Abstract

Background

Post-traumatic symptomatology is one of the signature effects of the pernicious exposures endured by responders to the World Trade Center (WTC) disaster of 11 September 2001 (9/11), but the long-term extent of diagnosed Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and its impact on quality of life are unknown. This study examines the extent of DSM-IV PTSD 11–13 years after the disaster in WTC responders, its symptom profiles and trajectories, and associations of active, remitted and partial PTSD with exposures, physical health and psychosocial well-being.

Method

Master's-level psychologists administered sections of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV and the Range of Impaired Functioning Tool to 3231 responders monitored at the Stony Brook University World Trade Center Health Program. The PTSD Checklist (PCL) and current medical symptoms were obtained at each visit.

Results

In all, 9.7% had current, 7.9% remitted, and 5.9% partial WTC-PTSD. Among those with active PTSD, avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms were most commonly, and flashbacks least commonly, reported. Trajectories of symptom severity across monitoring visits showed a modestly increasing slope for active and decelerating slope for remitted PTSD. WTC exposures, especially death and human remains, were strongly associated with PTSD. After adjusting for exposure and critical risk factors, including hazardous drinking and co-morbid depression, PTSD was strongly associated with health and well-being, especially dissatisfaction with life.

Conclusions

This is the first study to demonstrate the extent and correlates of long-term DSM-IV PTSD among responders. Although most proved resilient, there remains a sizable subgroup in need of continued treatment in the second decade after 9/11.

Key words: 9/11, Disaster responders, exposure, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosocial well-being, World Trade Center

Introduction

Responders to the World Trade Center (WTC) disaster of 11 September 2001 (9/11), particularly the men and women who were at the site on 11 September, were exposed to emotionally horrifying events and environmental toxins from multiple gases and fine airborne particulate matter from the collapse of the towers. The responders who participated in the rescue, recovery and clean-up operations included experienced workers with extensive training, such as police and firefighters, and non-traditional responders with no disaster training, such as construction workers, electricians, and transportation and utility workers (Dasaro et al. 2015). In the aftermath of the attacks, two programs were established to monitor responders' health and treat WTC-related conditions, one for police and non-traditional responders (World Trade Center Health Program; WTCHP) and one for New York City firefighters. In addition, the New York City Department of Health established the WTC Health Registry to track the health and well-being of individuals directly exposed to the collapse of the towers or its immediate aftermath.

All three programs obtained serial data on post-traumatic stress symptoms from the PTSD Checklist (PCL) (Blanchard et al. 1996). During the first decade after 9/11, 5–23% of responders had PCL scores suggestive of possible post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Liu et al. 2014), with higher rates among non-traditional compared with professional responders (Perrin et al. 2007; Ozbay et al. 2013). Trajectory analyses for responders who made three monitoring visits to the WTCHP found that 5.3% of police and 9.5% of non-traditional responders had chronically elevated symptoms, and 8.4% and 12.4%, respectively, experienced a reduction in symptom severity (Pietrzak et al. 2014). A recent analysis of responders in the WTC Health Registry found that half of police responders with probable PTSD in the first few years after 9/11 continued to have probable PTSD at 10–11 year follow-up (Cone et al. 2015).

WTC exposures, particularly being in the dust cloud and death of colleagues, were significantly associated with self-report PTSD symptoms (e.g. Perrin et al. 2007; Yip et al. 2015) independent of demographic and other risk factors (Friedman et al. 2013). In addition, consistent with the broader literature (O'Toole & Catts, 2008; McFarlane, 2010; Pacella et al. 2013), PTSD symptom severity was significantly associated with responders' physical health, particularly respiratory symptoms, a hallmark medical outcome of WTC exposures (Webber et al. 2011; Wisnivesky et al. 2011; Luft et al. 2012; Nair et al. 2012; Friedman et al. 2013; Pietrzak et al. 2014; Cone et al. 2015; Kotov et al. 2015). The temporal order has not been firmly established, but recent evidence suggests that PTSD symptoms drive the relationship rather than the converse (Kotov et al. 2015). Far fewer WTC responder studies have addressed the relationships of PTSD symptoms with psychosocial well-being (e.g. Stellman et al. 2008; Schwarzer et al. 2014) even though PTSD symptoms are an impediment to quality of life (Koenen et al. 2008) and increase the risk of depression (Breslau et al. 2000; Stander et al. 2014).

All of the studies described above are based on a probable diagnosis of PTSD from the PCL. In contrast, most other research on trauma established the diagnosis of PTSD from structured or semi-structured diagnostic interviews. Indeed, a longitudinal study of returning National Guard soldiers found that the best PCL cut-scores produced 65–76% false-positive errors in relation to a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) PTSD diagnosis (Arbisi et al. 2012), and a study of WTC firefighters suggested that the cut-points used by WTC investigators may be too high (Chiu et al. 2011). We found three studies of WTC responders that included a diagnostic interview. Two used the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al. 1995). The first, conducted with mental health relief workers 6–8 months after 9/11, found that 6.4% met criteria for WTC-related PTSD (Zimering et al. 2006). The second study focused on utility workers and found that PTSD declined from 14.9% in 2002 to 5.8% in 2008 (Cukor et al. 2011). Cukor et al. (2011) also reported that partial PTSD, defined as meeting cluster B and either cluster C or D criteria, decreased from 17.9% to 7.7%. The third study administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule to a large sample of retired firefighters in 2006–2007; 6.5% had current DSM-IV PTSD (Chiu et al. 2011). Thus, no study assessed WTC-related DSM-IV PTSD in police, who were critical first responders on 9/11, or in heterogeneous samples of non-traditional rescue/recovery workers, who had no training in disaster response. We also lack adequate information on the clinical profiles of responders with DSM-IV PTSD and the relative effects of persistent and remitted PTSD on health and psychosocial well-being.

