Abstract

Background/Aims

Mucosal healing (MH) is a proposed therapeutic goal for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). Whether MH is the final goal for UC, however, remains under debate. Therefore, to elucidate clinical variables predicting relapse after MH in UC could be useful for establishing further therapeutic strategy. The aim of this study is to evaluate the predictive variables for relapse in UC-patients after achieving MH.

Methods

From April 2010 to February 2015, 298 UC-patients treated at Kitano Hospital were retrospectively analyzed. MH was defined as Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 or 1. The cumulative relapse free rate after achieving MH was evaluated. Predictive variables for relapse in UC-patients were assessed by Cox regression analysis.

Results

Of 298 UC-patients, 88 (29.5%) achieved MH. Of the 88 UC patients who achieved MH, 21 (23.9%) experienced UC-relapse. Based on Kaplan-Meier analysis, the cumulative relapse free rate at 1, 3, and 5 years after achieving MH was 87.9%, 70.2%, and 63.8%, respectively. The cumulative relapse free rate tended to be higher in the Mayo-0 group (76.9%) than in the Mayo-1 group (54.1%) at 5 years, although the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.313). Cox regression analysis indicated that the use of an immunomodulator was a predictive variable for relapse in UC-patients after achieving MH (P=0.035).

Conclusions

Our data demonstrated that the prognosis of UC patients after achieving endoscopic MH could be based on UC refractoriness requiring an immunomodulator.

Keywords: Colitis, ulcerative; Mucosal healing; Endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic relapsing inflammatory disorder characterized by colonic inflammation.1 5-Aminosalicylate and corticosteroids are conventionally used for treatment of UC.2,3,4 Recently, several papers reported that calcineurin inhibitors and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antagonists are effective treatments for patients with UC refractory to corticosteroids.5,6 Particularly, randomized controlled studies demonstrated that, in moderate to severe UC patients, TNF-α antagonists were effective not only for induction and maintenance of remission, but also for achieving endoscopic mucosal healing (MH).5 Moreover, these trials revealed that achieving endoscopic MH would be a predictive variable of better long-term clinical outcome because of a lower risk of colectomy in UC patients with endoscopic MH.7 As a result, not only induction of clinical remission, but also achieving endoscopic MH is proposed as the new therapeutic goal for treatment of UC. In clinical practice, however, relapse of UC was found in UC patients despite achieving endoscopic MH. A resent paper also reported that the cumulative relapse rate at 5 years after achieving endoscopic MH was 22% of UC patients.8 According to those data, it remained controversial whether or not endoscopic MH is the final goal of treatment of UC, because clinical relapse is not infrequent even in patients achieving endoscopic MH. Therefore, identifying the clinical variables predicting relapse in UC patients after achieving endoscopic MH would be important for establishing the optimal therapeutic strategy for maintenance of clinical remission and MH. Hence, the aim of this study was to elucidate the clinical variables predicting relapse in UC patients after achieving endoscopic MH.

METHODS

1. Patients

From April 2010 to February 2015, 298 patients with UC who had been treated at Kitano Hospital were retrospectively analyzed. The diagnosis of UC was confirmed by endoscopic and pathologic findings. This retrospective, observational, single-center study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Kitano Hospital.

2. Evaluation of Clinical and Endoscopic Activity of UC

Clinical and endoscopic activities were evaluated with the Lichtiger index and Mayo score, respectively. Clinical remission was defined as a Lichtiger index of less than 4 under corticosteroid- and granulocyte monocyte adsorption apheresis-free conditions. The relapse of UC was defined as any recurrence of UC-related symptoms that required additional treatment.9 Endoscopic MH was defined as Mayo score of 0 or 1. Patients were categorized into two groups (MH group and non-MH group) based on their endoscopic score after completely tapering corticosteroids, and the MH group was included in our analysis.

3. Definitions

Corticosteroid-refractoriness was defined as no improvement in disease activity of UC despite treatment with corticosteroids.10,11 Corticosteroid-dependency was defined as disability to discontinue corticosteroids due to a relapse of UC within corticosteroid-tapering or 3 months of stopping the corticosteroid treatment.10,11

4. Assessment and Statistics

The primary outcome was the cumulative relapse free rate in UC patients after achieving MH. The secondary outcome included the identification of clinical variables associated with the risk of relapse in UC patients after achieving MH. Categorical and continuous data were compared using a two-tailed Fisher exact test, chi-square test and Mann-Whitney U test. The cumulative relapse free rate was evaluated by Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test. To perform multivariate analysis of the time to relapse in UC patient after achieving MH, clinical variables were analyzed by Cox regression. The clinical variables that were suggested to be important variables associated with relapse by univariate analysis were selected for multivariate analysis. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Patient's Characteristics

