ABSTRACT

Morphogens have been identified as guidance cues for postcrossing commissural axons in the spinal cord. Shh has a dual effect on postcrossing commissural axons: a direct repellent effect mediated by Hhip as a receptor, and an indirect effect by shaping a Wnt activity gradient. Wnts were shown to be attractants for postcrossing commissural axons in both chicken and mouse embryos. In mouse, the effects of Wnts on axon guidance were concluded to depend on the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway. Canonical Wnt signaling was excluded based on the absence of axon guidance defects in mice lacking Lrp6 which is an obligatory coreceptor for Fzd in canonical Wnt signaling. In the loss‐of‐function studies reported here, we confirmed a role for the PCP pathway in postcrossing commissural axon guidance also in the chicken embryo. However, taking advantage of the precise temporal control of gene silencing provided by in ovo RNAi, we demonstrate that canonical Wnt signaling is also required for proper guidance of postcrossing commissural axons in the developing spinal cord. Thus, axon guidance does not seem to depend on any one of the classical Wnt signaling pathways but rather involve a network of Wnt receptors and downstream components. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Develop Neurobiol 76: 190–208, 2016

Keywords: in ovo RNAi, dI1 neurons, chicken embryo, PCP pathway, Lrp5, Lrp6

INTRODUCTION

The commissural dI1 neurons of the dorsal spinal cord provide a widely used model to study molecular mechanisms of axon guidance (Chedotal, 2011; Nawabi and Castellani, 2011). Both long‐ and short‐range guidance cues directing dI1 axons to their intermediate target, the floor plate, have been characterized. Midline crossing is accompanied by a switch from attraction to repulsion, induced by changes in surface expression of guidance receptors. Both classical and nonclassical axon guidance cues contribute to postcrossing commissural axon pathfinding at the floor plate. On floor‐plate exit, postcrossing commissural axons use MDGA2 (Joset et al., 2011), SynCAMs (Niederkofler et al., 2010; Frei et al., 2014), Semaphorin6B (Andermatt et al., 2014a), and morphogen gradients to turn rostrally along the contralateral floor‐plate border (Stoeckli, 2006; Zou and Lyuksyutova, 2007). Shh, an attractant for precrossing commissural axons (Charron et al., 2003), turns into a repellent for postcrossing commissural axons due to a change in receptor expression (Bourikas et al., 2005). Instead of Boc and Patched (Okada et al., 2006), postcrossing commissural axons express Hhip (Bourikas et al., 2005). Shh itself induces the expression of Hhip, its receptor on postcrossing commissural axons, in a Glypican1‐dependent manner (Wilson and Stoeckli, 2013). In addition, Shh shapes a gradient of Wnt activity along the longitudinal axis of the spinal cord (Domanitskaya et al., 2010). Both in chicken (Domanitskaya et al., 2010) and in mouse (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003), Wnts attract postcrossing commissural axons toward the brain.

The role of Wnt ligands as axon guidance cues has been reported for a variety of neuronal populations (Aviles et al., 2013). In the absence of Wnt signaling in the mouse brainstem in Fzd3, Celsr3 (Cadherin EGF LAG seven‐pass G‐type receptor 3, a.k.a Flamingo) and Vangl2 (Van Gogh‐like protein 2) mutant mice, both ascending and descending projections are affected (Fenstermaker et al., 2010). Similarly, axon guidance along the longitudinal axis was perturbed at the spinal cord level in Celsr3 knockout mice (Shafer et al., 2011), as were many other fiber tracts (Tissir et al., 2005; Chai et al., 2014).

So far, the intracellular pathways activated in postcrossing axons on Wnt binding to Frizzled receptors have not been clearly characterized. There is evidence for the involvement of more than one of the classical Wnt signaling pathways (Aviles et al., 2013; Yam and Charron, 2013). In mice, where Wnt4 was shown to act as an attractant that promotes anterior turning of postcrossing commissural axons (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003), phosphatidylinositol‐3‐kinase (PI3K) and atypical protein kinase C signaling were shown to be required (Wolf et al., 2008). The planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway was implicated in antero‐posterior axon guidance of serotonergic and dopaminergic neurons in the brainstem and of postcrossing commissural axons in the spinal cord (Fenstermaker et al., 2010; Shafer et al., 2011). In commissural neurons Vangl2, localized to the tips of the growth cone's filopodia, regulates axon guidance by inhibiting the Dvl‐mediated phosphorylation of Fzd3. This, in turn, promotes Fzd3 endocytosis, which results in the activation of the intracellular signaling pathway (Shafer et al., 2011).

The canonical Wnt signaling pathway was ruled out for postcrossing commissural axon guidance, since mice with a mutation in Lrp6 (Low density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 6), a coreceptor for Frizzled required in the β‐Catenin‐mediated canonical Wnt pathway, did not exhibit guidance defects (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003; Wolf et al., 2008). However, because canonical Wnt signaling is crucial for early embryonic development Lrp5/6 double knockout mice could not be analyzed, as the absence of both Lrps results in very early embryonic lethality (Kelly et al., 2004). Thus, it is very likely that Lrp5, a molecule that is very similar to Lrp6, could have compensated for the loss of Lrp6 in postcrossing commissural axon guidance in Lrp6 mutant mice.

Here, we took advantage of the possibility for precise temporal control of gene silencing in the chicken embryo to show that key components of both the canonical Wnt and the PCP pathways are involved in dI1 commissural axon guidance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of in situ Probes, dsRNA, and miRNA Constructs

Probes for in situ hybridization and long double‐stranded (ds) RNA were generated by in vitro transcription from chicken expressed sequence tags [ESTs; obtained from Source BioScience LifeSciences (Nottingham, UK)] as described previously (Pekarik et al., 2003). The list of ESTs is given in Table 1. Constructs encoding miRNAs were generated as described (Wilson and Stoeckli, 2011). As negative controls, miRNA against either firefly Luciferase or chicken Wnt11 were used (Table 2).

Table 1.

ESTs Used in this Study

| Name | Target Gene | Location | GenBank Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEST817o5 | Celsr3 | base pair 3529‐4327 (ORF) of human Celsr3a | NM_001407.2 |

| ChEST908a4 | Vangl2 | 331bp 5'UTR plus base pair 1‐885 (ORF) | XM_424509.4 |

| ChEST307g18 | Prickle | base pair 306‐1058 (ORF) | XM_416036.4 |

| ChEST974e23 | Daam1 | base pair 573‐1373 (ORF) | NM_001193624.1 |

| ChEST642n19 | Lrp5 | base pair 3183‐4266 (ORF)b | NM_001012897.1 |

| ChEST996n1 | Lrp6 | base pair 1593‐2964 (ORF) | XM_417286.4 |

| ChEST231k15 | β‐Catenin | base pair 93‐886 (ORF) | NM_205081.1 |

| ChEST339L23 | Celsr1 | base pair 5243‐6238 (ORF) | XM_004934770.1 |

| ChEST766f16 | Daam2 | from base pair 2397‐3504 (ORF) plus 11 bp of the 3'UTR | XM_419476.4 |

numbers according to alignment with human CELSR3.

Lrp5 EST was cut to get two nonoverlapping fragments.

Table 2.

miRNAs Used in this Study

| Name | Target Gene | Target Sequence | Location | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miLuc | Luciferase | CGTGGATTACGTCGCCAGTCAA | ORF (1494 bp–1515 bp) | |

| miWnt11 | Wnt11 | AAGACTCATGCCTGCCTATGC | 3'‐UTR (354 bp–374 bp after stop codon) | |

| miLrp5 | Lrp5 | AAGCCAACAAGTACTATATAG | ORF (4676 bp–4696 bp) | |

| miLrp6 | Lrp6 | AAGAGCTTAACGTTCAGGAAT | ORF (3623 bp–3643bp) | Used in Fig. 4, 5,6,7 and 8 |

| miLrp6C | Lrp6 | AAGATTGATAGAGCTTCTATG | ORF (2353 bp–2373 bp) | Used in Fig. 9 |

| miLrp6H | Human LRP6 | AAGCCATTAAACGAACAGAAT | ORF (218 bp–238 bp) | Used in Fig. 9 |

| miβCat | β‐Catenin | AAACGAGGAATGCACAAGAAT | 3'‐UTR (211 bp–231 bp from stop codon) | |

| miWnt5a | Wnt5a | AAGGAATGCCAGTATCAGTTCA | ORF (319 bp–340 bp) |

Rescue Constructs

To subclone full‐length human LRP6 (LRP6FL) into the Math1‐IRES‐EGFP vector, the cDNA was obtained by PCR from the vector pCSmyc‐LRP6 (kindly provided by Dr. Giancarlo de Ferrari). XbaI and BamHI sites were introduced in the forward and reverse primers, respectively. Using these restriction sites human LRP6 was also cloned into the pMES vector.

