Abstract

Employees in EDs report increasing role overload because of critical staff shortages, budgetary cuts and increased patient numbers and acuity. Such overload could compromise staff satisfaction with their working environment. This integrative review identifies, synthesises and evaluates current research around staff perceptions of the working conditions in EDs. A systematic search of relevant databases, using MeSH descriptors ED/EDs, Emergency room/s, ER/s, or A&E coupled with (and) working environment, working condition/s, staff perception/s, as well as reference chaining was conducted. We identified 31 key studies that were evaluated using the mixed methods assessment tool (MMAT). These comprised 24 quantitative‐descriptive studies, four mixed descriptive/comparative (non‐randomised controlled trial) studies and three qualitative studies. Studies included varied widely in quality with MMAT scores ranging from 0% to 100%. A key finding was that perceptions of working environment varied across clinical staff and study location, but that high levels of autonomy and teamwork offset stress around high pressure and high volume workloads. The large range of tools used to assess staff perception of working environment limits the comparability of the studies. A dearth of intervention studies around enhancing working environments in EDs limits the capacity to recommend evidence‐based interventions to improve staff morale. © 2016 The Authors. Emergency Medicine Australasia published by John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd on behalf of Australasian College for Emergency Medicine and Australasian Society for Emergency Medicine

Keywords: ED, integrative review, staff perception, working condition, working environment

Key findings.

ED staff are conscious of many stressors that impact on their working environment.

The impact of working environment stressors is ameliorated by experience and autonomy.

The perceptions of working environment stressors by ED staff appear to differ from other clinical staff.

The multitude of tools used to assess working environment stressors make comparison difficult.

Very few studies explore interventions to improve working environment in the ED.

Background

The health care environment can be a stressful place to work.1, 2 This is an internationally recognised issue, with research being undertaken in Europe, Asia, North America, South America and Australasia.1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 EDs are often cited as particularly stressful environments, with increasing numbers and acuity of ED presentations resulting in high pressure and high volume workloads.13 These factors, combined with varied staff skill‐mix, burnout, difficulties with recruitment and retention, decreased morale and job satisfaction, personality factors, aggression and violence, interpersonal conflicts, limited recognition of quality work and disempowerment could all impact on staff and patients in terms of perception of environment, safety and risk of adverse events.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Some of these factors relate to the health workforce overall, while some pertain more specifically to the ED.

Current literature suggests that ED staff are also subject to many external pressures around patient waiting times and the deleterious impacts of shift work.13, 19, 20 Despite this, emergency is often identified as a ‘prestigious and high value’ area of clinical work, which is known to enable development of high personal levels of clinical skills and the development of positive supportive team working environments.14, 21, 22 The broad literature presents a contrasting view of EDs, as a clinical area fraught with stressors and also as an exciting and challenging environment. Synonymous with both these views, high levels of staff turn‐over, clinician burn‐out15, 18 and post‐traumatic stress disorder have been noted.18, 23, 24 These, almost dichotomous, views of EDs as both inspiring and demoralising working environments, both of which have been associated with development of burnout in ED staff,18 coupled with the increasing expectations of care delivery placed on EDs, provided impetus for a thorough and systematic evaluation of the literature regarding ED staff perception of their working environment, particularly of stressors in this space.

There has been relatively little research exploring stressors specific to the ED. Staff perceptions of their working environment and work‐related stressors are complex areas that can encompass a range of concepts, including the physical environment and the underlying personality characteristics of co‐workers.10, 14, 16, 25 Our definition of working environment encompasses factors influencing the professional context in which ED clinical staff work. The outcomes of staff stress include sick leave,26 resignation and turn‐over;16 the development of physiological alterations such as cortisol and blood pressure in staff;27 or the onset of mental health conditions such as burnout (listed in ICD10).18 However, this review focuses on subjective staff perception of their working conditions, rather than potential outcomes of their working conditions.

The aim of this integrative review is to identify, thematically group and critically evaluate published literature around ED staff members' perceptions of working environment, with a parti‐cular focus on identification of the stressors within the ED and to establish areas of deficit in existing literature to focus future research.

The questions this review aimed to answer were the following:

How do ED staff perceive their working environment?

Do gender and/or clinical roles impact staff perceptions of the ED working environment?

Are staff perceptions of the ED working environment different to those of other specialist clinical areas?

What recommendations can be drawn from the literature to guide improvements in satisfaction with ED working environment?

Methods

A multi‐stage process based on the model of Pluye and Hong28 was used for this integrative review.29, 30 Because of the varied nature of the available evidence, the mixed methods assessment tool (MMAT)28, 30 was utilised by four independent reviewers after the application of systematic inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Search strategy

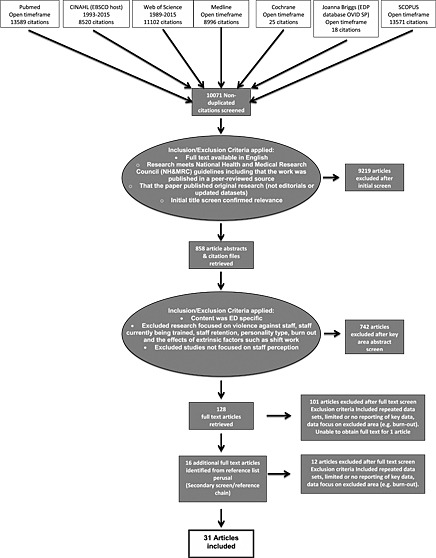

The search strategy used is represented in Figure 1. Informing the search strategy were search terms: ED/EDs, Emergency room/s, ER/s, or A&E coupled with (and) working environment, working condition/s, and staff perception/s. The included dates were 1993–Jan 2015. Activation of ‘smart text’ and automatic word variation options during searches ensured that word combination options including US and UK spelling variations and plural terms were detected. Reference chaining was undertaken. All final searches were conducted in January 2015.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the stepwise processes used in undertaking this systematic review, including inclusion/exclusion criteria applied to the papers. The numbers in each box refer to the number of papers included in each step.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they were published in English between 1993 and 2015 and focused on staff perception of working environment. Literature was excluded if it covered ED staff perception of violence against staff,17 assessment of compassion fatigue and burnout,15, 31 communication difficulties in ED,32, 33, 34 shift work,11, 19, 20, 35 internal cultural diversity36 and staff undergoing training processes (e.g. specific ED clinical training),34 as these have already been explored in highly focused reviews (see also Fig. 1).

One reviewer (AJ) screened titles and abstracts for inclusion based on criteria and retrieved 112 full‐text articles that met all criteria. Review of full text articles and a final moderation process (AJ, JC, and MW) indicated that 31 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Quality appraisal

The MMAT30 provides a structured approach for data abstraction and synthesis of themes from quantitative, qualitative and mixed method research in an unbiased manner.28 Three reviewers (AJ, LA and MW) independently evaluated the MMAT level of evidence for each article and completed an unbiased data extraction table.29

Results

Search strategies and study quality

The search resulted in 31 articles that comprised 24 quantitative‐descriptive studies, four mixed descriptive/com‐parative (non‐randomised controlled trial) studies and three qualitative studies in terms of the MMAT assessment. Studies were conducted in a range of countries (mostly Europe) and covered a range of clinical personnel (e.g. nurses, nursing assistants and doctors). The studies varied widely in quality (0–100% MMAT scores). Independent assessment of MMAT scores revealed some variability based around the research experience of the user; for this study, we reported the modal score. The studies were grouped into those exclusively exploring nursing staff (n = 12, Table 1), mixed clinical populations (n = 11, Table 2) and medical staff (n = 8, Table 3).

Table 1.

