Abstract

The xylem conducts water and minerals from the root to the shoot and provides mechanical strength to the plant body. The vascular precursor cells of the procambium differentiate to form continuous vascular strands, from which xylem and phloem cells are generated in the proper spatiotemporal pattern. Procambium formation and xylem differentiation are directed by auxin. In angiosperms, thermospermine, a structural isomer of spermine, suppresses xylem differentiation by limiting auxin signalling. However, the process of auxin-inducible xylem differentiation has not been fully elucidated and remains difficult to manipulate. Here, we found that an antagonist of spermidine can act as an inhibitor of thermospermine biosynthesis and results in excessive xylem differentiation, which is a phenocopy of a thermospermine-deficient mutant acaulis5 in Arabidopsis thaliana. We named this compound xylemin owing to its xylem-inducing effect. Application of a combination of xylemin and thermospermine to wild-type seedlings negates the effect of xylemin, whereas co-treatment with xylemin and a synthetic proauxin, which undergoes hydrolysis to release active auxin, has a synergistic inductive effect on xylem differentiation. Thus, xylemin may serve as a useful transformative chemical tool not only for the study of thermospermine function in various plant species but also for the control of xylem induction and woody biomass production.

Polyamines such as putrescine and spermidine are small cationic amines present in all organisms that regulate various cellular functions1,2. In plants, polyamines play a role in physiological processes such as organogenesis, fruit development, stress responses, and cell death; in addition, they serve as precursors of numerous alkaloids3,4,5,6,7,8. The asymmetric tetraamine thermospermine is a structural isomer of the symmetric tetraamine spermine (Fig. 1a) and was first isolated from the thermophilic bacterium Thermus thermophilus9. Thermospermine is widely distributed throughout the plant kingdom3,10,11, and it has recently been identified as a novel plant growth regulator that represses xylem differentiation and promotes stem elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana12,13. Arabidopsis acaulis5-1 (acl5-1) is a loss-of-function mutant of ACL5, which encodes thermospermine synthase12,13, and exhibits excessive xylem differentiation and severe dwarfism14,15. In contrast, an Arabidopsis mutant defective in spermine biosynthesis shows wild-type morphology under normal growth conditions16 and spermine has been implicated in responses to biotic and abiotic stresses in plants3,4,5,6,7,8.

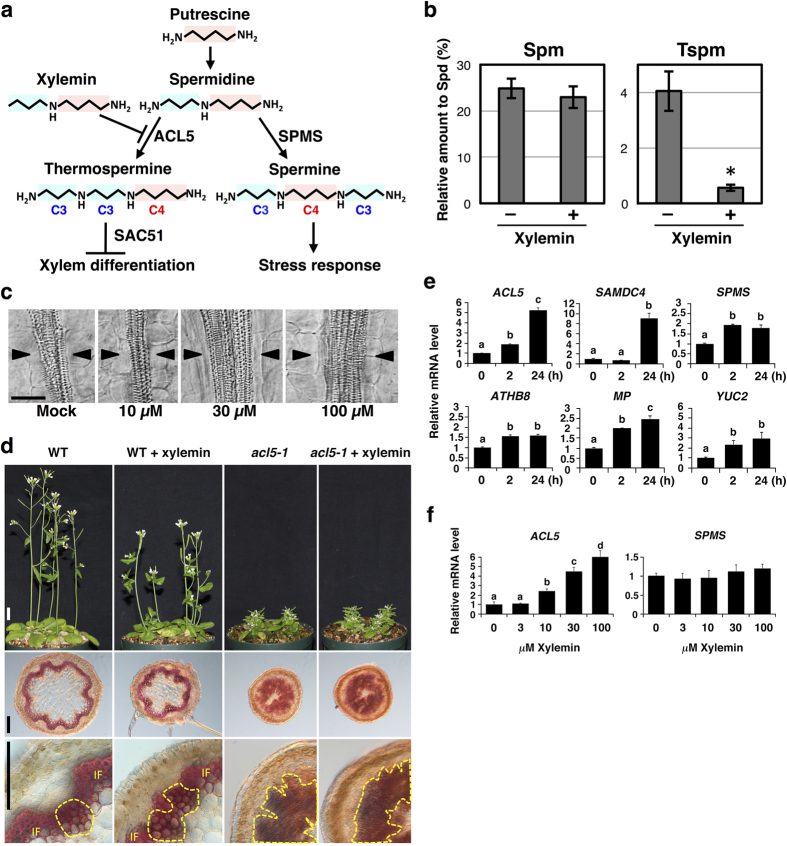

Figure 1. Xylemin promotes xylem differentiation by the inhibition of thermospermine synthesis.

(a) Biosynthetic pathway of polyamines in plants. (b) Effects of xylemin on the levels of spermine (Spm) and thermospermine (Tspm). The 7-day-old wild-type seedlings of Arabidopsis were transferred to the liquid medium with 10 μM spermidine (-Xylemin) or with 10 μM spermidine plus 30 μM xylemin (+Xylemin) and grown for 24 hours. The levels of polyamines were analyzed by HPLC. Data are displayed as averages ± SD (n = 3). Asterisk indicates significant differences from the value in the mock treatment (Student t-test, P < 0.01). (c) Effect of various concentrations of xylemin on xylem differentiation in hypocotyls. The wild type seedlings were germinated and grown for 7 days in the liquid medium with different concentrations of xylemin. Scale bar: 50 μm. (d) Shoot morphology and xylem differentiation in inflorescence stems of wild-type (WT) and acl5-1 plants treated with or without xylemin. Xylemin solution at the concentration of 100 μM was daily applied to each shoot apex. Xylem is indicated as the area enclosed by yellow dashed line. IF: interfascicular fiber. Scale bars: 1 cm (upper panels); 100 μm (middle and lower panels). (e) Response of gene expression to xylemin. Total RNA was isolated from the wild type seedlings grown for 7 days in the liquid medium and treated for 2 or 24 hours in the medium supplemented with 50 μM xylemin. All transcript levels are relative to those in mock-treated seedlings. Data are displayed as averages ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate Tukey’s HSD groupings (P < 0.05). (f) Effect of various concentrations of xylemin on expression of ACL5 and SPMS. Total RNA was isolated from the wild type seedlings grown for 7 days in the liquid medium with different concentrations of xylemin. All transcript levels are relative to mock controls. Data are displayed as averages ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate Tukey’s HSD groupings (P < 0.05).

