The adult mammalian heart is composed of many cell types, the most abundant being cardiomyocytes (CMs), fibroblasts (FBs), endothelial cells (ECs), and peri-vascular cells. CMs occupy ~70–85% of the volume of the mammalian heart.1–4 Although non-myocytes occupy a relatively small volume fraction, they are essential for normal heart homeostasis, providing the extracellular matrix, intercellular communication, and vascular supply needed for efficient cardiomyocyte contraction and long-term survival. Both myocytes and non-myocytes respond to physiological and pathological stress, and maladaptive changes in non-myocytes, such as cardiac fibrosis or reduced capillary density, participate in the pathogenesis of heart failure.

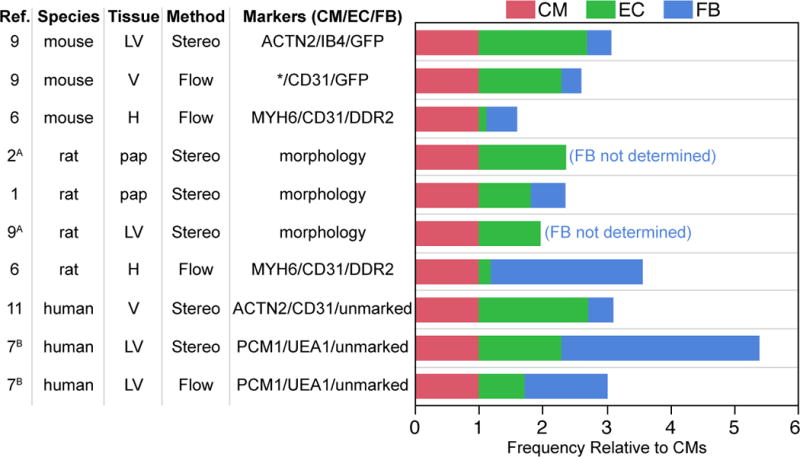

Despite the importance of non-myocytes in cardiac health and disease, there are fundamental gaps in our knowledge about them. For instance, while there has been general consensus that CMs constitute 30–40% of the cells in the mammalian heart,5–10 estimates of the frequency of ECs and FBs have differed substantially (Figure). Inadequate tools and lack of reliable markers for FBs have contributed to this uncertainty. In this issue of Circulation Research, Pinto and colleagues9 revisit the question of the cellular composition of the modern heart using modern techniques and reagents. In doing so they validate a useful new cell surface marker for cardiac FBs which may prove broadly useful to cardiac biologists.

Figure. Cellular composition of the mammalian heart.

Summary of studies that have measured the proportion of cardiomyocytes (CMs), endothelial cells (ECs), and fibroblasts (FBs) in the heart, using either stereology or flow cytometry. To allow comparison between studies, results are expressed as relative proportions of cells, with CMs assigned a value of one. Where numbers of CM nuclei were measured, cell number was not corrected for multinucleation. Additional assumptions used are noted by superscript letters: A, CM volume is 25 times that of ECs or fibroblasts; B, cells not stained by EC or CM antibodies were fibroblasts. LV, left ventricle. V, ventricles. H, whole heart. pap, papillary muscle. *, fraction of CMs not measured and based on stereology study in same reference.

Several investigators have used stereological methods to estimate the volume fraction of the heart occupied by its major constituent cell types.1–4,11 In rat or human heart sections imaged by light microscopy, the volume fraction occupied by CMs, ECs, and interstitial cells was 70–80%, 3.2–5.3%, and 1.4–1.9%, respectively. 1–3,11 Since the mean volume of CMs is 20–25 times that of ECs or FBs, 1,2 this leads to an estimated proportion of ECs to CMs of 0.8–1.9 and FBs to CMs of 0.4–0.7, i.e. based on these studies, ECs are among the most abundant cell types in the heart, whereas FBs are two to three-fold less abundant (Figure).

Heart dissociation followed by immunostaining and flow cytometric analysis has also been used to measure the cellular composition of the heart. Using this strategy, Bannerjee and colleagues evaluated the composition of the mouse and rat heart, marking CMs, ECs, and fibroblasts with antibodies to MHCa, CD31, and DDR2, respectively.6 These investigators concluded that the rat heart comprises 30% CMs, 6% ECs, and 64% FBs. Application of the same technique to mouse hearts suggested that ECs were also a minor cell population (6%) in that species as well. Interestingly, the authors found that CMs were more abundant in the mouse heart (54%), with correspondingly less FBs (26%). The study suggested that cardiac cellular composition may vary significantly between species, although the proportion of CMs measured in the mouse heart is higher than reported in most other studies.8–10

Recently, Bergmann et al. analyzed the cellular composition of human hearts by both stereological and flow cytometric methods.7 The authors marked CM nuclei with PCM1 and ECs with lectin Ulex Europaeus Agglutinin I (UEA), while unmarked cells (UEA− PCM1−) were classified as mesenchymal. Stereological analysis of histological sections estimated the frequency of CM, EC, and mesenchymal populations at 18%, 24%, and 58%, respectively, while flow cytometry of isolated cell nuclei estimated frequencies of 33%, 24%, and 43%, respectively. Thus, assuming the most mesenchymal cells are fibroblasts, the Bergmann study on human hearts generally corroborated Bannerjee’s report6 that FBs are the predominant cardiac cell type (presuming that most mesenchymal cells are FBs).