To fill these gaps, we assessed a large cohort of WTCHP police and non-traditional responders in 2012–2014 with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al. 1996) and the Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (RIFT) (Leon et al. 1999) in order to examine: (1) the percentage of responders developing WTC-PTSD; (2) the criterion symptoms most frequently endorsed by active cases; (3) the comparative course of PCL symptoms for responders with active, remitted, partial and no WTC-PTSD; (4) the effects of physical and psychological exposures on long-term WTC-PTSD; and (5) associations of active, remitted and partial WTC-PTSD with current health and psychosocial well-being.

Method

Setting

The sample was derived from the Long Island/Stony Brook University WTCHP, the second largest of five Clinical Centers of Excellence in the New York metropolitan area (Dasaro et al. 2015). Enrollees with documented WTC experience were enlisted from extensive outreach efforts involving partnerships with volunteer organizations, labor unions and public outlets.

The protocol and consent form for the current study were approved annually by the Committees on Research Involving Human Subjects at Stony Brook University. Written informed consent was obtained. Assessments took place during regularly scheduled monitoring visits between January 2012 and May 2014.

Participants

Among the 4587 responders monitored during the study period, 23 could not be approached due to inadequate English language skills. Of the remainder, 430 declined, 630 did not have time to complete the interview, and 3504 participated (76.8% of eligible responders). Their demographic and occupational characteristics (Table 1) are in line with those of the clinic population as a whole.

Table 1.

Characteristics of responders and associations with DSM-IV WTC-PTSD

| No diagnosis (n = 2660), n (%) | WTC-PTSD (n = 571), n (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of responder | |||

| Non-traditional | 719 (27.0) | 238 (41.7) | 1.9 (1.6–2.3)* |

| Police | 1941 (73.0) | 333 (58.3) | 1.0 |

| Age at 11 September 2001 | |||

| ⩾40 years | 1051 (39.5) | 230 (40.3) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) |

| <40 years | 1609 (60.5) | 341 (59.7) | 1.0 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 206 (7.7) | 74 (13.0) | 1.8 (1.3–2.4)* |

| Male | 2454 (92.3) | 497 (87.0) | 1.0 |

| Education a | |||

| Less than college | 1858 (69.8) | 419 (73.4) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 802 (30.2) | 152 (26.6) | 1.0 |

| Employment (initial visit) a | |||

| Not working | 96 (3.7) | 83 (14.8) | 5.0 (3.7–6.9)* |

| Retired | 281 (10.8) | 95 (17.0) | 2.0 (1.4–2.6)* |

| Employed full/part time | 2221 (85.5) | 381 (68.2) | 1.0 |

| Marital status (initial visit) a | |||

| Not married | 497 (19.0) | 140 (25.0) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8)* |

| Married/with partner | 2114 (81.0) | 421 (75.0) | 1.0 |

| Race | |||

| Other | 572 (21.5) | 113 (19.8) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) |

| Caucasian | 2088 (78.5) | 458 (80.2) | 1.0 |

| Smoking status a | |||

| Current smoker | 159 (6.0) | 77 (13.7) | 2.5 (1.9–3.3)* |

| Not current smoker | 2475 94.0) | 484 (86.3) | 1.0 |

| Hazardous drinker a | |||

| Yes, current | 95 (4.3) | 72 (14.6) | 3.8 (2.8–5.3)* |

| No | 2132 (95.7) | 420 (85.4) | 1.0 |

| Current major depression a | |||

| Yes | 47 (1.8) | 218 (38.2) | 34.4 (24.6–48.1)* |

| No | 2612 (98.2) | 352 (61.8) | 1.0 |

| Number of monitoring visits | |||

| 3+ | 1937 (72.8) | 422 (73.9) | 1.1 (0.86–1.3) |

| 1–2 | 723 (27.2) | 149 (26.1) | 1.0 |

| Mental health treatment since 11 September 2001 | |||

| Yes | 628 (23.6) | 435 (76.2) | 10.4 (8.4–12.8)* |

| No | 2032 (76.4) | 136 (23.8) | 1.0 |

DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; WTC, World Trade Center; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Missing values.

p ⩽ 0.001.

PTSD

DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis

Master's level psychologists were trained to administer the SCID PTSD module without skip-outs (First et al. 1996) with interval instructions (worst episode of symptoms since 11 September 2001). SCID items were modified to assess PTSD symptoms in relation to traumatic WTC exposures (criterion A). Before conducting the assessment, the interviewers reviewed participants' occupational and medical histories in order to facilitate rapport and enhance accurate interpretation of responses, particularly to physiological items. Inter-rater agreement for 55 independently rated audiotapes was very good (κ = 0.82).

PTSD diagnoses were considered active if current in the past month, remitted if criteria were met in the past only, and partial if DSM-IV criteria were not met but at least one symptom in the B, C and D clusters was endorsed (Breslau et al. 2004).

PTSD symptom severity

As noted, at each monitoring visit, responders completed the PCL-S (specific version) (Blanchard et al. 1996), a 17-item self-report measure modified to assess symptoms over the past month ‘in relation to 9/11’. Severity is rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The PCL has good convergent validity and internal consistency (Wilkins et al. 2011). In the present sample, the internal consistency was excellent (α = 0.96). Of note, only 58.8% of responders with active WTC-PTSD had a PCL score indicating possible PTSD (⩾50; Terhakopian et al. 2008).

WTC exposures

Exposure was systematically assessed at the first monitoring visit (Dasaro et al. 2015). Six variables were included in the analysis: caught in the dust cloud; early arrival (e.g. on 11 or 12 September; of those arriving later, only 84 arrived after 30 September); duration of work (⩾19 days in September, which was the top quartile, v. fewer days); exposure to human remains; knowing someone who was injured; and death of colleagues, friends or family in the tower collapse. A three-level severity index was created to define no/low (0–2), intermediate (3–4) and high (5–6) exposure levels. In the high exposure category, 98.6% lost a colleague or loved one.