In the course of chemical screening, we found that synthetic proauxins remarkably enhance xylem vessel differentiation in acl5-1 seedlings but not in the wild type17,18. Proauxin efficiently diffuses into the cells, undergoes cleavage and releases active auxin. The inductive effect of proauxins is completely suppressed by thermospermine, indicating that thermospermine negatively regulates auxin signalling that promotes xylem differentiation. In accordance with this scenario, thermospermine potently suppresses the expression of genes involved in auxin signalling, transport, and synthesis19. Together with the fact that ACL5 expression is up-regulated by auxin15 and down-regulated by thermospermine13, thermospermine may act in a negative feedback loop against auxin-induced xylem differentiation. A recent study showed that ATHB8, a member of the class III homeodomain-leucine zipper (HD-ZIP III) protein family directly activates ACL5 expression in this negative feedback loop20,21. HD-ZIP III transcriptional regulators including ATHB8 redundantly control xylem differentiation and patterning22,23. However, the molecular mechanism of action of thermospermine remains to be clarified. Polyamine biosynthesis inhibitors have been shown to be useful for the study of polyamine functions2. Here, we developed an antagonist of spermidine as an inhibitor of thermospermine biosynthesis and evaluated its inductive effect on xylem differentiation. Our results present new insights into the function of thermospermine in plants and on the chemical manipulation of xylem differentiation.

Results

Xylemin promotes xylem differentiation by suppressing thermospermine biosynthesis

Thermospermine synthase ACL5 catalyses the transfer of the aminopropyl group from decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine to the aminopropyl side of spermidine (Fig. 1a). Therefore, we hypothesized that N-propyl-1,4-diaminobutane, namely, N-propylated putrescine, is a potential inhibitor of ACL5 because of the loss of amino group, which is required for the transfer of the aminopropyl group in thermospermine biosynthesis. We designed a synthetic scheme and successfully synthesized this compound by Ns-strategy24, in which 2-nitrobenzenesulfonamide (Ns) is used for both protecting and activating the group (see Methods). We named the compound as xylemin after its xylem-inducing activity, which is described below in detail.

To examine the effect of xylemin on the biosynthesis of thermospermine, wild-type seedlings were incubated for 24 hours with 30 μM xylemin and 10 μM spermidine. The level of thermospermine was drastically reduced in these seedlings compared with that of the seedlings incubated only with spermidine (Fig. 1b). However, the level of spermine was not significantly reduced in the seedlings treated simultaneously with xylemin and spermidine (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, while wild-type seedlings treated for 24 hours with 30 μM xylemin showed no reduction in the endogenous levels of both spermine and thermospermine, those grown for 10 days with xylemin showed significantly reduced levels of thermospermine (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Next, we examined the effect of xylemin on xylem differentiation. When grown with different concentrations of xylemin, wild-type seedlings showed obvious enhancement of xylem vessel differentiation in the hypocotyl at concentrations greater than 30 μM (Fig. 1c). We detected the enhancement of xylem differentiation only 12 hours after application of xylemin (Supplementary Fig. S2). Furthermore, daily application of xylemin to the shoot apex of wild-type seedlings remarkably repressed stem growth while resulting in excess xylem differentiation in stem internodes (Fig. 1d). Xylemin did not affect stem growth and xylem differentiation in acl5-1 (Fig. 1d).

To examine the effect of xylemin on gene expression, 7-day-old seedlings were treated with xylemin for 2 or 24 hours. Transcript levels of ACL5 and SAMDC4 were strongly increased by xylemin (Fig. 1e). SAMDC4 encodes an S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase that donates an aminopropyl group specifically for thermospermine synthesis and its expression is up-regulated in acl5-1 and down-regulated by exogenous thermospermine13,19. Expression of spermine synthase (SPMS) was slightly increased by xylemin treatment (Fig. 1e). We also examined expression of the genes involved in the regulation of vascular differentiation. ATHB8 is known to function redundantly with other HD-ZIP III members in vascular development22,23. MONOPTEROS (MP) is an auxin-responsive transcription factor (ARF5) that mediates auxin-induced procambium formation25,26. MP directly induces ATHB8 expression at preprocambial stages23. Transcript levels of these genes are increased in acl5-119. These genes were also up-regulated by xylemin (Fig. 1e). In addition, expression of an auxin biosynthetic gene YUCCA2 (YUC2) was also increased by xylemin treatment. When wild-type seedlings were grown for 7 days with different concentrations of xylemin, the transcript level of ACL5 was increased with 10 μM or more xylemin, but transcription levels of SPMS were not altered (Fig. 1f). These results indicate that xylemin affects the feedback regulation of polyamine biosynthetic genes and promotes expression of key regulators involved in vascular development.

