Abstract

Background

Airway inflammation, mediated in part by LTB4, contributes to lung destruction in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). LTB4-receptor inhibition may reduce airway inflammation. We report the results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of the leukotriene B4 (LTB4)-receptor antagonist BIIL 284 BS in CF patients.

Methods

CF patients age ≥ 6 years with mild to moderate lung disease were randomized to oral BIIL 284 BS or placebo once daily for 24 weeks. Co-primary endpoints were change in FEV1 and incidence of pulmonary exacerbation.

Results

After 420 (155 children, 265 adults) of the planned 600 patients were randomized, the trial was terminated after a planned interim analysis revealed a significant increase in pulmonary related serious adverse events (SAE) in adults receiving BIIL 284 BS. Final analysis revealed SAEs in 36.1% of adults receiving BIIL 284 BS vs. 21.2% receiving placebo (p=0.007), and in 29.6% of children receiving BIIL 284 BS vs. 22.9% receiving placebo (p= 0.348). In adults, the incidence of protocol-defined pulmonary exacerbation was greater in those receiving BIIL 284 BS than in those receiving placebo (33.1% vs. 18.2% respectively; p=0.005). In children, the incidence of protocol-defined pulmonary exacerbation was 19.8% in the BIIL 284 BS arm, and 25.7% in the placebo arm (p=0.38).

Conclusions

While the cause of increased SAEs and exacerbations due to BIIL 284 BS is unknown, the outcome of this trial provides a cautionary tale for the administration of potent anti-inflammatory compounds to individuals with chronic infections, as the potential to significantly suppress the inflammatory response may increase the risk of infection-related adverse events.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, clinical trial, lung disease, anti-inflammatory therapy, leukotriene B4 receptor antagonist

INTRODUCTION

In the cystic fibrosis (CF) lung, persistent infection, particularly by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, drives excessive and persistent polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) infiltration, leading to irreversible lung destruction and early death [1–3]. Recognition that the products of chronic inflammation are harmful to the CF lung has resulted in strategies to reduce lung infection [4] and the damage associated with chronic inflammation [5,6].

Several approaches have been studied in an attempt to limit inflammation-mediated lung damage in patients with CF [7]. To date, only high-dose ibuprofen, with a broad-based anti-inflammatory mechanism of action, has been shown to be effective [8–10], but this therapy has not been widely adopted by CF clinicians [11]. An alternative approach to reducing chronic inflammation is to use a more targeted anti-inflammatory approach directed at known neutrophil chemoattractants in the CF lung.

LTB4, produced by macrophages and PMNs in response to various stimuli, including P. aeruginosa [12], is a potent chemoattractant for and activator of PMNs [13], and along with IL-8 is considered to play a significant role in recruitment of PMNs into CF airways [7]. Thus, inhibiting the action of LTB4 using an LTB4 receptor antagonist may be beneficial in the treatment of CF lung disease. There is strong preclinical evidence to support the potential for clinical efficacy of LTB4 receptor antagonists in CF including: high levels of LTB4 in CF sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [14,15], correlation between levels of LTB4 in the CF airway and reductions in pulmonary function [16], and preliminary evidence in CF patients of clinical efficacy with eicosanoid modulators such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) [17].

BIIL 284 BS is under development as an LTB4 receptor antagonist for treating inflammation for a variety of medical conditions. BIIL 284 BS is a prodrug that is converted in vivo to active glucuronidated metabolites BIIL 260 and BIIL 315, both of which have been reported to have high affinities to the LTB4 receptor on isolated human neutrophil cell membranes [18]. BIIL 284 BS has been shown to significantly inhibit LTB4-induced mouse ear inflammation and monkey neutropenia [18]. Following satisfactory results from two phase Ib trials evaluating the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of up to 15 days treatment with BIIL 284 BS in subjects with CF [19, 20], we conducted a 24 week multi-centre, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial (Boehringer Ingelheim 543.45) of the safety and efficacy of BIIL 284 BS in patients with CF [21].

METHODS

This randomized double blind, placebo controlled trial was conducted during the years 2003 to 2004 at 61 sites in 8 countries (Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, The Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States) in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional review boards approved the study for each site and all patients or their guardians provided written informed consent before any study procedures were performed.

To be enrolled in the study, males and females ≥6 years of age had to have a documented CF diagnosis, have a body weight of ≥20 kg, be able to reproducibly perform spirometry [22], and have forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) ranging from 25% to 85% of their predicted value based on age, sex, and height. In addition, adults (≥ 18 years of age) with FEV1 > 85% predicted and current Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection were also eligible. FEV1 % predicted was calculated using the reference equations of Wang et al. [23] for subjects ≤18 years of age and of Knudson et al. [24] for older subjects. In addition, subjects were required to have been clinically stable (no evidence of acute symptoms of upper or lower respiratory tract infection) and not have received intravenous (IV), oral or inhaled antibiotics or oral corticosteroids for treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation within the 4 weeks preceding screening. Finally, subjects were required to have an FEV1 within 10% of their screening FEV1 at Day 0 and to agree to continue taking any chronic medications they were currently receiving for the duration of the study. Individuals were excluded from study participation if they had persistent Burkholderia cepacia complex lung infection or were treated chronically with oral corticosteroids or high-dose ibuprofen to control lung inflammation.

