Abstract

Despite the demonstrated benefit from epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) based therapies, EGFR mutant lung adenocarcinoma will eventually acquire drug resistance. Transformation to small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is considered to be a rare resistance mechanism of EGFR-TKI therapy.

We describe a case of a 46-year-old man presenting with refractory cough. Percutaneous transthoracic biopsy was performed and confirmed an EGFR exon 21 L858R lung adenocarcinoma. However, the patient relapsed after successful treatment with gefitinib for 1 year, at which point rebiopsy identified an SCLC and chemotherapy composed of platinum and pemetrexed was started. However, despite the brief success of chemotherapy, our patient died of aggressive cancer progression and complications of chemotherapy.

Our case highlights the importance of rebiopsy when managing drug resistance and presents a possible origin of the transformed cells. We also summarize the clinical characteristics of cases involving transformed SCLC from previous studies and discuss whether it could be a new subtype of SCLC.

INTRODUCTION

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are highly promising and commonly used drugs that are well tolerated and have good antitumor activity in patients with sensitive mutations in the EGFR gene identified in specimens regarded as nonsmall-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1 These patients tend to have better responses to EGFR inhibitors, although unfortunately their disease will ultimately develop drug resistance, which, despite extensive research, remains to be solved. The EGFR T790 M mutation, MET amplification, and histologic transformation including SCLC transformation, have all been suggested as possible mechanisms of TKI resistance. Herein, we report a case of TKI resistance due to SCLC transformation, and review 18 previous reports to establish whether SCLC transformation is related to specific clinical characteristics and if it represents a new SCLC subtype.

