Abstract

The steroid hormone progesterone (P), acting via the progesterone receptor (PR) isoforms, PR-A and PR-B, exerts a profound influence on uterine functions during early gestation. In recent years, chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing in combination with microarray-based gene expression profiling analyses have revealed that the PR isoforms control a substantially large cistrome and transcriptome during endometrial differentiation in the human and the mouse. Genetically engineered mouse models have established that several PR-regulated genes, such as Ihh, Bmp2, Hoxa10, and Hand2, are essential for implantation and decidualization. PR-A and PR-B also collaborate with other transcription factors, such as FOS, JUN, C/EBPβ and STAT3, to regulate the expression of many target genes that function in concert to properly control uterine epithelial proliferation, stromal differentiation, angiogenesis, and local immune response to render the uterus ‘receptive’ and allow embryo implantation. This review article highlights recent work describing the key PR-regulated pathways that govern critical uterine functions during establishment of pregnancy.

Keywords: Progesterone receptor, implantation, endometrium, decidualization

Introduction

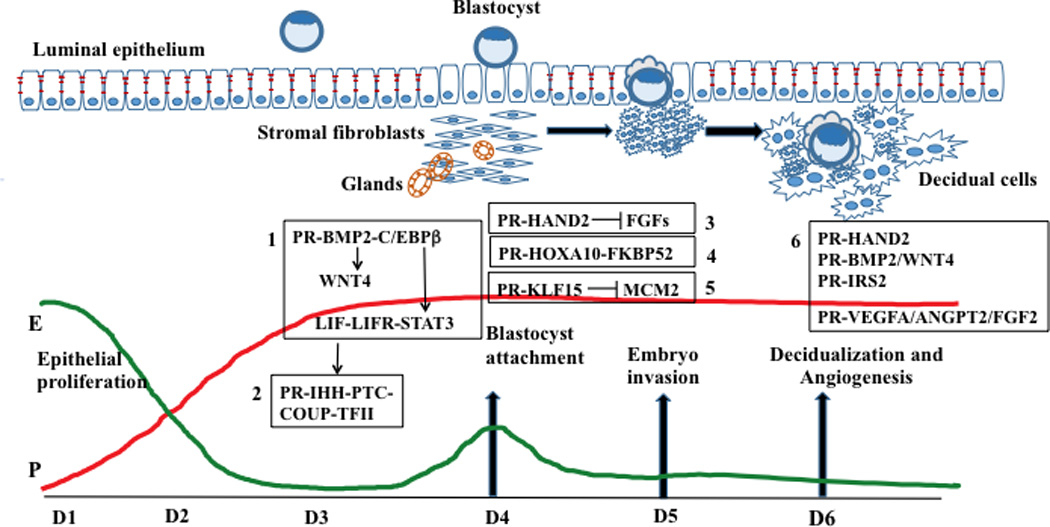

During implantation, the embryo attaches to the receptive uterine epithelium to initiate pregnancy.1–6 Later the embryo invades into the underlying endometrial stroma as the stromal cells are transformed into decidual cells, which support embryonic growth and survival. During establishment and maintenance of pregnancy, the steroid hormone progesterone (P) plays a central role by profoundly influencing endometrial functions. In the preimplantation phase, P acts in concert with 17β estradiol (E) to orchestrate changes in the uterine epithelium rendering it competent for embryo implantation.4, 6 In mice, ovarian E on days 1 and 2 of pregnancy stimulates proliferation of uterine epithelium. In this E-dominated phase, the epithelium displays distinct columnar phenotype and cell-cell contacts via intracellular tight and adherens junctions. In response to rising P levels, starting on day 3 of pregnancy, the uterine epithelium ceases to proliferate and begins to undergo differentiation. The luminal epithelium, upon differentiation, undergoes structural remodeling involving disruption of tight and adherens junctions, which facilitates embryo attachment and invasion.7, 8 On day 4 of pregnancy, as the embryo attaches to the luminal epithelium, the subjacent fibroblastic stromal cells undergo differentiation into unique secretory ‘decidual’ cells. P is the primary driver of this differentiation process, termed decidualization, which is a prerequisite to successful implantation.5, 6 In this review, we will highlight some of the recent studies that elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which P regulates the early steps leading to the acquisition of uterine receptivity for implantation and successful establishment of pregnancy (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A network of PR-dependent factors regulates critical events during embryo implantation.

The profiles of systemic progesterone (P) and 17β-estradiol (E) during days 1–6 (D1-D6) of pregnancy are shown. The major PR-regulated pathways controlling various phases of implantation are shown in boxes 1–6. Genetic evidence in the mouse supports a functional role for most of these factors in implantation. In some cases, functional evidence was obtained by employing human endometrial cultures. Box 1: PR controls the production of BMP2, which acts via BMP2 receptor 1 to induce C/EBPβ. C/EBPβ directly regulates STAT3, which serves as a downstream effector of LIF signaling via LIF receptor. BMP2 also controls WNT4 expression. Box 2: P drives IHH expression in the luminal epithelium. IHH acts on the stroma via the PTCH1 receptor to promote decidualization through activation of COUP-TFII signaling. Box 3: P, acting through PR in the stroma, promotes HAND2 expression. HAND2 inhibits the expression of FGFs, thereby blocking epithelial proliferation. Box 4: PR induces the expression of HOXA10, which in turn promotes stromal proliferation and differentiation by inducing the expression of FKBP52, a chaperon for ER and PR. Box 5: PR-dependent KLF15 expression inhibits MCM2 which critically controls epithelial proliferation. Box 6: Several PR-regulated stromal factors, such as HAND2, BMP2, WNT4, and IRS2, control decidualization. Other PR-regulated factors, such as VEGFA, ANGPT2, and FGF2, play important roles in angiogenesis.