Thermospermine suppresses the effect of xylemin on xylem differentiation

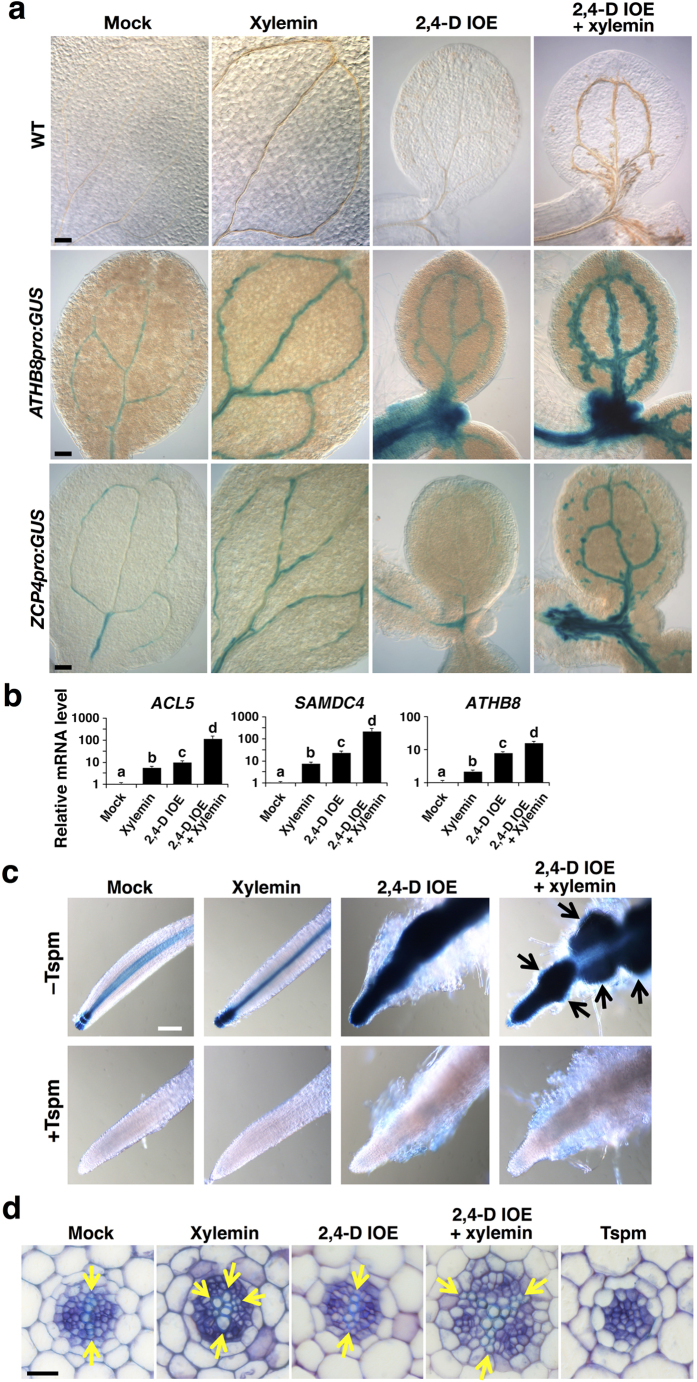

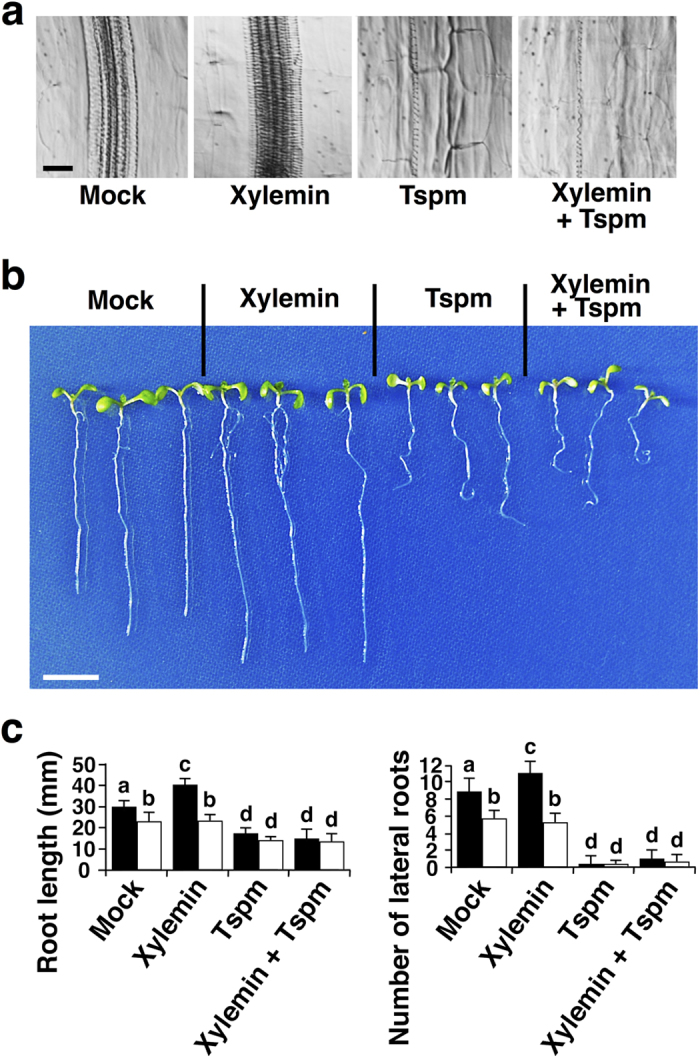

To determine whether the effect of xylemin is negated by thermospermine, thermospermine was simultaneously added with xylemin to the liquid medium. Exogenous addition of thermospermine significantly suppressed xylemin-inducible xylem differentiation (Fig. 2a). We also examined the effect of xylemin and thermospermine on root growth. Xylemin promoted main root growth and lateral root formation in the wild type but not in acl5-1, whereas thermospermine suppressed them in both seedlings (Fig. 2b,c).

Figure 2. Thermospermine suppresses effect of xylemin on xylem differentiation and root growth.