A total 88 of 298 UC patients (29.5%) were found to have endoscopic MH. The characteristics of the 88 patients with UC are shown in Table 1. The median duration of follow-up of the 88 patients was 1.33 years (range, 0.02–7.50). Forty-five of the 88 patients (51.1%) were male and the remaining 43 (48.9%) were female. The median age at diagnosis of UC was 34-years old (range, 10–75 years). Thirty-two of the 88 patients (36.4%) had extensive colitis type, 21 (23.9%) had left-sided type, and 34 (38.6%) had proctitis type of UC. Forty-three of the 88 patients (48.9%) with UC was defined as Mayo-0, and the remaining 45 patients (51.1%) were defined as Mayo-1. Seventy-two patients (81.8%) with UC were treated with 5-aminosalicylate for maintenance therapy, 12 (13.6%) were treated with azathiopurine/6-mercaptopurine, 1 (1.1%) with granulocyte monocyte adsorption apheresis, 6 (6.8%) with TNF-α antagonists, and 8 (9.1%) were not treated. Twenty-three of the 88 patients (26.1%) with UC had a history of treatment with corticosteroid, and 4 patients (4.5%) were defined as having corticosteroid-refractory UC and 6 (6.8%) were defined as having corticosteroid-dependent UC.

Table 1. Patient's Characteristics.

| Variable | n=88 |

|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 45/43 |

| Age at diagnosis (yr) (Median) | 34 (10–75) |

| Extent of disease | |

| Extensive colitis | 32 (36.4) |

| Left-sided | 21 (23.9) |

| Proctitis | 34 (38.6) |

| Unclear | 1 (1.1) |

| Endoscopic Mayo score | |

| Mayo-0 | 43 (48.9) |

| Mayo-1 | 45 (51.1) |

| Maintenance therapy | |

| 5-ASA | 72 (81.8) |

| AZA/6MP | 12 (13.6) |

| GMAA | 1 (1.1) |

| TNF-α antagonists | 6 (6.8) |

| None | 8 (9.1) |

| History of treatment with corticosteroid | 23 (26.1) |

| Corticosteroid refractory | 4 (4.5) |

| Corticosteroid dependent | 6 (6.8) |

Values are presented as n (%).

M, male; F, female; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; AZA/6MP, Azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine; GMAA, granulocyte monocyte adsorption apheresis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