In Situ Hybridization and Immunohistochemistry

In situ hybridization was performed on cryosections of the lumbar spinal cord of embryos sacrificed at different developmental stages (HH19‐HH25) (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951). In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Mauti et al., 2006), but without postfixation. Efficiency of downregulation was quantified as described previously (Wilson and Stoeckli, 2013).

To check whether downregulation of target genes interfered with the patterning of the spinal cord, we stained cryosections of electroporated and nontreated embryos sacrificed at stage HH23/24 for specific marker genes: Shh (5E1), Islet1 (40.2D6), Nkx2.2 (74.5A5), Hnf3β (4C7), and Pax7 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Axon growth was assessed by staining for Contactin2 (also known as Axonin‐1; rabbit anti‐Axonin1). As secondary antibody, goat anti‐mouse IgG‐Cy3 or goat anti‐rabbit IgG‐Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used.

In Ovo RNAi

All experiments involving chicken embryos were carried out according to the guidelines of the Cantonal Veterinary Office Zurich. For functional analysis of candidate genes, chicken embryos were injected and electroporated with either long dsRNA (350 ng/µL) derived from the target gene or a miRNA (500 ng/µL) as described previously (Pekarik et al., 2003; Wilson and Stoeckli, 2011, 2012; Andermatt et al., 2014b). To visualize the transfected area a plasmid encoding renilla‐GFP under the control of the β‐actin promoter (30 ng/µl) was coelectroporated with dsRNA. Because specific antibodies against chicken Wnt11 or proteins of the Wnt signaling pathways are not available, we demonstrated the efficiency of target gene silencing with fusion constructs in vitro. For this purpose, we generated constructs containing a destabilized variant of GFP (pd2EGFP, Clontech) followed by a sequence corresponding to the EST of the different target genes. These constructs driven by the β‐Actin promoter were expressed in HEK cells in the presence or in the absence of a mixture of siRNA derived from the long dsRNAs. The siRNAs were generated by enzymatic hydrolysis with ShortCut RNase III (New England Biolabs) for 20 min at 37°C, followed by phenol:chloroform extraction and LiCl/ethanol precipitation. The GFP constructs (150 ng/ml), siRNA (150 ng/mL) and a plasmid encoding the Tomato fluorescent protein (150 ng/mL) to normalize for the transfection efficiency were cotransfected into HEK cells with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Transfection with siWnt11 was used as a negative control. After 18 h, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and at least nine images were acquired per condition. The green and red fluorescence was measured using the ImageJ software and the ratio green/red fluorescence was calculated. Values for each experimental condition were normalized with the corresponding siWnt11 control (set to 100%), which did not affect the green fluorescence of any GFP construct as compared to cells not treated with siRNA. Relative expression levels after transfection with the specific siRNAs were: 0.46 ± 0.16% for siCelsr3 (p < 0.0001), 10.33 ± 2.13% for siVangl2 (p < 0.0001), 0.54 ± 0.12% for siPrickle (p < 0.0001), and 3.59 ± 1.29% for siDaam1 (p < 0.0001). Similarly, quantification of downregulation of Lrp5, Lrp6 and β‐catenin, components of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway were: 2.16 ± 0.62% for siLrp5 (p < 0.0001), 1.95 ± 0.78% for siLrp6 (p < 0.0001), 3.00 ± 1.36% for siβCat (p < 0.0001).

For rescue experiments, either control or experimental miRNA constructs (300 ng/µL) were coinjected with a Math1‐IRES‐EGFP rescue construct containing full‐length human LRP6 (700 ng/µL). Human LRP6 was not sensitive to miLrp6 which was designed to downregulate chicken Lrp6. However, human LRP6 was sensitive to a miRNA designed to target human LRP6. To test specificity we coexpressed the miRNA construct (0.5 µg/µL) and the rescue construct in the pMES vector (0.5 µg/µL) unilaterally in the embryonic chicken spinal cord. Then, EGFP expression was measured using ImageJ software.

Analysis of Postcrossing Commissural Axon Pathfinding

Electroporated and nontreated embryos were sacrificed at stage HH25/26. The spinal cord was dissected in an open‐book configuration and fixed for 30 min in 4% PFA in PBS (Perrin and Stoeckli, 2000). The dI1 commissural axons were traced by injection of the lipophilic dye DiI (5 mg/mL in ethanol; Invitrogen) into the area of the cell bodies. The phenotypes were analyzed by a person blind to the experimental condition in the GFP‐positive or EBFP‐positive area and were categorized as: normal (axons cross the floor plate and turn into the longitudinal axis along the contralateral border), ipsilateral turning (some axons turn into the longitudinal axis before crossing the floor plate), floor‐plate stalling (more than 50% of the axons fail to cross the floor plate), no turning (more than 50% of the axons that reach the contralateral floor‐plate border fail to turn into the longitudinal axis), caudal turning (some axons turn caudally instead of rostrally along the contralateral floor‐plate border). Note that caudal turns were always seen together with the no turning phenotype. DiI injection sites that were too ventral were excluded from the analysis. Only embryos with more than three injection sites were considered for the quantification. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). “N” represents the number of embryos and “n” the number of injection sites.

Statistical significance was calculated with the GraphPad Prism software using one‐way ANOVA and Dunnett's comparison test. p‐values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the analysis of the distribution of different phenotypes observed in DiI injection sites, data were subjected to two‐tailed Fisher's exact probability test (VassarStats Website ©Richard Lowry 1998–2012; http://vassarstats.net/). For statistical analyses of gene silencing mRNA signal intensities were analyzed with t‐test using the VassarStats Website.

Measurement of Canonical Wnt Activity

Canonical Wnt signaling was assessed in embryonic dorsal spinal cords by coinjection of the reporter gene that drives the expression of destabilized GFP under the control of a TCF/Lef responsive promoter at HH18/19 (Dorsky et al., 2002), together with a miRNA (EBFP‐labeled) and a plasmid encoding Tomato fluorescent protein to control for transfection efficiency. At stage HH23/24, the embryos were sacrificed and cryostat sections were imaged to quantify the GFP fluorescence and red fluorescence (Tomato) specifically in the area where commissural neurons reside. A ratio between green and red fluorescence was calculated (results are shown as mean ± SEM). At least 24 sections from 3–4 embryos were used and one‐way ANOVA was used to calculate statistic differences.

In Vitro Axon Growth Assay

Commissural neurons were dissected from embryos electroporated with a vector expressing miWnt11 (negative control), miLrp5, miLrp6 or miβCat and were plated on LabTek dishes coated with poly‐lysine and laminin (10 µg/mL each). After 15 hours in culture, the neurons were exposed to conditioned medium from cells transfected with either the empty pMES vector (control medium) or Wnt5a for 30 h before fixation and immunolabeling for the axonal marker Axonin1/Contactin2. Images were taken at random positions and axon lengths of at least 26 neurons were measured (CellM software) using a Wacom DTU‐1931 tablet and pen tool.

RESULTS

The PCP Pathway is Involved in Commissural Axon Guidance in the Chicken Embryo

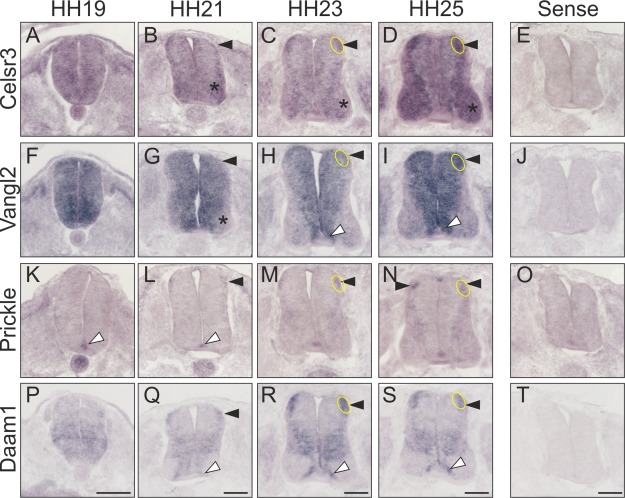

Because we previously found that Wnt5a and Wnt7a were required for postcrossing commissural axon guidance in the chicken spinal cord (Domanitskaya et al., 2010), and because components of the PCP pathway were shown to be involved in axon guidance in mouse (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003; Fenstermaker et al., 2010; Shafer et al., 2011), we assessed the expression pattern of PCP signaling components during commissural axon guidance (Fig. 1). In line with a function of PCP signaling in commissural axon guidance, we found expression of the cell‐surface molecules Celsr3 and Vangl2, as well as the intracellular components Prickle and Daam1 in dI1 neurons during axon growth toward the midline (HH19‐21), during midline crossing (HH23), and at the time of axonal turning into the longitudinal axis at the floor‐plate exit site (HH24). Expression of PCP signaling components was not restricted to dI1 neurons but also found in more ventral populations of interneurons. Vangl2 differed from Celsr3, Prickle, and Daam1, as it was expressed strongly in the ventricular zone. Most importantly for this study, Celsr3, Vangl2, and the intracellular PCP components Prickle and Daam1 were expressed in dI1 neurons at HH23 that is shortly before turning into the longitudinal axis. Expression was maintained until after the turn, as the expression patterns at HH25 did not differ from those seen at HH23.