(a) Effect of xylemin and thermospermine (Tspm) on xylem differentiation in hypocotyls. The wild-type seedlings were germinated and grown for 7 days in the liquid medium without (Mock) or with 50 μM xylemin and/or 100 μM thermospermine (Tspm). Scale bar: 20 μm. (b) Effect of xylemin and thermospermine (Tspm) on seedling development. The wild-type seedlings were grown as in (a). Scale bar: 1 cm. (c) Quantification of main root growth (left panel) and lateral root formation (right panel). Black and white bars indicate wild type and acl5-1, respectively. Data are displayed as averages ± SD (n = 10 plants). Different letters indicate significantly different values from each other (Student t-test, P < 0.01).

A proauxin remarkably enhances the inductive effect of xylemin on xylem differentiation

We next investigated whether or not the synthetic auxin prodrug 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid isooctyl ester (2,4-D IOE) enhances xylem differentiation in xylemin-treated plants similarly to the acl5-1 mutant17,18. Xylemin promoted xylem vessel differentiation in wild-type cotyledons, whereas 2,4-D IOE alone did not, although 2,4-D IOE treatment affected cotyledon expansion (Fig. 3a). The growth of wild-type seedlings in the presence of both 2,4-D IOE and xylemin strongly enhanced the effect of xylemin on xylem vessel differentiation (Fig. 3a). The effect of 2,4-D IOE was also confirmed by the expression of the GUS reporter gene fused to the ATHB8 promoter (ATHB8pro:GUS). Xylemin treatment enhanced ATHB8pro:GUS expression in veins (Fig. 3a). Because ATHB8 expression is auxin-responsive, 2,4-D IOE solely induced ATHB8pro:GUS expression, especially in hypocotyls. Simultaneous addition of xylemin and 2,4-D IOE synergistically enhanced ATHB8pro:GUS expression around veins (Fig. 3a). The synergistic effect of xylemin and 2,4-D IOE was also observed by the expression of a xylem vessel-specific marker, Zinnia Cysteine Protease 4 (ZCP4pro:GUS), which was not up-regulated solely by 2,4-D IOE (Fig. 3a). We further examined the effect of 2,4-D IOE and xylemin on gene expression and found that the transcript levels of ACL5, SAMDC4, and ATHB8 were increased by about 100-fold by the co-treatment with xylemin and 2,4-D IOE (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Auxin enhances inductive effect of xylemin on xylem differentiation.

(a) Effect of xylemin and 2,4-D IOE (auxin prodrug) on xylem differentiation in the wild type (upper panels) and on expression pattern of ATHB8pro:GUS (middle panels) and ZCP4pro:GUS (lower panels). The wild-type, ATHB8pro:GUS, or ZCP4pro:GUS seedlings were germinated and grown for 7 days in the liquid medium without (Mock) or with 50 μM xylemin and/or 3 μM 2,4-D IOE. Scale bars: 100 μm. (b) Effect of xylemin and 2,4-D IOE on gene expression. Total RNA was isolated from the wild type seedlings germinated and grown for 7 days in the liquid medium without (Mock) or with 50 μM xylemin and/or 3 μM 2,4-D IOE. All transcript levels are relative to those in mock-treated seedlings. Data are displayed as averages ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate Tukey’s HSD groupings (P < 0.05). (c) Effect of xylemin, thermospermine (Tspm), and 2,4-D IOE on expression of ATHB8pro:GUS in roots. The ATHB8pro:GUS seedlings were germinated and grown for 7 days in the liquid medium without (Mock) or with 50 μM xylemin, 3 μM 2,4-D IOE, and/or 100 μM thermospermine (Tspm). Arrows indicate induction and fasciation of lateral roots. Scale bar: 100 μm. (d) Effect of xylemin, thermospermine (Tspm), and 2,4-D IOE on xylem differentiation in roots. The wild type seedlings were germinated and grown for 7 days in the liquid medium without (Mock) or with 50 μM xylemin (Xylemin), 3 μM 2,4-D IOE (2,4-D IOE), 50 μM xylemin plus 3 μM 2,4-D IOE (Xylemin +2,4-D IOE), or 100 μM thermospermine (Tspm). Arrows indicate xylem vessel elements. Scale bar: 20 μm.

The effects of xylemin, thermospermine, and 2,4-D IOE were also examined in root tissue. Xylemin promoted xylem differentiation in the root, whereas thermospermine almost completely blocked it (Fig. 3c,d). Excess xylem formation in xylemin-treated wild-type roots was reminiscent of that of untreated acl5-1 (Supplementary Fig. S3). Xylemin and 2,4-D IOE synergistically promoted xylem formation (Fig. 3c,d). The roots treated with xylemin showed stronger ATHB8pro:GUS expression compared to that untreated, whereas the roots treated with 2,4-D IOE showed much stronger GUS staining associated with callus formation (Fig. 3c). Co-treatment with 2,4-D IOE and xylemin resulted in the disorder of cell files, probably indicating enhanced induction and fasciation of lateral roots (Fig. 3c). When thermospermine was added simultaneously with xylemin and/or 2,4-D IOE, neither GUS staining nor the disorder of cell files was observed (Fig. 3c). These results appear to be consistent with the contrasting functions of thermospermine and auxin in xylem differentiation and lateral root formation, and that xylemin is an inhibitor of thermospermine biosynthesis.

Our previous study has identified suppressor mutants of acl5-1, named sac, which recover the dwarf phenotype in the absence of thermospermine. SAC51 encodes a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) protein whose translation is enhanced by thermospermine and may play a key role in thermospermine-dependent suppression of xylem differentiation27,28. In the sac51-d dominant allele, SAC51 translation may occur independent of the control by thermospermine. Thus, we examined the effect of xylemin in sac51-d and confirmed that xylem differentiation was not enhanced by xylemin in sac51-d (Supplementary Fig. S4). In addition, xylemin did not affect xylem differentiation in acl5-1 (Supplementary Fig. S4). In contrast to the wild type, sac51-d was also not responsive to xylemin in the transcript levels of ACL5, SAMDC4, and ATHB8 (Supplementary Fig. S5). These results suggest that the effect of xylemin on xylem differentiation is mediated by its effect on thermospermine-dependent expression of the SAC51 function.