The physiological effects of P are mediated by the intracellular progesterone receptors (PRs). There are two isoforms of PR, PR-A and PR-B, generated from alternate transcripts arising from a single gene via different promoter usage.9 Both isoforms have the same DNA binding and ligand binding domains, but PR-B possesses an additional transactivation domain in the amino terminal region. The PRs are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily.10, 11 In the presence of P, PR dissociates from the heat shock chaperone proteins, undergoes dimerization, and binds to target genes via direct interaction with discrete DNA response elements or via tethering interactions with other transcription factors. At the target gene, PR-A and PR-B recruit co-regulators to control transcription.10, 12 They also interact with transcription factors, such as FOS, JUN, CEBPβ and STAT3, which bind to neighboring genomic sites and modulate their transcriptional activities.13, 14 During human endometrial stromal decidualization, PR-B controls a substantially larger cistrome and transcriptome than PR-A.13 PR-B also directly regulates the expression of PR-A.13

Lydon et al 15 developed the PR knockout (PRKO) mouse, which lacks both PR-A and PR-B. This model provided important insights into the crucial role played by PR in mediating P-regulated responses during early pregnancy. The PRKO mice are infertile due to ovulation defect, since PR signaling in granulosa cells of the ovary is essential for conducting the luteinizing hormone-induced ovulatory program.15 In addition to this ovarian phenotype, the PRKO mice also exhibited hyperplastic uteri that are non-receptive to embryo implantation. Analysis of these uteri revealed impaired decidualization and hypertrophied epithelium that is infiltrated by leucocytes.15 Interestingly, genetic manipulations in mice leading to ablation of PR-A but not PR-B expression resulted in a uterine phenotype similar to PRKO, indicating that PR-A is the major isoform involved in the regulation of uterine receptivity and decidualization in the mouse.16 However, in the human, PR-B plays a dominant role during decidualization.13

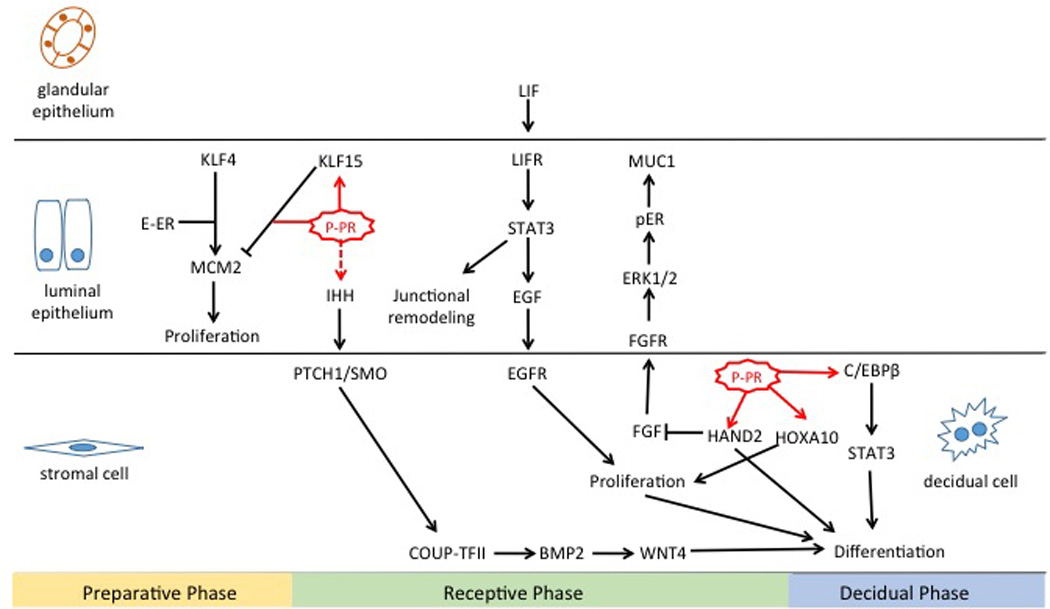

While these mouse models established an essential role of PR signaling in the uterus during early pregnancy, it was important to decipher the molecular pathways regulated by this receptor during the pre- and post-implantation phases. The advent of global gene expression analyses, using DNA microarrays, allowed the delineation of these pathways. Employing the well-known PR antagonist RU486, Cheon et al.,17 identified a large repertoire of PR-regulated genes that control uterine function during implantation. The DeMayo group also identified a number of genes induced in the uterine tissue upon acute and chronic P administration in non-pregnant ovariectomized mice.18 Collectively, these studies revealed that P-dependent pathways play critical roles in modulating the functions of both uterine epithelial and stromal cells to establish an environment necessary for successful establishment of pregnancy. In this review, we highlight the cross-talk between the factors that function downstream of PR to (1) control epithelial proliferation necessary for the acquisition of uterine receptivity and (2) stimulate stromal cell differentiation necessary for the establishment of pregnancy (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A schematic diagram highlighting the cross-talk between PR-regulated factors in endometrial epithelium and stroma.