Figure 1.

PCP pathway components are expressed in chicken dI1 commissural neurons. Transverse sections of spinal cords taken from chicken embryos at the indicated developmental stages were subjected to in situ hybridization. (A–D) Celsr3 was widely expressed in the neural tube at HH19 (A). By HH21, Celsr3 expression was mainly found in dI1 neurons (arrowhead), as well as in more ventral populations of interneurons and motoneurons (asterisk). The expression pattern was largely maintained at HH23 (C) and HH25 (D). (E) No staining was seen after hybridization with the sense probe derived from Celsr3. (F–I) Vangl2 mRNA was found throughout the neural tube at HH19 (F). A decrease of Vangl2 expression was found in motoneurons (asterisk) and mature interneurons, except dI1 neurons (arrowhead), at HH21 (G). Vangl2 expression was maintained in dI1 neurons (arrowhead) at HH23 (H) and HH25 (I). Expression of Vangl2 was also seen in the floor plate and in cells adjacent to the floor plate (white arrowhead). (J) No signal was seen with the Vangl2 sense probe. (K–N) In contrast to the cell surface molecules, the distribution of the intracellular components of the PCP pathway was much more restricted during the time window of commissural axon guidance. Prickle was found in the floor plate already at HH19 (white arrowhead, K). By HH21, Prickle expression was detectable also in dI1 neurons (arrowhead, L). Expression in dI1 neurons persisted at HH23 (M) and HH25 (N). (O) No staining was seen with a Prickle sense probe. (P–S) Daam1 was found in dI1 neurons at all stages (arrowhead). In addition, expression of Daam1 was found in cells adjacent to the floor plate (white arrowhead). (T) No staining was seen with a Daam1 sense probe. The location of dI1 commissural neurons is indicated. Scale bars: 100 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Other PCP molecules, such as Celsr1, Daam2, or Ankrd6 (ankyrin repeat domain 6, a.k.a. Diego or Diversin) were not expressed in dI1 commissural neurons at the time of midline crossing and turning into the longitudinal axis (not shown).

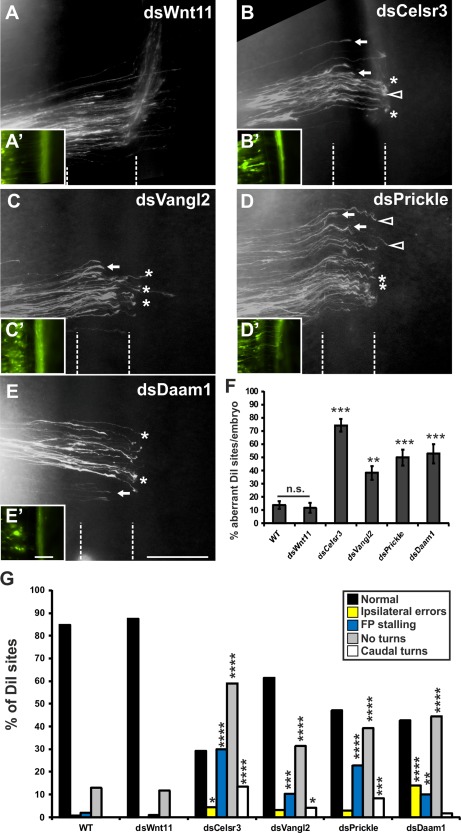

As expected based on their role in axon guidance in mouse and their expression in dI1 neurons in the chicken spinal cord, silencing PCP pathway components interfered with postcrossing commissural axon guidance (Fig. 2). dsRNA derived from the candidate genes was injected into the central canal of chicken embryos at stage HH18/19, followed by electroporation for unilateral transfection of the spinal cord. After 2 days, at stage HH25/26, the embryos were dissected and the trajectory of commissural axons was visualized by DiI injection into the area of dI1 commissural neurons in “open‐book” preparations of the spinal cord (see Materials and Methods for details). In untreated embryos, commissural axons crossed the midline and turned rostrally along the contralateral floor‐plate border. No difference was seen in control‐treated embryos injected with dsRNA derived from Wnt11 [Fig. 2(A,F)]. We used injection and electroporation of dsWnt11 as control, as Wnt11 was not expressed in the neural tube during commissural axon pathfinding (Domanitskaya et al., 2010).

Figure 2.

The PCP pathway is involved in commissural axon guidance in the chicken embryo. (A) Injection and electroporation of double‐stranded RNA derived from Wnt11 (dsWnt11) used as control had no effect on postcrossing commissural axon guidance. All axons crossed the floor plate (dashed lines) and turned rostrally. (B–F) Downregulation of the PCP pathway proteins Celsr3 (B), Vangl2 (C), Prickle (D), and Daam1 (E) interfered with axon guidance at the floor plate (F). Axons were mainly found to stall in the floor plate (arrows), failed to turn rostrally into the longitudinal axis on floor‐plate exit (asterisk) or even turned caudally (open arrowheads). (A'–E') Renilla‐GFP confirms efficient transfection. (G) Detailed analysis of the prevalence of different phenotypes. DiI injection sites with normal axonal pathfinding (black bars), ipsilateral errors (yellow bars), floor‐plate stalling (blue bars), no turning at the floor‐plate exit site (gray bars), and caudal turns (white bars) were analyzed separately. See text for details. For statistical analysis of experimental compared to control‐treated embryos we used one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's test in (F) and two‐tailed Fisher's exact test in (G). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, n.s.: not significant, the floor plate (FP) is indicated by dashed lines in A–E, A'–E'. Scale bars: 100 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

In contrast, silencing Celsr3 induced axon guidance defects at 74.4 ± 4.7% of injection sites [n = 261; N = 30; Fig. 2(B,F)]. Similarly, silencing Vangl2 caused aberrant axon pathfinding at 38.1 ± 5.2% (n = 262; N = 28) of the injection sites compared to untreated and control‐injected embryos [Fig. 2(C,F)].

The effect of the PCP pathway on commissural axon guidance was confirmed by silencing the intracellular components Prickle and Daam1 which also interfered with commissural axon guidance. Downregulation of Prickle induced aberrant phenotypes at 49.8 ± 6.0% [n = 280; N = 31; Fig. 2(D,F)] and downregulation of Daam1 at 52.7 ± 7.1% (n = 180; N = 19) [Fig. 2(E,F)] of the injection sites per embryo. In contrast, aberrant axon guidance was only found at 11.7± 3.7% (n = 127; N = 19) of the injection sites in control‐treated embryos injected and electroporated with dsWnt11 [Fig. 2(A,F)]. This was not different from untreated control embryos, where aberrant pathfinding was observed at 13.8 ± 3.0% (n = 171; N = 22) of the injection sites (not shown; Fig. 2F).