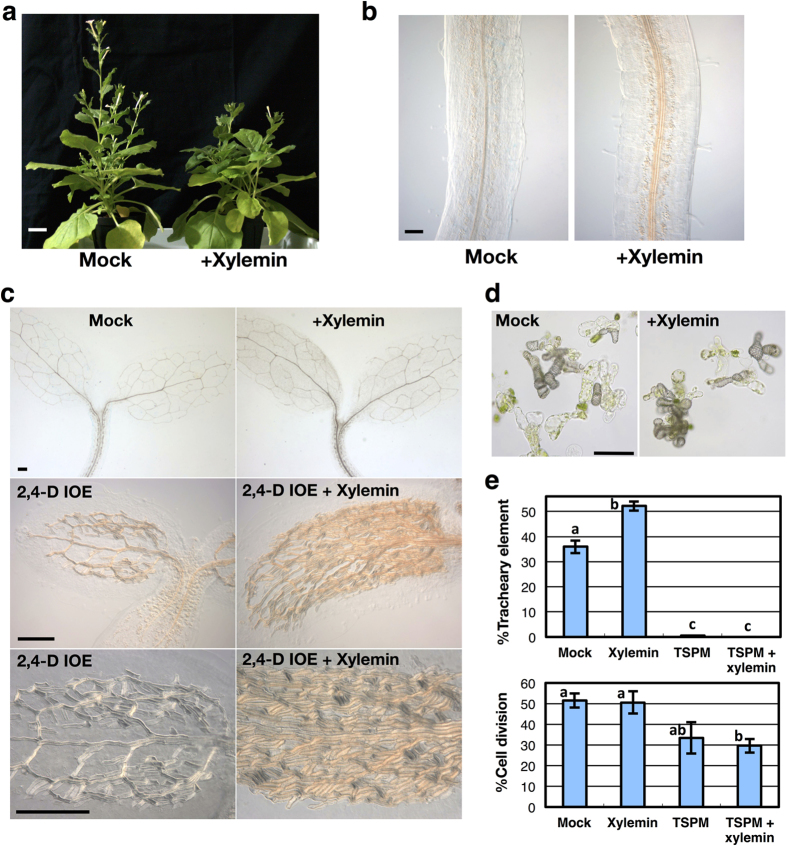

Xylemin induces xylem differentiation in other plants

To test whether xylemin can be used for elucidating the functions of thermospermine and for inducing excessive xylem formation in other plants, we examined the effect of co-treatment with xylemin and 2,4-D IOE on the stem growth and xylem differentiation in Nicotiana benthamiana. Exogenously supplied xylemin remarkably suppressed stem elongation but enhanced xylem differentiation in N. benthamiana (Fig. 4a,b). Interestingly, simultaneous addition of xylemin and 2,4-D IOE strongly and ectopically induced xylem differentiation. This effect was especially remarkable in the cotyledons. Most mesophyll cells appeared to differentiate into xylem vessel cells, by which almost the entire cotyledon was covered (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4. Xylemin remarkably promotes xylem differentiation in tobacco and zinnia.

(a) Effect of xylemin on stem elongation of N. benthamiana. Xylemin solution at the concentration of 100 μM was daily applied to the shoot apex of N. benthamiana. Scale bar: 3 cm. (b) Effect of xylemin on xylem differentiation in hypocotyls of N. benthamiana. Seedlings of N. benthamiana were germinated and grown for 7 days in the liquid medium without (Mock) or with 50 μM xylemin (+Xylemin). Scale bar: 200 μm. (c) Effect of xylemin and 2,4-D IOE on xylem differentiation in cotyledons of N. benthamiana. Seedlings of N. benthamiana were germinated and grown for 7 days in the liquid medium without (Mock) or with 50 μM xylemin and/or 3 μM 2,4-D IOE. Scale bars: 200 μm. (d) Effect of xylemin on xylem differentiation in zinnia xylogenic culture. Isolated zinnia mesophyll cells were cultured in the differentiation medium without (Mock) or with 3 μM xylemin (+Xylemin) for 4 days. Scale bar: 100 μm. (e) Quantification of tracheary element differentiation and cell division in zinnia xylogenic culture. Isolated zinnia mesophyll cells were cultured in the differentiation medium without (Mock) or with 3 μM xylemin and/or 10 μM thermospermine (Tspm) for 4 days. Data are displayed as averages ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate Tukey’s HSD groupings (P < 0.05).

Finally, we examined the effect of xylemin on xylogenic culture of Zinnia elegans. Isolated mesophyll cells of Z. elegans transdifferentiate into tracheary elements in the presence of auxin and cytokinin29. Xylemin treatment promoted tracheary element differentiation of Z. elegans, whereas thermospermine almost completely blocked it (Fig. 4d,e). Thermospermine also repressed cell division in the zinnia xylogenic culture (Fig. 4e), which is consistent with its negative effect on callus and lateral root formation (Fig. 2c). Therefore, thermospermine might negatively regulate cell division in the procambium/cambium and pericycle. These results support the notion that thermospermine-mediated suppression of auxin-inducible xylem differentiation is a universal mechanism for the regulation of xylem development in plants (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Discussion