Health and psychosocial well-being

Health variables were: (1) lower respiratory symptoms (cough, wheezing, chest tightness and/or shortness of breath) assessed by medical staff and categorized as WTC-related if absent before or significantly worse following 9/11 and not due exclusively to a cold or similar infection (Luft et al. 2012); (2) body mass index ⩾35 kg/m2 (e.g. class II obesity or higher) calculated from height and weight measurements; and (3) fair/poor/very poor self-rated health (v. good/very good) (Idler & Benyamini, 1997). Psychosocial well-being was determined from interviewer ratings on the RIFT of life satisfaction, relationships with friends and social network involvement (Leon et al. 1999). Items were dichotomized into fair/poor/very poor life satisfaction v. good/very good, mild/moderate/severely impaired relationships with friends v. satisfactory/non-impaired, and fair/poor social network involvement v. good/very good.

General risk factors

These included type of responder [police v. non-traditional (primarily construction workers)], age on 9/11 (<40 v. ⩾40 years), gender, education (⩾bachelor's degree v. lower), occupational status at initial monitoring visit (employed full or part time, retired, not working), marital status at initial visit (married/with partner v. separated/divorced/widowed), race (Caucasian; other), current cigarette smoking (Welch et al. 2015), current hazardous drinking (⩾8 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; AUDIT-10) (Bohn et al. 1995) and current DSM-IV major depressive episode (assessed with the SCID). Two service use variables were also included: number of prior monitoring visits and mental health treatment since 9/11 (self-reported use of mental health services at either the initial monitoring visit or study assessment or filing a psychotherapy treatment claim with the WTCHP).

Statistical analysis

The analyses focused on 3231 Stony Brook responders (92.2% of the sample) with complete information on PTSD, dust cloud exposure and loss of colleagues in the tower collapse. We calculated the percentage of Stony Brook responders who developed PTSD and also estimated the rate for the WTCHP general cohort (n = 33 076) by applying weights (Winship & Radbill, 1994) to adjust for the distribution of males (85.6%), Caucasians (56.7%) and police (49%) in the cross-center cohort (Dasaro et al. 2015).

Relationships of exposure, health and psychosocial functioning with PTSD were examined using binomial and multinomial logistic regression methods. Analyses were computed with SPSS version 23 (USA).

To examine the trajectories of PTSD symptoms among responders with active, remitted, partial and no DSM-IV PTSD, we used PCL data collected over one to nine monitoring visits, with observations occurring on average 1.6 (s.d. = 1.0) years apart. The analyses incorporated 23 085.8 person-years of observation. We used exact clinic visit dates to calculate years between WTC exposure and observation and years2 to examine the potential for non-linear changes over time. Because longitudinal analysis can be biased by repeat measurement and by individual differences in susceptibility or likelihood of reporting PTSD symptoms, we used longitudinal multilevel modeling. We modeled random intercepts, slopes and slopes2 to provide the best model fit. We assumed an unstructured covariance matrix to account for regression to the mean and ensure that results were robust to attrition under the assumption that such attrition is not due to an unexpectedly high or low PCL score. We modeled the following equation:

where PCL was measured among individuals (i) over time (t), PTSD4 was the four-category ordinal variable, vit indicated year of first monitoring visit and was incorporated to model change in sample make-up, and γki refers to random, within-person intercepts and slopes.

Ethical standards

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Results

The majority of the sample was male (91.3%), Caucasian (78.8%) and worked in law enforcement (70.4%) (Table 1). The median age on 9/11 was 38 years (90% range = 28–50 years). At their first monitoring visit, most were married (79.9%) and employed (82.4%). Less than 10% had current depression, were active smokers or engaged in hazardous drinking. Most had made at least three monitoring visits (73.0%) and one-third (32.9%) received some type of mental health treatment since 9/11.

Nearly one-fifth of the Stony Brook cohort (n = 571; 17.7%) developed WTC-PTSD. The estimated weighted rate for the WTCHP general responder cohort was 18.2%. As shown in Table 1, non-traditional responders were twice as likely to develop WTC-PTSD compared with police (24.9% v. 14.6%). Among police, the percentage with PTSD was significantly lower (p < 0.001) for active duty (12.0%) than retired officers (27.2%); among non-traditional responders, the percentages were similar (21.5% and 20.0%, respectively). Consistent with epidemiological findings, female gender, marital status and employment as well as smoking, hazardous drinking, current depression and mental health treatment were significantly associated with PTSD. As expected, current depression was strongly co-morbid with PTSD in both police and non-traditional responders.

With respect to recency, 9.7% (n = 315) of the sample had active PTSD and 7.9% (n = 256) were in remission. Thus, slightly more than half of the responders who developed PTSD (55.2%) had active disorder at the time of interview. This was true in both police (53.2%) and non-traditional responders (58.0%). Furthermore, 5.9% (n = 191) of the sample had partial PTSD, primarily in the past (two-thirds of partial cases). Partial PTSD was less frequent in police (6.3%) than in non-traditional responders (9.5%) (χ2 = 7.67, degrees of freedom = 1, p < 0.01).

PTSD symptoms

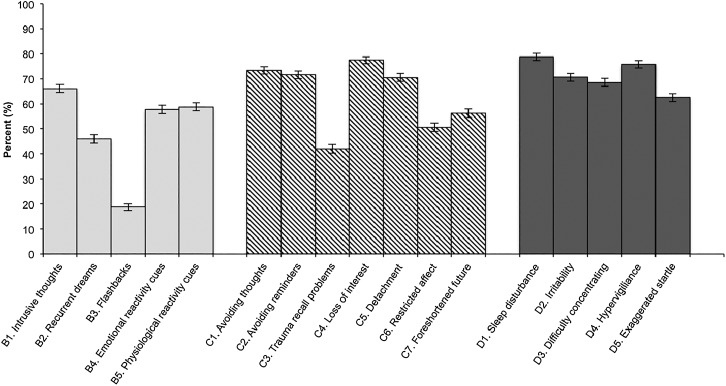

Fig. 1 shows the distribution of SCID PTSD symptoms for responders with active PTSD. More than two-thirds reported intrusive thoughts (B1), avoiding thoughts and reminders (C1–2), loss of interest and detachment (C4–5), and four of the five hyperarousal symptoms (D1–4). The least frequently reported symptoms were recurrent dreams and flashbacks (B2–3) and inability to recall aspects of the trauma (C3).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) criteria B (intrusive recollection), C (avoidance/numbing) and D (hyperarousal) symptoms among responders with active World Trade Center PTSD in 2012–2014. Values are percentages, with 95% confidence intervals represented by vertical bars.