Research evidence around ED nurses perceptions of their working environment

| Author, year, country | Aim/s | Sample | Research design/tools/analysis type†, ‡ | Rigour, reliability, validity | Findings | Strengths | Limitations§ | Recommendations/implications | MMAT % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hawley, 1992, Urban Canada | To identify and describe the intraorganisational sources of stress perceived by emergency nurses | ED nurses n = 68 from four EDs |

– Descriptive cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported, previously validated, modified Stress Diagnostic Survey with 41 items each with a Likert‐type scaling 1–7 – Survey coupled with open‐ended questions – Limited participant demographic data also collected – Mixed method/§§quantitative descriptive |

– Guided by the model for organisational stress research of Ivancevich and Matteson – Stipulated inclusion criteria: RNs, >3 months ED experience |

– Emergency nurses experience work‐related stress originating from a variety of sources including inadequate staffing and resources, too many non‐nursing tasks, changing trends in ED use, patient transfer problems and also continual confrontation with patients and families who exhibited crisis or problematic behaviours |

– Study provides an interesting historical context – with limited identified impact of workload on staff stress – Informed by a strong theoretical model |

– Limited information about participant selection, follow up procedures or participation/response rate – Limited reporting of demographic data including % women |

– Required development of strategies dealing directly with stressors and the creation of a workplace that fosters more support and recognition of nurses and promotes professional growth may also help to reduce the stressors | 25 |

| 2. Helps, 1997, UK | To assess psychological and physiological experiences of occupational stressors in ED staff |

ED nurses n = 51/57 distributed across three grade levels – Single site |

– §§Mixed method study including semi‐structured interview, cross‐sectional a self‐reported quantitative questionnaire – A 42 item ‘Hassles’ Questionnaire, a General Health Questionnaire – 28, a Responses to Stress Questionnaire (RSQ) and The Maslach Burnout inventory (2nd edn) – Descriptive analysis (mean, SD, range), statistical analysis reported but tests not cited |

– 89% response rate |

– Top 10 identified ‘hassles’ were ambient temperature and Lighting, Too much to do, Budget cuts, Doctors, Erratic workload, Other nurses, People in charge, Time and work pressures, Lack of staff and interpersonal relationships were cited as the greatest sources of occupational stress – Greatest satisfaction was derived from patients (and staff) saying thank you, Providing a good service, supporting/helping/calming people – 25–30% of nurses reported significant psychological compromise – The most commonly suggested solution to stress was to employ more staff, followed by a ‘time out room’ and effective debriefing |

– Use of multiple tools enabled a broad view of these nurses states – Broad process for inclusion of staff |

– ††Validity checks not cited – Face and construct validity for ‘hassles’ and ‘responses to stress’ questionnaires not cited – No analysis of data, no identification of themes within interviews provided – No follow up of non‐respondents to the survey |

– In general, A&E nurses satisfied in their work, with overall levels of occupational stress akin to or lower than general nurses – Urgent need for debriefing for staff and high risk of PTSD – Strategies to promote successful coping and prevent the development of negative outcomes to occupational stress could then be implemented and evaluated |

25 |

| 3. Adeb‐Saeedi, 2002, Iran | To identify sources of stress for nurses working in ED |

ED nurses – 120/160 selected at random – Qualifications from school diploma (24%) to Masters trained (4%) with the majority baccala‐ureate trained (68%) |

– Mixed methods/§§quantitative descriptive including descriptive cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported validated quantitative questionnaire – Survey examining demographics and experience as well as 25 previously identified stressor items that participants were asked to rate using a 1–5 Likert scale – Analysed using spssx |

– Random sampling of possible ED nurses 75% response rate – Cronbach's alpha 0.87 |

– No significant correlation between stress, age, shift work or qualification/s – Women reported higher levels of stress – The most stressful demand on nurses was dealing with pain, suffering and grief and patient/family responses – Heavy workloads coupled with staff shortages and lack of resources also rated as highly stressful |

– Relatively good mixture of women (66%) and men (33%) staff with good distribution across working shifts |

– ‡‡, ††Sample all drawn from one University teaching pool – Not previously validated survey, no possible comparison to other study findings – Unclear how many sites involved |

– Requirement for improved support and working conditions for nurses including provision of counselling/debriefing and stress management training | 25 |

| 4. Ross‐Adjie, Leslie and Gillman, 2007, Australia | To determine which stress‐evoking incidents ED nurses perceive as the most significant, and whether demographic characteristics affect these perceptions To discuss current debriefing practices in EDs | ED nurses n = 156/300 |

– Mixed methods/§§cross‐sectional quantitative descriptive study was undertaken – Non‐parametric testing (Kruskal–Wallis) to identify and rank 15 listed workplace stressors and determine whether demographic sub‐groups ranked the identified stressors differently – Three‐part questionnaire – SPSSx was used to manage data |

– 52% response rate |

– In order of significance, stressors were the following: violence against staff, workload, skill‐mix, dealing with a mass casualty incident, the death/sexual abuse of a child, dealing with high acuity patients – There was a relationship between the paediatric death/sexual assault stressor and number of years ED experience, as well as the acuity stressor and number of years ED experience – 40% of respondents reported having personally sought debriefing while almost 60% reported that workplace debriefing is not routinely offered after a stress‐evoking incident in their workplace – Free text listing of stressors included lack of, or outdated equipment’ and ‘shift work’ |

– Quant data was enriched by free comment to contextualise findings |

– 10% respondents were men (twice the proportion employed in these EDs) – No information about survey follow up – Non‐validated, unpiloted, author developed survey may compromise survey validity and results |

– Debriefing after stress‐evoking incidents in the workplace should be mandatory not optional, and should be conducted by professionals with specific debriefing and counselling skills – Nurses perceived debriefing to be a useful part of maintaining a healthy WE – A consistent and objective system of staff allocation to manage workload and patient acuity should be implemented, matching resources with workloads |

50 |

| 5. Kilcoyne and Dowling, 2007, Ireland | To identify themes from nurses narratives around ED crowding |

ED nurses – Purposive sample n = 11 – Wide range of time in ED, 2–20 years – Single site |

– §§Qualitative study using unstructured interviews from which data were extracted using an interpretive phenomenological approach – Colaizzis 7 procedural steps for data analysis was used |

– Study participants were asked to confirm interpreted findings together with a peer validation process. Interviewer journaled their experiences to limit bias | – The primary themes that emerged around WE were lack of space, powerlessness including not feeling valued, feeling stressed, lack of respect and dignity and poor service delivery | – Enables a free flow of lived experiences to be recorded – enriching the published record around areas of stress |

– Data maybe biassed by volunteer self‐selection – Small sample from one site limits generalisability of findings – Non‐probabilistic and intentional sampling based on participant availability |

– Managers must work to listen to and act on stressors experienced by nurses in ED to improve patient care and nurses perceptions of WE | 100 |

| 6. Stathopoulou, Karanikola, Panagiotopoulou and Papathanassoglou, 2011, Greece | To document anxiety and stress levels in ED nurses |

ED nurses and assistant nurses –n = 213 – Eight adult general hospital sites |

– §§Quantitative descriptive design using cross‐sectional correlational from a self‐reported, validated quantitative questionnaire – Hamilton anxiety scale, Maslach burnout inventory and demographics + demographics – Statistical analysis using multiple regression and correlations |

– Validated scales providing quantitative parametric data – Power analysis response rate 80% |

– ~75% of ED nurses tested showed a mild (affective) degree of anxiety that was higher in women than men and weakly positively correlated with duration of WE in ED – Anxiety was marginally greater in public sector hospitals |

– Multisite – First such study in Greek EDs |

– ‡‡, ††Participants had widely varying levels of clinical education (2 year vocational training – 4 year tertiary training) – No assessment of ‘baseline’ anxiety or personal history |

– Counselling to support development and implementation of relaxation techniques, coping and problem‐solving strategies – Need for management and supervisory support |

