Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Is dairy food consumption associated with live birth among women undergoing infertility treatment?

SUMMARY ANSWER

There was a positive association between total dairy food consumption and live birth among women ≥35 years of age.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

Dairy food intake has been previously related to infertility risk and measures of fertility potential but its relation to infertility treatment outcomes are unknown.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

Our study population comprised a total of 232 women undergoing 353 in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment cycles between February 2007 and May 2013, from the Environment and Reproductive Health study, an ongoing prospective cohort.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Diet was assessed before assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment using a validated food frequency questionnaire. Study outcomes included ovarian stimulation outcomes (endometrial thickness, estradiol levels and oocyte yield), fertilization rates, embryo quality measures and clinical outcomes (implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth rates). We used generalized linear mixed models with random intercepts to account for multiple ART cycles per woman while simultaneously adjusting for age, caloric intake, BMI, race, smoking status, infertility diagnosis, protocol type, alcohol intake and dietary patterns.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

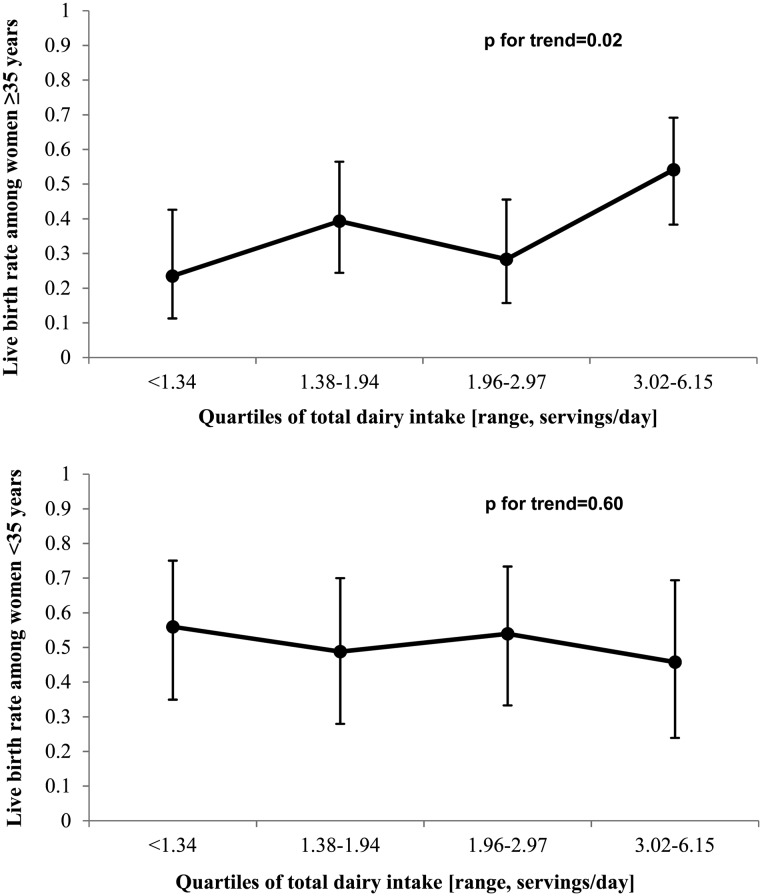

The age- and calorie-adjusted difference in live birth between women in the highest (>3.0 servings/day) and lowest (<1.34 servings/day) quartile of dairy intake was 21% (P = 0.02). However, after adjusting for additional covariates, this association was observed only among women ≥35 years (P, interaction = 0.04). The multivariable-adjusted live birth (95% CI) in increasing quartiles of total dairy intake was 23% (11, 42%), 39% (24, 56%), 29% (17, 47%) and 55% (39, 69%) (P, trend = 0.02) among women ≥35 years old, and ranged from 46 to 54% among women <35 years old (P, trend = 0.69). There was no association between dairy intake and any of the intermediate outcomes.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

The lack of a known biological mechanism linking dairy intake to infertility treatment outcomes calls for caution when interpreting these results and for additional work to corroborate or refute them.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Dairy intake does not appear to harm IVF outcomes and, if anything, is associated with higher chances of live birth.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTERESTS

This work was supported by NIH grants R01-ES009718 and R01ES000002 from NIEHS, P30 DK046200 from NIDDK and T32HD060454 from NICHD. M.C.A. was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 DK 007703-16 from NIDDK. She is currently employed at the Nestlé Research Center, Switzerland and completed this work while at the Harvard School of Public Health. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Keywords: diet, dairy, in vitro fertilization outcomes, assisted reproductive technology, live birth rate