After screening (Day −14), subjects were randomized to each treatment within each age group and study site in a ratio of 1:1 for 75 mg active drug or placebo in pediatric subjects (6 to 17 years of age) and in a ratio of 1:1:2 for 75 mg active drug, 150 mg active drug, or placebo in adults (≥18 yr), respectively. Treatment was initiated at Day 0 (baseline) and subjects were monitored every 28 days until end of treatment (Day 168; 24 weeks). A follow-up visit was scheduled 28 days after end of treatment (Day 196). Trial medication was dispensed at each study visit and unused tablets were collected before new medication was dispensed to assess compliance.

Primary efficacy endpoints were change in FEV1 % predicted from baseline and the proportion of subjects experiencing a pulmonary exacerbation during the treatment period using the Fuchs criteria [25]. Symptom changes associated with the Fuchs criteria were captured via the Respiratory and Systemic Symptoms Questionnaire (RSSQ) at each study visit [26]. The Fuchs criteria include treatment with intravenous antibiotics to meet the definition of a pulmonary exacerbation. Secondary efficacy endpoints included change in forced vital capacity (FVC) % predicted from baseline, time to pulmonary exacerbation, proportion of patients receiving IV antibiotics, time to IV antibiotic use, proportion of patients hospitalized, and time to hospitalization. Adverse event monitoring was assessed at each visit. Blood and urine sampling was also included to assess for safety, and included complete blood counts with differential among other laboratory tests. Oversight of the trial was performed by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB); a Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), which was a subcommittee of the DSMB, served as the review committee for the trial. The DMC consisted of 3 physicians experienced in treating CF and a biostatistician. Safety data was monitored by the DMC members on a continual basis throughout the trial, using a web-based data entry system. Based on projected enrolment rates, the first DMC review was planned to take place when 50% of the subjects had been randomized; if 50% enrollment had not been achieved by 6 months of trial initiation, a review of existing data was to be performed by the DMC at that time. Further DMC reviews were to take place at regular intervals thereafter until completion of the study (i.e. Last Patient Out). In addition to the regularly scheduled reviews, there was also provision for ad hoc reviews, if deemed necessary by the DMC or by the sponsor. The DMC could recommend early termination of the study for reasons of patient safety based on the interim review of this safety data.

The DMC reviews were focused on safety, with no formal analysis of efficacy or futility of the primary endpoints. A comprehensive, unblinded interim safety report was generated for all members of the DMC to review. Adverse events were tabulated by body system, intensity, seriousness and their relationship to the study drug. Abnormal changes in laboratory values were summarized. All available pulmonary function data was summarized for the DMC review for the purpose of evaluating the safety of BIIL 284 BS. The report was accompanied by listings of adverse events and other safety data by subject. SAEs were monitored by the DMC in real time throughout the trial. SAEs were required to be reported by the Investigator to the sponsor with 24 hours of learning of the event. The sponsor then sent the SAE report via fax to the DMC Chair.

A sample size of 600 patients was planned (300 each in the pediatric and adult group) in order to provide >90% power to detect a difference of a 3% predicted change from baseline in FEV1 between placebo and active treatment assuming a standard deviation of 11% predicted in each treatment group and a two-sided level α =0.05 test. This sample size was also determined to provide 80% power to detect a difference in exacerbation incidence between the two treatment arms assuming a 30% exacerbation incidence in the placebo group and a 20% incidence in the BIIL 284 BS group by chi-squared test (α=0.05). Proportions were compared using a two-sided chi-squared test, and Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank test were used for comparing time to pulmonary exacerbation. Independent t-test was used to compare change from baseline in spirometry measures and other clinical and laboratory endpoints. Because of the potential bias incurred by early termination of the study on estimation and testing, p-values are reported for descriptive purposes.

RESULTS

The first subject enrolled in the trial on May 20, 2003. The first formal DMC review took place on October 29, 2003; the DMC recommended to “proceed with study conduct”. A second formal DMC review took place on February 18, 2004; the DMC recommended again to “proceed with study conduct”. Before the next scheduled formal DMC review, additional data was requested based on the real-time ongoing reviews of SAEs. After reviewing this data, the DMC requested a meeting with the sponsor to discuss a potential safety issue. Because the data being discussed were unblinded, only two internal sponsor personnel were involved: a statistician independent from the trial and the project leader. Termination of the trial was recommended by the DMC on May 13, 2004 and the lead monitor was notified. Investigators, site staff and local monitors were notified on May 14, 2004 and the trial was terminated. All subjects were contacted immediately and instructed to discontinue their study medication and return to their study site as soon as possible for a final evaluation visit.

