Abstract

Quantitative magnetization transfer (qMT) imaging in skeletal muscle may be confounded by intramuscular adipose components, low signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs), and voluntary and involuntary motion artifacts. Collectively, these issues could create bias and error in parameter fitting. In this study, technical considerations related these factors were systematically investigated and solutions were proposed. First, numerical simulations indicate that the presence of an additional fat component significantly underestimates the pool size ratio (F). Therefore, fat-signal suppression (or water-selective excitation) is recommended for qMT imaging of skeletal muscle. Second, to minimize the effect of motion and muscle contraction artifacts in datasets collected with a conventional 14-point sampling scheme, a rapid two-parameter model was adapted from previous studies in the brain and spinal cord. The consecutive pair of sampling points with highest accuracy and precision for estimating F was determined with numerical simulations. Its performance with respect to SNR and incorrect parameter assumptions was systematically evaluated. QMT data fitting was performed in healthy control subjects and polymyositis patients, using both the two- and five-parameter models. The experimental results were consistent with the predictions from the numerical simulations. These data support the use of the two-parameter modeling approach for qMT imaging of skeletal muscle as a means to reduce total imaging time and/or permit additional signal averaging.

Keywords: Inflammatory myopathies, polymyositis, muscle disease, quantitative magnetization transfer, MRI, biomarker

Introduction

Quantitative magnetization transfer (qMT) MRI (1) has been developed to characterize the spatial distribution of the relative contents of the macromolecular and free water proton pools of biological tissues. Specifically, qMT MRI fits appropriately acquired MRI data to a two-pool model of magnetization exchange between macromolecules and protons, providing estimates of the relaxation and exchange rates of macromolecular and free water protons as well as the ratio of the sizes of these two pools (the pool size ratio, PSR). A number of different approaches have been developed for acquiring and analyzing qMT MRI data, including continuous-wave (CW) saturation (1), pulsed saturation (2-4), selective inversion recovery (SIR) (5-7), and stimulated echo (8) methods. Though there has been no quantitative comparison of all these methods, the pulsed saturation method is the most widely adopted method, and various strategies for rapid qMT imaging have been developed (9-11).

Several studies have demonstrated the potential clinical and translational value of qMT. For example, the PSR is correlated with myelin content in white matter (9,12). QMT studies have also been performed in healthy skeletal muscles (13-15) and in a murine model of inflammation (16). It was demonstrated that PSR may also serve as a biomarker of inflammation (16). However, quantitative MRI studies in skeletal muscle are challenged by low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), caused by the short T2 values of water protons (~30 ms at 3.0T), as well as static (B0) and radiofrequency transmit (B1+) field inhomogeneities (15). In a number of muscle diseases, fat infiltration is a major pathological component. It is possible that this third pool of protons, if unaccounted for quantitatively, would also confound qMT parameter estimations.

Another potential confounding factor for qMT in muscle is related to the large number of data points required to fit a full model. As noted previously (15), voluntary and involuntary motion artifacts can occur during data collection (~10 min for a full dataset). These movements can result from gross subject movements, prolonged muscle contraction, and/or brief twitches. For translational and rotational bulk motions, image registration can be performed using a rigid-body registration algorithm. However, muscle contractions induce non-rigid deformations as well, making it challenging to register such images. More seriously, motion during the data collection process may introduce artifacts in the images that cannot be corrected using registration methods, and the parameter estimates may be biased as a result. To mitigate issues such as these, a two-point sampling approach was recently described for qMT studies of the brain and spinal cord (10,11). In this approach, values are assumed for model parameters that do not undergo substantial biological variation or to which the model is relatively insensitive. By reducing the number of unknowns in the model, a reduced data sampling approach can be used and iterative curve-fitting is obviated.

The overall goals of this work were to 1) determine the quantitative effects of these sources of error and 2) propose and test strategies for reducing these errors. First, we investigated the effect of an additional fat component in pulsed-MT parameter fitting through numerical simulations. It was found that PSR would be underestimated in the presence of an additional fat component. For in vivo qMT image data collection in healthy controls and patients, a 1-3-3-1 binomial water selective excitation pulse was then used to minimize the fat signal contribution to the qMT data. Second, to minimize motion artifact-induced bias in parameter fitting, the two-point fitting approach (10,11) was adopted and applied to a set of data acquired with a conventional 14-point sampling scheme. Although this method has been previously applied in the central nervous system, muscle has significantly different MT and relaxation parameters compared to those in brain and spinal cord. A combination of numerical simulations and in vivo data indicated that the two-point scheme is more robust at low SNR levels, with the capability to minimize the occurrence and effects of motion artifacts and reduce total acquisition time.

