure 1a) and HPLC confirmed that the CP had >95% purity (Supplementary Figure 1b).

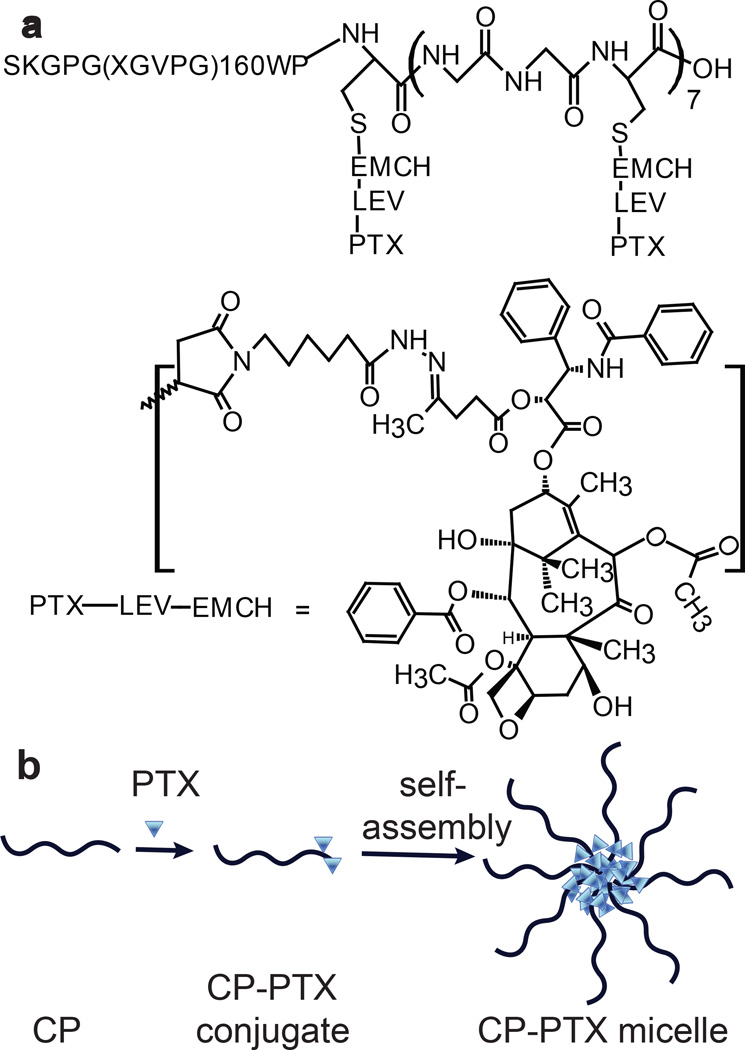

Figure 1. Structure of CP–PTX conjugate and schematic of the structure of CP-PTX nanoparticles.

a, The CP was synthesized by genetically encoded synthesis in E. coli, and conjugated to PTX at the multiple Cys residues at the C-terminal end of the CP by a pH sensitive linker. b, Attachment of the hydrophobic drug PTX triggers self-assembly of the CP into spherical nanoparticles with a drug-rich (blue triangles) core surrounded by a hydrophilic polypeptide corona (black chains).

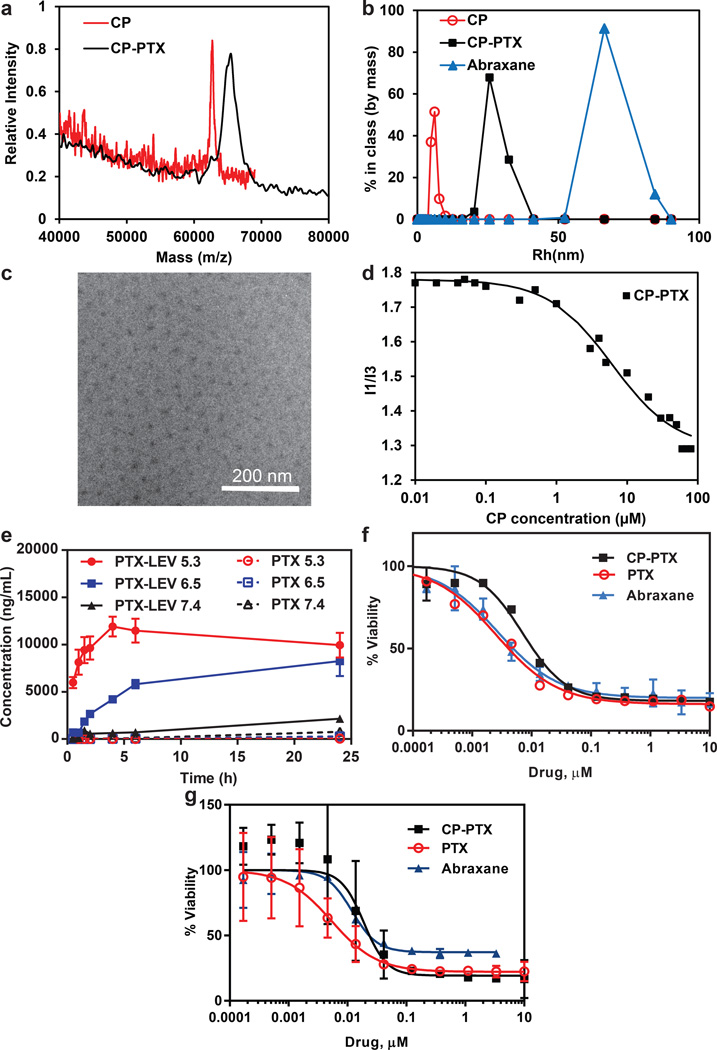

Figure 2. Characterization of CP–PTX nanoparticles.

a. MALDI-MASS of CP and CP-PTX conjugate. b-d, Determination of hydrodynamic radius (b), cryo-TEM (c), and critical aggregation concentration (d) of CP-PTX conjugate. e, The kinetics of pH-dependent release of PTX from CP–PTX nanoparticles as determined by LCMS/MS at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.3 (mean ± SD). f-g, Cell viability for CP–PTX and free PTX in MDA-MB-231 (f) and PC3 (g) cells (mean ± 95%CI).

To activate PTX for conjugation, it was first reacted with levulinic acid (LEV) at the 2’-OH position of PTX to introduce a keto-carbonyl functional group (Supplementary Figure 2). The product was reacted with n-ε-maleimidocaproic acid hydrazide tri-fluoroacetic acid to incorporate an internal, acid-labile hydrazone moiety with a terminal maleimide6 (Supplementary Figure 2), and this activated drug was covalently attached to the Cys residues of the CP (Figure 1 a , b). Purified CP-PTX has ~2 drug molecules per CP, as determined by MALDI-TOF MS (Figure 1a), as determined by the mass difference between the conjugate and the parent CP (Supplementary Table 1).

Characterization of CP-PTX conjugate

Upon conjugation of PTX, the CP-PTX conjugate spontaneously self-assembled into near-monodisperse spherical micelles (Figure 1a). As PTX has a logD of 4.95, these results are entirely consistent with our previous observation that molecules with a logD > 1.5 can trigger the self-assembly of a CP into nanoparticles6. To determine the molecular weight, radius of gyration (Rg), and hydrodynamic radius (Rh), the CP-PTX conjugate was analyzed by static and dynamic light scattering (SLS and DLS). DLS of the CP-PTX conjugate in PBS at 37 °C showed nanoparticles with a Rh of 32.5±0.6 nm (Figure 2b, Supplementary Figure 4b). Analysis of the partial Zimm plot obtained from SLS showed that the Rg of the CP-PTX nanoparticles was 26.6 nm and that the aggregation number of the nanoparticles was 50 (Supplementary Figure 4c, d and Supplementary Table 1). The experimentally determined form factor (ρ)—calculated as Rg/Rh—was 0.82, which is close to the theoretical value of 0.775 for spherical micelles13.

The size and spherical morphology of the CP-PTX nanoparticles were confirmed by cryo-TEM, which allows for the direct visualization of self-assembled structures in a near-native, hydrated state (Figure 2c, Supplementary Figure 4g). Only the hydrophobic core of CP-PTX nanoparticles is visualized by cryo-TEM, due to the low electron density and high degree of hydration of the ELP chains in the corona of the nanoparticles. The average nanoparticle radius determined by cryo-TEM (RTEM, deduced from the average core-to-core distance) was measured as 23±0.4 nm (n = 50), and the average core radius (Rcore) was measured as 7.5±0.2 nm. The slight discrepancy between RTEM and the slightly larger Rg and Rh obtained from light scattering could be due to a slight overlap of corona chains in the vitreous ice layer or due to nanoparticle compaction during the vitrification process.

We also measured the transition temperature (Tt) of the CP-PTX nanoparticles as a function of the CP concentration in PBS (Supplementary Figure 4e). The Tt of the CP-PTX nanoparticles is independent of the CP concentration in the range of 25–50 µM, which is in sharp contrast to CP unimers (no PTX attached) whose transition temperatures vary significantly with their composition and concentration (Supplementary Figure 4e). In PBS, the Tt of the CP-PTX nanoparticles was 45 °C at 25 µM whereas the Tt of the CP ranged from 65 °C for 50 µm to 69 °C for 25 µM. We also examined the thermal response of the CP-PTX nanoparticles in 90% FBS (a close approximation to physiological conditions). We found that the Tt of CP-PTX nanoparticles decreased by ~ 6 °C, consistent with previous results5 (Supplementary Figure 4f).

Abraxane was also analyzed by DLS, SLS, and cryo-TEM. Light scattering showed self-assembled structures with a Rg of 79 nm and a Rh of 96 nm (Supplementary Table 2), both of which are in agreement with the previously reported diameter of 130 nm determined by DLS14. The shape factor ρ = 0.83, is also close to the theoretical value of 0.775 for spherical micelles, and the aggregation number was 1757 albumin molecules per nanoparticle, implying a highly dense structure. This high density allowed Abraxane to be visualized with high contrast by cryo-TEM, which showed that Abraxane has a somewhat irregular but approximately spherical morphology (Supplementary Figure 5).