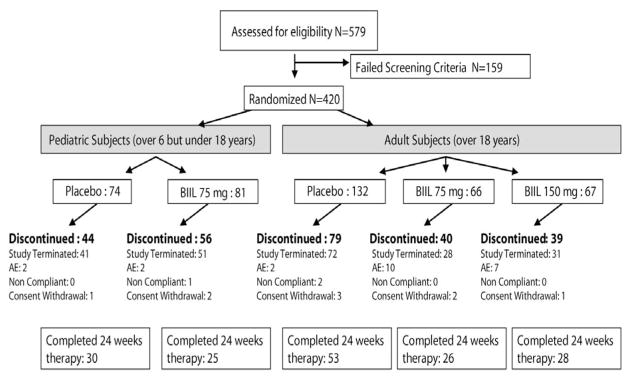

Of 579 eligible individuals screened, 420 were enrolled in the trial. The planned target enrollment of 600 was not achieved due to early termination of the trial; a significant proportion of subjects were classified as screen failures as a direct consequence of the early trial termination. A majority of randomized subjects (258; 61.4%) were discontinued from the study, with 223 discontinuations due to safety concerns by the DMC and the sponsor related to BIIL 284 BS. Other reasons for discontinuation were adverse events (23), withdrawal of consent (9) and non compliance (3). The remaining 162 subjects (38.6%) completed the entire 24 weeks of treatment (Fig. 1). Baseline subject characteristics, including mean age, FEV1 % predicted, weight, and lung infection status were well balanced between the pediatric and adult treatment arms (Table 1). Pediatric subjects received BIIL 284 BS for a median of 102 days versus 114 days for those receiving placebo. Adults received BIIL 284 BS (pooled groups) for a median of 149 days versus 151 days for those receiving placebo. Study drug compliance ranged between 92 and 98% for each study arm.

Figure 1.

Subject Disposition, Consort Diagram

Table 1.

Subject Demographics and Baseline Characteristics*

| Characteristic | Ped Placebo (N=74) | Ped 75 mg (N=81) | Adult Placebo (N=132) | Adult 75 mg (N=66) | Adult 150 mg (N=67) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age, mean yr (range) | 13.5 (6–18) | 12.7 (6–17) | 30.8 (17–64) | 28.8 (18–53) | 30.5 (18–60) |

|

| |||||

| Male, n (%) | 41 (55.0) | 42 (51.9) | 68 (52.0) | 36 (54.5) | 38 (57.0) |

|

| |||||

| Caucasian, n (%) | 72 (97.3) | 79 (97.5) | 124 (93.9) | 62 (93.9) | 64 (95.5) |

|

| |||||

| CFTR Genotype, n (%) | |||||

| Homozygous ΔF508 | 42 (57.0) | 47(58.0) | 51 (39.0) | 26 (39.4) | 26 (39.0) |

| Heterozygous ΔF508 | 22 (30.0) | 19 (23.5) | 54 (41.0) | 28 (42.4) | 27 (40.0) |

| Other/Unknown | 10 (14.0) | 15 (18.5) | 27 (20.0) | 12 (18.2) | 14 (21.0) |

|

| |||||

| Sweat Chloride, mean mEq/L (SD) | 104 (19.5) | 103.9 (17.3) | 101.5 (19.7) | 103.6 (24.4) | 102.3 (20.9) |

|

| |||||

| Weight, mean kg (SD) | 45.0 (13.2) | 42.8 (13.6) | 62.4 (12.0) | 60.8 (11.6) | 63.7 (12.1) |

|

| |||||

| BMI, mean kg/m2 (SD) | 17.8 (2.5) | 18.1 (3.0) | 21.8 (3.3) | 21.4 (2.9) | 22.1 (3.0) |

|

| |||||

| FEV1 % predicted, mean (SD) | 73.1 (17.5) | 71.8 (18.6) | 56.3 (15.4) | 53.0 (15.4) | 58.1 (16.4) |

|

| |||||

| FVC % predicted, mean (SD) | 85.1 (13.7) | 87.5 (17.3) | 78.9 (14.6) | 74.8 (16.3) | 80.1 (18.1) |

|

| |||||

| P. aeruginosa positive, n (%) | 40 (54) | 41 (50.6) | 85 (64) | 42 (63.6) | 38 (57) |

|

| |||||

| S. aureus positive, n (%) | 36 (49) | 39 (48.1) | 43 (33) | 14 (21.2) | 19 (28) |