Theory

Pulsed-MT model

All simulations and data processing are based on the model proposed by Ramani et al. (17). For a two-pool exchange system, which includes the free water pool (A) and the macromolecular pool (B), the signal equation is written as (18):

| (1) |

where SqmT is the observed MT-weighted signal; S0 is the observed signal without the saturation pulse; is the exchange rate from the macromolecular pool to the free water pool; F is the PSR, defined as ; RA is the longitudinal relaxation rate of the water pool; and are the transverse relaxation time constants of the macromolecular and free water pools, respectively; RB is the longitudinal relaxation rate constant of the macromolecular pool; RRFB is the rate constant for saturation of longitudinal magnetization of the macromolecular pool. It is noted that RB is often assumed to be 1.0 s−1 due to the weak dependence of the measured signals on this parameter (1). For in vivo tissue, a super-Lorentzian lineshape (19) is often adopted for calculating RRFB:

| (2) |

The average power, ωCWPE, is calculated as:

| (3) |

where τ is the saturation pulse width and TR is the repetition time of the pulse train. The fitted qMT parameters are: and . In addition, RA is calculated from an independent estimate of the observed R1 of the free water pool, noted as RAOBS (17):

| (4) |

A full pulsed-MT protocol thus includes four sets of measurements: T1 mapping for RAOBS, B1+ mapping to correct the irradiation power, B0 mapping to correct the RF frequency offsets, and the pulsed saturation data collection.

Pulsed-MT model with an additional fat component

A study at 7.05 T (20) showed that when a system containing an additional fat component is irradiated using an RF saturation pulse having a frequency offset of >4 ppm from water, the saturation effect on the fat protons can be ignored. This is because fat protons have chemical shifts of less than ~3.5 ppm from water. In our pilot studies at 3.0T (details not shown), we similarly found that even for frequency offsets >2.5 ppm, the saturation effect on fat signals was < 2% over a wide range of saturation power levels. Thus for simplicity, it can be reasonably assumed that the saturation effects on fat protons are negligible. Note that in healthy muscles, the fat component fraction is usually below 0.1 (15), but for muscle disease, the fat fraction may be elevated to as much as 1.0 for completely fat replaced muscle.

Two-parameter qMT model

Based on the pulsed-Z spectroscopic model (4), single-offset pulsed saturation approaches (10,11) was recently proposed. In these approaches, three parameters are held constant during the fitting process: , , and . It has been demonstrated that the fast exchange rate, , is insensitive to pathophysiological changes and can thus be assumed to be a constant (9,21). It was also found that varies little across white matter and gray matter in healthy human brain and multiple sclerosis lesions, and can be assumed as a constant (3,22). Finally, although RA and may vary significantly, the product fairly constant in both healthy and diseased tissues (22).

Based on these findings, we demonstrate that this approach can also be applied to skeletal muscle. In this case, Ramani's model (as described in Eq. [1-4]) was rearranged with these three constants (, and ) and only two parameters to be fitted, S0 and F/RA. In the special case that one of the two sampling points is at very large frequency offset, the saturation effect can also be ignored, and this signal can be used to normalize the other signal data at low frequency offset and the corresponding F/RA is written as (derivation details not shown):

| (5) |

where Sn is the normalized observed signal at the lower frequency offset. In this case, F values can be directly calculated, and the iterative fitting process is not required. If this two-parameter approach could be shown to provide estimates of the PSR that were at least as accurate as the five-parameter approach, then the time used for data acquisition could be reduced or allocated differently to improve the SNR. Also, data analysis time would be significantly reduced by obviating iterative curve-fitting.

For convenience, in the following discussion, the “five-parameter model” is used to refer the conventional presentation of Ramani's model (with a full sampling scheme) and the “two-parameter model” is used to refer to Ramani's model with three constant parameters and only two parameters to be calculated.

Materials and Methods

Numerical Simulations

All numerical simulations and data analyses were performed with scripts written in MATLAB 2013a (The MathWorks, Inc; Natick MA).