In this study, we developed xylemin as an inhibitor of thermospermine biosynthesis and showed that it can act as a strong inducer of xylem differentiation. Although xylemin might also slightly affect spermine biosynthesis and SPMS expression, we consider that this minor effect may not contribute to the manifested phenotype because spermine-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis show normal morphology and viability16. Expanding our previous finding that 2,4-D IOE enhances xylem differentiation in acl5-1, we found here that concomitant treatment with xylemin and 2,4-D IOE has a potent and synergistic inductive effect on xylem differentiation at least in dicotyledonous plants. The findings of this study further suggest that lateral root development and procambium/cambium formation also involve a feedback control mechanism in which auxin and thermospermine play opposing roles. Together with previous findings, we propose a model of the action of xylemin in auxin-triggered xylem differentiation (Supplementary Fig. S6). Auxin promotes xylem differentiation via the MP-ATHB8 pathway23 and ATHB8 promotes ACL5 expression20, resulting in the accumulation of thermospermine, which activates SAC51 translation. Recent studies have shown that SAC51 interacts with a bHLH transcription factor, LONESOME HIGHWAY (LHW)30, whereas LHW interacts with another bHLH transcription factor TARGET OF MP5 (TMO5) to promote both vascular differentiation and ACL5 expression31,32, suggesting an antagonistic effect of SAC51 on LHW-TMO5 heterodimerization. Because LHW is required for correct expression patterns of MP and ATHB833, the LHW-SAC51 heterodimer might also directly or indirectly regulate these expression patterns in a feedback manner. Thereby, xylemin represses SAC51 translation by inhibiting thermospermine synthesis.

In the auxin canalization process, auxin accumulation enhances auxin transport, which in turn facilitates auxin accumulation into the cell34,35. This positive feedback loop generates directional and active flows of auxin molecules that determine the spatial pattern of vascular differentiation along the paths of auxin flow. Although the auxin canalization theory has been widely accepted as the primary mechanism for vascular pattern formation, it requires a pre-existing auxin source and some additional conditions or factors to form the closed vascular loops commonly found in leaf veins34,35,36. Thermospermine may be one of these factors. Because vascular tissues, especially xylem tissues, are enlarged in acl5-1 and xylemin-treated wild-type plants (Figs 1 and 3), thermospermine function appears to narrow the auxin flow by generating an inhibitory field around it and limiting the zone of vascular cell differentiation. The dwarf phenotype of acl5-1 and the phenocopy observed in xylemin-treated wild-type plants also suggest that the balance between differentiation of xylem vessel elements, which are eventually non-growing dead cells, and that of parenchymal tissues, is critical for organ elongation. Finally, our findings suggest that thermospermine is a major suppressor of xylem differentiation, which almost completely suppresses xylem formation in various organs and tissues. This is in contrast to the local effect of cytokinin on protoxylem specification in roots37,38 and the modest effect of the peptide hormone Tracheary element Differentiation Inhibitory Factor (TDIF) on xylem differentiation in roots and leaf veins39,40. Functional relationships between thermospermine and these local factors remain to be elucidated.

Manipulation of xylem differentiation is an important aspect of woody biomass production. Our findings suggest a significant possibility that xylemin and 2,4-D IOE can be applied to control woody biomass production without transgenic technology. Because thermospermine is present not only in vascular plants but also in nonvascular plants and some bacteria, xylemin is also expected to provide a useful tool for addressing physiological functions of thermospermine in these organisms.

Methods

Chemicals

Thermospermine was provided by Prof. Masaru Niitsu (Josai University). 2,4-D IOE was synthesized according to ref. 41 and provided by Prof. Kenichiro Hayashi (Okayama University of Science). 2,4-D IOE was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and polyamines were dissolved in the sterilized water. They were adjusted so that the final concentration of DMSO in each medium was less than 0.1%. All other chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com).

Synthesis of xylemin

Xylemin (1, N-propylated putrescine) was synthesized by a four-step sequence from N-(2-Ns)-1,4-diaminobutane (2, Tokyo Chemical Industry, http://www.tcichemicals.com/en/jp/index.html) as a starting material (Supplementary Fig. S7). Thus, treatment of 2 with Boc2O/Et3N gave carbamate 3 in 98% yield. Selective alkylation of 3 was carried out with 1-bromopropane in the presence of Cs2CO3/TBAI to provide the desired propylated product 4. The Ns group of 4 was removed with PhSH/Cs2CO3 to afford amine 5. Finally, deprotection of the Boc moiety of 5 with SOCl2 proceeded smoothly to produce the desired xylemin (1). The purity (>95%) of the synthesized xylemin (1) was confirmed by its 1H NMR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. S8). The 1H NMR data of xylemin (1) were shown as followings: 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 3.10–3.00 (m, 6 H), 1.77–1.65 (m, 6 H), 0.98 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3 H).

Plant materials and growth condition

The acl5-1 and sac51-d mutants were previously described14,27. ATHB8:GUS line was described in ref. 42 and provided by the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC). ZCP4:GUS line was described in ref. 43 and provided by Prof. Hiroo Fukuda (Tokyo University). Plants were grown at 22 °C in the modified Murashige-Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with 1% sucrose under continuous white light as described17,44. The liquid MS medium was used unless otherwise described. For the treatment with polyamines and/or 2,4-D IOE, 500 μl of MS liquid medium supplemented with polyamines and/or 2,4-D IOE was prepared in 24-well plates, and five to ten surface-sterilized Arabidopsis seeds (Columbia-0 accession) were spotted in each well, grown at 22 °C, and observed at the 7th day after germination for xylem vessel differentiation. Same liquid culture method was applied to N. benthamiana. For the experiment using MS agar medium, wild type Arabidopsis seeds (Columbia-0 accession) were spotted and grown on the MS medium that is supplemented with xylemin and/or thermospermine and solidified with 1% agar. For daily application of xylemin, 10–50 μL of 100 μM xylemin was added on the shoot apex of wild type Arabidopsis (Landsberg erecta accession) and N. benthamiana. Zinnia xylogenic culture was conducted according to ref. 29. The frequencies of tracheary element differentiation and cell division were calculated as the proportions of tracheary elements and divided cells to the number of living cells plus tracheary elements, respectively. The number of cells was counted in three biological replicates under a microscope (at least 500 cells were counted for each sample).