|

| |||||

| Global Ratings of Health Status | |||||

| Investigator | |||||

| Excellent | 11 (15) | 13 (16) | 21 (16) | 7 (10.6) | 10 (15) |

| Good | 51 (69) | 57 (70.4) | 89 (67) | 46 (69.7) | 48 (72) |

| Fair | 12 (16) | 11 (13.6) | 22 (17) | 13 (19.7) | 8 (12) |

| Poor/Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Patient | |||||

| Excellent | 13 (18) | 11 (13.6) | 11 (8) | 6 (9.1) | 8 (12) |

| Good | 53 (72) | 61 (75.3) | 92 (70) | 55 (83.3) | 51 (76) |

| Fair | 8 (11) | 9 (11.1) | 28 (21) | 5 (7.6) | 7 (10.5) |

| Poor/Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) |

Sweat Chloride, Genotype, and Microbiology Culture were ascertained at Screening Visit

Age, Weight, BMI, Spirometry, and Global Ratings of Health Status were ascertained at Baseline Visit

The trial was terminated early due to disproportionate incidence of respiratory serious adverse events (SAE) observed among adult subjects receiving BIIL 284 BS compared to those receiving placebo. These SAEs were characterized by increased presentation of respiratory signs and/or symptoms associated with pulmonary exacerbation and resulted in admission to a hospital and/or administration of IV antibiotics. At the time of the DMC analysis, 33 adults (29.7%) who had received either of the 2 doses of BIIL 284 BS had experienced an SAE versus only 12 (11.8%) of those receiving placebo (p = 0.001), and 12 adults (10.8%) receiving BIIL 284 BS had withdrawn from the study versus only 3 (2.9%) receiving placebo (p = 0.031). A similar (but not statistically significant) trend was observed in the pediatric population, with 12 pediatric subjects (19.7%) receiving BIIL 284 BS experiencing an SAE versus 7 (11.5%) that had received placebo (p = 0.318). Incidences of AE, SAE, and respiratory SAE in the final dataset were similar to those observed in the interim safety analysis (Table 2). In the pooled adult BIIL 284 BS arm, 48 of 133 (36.1%) experienced an SAE vs. 28 of 132 (21.2%) in the placebo arm (p = 0.007). In the pediatric BIIL 284 BS arm, 24 of 81 (29.6%) experienced at least one SAE vs. 22.9% (17/74) in the placebo arm (p = 0.348). The majority of all SAEs, 143/191 (74.9%), were coded as respiratory in nature.

Table 2.

Summary of Adverse Events*

| Pediatric Placebo (N=74) | Pediatric 75 mg (N=81) | Adult Placebo (N=132) | Adult 75 mg (N=66) | Adult 150 mg (N=67) | Adult Pooled (N=133) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| AEs | ||||||

| Total number | 296 | 322 | 676 | 330 | 344 | 674 |

| Subjects with ≥1, n (%) | 67 (90.5) | 72 (88.9) | 109 (82.6) | 61 (92.4) | 60 (89.6) | 121 (90.9) |

| Average number per subject | 4.42 | 4.47 | 6.20 | 5.41 | 5.73 | 5.57 |

| AE rate per wk of follow-up | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.38 |

|

| ||||||

| SAEs | ||||||

| Total number | 27 | 47 | 38 | 47 | 32 | 79 |

| Subjects with ≥1, n (%) | 17 (22.9) | 24 (29.6) | 28 (21.2) | 27 (40.9) | 21 (31.3) | 48 (36.1) |

| Average number per subject | 1.59 | 1.96 | 1.36 | 1.74 | 1.52 | 1.65 |

| SAE rate per wk of follow-up | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

|

| ||||||

| Respiratory SAEs | ||||||

| Total number | 22 | 35 | 30 | 33 | 23 | 56 |

| Subjects with ≥1, n (%) | 17 (22.9) | 22 (27.2) | 22 (16.7) | 24 (36.4) | 17 (25.4) | 41 (30.8) |

| Average number per subject | 1.29 | 1.59 | 1.36 | 1.38 | 1.35 | 1.37 |

| Rate per wk of follow-up | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