Simulation 1: Effect of an additional fat component on pulsed-qMT parameter fitting

To predict the effect of fitting qMT data to a two-pool model for a tissue that contains an additional fat component, qMT signals were generated for a model tissue. Signals were generated using a set of typical parameters (S0 = 1, , F = 0.08, , , and RAOBS= 0.7 s−1). The sampling scheme used here includes two saturations at nominal flip angles of 360° and 820° and frequency offsets of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 kHz. The fat fractions were varied between 0.01 and 0.96, stepped by 0.05. Gaussian noise was added to the generated signals to create an SNR of 100. The noisy signal data were then fitted to the five-parameter model, which does not account for the effect of fat on the observed signal. At each fat fraction, 1000 iterations were performed, each using an independent noise realization. The mean and standard deviation (SD) of the fitted qMT parameters were plotted as functions of the fat fraction and used to predict the effect of an un-modeled fat component on qMT data analysis. It will be shown that the failure to model the fat component introduces significant error into qMT parameter estimation. Therefore, Simulations 2-4 were performed without a fat component, and water-selective excitation was used in the experimental data collection.

Simulation 2: Determination of the consecutive pair of sampling points from the 14-point scheme that produces the most accurate and precise estimation of PSR using the 2-point scheme

In the experimental studies described below, the qMT data were acquired with the full 14-point scheme. The data were acquired in the order of flip angles and saturation frequency offsets presented in Table 1. When these data were analyzed using the 2-point scheme, only consecutive pairs of sampling points were examined. This was done to minimize the effects of motion artifacts. This procedure was replicated in Simulation 2.

Table 1.

Saturation flip angles and pulses offsets used in simulation and experimental studies. Data were acquired in the order (360°, 100, 1, 2...50 kHz) followed by (820°, 100, 1, 2...50 kHz). Flip angles of 360° and 820° correspond to average saturation powers of 259.1 and 590.3 rad/s, respectively.

| Saturation flip angle (°) | Saturation pulse offset (kHz) |

|---|---|

| 360 | 100, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 |

| 820 | 100, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 |

Signals were first generated with the full 14-point scheme and the five-parameter model, with the above-given parameter values. Gaussian noise was added at SNR level of 100. Then, each consecutive pair of generated signal was iteratively fitted to the two-parameter model in a least square sense, while assuming , , and . The and values were adopted from previous studies in healthy skeletal muscle (14). Compared to Simulation 2, a lower value of was used, corresponding to RA = 0.7 s−1 and . The reason for adopting a slightly higher value is that, for the pulsed-MT fitting with Ramani's model, it was found that is always overestimated (23). For each pair of sampling points, 1000 independent noise realizations were performed. The mean and SD were calculated for each pair and used to characterize the accuracy and precision of each combination.

Simulation 3: Comparison of the 2-point scheme and the 14-point scheme at different SNR levels

Simulation 2 will show that the [(820°, 100 kHz) (820°, 1 kHz)] pair of sampling points produces the most accurate and precise estimation of PSR among the 13 consecutive pairs of sampling points tested. By assuming three constants and avoiding iterative curve-fitting, high SNR robustness is anticipated for the two-point scheme. Using the same set of system parameters used in Simulation 2, data were generated using the five-parameter model for the 14-point scheme. Gaussian noise was added at SNR levels ranging from 50 to 200 at a step size of 25. The full 14-point data were then fitted to the five-parameter model. The generated data at (820°, 100 kHz) and (820°, 1 kHz) were used to solve F with the two-parameter model. At each SNR level, 1000 independent noise realizations were performed. The mean and SD were calculated for each approach and used to calculate their noise sensitivities.

Simulation 4: Evaluation of potential parameter bias when using the 2-point scheme

Although Simulation 3 will demonstrate reduced noise sensitivity with the 2-point approach, the possibility exists that incorrect assumptions would significantly bias the parameter estimates. To investigate further the potential bias originating from the assumption of the three constants, , and were uniformly randomized between 40 - 60 Hz, 4 - 8 μs, and 30 - 60 ms, respectively. Each parameter was separately varied while the other parameters were held constant at their default values. Gaussian noise at a SNR level of 100 was added to the signal; 1000 independent noise realizations were performed for each simulation. The data at (820°, 100 kHz) and (820°, 1 kHz) were used to calculate F using Eq. [4] and [6]. The mean and SD of F were then calculated.

Experimental Studies

Subjects

Two healthy subjects and two physician-diagnosed polymyositis (PM) patients were imaged. The study was approved by Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University. All subjects provided written, informed consent. All subjects adhered to 24-hour restrictions from moderate and heavy exercise, over-the-counter medication usage, and alcohol or drug use. They were positioned on the patient bed of the imager in a feet-first supine position. Images were acquired in the middle of their right thighs. Straps and supporting pads were used to fix the position of their thighs and to prevent motion. Their feet were taped together to prevent rotation.