CASE PRESENTATION

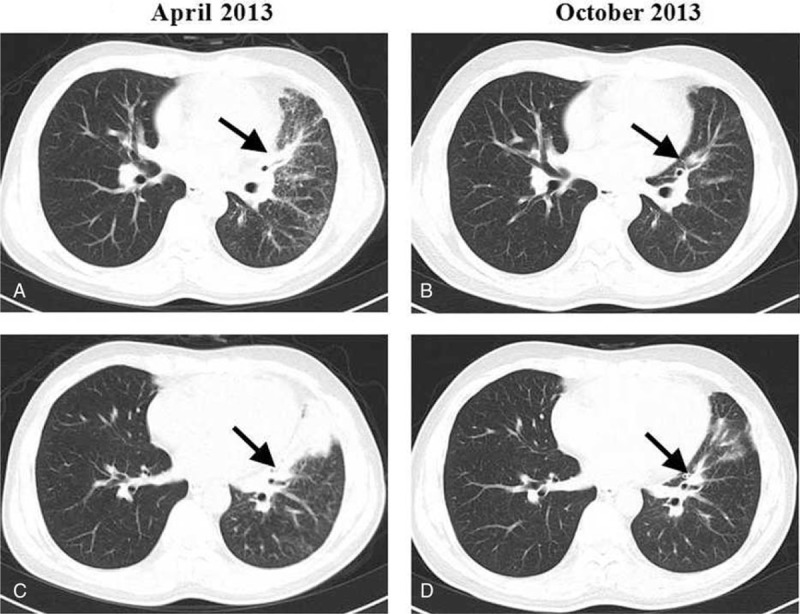

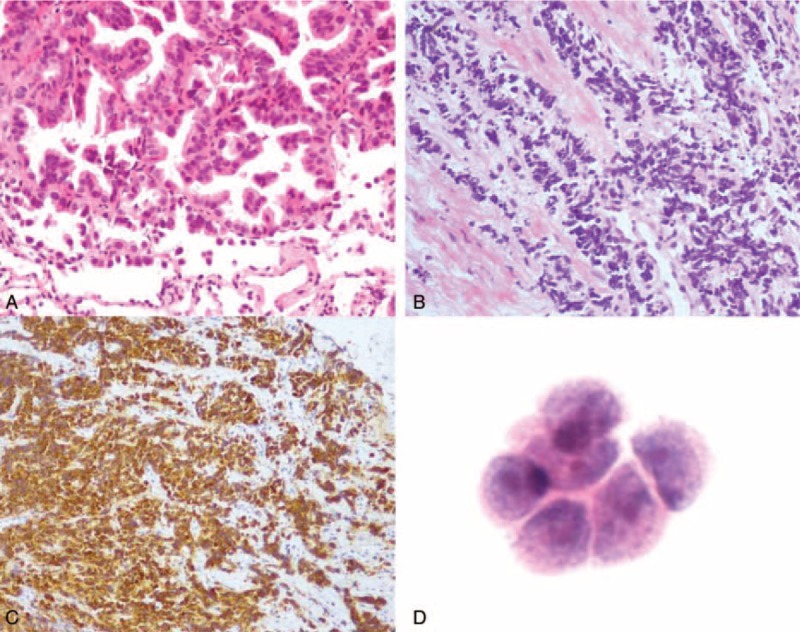

A 46-year-old Chinese man with no smoking history presented to our department complaining of a cough in December 2012. Computed tomography (CT) revealed patchy shadows in the left lung, which were obvious in the lingular segment (Figure 1A). The patient was administered several antibiotics to treat the suspected infection, although he did not report any improvement in his symptoms. A positron emission tomography18/CT (PET/CT) scan revealed a 50 mm × 28 mm sized mass in the upper lobe of the left lung with intense uptake of (18F) fluorodeoxyglucose, and hypermetabolic pulmonary nodule deposits in both the left lung and left hilar. Hypermetabolic mediastinal (2R, 4R, and 10L) lymph nodes and a hypermetabolic thoracic spine were also identified. A CT guided percutaneous pulmonary biopsy was therefore performed, the findings of which confirmed the diagnosis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (Figure 2A). This biopsy sample was genotyped and an EGFR exon 21 L858R mutation was identified using an amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS)-PCR method. The patient was therefore immediately started on gefitinib treatment along with radiotherapy to the thoracic spine. Within 10 months of gefitinib treatment, he had achieved excellent radiological partial remission (Figure 1B) evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines.

FIGURE 1.

CT axial sections showing (A) baseline adenocarcinoma and (B) partial remission upon gefitinib treatment.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Before treatment, the lung biopsy shows adenocarcinoma, tumor cells are median-sized, with an obvious atypical appearance, abundant cytoplasm, and nuclear division, and are arranged in papillary and acinus along fibrovascular cores. (B) The recurrent tumor contains small cells arrange in a prominent nesting pattern with neuroendocrine morphology and (C) diffuse positive staining for Syn. (D) Adenocarcinoma cells found in cerebrospinal fluid. (A and B) ×300 H&E (hematoxylin and eosin); (C) ×150 Syn IHC (immunological histological chemistry); (D) ×400 H&E.