100 |

| 7. Gholamzadeh, Sharif and Rad, 2011, Iran | To establish the sources of job stress and the adopted coping strategies of nurses working in the ED |

ED nurse volunteers – n = 90 – From three large teaching hospitals |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional study using a self‐reported questionnaire to identify the sources of job stress and nurse's profile, and Lazarus standard questionnaires to determine the types of coping strategies – Simple descriptive statistics applied (mean ± SEM) |

– Total possible population not reported – Survey well validated in previous studies – Cronbach's alpha 0.88 calculated |

– Frequent high levels of stress noted with major stressors related to physical environment and lack of equipment, work load, managing patients and family, exposure to H&S hazards, lack of admin support and lack of physician attendance – Gender difference in coping strategy: women tending to use emotion‐focussed strategies (self‐controlling and positive reappraisal) and men used a more problem‐focussed approach – Most nurses (~75%) indicated satisfaction with their job |

– Study focused on problems and potential solutions/ areas for intervention – Multisite in a geographical region where there is relatively little published literature |

– ‡‡Heavy skewed population, 87% women aged between 23 and 50 – More than half (57%) had less than 5 years ED experience – Participants volunteered, no randomisation so potential population bias – χ2 values not reported |

– Limited recommendations – Nurses tended to use a conscious effort to reduce stress centred around attempting to regulate emotional responses to stress (rather than address the stressor) |

0‐25 |

| 8. Adriaenssens, De Gucht, Van Der Doef and Maes, 2011, Belgium | To establish if job and organisational factors reported by ED nurses differ from those of general hospital nurses and to describe to what extent these characteristics can predict job satisfaction, turnover intention, work engagement, fatigue and distress |

ED nurses – n = 254/308 – Cross‐sectional study – carried out in 15 EDs of Belgian general hospitals in 2007–2008 |

– §§Comparative (non‐RCT) descriptive cross‐sectional correlational and comparative design using self‐reported validated quantitative questionnaires including the Leiden Quality of Work Questionnaire for Nurses, the Checklist Individual Strength, the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale and the Brief Symptom Inventory – each with a 4‐point Likert scale response – Descriptive statistics (chi squared) and hierarchical regression analyses for each measure, via SPSSx |

– 82% response rate – Comparison against n = 669 general nurses from a previous study Gelsema, van der Doef, Maes and Akerboom, 2005 – Senior nurses and managers excluded – 0.93 >Cronbach's alpha >0.57 on all scales |

– ED nurses reported more time pressure and physical demands, less decision authority and adequate work procedures, and fewer rewards than a general hospital nursing population – ED nurses also recorded more opportunity for skill discretion and better social support by colleagues – Work‐time was rated as an important contributor to fatigue in ED nurses – Apart from personal characteristics, decision authority, skill discretion, adequate work procedures, perceived reward and social support by supervisors proved to be strong determinants of job satisfaction, work engagement and lower turnover intention in emergency nurses |

– Multiple sites and broad study population – Comparison with general nursing population enhanced understanding of the study findings (i.e. ED nurses are demographically different to general hospital nurses – with more experience, males, qualifications, shift work and number of shifts worked per week |

– ‡‡, ††No follow‐up processes for non‐respondents |

– Further investigation of job and workplace characteristics is required to curtail ED nurses stress‐health problems – Increasing skills, autonomy, effective working procedures and quality supervisors will positively impact on ED nurses |

75 |

| 9. Wu, Sun and Wang, 2012, China | To describe factors linked to occupational stress in ED nurses |

ED nurses – n = 510 – 16 hospital EDs – In Liaoning province |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported validated quantitative questionnaire – Chinese version of the Personal strain questionnaire + demographics + information about occupational roles (overload, insufficiency, ambiguity, boundaries, responsibilities) + personal resources (recreation, self‐care, social support and rational coping) – One‐way ANOVA Pearson correlation, general linear regression modelling |

– Validated scales providing quantitative ordinal (parametric see ‡) data on scale of 1–5 – Data tested for normality – Response rate 78% |

– Female ED nurses report greater work stress than reported in other occupational groups – Personal strain or ‘stress’ was correlated with role overload, role boundaries, role insufficiencies, lack of social support, chronic disease and inadequate self‐care |

– Included EDs with varying patient loads – Comparison with equivalent data from a broader population |

– ‡‡, ††Only 0.4% of potential population was men – EDs were all located in urban regions – No follow up of non‐respondents to the survey |

– Improve work conditions, health education and occupational training to reduce stress in female ED nurses | 100 |

| 10. Chiang and Chang, 2012, Taiwan | To compare the levels of stress, depression, and intention to leave amongst clinical nurses employed in different medical units in relation to their demographic characteristics |

ED nurses – 29/314 – Recruited from regional hospitals in the Northern area Taiwan – Nurses >99% women |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported quantitative questionnaire, including the context‐specific adaptation of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D), the Perceived Stress Scale, Intention to Leave Scale and general demographic information including hospital area of work – Descriptive statistics, and Spearman's correlations for all study variables to identify possible factors for multiple regression modelling, ANOVA to identify clinical area differences |

– Used validated scales |

– Significant variations in reported stress levels in nurses, with ER nurses rating fairly low in the categories of nurses who were stressed, depressed and intending to leave – Demographic characteristics (i.e. tenure, marital status, education, and age) were not mainly influential factors in the level of stress, depression, and intention to leave amongst nurses in various medical unit and thus other factors need to be considered |

– Good comparison of ER nurses compared with other speciality nurses and general nurses within the same hospital environments – Inexperienced nurses and nurses who were married were more likely to intend to leave and more likely to show signs of depression – Samples drawn from multiple sites |

– ‡‡, ††Almost no male nurses – Relatively few (~9%) ER nurses – Limited information provided about recruitment strategies and response rates – Number of discrete data collection sites is unclear – Sample sizes from different clinical units varied; therefore, results need to be considered with caution and may lack generalisability – Limited follow up of non‐respondents to the survey |

– ER is a relatively well supported WE for north Taiwanese district nurses compared with other clinical areas – Requirement broadly for policymakers and nursing managers to more clearly direct policies that correctly reflect effective nursing human resource management |

50 |

| 11. Adriaenssens, De Gucht and Maes, 2013, Belgium | To repeat a previous study: to establish if job and organisational factors reported by ED nurses differ across time (18 months) and to describe to what extent these characteristics continue to predict job satisfaction, turnover intention, work engagement, fatigue and distress in ED nurses. |

ED nurses – n = 170/204 nurses still working from previous study, 2007–2008; where n = 254 was carried out in 15 EDs of Belgian general hospitals in 2009 |

– §§Comparative (non‐RCT) descriptive cross‐sectional correlational and comparative design using self‐reported validated quantitative questionnaires including the Leiden Quality of Work Questionnaire for Nurses, the Checklist Individual Strength, the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale and the Brief Symptom Inventory – each with a 4‐point Likert scale response – Descriptive statistics (chi squared) and hierarchical regression analyses using difference scores (T1 versus T2) for each measure, via SPSSx |

– 83% response rate – Comparison against n = 254 ED nurses from a previous study Adriaenssens et al., 2011 – Senior nurses and managers excluded – 0.95 > Cronbach's alpha >0.56 on all scales |

– One‐fifth of nurses (~20%) had left ED nursing positions over the 18‐month study period with large variance between sites (5–36%) – Gender differences included that female nurses reported higher job satisfaction, higher work engagement and lower emotional exhaustion – Reported job demands remained high but stable over time, while social support and intention to leave varied widely, as did control, predicted job satisfaction, work engagement and emotional exhaustion, reward, social harassment and work agreements. This suggests a rapid and significant flux in nurse perception of working conditions can occur |