We compared the specific axon guidance phenotypes induced by silencing PCP pathway components in more detail (Fig. 2G). Downregulation of Celsr3 caused ipsilateral turning (4.2%, p = 0.019), floor‐plate stalling (29.9%, p < 0.0001), no turning (59.0%, p < 0.0001) and caudal turning (13.4%, p < 0.0001) at the contralateral floor‐plate border. In the absence of Vangl2, we found floor‐plate stalling (10.3%, p = 0.0005), no turning (31.3%, p < 0.0001), and caudal turning (4.2%, p = 0.019). Loss of Prickle function led to axonal stalling in the floor plate (22.9%, p < 0.0001), no turning (39.3%, p < 0.0001) and caudal turning at the floor‐plate exit site (8.2%, p = 0.0007). Loss of Daam1 function induced ipsilateral turning (13.9%, p < 0.0001), floor‐plate stalling (10.0%, p = 0.001) and no turning (44.4%, p < 0.0001) phenotypes. In contrast, after injection and electroporation of dsWnt11 we found very little floor‐plate stalling (0.8%) and a failure of turning into the longitudinal axis at only 11.8% of the injection sites. Ipsilateral turns or caudal turns were not found. This was virtually identical to untreated control embryos, where we found ipsilateral turning at 0.6% (p = 1.00), floor‐plate stalling at 1.8% (p = 0.638), no turning at 12.9% (p = 0.860), but also no caudal turns at any of the injection sites.

Aberrant axon guidance after silencing PCP components at HH18/19 was not due to patterning defects in the neural tube, since we found no changes in the expression of marker genes, such as Shh, Hnf3β, Islet1, Nkx2.2, or Pax7 (not shown). Similarly, the observed changes were not due to changes in neurite growth, as visualized by staining for Axonin‐1/Contactin2 (not shown). Thus, we concluded that PCP signaling was involved in postcrossing commissural axon guidance in the chicken spinal cord.

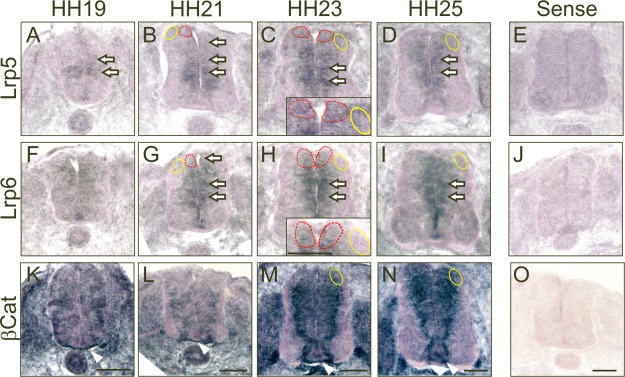

Silencing Canonical Wnt Pathway Components Leads to Defects in Commissural Axon Guidance

Despite the fact that PCP signaling was involved in postcrossing commissural axon guidance also in the chicken embryo, as found in mouse, we noticed expression of canonical Wnt signaling components during the time of axonal navigation (Fig. 3). By in situ hybridization, we detected high levels of mRNA for both Lrp5 and Lrp6 in the ventricular zone of the developing neural tube, including precursors of dI1 neurons. The signal in mature neurons was weaker especially for Lrp6. In contrast, the strong expression levels of β‐Catenin mRNA persisted in mature dI1 neurons. As shown for PCP components (Fig. 1), expression patterns of canonical Wnt signaling components were in line with a contribution to axonal growth toward the midline (HH19‐21), midline crossing (HH23), and the turn of postcrossing axons into the longitudinal axis.

Figure 3.

Components of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway are expressed in the developing chicken spinal cord during commissural axon pathfinding. Transverse sections of chicken spinal cords collected at the indicated developmental stages were subjected to in situ hybridization. (A–D) Lrp5 was found in the ventricular zone and along the periphery of the neural tube at stage HH19 (A). High expression levels were mainly found in the ventricular zone (arrows) at HH21 (B) including the area of the precursors of dI1 neurons (indicated by a dashed red line). By HH23 (C) expression was still strongest in the area of dI1 precursors (indicated by a dashed red line) but now expanded more laterally into the dorsal spinal cord, including the area of mature neurons (indicated by a yellow line). The staining pattern at HH25 (D) was very similar to the one found at HH23. No staining was seen with the sense probe derived from Lrp5 (E). (F–I) The expression pattern of Lrp6 was virtually identical. However, moderate expression of Lrp6 was found also in motoneurons at HH25 (I). No staining was obtained with the sense probe derived from Lrp6 (J). (K–N) β‐Catenin was widely found in the neural tube at stage HH19 (K) and HH21 (L). However, at stage HH23 (M) and HH25 (N) strong expression of β‐Catenin was found in the ventricular zone, especially at the border to the mantle zone. No staining was seen after hybridization with the sense probe derived from β‐Catenin (O). The area of dI1 commissural neurons is indicated by a yellow line. The area of dI1 precursors is indicated by a dashed red line. Scale bars: 100 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

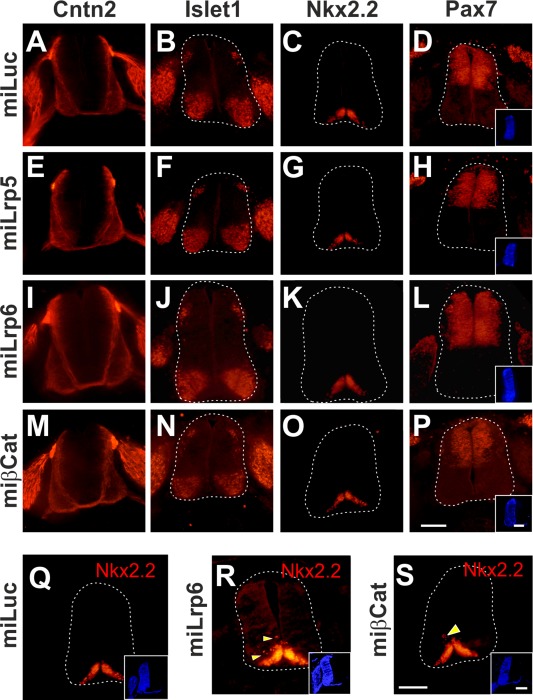

Canonical Wnt signaling contributes to early developmental processes such as gastrulation, cell differentiation and patterning, and therefore, loss‐of‐function studies with classical genetic approaches are impossible. However, we took advantage of the possibility of precise temporal control of gene silencing by in ovo RNAi (Pekarik et al., 2003; Andermatt and Stoeckli, 2014; Andermatt et al., 2014b). Early loss of canonical Wnt signaling in mouse resulted in severe patterning defects and early embryonic lethality (Muroyama et al., 2002), preventing axon guidance studies. In contrast, Wnt signaling could be blocked at E3 in chicken embryos without effect on neural tube patterning or embryonic viability, as we had shown previously (Domanitskaya et al., 2010). Silencing Wnt5a or Wnt7a did not interfere with neural tube patterning as assessed by the expression of marker genes. Similarly, silencing canonical Wnt signaling components Lrp5, Lrp6, or the intracellular component β‐Catenin at E3 did not affect neural tube patterning (Fig. 4). However, as expected, silencing canonical Wnt signaling at E2 did interfere with patterning. For instance, ectopic Nkx2.2‐positive cells were seen in embryos lacking Lrp6 (Fig. 4R) or β‐Catenin (Fig. 4S).

Figure 4.

Downregulation of canonical Wnt signaling at stage HH18/19 does not affect neural tube patterning nor interfere with commissural axon growth. Chicken embryos were injected and electroporated with dsRNA (not shown) or miRNA constructs to assess axon growth (A,E,I,M) or spinal cord patterning based on Islet1 (B,F,J,N), Nkx2.2 (C,G,K,O), or Pax7 expression (D,H,L,P). Control‐treated embryos injected with miLuc (A–D) did not differ from untreated embryos (not shown). Similarly, no changes were observed after silencing Lrp5 (miLrp5; E–H), Lrp6 (miLrp6; I–L), or β‐Catenin (miβCat; M‐P) at stage HH18/19. Embryos were analyzed at stage HH23/24. The efficiency of electroporation was demonstrated by the expression of EBFP2 (insets in D,H,L,P). Axon growth to the floor plate visualized by staining for Cntn2 (Axonin‐1) was not affected after silencing canonical Wnt signaling (E,I,M). However, when the same constructs were used to perturb Wnt signaling in younger embryos (HH12‐14), spinal cord patterning did change. In contrast to embryos injected with miLuc (Q), the silencing of Lrp6 induced ectopic Nkx2.2‐positive cells (R). Similarly, silencing β‐Catenin induced ectopic Nkx2.2 (S). Scale bars: 100 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Loss of Lrp5 function induced by transfection of dsLrp5 induced a significant increase in the percentage of injection sites with abnormal turning of postcrossing axons (46.4 ± 10.0%; n = 130; N = 17) [Fig. 5(A,H)] compared to control‐injected (dsWnt11) and untreated control embryos. Similar defects were observed after downregulation of Lrp6 at an average of 58.4 ± 7.8% of the injection sites per embryo (dsLrp6; n = 168; N = 16) [Fig. 5(B,H)]. Furthermore, silencing β‐Catenin with dsRNA induced a strong increase in the number of injections sites with axonal pathfinding errors (dsβCat; 68.3 ± 6.8%; n = 123; N = 14) [Fig. 5(C,H)].