In Vivo MRI

Data Acquisition

MRI data were acquired on a 3.0-T Philips Achieva scanner (Philips Medical Systems; Best, The Netherlands). A two-channel body coil was used for signal excitation. A six-channel sensitivity encoding (SENSE) cardiac coil was used for signal reception. All images had field-of-view of 256 × 256 mm2, 11-slice coverage, and slice thickness of 7 mm. High-resolution anatomical images were acquired using a T1-weighted sequence with a turbo-spin-echo (TSE) readout, with sequence parameters TR/TE = 530/6.2 ms, matrix size = 340× 340 with 512 × 512 reconstruction, excitation flip angle = 90°, refocusing pulse flip angle = 110°, SENSE factor = 1.4, TSE factor = 6, and number of excitations (NEX) = 1.

For qMT parameter fitting, B1+ field maps, B0 field maps, T1 maps, and pulsed-saturation qMT data were acquired. The B1+ field maps were acquired using an actual flip angle method (24), with excitation flip angle of 60°, delays of TR1/TR2 = 30/130 ms, TE = 2.2 ms, a matrix size of 64 × 64 with 128 × 128 reconstruction, and NEX =1. To avoid slice profile artifacts, 55 slices were acquired, and only the central 11 slices were kept for analysis. B0 inhomogeneities were mapped using a dual-echo gradient echo sequence (25), with TR/TE1/TE2 = 25/2.3/4.6 ms, excitation flip angle of 25°, SENSE = 1.3, and NEX = 1. T1 data were acquired using an inversion recovery pulse with turbo-field-echo (TFE) readout (26), followed by a train of saturation pulses and a reduced pre-delay (TD) of 1.5 s (27), where TD is the time from the last saturation pulse to the inversion pulse. Seven inversion-recovery time (TI) points were collected, with TI = 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000, 2000, and 6000 ms. Following from the results of Simulation 1, the signals from fat protons were minimized via a 1-3-3-1 binomial water selective excitation pulse. Pulsed saturation data were collected with a MT-weighted 3D fast-field-echo (FFE) sequence, with TR/TE = 50/3.9 ms, SENSE = 1.3, 11 slices, and NEX = 2. The MT pulses had pulse width of 20 ms, the flip angles and offset frequencies noted in Table 1, and a bandwidth of 106 Hz. To reduce T1-weighting in the qMT data, the excitation flip angle was set at 6°. The full imaging protocol took~30 minutes, including subject setup.

Data Analysis

The B1+ maps were calculated using the algorithm presented in (24). The ΔB0 maps were calculated based on the phase differences between the complex images with different echo times. T1 maps were calculated using an inversion recovery with reduced TD model (27). The pulsed saturation data were first fitted to the five-parameter model with all 14 sampling points. The data at the sampling points of (820°, 1kHz) and (820°, 100kHz) were then fitted to the two-parameter model, as described in Eq.

Error! Reference source not found.. The constants used in the two-parameter model fitting were: , , and .

To determine the qMT parameters of individual muscles, regions-of-interest (ROIs) were drawn along the border of the eight main muscle groups identified in the images. These were the rectus remoris (RF), vastus lateralis (VL), vastus intermedius (VI), vastus medialis (VM), biceps femoris (BF), semitendinosus (ST), semimembranosus (SM), and adductor magnus/longus (AD) muscle, as shown in Figure 1. The mean and SD of the pixel F values in the ROIs were then calculated and compared to the simulations’ predictions.

Figure 1.

High-resolution anatomical T1-weighted images of two healthy controls and two PM patients. The eight muscles studied in this work are labeled in the upper left panel: rectus femoris (RF), vastus lateralis (VL), vastus intermedius (VI), vastus medialis (VM), biceps femoris (BF), semitendinosus (ST), semimembranosus (SM), and adductor magnus/longus (AD). Note the fat infiltration/replacement in the PM patients.

Results

Numerical simulations

Simulation 1: Effect of an additional fat component on pulsed-qMT parameter fitting

Figure 2 shows the numerical simulations of pulsed saturation qMT with an additional fat component. For fat fractions up to 0.8, F was underestimated by progressively increasing amounts. Above the fat fraction of 0.8, F continued to be inaccurately fitted, and the fitting process was further characterized by high instability. was also underestimated and decreased monotonically as a function of fat fraction. The estimates of were always close to the known value, but the uncertainty increased with higher fat fraction, leading to high instability at high fat fractions. was overestimated and its value increased monotonically with fat fraction.

Figure 2.