The thermodynamic stability of the CP-PTX micelles was measured by a pyrene fluorescence assay, which showed that the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of the CP-PTX nanoparticles was ~1 µM (Figure 2d). The CMC was confirmed by DLS as a function of CP-PTX concentration, which showed that the population with a Rh of ~32 nm persisted down to a concentration of 5 µM (Supplementary Figure 4a), with no evidence of a second population of CP-PTX unimers.

pH dependent drug release

The liberation of free drug from the CP-PTX nanoparticles requires the pH-dependent cleavage of the hydrazone and ester bond (Figure 1b). To evaluate the kinetics of drug release, CP-PTX nanoparticles were incubated in buffer solutions at three different pHs; pH 7.4 (neutral), 6.5 (tumor) or 5.3 (endosomal) and at 37 °C for 24 h (Figure 2e). The release of PTX-LEV and PTX was monitored by LCMS-MS. At pH 7.4, both the hydrazone and ester bond were stable, and no significant release of free drug was observed over 24 h compared to that at acidic pH. In contrast, at pH 6.5, PTX-LEV was generated with a faster rate because of cleavage of the ester bond, and reached a plateau at 24 h (Figure 2e). Most strikingly, at pH 5.3, the hydrazone bond was cleaved with a much faster rate and the release of PTX reached steady state within 8 h (Figure 2e). These data confirm that the covalent conjugate of PTX is stable at the pH of blood, but that the drug is cleaved at an appreciable rate at the tumor interstitial pH (6.5)15 and at the pH in late endosomes (pH 5.3)16. Hence, the pH-dependent release of PTX from the CP-PTX nanoparticle suggests slow release of the drug in the interstitial space of the tumor and a faster rate of release in the endo-lysosomal compartment following cellular uptake of CP-PTX nanoparticles.

In vitro anti-cancer efficacy

We chose MDA-MB-231, a human TNBC as the first cell line for treatment with the CP-PTX nanoparticle because PTX is used to treat patients with TNBC8. TNBC is characterized by a lack of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER-2 gene expression17, and 15–20 % of breast cancers are triple negative17. Unfortunately, TNBC presents a difficult clinical challenge as it is ultimately refractory to chemotherapy18, and displays a shorter median time to relapse and death than other sub-types of breast cancer18. Treatment of MDA-MB-231 with CP-PTX nanoparticles hence provides a stringent test of the clinical utility of this nanoparticle formulation. After 72 h exposure to CP-PTX nanoparticles, the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells was significantly inhibited (Figure 2f) and was comparable to the inhibition observed for treatment of cells with the same dose of Abraxane, and free drug in a -a DMSO solution diluted with PBS.

Next we evaluated the anti-cancer efficacy of CP-PTX in a human prostate cancer PC3 cell line. Like MDA-MB-231 cells, the proliferation of PC3 cells was also significantly inhibited (Figure 2g) with CP-PTX treatment and that was comparable to the same dose treatment of PTX. The IC50, defined as the concentration of PTX or PTX equivalent (for the CP-PTX nanoparticles and Abraxane) needed to kill 50% of cells, was found to be 7.1 nM and 18.9 nM for CP-PTX, 2.5 nM and 5.3 nM for PTX and 2.7 nM and 11.9 nM for Abraxane for MDA-MB-231 and PC cells respectively (Supplementary Table 3). The data clearly show that the CP-PTX nanoparticles inhibit the in vitro proliferation of both MDA-MB-231 and PC3 cells, and that conjugation of PTX to the CP does not markedly decrease the activity of the drug.

Stabilization of microtubule structure

To investigate the mechanism by which CP-PTX inhibits cell proliferation, we examined the ability of CP-PTX to stabilize microtubules and their dynamic assembly, given that PTX’s mode of action is disruption of microtubule dynamics19. To do so, we quantified the population of MDA-MB-231 cells in different stages of the cell cycle upon treatment with CP-PTX or PTX at a concentration of 1 nM PTX equivalent. We chose this concentration because most cells are alive at this concentration, as we wanted to avoid the complication introduced in the analysis if a sub-population of cells were to die during the experiment. The percentages of cell population in each phase of the cell cycle are indicated in the histograms (Figure 3a). Exposure of 1 nM CP-PTX showed significant G2/M arrest (31.3 %, p < 0.05 versus free drug) whereas cells treated with 1 nM of PTX had 25.1% (p < 0.05) of G2/M population (Figure 3a).

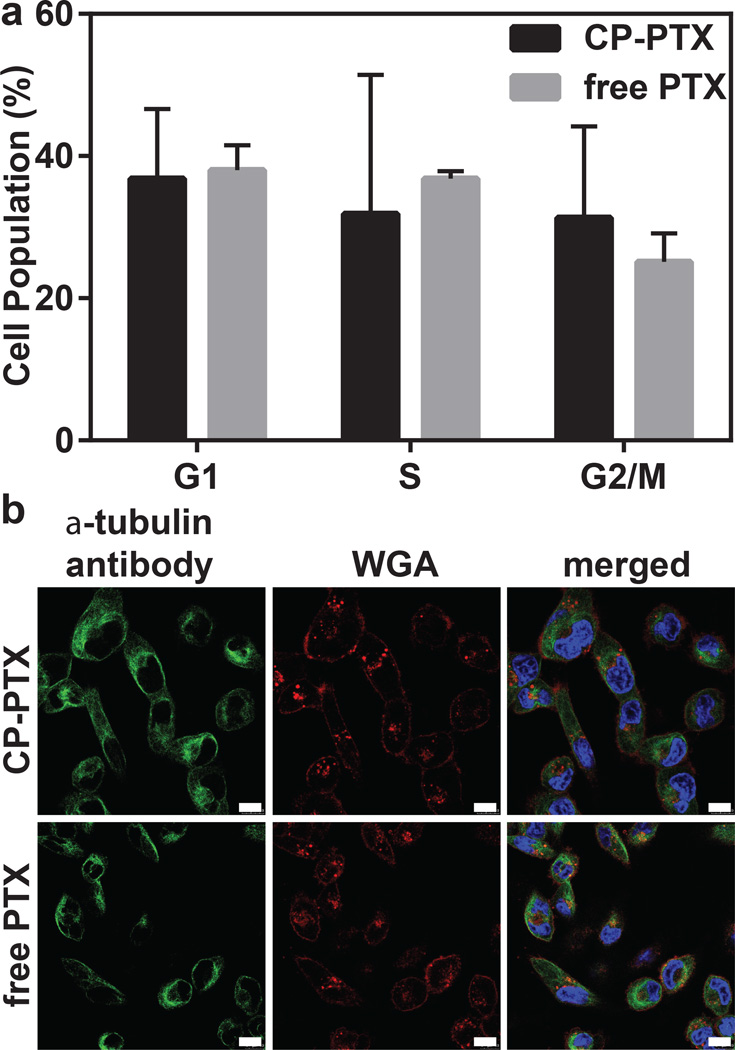

Figure 3. Cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase by CP-PTX.

a, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 1 nM PTX equivalent at 37 °C for 48 h. Adherent cells were collected, fixed in 70% ethanol, treated with RNase A and stained with propidium iodide (PI). Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are expressed as the percentage of each subpopulation as determined by analysis of 5,000 cells per sample. (Two way ANOVA, mean ± 95% CI, n=3, p< 0.05). b, Stabilization of microtubule structure by CP-PTX in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated with 1 nM CP-PTX or free PTX at 37 °C. After 24 h, cells were stained with α-tubulin antibody (green), Hoechst 33342 (blue) and WGA (red) and imaged by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar, 10 µm.

We next performed immunofluorescence studies to visualize the stabilization of microtubules by cells treated with CP-PTX. MDA-MB-231 cells were stained with an α-tubulin antibody 48 h after treatment with CP-PTX or free PTX to visualize microtubules, and cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342. After 48 h exposure of CP-PTX and PTX to MDA-MB-231 cells, the multipolar spindles were replaced by microtubule bundles and the nuclei were dumbbell-shaped in both CP-PTX and free PTX-treated cells (Figure 3b).

Determination of PK of CP-PTX conjugate

To evaluate and compare the plasma half-life, the CP-PTX nanoparticles, Abraxane and free drug were administered systemically and the plasma drug concentration was measured as a function of time post-injection (Figure 4a). The free drug was administered as the clinical parenteral formulation, consisting of PTX dissolved in a mixture of Cremophor® EL (polyoxyethylated castor oil) and ethanol (50:50, v/v), which is diluted right before injection20.

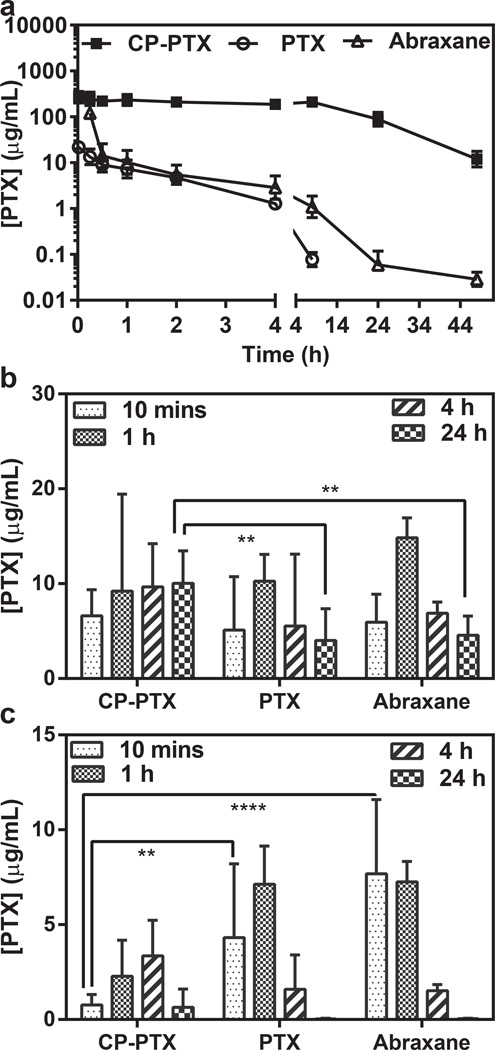

Figure 4. Plasma pharmacokinetics and tissue biodistribution.

a, Plasma PTX concentration as a function of time post-injection. A non-compartment model was fitted to the plasma PTX concentration, which yielded a terminal half-life of 8.4 h for CP–PTX and 3.8 h for Abraxane (mean ± 95% CI, n=4). b, c, The PTX concentration in tumor (b) and muscle (c) at 10 min and 24 h post-administration of free PTX, Abraxane and CP-PTX nanoparticles. ** and **** indicates p<0.01 and p<0.0001 respectively (Two way ANOVA, Tukey’s test) (mean ± 95% CI, n=4).