– High repeated response rate – Large sample size for comparison | – ‡‡No consideration of ED or hospital size or setting – High turnover may bias results, recording exclusively from ‘survivors’ – staff who remained | – Staff turnover rates can be very high and cause a significant loss of staff capital – Rapid (~18 months) changes in nurse reported work‐related factors influencing stress provides managers many opportunities to positively impact on WE and staff satisfaction – Frequent assessment of WE in ED is important, as it can change rapidly and impact staff retention | 75 |

| 12. Kogien and Cedaro, 2014, Brazil | To determine factors that may increase nurse‐related work stress and decrease quality of life for ED nurses |

ED nurses – n = 189 – Wide range of ages, experience and average workloads |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional study using a correlational design from a1 self‐reported validated quantitative surveys including the Job stress scale, the WHOQOL‐brief and the job content questionnaire – Analysed using SPSSx and MS Excel – Pearson's χ2 test (or Fisher's exact test, when necessary) for the categorical variables, and Student's t test was used for the continuous variables, then, multivariate analysis using logistic regression was performed and the odds ratios (OR) were obtained and adjusted for socio‐demographic variables |

– An estimated 50% proportion of staff totals drawn from a large ED (Rondonia) – Helps to support an international conceptualisation of the work stressors in EDs |

– Low intellectual engagement, poor social support and high occupational demands or a passive work expectation were the main risk factors for concern in the physical domain of quality of life, altering rest/sleep quality – Psychological demands of ED environment are high – with staff exposed to pain, distress, helplessness, anxiety, fear, hopelessness, feelings of abandonment and loss – Working conditions can be poor because of overcrowding, scarcity of resources, work overload and the fast pace of the work required of the professionals providing care |

– Little research undertaken in South America and published in English – Strong and comprehensive statistical analysis of quantitative and qualitative data |

– ‡‡Non‐probabilistic and intentional – Biased population (76% women; 81% nursing technicians) – Sampling based on participant availability – No follow up of non‐participation – No information provided about response rate |

– Increase social support for staff in EDs to reduce the negative consequences of stress on staff, promote wellness, provide a predisposition to good health and improve indicators of quality of life | 50 |

Note: all survey completion was deidentified and voluntary, with appropriate accompanying ethical approval unless noted otherwise.

Data type (quantitative/qualitative) is identified in the study and/or on the basis of the analysis performed.

Note: all survey and interview data are subject to potential prevarication bias and even response falsification. Additionally, the selections required in surveys are often ‘relative’ and so can be challenging ascertain consistently and reliably (‘soft’ responses). Additionally, there may be a response bias based on the psychological well‐being of participants (single point in time survey).

There were additional study findings not related to the focus of this review not reported here.

Convenience (cross‐sectional) sampling and thus no causal inferences can be drawn.

No provision for open‐ended responses so participants' responses are constrained by study.

MMAT classification system.

EM, Emergency Medicine; ER, Emergency room; MMAT, mixed methods appraisal tool; NWI‐R, revised nurse work index; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; RA, research assistant; RN, registered nurse; RPPE, Revised Professional Practice Environment; SAS, statistical analysis systems; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the mean; SPSSx, statistics package for the social sciences; USA, United States; WE, work environment; WHOQOL, World Health Organization Quality of Life.

Table 2.

Research evidence around mixed ED clinical staff perceptions of their working environment

| Author, year, country | Aim/s | Sample | Research design/tools/ analysis type† | Rigour, reliability, validity‡ | Findings | Strengths | Limitations§ | Recommendations/ implications | MMAT % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Joe, Kennedy and Bensberg, 2002, Australia | To demonstrate a comprehensive workplace health survey that is able to identify indicators that contribute to staff workplace welfare | n = 323/500 staff from seven Melbourne suburban public hospital EDs with similar attendance numbers, case mix and demography n = 59 doctors, n = 198 nurses, n = 30 clerical/admin staff and n = 22 other staff |

– §§Quantitative descriptive study using a cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported validated employee survey designed by Service Management Australia (a subsidiary of Marketshare) with terminology within the survey altered to make it relevant to the ED – Included closed, rating (5‐point scale) and open questions for quant and qual content; mixed methods study – Calculated a ‘performance gap’ around key issues – the difference between importance rating and perceived performance rating |

– 64% response rate – Employee survey commonly used (Marketshare); refined and validated regularly by research conducted locally and compared with data from abroad |

– Staff rated a safe environment, professional standards, and staff morale the most important factors for workplace health. They were most satisfied with the flexibility of work arrangements (86%) and leadership (80%), and were least satisfied with the performance management of staff (69%) and job satisfaction and morale (67%) – The largest gaps between perceived importance and performance were in the provision of safe well‐lit parking, staff morale, and the use of reward and recognition systems |

– Utilised widely used mixed method survey tools across a number of sites and a wide range of staff – Explored a range of ED aspects from communication and staff morale to staff injuries |

– ††Skewed population; 75% women and 61% nurses – No follow up of non‐respondents to the survey |

– Provides direction for further research into ED workplace health, enabling refinement of indicators reflecting various aspects of workplace health, and correlation of indicators with sick leave, stress and injury – Also indicators of how various indicators affect different staff groups and Workplace health in EDs | 100 |

| 2. McFarlane, Duff and Bailey, 2004, Jamaica, West Indies | To explore factors associated with occupational stress in ED staff and the coping strategies used |

28/33 of health personnel working in the A&E n = 15 doctors, n = 8 registered nurses and n = 5 enrolled assistant nurses – Single site |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional design using two self‐reported, trialled, quantitative and open‐ended (qualitative) items that included limited demographic information – Open‐ended data were analysed thematically |

– Response rate = 85%, 54% doctors, 29% registered nurses and 18% enrolled assistant nurses | – A&E was reported to be stressful, with the major sources of stress reported as the external environment and the amount and quality of the workload and resulted in emotional, physical and behavioural symptoms – Effective use of humour, teamwork and ‘extracurricular’ activities in buffered the effects of stress | – Little published information from West Indian hospitals |

– Abstract only available – No evidence of ethical approval |

– Increased monetary compensation, more staff and positive feedback from managers as factors that may relieve work stress – Organised counselling and stress management programmes may be useful |

25 |

| 3. Escriba‐Aguir and Perez‐Hoyos, 2007, Spain | To determine if psychosocial WE differentially altered psychological well‐being for ED clinical staff | SSEM members including ED doctors and nurses Reported n = 639; data collected from n = 278 nurses and n = 358 doctors |

– §§Quantitative descriptive study using a cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported validated quantitative questionnaire – Mental health and vitality dimension of the SF‐36 Health survey, emotional exhaustion dimension of Maslach's burn‐out inventor and the job content questionnaire – Descriptive statistics and logistic regression |

– Supported by Karasek and Theorell's demand‐control WE model – Careful consideration of potential confounding factors including socio‐professional and gender‐role related variable – Response rate 68% |

– Psychosocial WE factors strongly influenced clinical staff psychological well‐being, but the effect varied in nurses and doctors – Doctors were more likely to show low vitality, poor mental health and high levels of emotional exhaustion from high psychological demands – Low levels of job control and co‐workers social support also increased the risk of poor mental health in doctors and the risk of high emotional exhaustion in nurses – Little impact of physical workload on reported well‐being – Lack of supervisor support for doctors but not nurses |

– Baseline data comparison with normative data from American health professionals – Comparison across health professionals drawn from a similar clinical pool |

– ‡‡, ††Sample all drawn from one professional society – No information provided about the number of EDs or the size/busyness of the ED on results – Limited follow up of non‐respondents to the survey |

– Greater need for capacity of control for doctors in EDs – Need for further investigation including the role of professional career choices and work‐family roles on clinical staff in ED – Need to establish improvements in psychosocial WE to reduce the risk of psychological distress in ED clinical staff, especially doctors |