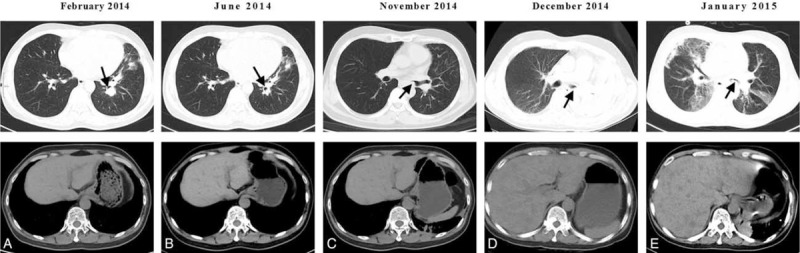

In February 2014 a CT scan revealed a new nodule measuring 15 mm × 17 mm in the lower lobe of the left lung (Figure 3A). The patient underwent a bronchoscopy examination that revealed a mass in the subsegmental bronchi of the lateral basal segment of the left lower lobe, which was sampled using a transbronchial biopsy. Meanwhile, second line chemotherapy consisting of platinum and pemetrexed was initiated while waiting for the pathological results. Reimaging 2 months later demonstrated a partial remission (Figure 3B). The previous biopsy suggested SCLC, and immunohistochemical analysis of the new biopsy confirmed this diagnosis with focally positive staining for AE1/AE3, positive staining for TTF-1 and Syn, and negative staining for LCA, CD56, and CgA, and a Ki-67 index of 85% (Figure 2B and C). As there had been a favorable response to platinum-pemetrexed based treatment, this was continued for another 4 cycles and completed in June 2014. The patient was then immediately restarted on targeted therapy with gefitinib and had regional radiation 30 times to a total dose of 60 Gy to his tumor in the left lower lobe, which was completed by September. He started to complain of an increasingly severe cough in November, at which time a CT scan showed multiple patchy consolidations, a shadow, and nodules in both the upper and lower lobe of the left lung (Figure 3C). In addition, contralateral small nodules, thickening of the wall of the main left bronchus and several low-density shadows in the liver were observed. Radiation pneumonitis was diagnosed and the patient was started on glucocorticosteroid treatment. However, just after the CT scan, he began to suffer severe headaches 2 to 3 times a day. With these rapidly worsening headaches, he was almost bed-ridden and was readmitted to our hospital. The brain nuclear magnetic resonance (MR) imaging scan revealed cerebral and leptomeningeal metastases with ventriculomegaly, which was confirmed by the cytological findings (Figure 2D). The supernatant of his cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was positive for the EGFR 21L858R mutation based on digital-PCR results, but there was no evidence for the T790 M mutation. A CT scan showed left pulmonary atelectasis (Figure 3D). Mannitol was administered every 6 hours to alleviate his intracranial hypertension, at which time gefitinib treatment was discontinued and erlotinib was administered along with intrathecal injection of methotrexate (MTX). However, intrathecal treatment was halted due to liver damage (total bilirubin 25.4 μmol/L, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase 232 U/L). One week after the commencement of erlotinib treatment, the patient's headaches were relieved under the same dose of mannitol and he was able to engage in light physical labor. Shortly after, unfortunately, he presented severe hemoptysis most probably caused by the mass in the left main bronchus. The patient was treated with hemostasis that controlled the hemoptysis, but he then began to complain of a severe stomach pain that was found to be caused by numerous liver metastases. Based on the rapid development of liver metastases and the mass in the left main bronchus, we attributed these 2 metastases to the transformed SCLC. On December 24 a single cycle of reduced oral etoposide was administered. Six days after the chemotherapy, a CT scan evaluation (Figure 3E) showed progression in the liver despite left lung puffs when this patient suffered IV degree myelosuppression and subsequently suffered gastrointestinal hemorrhage. The tumor progressed to an extent that obstructed the left main bronchus and caused a second left atelectasis, which, together with a hospital acquired pulmonary infection, resulted in a rapid deterioration in his condition and finally led to his death on January 17, 2015.

FIGURE 3.

CT axial sections showing (A) early SCLC development, (B) response to platinum–pemetrexed treatment, (C) masses in the left main bronchus, (D) tumor progression (obstruction of the main bronchus of the left lung and multiple liver metastases), and (E) response to low-dose etoposide.