The measurement of PTX concentration and the various PTX degradation products for the CP-PTX nanoparticles is non-trivial because PTX is not fluorescent, and radioactively labeling PTX is both tedious and expensive. We employed LCMS-MS analysis to determine the in vivo concentration of PTX for free drug, Abraxane and the various CP-PTX products liberated from the nanoparticles by acid cleavage. The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using a non-compartment pharmacokinetic approach within WinNonlin software (Supplementary Information), yielding a terminal half-life for the CP-PTX nanoparticles of 8.4 ± 1.9 h and a plasma AUC of 5135 ± 447 µgmL−1h (Supplementary Table 4). In contrast, the terminal half-life for mice treated with the same dose of free PTX and Abraxane are only 1.2 ± 0.4 h (Supplementary Table 4) and 3.8 ±0.7 h (Figure 4a, Supplementary Table 4) and the AUC of free PTX and Abraxane are 27.0 ± 8.1 µgmL−1h and 80.8 ±45.1 µgmL−1h respectively. As PTX is linked to LEV through an ester bond, and the PTX-LEV conjugate is in turn conjugated with EMCH through a hydrazone bond in the CP-PTX conjugate, CP-PTX can potentially release PTX and PTX-LEV over time in systemic circulation. Hence, we also measured the AUC and terminal t1/2 for both PTX and the PTX-LEV conjugate. The AUCs for PTX and PTX-LEV in mice treated with the CP-PTX nanoparticles are 15.6 ± 2.2 µgmL−1h and 125.4 ± 16.0 µgmL−1h respectively, while the terminal t1/2 of PTX and PTX-LEV are 13.5 ± 10 h, and 10.7 ± 2.8 h respectively (Supplementary Table 4). These results clearly show that the CP-PTX nanoparticles provide a seven-fold higher plasma exposure than free drug and more than two-fold higher plasma exposure than Abraxane, which is a necessary pre-requisite for enhanced accumulation in solid tumors via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect4.

We next evaluated the in vivo bio-distribution of PTX delivered to tumors by systemically injected CP-PTX nanoparticles and Abraxane. Mice were administered free drug as the Cremophor™ formulation, Abraxane, or CP–PTX nanoparticles, and tissue samples of treated mice were collected after 10 min 1 h, 4 h, and 24 h (Figure 4b, c, Supplementary Figure 8, Supplementary Table 5). Notably, 24 h after administration, CP–PTX showed a 2.5-fold increase in drug concentration in the tumor, as compared with free drug at the same dose (Figure 4 b; two way ANOVA and Tukey’s test; p=0.01). Equally importantly, the CP–PTX nanoparticles significantly reduced the drug concentration at other sites in the body, including the muscle, liver, lung, kidney and heart (Supplementary Figure 8). In particular, the level of PTX delivered by CP-PTX nanoparticles in the muscle, liver, lung, kidney and heart was lower by 5.7, 7, 2.6, 5.5, and 5.4-fold respectively compared to free PTX (two way ANOVA and Tukey’s test; p= <0.001, <0.0001, <0.01, <0.0001, <0.01) and 9.9, 10.7, 27.3, 5.3, and 4.1 fold respectively compared to Abraxane (two way ANOVA and Tukey’s test; p= <0.0001, <0.0001, <0.01, <0.0001). Most importantly, following CP-PTX treatment, the concentration of PTX remains constant over time (Figure 4b) whereas for free drug and Abraxane treatment, the PTX concentration decreased with time (Figure 4b). The decreased accumulation in the muscle is notable, as neurotoxicity is the dose-limiting side effect of free PTX21. Furthermore, the accumulation of PTX in the liver is also significantly lower for CP-PTX nanoparticle treated mice compared to Abraxane and free PTX treatments. This is important because nanoparticles typically show significant accumulation in the liver22, 23.

To compare the therapeutic effect of CP–PTX nanoparticles versus free PTX, both formulations were administered in a dose escalation study to determine their maximum tolerated dose (MTD). The MTD of PTX was 25 mg kg−1 BW, and the MTD for CP–PTX was ≥50 mg PTX Equiv.kg−1 BW (Supplementary Figure 6). We believe that the true MTD of CP-PTX nanoparticles is greater than 50 mg.kg−1, but we were unable to increase the dose beyond 50 mg.kg−1 because of the viscosity of the solution. In any event, by administration of the CP–PTX nanoparticles at 50 mg.kg−1, it is potentially possible to increase the absolute concentration of drug in the tumor at 24 h by an estimated 5-fold over free drug while minimizing toxic side effects. The increase in tumor exposure and the decrease in exposure of the drug to muscle, liver, lung, kidney and heart is one mechanism that may explain why the MTD of CP–PTX nanoparticles is greater than that of free PTX (Figure 4 b, c, Supplementary Figure 8, Supplementary Table 5), and suggested that CP–PTX nanoparticle formulation may improve the therapeutic index of PTX.

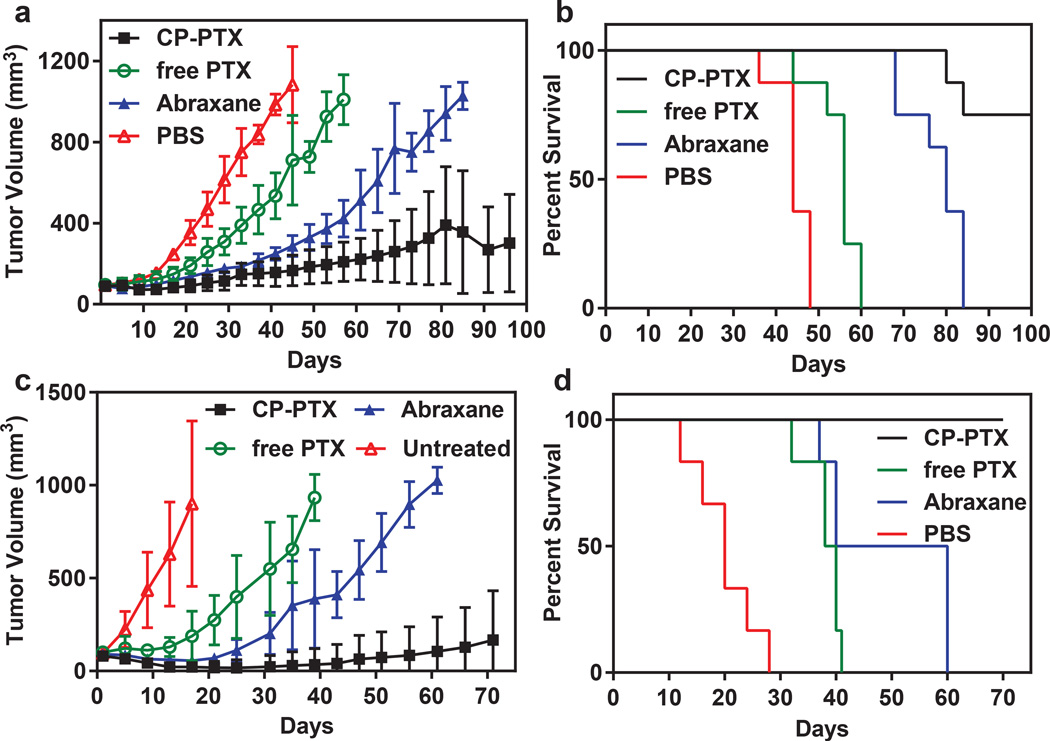

CP–PTX nanoparticles were first evaluated for their in vivo anti-tumor activity in a subcutaneous MDA-MB-231 xenograft model (Supplementary Figure 7) with a dose of 30 mg.kg−1 BW to compare with the anti-tumor efficacy of PTX at a similar dose. Significant tumor regression with improved survival was observed with mice treated with CP-PTX compared to PTX (Supplementary Figure 7). Next we evaluated the tumor regression efficacy of CP-PTX in an orthotopic MDA-MB-231 model. Mice with MDA-MB-231 tumors were treated once intravenously with PBS, PTX at its MTD (25 mg.kg−1), CP–PTX nanoparticles at 50 mg.kg−1 of PTX equivalent, and Abraxane, also at 50 mg.kg−1 of PTX equivalent (Figure 5a). Six weeks after treatment, CP–PTX treated mice had a mean tumor volume of 150 mm3 (n=8) versus 216 mm3 (n=8) for Abraxane, 535 mm3 (n=8) for free-drug- (Tukey; p=0.0001) and 985 mm3 (n=8) for PBS treated controls (Tukey; p=0.0001). Clearly, the CP–PTX formulation outperforms Abraxane and free drug in reducing tumor volume, which correlated with a substantial increase in animal survival (Figure 5b). This is notable as free PTX was ineffective in controlling tumor growth. The median survival time for mice treated with PBS (n = 8) was 44 days, and treatment with the Cremophor™ formulation of PTX (n= 8) slightly increased this survival to 56 days (Kaplan–Meier, Wilcoxon test, p<0.0001). Treatment with Abraxane further increased the survival to 80 days (Kaplan–Meier, Wilcoxon test, p<0.0001). In contrast, six out of eight mice were alive for up to 100 days after treatment of CP–PTX nanoparticles and two of eight mice had no residual tumors (Figure 5b). These results clearly demonstrate that treatment with CP-PTX significantly improved the survival of mice bearing orthotopic MDA-MB-231 tumor over free drug (Kaplan–Meier, Wilcoxon test, p<0.0001) and Abraxane (Kaplan–Meier, Wilcoxon test, p<0.0001)