Making sense of these divergent conclusions requires understanding the relative strengths and weaknesses of the techniques used. Flow cytometry is objective, quantitative, and does not suffer from sampling bias. However, the cell dissociation step is critical, and biased recovery of cell types (for example, due to excessive cell death, or incomplete cell dissociation) could strongly influence results. Cell dissociation also destroys morphological and positional information that can assist in identifying cell types. Stereological approaches avoid potential dissociation artefacts, and can incorporate cell position and morphology in cell type identification. However, these histological approaches are often labor intensive, unfamiliar to molecular biologists, and vulnerable to sampling bias. Furthermore, identifying cells solely by morphological information is subjective and prone to error. Both flow cytometry and more recent histological studies rely selective labeling of desired cell populations, either using antibodies or genetic labels. Molecular markers or the antibodies used to detect them may be non-specific, or alternatively may incompletely label a desired cell type. Thus the reliability of the reagents and techniques used to classify cells is critical to the interpretation of the experimental data.

Pinto and colleagues reassessed the cellular composition of the heart by both histology-based and flow cytometric methods.9 The study incorporated several refinements that make it the most definitive quantification of the cellular composition to date: (1) the study used three independent genetically encoded markers of cardiac fibroblasts (PDGFRαGFP, Col1a1-GFP, and Tcf21MerCreMer; Rosa26tdTomato). The PDGFRαGFP and Col1a1-GFP expressing cardiac cell populations overlap to a remarkable degree, suggesting that they each label most cardiac FBs. These reagents are the best current means to identify cardiac fibroblasts12,13. In comparison, previously used markers such as DDR2, Thy2, CD90, and Sca-1 are less sensitive and less specific. (2) Cell dissociation was optimized to recover non-myocytes, rather than to yield viable myocytes. (3) Cells analyzed by flow cytometry were gated viable, nucleated cells, limiting technical artefacts arising from cell debris. (4) Multi-parametric flow cytometry data was analyzed using an unbiased clustering algorithm, SPADE,14 to identify phenotypically similar groups of cells based on signals from multiple markers.

The study found that 32% of all nuclei in the murine heart belonged to CMs (sarcomeric α-actinin), 55% to ECs (nuclei within isolectin B4 (IB4) outlines), and 13% to FBs (GFP+ in PDGFRαGFP or Col1a1-GFP mice).9 ECs were similarly abundant in human heart sections. For both species the abundance of ECs was confirmed using the EC marker DACH1. The abundance of ECs compared to FBs was further independently validated by flow cytometry of the non-myocyte fraction of murine hearts, followed by SPADE analysis. Of non-myocytes, 64% were ECs (CD31+ CD45−), 27% were mesenchymal cells (CD31− CD45−), and 9% were leukocytes (CD45+). The identity of the ECs was further validated by their co-expression of either vascular endothelial cell (CD102+ CD105+; 94%) or lymphatic endothelial cell (podoplanin+; 5%) markers. About 55% of mesenchymal cells expressed GFP in PDGFRαGFP or Col1a1-GFP mice, supporting their identity as FBs. Thus, the estimates of EC and FB abundance in the heart by histology (55% and 13%, respectively) agreed fairly well to those obtained by flow cytometry (44% and 10%, respectively). Interestingly, these estimates also agree with the relative ratios of CMs, ECs, and FBs estimated from initial histological observations made more than thirty years ago.1–3,5,11

Having identified cardiac fibroblasts by flow cytometry, the authors were able to screen for antibodies that could reliably identify them. Neither CD90 nor Sca-1 were sensitive or specific markers, compared to GFP in either PDGFRαGFP or Col1a1-GFP mice. Importantly, the authors found that the antibody MEFSK4 labeled cardiac fibroblasts with high specificity (87%) and sensitivity (97%), when using GFP in PDGFRαGFP/Col1a1-GFP double transgenic mice as the (admittedly imperfect) “gold standard”. MEFSK4 is a monoclonal rat antibody developed to immunodeplete murine embryonic feeders from stem cell cultures. This non-genetic cell surface marker of murine cardiac fibroblasts will be very useful for studies of cardiac fibrosis. However, the antibody has some limitations. It does not appear to work for immunostaining, and the protein bound by the antibody has not been described. As noted by Pinto et al., subsets of NG2+ mesenchymal cells and CD11b+ leukocytes are also labeled by MEFSK4. The antibody binds to MEFs from several strains of mice, so it is likely to label cardiac fibroblasts across mouse strains. However, its usefulness in rats (the host species) or in humans has not been established. Greater experience with MEFSK4 will be needed to determine how well it marks cardiac FBs at different developmental stages or under different pathological contexts.