Numerical simulation of pulsed saturation qMT with Ramani's model with additional fat components ranged from 0.01 to 0.96, stepped by 0.05. The parameters used to generate signals were S0 = 1, , F = 0.08, , and . RAOBS was set to 0.7 s−1. Gaussian noise was added to the generated signal to create SNR = 100. The error bars represent the SD of parameter values from 1000 iterations.

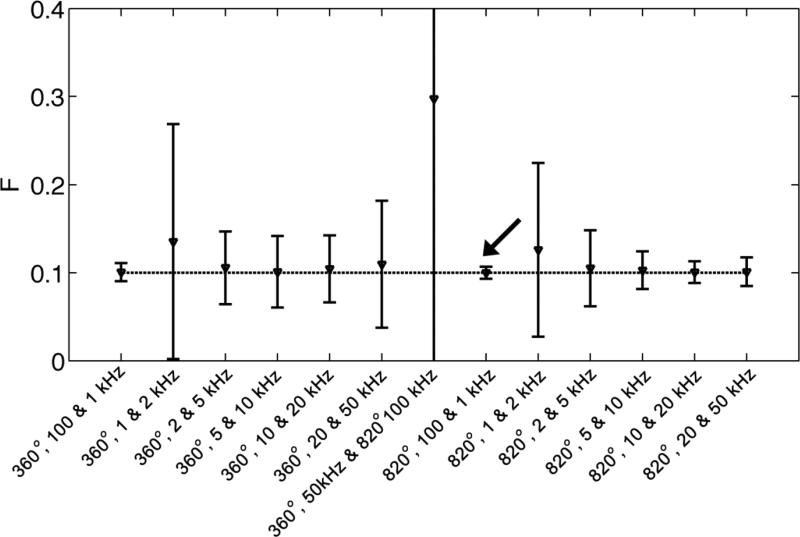

Evaluation of the consecutive pair of sampling points that produces the most accurate and precise estimation of PSR from a given scheme

Figure 3 shows the accuracy and precision of thirteen consecutive pairs of sampling points analyzed according to the two-parameter model, as predicted by the simulations. The sampling pair of [(820°, 100 kHz) (820°, 1 kHz)] yields the most accurate and precise estimation of PSR.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of the accuracy and precision of consecutive pair of sampling points from a given 14-point scheme from iterative two-parameter model fitting. It can be seen that the sampling pair of [(820°, 100 kHz), (820°, 1 kHz)] estimate F most accurately.

Simulation 3: Comparison of the 2-point scheme and the 14-point scheme at different SNR levels

Figure 4 shows the numerical simulations of the two-parameter model vs. the five-parameter model at different SNR levels. The two-parameter model produced more accurate estimates of F, especially at low SNR levels, with no effect on the uncertainty of the estimate.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the two-point/two-parameter and five-parameter approaches at different SNR levels. The two-point/two-parameter approach revealed greater robustness to low SNR than the 14-point/five-parameter approach, as revealed by greater accuracy with no loss of precision.

Simulation 4: Evaluation of potential parameter bias when using the 2-point scheme

At SNR of 100, for the variations of between 40 and 60 Hz, between 4 and 8 μs, and between 30 and 60 ms, the estimated F values had coefficients of variation of 7.5%, 14.5%, and 6.5%, respectively.

In Vivo MRI

Figure 5 shows the maps of the MRI parameters in the control and the PM patient subjects. Data from the controls are shown in Columns 1 and 2, and data from the patients are shown in Columns 3 and 4. Raw images acquired at (820°, 100 kHz) are shown in Row 1 and indicate the efficiency of using 1-3-3-1 binomial water selective excitation, especially in the patient with significant fat infiltration and replacement (Column 3). The B1+ and B0 maps are shown in the second and third rows. Generally, a low B1+ field was observed around the hamstring muscles and the lateral side of the VL muscles, with values as low as 60 - 70% of the nominal flip angle. The ΔB0 map revealed an inhomogeneity of ±30 Hz across the image. The F maps calculated with the full 14-point scheme using the five-parameter model are given in Row 4. The F maps calculated with the two-parameter model are given in Row 5, and reveal less variability and fewer edge effects at the muscle boundaries than those fitted with the five-parameter model. Parameter maps of , , , RA, and RAOBS from the five-parameter model fitting are shown in Figure 6. The values in these images are consistent with the assumptions made for the constants in the two-parameter model. For individual muscle analysis, the mean and standard deviation of the F values for both the five-parameter modeling fitting and two-parameter model fitting are presented in Figure 7. For the controls, the F values are slightly lower in the two-parameter model fitting, but with reduced variability (also shown in the F maps in Figure 5). For the patients, significantly reduced variability in F values was observed.