75 |

| 4. Magid, Sullivan, Cleary et al., 2009, USA | To assess the degree to which ED staff felt that EDs are designed, managed, and supported in ways that ensure patient safety, including the physical work environment, staffing, equipment, supplies, teamwork and coordination with other services |

n = 3562 from 69 sites – Participation invited from sites affiliated with the Emergency Medicine Network, postings on emergency medicine list‐servers and through presentations at emergency medicine meetings |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional design using a self‐reported, extensively validated 50 question quantitative questionnaire that included limited (5) demographic questions – Multisite research included collecting information about size, complexity of each research site – Response rate 66% random sample of 80 eligible staff at each ED who worked an average of one or more ED clinical shifts per week – Eligible survey respondents included physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and nursing assistants – Respondents had the option of completing a paper‐based instrument or completing the survey online – Analyses were weighted to adjust for the differential sampling rates, differential nonresponse rates, and respondent job class |

– The developed scales generally had good reliability (Cronbach's): physical environment (0.60), staffing (0.65), equipment and supplies (0.93), nursing (0.90), teamwork (0.60), culture (0.79), triage and monitoring (0.91), information coordination and consultation (0.64), and inpatient coordination (0.88) – 69/102 sites initially interested actually took part (68%) – Nonrespondents received two additional surveys at 2‐week intervals, for a total of three surveys during 6 weeks – Adjustment to acceptable alpha level (0.003) due to multi‐testing |

– Survey respondents commonly reported problems in four systems critical to ED safety: physical environment, staffing, inpatient coordination and information coordination – Generally, factors around working environment, including ‘blame’ culture, staff supervision, cross‐discipline team work, were rated very highly. |

– Multiple step survey development, validation, piloting and testing establishing face and construct validity – Piloted at 10 EDs and then administered to 65 different EDs across the USA |

– ‡‡Excluded military, Veterans Administration, and children's hospitals, as well as hospitals in US territories – A modest honorarium was given to survey respondents to minimise nonresponse bias – Four EDs with response rates of 45% or less and individual questionnaires with answers to less than 80% of the survey items were excluded – Results of this study may not be generalisable to all EDs, because the facilities that participated in this study tended to be larger, were more urban and were more likely to be affiliated with an emergency medicine training programme than the typical US ED – Self‐selection bias; namely, the institutions that participated in the study were more interested in and more aware of concerns surrounding patients safety than the average US ED |

– Substantial improvements in institutional design, management, and support for emergency care are necessary to maximise patient safety in US EDs | 100 |

| 5. Healy and Tyrrell, 2011, Ireland | To examine nurses' and doctors' attitudes to, and experiences of, workplace stress in three EDs |

n = 103/150 – Convenience sample of n = 90 nurses and n = 13 doctors from three EDs |

– Descriptive cross‐sectional design from a self‐reported 16 item survey with a mixture of yes/no, Likert‐type (quantitative) item response and open‐ended questions and some additional experience and demographic data – Descriptive statistics (count, mean ± SEM) and χ2/Mann–Whitney U comparative tests |

– 69% response rate – Non‐validated, unpiloted, author developed survey may compromise survey validity |

– Most commonly identified stressors were ‘work environment’ including rostering, workload, crowding, traumatic events, shift work, doctor turnover, inter‐staff conflict, poor teamwork and poor managerial skills – Generally, older and more experienced staff reported less stress – Little managerial/workplace support to manage stress – Violence in the workplace and death/resuscitation of critically ill patients were frequently cited as stressful |

– Open questions enabled ED staff to construct their own descriptions of stressors and stress priorities, creating a rich dataset |

– No information about survey follow up, preservation of anonymity, hospital size provided– 10% nurses and 61% doctors were men – No multifactorial analysis |

– ED staff need protect from relentless stress, particularly younger less experienced staff who are most vulnerable to the effects of stress – Managers must establish a supportive culture that recognises the real issues around staff stress and demonstrate they value staff |

50 |

| 6. Flowerdew, Brown, Russ, Vincent and Woloshynowych, 2012, London, UK | To identify key stressors for ED staff, explore positive and negative behaviours associated with working under pressure and consider interventions that may improve ED team functions |

Purposive sampling recruitment of medical and nursing staff of varying seniority – Recruitment continued until no significant new themes emerged during interview (‘theoretical saturation’) – n = 22 staff, n = consultants, n = 7 registrars, n = 5 lower grade doctors, n = 6 nurses – Single site |

– §§Qualitative – Semi‐structured interviews were recorded and anonymously transcribed and analysed to extract broad themes from the interviews, and responses were coded using the NVivo computer programme |

– Themes were independently confirmed by a second researcher – Coded material was subject to member check to reduce investigator bias |

– Identified stressors included the ‘4 h’ targets, excess workload, staff shortages and lack of teamwork, both within the ED and with inpatient staff – Leadership and teamwork are mediating factors between objective stress (e.g. workload and staffing) and the subjective experience – Impacts of high pressure on communication practices, departmental overview and the management of staff and patients, as well as high levels of misunderstanding between senior and junior staff – Effective leadership and teamwork training, staff breaks, helping staff to remain calm under pressure and addressing team motivation all part of the solution |

– Information drawn from a variety of clinical staff using an open‐ended set of questions to allow themes to emerge – Study explored problems and possible solutions – Use of direct quotes adds participants' ‘voices’ |

– ††Interviews reflect self‐reported behaviour and may be biassed by ineffective recollection, misunderstanding or embarrassment |

– Identified that many ED staff lack training in coping strategies and in ‘non‐technical skills’ such as communication, situational awareness and leadership that could be rectified – Building a resilient team with strong leadership is integral to being able to withstand the pressures of the ED |

100 |

| 7. Yates, Benson, Harris and Baron, 2012, UK |

To compare levels of psychological health in medical, nursing and administrative staff from a UK ED with a comparative orthopaedic department – Also, to investigate the influence of coping strategies and the support people receive from their colleagues (i.e. social support) |

n = 136 – Emergency (n = 73) and orthopaedic (n = 63) staff – Single site (two departments) |

– §§Quantitative cross‐sectional design using four self‐reported quantitative surveys including the General Health Questionnaire‐12 (GHQ12), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Brief COPE consisting of 14 scales, each of two items and a brief (three‐item) measure of social support – Descriptive statistics (percentage and correlation) |

– Insufficient information provided to comment – 73 (50%) ED staff (30 nurses, 19 doctors, 24 administrative staff) and 63 (39%) OD staff (32 nurses, 16 doctors, 15 administrative staff) |

– Proportion of staff experiencing clinically significant levels of distress was higher than would be expected in the general population – Better psychological health was associated with greater use of problem‐focused coping and less use of maladaptive coping – Social support was associated with better psychological health and greater use of problem‐focussed coping – Emergency physicians, but not other ED staff, reported an increased risk of psychological distress – Increased psychological health was associated with the use of problem‐focused coping strategies and higher levels of social support at work – Those reporting lower levels of psychological health were more likely to use maladaptive coping strategies |

– One of the few studies incorporating a direct control/comparison group |

– ††, ‡‡Little information supplied regarding recruitment and participation – No ethical approval noted – Overall sample was heterogeneous (ED/OD) and the sub‐samples were relatively small and did not allow an analysis of potential differences between staff groups within each department – Reliance on self‐reported survey data may have compromised the richness of data |

– Priority should be given to developing and evaluating interventions to improve psychological health in ED staff – Coping strategies and social support are important factors to incorporate into such interventions to improve psychological health in ED staff – Use of problem‐focused coping strategies and social support may be important factors to incorporate into intervention – Need for further research |