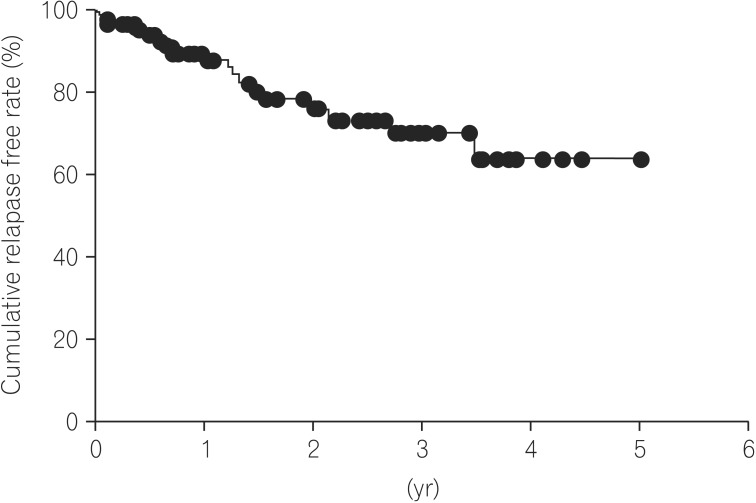

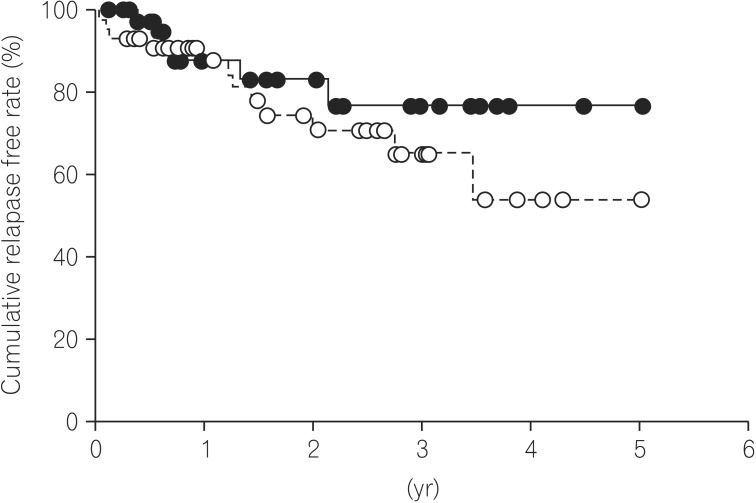

2. The Long-term Clinical Outcome of UC Patients after Achieving MH

In 21 of the 88 patients with endoscopic MH (23.9%), a relapse of UC occurred. The median time at relapse of UC was 1.2 years (range, 0.02–5.20) after achieving MH. Based on Kaplan-Meier analysis, the cumulative relapse free rate at 1, 3, and 5 years of UC patients after achieving MH were 87.9%, 70.2% and 63.8%, respectively (Fig. 1). We divided the 88 UC patients with endoscopic MH into two groups, the Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 group, and evaluated the differences in the clinical characteristics between the Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 group. The median duration of follow-up of the Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 group was 0.77 years and 1.54 years, respectively (P=0.233). However, there was no significant difference of clinical characteristics between the Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 group (Table 2). On the other hand, the cumulative relapse free-rate of the Mayo-0 group tended to be high compared to that of the Mayo-1 group (76.9% [Mayo-0] and 54.1% [Mayo-1] at 5 years, respectively), although there was no significant difference in the cumulative relapse free rate between the Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 group (P=0.313) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Cumulative relapse free rate of UC patients after achieving mucosal healing. Based on Kaplan-Meier analysis, the cumulative relapse free rate at 1, 3 and 5 years of UC patients after achieving mucosal healing were 87.9%, 70.2% and 63.8%, respectively.

Table 2. Patient's Characteristics Between Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 Group.

| Variable | Mayo-0 n=43 |

Mayo-1 n=45 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 23/20 | 22/23 | 0.666 |

| Age at diagnosis (yr), median (range) | 34 (15–75) | 34 (10–71) | 0.333 |

| Extent of disease | 0.361 | ||

| Extensive colitis | 17 (39.5) | 15 (33.3) | |

| Left-sided | 6 (14.0) | 15 (33.3) | |

| Proctitis | 19 (44.2) | 15 (33.3) | |

| Unclear | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Maintenance therapy | |||

| 5-ASA | 35 (81.4) | 37 (82.2) | 0.860 |

| AZA/6MP | 5 (11.6) | 7 (15.6) | 0.821 |

| GMAA | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | N/A |

| TNF-α antagonists | 1 (2.3) | 5 (11.1) | N/A |

| None | 5 (11.6) | 3 (6.7) | N/A |

| History of treatment with corticosteroid | 9 (20.9) | 14 (31.1) | 0.399 |

| Corticosteroid refractory | 2 (4.7) | 2 (4.4) | N/A |

| Corticosteroid dependent | 2 (4.7) | 4 (8.9) | N/A |

Values are presented as n (%).

Categorical and continuous data were compared using a two-tailed Fisher exact test, Chi-squared test and Mann-Whitney U test.

M, male; F, female; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; AZA/6MP, Azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine; GMAA, granulocyte monocyte adsorption apheresis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; N/A, not applicable.

Fig. 2. Cumulative relapse free rate between the Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 group. The cumulative relapse free rate of the Mayo-0 group was estimated as 76.9% at 5 years after achieving mucosal healing (solid line), and that of the Mayo-1 group was estimated as 54.1%. There was no significant difference of cumulative relapse free rate between the Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 group (P=0.313).

3. The Clinical Variable for Relapse in UC Patients after Achieving MH

To investigate the clinical variable for relapse in UC patients after achieving MH, we evaluated the differences in the clinical characteristics of UC patients between the relapse and non-relapse group. As shown in Table 3, the rates of extensive colitis, Mayo-1 and immunomodulator use in the relapse group were higher than those in the non-relapse group, although there was no significant difference (Extensive colitis, P=0.08; Mayo-1, P=0.167; Immunomodulator use, P=0.055). Moreover, Cox regression analysis demonstrated that immunomodulator use was a clinical variable for relapse in UC patients after achieving MH (hazard ratio, 6.134; 95% CI, 1.134–33.170; P=0.035) (Table 4).