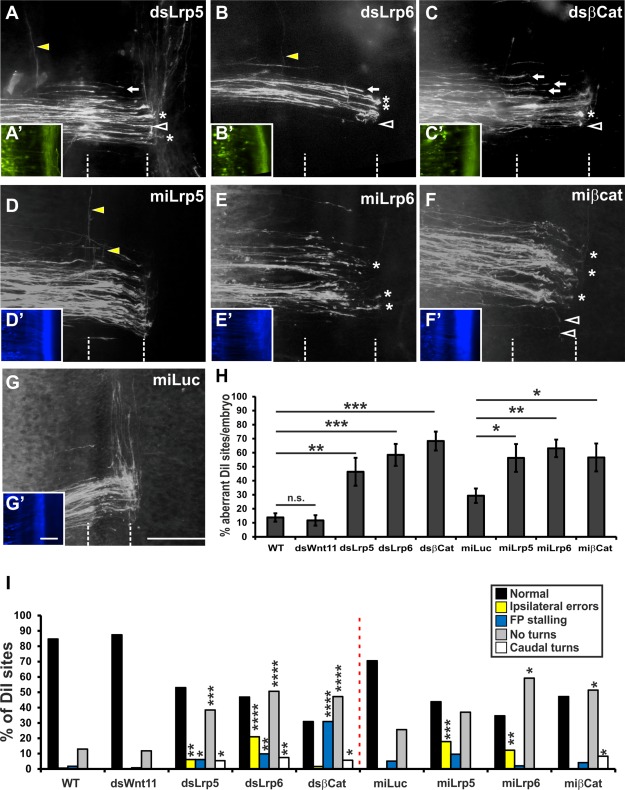

Figure 5.

Blocking canonical Wnt signaling causes defects in commissural axon guidance. Silencing canonical Wnt signaling by electroporation of dsRNA (A–C) or miRNA (D–F) resulted in aberrant commissural axon navigation at the floor plate. Downregulation of Lrp5 (A) or Lrp6 (B) with dsRNA caused pathfinding errors of commissural axons. Axons were found to turn ipsilaterally (yellow arrowheads), to stall in the floor plate (arrows), to fail turning into the longitudinal axis (asterisks), or to turn caudally (open arrowheads). (C) Loss of β‐Catenin function due to electroporation of dsβCat induced axonal stalling in the floor plate (arrows), failure to turn into the longitudinal axis (asterisks) and caudal turns of postcrossing axons (open arrowheads). (A'–C') Renilla‐GFP visualizes the efficiency of transfection with dsRNA. The pathfinding errors induced by electroporation of dsRNA were reproduced by electroporation of miRNAs targeting Lrp5 (D), Lrp6 (E), and βCatenin (F). As a control for miRNA‐induced phenotypes we used a construct containing a miRNA targeting Luciferase (miLuc; G). Axonal behavior at the floor plate in miLuc‐treated embryos was not different from untreated or dsWnt11‐treated embryos (compare to Figure 2). (D'–G') EBFP2 expressed from the miRNA constructs indicated efficient transfection. (H) Quantification of aberrant axon guidance expressed as percentage of DiI injection sites per embryo with aberrant axon guidance. Values for untreated and dsWnt11‐injected embryos were taken from Figure 2. (I) A detailed analysis of the frequency of the different phenotypes revealed similar patterns. Ipsilateral turns were only found after silencing Lrp5 and Lrp6, whereas floor‐plate stalling was more prevalent after silencing the intracellular component β‐Catenin. For statistical analysis, we used one‐way ANOVA with Dunnett's test in H and two‐tailed Fisher's exact test for values given in I. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Scale bars: 100 µm in A–G, A'–G'. The floor plate is indicated by dashed lines in A–G. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Qualitatively and quantitatively axon guidance defects obtained with miLrp5 [Fig. 5(D,H)] and miLrp6 [Fig. 5(E,H)] were very similar to those obtained with dsRNA. Silencing Lrp5 and Lrp6 with miRNA constructs caused an increase in the percentage of injection sites with aberrant navigation of commissural axons to 56.3 ± 9.9% (n = 73; N = 10) and 63.1 ± 6.3% (n = 49; N = 8) of the DiI injection sites per embryo, respectively, compared to control, miLuc‐injected embryos (29.3 ± 5.2%, n = 78; N = 12) [Fig. 5(G,H)]. Injection of a construct encoding a miRNA derived from Luciferase (miLuc) was used as a control for the miRNA‐based perturbations (Wilson and Stoeckli, 2011).

When looking at the axon guidance defects in detail (Fig. 5I), we saw that downregulation of Lrp5 with dsRNA mainly prevented axonal turning at the floor‐plate exit site (38.5% of the injection sites, p = 0.00013), but also caused ipsilateral turning (6.2%, p = 0.007), floor‐plate stalling (6.2%, p = 0.037), and caudal turning (5.4%, p = 0.014). After silencing Lrp5 with miLrp5, ipsilateral turns were found at 17.8% of the injection sites. Similarly, after downregulation of Lrp6 with dsLrp6, ipsilateral turns were observed at 21.0% of injection sites (p < 0.0001), floor plate stalling at 9.9% (p = 0.001), no turning at 50.6% (p < 0.0001) and caudal turning at 7.4% (p = 0.001) of the injection sites. Silencing with miLrp6 caused ipsilateral turns at 12.2% (p = 0.004) and no turning at 59.2% (p = 0.017) of all injection sites.

As shown for the Lrps blocking canonical Wnt signaling by silencing β‐Catenin with miβCat reproduced the phenotypes seen after transfection with dsβCat (56.6 ± 10.0% of the DiI injection sites per embryo; n = 72; N = 11). Silencing β‐Catenin with dsβCat induced floor‐plate stalling at 30.9% (p < 0.0001), no turning at 47.2% (p < 0.0001), and caudal turning at 5.7% (p = 0.01) of all injection sites (Fig. 5I). These values were similar after transfection of miβCat: axons failed to turn at the contralateral floor‐plate border at 51.4% (p = 0.042) of all injection sites and caudal turns were found at 8.3% (p = 0.028) of all injection sites compared to miLuc‐injected control embryos, where no turns were only found at 25% of all injection sites and caudal turns were never found.

Lrp Targeting is Specific

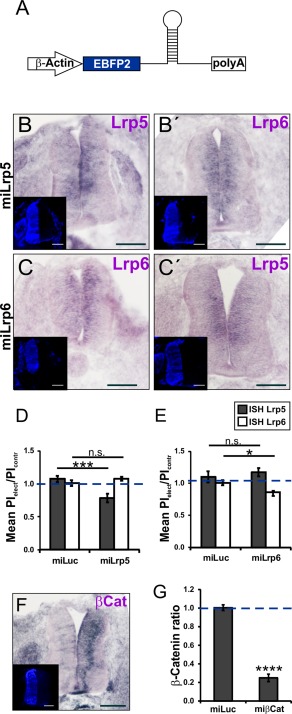

Lrp5 and Lrp6 are very similar at the protein (72% identity) and at the nucleotide sequence level (70% identity). To discriminate between the two Lrps and to confirm specificity of our approach, we tested expression of the nontargeted Lrp. As expected, silencing either Lrp5 or Lrp6 with specific miRNAs did not affect the nontargeted Lrp but still interfered with rostral turning of postcrossing commissural axons (Fig. 6). Electroporation of miLrp5 significantly reduced Lrp5 expression on the electroporated side [0.78 ± 0.07 versus 1.07 ± 0.05 in miLuc‐injected embryos, p = 0.0005; Fig. 6(B,D)] without affecting Lrp6 expre ssion [1.08 ± 0.03 versus 1.01 ± 0.04, p = 0.219; Fig. 6(B',D)]. Similarly, electroporation of miLrp6 downregulated Lrp6 [0.86 ± 0.05 versus 1.01 ± 0.04 in miLuc‐injected embryos, p = 0.027; Fig. 6(C,E)] but did not perturb Lrp5 expression [1.17 ± 0.07 versus 1.10 ± 0.09, p = 0.522; Fig. 6(C',E)].