25 |

| 8. Ajeigbe, McNeese‐Smith, Leach and Phillips, 2013, USA | To examine the impact of a teamwork training protocol on perception of job environment, autonomy and control over practice in ED clinical staff |

n (intervention) = 166 RNs and 25 MDs – n (control) = 267 RNs and 40 MDs – Convenience sample of RNs and MDs from all shifts, from eight sites; four sites received teamwork training and four did not |

– Comparative non‐RCT descriptive study with a cross‐sectional correlational design using self‐reported validated quantitative questionnaires including the healthcare team vitality instrument a 10‐item, 5‐point Likert‐type scale survey, and revised nurse work index (NWI‐R), both previously validated in many health care settings – Descriptive analysis and t‐tests conducted using SAS |

– Inclusion criteria for staff at both sites included that they had worked in ED for at least 6 months and were either full or part‐time – Staff demographics and ED experience align closely – 0.91 Cronbach's alpha > 0.84 |

– ED clinical staff who received teamwork training showed higher levels of staff perception of job environment, autonomy and control over practice. This included more positive perceptions by staff of access to resources and feeling like their opinions were more valued | – Interventional study exploring effects of a positive intervention on ED staff perception of WE |

– ‡‡, ††No segregation of effects on MD versus RN – No data around response rate presented |

– Training interventions can rapidly and positively affect staff perception of working environment, and this may also impact on patient care and safety, as well as staff turnover | 50 |

| 9. Person, Spiva and Hart, 2013, USA | To examine the culture of an ED examining influences including stressful situations, pressure to perform and work‐life balance |

– Included ED nurses, physicians, clinical care partners, technicians, customer servicers, leadership and support staff – n = 250 – n = 120 observation periods of 430 h – Interviews, n = 34 |

– §§Qualitative study using focused ethnographic exploration – Included a 16‐item demographic survey and informal and formal interviews, field notes, journaled identification of potential biases – Constant comparative method with external verification and calculation of cultural salience – Free listing responses |

– Team member checks and meetings, reflexive journaling and audit trail including field notes, audiotapes, transcripts | – Culture primarily described by four categories; cognitive including teamwork and ability to multi‐task; environmental including limited physical space, poor work flow and overcrowding mixtures of acute and chronic stressors, technological limitations; linguistic including issues around barriers to communication and miscommunication and social attributes, siloing of knowledge and access, unprofessional behaviours, leadership (and staff) turnover, rites of passage |

– Exploring a rich and wide range of staff perceptions – by direct observation and self‐reporting – Examining stressors within a working context – Data captured across a range of shift days and times – Enabling subtle influences on work place stress to be revealed |

– Only a small portion of the ED culture revealed – Not easily replicated – No adjustment for experience or other demographic factors – Varied recording times – One ED site |

– Management must value staff – Improve workflow processes and remove barriers – Development and training opportunities required for staff |

100 |

| 10. Rasmussen, Pedersen, Pape et al., 2014, Denmark | To determine the relationships between staff perception of WE and the occurrence of adverse events |

n = 124 – n = 98 ED nurses, n = 11 medical specialists and n = 15 junior doctors – One study site |

– Quantitative descriptive using a cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported validated quantitative questionnaire – Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire job demands and influence components + demographics – Linear regression analyses + descriptive stats |

– Validated scales providing quant parametric data – Response rate 91% |

– Four of the five working scales included in the staff perception of working environment questionnaire returned ‘poor’ findings and were positively correlated with incidence of adverse events; poor team climate, poor inter‐departmental working relationships, poor safety climate, greater cognitive demands | – Data collected across clinical disciplines, demonstrates the clinical importance of staff perception of working environment for patient safety | – ‡‡, ††No description of survey follow up to encourage participation | – Ongoing assessment of adverse events in ED must be assessed in light of staff perception of the working environment | 75 |

| 11. Lambrou, Papastavrou, Merkouris and Middleton, 2014, Cyprus | To examine nurses' and physicians' perceptions of professional environment and its association with patient safety in public EDs in Cyprus |

n = 224 – n = 174 nurses and n = 50 physicians – All five possible public ED sites |

– Quantitative descriptive study cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported validated quantitative questionnaire including the Revised Professional Practice Environment (RPPE) Scale and (b) the Safety Climate Domain of the Emergency Medical Services Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (EMS‐SAQ) each with 4‐ to 5‐point Likert scale ratings – Demographic and professional experience data were also collected – Descriptive statistics, Mean differences were assessed using t‐tests and ANOVA, Bivariate association was evaluated using Pearson's correlation coefficients – Logistic and stepwise multiple regression modelling were undertaken to determine important relationship factor predictors |

– 224/277 of possible participants (81% response rate) – 174/210 eligible nurses – response rate 83%, and 50/67 physicians – response rate 75% – The internal consistency of each of the RPPE sub‐scales was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient |

– Medical staff rated the professional practice environment slight more highly than nursing staff, particularly around ‘staff relationships’, ‘internal motivation’ and ‘cultural sensitivity’. While both groups rated teamwork highly, both groups also rated ‘control over practice’ as the lowest domain examined ‐Staff are highly motivated and in indicate that they value and practice team work |

– Clear data collection period and well‐stipulated eligibility criteria – Reasonable gender spread; women (54%) of sample amongst both physicians and nurses (56% and 53%, respectively) – Direct comparison with staff from other hospital areas was possible – Previously undertaken research also enabled longitudinal comparison of data from nurses across three previous years |

– ‡‡No description provided of other possible sites (private?) – RPPE Questionnaire was used in both medical and nursing staff, and some questions could have been perceived differently by the participants; impacting responses provided – A relatively low Cronbach's alpha was observed for two factors of the PPE as well as for EMS‐SAQ (safety domain) |

– Improvements in professional environment can ultimately improve patient safety – Identified a need to focus on leadership interventions on the problematic areas to create an environment that is conducive to the delivery of safe and high‐quality care |

100 |

Note: all survey completion was deidentified and voluntary, with appropriate accompanying ethical approval unless noted otherwise.

Data type (quantitative/qualitative) is identified in the study and/or on the basis of the analysis performed.

Note: all survey and interview data are subject to potential prevarication bias and even response falsification. Additionally, the selections required in surveys are often ‘relative’ and so can be challenging ascertain consistently and reliably (‘soft’ responses). Additionally, there may be a response bias based on the psychological well‐being of participants (single point in time survey).

There were additional study findings not related to the focus of this review not reported here.

Convenience (cross‐sectional) sampling and thus no causal inferences can be drawn.

No provision for open‐ended responses so participants' responses are constrained by study.

MMAT classification system

A&E, accident and emergency; hrs, hours; MD, medical doctor; MMAT, mixed methods appraisal tool; OD, Orthopaedics department; RN, registered nurse; RPPE, Revised Professional Practice Environment; SAS, statistical analysis systems; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the mean; SPSSx, statistics package for the social sciences; SSEM, Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine; SHOs, senior house officers; USA, United States; WE, work environment; WHOQOL, World Health Organization Quality of Life.

Table 3.