Factors that function downstream of PR to control epithelial receptivity and stromal cell differentiation are shown.

Control of Uterine Receptivity by PR-Regulated Epithelial Factors

Indian hedgehog (IHH)

Two independent studies reported that IHH, a member of the hedgehog gene family, is a P-regulated factor expressed in uterine epithelium at the time of implantation.19, 20 This observation was later substantiated by the identification of a P response element in the proximal promoter region of the Ihh gene to which the PR binds upon P stimulation.21 Spatiotemporal analysis of IHH expression revealed that it is localized in the uterine luminal and glandular epithelia starting on day 2 of pregnancy when P levels rise in the preimplantation phase.20 The IHH expression peaks on day 3 and decreases by days 4–5. It is known that binding of IHH to the transmembrane Patched receptor (Ptc) triggers recruitment and activation of the intracellular transducer Smoothened.22 These signaling events activate the downstream transcription factors Gli and chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor II (COUP-TFII), which regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Following the induction of IHH in the preimplantation uterus, the expression of Ptc and the COUP-TFII is elevated in uterine stromal cells.19, 20 These findings support the concept that epithelial-derived IHH controls stromal functions via paracrine mechanisms. Tissue recombination experiments, using epithelium and stroma isolated from wild-type and PRKO mice, revealed that stromal PR is required for epithelial expression of Ihh and stromal expression of Ptc and COUP-TFII.23 Later, Franco et al.,21 using a uterine epithelial-specific PR knockout mouse model, reported reduced expression of Ihh with the loss of epithelial PR. These results suggested that epithelial PR may also play a role in IHH expression during pregnancy. Interestingly, recent studies have shown that loss of LIF signaling in uteri of Lif-null mice and uteri of mice lacking epithelial Stat3 is associated with reduced Ihh expression.7, 24, 25 These results are consistent with the observation that P and LIF act synergistically to induce Ihh expression in the uterus.26

Conditional deletion of Ihh in the uterus resulted in infertility due to a defect in embryo implantation.27 In mice lacking uterine Ihh, termed Ihhd/d, the epithelium failed to attain the receptive state. Microarray analysis of Ihh-null uteri revealed upregulation of several E-regulated genes, including mucin 1 (Muc1), lactotransferrin (Ltf), and wingless-type MMTV integration site (WNT) family member 4 (Wnt4), suggesting that IHH may be involved in modulating estrogen receptor (ER) activity during the peri-implantation period.28 Similar to Ihhd/d mice, those harboring uterine deletion of COUP-TFII also showed increased expression of epithelial ERα and its targets, such as Ltf and Muc1, resulting in compromised uterine receptivity and implantation failure.27, 29 The PR-IHH-COUP-TFII axis, therefore, plays an important role during implantation by controlling epithelial function.

Further studies revealed that the loss of Ihh in the uterine epithelium is also associated with aberrant gene expression in the stroma, indicating that IHH regulates stromal function via paracrine mechanisms.29 Ihhd/d mice failed to initiate the P-induced stromal cell proliferation that occurs prior to decidualization in the peri-implantation phase.27 The cell cycle regulatory factor CCND1 and the minichromosome maintenance family member MCM3, which are critical for stromal cell proliferation, were undetectable in Ihh-null uteri.28 Further investigation revealed that deletion of Ihh downregulates epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression in the stromal cells, identifying it as yet another downstream target of the IHH signaling pathway. Microarray analysis identified additional members of the EGF receptor family that are regulated by IHH, including Erbb2/Her2, Erbb3/Her3, and Erbb4/Her4.28 These results raised the possibility that IHH, by controlling downstream EGF-EGFR signaling, acts as a critical driver of stromal proliferation and differentiation. Thus, P-induced IHH triggers multiple signaling pathways in epithelial and stromal compartments to control uterine receptivity and decidualization during implantation.

Kruppel-like factor 15 (KLF15) and Minichromosome Maintenance protein 2 (MCM2)

Pollard’s group performed microarray analysis of E- and P-primed mouse uterine epithelial cells to show differential expression of KLF4 and KLF15, which belong to the Kruppel-like (KLF) family of transcription factors.30 KLF4 was expressed in the uterine epithelium of ovariectomized mice upon treatment with E alone while KLF15 was induced in response to treatment of P-primed uterus with E. Interestingly, a recent ChIP-sequencing study showed that the KLF15 gene harbors PR binding sites, suggesting that it is a direct target of PR.14