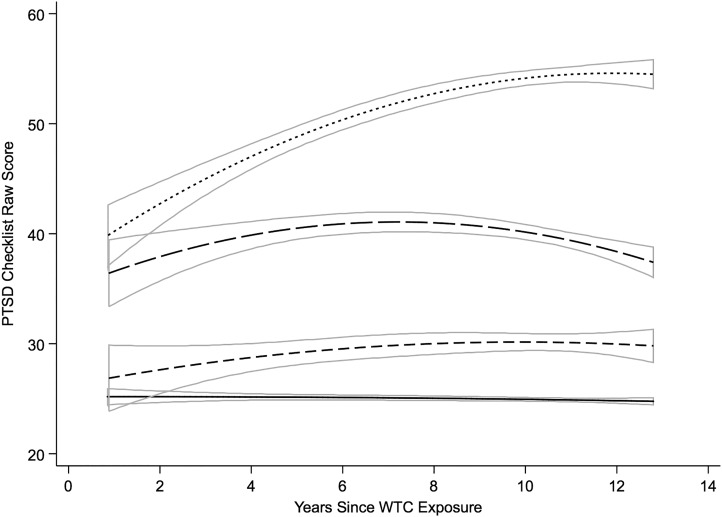

The trajectories of PCL symptoms across monitoring visits for responders with active, remitted and partial PTSD are shown in Fig. 2. The overall longitudinal associations are provided in online Supplementary Table S1, and fit statistics and reasoning for our model choice are provided in online Supplementary Table S2. We note that time of the first monitoring visit was not significantly associated with initial PCL score (online Supplementary Table S1). The random-effects intercepts suggest that there were individual differences in PTSD symptom severity, while the significant slope and slope2 covariates suggest that growth in PCL scores was heterogeneous over time. There was also a negative covariance between intercepts and slope and slope2, suggesting that those with higher scores were more likely to experience symptom reduction over time than those with lower capability. The strong negative correlation between individual slopes and slope2 suggests that those who experienced more rapid increases in PCL scores also tended to experience more deceleration, possibly indicative of floor and ceiling effects in the sensitivity of the PCL.

Fig. 2.

Predicted trajectories derived from longitudinal models of PTSD Checklist data for responders with no history of World Trade Center (WTC) post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (––), and partial (- - -), remitted (– – –) and active WTC-PTSD (· · ·). The boxes outlined in solid gray represent 95% confidence intervals.

Responders with active WTC-PTSD had the highest PCL scores at the initial monitoring visit which increased over time and then plateaued (Fig. 2). Responders with remitted PTSD had lower initial PCL scores that also increased over time but then decelerated. In contrast, responders with partial PTSD were similar initially to those with no history of PTSD, but their PCL scores increased in a linear fashion over time while those without PTSD retained their low PCL scores.

Exposure and PTSD

One-quarter of the sample arrived on 11–12 September (25.2%), and one-quarter were in the dust cloud (23.0%). More than half were exposed to human remains (71.5%), knew someone who was injured on 9/11 (56.0%), or suffered a loss (68.1%), primarily of colleagues (78.1% of deaths). One-quarter (23.7%) experienced five to six exposures. Police responders were significantly more likely (p < 0.001) to report each exposure and were twice as likely as non-traditional responders to be in the high exposure category (28.4% v. 12.4%).

Because responder type was significantly associated with both exposure and PTSD, we analysed the associations of exposure with PTSD separately for police and non-traditional responders. Table 2 shows that among police, each exposure increased the risk of WTC-PTSD and of active, remitted and, to a lesser extent, partial PTSD. The largest odds ratios were for exposure to human remains and experiencing five to six exposures. Among non-traditional responders, the associations of exposures with WTC-PTSD and with active and remitted PTSD were also significant, albeit somewhat weaker. Associations with partial PTSD were by and large non-significant with the exceptions of arrival on 11–12 September, which increased the risk of partial PTSD three-fold, and being in the highest exposure category, which more than doubled the risk.

Table 2.

Relationships of exposures to WTC-PTSD compared with partial/no PTSD, and with active, remitted and partial PTSD compared with no PTSD

| WTC-PTSD | Active PTSD | Remitted PTSD | Partial PTSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Police responders (n = 2274) | ||||

| Exposure type | ||||

| Arrival 11–12 | 1.9 (1.3–2.6)*** | 1.9 (1.2–3.0)** | 2.0 (1.2–3.2)** | 1.9 (1.1–3.3)* |

| September | ||||

| In dust cloud | 1.9 (1.5–2.4)*** | 1.8 (1.3–2.5)*** | 2.2 (1.6–3.1)*** | 1.8 (1.2–2.6)* |

| Worked >19 days | 1.5 (1.2–1.9)*** | 1.6 (1.1–2.2)** | 1.6 (1.1–2.2)** | 1.5 (1.0–2.2)* |

| Human remains | 3.0 (2.0–4.6)*** | 3.6 (2.0–6.5)*** | 2.6 (1.5–4.6)*** | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) |

| Injury | 2.1 (1.6–2.7)*** | 2.1 (1.5–3.0)*** | 2.2 (1.5–3.1)*** | 1.5 (1.0–2.2)* |

| Death | 2.4 (1.7–3.4)*** | 2.5 (1.6–3.9)*** | 2.4 (1.5–3.8)*** | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) |

| Exposure severity (number) | ||||

| High (5–6) | 3.8 (2.4–6.1)*** | 4.8 (2.4–9.8)*** | 3.4 (1.8–6.2)*** | 2.2 (1.1–4.2)* |

| Intermediate (3–4) | 2.0 (1.2–3.1)*** | 2.8 (1.4–5.6)** | 1.4 (0.8–2.6) | 1.5 (0.8–2.8) |

| No/low (0–2) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Non-traditional responders (n = 957) | ||||

| Exposure type | ||||

| Arrival 11–12 | 1.9 (1.4–2.7)*** | 1.9 (1.2–2.8)** | 2.5 (1.5–4.3)*** | 3.3 (1.7–6.4)*** |