DISCUSSION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

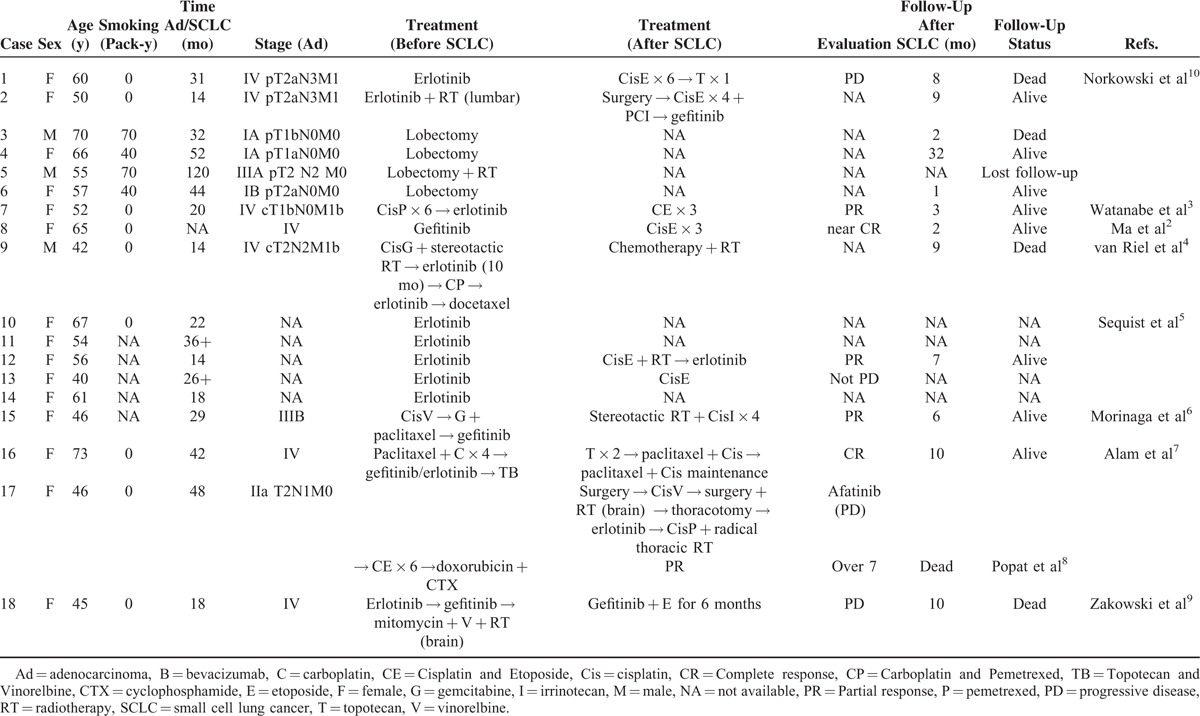

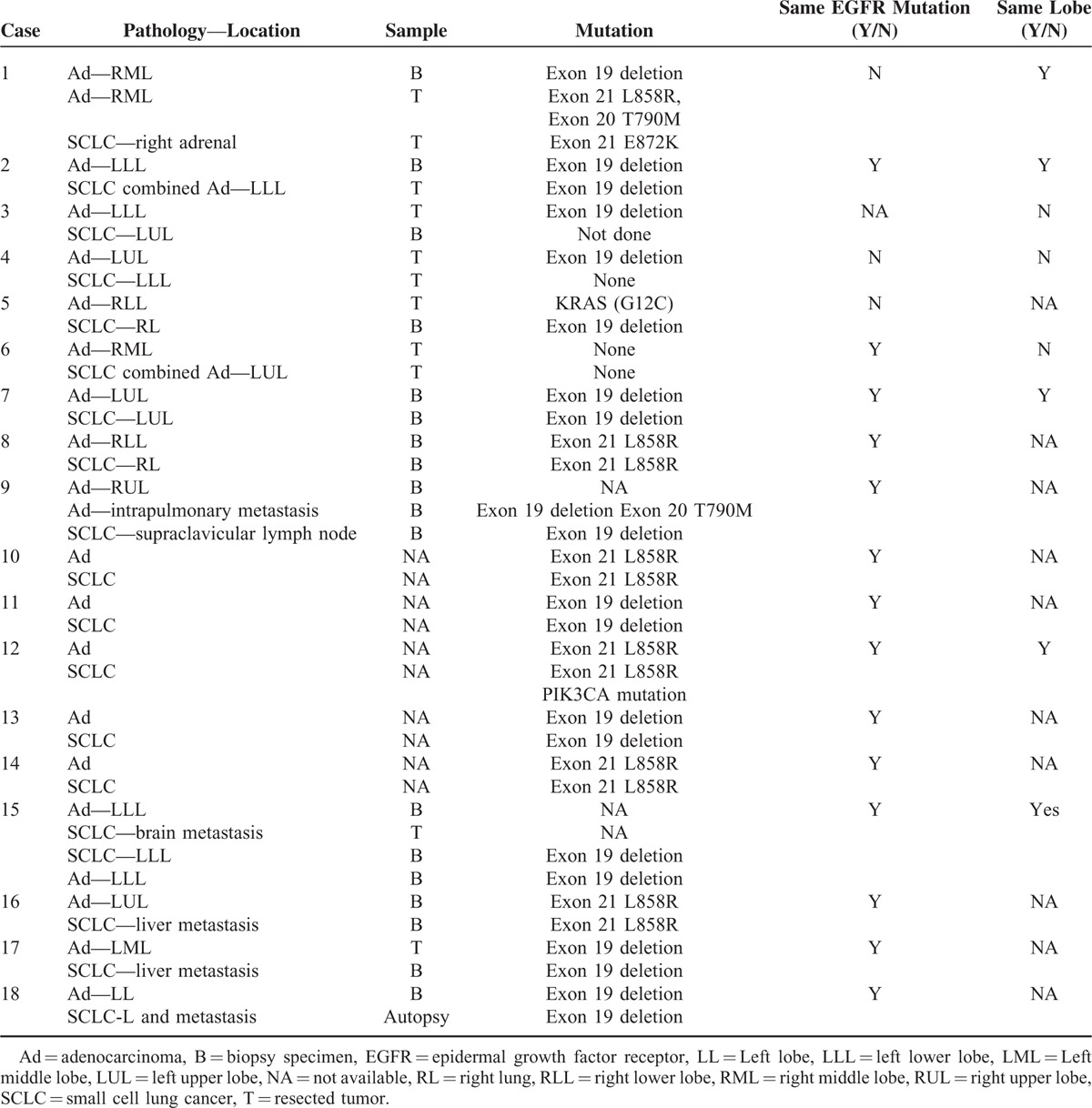

The patient in the case described here was a middle-aged nonsmoking Chinese man who was initially diagnosed with pulmonary adenocarcinoma. However, the disease transformed to SCLC and became resistant to gefitinib. After that, despite the brief success of chemotherapy (platinum and pemetrexed) for the SCLC and a clinical response of his brain metastases to combined erlotinib and intrathecal MTX treatment, he died of aggressive cancer progression and complications of chemotherapy. Chronologically, the second SCLC is always perceived as “transformed SCLC.” A review of the relevant literature in PubMed revealed 18 previously reported cases of sequential SCLC after adenocarcinoma (Table 1), involving 3 male and 15 female patients. Nine of the patients were nonsmokers and 4 were smokers, with an average age of 55 and 62 years old, respectively. Sixteen patients had activating EGFR mutations in their original adenocarcinoma, of who 11 (61%) had an exon 19 deletion mutation and 5 (28%) had the exon 21 point mutation L858R (Table 2). In the other 2 cases the NSCLC specimens were not found to harbor any EGFR mutations (cases 5 and 6). Amongst these 18 cases 5 patients were treated surgically, and 13 patients respond clinically to either gefitinib or erlotinib. One had a mixed response2 with clinical resolution of the supraclavicular and left axillary lymph nodes but increased right pleural effusion. Based on radiography findings, the 2 types of tumor (the original tumor and the transformed one) in 6 of the patients were found in the same lobe and in 4 patients, including our patient, they were located in different lobes. These patients appeared to have had variable disease courses based on the available data, SCLC tended to occur later in earlier stage of adenocarcinoma (I, II, IIIA) than in advanced ones (IIIB, IV) with an average interval of 59 months (range, 32–120 months) in the former and 20 months (range, 14–31 months) in the latter, indicating that disease stage could be a risk factor for phenotypic change.2–10 After development of the second cancer, 11 SCLCs carried the same EGFR mutation as their adenocarcinoma counterparts, and in the case reported by van Riel et al, the second cancer shared one of the original mutations. Interestingly, our case has some similar clinical features to previously reported cases involving nonsmoking patients, such as a comparatively young age, the type of EGFR mutation, advanced adenocarcinoma at first diagnosis, and a relatively short interval between the first and the second cancer.

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathologic Features of SCLC Associated With Lung Adenocarcinoma

TABLE 2.

Pathologic Features and Mutation Status of SCLC Associated With Lung Adenocarcinoma

SCLC transformation from adenocarcinoma in patients with an EGFR tumor mutation has been suggested as a mechanism of resistance to targeted therapy in several case reports (cases 7–9, 15–18),2–4,6–9 all of which described transformation to SCLC following or upon treatment with EGFR TKIs. This was supported by the findings of Sequist et al5 who conducted a more systematic study, in which such transformation was found to be responsible for TKI resistance in 5 cases (cases 10–14) and the original EGFR mutation was maintained. Based on the presence of the same mutation, these 2 lung