Treatment emergent AEs and SAEs: occur after the initiation of the first dose

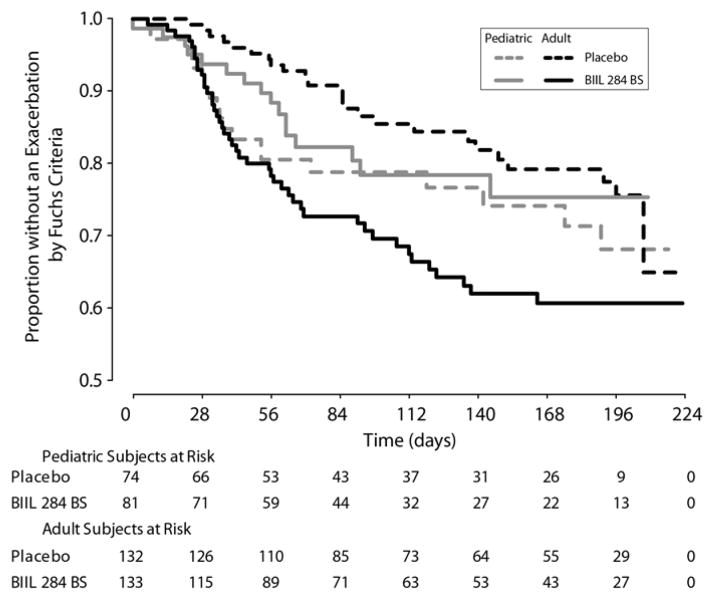

Treatment assignment for subjects with SAEs was confirmed by measuring plasma samples for BIIL 315 ZW. Plasma concentrations of subjects with SAEs were in the expected concentration range, and were similar to results obtained in earlier pharmacokinetic studies of BIIL 284 BS in adults and children with CF [19]. The median plasma concentrations in the time interval from 2 to 4 hours after drug administration for the 150 mg BIIL 284 BS adult early withdrawal group with SAEs and the 75 mg BIIL 284 BS pediatric early withdrawal group with SAEs, were 45.2 ng/mL (N=15) and 18.3 ng/mL (N=12) respectively. Prior to study termination, 103 (24.5%) treated subjects had experienced a protocol-defined pulmonary exacerbation. The incidence of exacerbation was significantly higher in adult subjects receiving BIIL 284 BS than those receiving placebo (33.12% versus 18.2%, p = 0.005). Similar numbers of pediatric subjects were treated for a pulmonary exacerbation in the BIIL 284 BS and placebo groups (16/81, 19.8%, and 19/74, 25.7%, respectively; p = 0.38). The Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig 2) for time to pulmonary exacerbation show statistically significant differences in curves between treatment groups in adults (p-value = 0.0023), but not across the treatment groups in pediatric subjects.

Figure 2.

Time to Protocol-defined Pulmonary Exacerbation

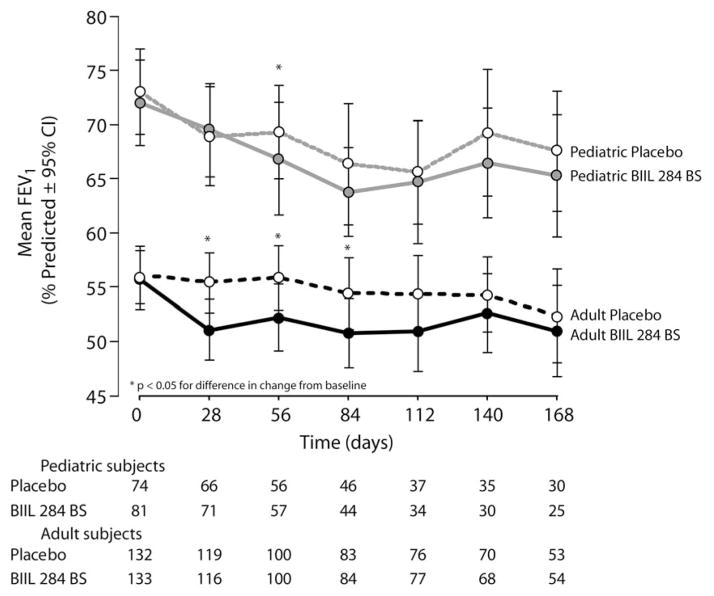

Early study termination prevented analyses of clinical efficacy endpoints as planned in the protocol. However, descriptive summary statistics of efficacy endpoints in which the data for were pooled for subjects in both adult dosing groups of BIIL 284 BS suggest a trend towards poorer average lung function (FEV1 % predicted) in subjects receiving BIIL 284 BS than in those receiving placebo (Fig. 3). Peripheral neutrophil (PMN) counts increased over the study period for adults receiving BIIL 284 BS, while they were reduced slightly for adults receiving placebo, with significant differences between groups observed at Days 28, 84, and 140, but not at Day 168 (Table 3). In contrast, average peripheral PMN count differences were significant for pediatric subjects only at Day 28. Data for peripheral lymphocyte and monocyte counts is included in the on-line supplement. Overall, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were not significantly changed over the study period, and there was no effect of treatment group on change from baseline for these measures.

Figure 3.

Change in Lung Function

Table 3.