| September | ||||

| In dust cloud | 2.0 (1.4–2.9)*** | 1.8 (1.1–2.8)* | 2.7 (1.7–4.4)*** | 1.6 (0.9–3.1) |

| Worked >19 days | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 1.8 (0.9–3.3) |

| Human remains | 2.0 (1.4–2.8)*** | 1.9 (1.2–2.8)** | 2.3 (1.4–3.8)*** | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) |

| Injury | 1.9 (1.3–2.5)*** | 2.0 (1.4–2.9)*** | 1.9 (1.2–2.9)** | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) |

| Death | 1.6 (1.2–2.1)** | 1.9 (1.3–2.8)*** | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) |

| Exposure severity (number) | ||||

| High (5–6) | 2.9 (1.8–4.5)*** | 3.4 (1.9–6.2)*** | 3.0 (1.6–5.5)*** | 2.4 (1.2–5.1)* |

| Intermediate (3–4) | 1.5 (1.1–2.1)* | 1.9 (1.2–2.9)** | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) |

| No/low (0–2) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

WTC, World Trade Center; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; AOR, adjusted odds ratio.

* p < 0.05, ** p ⩽ 0.01, *** p ⩽ 0.001.

Relationships of WTC-PTSD with health and psychosocial well-being

Table 3 shows the relationships between WTC-PTSD and health and psychosocial well-being. Findings from the unadjusted analyses indicated that WTC-PTSD, especially active PTSD, was significantly associated with each of the health and psychosocial variables. In addition, we found a set of graded relationships across active, remitted and partial PTSD for each variable except severe obesity. After adjusting for exposure severity, demographic characteristics and other PTSD risk factors (smoking, hazardous drinking, depression, mental health treatment), WTC-PTSD was significantly associated with respiratory symptoms, subjective health, life satisfaction and social support, but not severe obesity or poorer relationships with friends. The graded pattern of relationships with active, remitted and partial PTSD was diminished with the exception of life satisfaction, on which responders with active PTSD were more than seven times as likely and those with remitted PTSD more than twice as likely than unaffected responders to be rated as having fair/poor satisfaction. The adjusted odds ratio for partial PTSD with life satisfaction was not significant.

Table 3.

Associations of WTC-PTSD with health and well-being: binomial and multinomial logistic regression analyses

| Unadjusted analysis | Adjusted analysis a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTC-PTSD v. partial/none | Active PTSD | Remitted PTSD | Partial PTSD | None | WTC-PTSD v. partial/none | Active PTSD | Remitted PTSD | Partial PTSD | None | |

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | Ref | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | Ref |

| Health status | ||||||||||

| Respiratory symptoms | 2.7 (2.3–3.3)*** | 4.6 (3.5–5.9)*** | 1.6 (1.3–2.1)*** | 1.4 (1.0–1.8)* | 1.0 | 1.7 (1.3–2.2)*** | 2.6 (1.8–3.8)*** | 1.4 (1.0–1.9)* | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 1.0 |

| BMI ⩾35 kg/m2 | 1.3 (1.1–1.7)** | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.5 (1.1–2.0)** | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 1.0 | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 1.5 (1.0–2.1)* | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.0 |

| Fair/poor health | 4.4 (3.6–5.3)*** | 7.6 (5.8–9.9)*** | 2.7 (2.1–3.5)*** | 1.7 (1.3–2.4)*** | 1.0 | 1.9 (1.5–2.5)*** | 2.6 (1.7–3.7)*** | 1.8 (1.3–2.4)*** | 1.7 (1.2–2.4)** | 1.0 |

| Psychosocial status | ||||||||||

| Fair/poor satisfaction | 10.5 (8.5–12.9)*** | 28.1 (20.3–38.9)*** | 4.8 (3.7–6.3)*** | 1.8 (1.2–2.5)** | 1.0 | 3.5 (2.7–4.7)*** | 7.6 (4.9–11.7)*** | 2.4 (1.7–3.4)*** | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 1.0 |

| Impaired friendships | 2.4 (1.9–2.9)*** | 3.7 (2.9–4.8)*** | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 1.0 | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.9 (1.2–2.8)** | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 1.0 |

| Fair/poor social support | 2.5 (2.1–3.1)*** | 3.7 (2.9–4.8)*** | 1.7 (1.3–2.2)*** | 1.4 (1.1–2.0)* | 1.0 | 1.4 (1.2–2.0)** | 2.2 (1.5–3.1)*** | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | 1.0 |

WTC, World Trade Center; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; aOR, odds ratio in multinomial regression; ref, reference; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index.

Adjusted for variables significant in Tables 1 and 2: responder type, exposure severity, gender, employment, marital status, smoking, hazardous drinking, current depression and mental health treatment since 11 September 2001.

* p < 0.05, ** p ⩽ 0.01, *** p ⩽ 0.001.

Discussion

Nearly one-fifth of the WTC responders monitored at the second largest WTCHP developed DSM-IV WTC-PTSD after 9/11, half of whom had active disorder 11–13 years on. The most frequent symptoms in the active PTSD group were avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms, while intrusive recollection symptoms were less commonly endorsed. The longitudinal trajectories of PTSD symptomatology rated on the PCL showed a modestly increasing slope for responders with active PTSD and a decelerating pattern for the remitted group. More than a decade after 9/11, WTC exposures remained strongly predictive of both active and remitted PTSD, especially among police responders. WTC-PTSD was strongly associated with health and psychosocial well-being. While these relationships were attenuated after adjustment for exposure, demographic characteristics and known risk factors for PTSD, including depression, they remained robust more than a decade after 9/11, particularly among responders with active WTC-PTSD.