Figure 6.

miRNAs efficiently and specifically silence the targeted gene. (A) Schematic drawing of the injected miRNA‐construct under the control of the β‐Actin promoter. The plasmid encodes EBFP2 to control for transfection efficiency. In the absence of specific antibodies, specificity and efficiency of Lrp downregulation could only be demonstrated by in situ hybridization, which is not a very suitable method for quantification. The values for gene silencing may not seem to be very high, but keep in mind that on average 60% of the cells in the targeted area are transfected. Thus, the theoretical maximum of target gene silencing is 60%, not 100%. Electroporation of a miRNA against Lrp5 (miLrp5) reduced expression of Lrp5 on the electroporated side (B) but did not affect Lrp6 expression (B'). Similarly, electroporation of a miRNA targeting Lrp6 efficiently reduced Lrp6 levels (C) without affecting Lrp5 (C'). Inserts show EBFP2 expression on the electroporated side. The ratio of the pixel intensities (PI) on the electroporated (elect) and the nonelectroporated (contr) side was calculated and compared to the value obtained for embryos injected with a miRNA directed against Luciferase (miLuc). Injection of miLrp5 (D) reduced Lrp5 levels by 22% (0.78 ± 0.07; 4 embryos, 18 sections; miLuc control 1.07 ± 0.05; 7 embryos, 34 sections) without affecting Lrp6 expression (1.08 ± 0.03; 4 embryos, 18 sections; miLuc control 1.01 ± 0.04; 4 embryos, 19 sections). Electroporation of miLrp6 (E) reduced Lrp6 levels (0.86 ± 0.05; 4 embryos, 20 sections; miLuc control 1.01 ± 0.04; 4 embryos, 20 sections), without changing Lrp5 expression (1.17 ± 0.07; 2 embryos, 12 sections; miLuc control 1.1 ± 0.09; 2 embryos, 13 sections). Electroporation of a miRNA against β‐Catenin (miβCat; F) significantly reduced the expression of β‐Catenin on the electroporated side (G; 0.25 ± 0.04; 6 embryos, 30 sections; miLuc control 1.00 ± 0.03; 5 embryos, 22 sections). t‐test for quantifications in D, E, and G. Scale bar 100 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Similarly, silencing β‐Catenin with miβCat was very effective, as the ratio (electroporated versus control side) of the signal intensity after in situ hybridization was 0.25 ± 0.04 compared to 1.0 ± 0.03 in control‐treated embryos [p < 0.0001, Fig. 6(F,G)].

Canonical Wnt Signaling Persists in Mature dI1 Neurons

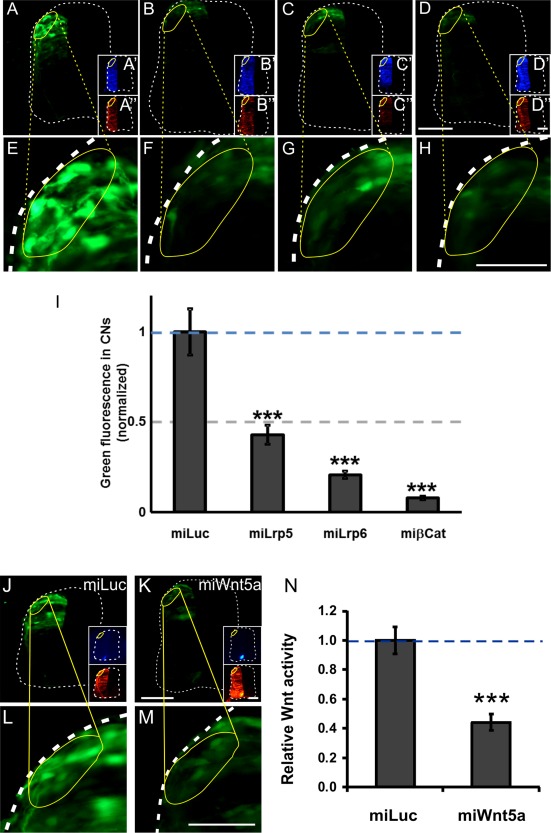

Because the mRNAs of Lrp5 and Lrp6 were clearly detected only in precursors of dI1 neurons (Fig. 3), we used a reporter assay to demonstrate that canonical Wnt signaling was indeed found in mature dI1 neurons. To this end, we expressed destabilized GFP as a reporter under the control of a TCF/Lef1/β‐catenin‐responsive promoter (Dorsky et al., 2002) (Fig. 7). GFP expression was strongly decreased after silencing Lrp5, Lrp6, or β‐Catenin. These results suggested that, even though Lrp5/6 mRNAs was not readily detectable in mature dI1 commissural neurons, the proteins persisted in mature neurons at the time when their axons cross the midline and turn into the longitudinal axis. Consistent with these findings, we found a decrease in canonical Wnt activity in dI1 commissural neurons after silencing Wnt5a in the floor plate [Fig. 7(J–N)].

Figure 7.

Canonical Wnt signaling persists in mature dI1 commissural neurons. Canonical Wnt signaling in mature dI1 neurons at the time when their axons crossed the floor plate and turned into the longitudinal axis was demonstrated by expression of GFP under the control of a TEF/Lef‐responsive promoter (A,E,I). Signaling was efficiently blocked after silencing Lrp5 (B,F,I), Lrp6 (C,G,I), or β‐Catenin (D,H,I) with miRNAs. Inserts (A'–D') show EBFP2 (enhanced blue fluorescent protein) expression indicating the successful electroporation of the miRNA constructs. Tomato fluorescence was used to normalize transfection efficiency (A“–D”). The relative GFP expression (ratio GFP/Tomato) seen in miLuc‐transfected embryos was set to 1.0 (I; 1.0 ± 0.13; 4 embryos, 27 sections). Injection and electroporation of miLrp5 reduced relative GFP expression to 0.43 ± 0.05 (4 embryos, 29 sections). Electroporation of miLrp6 resulted in GFP values of 0.21 ± 0.02 (4 embryos, 31 sections), and targeting β‐Catenin reduced GFP to 0.08 ± 0.01 (4 embryos, 31 sections). One‐way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis *** p < 0.001. Similarly, silencing Wnt5a in the floor plate resulted in a reduction of canonical Wnt signaling in dI1 neurons in vivo (J–N). Baseline canonical Wnt activity was calculated from the ratio between GFP and Tomato fluorescence in miLuc‐treated embryos (J,L; set to 1.0). After silencing Wnt5a in the floor plate (see EBFP2 expression to visualize effective targeting of the floor plate) canonical Wnt signaling was efficiently reduced (K,M,N). (N) Quantification of green fluorescence normalized by red fluorescence. t‐test, *** p < 0.001. Scale bars: 50 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

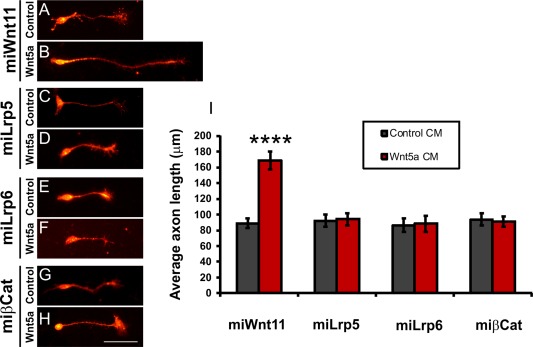

Our conclusion was further supported by results from an in vitro study, where we demonstrated that the responsiveness of commissural axons to Wnt5a is dependent on canonical Wnt signaling (Fig. 8). Wnt5a essentially doubled the length of commissural axons from control neurons [Fig. 8(B,I)]. However, Wnt5a had no effect on axonal length in the absence of canonical Wnt signaling, no matter whether this was blocked by removal of Lrp5 [Fig. 8(C,D,I)], Lrp6 [Fig. 8(E,F,I)], or βCatenin [Fig. 8(G,H,I)].

Figure 8.