Figure 5.

Example raw images and parameter maps of two healthy controls (Columns 1 and 2), and two PM patients (Columns 3 and 4). Row 1: The raw images acquired at nominal flip angles of 820° and 100 kHz, indicating an efficient fat signal suppression with the 1-3-3-1 binomial water selective excitation pulse. Row 2: The B1+ maps acquired using actual flip angle method, indicating low B1+ field (~60-70% of nominal flip angle) around the SM muscle and the lateral aspect of the VL muscle. Row 3: The B0 maps acquired with a dual-echo sequence. Row 4: The F maps calculated from the full 14-point data using the five-parameter model. Row 5: The F maps calculated from the sampling points of (820, 1 kHz) and (820, 100 kHz). Note the lower F values in the second control subject and the patients around the areas of lower B1+ values in the hamstring muscles. The two-point/two-parameter approach estimated F more accurately than the 14-point/five-parameter approach, with more robustness at low SNR and reduced sensitivity to motion.

Figure 6.

The additional parameter maps from five-parameter fitting with the full 14-point data: Row 1, maps; Row 2, maps; Row 3, maps; Row 4, RA maps; Row 5, maps. These data support the use of fixed , , and values when applying the two-point/two-parameter approach.

Figure 7.

Comparison of ROI statistical analysis of F in eight individual thigh muscles in the controls (A, B) and the patients (C, D). Reduced variability is noted with the two-point/two-parameter approach.

Discussion

In this work, we have investigated a series of technical issues related to the implementation of qMT methods for skeletal muscle. Specifically, we have demonstrated that an additional fat component in skeletal muscle introduces bias in qMT parameter fitting, which would not be a confounding factor in either brain or spinal cord studies. This finding indicates the need to use fat signal-suppression or water-selective excitation methods while acquiring qMT data from skeletal muscle. Also, a two-parameter model was presented for pulsed qMT data analysis and compared to the five-parameter model, first in numerical simulations and then in experimental data. Compared to the five parameter model, the two-parameter model offers greater robustness with respect to parameter estimation (particularly at low SNR) and reduced sensitivity to motion artifacts, with minimal potential for error due to incorrect parameter estimates.

Fat signal suppression is necessary for accurate muscle qMT imaging

Fat infiltration/replacement is a common component of muscle diseases. For healthy muscles in the present study, as well as in our previous work (15), the fat fraction of thigh muscles was less than 0.10. Under these conditions, the fitted values of F are expected to be slightly underestimated when FS is not applied (Figure 2). However, complete muscle replacement by fat may occur in muscle diseases such as the inflammatory myopathies and muscular dystrophies. A clear implication of the data in Figure 2, then, is that FS is always required for qMT imaging in patients with muscle diseases. The 1-3-3-1 binomial pulse for FS used here was robust across B1+ inhomogeneities of 60%–130%, suppressing> 98% fat signals across the images (Figure 5). Other advantages of this pulse are its compatibility with 3D imaging and the absence of off-resonance pulses for fat saturation or inversion-nulling.

The two-parameter model offers advantages over the five-parameter model

Determination of the pair of sampling points that produces the most accurate and precise estimation of PSR

In simulation studies, the two-point sampling scheme with the two-parameter model produced much less bias in F values than the 14-point scheme with the five-parameter model (Figure 3). This is because, with the assumption of three more constants, the two-parameter model is more robust to noise (Figure 4). This effect is particularly strong at low SNR levels.

Among the sampling pairs tested, the [(820°, 100 kHz) (820°, 1 kHz)] sampling pair gave estimated F most accurately and precisely. However, it should be pointed out that this might not be the globally optimal scheme. To determine the global optimal sampling scheme, Cramer-Rao Lower Bound theory (18,27) or error propagation theory (10) can be utilized, based on the two-parameter model. In particular, when one sampling point is fixed as an unsaturated one, the simplified model as given in Equation [6] and error propagation theory can be simply used. These approaches were not deemed necessary because the [(820°, 100 kHz) (820°, 1 kHz)] sampling pair resulted in outstanding accuracy and precision, with irradiation power and frequency offsets close to the globally optimized values in previous studies (10,11). In the globally optimized schemes (10,11), the MT-weighted image was acquired at relatively higher irradiation power and low frequency offset, while the other image was acquired for data normalization. Although further studies could be performed to determine the globally optimum acquisition scheme for skeletal muscle qMT studies, no significant further improvement in the performance is expected. This is because the outstanding precision for the estimates of F demonstrated in this work is below the difference in F that is expected in muscle disease (Figure 7) or disease models (16).