This is the first study of a broad sample of professional and non-traditional WTC responders designed to examine the extent of DSM-IV WTC-related PTSD based on a clinician-administered diagnostic assessment (SCID) and associations with psychosocial well-being determined from a reliable semi-structured interview (RIFT). The interviewing team was composed of master's-level clinical psychologists who reviewed medical records prior to each interview to enhance the accuracy of the assessments. A key emphasis of the training was distinguishing between symptoms directly related to 9/11 exposures and ones that were secondary to 9/11 physical illnesses, particularly respiratory and gastrointestinal conditions. An additional strength was the inclusion of a comprehensive set of potential confounders, including hazardous drinking, smoking, current DSM-IV depression and mental health service use, in analysing associations of active, remitted and partial PTSD with health and psychosocial well-being.

The findings, however, require independent confirmation. Similar to other major disasters, such as the Amsterdam El Al crash (e.g. Huizink et al. 2006), the Oklahoma City bombing (North et al. 2002) and the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident (Loganovsky et al. 2008), there is no complete list of WTC responders. The three largest cohorts are the WTCHP, which verifies responder status, the New York City firefighter cohort, requiring annual examinations starting before 9/11, and the WTC Health Registry, where inclusion is based on self-report. Although the percentages reported here should be regarded cautiously, our findings are consistent with those of previous studies of WTC responders and research on other rescue/recovery workers. For example, the proportion of police responders with active (current) PTSD (7.8%) is in line with the estimate for WTC retired firefighters 7 years after 9/11 (6.5%; Chiu et al. 2011) and with the global pooled estimate of 10% reported in a recent meta-analysis of a worldwide sample of >20 000 rescue workers (Berger et al. 2012). The percentage with post-9/11 PTSD in our sample (17.7%) and the weighted percentage for the entire WTCHP (18.2%) are consistent with the lifetime rate of 18.7% in the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS) theater cohort assessed with the SCID 20–25 years later (Dohrenwend et al. 2008). Furthermore, the associations reported here for exposure, demographic and other risk factors are consistent with findings from previous trauma studies (McFarlane, 2010; Del Gaizo et al. 2011; Kilpatrick et al. 2013). Second, like other large-scale studies (e.g. NVVRS, Schlenger et al. 2007; Project VALOR, Rosen et al. 2012), we administered the SCID rather than the ‘gold standard’ CAPS primarily because of time constraints. Third, the study was cross-sectional and observational though the inclusion of serial symptom data enriched the clinical results. Fourth, like other WTC studies, we did not have an unexposed comparison group. Last, this report focused exclusively on WTC-PTSD. However, responders were also at increased risk of depression and other anxiety disorders (Fullerton et al. 2004; Alexander & Klein, 2009) and were exposed to prior and subsequent stressors. A recent study found an interaction effect of WTC exposure and post-9/11 stressful life events on PTSD symptomatology (Zvolensky et al. 2015). Future studies of DSM-IV PTSD in WTC responders will directly address these co-morbidities and sources of stress.

Within the context of these limitations, the current study sheds light on three issues. First, more than a decade after 9/11, the catastrophic exposures continued to have an adverse impact on clinically defined PTSD in both professional and non-traditional WTC responders. Although every disaster is unique, the findings add to the few long-term follow-ups of traumatic events, including Chernobyl clean-up workers (Loganovsky et al. 2008), Vietnam veterans (Schlenger et al. 2007) and Israeli combat veterans (Solomon et al. 2009). The percentage of police with active PTSD (7.8%) was lower than that of non-traditional responders (14.4%) and also lower than the rate of probable PTSD in police in the WTC Health Registry assessed with the PCL (11.0% in 2011–2012; Cone et al. 2015). It has been argued that active-duty police minimize their symptoms because of employment-related concerns (Luft et al. 2012), and, indeed, a lower percentage of active-duty police had WTC-PTSD compared with retired police officers. Even with this potential bias, the persistence of PTSD is striking, with approximately 50% of affected responders having active PTSD. Interestingly, the percentage with remitted PTSD 12–14 years post-9/11 was comparable with the median time to remission (14 years) for participants with PTSD in the 2007 Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (Chapman et al. 2012).

Second, although the diagnosis of PTSD connotes ‘flashbacks’ and ‘nightmares’ in popular culture, these symptoms were far less frequently reported than avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms. Furthermore, the trajectory of PTSD symptoms among responders with active PTSD showed progressively increasing symptom severity, indicating both unmet need for treatment and potential undertreatment for those receiving mental health services. Although ‘gold standard’ treatments, such as cognitive–behavioral therapy and prolonged exposure therapy, were designed to address PTSD symptoms, a recent meta-analysis (Watts et al. 2013) showed that these treatments potentially benefit only one in two patients. Even so, given that 50% of responders with PTSD had active disorder, there is a clear need to continue to monitor the cohort and to encourage the group with active PTSD to seek evidence-based treatment.

Third, PTSD was significantly associated with several aspects of health and psychosocial well-being, especially self-reported fair/poor health and reduced life satisfaction. Even after adjustment for exposure severity and other risk factors, the reach of PTSD into other domains of life was clearly shown and was strongest for the group with active PTSD. The current associations with the health variables, especially respiratory symptoms and negative subjective evaluations obtained as part of the monitoring visit, are consistent with the recent national initiative to provide integrated physical and mental health care (Huffman et al. 2014). The findings also suggest that a biopsychosocial formulation should be an integral part of treatment planning. In fact, the Stony Brook clinic is modeled on an integrated physical and mental health care system, offering on-site mental and physical health care (Luft et al. 2012).