Research evidence around ED doctors' perceptions of their working environment

| Author, year, country | Aim/s | Sample | Research design/tools/ analysis type† | Rigour, reliability, validity‡ | Findings | Strengths | Limitations§ | Recommendations/implications | MMAT % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Heyworth, Whitley, Allison and Revicki, 1993, UK | To describe occupational stress, depression, task and role clarity, work group functioning and overall satisfaction in senior ED medical staff |

n = 201 respondents – n = 154 consultants (71%) and n = 47 senior registrars (77%) drawn from a register of all ED consultants and registrars |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported validated questionnaire, including the work‐related stress, depressive symptomatology and respondent evaluations of three aspects of the WE: task and role clarity, work group functioning, and overall satisfaction with work – General demographic information including hospital/ED size and average capacity, years of service and shift patterns – Descriptive statistics, and Pearson's correlations to relate factors – ANOVA to compare respondent subgroups |

– 72% overall response rate, response rate from consultants 71% and 77% from senior registrars – Survey tools previously validated in other groups of medical staff – No ethics approval listed |

– Overall levels of occupational stress and depression were low WEs were evaluated favourably – Levels of occupational stress were proportional to ED size, but not on‐call work, patient or staffing and was similar to those reported by other groups of health care providers – Respondents generally considered tasks and roles to be clearly defined, work groups to be supportive, efficient units and work satisfying – Senior staff with >10 years ED experience and consultants over 45 years old reported more satisfaction with work and work group functioning, and perceived their tasks and roles to be significantly clearer |

– Captured a large proportion of this clinical group and thus multi‐site information – Quantitative analysis of a number of key variables cited in literature |

– ††, ‡‡Highly skewed population – with a high proportion of married (86%), men (88%) respondents – Limited analysis (no factor analysis/regression attempted) – Limited follow up of non‐respondents to the survey |

– Staff stress‐management probably reflects the personality of physicians – Continue to identify character traits of successful ED practitioners to provide a proven personality profile for junior doctors considering a career in ED – Provide and encourage use of counselling |

75 |

| 2. Williams, Dale, Glucksman and Wellesley, 1997, UK | To investigate the relationship between accident and emergency senior house officers' psychological distress and confidence in performing clinical tasks and to describe work‐related stressors | n = 171 newly appointed ED SHOs from 27 hospitals |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional design using two self‐reported and open‐ended qualitative questionnaires that included, demographic questions, modified mental health – Inventory, four from the 28 item general health questionnaire, 2× case report descriptors of recent ‘stressful’ scenarios and a list of recent personal stressors |

– No ethics approval listed – Questionnaire piloted in a similar group of users prior to distribution response rates to the questionnaires were 82% (140/171) at the start, 77% (132/171) at the end of the first month, 64% (110/171) at the end of the fourth month, and 67% (115/171) at the end of the sixth month – Questionnaire component response reported varied – n = 97 to 116 (57–68%) |

– Participants with lower confidence at the end of the first and fourth months showed significantly higher distress scores than those with higher confidence levels – Work stressors centred around three areas; the type of problem presented by the patient, communication difficulties and department organisational issues – Key stressors identified included intensity of workload, coping with diagnostic uncertainty, working alone, working unsocial hours and experiencing fatigue |

– Repeated surveying explored changes in work stressors across time – Use of 100 mm visual analogue scales for participants to score responses (0 = not at all confident, 100 = very confident) |

– ††Researchers cite that the distress questionnaire and confidence rating scale had not been tested for reliability and validity, and there was no control for the potential problem of reactivity in terms of biassed response sets – Relatively small population to sample |

– Training in communication skills may be beneficial and provide the opportunity for case review – Need for further focused research on each identified domain of concern (communication, patient problem and department organisation) |

75 |

| 3. McPherson, Hale, Richardson and Obholzer, 2003, UK | To identify levels of psychological distress in accident and emergency (ED) senior house officers so as to plan interventions that will help ED staff cope better in an intrinsically challenging environment | n = 37/64 SHOs from six EDs at district general hospitals in north London |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional design using two self‐reported, extensively validated questionnaires that included, demographic questions – General Health Questionnaire (GHQ; 28 items each with four response options, subdivided into anxiety, depression, health and social functioning and Brief COPE has 28 items with four response options covering nine scales: substance misuse, religion, humour, behavioural disengagement, use of support, active coping/planning, venting/self‐distraction, denial/self‐blame and acceptance – Correlational analyses using Pearson's r |

– 58% response rate |

– 51% respondents scored over the threshold for psychological distress, higher than for other groups of doctors and for other professional groups – The coping style ‘Venting’ was significantly related to greater anxiety (r = 0.34; P < 0.05) and depression (r = 0.33; P < 0.05), while the coping style ‘Active’ was significantly related to lower anxiety (r = −0.38; P < 0.05), somatic complaints (r = −0.46; P < 0.001) and years since qualification (r = 0.40; P < 0.05) |

– 100% completion rate for this select group of staff drawn from six district general hospitals | – ††, ‡‡Non‐probabilistic and intentional sampling based on participant availability |

– An intervention to improve coping strategies may be useful for this group of doctors – Attention to aspects of psychological working conditions in ED may be essential to meet staff recruitment and retention targets – Requirement for managers and consultants to generate a culture that supports training and development of evidence‐based coping skills |

50 |

| 4. Burbeck, Coomber, Robinson and Todd, 2002, UK | To assess occupational stress levels in ED consultants |

UK practicing ED consultants complete lists provided by British Association of Emergency Medicine (BAEM) and the Faculty of Accident and Emergency Medicine (FAEM) – n = 371/479 responses – 350/479 survey completion |

– Mixed methods including §§quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported validated questionnaire – Demographic and work‐related information and included the general health questionnaire‐12 (GHQ‐12) to assess psychological distress, 15 and the symptom checklist‐depression scale (SCL‐D) to measure depression – Non‐parametric statistics for GHQ‐12 and SCL‐D scores. Qualitative data, including aspects of the job respondents enjoyed, analysed using the constant comparative method to develop coding frames – Logistic regression was used to build a predictive model of GHQ‐12‐ and SCL‐D – Demographic and stressor variables were correlated individually with both GHQ‐12 and SCL‐D scores. The six most highly correlated stressors were entered as independent variables in multivariate logistic regressions with GHQ‐12 and SCL‐D scores as dependent variables |

– Validated scales providing scaled data (non‐parametric‡) – Response rate = 78% – Completion rate 73% |

– High levels of psychological distress amongst doctors working in ED compared with other groups of doctors – Respondents were highly satisfied with ED as a specialty – The number of hours reportedly worked during previous week significantly correlated with stress outcome measures – Factors including ‘being overstretched’, ‘effect of hours’, ‘stress on family life’, ‘lack of recognition’, ‘low prestige of specialty’ and ‘dealing with management’ were all shown to be important |

– Large pool of specialist clinicians – Commonly used tools and thus comparison with other doctors was possible – Free text options enabled key themes to be identified – Open‐ended text questions and stressful scenario description for qualitative comment – Also explored the effects of ‘protective’ factors identified in other studies (minimal input) |

– ††, ‡‡Sample all drawn from one professional society – Limited follow up of non‐respondents to the survey |

– Assessment of characteristics, or combination of characteristics, within ED that are particularly problematic – Requirement for NHS provision of employment environments, in which doctors can practice effectively without compromising health |

100 |

| 5. Taylor, Pallant, Crook and Cameron, 2004, Australasia | To evaluate psychological health of ED physicians and identify factors that impact on their health |

– n = 323 – ACEM fellows |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported validated questionnaire – Perceived stress scale, Zung depression scale, Zung anxiety scale, Revised life orientation test, Mastery scale, Physical symptoms checklist, Perceived control of internal states scale, Satisfaction with life scale + demographics – Pearson's correlations, ANOVA and t‐tests |

– Validated scales providing quantitative ordinal (parametric‡) data on scale of 1–4 to 1–10 – Response rate 64% |

– Significant positive correlation between work and life satisfaction and perception of control over hours worked and professional activity mix – Significant negative correlation between work and life satisfaction and work stress – Maladaptive strategies (alcohol/drugs/disengagement) positively associated with anxiety, depression and stress – Very weak relationship between work stress/satisfaction and demographic, workplace factors or hours worked aside from gender |

– Comparison to community population data – Conservative statistical significance set at 0.01 – Good follow up of non‐responders to limit possible bias by responder characteristics |

– ††, ‡‡Skewed FACEM population limiting validity of comparison with community data – Response rate may have introduced a selection bias |