Low potential for bias with the 2-parameter model

The simulations predict low-to-modest levels of bias in the estimated values for F (<15%), when the two-parameter model is used. Although the simulations of potential bias with the assumed constants were designed using data expected for healthy muscles, we do not anticipate significant additional bias in analyzing the patient data. This conclusion is supported by the data in Figure 6. In the regions of image with high B1+, the values are within 30 to 50 Hz in both the controls and the patients. This finding supports the use of this assumed value for . Likewise, although and RA varied significantly, is generally a constant, as shown in Figure 6, in which generally uniform and similar were obtained in both the controls and patients. Note that the variations of in the hamstring muscles likely to be due to low SNR. Finally, the fitted values are also generally similar in both the healthy controls and patients. In addition, the potential for bias in the F estimates must be balanced with the reductions in total scan duration, noise sensitivity, and data analysis time that the two-parameter approach affords.

Application to the experimental data

In the experimental data, the estimated values for F values obtained with two-parameter model tended to be lower than those obtained with the five-parameter model (Figure 7). A portion of this effect could, in principle, have come from incorrect assumptions regarding the three fixed parameters. However, the assumed values matched the experimental data and prior published results well: the assumed values for and were adopted from previous studies in healthy muscles (14,15), and the assumed value of – while ~ 50% lower than reported values from studies of the lower leg muscles (14) – is close to the determined values from five-parameter fitting (Figure 6). Another possible factor is the SNR effect, as demonstrated in the simulation results in Figure 4: at SNR levels of ≤100 and for the current experimental conditions, the F values with two-parameter fitting are usually lower and more accurate than those with the five-parameter fitting.

In addition, the parameter estimates from the two-parameter approach tended to be less variable than those from the five-parameter approach. The greatest reductions in the variability of the F estimates were identified observed in the hamstring muscles, where the B1+and SNR values are lowest. This is consistent with Simulation 3's prediction of more precise parameter estimates when using the two-parameter model to characterize low SNR data. In addition, the improvement in precision may be explained by the existence of slight motion artifacts in the subject (not shown), the errors due to which would propagate further in the case of the five-parameter fitting (because it was derived from the more motion-sensitive 14-image dataset).

Using these improvements to the qMT data analysis, preliminary observations can be made about the data from the two PM patients. In the first patient, lower F values were obtained in the RF, SM, ST and BF muscles, which may indicate inflammation. In the AD and hamstring muscles of the second patient, there were significant elevations in F for the five-parameter fitting. These appear to have been due to motion artifacts. The motion artifacts are revealed as edge effects in the F maps; but the effects of motion were minimized with the two-parameter fitting (Figure 5).

Summary and conclusions

In this work, a series of technical complications of qMT studies of skeletal muscle were evaluated, and practical solutions were identified. First, numerical simulations indicate that an additional fat component in the muscle would yield underestimated pool size ratios. Therefore, fat signal suppression or water-selective excitation is always recommended for qMT imaging. Also, to solve the confounding factors with B1+ inhomogeneities and motion artifacts, a revised two-parameter fit to Ramani's model (17) has been implemented for qMT imaging in skeletal muscle. The performance of this model was compared with the full five-parameter model by using numerical simulations in vivo data from healthy individuals and PM patients. The robustness of the two-parameter approach with respect to low SNR and incorrect assumptions was demonstrated.