Studies using both in vivo and in vitro approaches presented a plausible mechanism by which PR-driven KLF15 may control epithelial proliferation.31 According to this hypothesis, in response to E, uterine epithelium expresses KLF4, which stimulates synthesis of the minichromosome maintenance (MCM)-2 protein. MCM2 is an essential component of the hexameric MCM2–7 complex that is required for initiation of DNA synthesis.32 As P levels increase, KLF15 is induced, which then promotes a rapid decline in the level of MCM2. ChIP analysis suggested that P disrupts the transcription complex consisting of KLF4, ER and RNA polymerase II and favors the assembly of a PR-KLF15 complex at the Mcm2 promoter. However, KLF15 is unable to recruit RNA polymerase II efficiently, thereby reducing the cellular levels of MCM2. Down regulation of the MCM2 proteins results in inhibition of DNA synthesis and cessation of cell proliferation. Collectively, these results suggest that E-induced KLF4 stimulates DNA replication during cell division, while P-induced KLF15 inhibits this process.31

Control of Uterine Receptivity and Decidualization by PR-Regulated Stromal Factors

Heart and neural crest derivatives-expressed 2 (HAND2)

Li et al discovered that treatment of mice with RU486, which blocked implantation, also abolished the expression of HAND2, a transcription factor expressed in mouse uterine stromal cells.33 When Hand2 gene was deleted in the uterine stroma in a conditional knockout mouse model (Hand2d/d), the luminal epithelium failed to acquire competency for embryo implantation. Thus, HAND2 induced by PR in stromal cells is essential for epithelial receptivity.33 Gene expression profiling of uterine stromal cells isolated from Hand2d/d mice on day 4 of pregnancy, revealed that the expression of transcripts corresponding to several members of the fibroblast growth factor family (FGFs), namely Fgf1, Fgf2, Fgf9, and Fgf18, is increased in uterine stroma of Hand2d/d mice. These results suggested that, during the receptive phase, HAND2 inhibits expression of the stromal FGFs, Fgf-1, -2, -9, and -18, which act via FGF receptor (FGFR) to activate the extracellular-signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) that control epithelial proliferation. Further investigation showed that persistent activation of the FGFR-ERK1/2 pathway in Hand2d/d uteri is also responsible for activation of ERα in epithelial cells leading to increased estrogenic activity, a condition unfavorable for uterine receptivity and embryo implantation.33 Interestingly, the stromal expression of HAND2 continues beyond the receptive phase (day 4) into the decidual phase (days 5–7) of pregnancy. It was reported that attenuation of HAND2 transcripts by siRNAs in HESC results in compromised decidualization.34 Therefore, HAND2, besides its role in controlling epithelial receptivity, also plays a crucial role during stromal decidualization, although the mechanisms by which HAND2 controls this process remain unknown.

Bone Morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) and WNT4

The bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2), a member of the TGF-β superfamily, is a P-regulated gene critical for implantation and decidualization.35, 36 Decidual stage-specific expression of BMP2 and its receptor in the uterine stromal cells during early pregnancy indicated a functional link between BMP2 signaling and the P-dependent changes underlying stromal differentiation during decidualization.35 It was demonstrated that addition of recombinant BMP2 to undifferentiated mouse or human endometrial stromal cultures markedly advanced the differentiation program by stimulating the Smad signaling pathway.35 Conversely, siRNA-mediated down-regulation of BMP2 expression in these cells efficiently blocked the differentiation process. Consistent with these in vitro findings, conditional disruption of the BMP2 gene in the uterus led to female infertility primarily due to a failure of decidualization.36

WNT4 was identified as a specific downstream target of uterine BMP2 signaling.35, 37 A robust induction of Wnt 4 transcripts was seen in the primary mouse endometrial stromal cultures when BMP2 was added to induce differentiation. These findings, along with the overlapping expression of BMP2 and WNT4 proteins in mouse uterine stromal compartment during in vivo decidualization, further strengthened the view that BMP2 acts via its downstream target WNT4 to critically regulate endometrial stromal differentiation. Consistent with this view, conditional loss of Wnt4 in mouse uterus exhibited impaired decidualization and implantation failure.38 BMP2 and WNT4 are also strongly induced in human endometrial stromal cells during decidualization.35 ChIP-sequencing analysis revealed that BMP2 gene is potentially directly regulated by both PR-A and PR-B.13 siRNA-mediated blockade of their expression in these cells showed that both BMP2 and WNT4 are critical for this differentiation process.37 Collectively, these results established that the BMP2-WNT4 pathway, acting downstream of PR signaling, has critical, conserved functions during decidualization.