Histology and microscopy

Seedlings were fixed in a 9:1 mixture of ethanol and acetic acid. Fixed samples were then cleared in a mixture of chloral hydrate, glycerol, and water solution (8 g : 1 ml : 2 ml) and observed under a differential interference contrast microscope (DM5000B, Leica, http://www.leica-microsystems.com) equipped with a CCD camera (DFC500, Leica). Root tissues were observed under a stereomicroscope (S8APO, Leica) equipped with a CCD camera (EC3, Leica). The seedlings of ATHB8:GUS and ZCP4:GUS were permeabilized by 90% acetone. Fixed samples were then incubated with a staining solution (0.5 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3indolyl-β-Gluc, 5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6], 5 mM K4[Fe(CN)6], 0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2)) for 12 h and observed under the above mentioned light microscope or stereomicroscope. Cotyledons, hypocotyls, and GUS-stained seedlings were also observed under a light microscope (SMZ-ZT-1, Nikon, http://www.nikon-instruments.jp/jpn/index.html) equipped with a CCD camera (DS-L1, Nikon). Samples for cross section observation were fixed in FAA (45% ethanol, 5% formaldehyde, 5% acetic acid), dehydrated through an ethanol series, and embedded in Technovit 7100 resin (Heraeus Kulzer, www.heraeus-kulzer.com/). Samples were sectioned into 10-μm-thick slices by a rotary microtome (RM2245, Leica) equipped with a tungsten carbide disposable blade (TC65, Leica). Sections were stained with 0.1% Toluidine blue and observed under the light microscope (DM5000B). Inflorescence stems from one-month-old plants were embedded in 4% agar, sectioned by a vibrating blade microtome (MicroSlicer ZERO-1, D.S.K, http://www.dosaka-em.jp/), stained with phloroglucinol-HCl (1% phloroglucinol in 6 M HCl) and observed under the light microscope (DM5000B).

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from whole seedlings grown in the liquid medium for 7 days by phenol/chloroform extraction and subsequent lithium chloride precipitation as described45. For each sample, 30 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using ReverTra Ace reverse transcriptase (TOYOBO, http://www.toyobo.co.jp) according to the accompanying protocol. Real-time PCR was performed in a DNA Engine Opticon2 System (Bio-Rad, http://www3.bio-rad.com) using KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Kit (KAPA Biosystems, https://www.kapabiosystems.com) and gene-specific primers; 5′-ACCGT TAACC AGCGA TGCTT T-3′ and 5′-CCGTT AACTC TCTCT TTGAT TCTTC GATCC-3′ for ACL5, 5′-ATGGC AGTGT CTGGG TTCGA-3′ and 5′-CTATT TCCGA CGAGG CGTGA-3′ for SAMDC4, 5′-ACATA TCCAA GCGGC GTGAT-3′ and 5′-CCTCT TCAAG AGTTC TACAA AG-3′ for SPMS, 5′-AGCGT TTCAG CTAGC TTTTG AG-3′ and 5′-CAGTT GAGGA ACATG AAGCA GA-3′ for ATHB8, 5′-GATGA TCCAT GGGAA GAGTT-3′ and 5′-TAAGA TCGTT AATGC CTGCG-3′ for MP, 5′-ATGTG GCTAA AGGGA GTGAA-3′ and 5′-AACTT GCCAA ATCGA AACCC-3′ for YUC2, and 5′-GTGAG CCAGA TCTTC ATTCG TC-3′ and 5′-TCTCT TGCTC GTAGT CGACA G-3′ for ACTIN8 (ACT8), according to ref. 19. Transcript levels of ACT8 were used as a reference for normalization. The RT-qPCR were performed using at least three biological replicates.

HPLC analysis

Polyamines were extracted from seedlings in 5% perchloric acid. Polyamine standards and plant samples were benzoylated according to ref. 46. The resulting samples were injected into a reverse-phase column (TSK-gel ODS-100V, 5 μm, 2.0 × 150 mm, Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan) and eluted with 42% (v/v) acetonitrile at a flow-rate of 0.2 mL/min for 30 min using the Agilent 1120 Compact LC. The benzoyl polyamines were detected at 254 nm. HPLC analyses were conducted in three biological replicates.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yoshimoto, K. et al. Chemical control of xylem differentiation by thermospermine, xylemin, and auxin. Sci. Rep. 6, 21487; doi: 10.1038/srep21487 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Masaru Niitsu (Josai University) for thermospermine, Prof. Kenichiro Hayashi (Okayama University of Science) for 2,4-D IOE, ABRC for Arabidopsis seeds, and Prof. Hiroo Fukuda (Tokyo Univ.) for ZCP4pro:GUS seeds. This work is supported by the grant-in-aids from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 22370021, 23119513, 25119715, 25440137, 26113516) and Ryobi Teien Memory Foundation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions K.Y., H.T., I.K., H.M. and T.T. designed the research, interpreted the data and wrote the paper. K.Y., H.T., H.M. and T.T. performed experiments.