– FACEMs had as good or better psychological health than the comparison population with moderate work stress and work satisfaction scores – Important to provide some level of working autonomy/flexibility around hours worked and activity mix – Stress identification and management (coping) should be included in ACEM training and workforce subjected to regular review | 100 |

| 6. Wrenn, Lorenzen, Jones, Zhou and Aronsky, 2010, USA | To identify factors other than work hours in the ED WE contributing to resident stress |

n = 18 postgraduate year (PGY)‐2 and PGY‐3 EM residents – Twelve surveys and questionaires were collected from each participant, four each from the day, evening and night shifts – Single site |

– Prospective cohort evaluation of stress levels – Self‐reported quantitative survey consisted of a modified version of the previously validated Perceived Stress Questionnaire normalised to a possible range of 0 to 100 and, because of the modifications, a rating of self‐perceived stress where subjects placed a mark on a 100‐mm visual analogue scale labelled ‘none’ at one end and ‘extreme’ at the other was also included – Data collected also included the shift number of a given consecutive sequence of shifts, number of procedures performed, number of adverse events, average age of the patients seen by the resident, triage nurse–assigned acuities of the patients seen by the resident during the shift, the number of patients seen during a shift, the number of patients admitted by the resident during the shift, anticipated overtime after a shift and shift‐specific metrics related to overcrowding, including average waiting room time both for the individual residents and for all patients, average waiting room count for all patients and average occupancy of the ED for all patients – Descriptive statistics and univariate analysis of data |

– The RA had no other connection to the ED, administered the survey and was the only one who knew the tracking number – RA was not involved in any sort of evaluation of residents – All investigators except the RA were blinded to the particular resident data – All 18 residents completed 100% of the surveys for a total of 216 shifts (100% response) |

– Only anticipated overtime and process failures were correlated with stress – Factors related to ED overcrowding had no significant effect on reported resident stress – EM resident shift‐specific stress was associated primarily with the perception of excessive time required to finalise or hand over patient care after the shift and with adverse events – Night shifts correlated inversely with stress – Environmental factors that reflect ED overcrowding such as high average occupancy, long LOS, long WR times and high WR counts did not seem to impact resident stress to any great degree in multivariate analysis – When overcrowding is a chronic problem, it is possible that crowding has less impact on stress because it is the norm |

– Explicit control for many workload factors – Multiple controls for bias – The survey took less than 5 min to complete |

– ‡‡Non‐probabilistic and intentional sampling based on participant availability – Timing of administration of the surveys at the end of a shift may have led some variables, such as anticipated overtime, to influence the results more than they would have if the instrument had been administered mid‐shift – An end‐of‐shift survey may also underestimate the immediate impact of stressors occurring during a shift – The findings from this small cohort of participants at a single institution providing care for a high‐acuity patient population may not generalise to other settings – Environmental stressors will vary across EDs |

– It is unlikely that solving the ED overcrowding issue will necessarily translate into less stress for the residents – In fact ‘solving’ overcrowding might increase resident stress as throughput pressure increases – Need for further research to establish generalisability of findings |

100 |

| 7. Estryn‐Behar, Doppia, Guetarni et al., 2011, France |

To examine ED physicians' perceptions of working conditions, satisfaction and health – Based around the Nurses Early eXit sTudy (NEXT project) |

Physicians – 3196 of the 4799 physicians who visited the website completed the survey; 538/3196 were ED physicians – Control sample chosen at random from database of French physicians |

– §§Quantitative online questionnaire including descriptive cross‐sectional correlational design from a self‐reported validated 260 questions exploring occupational/demographic content, private life, social WE, work organisation, work demands, individual resources and future occupational plans drawn from various previously validated surveys – Descriptive and multivariate analyses |

– Reported overall response rate: 66% |

– ¶Intention to leave was highest amongst ED physicians, particularly female physicians – Fewer meal breaks taken, fewer opportunities to teach and less frequently part of administrative hierarchy, but attended more ongoing education and worked more hours and more nights than other speciality physicians |

– Well‐matched large sample – Captured a large volume of information enabling some contextualisation of responses and good factor analysis |

– ††, ‡‡Difficult to segregate the number of ED physicians included in the final analysis – Significant questionnaire burden may reduce response rate and response accuracy – No follow up of non‐respondents to the survey |

– Many factors around ED physician retention focused around WE – These included the need to improve multidisciplinary teamwork, work processes, team training and clinical area design |

75 |

| 8. Xiao, Wang, Chen et al., 2014, China | To measure psychological distress and job satisfaction amongst Chinese emergency physicians | n = 205 ED physicians from three general hospitals |

– §§Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional design using three self‐reported surveys including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Maslach Burnout Inventory‐General Survey and Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire – Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation was used to explore data relationships |

– All the physicians from the EDs of three large general hospitals across a month were invited to participate – Response rate = 82% |

– Psychological distress is prevalent in Chinese EM physicians and they are at risk of having their mental health undermined gradually – Job satisfaction is moderate – ED physicians experienced higher levels of anxiety and depression as measured by the HADS, compared with the general population – Worsening psychological distress might partly be related to the worsening physician/patient relationship and the mistrust for doctors |

– Used well validated instruments to capture a good sample of senior ED doctors, providing a unique view of responsibilities in Chinese EDs |

– ‡‡, ††Non‐probabilistic and intentional sampling based on participant availability – Participants in the present study may fairly represent the ED physicians in city hospitals but might not be representative of those working in township health centres or private clinics |

– National healthcare administrators need to legislate regulations to forbid attacking healthcare staff, guarantee physicians resting time and increase their income – Need for further research across clinical levels and geographical regions |

75 |

Note: all survey completion was deidentified and voluntary, with appropriate accompanying ethical approval unless noted otherwise.

Data type (quantitative/qualitative) is identified in the study and/or on the basis of the analysis performed.

Note: all survey and interview data are subject to potential prevarication bias and even response falsification. Additionally, the selections required in surveys are often ‘relative’ and so can be challenging ascertain consistently and reliably (‘soft’ responses), response bias based on the psychological well‐being of participants (single point in time survey).

There were additional study findings not related to the focus of this review not reported here.

Cross‐sectional, study and thus no causal inferences can be drawn.

No provision for open‐ended responses so participants’ responses are constrained by study

MMAT classification system

ACEM, Australian College of Emergency Medicine; EM, Emergency Medicine; FACEMs, fellows of the Australasian college of emergency medicine; MD, medical doctor; MMAT, mixed methods appraisal tool; PGY, post graduate year; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; RA, research assistant; RN, registered nurse; RPPE, Revised Professional Practice Environment; SAS, statistical analysis systems; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the mean; SPSSx, statistics package for the social sciences; SSEM, Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine; SHOs, senior house officers; USA, United States; WE, work environment.

ED staff: unique population

Comparisons highlighted differences between ED staff and those working in other clinical areas, with ED staff consistently reporting higher levels of stress. However, the evidence also showed that, irrespective of the clinical population examined, ED staff self‐identify as a unique population with higher autonomy, skill base, level of team work and communication,5, 37, 38 with such factors often ameliorating the impacts of stress.10, 21, 39

Studies focused on ED nurses frequently reported different demographic profiles than other nursing populations, with a greater proportion of male staff, with advanced qualifications and longer clinical experience. However, this was culturally specific. Studies conducted in Taiwan,3 China,40 Brazil11 and Iran2 included primarily female staff populations with limited qualifications.

Studies of ED nursing staff, which reported more balanced gender populations, tended to report better social support, and job satisfaction/work engagement,38, 41, 42 while those in less diverse populations (i.e. primarily women) reported fewer positive perceptions of many aspects of working environment.2, 40 Thus, while there is cultural variability, clinical staff in EDs perceive their working environment in different ways to other groups of clinical staff. Their identified satisfaction with their work identity may protect them from some of the debilitating effects of stress in their working environment.

ED staff experience