Figure 5. Anti-tumor activity of CP–PTX nanoparticles.

a, and b, tumor cells (MDA-MB-231) were implanted in the mammary fat pad on day zero. When the tumor volume reached ~100 mm3, mice were treated at the MTD with PBS (n=8), free PTX (25 mg kg−1 BW, n=8) or CP–PTX (50 mg PTX equiv.kg−1 BW, n=8). a, Tumor volume up to day 100 (mean ± 95% CI, n= 8). p = 0.0001 for CP–PTX versus PTX and PBS (day 44) respectively (Tukey test). b, Cumulative survival of mice (Kaplan–Meier). c-d, Tumor cells (PC3) were implanted on the right flank on day zero. When the tumor volume reached 50-100 mm3, mice were treated at the MTD with PBS (n=6), free PTX (25 mg kg−1 BW, n=6) and CP–PTX (50 mg PTX equiv.kg−1BW, n=6). c, Tumor volume up to day 70 (mean= ±95%CI, n=6). p=0.0001 for CP–PTX versus PTX and PBS (day 30) respectively (Tukey’s test). d, Cumulative survival of mice (Kaplan–Meier).

To rule out any possibility that the ELP carrier could itself potentiate an anti-tumor effect, we intravenously injected ELP (1900 mg kg−1 ELP) or co-injected ELP (1900 mg kg−1 ELP) and PTX (25 mg.kg−1) in mice bearing orthotopic MDA-MB-231 tumors. The ELP treatment had no effect on tumor growth or animal survival, and was similar to tumor growth and survival of PBS treated mice. Furthermore, mice co-treated with ELP and PTX had virtually identical response as mice treated with PTX (Supplementary Figure 14). These results clearly confirm that the ELP has no direct cytotoxicity.

To investigate whether these results would translate across tumor types, we next selected PC-3, a human prostate tumor, as a second tumor target. PC-3 xenografts were implanted s.c. in male nude mice and were treated with a single dose of PTX (25 mg.kg−1), CP-PTX nanoparticles, or Abraxane (both at 50 mg.kg−1). Mice treated with CP–PTX nanoparticles had a mean tumor volume of 23 mm3 (n=6) versus 216 mm3 (n=6) for Abraxane (Tukey; p<0.01) and 549 mm3 (n=6) for free drug (Tukey; p<0.05) 30 days after treatment. Clearly, the CP–PTX formulation at the MTD vastly outperforms Abraxane and free drug in reducing tumor volume, which correlated with a substantial increase in animal survival (Figure 5b). This is notable as free PTX is totally ineffective in controlling tumor growth. The median survival time for mice treated with PBS (n = 8) was 20 days, and treatment with PTX (n= 8) slightly increased survival to 39 days (Kaplan–Meier, log rank test, p<0.0001). Treatment of Abraxane further increased survival to 50 days (Kaplan–Meier, log rank test, p<0.0001). In contrast, all six mice were alive for up to 70 days after treatment of CP–PTX nanoparticles (Figure 5b). Thus, with only a single dose injection, CP–PTX nanoparticles provide a substantial curative effect.

Gene Expression analysis of tumors treated with CP-PTX and PTX

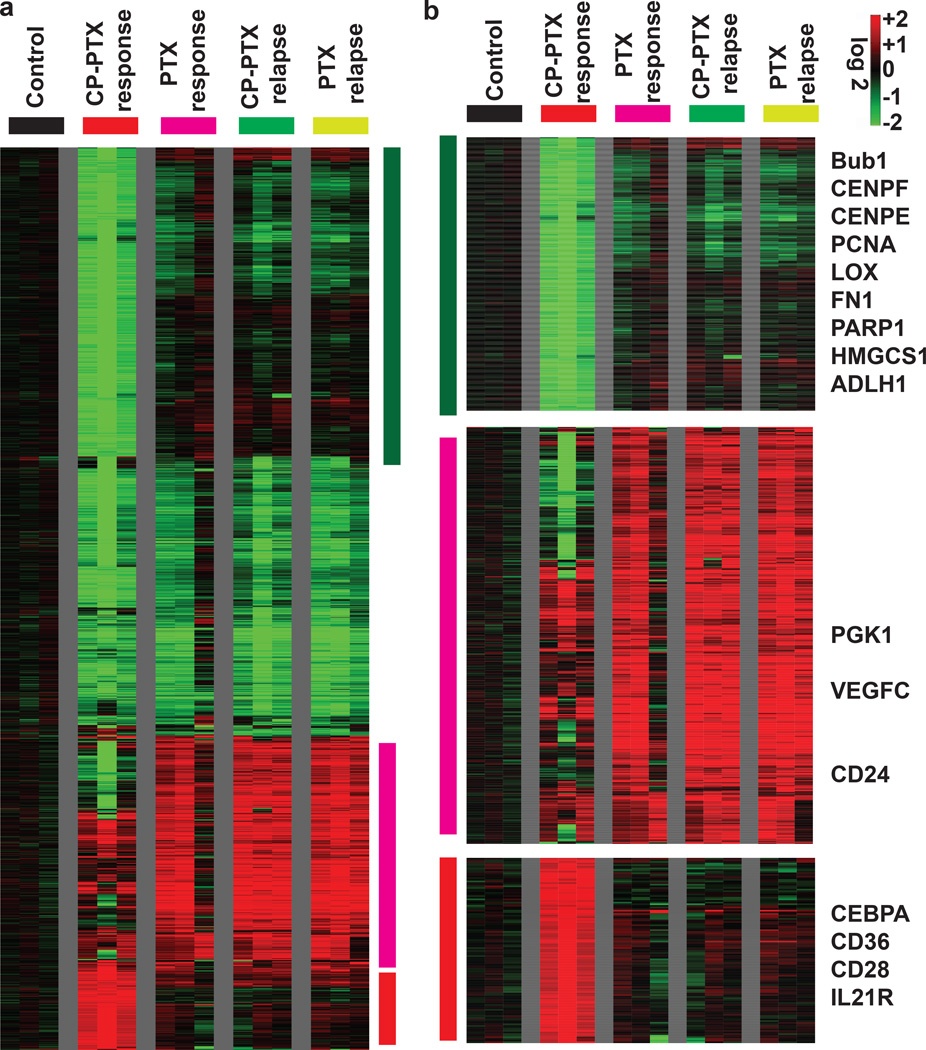

To explore the mechanism by which CP-PTX nanoparticles outperform the free drug, we next compared the genomic profiles for tumors obtained from mice treated with PBS, free PTX and CP-PTX. To determine the change in gene expression profile change over time, we also compared the genomic profiles of the response phase and relapse phase for both CP-PTX and free PTX treated tumors. Global gene expression analysis clearly showed that the gene expression profile of the CP-PTX response samples was distinct from all the other four remaining groups of samples (untreated control, PTX response, PTX relapse and CP-PTX relapse), and these differences were even larger than the differences between the controls vs. treated samples (Supplementary Data 1). To determine the effect of the empty vehicles on the gene expression of xenografts, global gene expression of ELP treated tumor was compared to that of PBS treatment. These experiments showed that ELP treatment had a minimal effect on the gene expression profile of xenografts (Supplementary Figure 14). To define the changes of each probe-set associated with each treatment, we performed a zero-transformation against the average expression levels of the same probe-sets of the control tumors, as described previously24, 25. At least two-fold change of 1,647 probe sets were found between groups and that were arranged by hierarchical clustering according to similarities in expression patterns (Figure 6a). This analysis highlights the distinct gene expression changes associated with the CP-PTX treated tumors with several clusters of genes that were only repressed or induced in the CP-PTX samples (Figure 6 a , b). For example, CP-PTX treated tumor showed significant repression of a large cluster of genes that are involved in DNA proliferation and repair, such as BubR1, centrosome components (CENPF, CENPE), PCNA and PARP1. In addition, several genes involved in fibrosis were also repressed in CP-PTX treated tumor including lysyl oxidase (LOX) and fibronectin (FN1). In contrast, a large cluster of genes were induced only in the PTX response, PTX relapse and CP-PTX relapse samples, but not in the CP-PTX response samples. This cluster contains the adhesion molecule CD24 and several genes that are known to be induced by hypoxia, including LOX, PGK1, BMIP3L and VEGFC.

Figure 6. Gene expression analysis of tumors treated with CP-PTX or PTX.

a, The global gene expression of xenografts that are responsive to treatment with CP-PTX nanoparticle or PTX or relapse upon treatment, was determined using microarray analysis using U133A2 (Affymetrix) arrays. The transcriptional response of each treatment was derived by zero-transformation. Selected gene clusters that were induced and repressed specifically in the CP-PTX tumors that responded to treatment are highlighted by the color bar. b, The three gene clusters that reflected the distinct changes in the CP-PTX response tumors were further expanded with selected names shown.

To identify the underlying biological processes that are affected by treatment with CP-PTX nanoparticles, we used Gene Set Enrichment Analysis26—a method to identify the enrichment or depletion biological processes as represented by gene sets—to perform pair-wise comparison between CP-PTX-response vs. untreated control, CP-PTX-relapse vs. untreated control as well as CP-PTX-response vs. CP-PTX-relapse. The most enriched and depleted pathways are presented in Supplementary Data 1. We found that the response to CP-PTX treatment, but not the CP-PTX-relapse samples, was associated with the depletion of TGF-β pathway (TGF-β pathway and SMAD2) and branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) catabolism (Supplementary Figure 15). The tumors’ response to CP-PTX nanoparticle treatment was also associated with the enrichment of genes in the classical adipogenic target of PPAR-γ, immune gene clusters and sensitivity to chemotherapies and γ-radiation. From the microarray data, we also studied some oncogenic pathways of the tumors treated with either CP-PTX or PTX. This data shows the upregulation of genes related to IFNγ, IFNα, and downregulation of E2F1, PI3K, EFGR, hypoxia, and genes involved in TGF-β signaling (Supplementary Figure 16).