Change from Baseline of Peripheral Neutrophil Count (PMN)

| Treatment group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Placebo | BIIL 75 mg | BIIL 150 mg | Difference (BIIL-Placebo)1 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Week | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | Mean (95% CI) | P-value | |

|

| |||||||||

| Pediatric | 74 | 80 | |||||||

| PMN (109/L) Change from Baseline2 | 4 | 66 | −0.3 (3.1) | 71 | 0.7 (2.8) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.049 | ||

| 12 | 45 | −0.5 (2.5) | 44 | 0.4 (2.8) | 0.9 (−0.2–2.0) | 0.124 | |||

| 20 | 35 | −0.1 (2.6) | 31 | −0.1 (2.8) | 0.0 (−1.4–1.3) | 0.975 | |||

| 24 | 28 | 0.2 (3.0) | 25 | 0.4 (2.6) | 0.2 (−1.3–1.8) | 0.762 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Adult | 131 | 65 | 64 | ||||||

| PMN (109/L) Change from Baseline3 | 4 | 116 | −0.7 (2.6) | 55 | 0.8 (3.0) | 57 | 0.8 (2.5) | 1.5 (0.8–2.2) | <.0001 |

| 12 | 81 | −0.2 (2.6) | 38 | 1.4 (2.9) | 43 | 0.1 (3.1) | 0.9 (0.0–1.8) | 0.045 | |

| 20 | 68 | −0.2 (3.0) | 31 | 2.0 (5.9) | 37 | 0.8 (2.9) | 1.6 (0.3–2.9) | 0.019 | |

| 24 | 52 | −0.4 (3.6) | 25 | 0.9 (2.6) | 28 | 0.3 (2.6) | 1.0 (−0.2–2.2) | 0.117 | |

for adults, calculated using pooled data from BIIL 75 mg and BIIL 150 mg

baseline: placebo = 6.1(3.2); BIIL 75 mg = 5.7 (2.6)

baseline: placebo = 6.9 (3.2); BIIL 75 mg = 5.9 (2.4); BIIL 150 mg = 6.0 (2.5)

DISCUSSION

Several clinical and experimental lines of evidence have suggested that LTB4 plays a key role in the pathophysiology of CF and other inflammatory diseases by promoting neutrophil adherence, aggregation, migration, degranulation, and superoxide release [27–33]. Thus, inhibition of LTB4 via antagonism of the LTB4 receptor was anticipated to provide some protective benefit to the CF lung with respect to inflammation and inflammatory damage. The early termination of this trial as a result of increased respiratory symptoms requiring IV antibiotics and hospitalization in adults receiving the LTB4-receptor antagonist BIIL 284 BS, combined with evidence of decreased pulmonary function and increased circulating PMN levels in subjects receiving BIIL 284 BS, suggests that antagonism of the LTB4 receptor may have resulted in an acute pulmonary exacerbation possibly associated with increased inflammation. Although significant safety concerns were evident only in adult subjects, the DMC included pediatric subjects in its recommendation for study termination because 1) the relative risk for drug-related SAE in the pediatric cohort was quantitatively similar to that observed in the adult cohorts; 2) there was a lower power to detect statistically significance differences in the pediatric cohort due to a lower level of recruitment, 3) there were no biological bases to assume that children should have a fundamentally different response to drug, 4) it was recognized that the study would be underpowered to detect benefit without participation of the adult cohorts, and 5) the early results of change in FEV1 did not appear to be supporting a beneficial effect of drug. The results from the final data presented here support and confirm the decision to terminate the trial.

The mechanism by which antagonism of the LTB4 receptor in subjects with CF might produce an increase in respiratory symptoms and concurrent decrease in pulmonary function is not clear. Many subjects in the study had chronic lung infection with pathogenic bacteria such as P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. It may be that a substantial reduction in PMN activity at the site of infection in the lung due to LTB4 receptor antagonism actually increased bacterial proliferation in the lung and possibly invasion into the parenchyma, which might explain why circulating counts of PMN were observed to be significantly elevated.

The therapeutic approach of reducing PMN-mediated inflammation in the CF lung by targeting LTB4 was suggested by a study using a rat model of chronic pseudomonas infection [34]. In that study, ibuprofen inhibited LTB4 release from neutrophils and reduced neutrophils in the lung without worsening pseudomonas infection. Long-term clinical trials and clinical practice suggest that the benefits of ibuprofen outweigh the risks in patients with CF [8–10]. It is possible that the doses of BIIL 284 BS chosen for this trial were higher than those necessary to effectively reduce PMN-based inflammation without allowing undesirable expansion of bacterial populations. The efficacy and safety of BIIL 284 BS has been evaluated in subjects with active rheumatoid arthritis in a 3-month multi-centre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [35,36]. A total of 342 subjects were randomized to receive 5 mg, 25 mg or 75 mg doses of BIIL 284 BS or placebo. The geometric mean concentration of BIIL 315 ZW for samples taken 1 to 4 hours post-dose was 19.4 mg/mL after treatment with 75 mg BIIL 284 BS, which is in the same range as the levels observed in the current study. In the rheumatoid arthritis study, BIIL 284 BS was determined to be safe and well tolerated. However, BIIL 284 BS produced only modest improvements in disease activity.