Homeobox gene HOXA10

The Abdominal B-like homeobox gene, HOXA10, is expressed in a PR-dependent manner in uterine stromal cells during decidualization.39 HOXA10 is involved in the development of genitourinary and adult female reproductive tract. Null mutation of Hoxa10 resulted in a severe defect in decidualization and female infertility.40 The expression of FKBP52, a co-chaperone involved in assembly of steroid receptors, is altered in the HOXA10-deficient mouse (Hoxa10d/d) uterus, which contributes to the implantation and decidualization defect.41 HOXA10 is also induced in human endometrial stromal cells in response to P.42 A recent genomic study using these cells identified P response element in the HOXA10 gene promoter, implying that HOXA10 is a direct target of PR in endometrial stromal cells.14 Interestingly, it has been reported recently that FoxM1 functions downstream of Hoxa10 to control stromal cell proliferation in the mouse 43 and it directs the expression of STAT3 during human endometrial stromal cell differentiation.44

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ)

The transcription factor C/EBPβ is induced at the implantation sites in mouse, baboon and human endometrium.45, 46 Both E and P regulate expression of C/EBPβ. While E regulates the expression of C/EBPβ in uterine epithelium, P promotes its expression in the stroma.45 Previous studies,45 employing a global knockout of C/EBPβ, established a critical role of this factor in the regulation of uterine function during early pregnancy. It was reported that BMP signaling through the BMP type 1 receptor regulates C/EBPβ and, subsequently, PR expression during decidualization.47 C/EBPβ regulates uterine epithelial proliferation and apoptosis as well as stromal cell proliferation and differentiation, the absence of which leads to a complete failure of the implantation process and a steroid unresponsive uterus. Stromal proliferation is blocked at G2 to M transition in C/EBPβ-null uteri.48 In human endometrial stromal cells, C/EBPβ controls proliferation and differentiation by regulating cyclin E-cdk2 and STAT3.49 Interestingly, recent genomic studies in these cells showed that PR interacts with C/EBPβ at the P-regulated region of AURKA, which encodes the aurora kinase A.13 This kinase is involved in microtubule formation and/or stabilization at the spindle pole during cell division. These results are consistent with the view that C/EBPβ and PR act in concert to regulate human endometrial proliferation and differentiation.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)

STAT3, although not a direct target of P regulation, is an important collaborator of P signaling during early pregnancy. It is a direct downstream target of regulation by C/EBPβ and a well-known mediator of LIF signaling in the uterus.49, 50 Binding of LIF to its receptor activates JAK kinases, which phosphorylate STAT3. Phosphorylated STAT3 translocates to the cell nucleus and regulates transcription of target genes.51 Mouse models with conditional ablation of Stat3 in both epithelial and stromal cells established the critical role played by STAT3 in implantation.7, 25, 52 In the nucleus, STAT3 regulates expression of PR target genes, including Hoxa10 in the stromal cells and Ihh in the epithelial cells.7, 25, 52 While the precise mechanism by which PR and STAT3 interact to regulate gene expression remains unclear, a recent study suggested that PR interacts directly with STAT3 to modulate gene expression at the time of implantation.52 Interestingly, a significant enrichment of STAT3 binding motifs adjacent to several PR-B binding sites was seen in the genome of human endometrial stromal cells during decidualization.13 Collectively, these findings support the concept that coordinated interactions involving PR and STAT3 are critical for regulation of a subset of P responsive genes during decidualization.

Insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2)

Growing evidence suggests that the regulation of energy metabolism is essential for the establishment of successful pregnancy.53 It was recently reported that (IRS2), a key mediator for the downstream signaling pathways of both insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1, acts downstream of PR signaling to regulate decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells.13 Silencing of PR in these cells led to a down regulation of IRS2 transcripts, identifying it as a target of PR. ChIP-sequencing analysis confirmed that IRS2 is potentially regulated by both PR-A and PR-B.13 Aberrant IRS2 signaling has been implicated in reproductive disorders associated with insulin metabolism.53, 54 It is conceivable that IRS2 is a critical link between PR signaling and energy metabolism during stromal differentiation. P-induced IRS2 may be involved in localization of glucose transporters to the cell membrane to enable the endometrial stromal cells to take up enough glucose to meet the increased energy needs during their proliferation and differentiation. IRS2 may also be involved in the regulation of genes controlling glucose metabolism.55

Control of Uterine Angiogenesis and Immune Response by PR: Emerging Areas of Interest

New evidence emerging from ChIP-sequencing and gene expression profiling analyses indicates that PR-B is a critical regulator of uterine angiogenesis, an essential feature of normal endometrial development and placentation. Angiogenesis-related genes found downstream of PR-B included vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), angiopoietin 2 (ANGPT2), angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2). Previous reports indicated that P regulates VEGFA, a key angiogenic factor in human endometrium.56 Consistent with this report, Kaya et al.,13 identified several PR binding sites within a ± 200 kb window of the transcription start site of the VEGF gene, leading to the concept that these regions might be bound by PR-B, which then regulates VEGFA expression through a looping mechanism. ANGPT2, ANGPTL4 and FGF2 also contained consensus PR binding sites, suggesting direct regulation by PR. Future research will address how diverse angiogenic factors regulated by PR work in concert to facilitate proper endometrial neoangiogenesis to support the implanted embryo.