Discussion

While taxanes are highly effective drugs for many cancers, the toxicity associated with solubilization strategies27, 28 the side effects that arise from non-specific drug accumulation in healthy organs provide the motivation to develop better delivery technologies. A liposomal formulation of PTX improved solubility of the drug and showed similar in vitro cytotoxicity against a variety of tumor cell lines compared to the Cremophor® formulaiton (Taxol®)29 but in vivo results of this formulation in a solid tumor were however, not reported.

In an alternative approach, taxanes have been physically encapsulated in synthetic polymer micelles (e.g., Genexol30 and NK10531). However, in most cases, physically encapsulated taxanes are rapidly released from polymeric micelles and bind with serum proteins, so that the improvement in plasma half-life over the Cremophor formulation only leads to a modest improvement in efficacy over free drug30, 32, 33. Abraxane— a ~130-nm diameter particle of PTX physically bound to human serum albumin (HSA)—is the most promising, and the only clinically approved nanoparticle carrier of PTX at this time, as it shows greater efficacy in preclinical models than the Cremophor formulation of PTX and lower systemic toxicity in human patients 23, 34–38.

An alternative approach to physical encapsulation is the covalent conjugation of the drug to a synthetic polymer. XYOTAX, a polyglutamic acid-paclitaxel conjugate showed promising preclinical results, but the typical taxane side effects of hypersensitivity, neuropathy, and neutropenia have been observed in Phase Ia and Ib clinical trials39. Another issue with XYOTAX is that the polyglutamate chain is hydrolytically labile, leading to rapid production of small polymer fragments of PTX during systemic circulation and non-specific biodistribution with high uptake in the kidneys, heart, and RES—liver and spleen—organs36. The plasma elimination half-life of Abraxane, and XYOTAX (polymeric conjugate) have been measured as 6.2 h (Abraxane), and 5.3 h (XYOTAX) respectively33, 22, 40. In our hand, Abraxane, despite being a nanoparticle formulation, had an elimination half-life only of 3.8 ± 0.7 h, which is similar to other polymeric formulations of paclitaxel. The lower plasma half-life of PTX in mice treated with Abraxane as compared to the 9.5 h long half-life of HSA in mice41, suggests that the drug does not remain associated with the protein long enough to fully leverage the favorable pharmacokinetics of HSA. This is consistent with a report that Abraxane does not exhibit tumor selective distribution of PTX that might be expected from a long circulating drug that can take advantage of the EPR effect, as it exhibits significant and promiscuous deposition in the prostate, liver, seminal vesicles, lung, pancreas, spleen, GI tract and kidney in a rat model22. In contrast, the accumulation of CP-PTX —and PTX released from CP-PTX nanoparticles— is significantly lower (2.6–27 fold) in the muscle, liver, heart, kidney and lung, compared to the Abraxane and free drug.

Global gene expression analysis of tumor tissue suggests that treatment with CP-PTX nanoparticles leads to the inhibition of genes like transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), E2F1, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and hypoxia, which are related to tumor cell proliferation, immune surveillance, survival and poor prognosis. Importantly, upregulation of interferon gamma (IFNγ) and interleukin 21 receptor (IL21R) related gene can potentially increases the cytolytic function of macrophages, NK cells, and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Significant repression of a large cluster of genes that are involved in DNA proliferation and repair, such as BubR1, centrosome components (CENPF, CENPE), PCNA and PARP1 were also observed in a global gene expression analysis of tumor tissue and are consistent with a recent report that mitotic arrest alone is not responsible for the in vivo efficacy of paclitaxel, but is related to chromosome missegregation on highly abnormal, multipolar spindles contributes to the in vivo efficacy of paclitaxel, in addition to mitotic arrest 42. Collectively, these results suggest that treatment with CP-PTX nanoparticles has a markedly different effect on gene expression within the tumor than treatment with free drug. These striking differences in the gene expression profiles, combined with similar observations for CP-Doxorubicin nanoparticles6, suggest that the effect of a nanoparticle drug is not identical to that of the free drug at the molecular level. Whether this is simply because of differences in the rate and amount of accumulation of the drug within different subcellular compartments of cells within tumors or whether it reflects a more fundamental redefinition of the pharmacology of the drug at the molecular level is an unanswered question, and one that we will pursue in future studies.

Beyond its efficacy, the CP-PTX nanoparticle formulation has several other useful attributes that augurs well for its translation to the clinic. First, synthetic polymeric micelles and polymer conjugates are more complicated to synthesize than the genetically encoded polypeptide described herein. Many synthetic polymeric vehicles are also not biodegradable, nor have they been shown to self-assemble across a broad range of hydrophobic molecules. In contrast, the CP nanoparticle system is a simple and rationally designed recombinant polypeptide that is extraordinarily efficient to synthesize and purify from E. coli, is biodegradable43, 44, and self-assembles into nearly monodisperse sub-100-nm nanoparticles in water upon conjugation of hydrophobic drugs, thereby obviating the need for complex processing of drug and carrier. Attachment of hydrophobic drugs solely at the chain end ensures that the drug is sequestered in the nanoparticle core, unlike other nanoparticle drug carriers, such as dendrimers3, metal nanoparticles45 or carbon nanotubes46 that expose the hydrophobic drugs at the nanoparticle-water interface. Like other polypeptide- and protein-drug conjugates47, the attachment of the drug through an acid-labile bond limits its premature release in systemic circulation and promotes release of the drug in regions of acidic pH, such as in the acidic extracellular space of solid tumors48 and within cells, thereby limiting spillover of the drug into circulation and healthy tissues. We believe that this combination of features make CP nanoparticles attractive for the delivery of the many hydrophobic chemotherapeutics that are clinically approved and other drug candidates that are abandoned along the clinical pipeline because of their unfavorable physicochemical properties and poor bioavailability.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of Chimeric Polypeptides

The ELP segment of the CP used for conjugation to paclitaxel (PTX) consists of the sequence SKGPG-(XGVPG)160-WPC(GGC)7 (single amino acid codes) where the guest residue X = V: G: A in a 1:7:8 ratio.

Expression and purification of CP

The ELP was expressed from a pET-24b expression plasmid in transformed into Eshcherichia coli strain BL21(DE3), using a previously published hyperexpression protocol, which relies on the leakiness of the T7 promoter49. 50 mL cultures grown for 16 h were used to inoculate six 1 L flasks of TB Dry supplemented with 45 µg/mL kanamycin. Each 1 L flask was then incubated at 37 °C and 210 rpm for 24 h, after which the cell suspension was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Each ELP was purified using inverse transition cycling (ITC), which has been described elsewhere12. Briefly, the cell pellet was resuspended in PBS and lysed via sonication on ice for 3 min (10 s on, 40 s off) (Masonix S-4000; Farmingdale, NY). Polyethyleneimine (PEI) 0.7% w/v was added to the lysate to precipitate nucleic acid contaminants. The supernatant was then subjected to multiple rounds of ITC as follows. The solution was heated to 37 °C in the presence of 3 M NaCl. The coacervate was centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 g and 20 °C, and resuspended in 20 mM TCEP in water, pH 7. This suspension was cooled to 4 °C, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 and 4 °C to remove any insoluble contaminants. Typically, 3 rounds of ITC generated a sufficiently pure product (>95% by SDS-PAGE).

Purity Analysis

Following CP purification, SDS-PAGE was performed on Biorad ReadyGels with a 4–20% Tris gradient. The gels were visualized by copper staining (0.5 M CuCl2). High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was also used to determine the purity of CP and CP-PTX conjugate, using a LC10 HPLC (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments; Columbia, MD). For HPLC analysis of the CP, a Shodex OHPak KB-804 column (New York, NY) and isocratic flow of 1.0 mL min−1of water: acetonitrile: formic acid [70:30:0.05] was used. For HPLC analysis of the CP-PTX conjugate, a Shodex OHPak SB-804 column (New York, NY) and isocratic flow of 0.5 mL min−1 of PBS: acetonitrile [70:30] was used. The HPLC data was quantified by the integrated area under the peak at an absorbance of 228 nm, corresponding to the absorbance of PTX.

Synthesis of CP-Paclitaxel Conjugate

Synthesis of paclitaxel-levulinic acid (PTX-LEV) conjugate

PTX-LEV was synthesized as described previously50. Briefly, levulinic acid (0.08 g, 0.7 mmol) and N,N’-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) (0.145 g, 0.7 mmol) was dissolved in dry Dimethylformamide (DMF) and mixed to each other, stirred for 30 mins at −20 °C. PTX (0.5 g, 0.58 mmol) and 4-Dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (0.5 g, 0.58 mmol) were dissolved in dry DMF and were added to the above mixture. The reaction mixture left stirred for 24 h at 4 °C. The reaction mixture was filtered and the DMF was evaporated to dryness. The compound was purified with column chromatography with silica gel and 1.5% methanol (MeOH) in chloroform as eluent. Retention Factor (Rf): 0.48 in EtOAc/Hexane=2:1.