cancers were considered metachronous and the subsequent SCLCs were believed to either evolve from the adenocarcinoma or develop from a common precursor. In either hypothesis, according to these reports, EGFR mutations may promote a phenotypic change in adenocarcinoma or the differentiation of SCLC from its precursors, especially when cancer cells are exposed to EGFR TKIs. Although this seems a reasonable assumption based on published cases, the underlying mechanism remains unclear. In addition, combined SCLCs were previously considered to be rare, with a reported occurrence of 1% to 3.2% of all SCLCs,11 the true proportion based on surgical specimens was found to be 9% to 26%. This suggests the combined data from previous case studies are limited because the pathological and genomic results of the second tumor are obtained through tissue biopsy instead of surgical resection, which could introduce sampling error.12 To overcome this, Norkowski et al10 included specimens excised from tumors in their study and demonstrated that among 6 patients with metachronous occurrence of SCLC after being diagnosed with adenocarcinoma, only 2 had a history of TKI use, and they therefore concluded that the incidence of SCLC in patients with adenocarcinoma is associated only with EGFR mutation status and not TKI use. They also concluded that metachronous SCLC could have different EGFR mutations from the previous adenocarcinoma (cases 1, 4, and 5).10 Their findings support the concept of tumor heterogeneity, that is, the differentiation of both cancers from pluripotent cells. Norkowski et al also suggested that the high proportion of EGFR mutations in tumors that underwent phenotypic change reinforced the hypothesis of a pluripotent population in EGFR-mutant cancer. However, in the available 18 published cases all 14 patients with advanced adenocarcinoma had been treated with an EGFR-TKI, and thus we can still infer that in advanced adenocarcinoma the use of an EGFR-TKI may activate pluripotent cells or drive a specific differentiation. To summarize, we postulate at least 3 mechanisms that could account for the switch between NSCLC and SCLC. Firstly, as described above, SCLC can result from the dedifferentiation of a previously well-defined cancer, which is similar to a mechanism known to occur in prostate cancer.13 The observed evolution of SCLC from NSCLC in patients who are not administered an EGFR-TKI and a shared mutation support this mechanism. The predisposition14 and TKI use may play a role in this dedifferentiation based on previous investigations and the findings of previous case studies, but the paucity and limitation of biopsy material needs to be considered. Furthermore, patients treated with EGFR-TKIs usually have advanced adenocarcinoma, which will probably have undergone a long series of differentiation events, so the effects of EGFR-TKIs in this transformation remain undetermined. Secondly, both NSCLC and SCLC could arise from the same cancer stem cell or progenitor cell. The adenocarcinoma can differentiate and present as the first cancer. The activation of specific signaling pathways can lead to dormant stem cells undergoing SCLC transformation.15 Thirdly, it is possible that the 2 components are both present at initial diagnosis but the limited material available for analysis means that some synchronous cancers are mistaken as metachronous cancer, which may explain the occurrence of some combined cancer without a clear differential interval.