In conclusion, the long-term impact of 9/11 exposures, like combat experiences in military cohorts, is reflected in the substantial percentage with PTSD more than a decade after 9/11 and its strong associations with physical health and psychosocial well-being, especially reduced satisfaction with life. Responders experienced multiple exposures simultaneously and, like other rescue/recovery workers, were at increased risk by virtue of the combination of proximity to the disaster site, duration of work and intensity of the exposures (Benedek et al. 2007). The concurrent associations with poorer health and psychosocial well-being were striking, particularly for responders with active PTSD though the remitted group also had a 2-fold increased level of dissatisfaction with life and negative subjective health. These results suggest the need for monitoring programs to consider all aspects of health as defined by the World Health Organization, namely, mental, physical and social well-being. Future longitudinal studies are needed to determine the continued persistence of PTSD in this cohort, the potential for relapse among remitted cases and for delayed onset in the unaffected group, and the extent to which the course of PTSD predicts decrements in health and psychosocial well-being during the second decade after 9/11.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (CDC/NIOSH) grant 200-2011-39410 to E.J.B., R.K. and B.J.L.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the WTC responders for generously contributing their time and energy to this project. We also thank the following staff of the Stony Brook WTCHP for facilitating the study: Peter Arce, Julie Broihier, Katherine Guerrera, Janet Lavelle, Nicole Lee, Brittain Mahaffey, Lindsay Pratt, and Nwakaego (Ada) Ukonu, Oren Shapira, Ph.D., Chris Ray and the WTCHP Data Monitoring Center which provided invaluable assistance with securing data. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of NIOSH, the CDC or the US Public Health Service.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002184.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- Alexander DA, Klein S (2009). First responders after disasters: a review of stress reactions, at-risk, vulnerability, and resilience factors. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 24, 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbisi PA, Kaler ME, Kehle-Forbes SM, Erbes CR, Polusny MA, Thuras P (2012). The predictive validity of the PTSD Checklist in a nonclinical sample of combat-exposed National Guard troops. Psychological Assessment 24, 1034–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedek DM, Fullerton C, Ursano RJ (2007). First responders: mental health consequences of natural and human-made disasters for public health and public safety workers. Annual Review of Public Health 28, 55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger W, Coutinho ES, Figueira I, Marques-Portella C, Luz MP, Neylan TC, Marmar CR, Mendlowicz MV (2012). Rescuers at risk: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of the worldwide current prevalence and correlates of PTSD in rescue workers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 47, 1001–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM (1995). The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress 8, 75–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research and Therapy 34, 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR (1995). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 56, 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, Schultz LR (2000). A second look at comorbidity in victims of trauma: the posttraumatic stress disorder–major depression connection. Biological Psychiatry 48, 902–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Lucia VC, Davis GC (2004). Partial PTSD versus full PTSD: an empirical examination of associated impairment. Psychological Medicine 34, 1205–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman C, Mills K, Slade T, McFarlane AC, Bryant RA, Creamer M, Silove D, Teesson M (2012). Remission from post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population. Psychological Medicine 42, 1695–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu S, Webber MP, Zeig-Owens R, Gustave J, Lee R, Kelly KJ, Rizzotto L, Schorr JK, North CS, Prezant DJ (2011). Performance characteristics of the PTSD Checklist in retired firefighters exposed to the World Trade Center disaster. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 23, 95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone JE, Li J, Kornblith E, Gocheva V, Stellman SD, Shaikh A, Schwarzer R, Bowler RM (2015). Chronic probable PTSD in police responders in the World Trade Center Health Registry ten to eleven years after 9/11. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 58, 483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukor J, Wyka K, Mello B, Olden M, Jayasinghe N, Giosan C, Crane M, Difede J (2011). The longitudinal course of PTSD among disaster workers deployed to the World Trade Center following the attacks of September 11th. Journal of Traumatic Stress 24, 506–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasaro CR, Holden WL, Berman KD, Crane MA, Kaplan JR, Lucchini RG, Luft BJ, Moline JM, Teitelbaum SL, Tirunagari US, Udasin IG, Weiner JH, Zigrossi PA, Todd AC (2015). Cohort profile: World Trade Center Health Program General Responder Cohort. International Journal of Epidemiology. Published online 20 June 2015. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Gaizo AL, Elhai JD, Weaver TL (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder, poor physical health and substance use behaviors in a national trauma-exposed sample. Psychiatry Research 88, 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP, Turner JB, Turse NA, Lewis-Fernandez R, Thomas J, Yager TJ (2008). War-related post-traumatic stress disorder in black, Hispanic, and majority white Vietnam veterans: the roles of exposure and vulnerability. Journal of Traumatic Stress 21, 133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBM (1996). Structured Clinical Interview Diagnosis (SCID) for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Clinician Version (SCID-CV). American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SM, Farfel MR, Maslow CB, Cone JE, Brackbill RM, Stellman SD (2013). Comorbid persistent lower respiratory symptoms and posttraumatic stress disorder 5–6 years post-9/11 in responders enrolled in the World Trade Center Health Registry. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 56, 1251–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Wang L (2004). Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or rescue workers. American Journal of Psychiatry 161, 1370–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman JC, Niazi SK, Rundell JR, Sharpe M, Katon WJ (2014). Essential articles on collaborative care models for the treatment of psychiatric disorders in medical settings: a publication by the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Research and Evidence-Based Practice Committee. Psychosomatics 55, 109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC, Slottje P, Witteveen AB, Bijlsma JA, Twisk JW, Smidt N, Bramsen I, van Mechelen W, van der Ploeg HM, Bouter LM, Smid T (2006). Long term health complaints following the Amsterdam Air Disaster in police officers and fire-fighters. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 63, 657–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Benyamini Y (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38, 21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress 26, 537–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Stellman SD, Sommer JF Jr., Stellman JM (2008). Persistent posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and their relationship to functioning in Vietnam veterans: a 14-year follow-up. Journal of Traumatic Stress 21, 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Bromet EJ, Schechter C, Broihier J, Feder A, Friedman-Jimenez G, Gonzalez A, Guerrera K, Kaplan J, Moline J, Pietrzak RH, Reissman D, Ruggero C, Southwick SM, Udasin I, Von Korff M, Luft BJ (2015). Posttraumatic stress disorder and the risk of respiratory problems in World Trade Center responders: longitudinal test of a pathway. Psychosomatic Medicine 77, 438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon A, Solomon DA, Mueller TI, Turvey CL, Endicott J, Keller MD (1999). The Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (LIFE-RIFT): a brief measure of functional impairment. Psychological Medicine 29, 869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Tarigan LH, Bromet EJ, Kim HJ (2014). World Trade Center disaster exposure-related probable posttraumatic stress disorder among responders and civilians: a meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 9, . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loganovsky K, Havenaar JM, Tintle N, Tung L, Kotov RI, Bromet EJ (2008). The mental health of clean-up workers 18 years after the Chernobyl accident. Psychological Medicine 38, 481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft BJ, Schechter CB, Broihier J, Reissman DB, Guerrera K, Udasin I, Moline J, Harrison D, Freidman-Jimenez G, Pietrzak RH, Southwick SM, Bromet EJ (2012). Exposure, probable PTSD and lower respiratory illness among World Trade Center rescue, recovery and clean-up workers. Psychological Medicine 42, 1069–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC (2010). The long-term costs of traumatic stress: intertwined physical and psychological consequences. World Psychiatry 9, 3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair HP, Ekenga CC, Cone JE, Brackbill R, Farfel M, Stellman SD (2012). Co-occurring lower respiratory symptoms and posttraumatic stress disorder 5 to 6 years after the World Trade Center terrorist attack. American Journal of Public Health 102, 1964–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Tivis L, McMillen JC, Pfefferbaum B, Spitznagel EL, Cox J, Nixon S, Bunch KP, Smith EM (2002). Psychiatric disorders in rescue workers after the Oklahoma City bombing. American Journal of Psychiatry 159, 857–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole BI, Catts SV (2008). Trauma, PTSD, and physical health: an epidemiological study of Australian Vietnam veterans. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64, 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbay F, Auf der Heyde T, Reissman D, Sharma V (2013). The enduring mental health impact of the September 11th terrorist attacks: challenges and lessons learned. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 36, 417–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacella ML, Hruska B, Delahanty DL (2013). The physical health consequences of PTSD and PTSD symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 27, 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin MA, DiGrande L, Wheeler K, Thorpe L, Farfel M, Brackbill R (2007). Differences in PTSD prevalence and associated risk factors among World Trade Center disaster rescue and recovery workers. American Journal of Psychiatry 164, 1385–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Feder A, Singh R, Schechter CB, Bromet EJ, Katz CL, Reissman DB, Ozbay F, Sharma V, Crane M, Harrison D, Herbert R, Levin SM, Luft BJ, Moline JM, Stellman JM, Udasin I, Landrigan PJ, Southwick SM (2014). Trajectories of PTSD risk and resilience in World Trade Center responders: an 8-year prospective cohort study. Psychological Medicine 44, 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen RC, Marx BP, Maserejian NN, Holowka DW, Gates MA, Sleeper LA, Vasterling JJ, Kang HK, Keane TM (2012). Project VALOR: design and methods of a longitudinal registry of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in combat-exposed veterans in the Afghanistan and Iraqi military theaters of operations. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 21, 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenger WE, Kulka RA, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Weiss DS (2007). The psychological risks of Vietnam: the NVVRS perspective. Journal of Traumatic Stress 20, 467–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R, Bowler RM, Cone JE (2014). Social integration buffers stress in New York police after the 9/11 terrorist attack. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping 27, 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z, Horesh D, Ein-Dor T (2009). The longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters among war veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 70, 837–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stander VA, Thomsen CJ, Highfill-McRoy RM (2014). Etiology of depression comorbidity in combat-related PTSD: a review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review 34, 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellman JM, Smith RP, Katz CL, Sharma V, Charney DS, Herbert R, Moline J, Luft BJ, Markowitz S, Udasin I, Harrison D, Baron S, Landrigan PJ, Levin SM, Southwick S (2008). Enduring mental health morbidity and social function impairment in the World Trade Center rescue, recovery, and cleanup workers: the psychological dimension of an environmental health disaster. Environmental Health Perspectives 116, 1248–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terhakopian A, Sinaii N, Engel CC, Schnurr PP, Hoge CW (2008). Estimating population prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder: an example using the PTSD Checklist. Journal of Traumatic Stress 21, 290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts BV, Schnurr PP, Mayo L, Young Y, Weeks WB, Friedman MJL (2013). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 74, e541–e550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber MP, Glaser MS, Weakley J, Soo J, Ye F, Zeig-Owens R, Weiden MD, Nolan A, Aldrich T, Kelly K, Prezant D (2011). Physician-diagnosed respiratory conditions and mental health symptoms 7–9 years following the World Trade Center disaster. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 54, 661–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch AE, Jasek JP, Caramanica K, Chiles MC, Johns M (2015). Cigarette smoking and 9/11-related posttraumatic stress disorder among World Trade Center Health Registry enrollees, 2003–12. Preventive Medicine 73, 94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins KC, Lang A, Norman SB (2011). Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) military, civilian and specific versions. Depression and Anxiety 28, 569–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winship C, Radbill L (1994). Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociological Methods and Research 23, 230–257. [Google Scholar]