This trial of BIIL 284 BS in children and adults with CF highlights the value of incorporating an ongoing review of the safety data by an external, independent DMC into the study design. Also to be noted, the communication infrastructure available to the sponsor allowed for a rapid response following the DMC recommendation to terminate the study, both with regards to the decision-making process of the sponsor (i.e. decision to comply with the DMC recommendation) and the communication to the Investigators to discontinue all subjects from treatment.

The safety concern raised in this trial of a leukotriene receptor antagonist that targets a peptido-leukotriene (LTB4) cannot be extrapolated to leukotriene receptor antagonists that target cysteinyl leukotrienes (LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4). The former contributes to neutrophilic inflammation in the lung, while the latter, produced predominantly by eosinophils, mast cells, and macrophages, contribute to non-neutrophilic pulmonary inflammation [37]. The cysteinyl leuktriene receptor antagonist, montelukast, is frequently used to treat asthma, and has been used in patients with CF (particularly in those with bronchial hyperreactivity) with some evidence for benefit without apparent complications that would limit their use [37].

The outcome of this trial of BIIL 284 BS provides a cautionary tale for the administration of potent anti-inflammatory compounds to individuals with chronic infections, as the potential to significantly suppress the inflammatory response may increase the risk of infection-related adverse events. To mitigate risk in future trials of anti-inflammatory compounds in patients with CF, frequent monitoring for adverse events and perhaps including sputum biomarkers of infection and inflammation should be considered. The inclusion of a robust data safety monitoring committee with pre-defined safety and efficacy assessments, as was done in this trial, is paramount.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the patients, participating institutions, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Data Safety Monitoring Board and the Cystic Fibrosis Therapeutics Development Network for their contributions to the study.

Abbreviations

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- DMC

Data Monitoring Committee

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- IV

intravenous

- LTB4

leukotriene B4

- PMN

polymorphonuclear neutrophils

Footnotes

Supplementary data and a complete list of study site principal investigators and institutions can be found online at http://xxxxxxx.