In SCLC, the response rate of the standard regime (cisplatin or carboplatin plus etoposide) was reported to be 70% to 90% for limited-stage disease and 60% to 70% for extensive stage disease, and the corresponding overall survival was reported to be 14 to 20 months and 9 to 11 months, respectively. Among the 18 patients, 8 patients were reported to have received platinum-based chemotherapy and 7 of them received the standard regime composed of cisplatin/carboplatin and etoposide. In all 6 cases in which treatment efficacy was reported, only 1 involved disease progression despite administration of the standard regime, giving a response rate of 83%. However, of the patients with survival data who had undergone chemotherapy, the overall survival was only 7.1 months in SCLC, even after a favorable response. Our patient also responded to a platinum-based therapy, with an overall survival of 10 months. The patient who progressed after conventional chemotherapy declined quickly despite salvage chemotherapy, and autopsy later revealed only SCLC in the lung, thoracic lymph nodes, liver, and nodules along the diaphragm, and the original EGFR L858R mutation and adenocarcinoma were present in the brain metastases.5 The autopsy of another case unexpectedly revealed metastatic SCLC harboring the original mutation in multiple organs without any adenocarcinoma.9 It seems that conventional chemotherapy consisting of platinum and etoposide is effective initially and it is the development of SCLC that proves fatal, suggesting that clinicians should focus more on SCLC when treating these patients. Nevertheless, despite the limited number of patients and staging accuracy, it seems reasonable to infer that this transformed SCLC is comparatively aggressive even with effective treatment, which may be related to the overall condition of the patient and complications of chemotherapy. Some patients continued TKI treatment and began chemotherapy based on VP-16 after transformation (cases 2 and 18). However, the limited number of patients means that we cannot yet determine whether continued EGFR-TKI treatment brings any further clinical benefit. Based on the available clinical information, these transformed SCLCs carry a relatively poor prognosis compared with classic SCLC. In addition, all of the cases underscore the importance of incorporating repeated biopsies into clinical practice when EGFR-TKI resistance occurs. Taking the characteristics of the 18 patients into consideration, we suggest that, for patients who progress rapidly, especially those who are young, nonsmokers, and have EGFR mutations or mixed histology, SCLC transformation and rebiopsy should be considered when managing drug resistance,9,16 and frequent surveillance may be needed. Moreover, tumor biomarkers such as serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) combined with other biomarkers such as neuron specific enolase (NSE) and progastrin-releasing peptide (ProGRP) might allow the prognosis and therapeutic efficacy to be evaluated for NSCLC.17,18 These markers may also indicate disease progression or histological change, although whether they can accurately predict SCLC transformation or the existence of progenitor cells remains to be determined.