Maternal immune tolerance of the semiallogeneic embryo requires a delicate local modulation of immune response within the pregnant uterus during implantation. P is known to play an important role in this immuno-modulation, although the mechanisms of its action remain unclear.57 P exerts an anti-inflammatory effect during implantation by suppressing E-induced influx of neutrophils and macrophages into the stroma. The PRKO mice exhibit an increased number of neutrophils traversing the uterine epithelium into the lumen, causing increased inflammation and edema.58 It has been proposed that HOXA10 may mediate the immunomodulatory effects of P. This was based on the observation that HOXA10-deficiency is associated with severe immunological dysregulation during implantation.59 Mice lacking Hoxa10 exhibit abnormal polyclonal expansion of T-lymphocytes compared to wild type mice.59 P is also reported to suppress the proinflammatory responses of uterine dendritic cells, which play a crucial role in implantation.60 Treatment with RU486 prevented this P-mediated suppression of proinflammatory cytokines produced by dendritic cells.61 Further studies are needed to delineate the PR-regulated pathways that modulate the innate immune system at the implantation site to ensure survival of the embryo.

Conclusion

Development of genetically engineered mouse models lacking PR and its target genes has provided a wealth of information regarding the roles of P-regulated pathways in endometrial receptivity and implantation. The identification of genome-wide binding sites and downstream gene networks of PR during endometrial differentiation have offered unique insights into the role of this receptor in human uterine biology. These studies have revealed that several P-regulated pathways involved in endometrial function during implantation are conserved in mice and humans. Dysregulated P signaling has been implicated not only in recurrent miscarriage and infertility, but also in other reproductive pathologies, such as endometriosis and endometrial cancer. Endometriosis, a prevalent gynecological disease, is considered a P resistant disease, although the mechanism of this resistance is not fully understood.62 Similarly, endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer are associated with compromised P signaling that fails to oppose E signaling.63 Undoubtedly, further studies, involving a comprehensive mouse to human translational approach, will provide important mechanistic insights regarding the role of P-regulated factors in the context of endometrial dysfunctions associated with infertility, endometriosis and endometrial cancer.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD/NIH grant U54 HD055787 as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research and R21 HD078983.