- Wisnivesky JP, Teitelbaum SL, Todd AC, Boffetta P, Crane M, Crowley L, de la Hoz RE, Dellenbaugh C, Harrison D, Herbert R, Kim H, Jeon Y, Kaplan J, Katz C, Levin S, Luft B, Markowitz S, Moline JM, Ozbay F, Pietrzak RH, Shapiro M, Sharma V, Skloot G, Southwick S, Stevenson LA, Udasin I, Wallenstein S, Landrigan PJ (2011). Persistence of multiple illnesses in World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers: a cohort study. Lancet 378, 888–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip J, Zeig-Owens R, Webber MP, Kablanian A, Hall CB, Vossbrinck M, Liu X, Weakley J, Schwartz T, Kelly KJ, Prezant DJ (2015). World Trade Center-related physical and mental health burden among New York City Fire Department emergency medical service workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. Published online 15 April 2015. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2014-102601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimering R, Gulliver SB, Knight J, Munroe J, Keane TM (2006). Posttraumatic stress disorder in disaster relief workers following direct and indirect trauma exposure to Ground Zero. Journal of Traumatic Stress 19, 553–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Farris SG, Kotov R, Schechter CB, Bromet E, Gonzalez A, Vujanovic A, Pietrzak R, Crane M, Kaplan J, Moline J, Southwick SM, Feder A, Udasin I, Reissman DB, Luft BJ (2015). World Trade Center disaster and sensitization to subsequent life stress: a longitudinal study of disaster responders. Preventive Medicine 75, 70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002184.

click here to view supplementary material