Responsiveness of commissural axons to Wnt5a requires canonical Wnt signaling. Wnt5a triggered axon growth from control‐treated commissural neurons (A,B,I). However, commissural axons taken from embryos treated with miLrp5 (C,D), miLrp6 (E,F), or miβCat (G,H) were not responsive to Wnt5a (I). Commissural neurons were stained for Axonin1 (Contactin2) after 30 h of exposure to Wnt5a. Average axon length in control‐treated (miWnt11) neurons was 168.9 ± 11.8 µm after exposure to Wnt5a compared to 89.0 ± 5.9 µm when exposed to control conditioned medium, p < 0.0001. Scale bar: 50 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Canonical Wnt Signaling is Required Cell Autonomously

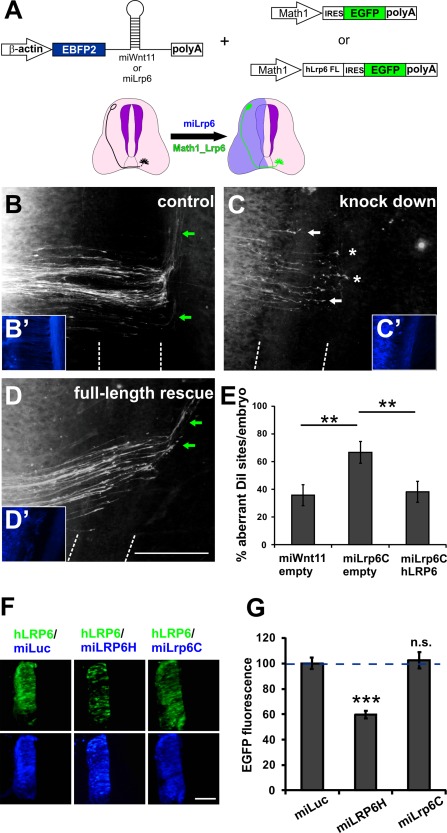

Additional evidence for a role of Lrp6 in commissural axon guidance was provided by rescue experiments. A construct containing a miRNA against Lrp6 driven by the ubiquitous β‐actin promoter was coelectroporated with a rescue construct containing human full‐length LRP6 (Mao et al., 2001) followed by IRES‐EGFP under the control of the Math1 enhancer that drives expression specifically in dI1 neurons (Fig. 9A; Wilson and Stoeckli, 2013). The rescue construct expressing human LRP6 is resistant to miLrp6 derived from chicken Lrp6 [Fig. 9(F,G)].

Figure 9.

Lrp6 is required cell‐autonomously in dI1 commissural neurons. (A) Schematic drawings of miRNA and rescue constructs. Electroporation of miLrp6C reduces endogenous Lrp6 expression in one half of the spinal cord (blue, left side in the scheme). Specific expression of human LRP6 in dI1 neurons was achieved by electroporation of human LRP6 under the control of the Math1 enhancer. Injection and electroporation of miWnt11 was used as control (B) with pathfinding errors seen at 35.7 ± 7.5% of the DiI injection sites (E; N = 11; n = 75). Expression of the miLrp6C construct to reduce endogenous Lrp6 induced axon guidance defects at 66.6 ± 7.8% of the injection sites (C,E; N = 8; n = 52). Axon guidance was rescued by expression of human LRP6 specifically in commissural neurons (D,E; N = 13; n = 90), as aberrant axon guidance was only observed at 38.8 ± 6.8% of the DiI injection sites. Human LRP6 is not targeted by miLrp6C designed against chicken Lrp6 (F,G). The ratio between the green fluorescence derived from the construct encoding human LRP6 and the blue fluorescence derived from the miRNA construct containing either miLuc or miLrp6C was used for quantification. The ratio between hLRP6 and miLuc was set to 100% (100.0 ± 4.4%). A miRNA designed against human LRP6 efficiently downregulates hLRP6 (59.5 ± 3.0%), but miLrp6C designed against chicken Lrp6 does not reduce hLRP6 (102.5 ± 6.2%). A total of 30 sections (from 5 embryos; 6 sections per embryo) per condition were quantified. We used one‐way ANOVA for statistical analysis ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n.s.: not significant. The floor plate is indicated by dashed lines in B–D. Scale bar: 100 µm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Electroporation of miLrp6 together with the empty Math1‐IRES‐EGFP vector resulted in guidance errors at 66.6 ± 7.8% of DiI injection sites [Fig. 9(C,E)] compared to 35.7 ± 7.5% in control embryos [Fig. 9(B,E)], consistent with previous results (Fig. 5). Aberrant axon guidance was rescued when embryos were coelectroporated with Lrp6FL expressed specifically in dI1 neurons [aberrant axon guidance at 38.2 ± 7.6% of DiI sites; Fig. 9(D,E)].

In summary, our results demonstrate that specific downregulation of Lrp5 or Lrp6, as well as the intracellular canonical Wnt signaling component β‐Catenin interferes with postcrossing commissural axon guidance in a cell‐autonomous manner. Taken together, our in vivo studies indicate that Wnt signaling in commissural axon guidance is complex and cannot be linked exclusively to one of the classical Wnt signaling pathways, as both canonical and PCP pathway signaling is required.

DISCUSSION

According to the classical view, Wnt proteins can bind to anyone of 10 Frizzled receptors in combination with different coreceptors and transmit a signal in one of three distinct pathways, the canonical (β‐Catenin‐dependent), the PCP, or the calcium (Ca2+)‐dependent pathway (van Amerongen and Nusse, 2009). During the last couple of years the strict separation of these pathways has been questioned due to findings in several systems. For instance, neural tube closure requires β‐Catenin‐dependent and PCP‐mediated Wnt signaling (Mulligan and Cheyette, 2012). Convergent extension in Xenopus is mediated by canonical, Ca2+, and PCP signaling (Clark et al., 2012). Similarly, the formation of the neuromuscular junction requires canonical (Wang et al., 2008) and noncanonical Wnt pathways (Henriquez et al., 2008).

It was not clear whether Wnt signaling during neural circuit formation would still involve the same components as found during morphogenesis. Observations in mouse, both in the brain and in the spinal cord, suggested that axon guidance would require the PCP pathway. The canonical Wnt signaling pathway was excluded based on the observation that Lrp6 was dispensable for correct anteroposterior navigation of postcrossing commissural axons in the mouse spinal cord (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003, Wolf et al., 2008). However, due to the requirement for Wnt signaling in very early steps of neural development, such as gastrulation, cell differentiation and neural tube patterning, Lrp6 knockout mice may not show a phenotype because of the compensatory function of Lrp5. Lrp5 and Lrp6 show high sequence similarity both at the protein and at the nucleotide level. Despite the fact that neural tube closure was defective in Lrp6 mutant mice, patterning was largely normal (Castelo‐Branco et al., 2010; Gray et al., 2013), again indicating that Lrp5 may compensate for loss of Lrp6.

Taking advantage of the possibility for precise spatial and temporal control of gene silencing in the chicken embryo by in ovo RNAi, we demonstrated that canonical Wnt signaling is involved in postcrossing commissural axon guidance, as downregulation of either Lrp5 or Lrp6 after spinal cord patterning was completed effectively perturbed axonal pathfinding at the floor plate. Obviously, in our studies, the acute knockdown of Lrp5 or Lrp6 during commissural axon pathfinding did not allow for compensation to occur. Based on our results, both Lrp5 and Lrp6 are required in commissural axon guidance. We did not observe an additive effect when downregulating both Lrp5 and Lrp6 at the same time (not shown), suggesting that both Lrps function together to transduce the Wnt signal in axon guidance.

The importance of the canonical pathway was confirmed by results obtained after downregulation of the intracellular component β‐Catenin, which was also indispensable for commissural axon guidance (Figs. 5 and 6). However, it is important to point out that this molecule is not exclusively a member of the canonical Wnt pathway. This may explain why the phenotypes observed in embryos lacking β‐Catenin are not exactly the same as those found in the absence of Lrp5 or Lrp6. Silencing β‐Catenin interfered with midline crossing more strongly than silencing Lrp5 and Lrp6. Those induced also ipsilateral turns, a phenotype that we did not observe after silencing β‐Catenin.

Evidence for involvement of several Wnt pathways in axon guidance is not only provided by the receptors. Wnt5a, one of the Wnts linked to postcrossing commissural axon guidance in mouse and chicken embryos (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2005; Domanitskaya et al., 2010; Fenstermaker et al., 2010; Shafer et al., 2011), was originally classified as a noncanonical Wnt but later found to act as a β‐Catenin‐dependent transcriptional activator depending on receptor context (Mikels and Nusse, 2006). In agreement with these findings, we demonstrated a decrease in canonical Wnt activity in dI1 commissural neurons after silencing Wnt5a in the floor plate (Fig. 7).