This model enables rapid qMT imaging in skeletal muscles with robust parameter estimation. An advantage of the two-parameter model is that it permits a reduced data acquisition time. This reduction in imaging time can be used in either of two ways. First, presuming adequate SNR, the total exam time can be reduced (with corresponding reductions in patient burden and the likelihood of motion artifacts). Alternatively, additional excitations can be performed for signal averaging purposes. Future work may include the investigation of globally optimized two-point schemes for the two-parameter model fitting approach.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by NIH grants R01 AR057091, R01 EB014308, UL1TR000445, and K25 EB013659. The authors thank MR technologists Donna M. Butler, Kristen George-Durrett, Clair Kurtenbach, Leslie McIntosh, and David Pennell for their assistance with data acquisition and the subjects for their participation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Henkelman RM, Huang XM, Xiang QS, Stanisz GJ, Swanson SD, Bronskill MJ. Quantitative Interpretation of Magnetization-Transfer. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1993;29(6):759–766. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sled JG, Pike GB. Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer in spoiled gradient echo MRI sequences. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2000;145(1):24–36. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sled JG, Pike GB. Quantitative imaging of magnetization transfer exchange and relaxation properties in vivo using MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2001;46(5):923–931. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarnykh VL. Pulsed Z-spectroscopic imaging of cross-relaxation parameters in tissues for human MRI: theory and clinical applications. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(5):929–939. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gochberg DF, Kennan RP, Gore JC. Quantitative studies of magnetization transfer by selective excitation and T-1 recovery. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1997;38(2):224–231. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gochberg DF, Fong PM, Gore JC. A quantitative study of magnetization transfer in MAGIC gels. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2003;48(21):N277–N282. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/21/n01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gochberg DF, Gore JC. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging via selective inversion recovery with short repetition times. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;57(2):437–441. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soellinger M, Langkammer C, Seifert-Held T, Fazekas F, Ropele S. Fast bound pool fraction mapping using stimulated echoes. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2011;66(3):717–724. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Underhill HR, Rostomily RC, Mikheev AM, Yuan C, Yarnykh VL. Fast bound pool fraction imaging of the in vivo rat brain: Association with myelin content and validation in the C6 glioma model. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2052–2065. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yarnykh VL. Fast macromolecular proton fraction mapping from a single off-resonance magnetization transfer measurement. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(1):166–178. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith AK, Dortch RD, Dethrage LM, Smith SA. Rapid, high-resolution quantitative magnetization transfer MRI of the human spinal cord. NeuroImage. 2014;95(0):106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ou XW, Sun SW, Liang HF, Song SK, Gochberg DF. Quantitative Magnetization Transfer Measured Pool-Size Ratio Reflects Optic Nerve Myelin Content in Ex Vivo Mice. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009;61(2):364–371. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louie EA, Gochberg DF, Does MD, Damon BM. Transverse relaxation and magnetization transfer in skeletal muscle: effect of pH. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(3):560–569. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinclair CD, Samson RS, Thomas DL, Weiskopf N, Lutti A, Thornton JS, Golay X. Quantitative magnetization transfer in in vivo healthy human skeletal muscle at 3 T. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(6):1739–1748. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li K, Dortch RD, Welch EB, Bryant ND, Buck AK, Towse TF, Gochberg DF, Does MD, Damon BM, Park JH. Multi-parametric MRI characterization of healthy human thigh muscles at 3.0 T - relaxation, magnetization transfer, fat/water, and diffusion tensor imaging. NMR Biomed. 2014;27(9):1070–1084. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryant ND, Li K, Does MD, Barnes S, Gochberg DF, Yankeelov TE, Park JH, Damon BM. Multi-parametric MRI characterization of inflammation in murine skeletal muscle. NMR in Biomedicine. 2014;27(6):716–725. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramani A, Dalton C, Miller DH, Tofts PS, Barker GJ. Precise estimate of fundamental in-vivo MT parameters in human brain in clinically feasible times. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2002;20(10):721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cercignani M, Alexander DC. Optimal acquisition schemes for in vivo quantitative magnetization transfer MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;56(4):803–810. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li JG, Graham SJ, Henkelman RM. A flexible magnetization transfer line shape derived from tissue experimental data. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37(6):866–871. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J-H, Le HC, Koutcher JA, Singer S. Fat-free MRI based on magnetization exchange. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2010;63(3):713–718. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith SA, Golay X, Fatemi A, Mahmood A, Raymond GV, Moser HW, van Zijl PCM, Stanisz GJ. Quantitative magnetization transfer characteristics of the human cervical spinal cord in vivo: Application to Adrenomyeloneuropathy. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(1):22–27. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yarnykh VL, Yuan C. Cross-relaxation imaging reveals detailed anatomy of white matter fiber tracts in the human brain. NeuroImage. 2004;23(1):409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cercignani M, Barker GJ. A comparison between equations describing in vivo MT: The effects of noise and sequence parameters. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2008;191(2):171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yarnykh VL. Actual flip-angle imaging in the pulsed steady state: a method for rapid three-dimensional mapping of the transmitted radiofrequency field. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57(1):192–200. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skinner TE, Glover GH. An extended two-point Dixon algorithm for calculating separate water, fat, and B0 images. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37(4):628–630. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dortch RD, Moore J, Li K, Jankiewicz M, Gochberg DF, Hirtle JA, Gore JC, Smith SA. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging of human brain at 7 T. Neuroimage. 2013;64:640–649. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li K, Zu Z, Xu J, Janve VA, Gore JC, Does MD, Gochberg DF. Optimized inversion recovery sequences for quantitative T1 and magnetization transfer imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(2):491–500. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]