With the reagents and techniques established by Pinto et al.9 to label and quantify the major non-myocyte populations of the murine heart in hand, we are better positioned to understand how these cell populations participate in cardiac growth, homeostasis, and disease. During heart development, endothelial cells powerfully influence cardiac morphogenesis and function. The abundance of ECs in the adult heart and their proximity to cardiomyocytes positions them to critically regulate adult heart function and response to pathophysiological stress. Although cardiac FBs may not be as abundant in the normal adult heart as some have previously argued, they nevertheless are important support cells for cardiomyocytes and play central roles in cardiac fibrosis, adverse remodeling, and arrhythmogenesis. Lack of reliable cardiac fibroblast markers has long hampered the study of cardiac FBs, and the work of Pinto et al. partially overcomes this hurdle.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

WTP was supported by the AHA and by the NIH (HL094683 and HL116461).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Anversa P, Olivetti G, Melissari M, Loud AV. Stereological measurement of cellular and subcellular hypertrophy and hyperplasia in the papillary muscle of adult rat. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 1980;12(8):781–795. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(80)90080-2. Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dämmrich J, Pfeifer U. Cardiac hypertrophy in rats after supravalvular aortic constriction. Virchows Archiv B. 1983;43(1):265–286. doi: 10.1007/BF02932961. Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattfeldt T, Krämer K-L, Zeitz R, Mall G. Stereology of myocardial hypertrophy induced by physical exercise. Virchows Archiv A. 1986;409(4):473–484. doi: 10.1007/BF00705418. Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang Y, Nyengaard JR, Andersen JB, Baandrup U, Gundersen HJ. The application of stereological methods for estimating structural parameters in the human heart. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2009;292(10):1630–47. doi: 10.1002/ar.20952. United States. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nag AC. Study of non-muscle cells of the adult mammalian heart: a fine structural analysis and distribution. Cytobios. 1980;28(109):41–61. ENGLAND. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee I, Fuseler JW, Price RL, Borg TK, Baudino TA. Determination of cell types and numbers during cardiac development in the neonatal and adult rat and mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293(3):H1883–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00514.2007. United States. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergmann O, Zdunek S, Felker A, Salehpour M, Alkass K, Bernard S, Sjostrom SL, Szewczykowska M, Jackowska T, Dos Remedios C, Malm T, Andrä M, Jashari R, Nyengaard JR, Possnert G, Jovinge S, Druid H, Frisén J. Dynamics of Cell Generation and Turnover in the Human Heart. Cell. 2015;161(7):1566–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.026. United States. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh S, Ponten A, Fleischmann BK, Jovinge S. Cardiomyocyte cell cycle control and growth estimation in vivo–an analysis based on cardiomyocyte nuclei. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86(3):365–73. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto AR, Ilinykh A, Ivey MJ, Kuwabara JT, D’Antoni M, Debuque RJ, Chandran A, Wang L, Arora K, Rosenthal N, Tallquist MD. Revisiting Cardiac Cellular Composition. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307778. [in this issue] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raulf A, Horder H, Tarnawski L, Geisen C, Ottersbach A, Röll W, Jovinge S, Fleischmann BK, Hesse M. Transgenic systems for unequivocal identification of cardiac myocyte nuclei and analysis of cardiomyocyte cell cycle status. Basic Res Cardiol. 2015;110(3):33. doi: 10.1007/s00395-015-0489-2. Germany. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anversa P, Loud AV, Giacomelli F, Wiener J. Absolute morphometric study of myocardial hypertrophy in experimental hypertension. II. Ultrastructure of myocytes and interstitium. Lab Invest. 1978;38(5):597–609. UNITED STATES. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acharya A, Baek ST, Huang G, Eskiocak B, Goetsch S, Sung CY, Banfi S, Sauer MF, Olsen GS, Duffield JS, Olson EN, Tallquist MD. The bHLH transcription factor Tcf21 is required for lineage-specific EMT of cardiac fibroblast progenitors. Development. 2012;139(12):2139–49. doi: 10.1242/dev.079970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore-Morris T, Guimarães-Camboa N, Banerjee I, Zambon AC, Kisseleva T, Velayoudon A, Stallcup WB, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Cedenilla M, Gomez-Amaro R, Zhou B, Brenner DA, Peterson KL, Chen J, Evans SM. Resident fibroblast lineages mediate pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(7):2921–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI74783. United States. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu P, Simonds EF, Bendall SC, Gibbs KD, Bruggner RV, Linderman MD, Sachs K, Nolan GP, Plevritis SK. Extracting a cellular hierarchy from high-dimensional cytometry data with SPADE. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(10):886–91. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1991. United States. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]