Taken together our studies demonstrate that Wnt signaling in axon guidance is mediated by components of both the canonical as well as the PCP pathway. Therefore, we strongly support the view put forth previously for morphogenesis that the concept of canonical versus noncanonical Wnt signaling has become obsolete (van Amerongen and Nusse, 2009). Rather Wnt signaling during neural circuit formation is mediated by a network of receptors and intracellular signaling components.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Beat Kunz and Tiziana Flego for excellent technical assistance and Dr. Giancarlo de Ferrari for providing the Lrp6 construct. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Andermatt I, Stoeckli ET. 2014. RNAi‐based gene silencing in chicken brain development. Methods Mol Biol 1082:253–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andermatt I, Wilson NH, Bergmann T, Mauti O, Gesemann M, Sockanathan S, Stoeckli ET. 2014a. Semaphorin 6B acts as a receptor in post‐crossing commissural axon guidance. Development 141:3709–3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andermatt I, Wilson N, Stoeckli ET. 2014b. In ovo electroporation of miRNA‐based‐plasmids to investigate gene function in the developing neural tube. Methods Mol Biol 1101:353–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviles EC, Wilson NH, Stoeckli ET. 2013. Sonic hedgehog and wnt: Antagonists in morphogenesis but collaborators in axon guidance. Front Cell Neurosci 7:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourikas D, Pekarik V, Baeriswyl T, Grunditz A, Sadhu R, Nardo M, Stoeckli ET. 2005. Sonic hedgehog guides commissural axons along the longitudinal axis of the spinal cord. Nat Neurosci 8:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelo‐Branco G, Andersson ER, Minina E, Sousa KM, Ribeiro D, Kokubu C, Imai K, Prakash N, Wurst W, Arenas E. 2010. Delayed dopaminergic neuron differentiation in lrp6 mutant mice. Dev Dyn 239:211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai G, Zhou L, Manto M, Helmbacher F, Clotman F, Goffinet AM, Tissir F. 2014. Celsr3 is required in motor neurons to steer their axons in the hindlimb. Nat Neurosci 17:1171–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charron F, Stein E, Jeong J, McMahon AP, Tessier‐Lavigne M. 2003. The morphogen sonic hedgehog is an axonal chemoattractant that collaborates with netrin‐1 in midline axon guidance. Cell 113:11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chedotal A. 2011. Further tales of the midline. Curr Opin Neurobiol 21:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CEJ, Nourse CC, Cooper HM. 2012. The tangled web of non‐canonical wnt signalling in neural migration. Neurosignals 20:202–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domanitskaya E, Wacker A, Mauti O, Baeriswyl T, Esteve P, Bovolenta P, Stoeckli ET. 2010. Sonic hedgehog guides post‐crossing commissural axons both directly and indirectly by regulating wnt activity. J Neurosci 30:11167–11176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsky RI, Sheldahl LC, Moon RT. 2002. A transgenic lef1/beta‐catenin‐dependent reporter is expressed in spatially restricted domains throughout zebrafish development. Dev Biol 241:229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenstermaker AG, Prasad AA, Bechara A, Adolfs Y, Tissir F, Goffinet A, Zou Y, Pasterkamp RJ. 2010. Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling controls the anterior‐posterior organization of monoaminergic axons in the brainstem. J Neurosci 30:16053–16064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei JA, Andermatt I, Gesemann M, Stoeckli ET. 2014. The SynCAM synaptic cell adhesion molecules are involved in sensory axon pathfinding by regulating axon‐axon contacts. J Cell Sci 127:5288–5302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JD, Kholmanskikh S, Castaldo BS, Hansler A, Chung H, Klotz B, Singh S, Brown AMC, Ross ME. 2013. Lrp6 exerts non‐canonical effects on wnt signaling during neural tube closure. Hum Mol Genet 22:4267–4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. 1951. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J Morphol 88:49–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriquez JP, Webb A, Bence M, Bildsoe H, Sahores M, Hughes SM, Salinas PC. 2008. Wnt signaling promotes AChR aggregation at the neuromuscular synapse in collaboration with agrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:18812–18817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joset P, Wacker A, Babey R, Ingold EA, Andermatt I, Stoeckli ET, Gesemann M. 2011. Rostral growth of commissural axons requires the cell adhesion molecule mdga2. Neural Dev 6:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly OG, Pinson KI, Skarnes WC. 2004. The wnt co‐receptors lrp5 and lrp6 are essential for gastrulation in mice. Development 131:2803–2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Shi J, Lu CC, Wang ZB, Lyuksyutova AI, Song XJ, Zou Y. 2005. Ryk‐mediated wnt repulsion regulates posterior‐directed growth of corticospinal tract. Nat Neurosci 8:1151–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyuksyutova AI, Lu CC, Milanesio N, King LA, Guo N, Wang Y, Nathans J, Tessier‐Lavigne M, Zou Y. 2003. Anterior‐posterior guidance of commissural axons by Wnt‐frizzled signaling. Science 302:1984–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao B, Wu W, Li Y, Hoppe D, Stannek P, Glinka A, Niehrs C. 2001. LDL‐receptor‐related protein 6 is a receptor for dickkopf proteins. Nature 411:321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauti O, Sadhu R, Gemayel J, Gesemann M, Stoeckli ET. 2006. Expression patterns of plexins and neuropilins are consistent with cooperative and separate functions during neural development. BMC Dev Biol 6:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikels AJ, Nusse R. 2006. Purified Wnt5a protein activates or inhibits beta‐catenin‐TCF signaling depending on receptor context. PLoS Biol 4:e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan KA, Cheyette BNR. 2012. Wnt signaling in vertebrate neural development and function. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 4:774–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroyama Y, Fujihara M, Ikeya M, Kondoh H, Takada S. 2002. Wnt signaling plays an essential role in neuronal specification of the dorsal spinal cord. Genes Dev 16:548–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawabi H, Castellani V. 2011. Axonal commissures in the central nervous system: How to cross the midline? Cell Mol Life Sci 68:2539–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederkofler V, Baeriswyl T, Ott R, Stoeckli ET. 2010. Nectin‐like molecules/SynCAMs are required for post‐crossing commissural axon guidance. Development 137:427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada A, Charron F, Morin S, Shin DS, Wong K, Fabre PJ, Tessier‐Lavigne M, McConnell SK. 2006. Boc is a receptor for sonic hedgehog in the guidance of commissural axons. Nature 444:369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekarik V, Bourikas D, Miglino N, Joset P, Preiswerk S, Stoeckli ET. 2003. Screening for gene function in chicken embryo using RNAi and electroporation. Nat Biotechnol 21:93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin FE, Stoeckli ET. 2000. Use of lipophilic dyes in studies of axonal pathfinding in vivo. Microsc Res Tech 48:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer B, Onishi K, Lo C, Colakoglu G, Zou Y. 2011. Vangl2 promotes wnt/planar cell polarity‐like signaling by antagonizing Dvl1‐mediated feedback inhibition in growth cone guidance. Dev Cell 20:177–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckli ET. 2006. Longitudinal axon guidance. Curr Opin Neurobiol 16:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissir F, Bar I, Jossin Y, Backer Od, Goffinet AM. 2005. Protocadherin celsr3 is crucial in axonal tract development. Nat Neurosci 8:451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Amerongen R, Nusse R. 2009. Towards an integrated view of wnt signaling in development. Development 136:3205–3214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ruan NJ, Qian L, Lei Wl, Chen F, Luo ZG. 2008. Wnt/beta‐catenin signaling suppresses rapsyn expression and inhibits acetylcholine receptor clustering at the neuromuscular junction. J Biol Chem 283:21668–21675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NH, Stoeckli ET. 2011. Cell type specific, traceable gene silencing for functional gene analysis during vertebrate neural development. Nucleic Acids Res 39:e133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, NH , Stoeckli, ET . 2012. In ovo electroporation of miRNA‐based plasmids in the developing neural tube and assessment of phenotypes by DiI injection in open‐book preparations. J Vis Exp 68:e4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NH, Stoeckli ET. 2013. Sonic hedgehog regulates its own receptor on postcrossing commissural axons in a glypican1‐dependent manner. Neuron 79:478–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf AM, Lyuksyutova AI, Fenstermaker AG, Shafer B, Lo CG, Zou Y. 2008. Phosphatidylinositol‐3‐kinase‐atypical protein kinase C signaling is required for wnt attraction and anterior‐posterior axon guidance. J Neurosci 28:3456–3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam PT, Charron F. 2013. Signaling mechanisms of non‐conventional axon guidance cues: The shh, BMP and wnt morphogens. Curr Opin Neurobiol 23:965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, Lyuksyutova AI. 2007. Morphogens as conserved axon guidance cues. Curr Opin Neurobiol 17:22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]