Synthesis of activated paclitaxel (PTX-LEV-EMCH) and conjugation of paclitaxel with CP

PTX-LEV (0.05 g, 0.05 mmol) and N-ε-Maleimidocaproic acid hydrazide (EMCH) (0.018 g, 0.07 mmol) was dissolved in dry MeOH and left stirring in the dark for 36 h at 45 °C. After that, the MeOH was evaporated to dryness and the compound was purified with silica gel column chromatography with 2-2.5 % MeOH in chloroform as eluent. PTX-LEV-EMCH was immediately used for next step. Rf: 0.6 in 10 % MeOH in CHCl3. ESI-MS: 1159 [M+H]. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.24 (s, 1H, 12′), 9.28 (d, 1H, -HNBz), 7.97/7.7/7.67 (5H, aromatic: O–Bz), 7.82/7.48 (5H, aromatic: N–Bz), 7.44/7.17 (5H, aromatic: Ph3′-), 6.99 (s, 2H, 12′), 6.27 (s, 3H, 10-OCOCH3), 5.97 (m, 1H, 13), 5.4 (d, 1H, 2), 5.25 (dd, 1H, 3′), 4.91 (m, 1H, 5), 4.61 (d, 2H, 2′), 4.09 (m, 1H, 7), 3.99 (dd, 2H, 4-CCH2O), 3.57 (m, 1H, 3), 3.37 (m, 2H, 5′), 3.33(s, 3H, 10-OCOCH3), 3.17 (t, 2H, 4′), 3.16 (t, 3H, 11′), 2.6 (m, 2H, 6), 2.35 (m, 2H, 7′), 2.25 (s, 3H, 6′), 2.1 (s, 3H, 4-OCOCH3), 1.82 (s, 3H, 8-CH3), 1.75 (d, 2H, 14), 1.48 (s, 3H, 12-CH3), 1.49 (m, 2H 8′), 1.23 (m, 2H, 10′), 0.992/ 1.01 (s, 3H, 15-2CH3s), 0.84 (m, 2H, 9′). 13C NMR: (125 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 207.8, 202.35, 190.22, 174.52, 171.78, 171.05, 169.59, 166.279, 165.19, 155.51, 139.41, 134.43, 131.51, 129.92, 129.55, 128.64, 128.25, 127.56, 127.42, 127.23, 83.55, 80.18, 76.61, 75.20, 74.69, 70.67, 70.36, 65.31, 57.35, 54.47, 46.02, 42.87, 36.48, 34.40, 33.49, 32.97, 31.97, 29.75, 27.79, 26.30, 25.84, 24.65, 22.38, 21.36, 20.64, 16.76, 13.92, 9.72. HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C62H71N4O18 ([M + H]+): 1159.476341, found: 1159.47380.

Prior to conjugation with activated PTX, purified CP was suspended in reaction buffer (0.1 M NaPO4, 1 mM Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), pH 7.0) and reduced with 1 mL of Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) at neutral pH (100 mM, pH 7.0) at ~5x excess to thiol. Excess TCEP was removed from the solution by initiating the phase transition with sodium chloride (2.5 M) and centrifugation at 4,000 rpm at 25 °C for 10 minutes. The CP pellet obtained by centrifugation was re-suspended in ~2 mL of reaction buffer. Purified PTX-LEV-EMCH was re-suspended in ~2 mL of DMF and slowly transferred to the stirring CP solution. 1 mL of pH neutral TCEP (100 mM) was added and the reactants were stirred for 16 hrs at 20 °C in the dark. After reaction, the unreacted PTX-LEV-EMCH precipitate was separated by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm at 10 °C for 10 minutes. The supernatant was further purified by diluting it in 20% acetonitrile in PBS and centrifuging the solution in an Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units (MWCO: 10KDa, Millipore) at 2,500 rpm at 10 °C. The CP-PTX solution was washed twice with NH4HCO3 solution (pH 7.4) and then freeze dried.

Determination of Paclitaxel Conjugation Ratio

The conjugation ratio of PTX to CP was determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) of the CP-Paclitaxel conjugates and free CP using a Voyager DE-Pro MALDI-MS (Applied Biosystems) instrument equipped with a nitrogen laser (337 nm). The MALDI-TOF-MS samples were prepared in an aqueous 50% acetonitrile solution containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), using a sinapinic acid matrix. The conjugation ratio was determined by examining the increase in mass of the conjugate relative to free CP.

Dynamic Light Scattering

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was performed to determine the hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of the CP and CP-PTX nanoparticle in the range of 5- 25 µM CP concentration in presence of 30 mM TCEP and 25 °C using a DynaproTM plate reader (Wyatt Technology; Santa Barbara, CA), following filtration through 0.22 µm Millex-GV filters (Millipore; Billerica, MA). The data was analyzed with a regularization fit of the autocorrelation function and percent intensity was converted to mass intensity using Raleigh spheres model. To obtain histograms, regularization fits were used to determine the hydrodynamic radius as weighted by the percent by mass for a random coil.

Static and dynamic light scattering measurements were also performed on an ALV/CGS-3 goniometer system (Langen, Germany). Samples for the ALV/CGS-3 goniometer system were prepared in PBS and filtered through 0.22 µm Millex-GV filters into a 10 mm disposable borosilicate glass tube (Fisher). Simultaneous SLS and DLS measurements were obtained at 22°C for angles between 30°-150° at 5° increments, with measurements at each angle consisting of 3 runs for 15 seconds. The differential refractive index (dn/dc) was determined by measuring the refractive index at five different concentrations using an Abbemat 500 refractometer (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria). DLS data were analyzed by fitting the autocorrelation function to a biexponential decay using the HDRC software package (Germany). Hydrodynamic radius was plotted against angle and extraploted to zero. SLS data were analyzed by partial Zimm plots using ALV/Dynamic and Static FIT and PLOT software in order to determine the radius of gyration and molecular weight.

Temperature Programmed Turbidimetry

The transition temperature (Tt) of each sample was calculated by recording the optical density at 350 nm as a function of temperature (1 °C/min ramp) on a temperature controlled UV–vis spectrophotometer (Cary 300 Bio; Varian Instruments, Palo Alto, CA). The Tt was defined as the inflection point of the turbidity profile. All samples were analyzed in PBS with CP concentrations of 25 µM and 50 µM.

Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy

Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) was performed at Duke University’s Shared Materials Instrumentation Facility (Durham, NC). Lacey holey carbon grids (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) were glow discharged in a PELCO EasiGlow Cleaning System (Ted Pella, Redding, CA). A 3 µl drop of a sample was deposited onto the grid, blotted for 3 seconds with an offset of −3 mm, and vitrified in liquid ethane using the Vitrobot Mark III (FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands). Prior to vitrification, the sample chamber was maintained at 22 °C and 100% relative humidity to prevent sample evaporation. Grids were transferred to a Gatan 626 cryoholder (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA) and imaged on a FEI Tecnai G2 Twin TEM (FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands).

Determination of CMC

CP-PTX was further characterized by fluorescence spectroscopy using pyrene as a probe of the local hydrophobicity, which enables measurement of the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of CP-PTX micelles51. The ratio of the first fluorescence emission peak (I370–373) and the third peak (I381–384) were plotted over a range of CP concentrations. The sigmoid of best fit was used to calculate the CMC, defined as the inflection point of the curve.

pH Dependent Drug Release

To assay for the release of drug, samples of CP-PTX (1 mg.mL−1) were resuspended in pH 5.3 and 6.5 (with 50 mM Na2CO3) or pH 7.4 (0.1 M NaPO4) and finally diluted with acetonitrile in a volume ratio of acetonitrile:aqueous solution (0.33/1.0) (v/v). Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 0.0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 6, or 24 hs and quenched by dilution 1:1 [vol:vol] into pH 7.4 (0.1 M NaPO4) to return the pH to above 7.0 and thereby stop hydrolysis prior to the assay. The solution was then centrifuged at 4 °C for 1 min and stored at −80 °C. Sample preparation: Aliquots of 20 µL of the above samples were mixed with 20 µL of the deuterated Paclitaxel (PTX-d5) (internal standard) and 400 µL of deionized water. After liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) of analytes by 1mL of tert-butylmethylether, the top (ether) layer was removed and solvent evaporated under a gentle stream of nitrogen. The residue was reconstituted in 100 µL of 10% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water. LC conditions: Column: Agilent, Eclipse Plus C18, 4.6 × 50 mm, 1.8 µm particle size, at 40 °C; mobile phase A: 98:2 H2O:acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid); mobile phase B: acetonitrile; elution gradient: 0–1 min 5–95% B, 1–2 min 95% B, 2-2.2 min 95-5% B; run time: 5 min. ESI-MS/MS conditions: Electrospray parameters (e.g., declustering potential, temperature, gas flow) and mass spectrometer parameters (e.g., selection of parent/daughter ions, quadrupole potential) were optimized by direct infusion of pure analytes into the ESI-LC/MS system (Supplementary Figure 7). MRM transitions (m/z units) monitored were: PTX 854.3/285.7, PTX-d5 (internal standard) 859.3/290.7, PTX-LEV 952.5/383.6. Calibration samples in 9.72 – 1200 ng/mL (PTX and PTX-LEV) ranges were prepared by adding known amounts of pure analytes into plasma or tissue homogenate and were analyzed along with study samples. Linear response was observed in the concentration ranges measured.