Table 3. Patient's Characteristics Between Non-Relapse and Relapse Group.

| Variable | non-Relapse n=67 |

Relapse n=21 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 34/23 | 11/10 | 0.564 |

| Age at diagnosis (yr), median (range) | 33 (10–75) | 35 (15–71) | 0.169 |

| Extent of disease | 0.265 | ||

| Extensive colitis | 21 (31.3) | 11 (52.4) | |

| Left-sided | 15 (22.4) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Proctitis | 30 (44.8) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Unclear | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Endoscopic Mayo score | 0.167 | ||

| Mayo-0 | 36 (53.7) | 7 (33.3) | |

| Mayo-1 | 31 (46.3) | 14 (66.7) | |

| Maintenance therapy | |||

| 5-ASA | 53 (79.1) | 19 (90.5) | 0.338 |

| AZA/6MP | 6 (9.0) | 6 (28.6) | 0.055 |

| GMAA | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| TNF-α antagonist | 3 (4.5) | 3 (14.3) | 0.145 |

| None | 6 (9.0) | 2 (9.5) | 1.000 |

| History of treatment with corticosteroid | 17 (25.4) | 6 (28.6) | 0.995 |

| Corticosteroid refractory | 3 (4.5) | 1 (4.8) | 1.000 |

| Corticosteroid dependent | 4 (6.0) | 2 (9.5) | 0.626 |

Values are presented as n (%).

Categorical and continuous data were compared using a two-tailed Fisher exact test, Chi-squared test and Mann-Whitney U test.

M, male; F, female; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; AZA/6MP, Azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine; GMAA, granulocyte monocyte adsorption apheresis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Table 4. The Multivariate Analyze of the Time to Relapse in UC Patients after Achieving Endoscopic mucosal healing.

| Variable | HR | P-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extensive colitis | 1.647 | 0.343 | 0.587 | 4.621 |

| Mayo-1 | 1.687 | 0.279 | 0.654 | 4.353 |

| Immunomodulator use | 6.134 | 0.035 | 1.134 | 33.17 |

HR, hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

Our current study demonstrated that the cumulative relapse free rate at 5 years of UC patients after achieving endoscopic MH was 63.8%. Moreover, there was no significant difference in the cumulative relapse free rate between the Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 group. Regarding the predictive variable of relapse in UC patients with endoscopic MH, our multivariate analysis revealed that the immunomodulator use was a clinical variable. In UC patients, particularly those requiring immunomodulators, therefore, our data suggest that we should treat toward a higher goal than endoscopic MH, such as histological MH.

It has been well known that endoscopic MH relates to a better long-term clinical-outcome of UC patients.7,12 The post hoc analysis of Active Ulcerative Colitis Trials (ACT) 1 and 2 demonstrated that UC patients treated with infliximab who achieved endoscopic MH at week 8 had a lower colectomy rate than those without MH.7 A recent paper also reported that rapid achievement of endoscopic MH with treatment of tacrolimus was associated with a better remission maintenance time.13 Therefore, achieving endoscopic MH has been proposed as the new therapeutic goal for the treatment of UC. However, few papers have reported the long-term outcome of UC patients after achieving endoscopic MH. Previously, Yokoyama et al. reported that cumulative relapse free rates at 5 years of Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 were 78% and 40%, respectively.8 Moreover, there was a significant difference in the cumulative relapse rate among Mayo-0, -1, -2, and -3 groups although the number of enrolled patients was very small.8 On the other hand, Ikeya et al. also evaluated the cumulative relapse-free rate between Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 group, and reported that there was no significant difference in prognosis between Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 group.13 Our data also demonstrated that cumulative relapse free rate at 5 years of Mayo-0 was 76.9% as similar to previous data.8 In our data, however, there was no significant difference in the cumulative relapse free rate between Mayo-0 and Mayo-1 (P=0.313). Therefore, it remains controversial whether or not Mayo-1 should be definitely differentiated from Mayo-0 for assessment of endoscopic MH. In either case, endoscopic MH could not be the final goal, but just a milestone in treatment of UC, because the relapse of UC was found not only in the Mayo-1 group, but also in the Mayo-0 group.

Recently, Barreiro-de Acosta et al. reported that a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 1 would be an independent risk factor for relapse during the 6 months of follow-up time after achieving MH.14 On the other hand, our multivariate analysis revealed that immunomodulator use, but not endoscopic findings, was a predictive variable of relapse for 5 years of follow-up time in UC patient with endoscopic MH. According to those data, endoscopic findings would be associated with clinical relapse in the short-term duration after achieving MH. Regarding relapse over the long-term after achieving MH, however, UC refractoriness requiring immunomodulator for maintenance of remission and MH would contribute to the clinical course of UC patients. Despite achieving endoscopic MH, therefore, we should keep the maintenance treatment deliberately in UC patients who required the treatment with immunomodulator.