References

- Igarashi K. & Kashiwagi K. Modulation of cellular function by polyamines. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 39–51 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegg A. E. & Casero R. A. Current status of the polyamine research field. Methods Mol. Biol. 720, 3–35 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuell C., Elliott K. A., Hanfrey C. C., Franceschetti M. & Michael A. J. Polyamine biosynthetic diversity in plants and algae. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48, 513–520 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagni N. & Tassoni A. Biosynthesis, oxidation and conjugation of aliphatic polyamines in higher plants. Amino Acids 20, 301–317 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano T., Berberich T., Tateda C. & Takahashi Y. Polyamines: essential factors for growth and survival. Planta 228, 367–381 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. & Kakehi J. Polyamines: ubiquitous polycations with unique roles in growth and stress responses. Ann. Bot. 105, 1–6 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschou P. N. et al. The polyamines and their catabolic products are significant players in the turnover of nitrogenous molecules in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 5003–5015 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiburcio A. F., Altabella T., Bitrian M. & Alcazar R. The roles of polyamines during the lifespan of plants: from development to stress. Planta 240, 1–18 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima T. A new polyamine, thermospermine, 1,12-diamino-4,8-diazadodecane, from an extreme thermophile. J Biol. Chem. 254, 8720–8722 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minguet E. G., Vera-Sirera F., Marina A., Carbonell J. & Blázquez M. A. Evolutionary diversification in polyamine biosynthesis. Mol Biol Evol. 25, 2119–2128 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano A., Kakehi J. & Takahashi T. Thermospermine is not a minor polyamine in the plant kingdom. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 606–616 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott J. M., Römer P. & Sumper M. Putative spermine synthases from Thalassiosira pseudonana and Arabidopsis thaliana synthesize thermospermine rather than spermine. FEBS Lett. 581, 3081–3086 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehi J., Kuwashiro Y., Niitsu M. & Takahashi T. Thermospermine is required for stem elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 49, 1342–1349 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa Y., Takahashi T. & Komeda Y. ACL5: an Arabidopsis gene required for internodal elongation after flowering. Plant J. 12, 863–874 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzawa Y. et al. ACAULIS5, an Arabidopsis gene required for stem elongation, encodes a spermine synthase. EMBO J. 19, 4248–4256 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai A. et al. Spermine is not essential for survival of Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 556, 148–152 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto K. et al. A chemical biology approach reveals an opposite action between thermospermine and auxin in xylem development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 635–645 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto K. et al. Thermospermine suppresses auxin-inducible xylem differentiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal Behav. 7, 937–939 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong W. et al. Thermospermine modulates expression of auxin-related genes in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 5, 94 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baima S. et al. Negative feedback regulation of auxin signaling by ATHB8/ACL5–BUD2 transcription module. Mol. Plant 7, 1006–1025 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milhinhos A. et al. Thermospermine levels are controlled by an auxin-dependent feedback loop mechanism in Populus xylem. Plant J. 75, 685–698 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsbecker A. et al. Cell signalling by microRNA165/6 directs gene dose-dependent root cell fate. Nature 465, 316–321 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner T., Sherr I. & Scarpella E. Regulation of preprocambial cell state acquisition by auxin signaling in Arabidopsis leaves. Development 136, 3235–3246 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan T. & Fukuyama T. Ns strategies: a highly versatile synthetic method for amines. Chem. Commun. 21, 353–359 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przemeck G. K., Mattsson J., Hardtke C. S., Sung Z. R. & Berleth T. Studies on the role of the Arabidopsis gene MONOPTEROS in vascular development and plant cell axialization. Planta 200, 229–237 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardtke C. S. & Berleth T. The Arabidopsis gene MONOPTEROS encodes a transcription factor mediating embryo axis formation and vascular development. EMBO J. 17, 1405–1411 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai A. et al. The dwarf phenotype of the Arabidopsis acl5 mutant is suppressed by a mutation in an upstream ORF of a bHLH gene. Development 133, 3575–3585 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehi J. et al. Mutations in ribosomal proteins, RPL4 and RACK1, suppress the phenotype of a thermospermine-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One 10, e0117309 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda H. & Komamine A. Establishment of an experimental system for the study of tracheary element differentiation from single cells isolated from the mesophyll of Zinnia elegans. Plant Physiol. 65, 57–60 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rybel B. et al. A bHLH complex controls embryonic vascular tissue establishment and indeterminate growth in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 24, 426–437 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Sirera F. et al. A bHLH-based feedback loop restricts vascular cell proliferation in plants. Dev. Cell 35, 432–443 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama H. et al. A negative feedback loop controlling bHLH complexes is involved in vascular cell division and differentiation in the root apical meristem. Curr. Biol 25, 3144–3150 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi-Ito K., Oguchi M., Kojima M., Sakakibara H. & Fukuda H. Auxin-associated initiation of vascular cell differentiation by LONESOME HIGHWAY. Development 140, 765–769 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs T. Cell polarity and tissue patterning in plants. Development Suppl. 1, 83–93 (1991).1769343 [Google Scholar]

- Scarpella E., Marcos D., Friml J. & Berleth T. Control of leaf vascular patterning by polar auxin transport. Genes Dev. 20, 1015–1027 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feugier F. G. & Iwasa Y. How canalization can make loops: A new model of reticulated leaf vascular pattern formation. J. Theor. Biol. 243, 235–244 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mähönen A. P. et al. Cytokinin signaling and its inhibitor AHP6 regulate cell fate during vascular development. Science 311, 94–98 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishopp A. et al. A mutually inhibitory interaction between auxin and cytokinin specifies vascular pattern in roots. Curr. Biol. 21, 917–926 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa Y., Kondo Y. & Fukuda H. TDIF peptide signaling regulates vascular stem cell proliferation via the WOX4 homeobox gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22, 2618–2629 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y. et al. Plant GSK3 proteins regulate xylem cell differentiation downstream of TDIF-TDR signalling. Nat. Commun. 24, 3504 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K. et al. Auxin transport sites are visualized in planta using fluorescent auxin analogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 11557–11562 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baima S. et al. The expression of the Athb-8 homeobox gene is restricted to provascular cells in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 121, 4171–4182 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyo H., Demura T. & Fukuda H. Spatial and temporal tracing of vessel differentiation in young Arabidopsis seedlings by the expression of an immature tracheary element-specific promoter. Plant Cell Physiol. 45, 1529–1536 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takatani S., Hirayama T., Hashimoto T., Takahashi T. & Motose H. Abscisic acid induces ectopic outgrowth in epidermal cells through cortical microtubule reorganization in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci Rep. 5, 11364 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T., Naito S. & Komeda Y. Isolation and analysis of the expression of two genes for the 81-kilodalton heat-shock proteins from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 99, 383–390 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka Y. et al. Quantitative analysis of plant polyamines including thermospermine during growth and salinity stress. Plant Physiol Biochem. 48, 527–533 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.