References

- 1.Carson DD, Bagchi I, Dey SK, Enders AC, Fazleabas AT, Lessey BA, Yoshinaga K. Embryo implantation. Dev Biol. 2000;223:217–237. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazer FW, Spencer TE, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC. Uterine receptivity to implantation of blastocysts in mammals. Frontiers in bioscience (Scholar edition) 2011;3:745–767. doi: 10.2741/s184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dey SK, Lim H, Das SK, Reese J, Paria BC, Daikoku T, Wang H. Molecular cues to implantation. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:341–373. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pawar S, Hantak AM, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. Minireview: Steroid-regulated paracrine mechanisms controlling implantation. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:1408–1422. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramathal CY, Bagchi IC, Taylor RN, Bagchi MK. Endometrial decidualization: of mice and men. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28:17–26. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cha J, Sun X, Dey SK. Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat Med. 2012;18:1754–1767. doi: 10.1038/nm.3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pawar S, Starosvetsky E, Orvis GD, Behringer RR, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. STAT3 regulates uterine epithelial remodeling and epithelial-stromal crosstalk during implantation. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:1996–2012. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh H, Aplin JD. Adhesion molecules in endometrial epithelium: tissue integrity and embryo implantation. J Anat. 2009;215:3–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.01034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conneely OM, Lydon JP. Progesterone receptors in reproduction: functional impact of the A and B isoforms. Steroids. 2000;65:571–577. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribeiro RC, Kushner PJ, Baxter JD. The nuclear hormone receptor gene superfamily. Annual review of medicine. 1995;46:443–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annual review of biochemistry. 1994;63:451–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lonard DM, O'Malley BW. The expanding cosmos of nuclear receptor coactivators. Cell. 2006;125:411–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaya HS, Hantak AM, Stubbs LJ, Taylor RN, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. Roles of progesterone receptor A and B isoforms during human endometrial decidualization. Mol Endocrinol. 2015;29:882–895. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazur EC, Vasquez YM, Li X, Kommagani R, Jiang L, Chen R, Lanz RB, Kovanci E, Gibbons WE, DeMayo FJ. Progesterone receptor transcriptome and cistrome in decidualized human endometrial stromal cells. Endocrinology. 2015;156:2239–2253. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR, Mani SK, Hughes AR, Montgomery CA, Jr, Shyamala G, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes & development. 1995;9:2266–2278. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conneely OM, Mulac-Jericevic B, Lydon JP, De Mayo FJ. Reproductive functions of the progesterone receptor isoforms: lessons from knock-out mice. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2001;179:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00465-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheon YP, Li Q, Xu X, DeMayo FJ, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. A genomic approach to identify novel progesterone receptor regulated pathways in the uterus during implantation. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2853–2871. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeong JW, Lee KY, Kwak I, White LD, Hilsenbeck SG, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ. Identification of murine uterine genes regulated in a ligand-dependent manner by the progesterone receptor. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3490–3505. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto H, Zhao X, Das SK, Hogan BL, Dey SK. Indian hedgehog as a progesterone-responsive factor mediating epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the mouse uterus. Dev Biol. 2002;245:280–290. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takamoto N, Zhao B, Tsai SY, DeMayo FJ. Identification of Indian hedgehog as a progesterone-responsive gene in the murine uterus. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2338–2348. doi: 10.1210/me.2001-0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franco HL, Rubel CA, Large MJ, Wetendorf M, Fernandez-Valdivia R, Jeong JW, Spencer TE, Behringer RR, Lydon JP, Demayo FJ. Epithelial progesterone receptor exhibits pleiotropic roles in uterine development and function. FASEB J. 2012;26:1218–1227. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-193334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMahon AP. More surprises in the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Cell. 2000;100:185–188. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon L, Spiewak KA, Ekman GC, Kim J, Lydon JP, Bagchi MK, Bagchi IC, DeMayo FJ, Cooke PS. Stromal progesterone receptors mediate induction of Indian Hedgehog (IHH) in uterine epithelium and its downstream targets in uterine stroma. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3871–3876. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakitani S, Hondo E, Phichitraslip T, Stewart CL, Kiso Y. Upregulation of Indian hedgehog gene in the uterine epithelium by leukemia inhibitory factor during mouse implantation. The Journal of reproduction and development. 2008;54:113–116. doi: 10.1262/jrd.19120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun X, Bartos A, Whitsett JA, Dey SK. Uterine deletion of Gp130 or Stat3 shows implantation failure with increased estrogenic responses. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:1492–1501. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawar S, Laws MJ, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. Uterine Epithelial Estrogen Receptor-alpha Controls Decidualization via a Paracrine Mechanism. Mol Endocrinol. 2015;29:1362–1374. doi: 10.1210/me.2015-1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee K, Jeong J, Kwak I, Yu CT, Lanske B, Soegiarto DW, Toftgard R, Tsai MJ, Tsai S, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ. Indian hedgehog is a major mediator of progesterone signaling in the mouse uterus. Nature genetics. 2006;38:1204–1209. doi: 10.1038/ng1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franco HL, Lee KY, Broaddus RR, White LD, Lanske B, Lydon JP, Jeong JW, DeMayo FJ. Ablation of Indian hedgehog in the murine uterus results in decreased cell cycle progression, aberrant epidermal growth factor signaling, and increased estrogen signaling. Biology of reproduction. 2010;82:783–790. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.080259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurihara I, Lee DK, Petit FG, Jeong J, Lee K, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Tsai MJ, Tsai SY. COUP-TFII mediates progesterone regulation of uterine implantation by controlling ER activity. PLoS genetics. 2007;3:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan H, Zhu L, Deng Y, Pollard JW. Microarray analysis of uterine epithelial gene expression during the implantation window in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4904–4916. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ray S, Pollard JW. KLF15 negatively regulates estrogen-induced epithelial cell proliferation by inhibition of DNA replication licensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1334–E1343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118515109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tye BK. Minichromosome maintenance as a genetic assay for defects in DNA replication. Methods (San Diego, Calif) 1999;18:329–334. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Q, Kannan A, DeMayo FJ, Lydon JP, Cooke PS, Yamagishi H, Srivastava D, Bagchi MK, Bagchi IC. The antiproliferative action of progesterone in uterine epithelium is mediated by Hand2. Science. 2011;331:912–916. doi: 10.1126/science.1197454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huyen DV, Bany BM. Evidence for a conserved function of heart and neural crest derivatives expressed transcript 2 in mouse and human decidualization. Reproduction. 2011;142:353–368. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Q, Kannan A, Wang W, Demayo FJ, Taylor RN, Bagchi MK, Bagchi IC. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 functions via a conserved signaling pathway involving Wnt4 to regulate uterine decidualization in the mouse and the human. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:31725–31732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704723200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee KY, Jeong JW, Wang J, Ma L, Martin JF, Tsai SY, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ. Bmp2 is critical for the murine uterine decidual response. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:5468–5478. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00342-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q, Kannan A, Das A, Demayo FJ, Hornsby PJ, Young SL, Taylor RN, Bagchi MK, Bagchi IC. WNT4 acts downstream of BMP2 and functions via beta-catenin signaling pathway to regulate human endometrial stromal cell differentiation. Endocrinology. 2013;154:446–457. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franco HL, Dai D, Lee KY, Rubel CA, Roop D, Boerboom D, Jeong JW, Lydon JP, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK, DeMayo FJ. WNT4 is a key regulator of normal postnatal uterine development and progesterone signaling during embryo implantation and decidualization in the mouse. FASEB J. 2011;25:1176–1187. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-175349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim H, Ma L, Ma WG, Maas RL, Dey SK. Hoxa-10 regulates uterine stromal cell responsiveness to progesterone during implantation and decidualization in the mouse. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1005–1017. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.6.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benson GV, Lim H, Paria BC, Satokata I, Dey SK, Maas RL. Mechanisms of reduced fertility in Hoxa-10 mutant mice: uterine homeosis and loss of maternal Hoxa-10 expression. Development (Cambridge, England) 1996;122:2687–2696. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daikoku T, Tranguch S, Friedman DB, Das SK, Smith DF, Dey SK. Proteomic analysis identifies immunophilin FK506 binding protein 4 (FKBP52) as a downstream target of Hoxa10 in the periimplantation mouse uterus. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:683–697. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor HS, Arici A, Olive D, Igarashi P. HOXA10 is expressed in response to sex steroids at the time of implantation in the human endometrium. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;101:1379–1384. doi: 10.1172/JCI1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao F, Bian F, Ma X, Kalinichenko VV, Das SK. Control of regional decidualization in implantation: Role of FoxM1 downstream of Hoxa10 and cyclin D3. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13863. doi: 10.1038/srep13863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang Y, Liao Y, He H, Xin Q, Tu Z, Kong S, Cui T, Wang B, Quan S, Li B, Zhang S, Wang H. FoxM1 Directs STAT3 Expression Essential for Human Endometrial Stromal Decidualization. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13735. doi: 10.1038/srep13735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mantena SR, Kannan A, Cheon YP, Li Q, Johnson PF, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. C/EBPbeta is a critical mediator of steroid hormone-regulated cell proliferation and differentiation in the uterine epithelium and stroma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1870–1875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507261103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kannan A, Fazleabas AT, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. The transcription factor C/EBPbeta is a marker of uterine receptivity and expressed at the implantation site in the primate. Reproductive sciences (Thousand Oaks, Calif) 2010;17:434–443. doi: 10.1177/1933719110361384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clementi C, Tripurani SK, Large MJ, Edson MA, Creighton CJ, Hawkins SM, Kovanci E, Kaartinen V, Lydon JP, Pangas SA, DeMayo FJ, Matzuk MM. Activin-like kinase 2 functions in peri-implantation uterine signaling in mice and humans. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang W, Li Q, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. The CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta is a critical regulator of steroid-induced mitotic expansion of uterine stromal cells during decidualization. Endocrinology. 2010;151:3929–3940. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang W, Taylor RN, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. Regulation of human endometrial stromal proliferation and differentiation by C/EBPbeta involves cyclin E-cdk2 and STAT3. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:2016–2030. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng JG, Chen JR, Hernandez L, Alvord WG, Stewart CL. Dual control of LIF expression and LIF receptor function regulate Stat3 activation at the onset of uterine receptivity and embryo implantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8680–8685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151180898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levy DE, Lee CK. What does Stat3 do? The Journal of clinical investigation. 2002;109:1143–1148. doi: 10.1172/JCI15650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JH, Kim TH, Oh SJ, Yoo JY, Akira S, Ku BJ, Lydon JP, Jeong JW. Signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (Stat3) plays a critical role in implantation via progesterone receptor in uterus. FASEB J. 2013;27:2553–2563. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-225664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frolova AI, Moley KH. Glucose transporters in the uterus: an analysis of tissue distribution and proposed physiological roles. Reproduction. 2011;142:211–220. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ganeff C, Chatel G, Munaut C, Frankenne F, Foidart JM, Winkler R. The IGF system in in-vitro human decidualization. Molecular human reproduction. 2009;15:27–38. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gan073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roncero I, Alvarez E, Acosta C, Sanz C, Barrio P, Hurtado-Carneiro V, Burks D, Blazquez E. Insulin-receptor substrate-2 (irs-2) is required for maintaining glucokinase and glucokinase regulatory protein expression in mouse liver. PloS one. 2013;8:e58797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ancelin M, Buteau-Lozano H, Meduri G, Osborne-Pellegrin M, Sordello S, Plouet J, Perrot-Applanat M. A dynamic shift of VEGF isoforms with a transient and selective progesterone-induced expression of VEGF189 regulates angiogenesis and vascular permeability in human uterus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6023–6028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082110999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kachkache M, Acker GM, Chaouat G, Noun A, Garabedian M. Hormonal and local factors control the immunohistochemical distribution of immunocytes in the rat uterus before conceptus implantation: effects of ovariectomy, fallopian tube section, and injection. Biology of reproduction. 1991;45:860–868. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod45.6.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tibbetts TA, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW. Progesterone via its receptor antagonizes the pro-inflammatory activity of estrogen in the mouse uterus. Biology of reproduction. 1999;60:1158–1165. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.5.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yao MW, Lim H, Schust DJ, Choe SE, Farago A, Ding Y, Michaud S, Church GM, Maas RL. Gene expression profiling reveals progesterone-mediated cell cycle and immunoregulatory roles of Hoxa-10 in the preimplantation uterus. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:610–627. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plaks V, Birnberg T, Berkutzki T, Sela S, BenYashar A, Kalchenko V, Mor G, Keshet E, Dekel N, Neeman M, Jung S. Uterine DCs are crucial for decidua formation during embryo implantation in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:3954–3965. doi: 10.1172/JCI36682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Butts CL, Shukair SA, Duncan KM, Bowers E, Horn C, Belyavskaya E, Tonelli L, Sternberg EM. Progesterone inhibits mature rat dendritic cells in a receptor-mediated fashion. International immunology. 2007;19:287–296. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kao LC, Germeyer A, Tulac S, Lobo S, Yang JP, Taylor RN, Osteen K, Lessey BA, Giudice LC. Expression profiling of endometrium from women with endometriosis reveals candidate genes for disease-based implantation failure and infertility. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2870–2881. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jeong JW, Lee HS, Lee KY, White LD, Broaddus RR, Zhang YW, Vande Woude GF, Giudice LC, Young SL, Lessey BA, Tsai SY, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ. Mig-6 modulates uterine steroid hormone responsiveness and exhibits altered expression in endometrial disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8677–8682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903632106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]