It remained unclear whether or not endoscopic MH could be the final goal for treatment of UC. Several papers had also proposed that endoscopic MH is not suitable for the final therapeutic-goal of UC.15,16,17 Confocal laser endomicroscopy demonstrated that the activity of UC, such as impaired crypt regeneration, persistent inflammation, distinct abnormalities in angioarchitecture, and increased vascular permeability, remained in endoscopically normal colonic-mucosa in patients with UC in remission.18 According to those data, endoscopic findings alone, even if Mayo-0, are not suitable for assessment of "complete" MH. Recently, therefore, new therapeutic criteria of complete MH defined as histological mucosal healing were proposed.18,19 Particularly, histological evaluation would play an important role in assessment of complete MH, because it is reported that persistent histological inflammation is associated with an increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and colectomy in UC patients.17 According to a recent paper by Bryant RV, et al., complete remission, defined as both endoscopic and histological remission, could be associated with long-term better outcome compared with endoscopic remission alone.19 However, neither endoscopic nor histological remission were perfect for the assessment of complete MH, because 43% of UC patients with both endoscopic and histological remission required corticosteroids, and 12% of those required hospitalization over the 6-year follow-up period.19 Therefore, establishment of new criteria for assessment of "complete" MH is needed.

In our study, there were several limitations including small sample size, single center study and retrospective study. Particularly, due to the retrospective study, poor adherence to maintenance therapy or superimposed infection such as Clostridium difficile and cytomegalovirus infections, which would be important variables related to a relapse of UC, could not be analyzed. Moreover, the timing for decision of endoscopic MH in each patient varied. In this regard, our data should be cautiously interpreted and further prospective studies are required with a larger number of enrolled patients.

In conclusion, our data demonstrated that the prognosis of UC patients after achieving endoscopic MH would be based on UC refractoriness requiring immunomodulators, although further studies would be necessary for clarifying the clinical implication of endoscopic- or histologic-MH and evaluating long-term prognostic variables in UC with MH.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research [25860532 to T.Y].

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(Suppl 1):S3–S9. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000195385.19268.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanauer S, Schwartz J, Robinson M, et al. Mesalamine capsules for treatment of active ulcerative colitis: results of a controlled trial. Pentasa Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1188–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron JH, Connell AM, Kanaghinis TG, Lennard-Jones JE, Jones AF. Out-patient treatment of ulcerative colitis. Comparison between three doses of oral prednisone. Br Med J. 1962;2:441–443. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5302.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone and corticotrophin in ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1959;1:387–394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5119.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto S, Nakase H, Mikami S, et al. Long-term effect of tacrolimus therapy in patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:589–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Reinisch W, et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved longterm clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1194–1201. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yokoyama K, Kobayashi K, Mukae M, Sada M, Koizumi W. Clinical study of the relation between mucosal healing and longterm outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:192794. doi: 10.1155/2013/192794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Höie O, Wolters F, Riis L, et al. Ulcerative colitis: patient characteristics may predict 10-yr disease recurrence in a European-wide population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1692–1701. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dignass A, Eliakim R, Magro F, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 1: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:965–990. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763–786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright R, Truelove SR. Serial rectal biopsy in ulcerative colitis during the course of a controlled therapeutic trial of various diets. Am J Dig Dis. 1966;11:847–857. doi: 10.1007/BF02233941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeya K, Sugimoto K, Kawasaki S, et al. Tacrolimus for remission induction in ulcerative colitis: Mayo endoscopic subscore 0 and 1 predict long-term prognosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.01.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barreiro-de Acosta M, Vallejo N, de la Iglesia D, et al. Evaluation of the risk of relapse in ulcerative colitis according to the degree of mucosal healing (Mayo 0 vs 1): a longitudinal cohort study [published online ahead of print September 8, 2015] J Crohns Colitis. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut. 2012;61:1619–1635. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bitton A, Peppercorn MA, Antonioli DA, et al. Clinical, biological, and histologic parameters as predictors of relapse in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:13–20. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bessissow T, Lemmens B, Ferrante M, et al. Prognostic value of serologic and histologic markers on clinical relapse in ulcerative colitis patients with mucosal healing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1684–1692. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macé V, Ahluwalia A, Coron E, et al. Confocal laser endomicroscopy: a new gold standard for the assessment of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(Suppl 1):85–92. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, et al. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up [published online ahead of print May 18, 2015] Gut. 2015 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]