DISCLOSURES

Funding for this study was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim. MK, GD, LL and KH have received consulting honoraria and/or travel expenses from Boehringer Ingelheim. PK, SB, AS, and AH are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. No writing assistance or compensation was provided to the authors in exchange for production of this manuscript. Boehringer Ingelheim was responsible for the study design, as well as the collection and analysis of the data. The decision to submit the manuscript was made by the authors and approved by Boehringer Ingelheim. All listed authors meet the criteria for authorship set forth by the International Committee for Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Cantin A. Cystic fibrosis lung inflammation: early, sustained, and severe. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:939–41. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.4.7697269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstan MW, Berger M. Current understanding of the inflammatory process in cystic fibrosis - onset and etiology. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1997;24:137–42. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199708)24:2<137::aid-ppul13>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Döring G, Ratjen F. Immunology of cystic fibrosis. In: Hodson ME, Geddes D, Bush A, editors. Cystic Fibrosis. London, England: Arnold Hammer; 2007. pp. 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Döring G, Conway SP, Heijerman HGM, et al. for the Consensus Committee. Antibiotic therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:749–767. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16d30.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Konstan MW. Therapies aimed at airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis. In: Fiel SB, editor. Clinics in Chest Medicine: Cystic Fibrosis. Vol. 19. Philadelphia: W.B, Saunders Co; 1998. pp. 505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Döring G, Hoiby N for the Consensus Study Group. Early intervention and prevention of lung disease in cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. J Cyst Fibros. 2004;3:67–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chmiel JF, Konstan MW. Inflammation and anti-inflammatory therapies for cystic fibrosis. Clin Chest Med. 2007;28(2):331–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konstan MW, Byard PJ, Hoppel CL, Davis PB. Effect of high-dose ibuprofen in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:848–854. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503303321303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lands LC, Milner R, Cantin AM, Manson D, Corey M. High-dose ibuprofen in cystic fibrosis: Canadian safety and effectiveness trial. J Pediatr. 2007;151:249–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konstan MW, Schluchter MD, Xue W, Davis PB. Clinical use of Ibuprofen is associated with slower FEV1 decline in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1084–1089. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-181OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konstan MW. Ibuprofen therapy for cystic fibrosis lung disease: revisited. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008 Nov;14(6):567–73. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32831311e8. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergmann U, Scheffer J, Koller M, Schonfeld W, Erbs G, Muller FE, Konig W. Induction of inflammatory mediators (histamine and leukotrienes) from rat peritoneal mast cells and human granulocytes by pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from burn patients. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2187–95. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.7.2187-2195.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford-Hutchinson AW, Bray MA, Doig MV, Shipley ME, Smith MJ. Leukotriene B, a potent chemokinetic and aggregating substance released from polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Nature. 1980;286:264–5. doi: 10.1038/286264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cromwell O, Walport MJ, Taylor GW, Morris HR, O’Driscoll BR, Kay AB. Identification of leukotrienes in the sputum of patients with cystic fibrosis. Adv Prostagland Thrombox Leukotriene Res. 1982;9:251–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konstan MW, Walenga RW, Hilliard KA, Hilliard JB. Leukotriene B4 is markedly elevated in epithelial lining fluid of patients with cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:896–901. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.4_Pt_1.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greally P, Hussein MJ, Cook AJ, Sampson AP, Piper PJ, Price JF. Sputum tumor necrosis factor-alpha and leukotriene concentrations in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:389–92. doi: 10.1136/adc.68.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence R, Sorrell T. Eicosapentaenoic acid in cystic fibrosis: evidence of a pathogenetic role for leukotriene B4. Lancet. 1993 Aug 21;342(8869):465–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91594-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birke FW, Meade CJ, Anderskewitz R, Speck GA, Jennewein H-M. In vitro and in vivo pharmacological characterization of BIIL 284, a novel and potent leukotriene B4 receptor antagonist. JPET. 2001;297(1):458–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konstan MW, Hilliard KA, Koker P, Hamilton AL, Staab A. Pharmacokinetics of BIIL 284 BS (Amelubant), an oral once-daily LTB4 receptor antagonist, in adult and pediatric CF patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;(Suppl 25):258–259. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konstan MW, Hilliard KA, Koker P, Hamilton AL, Staab A. Safety and tolerability of BIIL 284 BS (Amelubant), an oral once-daily LTB4 receptor antagonist, in adult and pediatric CF patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;(Suppl 25):259. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konstan MW, Döring G, Lands LC, Hilliard KA, Koker P, Bhattacharya S, Staab A, Hamilton AL. Results of a phase II clinical trial of BIIL 84 BS (an LTB4 antagonist) for the treatment of CF lung disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;(Suppl 28):125. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Thoracic Society. Standardization of spirometry – 1994 update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Dockery DW, et al. Pulmonary function between 6 and 18 years of age. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1993;15:75–88. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950150204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knudson RJ, Lebowitz MD, Holberg CJ, Burrows B. Changes in the normal maximal expiratory flow-volume curve with growth and aging. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:725–734. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.6.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuchs HJ, Borowitz DS, Christiansen DH, Morris EM, et al. Effect of aerosolized recombinant human DNase on exacerbations of respiratory symptoms and on pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:637–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409083311003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lymp J, Hilliard K, Rosenfeld M, Koker P, Hamilton A, Konstan M. Pulmonary exacerbations in a phase 2 clinical trial of BIIL284BS in CF: development and implementation of a respiratory and systemic symptoms questionnaire (RSSQ) Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;(Suppl 32):288. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spencer DA, Sampson AP, Green CP, Costello JF, Piper PJ, Price JF. Sputum cysteinyl-leukotriene levels correlate with severity of pulmonary disease in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1992;12:90–94. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950120206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zakrzewski JT, Barnes NC, Piper PJ, Costello JF. Detection of sputum eicosanoids in cystic fibrosis and in normal saliva by bioassay and radioimmunoassay. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;23:19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Csoma Z, Kharitonov SA, Balint B, Bush A, Wilson NM, Barnes PJ. Increased leukotrienes in exhaled breath condensate in childhood asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1345–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-233OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wardlaw AJ, Hay H, Cromwell O, Collins JV, Kay AB. Leukotrienes, LTC4 and LTB4, in bronchoalveolar lavage in bronchial asthma and other respiratory diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;84:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole AT, Pilkington BJ, McLaughlan J, Smith C, Balsitis M, Hawkey CJ. Mucosal factors inducing neutrophil movement in ulcerative colitis: The role of interleukin 8 and leukotriene B4. Gut. 1996;39:248–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmadzadeh N, Shingu M, Nobunaga M, Tawara T. Relationship between leukotriene B4 and immunological parameters in rheumatoid synovial fluids. Inflammation. 1991;15:497–503. doi: 10.1007/BF00923346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffiths RJ, Pettipher ER, Koch K, et al. Leukotriene B4 plays a critical role in the progression of collagen-induced arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:517–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konstan MW, Vargo KM, Davis PB. Ibuprofen attenuates the inflammatory response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a rat model of chronic pulmonary infection. Implications for antiinflammatory therapy in cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990 Jan;141(1):186–92. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alten R, Gromnica-Ihle E, Pohl C, et al. Inhibition of leukotriene B4-induced CD11B/CD18 (Mac-1) expression by BIIL 284, a new long acting LTB4 receptor antagonist, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:170–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2002.004499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Díaz-González F, Alten RHE, William G, Bensen WB, et al. Clinical trial of a leukotriene B4 receptor antagonist, BIIL 284, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:628–32. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitt-Grohé S, Zielen S. Leukotriene receptor antagonists in children with Cystic Fibrosis lung disease: anti-inflammatory and clinical effects. Pediatr Drugs. 2005;7(6):353–63. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200507060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.