In vitro Cytotoxicity

MDA-MB-231 human triple negative breast cancer cells and PC3 (PC-3M–luc-C6) human prostate cancer cells were purchased from Duke Cell Culture Facility and PerkinElmer Health Sciences, Inc. respectively and are maintained in complete media consisting of Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (MEME) (MDA-MB-231) or Gibco 11095 (PC3) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 5 mM sodium pyruvate, 5 mM non-essential amino-acid mixtures. PC3 were screened for Ectromelia, EDIM, Hantaan, LCMV, LDEV, MHV, MNV, MPV, MVM, Mycoplasma pulmonis, Mycoplasma sp., Polyoma, PVM, REO3, Sendai, TMEV GDVII. The result is negative to all pathogen mentioned above. The cell line authentication screening was done by IDEXX BioResearch using the following process: Authentication Process: Cell Check 9 multiplex PCR analysis using primers specific for mouse, rat, human, African green monkey and Chinese hamster genomic DNA allows confirmation of the species of origin of a given cell line and enables as little as 1–5% inter-species DNA contamination to be detected. PC3 cell lines was also genetically authenticated using microsatellite marker (STR) analysis which also allows intra-species contamination to be detected. The PC3 reference profile was used to authenticate the PC-3M–luc-C6 line. Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and passaged every 3 days. In vitro cytotoxicity was determined by= a colorimetric assay, as follows. 1–5 × 103 MDA-MB-231cells or PC3 cells were seeded per 100 µL media on BD Falcon™ 96-well cell culture plates (BD; Franklin Lakes, NJ) and allowed to adhere for 16–18 h. The cell media was then removed and replaced with 100 µL complete media containing PTX, Abraxane, CP-PTX nanoparticles and incubated at 37 °C for 72 h. The plates were then removed and 20 µL of CellTiter 96 AQueous™ (Promega; Madison, WI) 3-(4,5,-dimethyl2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H–tetrazolium (MTS) reagent was added to each well. Following incubation for 2 h, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 490 nm with a Victor3 microplate reader (Perkin Elmer; Waltham, MA). To calculate the IC50, the data was fit to the equation: viability = 1/(1 + (CP-PTX/IC50)p), where CP-PTX is the effective PTX concentration in the well, the IC50 is a measure of the dose needed to kill 50% of the cell population, and p represents the slope of the sigmoidal curve.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cells grown in 6-well plates for 24 h were treated with 1 nM free PTX or drug equivalent of CP-PTX for 24 h at 37°C. The drug was then removed by aspiration of the liquid, and replaced with drug-free media. Cells were cultured for another 24 h, and both floating and adherent cells were collected. Adherent cells were collected by trypsinization. For cell cycle analysis, the cell pellet was washed with cold PBS and fixed with 300 µL cold 70% ethanol for 20 min. After fixation, the cells were collected by centrifugation, washed with PBS and resuspended in 350 µL PBS. Cells were treated with 10 mg/mL of RNase A (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 30 min and then with 200 µg/mL of propidium iodide (PI) (Biolegend, CA) for 30 min. PI fluorescence was measured by a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer and analyzed by FlowJo software (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). A plot of forward scatter vs. PI intensity was used to eliminate cell debris and cell aggregates from the analysis. Fluorescence was measured for a sample of 5,000–10,000 cells, and histograms of cell number versus PI intensity were used to determine the percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at 2x104 cells per well on an 8 well coverglass slide (Electron Microscopy Sciences; Hatfield, PA). After 24 h, cells were treated with 1 nM PTX, or an equivalent concentration of CP-PTX for 1 h at 37 °C or 42 °C. The compounds were removed and cells were grown in complete media at 37 °C for 24 h or 72 h. Cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed with PBS + 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA). Following permeabilization with PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100, cells were blocked with PBS + 1% goat serum + 0.5% Tween 80 for 30 min at room temperature under humidified condition. Cells were stained with a 1:50 dilution of mouse anti-α-tubulin-FITC antibody (Millipore, MA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing thrice with PBS, the media was replaced with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 5 µg/ml Alexa Fluor 594 wheat agglutinin and 2 µM Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen; Grand Island, NY) to stain the cell membrane and nuclei, respectively. After 10 min, cells were washed thrice with PBS before the addition of HBSS. The cells were imaged immediately on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope, using a 63X water immersion objective.

Prior to in vivo implantation, cells were resuspended twice in Minimum Essential Media (MEM) (51200-038; Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). MDA-MB-231 cells were administered either in the right flank or mammary fat pad of female nude mice by subcutaneous injection of 6x106 cells in a 50 µL volume for subcutaneous and orthotropic tumors. For the PC3 tumor model, 2x106 cells in a 50 µL volume were injected subcutaneously on the right flank of male nude mice. All animals were treated in accordance with National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under protocols approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Dose Escalation and Tumor Regression

MDA-MB-231 tumor model: Female nude mice (6–8 weeks old) bearing subcutaneous or orthotopic MDA-MB-231 tumors were treated when the mice had a tumor volume of 75–100 mm3. Controls or drugs were administered by the tail vein infusion (50 µL/min) of 500 µL. Dose escalation was performed with free drug and CP-PTX at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 mg.kg−1 BW (BW: body weight) and 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 mg.kg−1 BW respectively. For the subcutaneous MDA-MB-231 model, mice were treated with 25 mg.kg−1 BW free PTX or, 30 mg.kg−1 BW CP-PTX and for orthotopic tumors; mice were treated with either 25 mg.kg−1 BW free PTX, 50 mg.kg−1 BW CP-PTX, 1.5 mM ELP (equivalent dose of ELP compared to 50 mg.kg−1 BW CP-PTX) or 50 mg.kg−1 BW Abraxane. PC3 Tumor Model: Male nude mice (6–8 weeks old) bearing subcutaneous PC3 tumors were treated when the mice had a tumor volume of 75–100 mm3. Controls or drugs were administered by the tail vein infusion (50 µL/min) of 500 µL. Mice were treated with either 25 mg.kg−1 BW free PTX or, 50 mg.kg−1 BW CP-PTX or, 50 mg.kg−1 BW Abraxane. Tumor dimensions and BW were measured 3–4 times a week, and the tumor volume was calculated according to Volume [mm3] = length × width × width × 1/2.

Mice were monitored for BW loss and euthanized upon exceeding 15% loss in BW or if their tumors grew to a volume greater than 1000 mm3. The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was determined in mice with tumors. Cumulative survival curves were compared using Kaplan-Meier analysis and the Sidak test, Tukey Test, Wilcoxon test were determined using GraphPad Prism 6 software.

Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution

To measure pharmacokinetics (PK), CP-PTX, Abraxane was intravenously infused into female nude mice (20 mg Dox equiv.kg−1 BW) via the tail vein. A blood sample (20 µL) was collected from the tail vein at 1, 15, and 30 min, and at 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 and 48 h after infusion and diluted into PBS with heparin (1,000 U mL−1). The blood was centrifuged (1,500 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C) and divided into two parts. Analysis of CP-PTX was accomplished by sample digestion by Proteinase K (non-selective proteinase) and subsequent measurement of a digestion product, fragment 1 (Frag1). Frag1 or, [PTX-LEV-EMCH-Cys-Gly-Gly]2+ ion, was identified as the most suitable fragment after qualitative enhanced spectral-mass analysis of the Proteinase K-digested CP-PTX and subsequent optimization of the digestion conditions (duration and temperature). In undigested samples, PTX and PTX-LEV (product of physiological digestion of ELP-PTX) were measured in a separate analytical run. All measurements were performed on a liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization/tandem-mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) instrument consisting of a Shimadzu 20A series liquid chromatography (LC) system and an Applied Biosystems MDS Sciex 4000 QTrap tandem-mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization (ESI-MS/MS) operated in multiple reactions monitoring (MRM) mode within Analyst v. 1.4.2 software. CP-PTX sample preparation: Aliquots of 5 µL of plasma or 30 µL of tissue homogenate (1 part tissue (grams) + 2 parts deionized water (mL) were mixed with 10 µL of the PTX-d5 (internal standard) and 50 µL of 500 µg/mL freshly prepared proteinase K in Tris buffer pH 7.4, incubated at 55°C for 3 h, and then diluted with 100 µL of deionized water. Solid-phase extraction (SPE): (1) cartridge conditioning: 2 x 1 mL MeOH + 2 x 1mL H2O, (2) transfer of the incubated sample into the cartridge, (3) rinsing: 2x1 mL H2O, (4) elution: 0.75 mL 100% MeOH. The solvent was evaporated and residue reconstituted in100 µL of 10% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water. PTX, Abraxane and PTX-LEV sample preparation: Aliquots of 20 µL of plasma or tissue homogenate (1 part tissue (g) + 2 parts water (mL); tough tissues cryo-crushed before homogenization) were mixed with 20 µL of the PTX-d5 (internal standard) and 400 µL of deionized water. After liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) of analytes by 1 mL of tert-butylmethylether, the top (ether) layer was removed and solvent evaporated under a gentle stream of nitrogen. The residue was reconstituted in 100 µL of 10% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water. LC conditions: Column: Agilent, Eclipse Plus C18, 4.6 x 50 mm, 1.8 µm particle size, at 40 °C; mobile phase A: 98:2 H2O:acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid); mobile phase B: acetonitrile; elution gradient: 0–1 min 5–95% B, 1–2 min 95% B, 2-2.2 min 95-5% B; run time: 5 min. ESI-MS/MS conditions: Electrospray (e.g. declustering potential, temperature, gas flow) and mass spectrometer (parent/daughter ions, quadrupole potential) parameters were optimized by direct infusion of pure analytes into the ESI-LC/MS system (Supplementary Figure 9). MRM transitions (m/z units) monitored: PTX 854.3/285.7, PTX-d5 (internal standard) 859.3/290.7, CP-PTX (as Frag1) 695.4/523.8, PTX-LEV 952.5/383.6. Calibration samples in 9.72 – 1200 ng/mL (PTX and PTX-LEV- plasma), 8.75 – 324 ng/mL (PTX and PTX-LEV- tissue), 125 – 1000 ng/mL (ELP-PTX - plasma), and 12.15 – 1500 ng/mL (ELP-PTX - tissue) ranges were prepared by adding known amounts of pure analytes into plasma or tissue homogenate and were analyzed along with study samples (Supplementary Figure 10–Supplementary Figure 12). Linear response was observed in the concentration ranges measured.

To obtain estimates and confidence intervals of pharmacokinetic parameters describing this behavior, the dataset was fit to a two-compartment pharmacokinetic model using SAAMIITM (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). The plasma concentration (n=4) was fit to determine the initial volume of distribution, V0, and t1/2, CL, Vss (Supplementary Table 4). From these data and the dose, D, other pharmacokinetic parameters were determined including the clearance:

Units, estimates, and confidence intervals for the above fit are all presented in Supplementary Table 4.

To quantify PTX tissue distribution, Abraxane, free drug or CP-PTX was injected at 20 mg PTX equivalent/kg BW via the tail vein. At 10 min, 1 h, 4 h, and 24 h after infusion, tumor, blood, and tissue samples were obtained. Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture using a heparinized needle, and plasma was isolated following centrifugation of blood (14,000 RPM, 10 min, 4 °C). Tissue drug concentrations were compared using Two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s test determined using GraphPad Prism 6 software.