The case we report here poses a challenge with respect to the TNM classification and the proper treatment for transformed SCLC. Whether these patients benefit from concurrent chemoradiotherapy or PCI following traditional chemotherapy requires further study. Although there is evidence that separating SCLC into limited and extensive stages is of benefit, it could be inferred that reclassification of SCLC is necessary,19 especially for individuals with multiple cancer. These cases may represent a new subgroup with previous NSCLC, an EGFR mutation, no standard treatment, a poor prognosis, and short overall survival. Genome sequencing has revealed a high prevalence of mutations in the TP53 and RB1 genes in SCLC, suggesting that these mutations might have a role in transformation. In addition, it has been suggested that alveolar type II cells give rise to SCLC,20 and to understand the transformed subgroup better, further investigations are required to explore the molecular mechanisms of this transformation especially those involving the EGFR, RB1, and TP53 genes, and to identify the most appropriate treatment for these patients.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we have tried to provide some practical information regarding SCLC transformation in patients with pulmonary adenocarcinoma treated with EGFR-TKIs, and we suggest that cancers that undergo this transformation may represent a new subgroup of SCLC that requires further study.

Acknowledgments

The patient had given us his consent for this case report to be published. We thank Miss Yvonne Chan for English language editing.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor, PET = positron emission tomography, PET18/CT = 18F-fuorodexoyglucose-positron emission tomography computed tomography, RECIST = Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, SCLC = small-cell lung cancer, TKI = tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

S-YJ and JZ contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rossi A, Di Maio M. LUX-Lung: determining the best EGFR inhibitor in NSCLC? Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:118–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma AT, Chan WK, Ma ES, et al. Small cell lung cancer with an epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in primary gefitinib-resistant adenocarcinoma of the lung. Acta Oncol 2012; 51:557–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watanabe S, Sone T, Matsui T, et al. Transformation to small-cell lung cancer following treatment with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2013; 82:370–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Riel S, Thunnissen E, Heideman D, et al. A patient with simultaneously appearing adenocarcinoma and small-cell lung carcinoma harbouring an identical EGFR exon 19 mutation. Ann Oncol 2012; 23:3188–3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3:r26–r75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morinaga R, Okamoto I, Furuta K, et al. Sequential occurrence of non-small cell and small cell lung cancer with the same EGFR mutation. Lung Cancer 2007; 58:411–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alam N, Gustafson KS, Ladanyi M, et al. Small-cell carcinoma with an epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in a never-smoker with gefitinib-responsive adenocarcinoma of the lung. Clin Lung Cancer 2010; 11:E1–E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popat S, Wotherspoon A, Nutting CM, et al. Transformation to “high grade” neuroendocrine carcinoma as an acquired drug resistance mechanism in EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2013; 80:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zakowski MF, Ladanyi M, Kris MG, et al. EGFR mutations in small-cell lung cancers in patients who have never smoked. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:213–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norkowski E, Ghigna MR, Lacroix L, et al. Small-cell carcinoma in the setting of pulmonary adenocarcinoma: new insights in the era of molecular pathology. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8:1265–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mangum MD, Greco FA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Combined small-cell and non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1989; 7:607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholson SA, Beasley MB, Brambilla E, et al. Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC): a clinicopathologic study of 100 cases with surgical specimens. Am J Surg Pathol 2002; 26:1184–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker GE, Antoniono RJ, Ross HJ, et al. Neuroendocrine-like differentiation of non-small cell lung carcinoma cells: regulation by cAMP and the interaction of mac25/IGFBP-rP1 and 25.1. Oncogene 2006; 25:1943–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teicher BA. Targets in small cell lung cancer. Biochem Pharmacol 2014; 87:211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Angelo SP, Pietanza MC. The molecular pathogenesis of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 2010; 10:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukui T, Tsuta K, Furuta K, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status and clinicopathological features of combined small cell carcinoma with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer Sci 2007; 98:1714–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arrieta O, Villarreal-Garza C, Martinez-Barrera L, et al. Usefulness of serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in evaluating response to chemotherapy in patients with advanced non small-cell lung cancer: a prospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 2013; 13:254–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin HF, Qu LL, Liu H, et al. Serum CEA level change and its significance before and after Gefitinib therapy on patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013; 14:4205–4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowlati A, Wildey G. Defining subgroups of small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2014; 9:750–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oser MG, Niederst MJ, Sequist LV, et al. Transformation from non-small-cell lung cancer to small-cell lung cancer: molecular drivers and cells of origin. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:e165–e172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]