Gene Expression Analysis

MDA-MB-231 tumor inoculation and drug administration were the same as described for the in vivo tumor regression study. When the tumor volume reached 50–75 mm3 (for CP-PTX response and PTX response) or, ~200 mm3(for control, ELP, CP-PTX relapse and PTX relapse) orthotopic tumors were collected and immediately mixed with RNAlater reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and kept frozen at −80 °C. Total RNA was later isolated from the tumor tissues by using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Integrity of the RNA samples was checked by RNA electrophoresis and gel analysis with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). The RNA samples were processed and probes were generated and hybridized to Affymetrix U133A arrays by the Duke University Microarray Facility according to manufacturer’s instruction. CEL files of all samples were normalized by RMA using Expression console (Affymetrix), zero-transformed against the average expression levels of the same probe sets of the vector-expressing control HSMMs, filtered by indicated criteria, clustered with cluster 3.0, and displayed with treeview as previously described52. The data were then formatted for zero-transformation and GSEA analysis using the Broad public server. All the microarray data are MIAME-compliant and have been submitted into GEO with accession number GSE3614.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Wenge Liu, Pichet Praveschotinunt and Cassie Caudill for their help. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 EB000188 and R01 EB007205) to A.C., (CA125618, and CA106520) to J.T.C. and Department of Defense (W81XWH-12-1-0148, W81XWH-14-1-0309 and W81XWH-15-1-0027 to JTC). We would like to thank the Duke Microarray Core facility for their technical support, microarray data management and feedback on the generation of the microarray data reported in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest A.C. has a financial interest in a start-up company, PhaseBio Pharmaceuticals that has licensed the technology reported herein from Duke University.

Author Contributions J.B. and A.C. conceived and designed the experiments. J.B. and J.J.B., J.R.M., I.W., I.S., and X.L., performed the experiments, C-C.L. and J.T.C. analyzed the gene expression data, and J.B. and A.C. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Scott RB. Cancer chemotherapy-the first twenty-five years. Br. Med. J. 1970;4:259–265. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5730.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CC, MacKay JA, Frechet JMJ, Szoka FC. Designing dendrimers for biological applications. Nature Biotechnol. 2005;23:1517–1526. doi: 10.1038/nbt1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: Mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDaniel JR, et al. Self-Assembly of Thermally Responsive Nanoparticles of a Genetically Encoded Peptide Polymer by Drug Conjugation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:1683–1687. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacKay JA, et al. Self-assembling chimeric polypeptide-doxorubicin conjugate nanoparticles that abolish tumours after a single injection. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:993–999. doi: 10.1038/nmat2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slichenmyer WJ, Von Hoff DD. New natural products in cancer chemotherapy. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1990;30:770–788. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1990.tb01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bombuwala K, et al. Colchitaxel, a coupled compound made from microtubule inhibitors colchicine and paclitaxel. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2006;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1860-5397-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tejada-Berges T, Granai CO, Gordinier M, Gajewski W. Caelyx/Doxil for the treatment of metastatic ovarian and breast cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2002;2:143–150. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gradishar WJ. Albumin-bound paclitaxel: a next-generation taxane. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2006;7:1041–1053. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.8.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tatham AS, Shewry PR. Elastomeric proteins: biological roles, structures and mechanisms. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:567–571. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Purification of recombinant proteins by fusion with thermally-responsive polypeptides. Nature Biotechnol. 1999;17:1112–1115. doi: 10.1038/15100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massey J, Power KN, Manners I, Winnik MA. Self-Assembly of a Novel Organometallic−Inorganic Block Copolymer in Solution and the Solid State: Nonintrusive Observation of Novel Wormlike Poly(ferrocenyldimethylsilane)-b-Poly(dimethylsiloxane) Micelles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9533–9540. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai N. Challenges in Development of Nanoparticle-Based Therapeutics. AAPS J. 2012;14:282–295. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9339-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardone RA, Casavola V, Reshkin S. The role of disturbed pH dynamics, the a+/H+ exchanger in metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:786–795. doi: 10.1038/nrc1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorkin A, von Zastrow M. Signal transduction and endocytosis: close encounters of many kinds. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:600–614. doi: 10.1038/nrm883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosch A, Eroles P, Zaragoza R, Viña JR, Lluch A. Triple-negative breast cancer: molecular features, pathogenesis, treatment and current lines of research. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2010;36:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudis CA, Gianni L. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: An Unmet Medical Need. The Oncologist. 2011;16:1–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-S1-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang TH, Wang HS, Soong YK. Paclitaxel-induced cell death: where the cell cycle and apoptosis come together. Cancer. 2000;88:2619–2628. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000601)88:11<2619::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singla AK, Garg A, Aggarwal D. Paclitaxel and its formulation. Int. J. Pharm. 2002;235:179–192. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00986-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowinsky EK, Chaudhry V, Cornblath DR, Donehower RC. Neurotoxicity of Taxol. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 1993;15:107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U. S. Food & Drug Administration. New Drug Application Pharmacology Review 21-660. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 2004 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2005/21660_ABRAXANE_pharmr.PDF.

- 23.Li C, et al. Biodistribution of paclitaxel and poly(L-glutamic acid)-paclitaxel conjugate in mice with ovarian OCa-1 tumor. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2000;46:416–422. doi: 10.1007/s002800000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang X, et al. Functional interaction between responses to lactic acidosis and hypoxia regulates genomic transcriptional outputs. Cancer Res. 2012;72:491–502. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JL-Y, et al. Lactic acidosis triggers starvation response with paradoxical induction of TXNIP through MondoA. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:1001093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. AcadSci. U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shelley WB, Talanin N, Shelley ED. Polysorbate 80 hypersensitivity. Lancet. 1995;345:1312–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90963-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K, Sparreboom A. Cremophor EL: the drawbacks advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. J. Eur. Cancer. 2001;37:1590–1598. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma A, Sharma US, Straubinger RM. Paclitaxel-liposomes for intracavity therapy of intraperitoneal P388 leukemia. Cancer Lett. 1996;107:265–272. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(96)04380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim WT, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic study of a weekly liposomal paclitaxel formulation (Genexol-PM) in patients with solid tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2010;21:382–388. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamaguchi T, et al. NK105 a paclitaxel-incorporating micellar nanoparticle formulation, can extend in vivo antitumour activity, reduce the neurotoxicity of paclitaxel. Br. J. Cancer. 2005;92:1240–1246. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaucher G, Marchessault RH, Leroux JC. Polyester-based micelles nanoparticles for the parenteral delivery of taxanes. J. Control. Release. 2010;143:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Letchford K, Liggins R, Wasan KM, Burt H. In vitro human plasma distribution of nanoparticulate paclitaxel is dependent on the physicochemical properties of poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(caprolactone) nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009;71:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gradishar WJ, et al. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castoroil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:7794–7803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harries M, Ellis P, Harper P. Nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel for metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:7768–7771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nyman DW, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetics trial of ABI-007, a novel nanoparticle formulation of paclitaxel in patients with advanced non hematologic malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:7785–7793. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.6148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miele E, Spinelli GP, Miele E, Tomao F, Tomao S. Albumin-bound formulation of paclitaxel (Abraxane ABI-007) in the treatment of breast cancer. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2009;4:99–105. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ernsting MJ, et al. A docetaxel-carboxymethylcellulose nanoparticle outperforms the approved taxane nanoformulation, Abraxane, in mouse tumor models with significant control of metastases. J. Control. Release. 2012;162:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boddy AV, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of paclitaxel poliglumex (XYOTAX), investigating both 3-weekly and 2-weekly schedules. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:7834–7840. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li C, et al. Complete regression of well-established tumors using a novel water-soluble poly(L-glutamic acid)-paclitaxel conjugate. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2404–2409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao TL, et al. Site-specific chemical modification of human serum albumin with polyethylene glycol prolongs half-life and improves intravascular retention in mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012;35:280–288. doi: 10.1248/bpb.35.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zasadil LM, et al. Cytotoxicity of Paclitaxel in Breast Cancer Is due to Chromosome Missegregation on Multipolar Spindles. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:229–243. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu W, et al. Tumor accumulation, degradation, pharmacokinetics of elastin-like polypeptides in nude mice. J. Control. Release. 2006;116:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shamji MF, et al. Development and characterization of a fusion protein between thermally responsive elastin-like polypeptide and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: sustained release of a local antiinflammatory therapeutic. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3650–3661. doi: 10.1002/art.22952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang X, Jain PK, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Gold nanoparticles: Interesting optical properties and recent applications in cancer diagnostics and therapy. Nanomedicine(Lond) 2007;2:681–693. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.5.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin CR, Kohli P. The emerging field of nanotube biotechnology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:29–37. doi: 10.1038/nrd988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duncan R. Polymer conjugates as anticancer nanomedicines. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:688–701. doi: 10.1038/nrc1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gillies RJ, Raghunand N, Karczmar GS, Bhujwalla ZM. MRI of the tumor microenvironment. J. MagnReson. Imaging. 2002;16:430–450. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guda C, et al. Hyperexpression of an environmentally friendly synthetic polymer gene. Biotechnol. Lett. 1995;17:745–750. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Etrych T, Sírová M, Starovoytova L, Rihova B, Ulbrich K. HPMA Copolymer Conjugates of Paclitaxel and Docetaxel with pH-Controlled Drug Release. Mol. Pharm. 2010;7:1015–1026. doi: 10.1021/mp100119f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao CL, Winnik MA, Riess G, Croucher MD. Fluorescence probe techniques used to study micelle formation in water-soluble block copolymers. Langmuir. 1990;6:514–516. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chi JT, et al. Gene Expression Programs in Response to Hypoxia: Cell Type Specificity and Prognostic Significance in Human Cancers. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e47. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.