Introduction

One in six couples experiences infertility at some point in their reproductive life (Hoffman and Williams, 2012). While women's age and BMI are the best characterized risk factors for infertility, emerging literature suggests that diet may also impact a couple's ability to get pregnant independent of a woman's weight (Vujkovic et al., 2010; Gaskins et al., 2014; Mumford et al., 2014). Dairy foods contribute 9% of calories to the average American diet (U.S. Department of Agriculture et al., 2011) and their share continues to increase (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2003). Previous work suggests that this trend may be of concern. In rodent studies, high amounts of galactose intake, which in humans is solely derived from dairy foods, cause reduced ovulatory rates and premature ovarian failure (POF) (Swarts and Mattison, 1988; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2003). Moreover, in the USA and other in Western countries, milk and dairy products contain measurable amounts of reproductive hormones (García-Peláez et al., 2004; Pape-Zambito et al., 2010) as cows are milked up to the third trimester of pregnancy (Daxenberger et al., 2001).

Nevertheless, human studies investigating the association of dairy products and female fertility have yielded inconsistent results (Cramer et al., 1994; Greenlee et al., 2003; Chavarro et al., 2007; Toledo et al., 2011). While milk consumption was associated with age-related decreases in fertility rates in a 31-countries ecologic study (Cramer et al., 1994), a subsequent case–control study found that women who consumed three or more glasses of milk per day had a 70% lower risk of infertility when compared with women who did not consume milk (Greenlee et al., 2003). Moreover, a prospective cohort study found that intake of high-fat dairy foods was associated with a lower risk of ovulatory infertility, while intake of low-fat dairy foods was associated with a higher risk of ovulatory infertility (Chavarro et al., 2007). Of note, no study has so far examined whether dairy food intake is related to outcomes of women undergoing assisted reproduction. Thus, in this study, we evaluated dairy food intake in relation to live birth per initiated cycle among women undergoing infertility treatment at an academic medical center in Boston, MA, USA. In addition, we made use of intermediate outcomes to gain insights into the potential biological mediators of this relation. We hypothesized that intake of total and full-fat dairy foods would be associated with lower chances of live birth.

Materials and Methods

Study population

Subfertile couples attending the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) fertility center were invited to enroll in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) study, an ongoing prospective cohort started in 2006 to identify environmental and nutritional determinants of fertility among couples (Hauser et al., 2006). A food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was introduced in 2007. At enrollment, trained research nurses administered a general health questionnaire (about demographics, lifestyle and medical history) and carried out an anthropometric assessment. Our initial study population consisted of the 316 women who completed at least one in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment cycle between February 2007 and May 2013. We excluded 76 women who were missing diet information and 8 women for whom diet was assessed more than 3 months after treatment had already started, resulting in 232 women with 353 cycles in our analytic dataset. Characteristics of women included and excluded from the analysis were similar except that excluded women had a higher percentage of cycles that failed before embryo transfer and diminished ovarian reserve and endometriosis. The women were then followed during each of their treatment cycles until either a live birth was achieved or they discontinued their treatment at MGH. The sample size for each outcome depends on the success of the previous stage. Out of 353 initiated cycles (including 30 cryopreserved cycles and 18 donor oocyte cycles), there were 305 fresh IVF cycles. Of these fresh cycles, oocytes were retrieved from 288 cycles while 17 fresh cycles were canceled or converted to intrauterine insemination cycles (IUI). A total of 322 cycles had an embryo transfer: 277 fresh cycles with successful fertilization and embryo development, 28 cryopreservation cycles and 17 donor oocyte cycles. After embryo transfer, there were 207 implantations, 185 clinical pregnancies and 149 cycles with live birth.

Ethical approval

All women signed an informed consent document. The study was approved by the Human Subject Committees of the Harvard School of Public Health and MGH.

Clinical management and assessment of outcomes

Our primary outcome of interest was live birth per initiated cycle. However, we made use of intermediate outcomes to gain insights into the potential biological mediators of the dairy intakes and live birth relation.

After completing a cycle of oral contraceptives, women underwent one of three controlled ovarian stimulation IVF treatment protocols on Day 3 of induced menses: (i) luteal phase GnRH-agonist protocol, (ii) follicular phase GnRH-agonist/Flare protocol or (iii) GnRH-antagonist protocol. In the luteal phase GnRH-agonist protocol, the Lupron dose was reduced at, or shortly after, the start of ovarian stimulation with FSH/hMG. FSH/hMG and GnRH-agonist or GnRH-antagonist was continued to the day of trigger with Human Chorionic Gonadotrophin (hCG), 36 h before oocyte retrieval. Estradiol levels were measured throughout the monitoring phase of the subject's IVF treatment cycle (Elecsys Estradiol II reagent kit, Roche Diagnostics). Oocyte retrieval was performed when follicle sizes on transvaginal ultrasound reached 16–18 mm and the estradiol level reached at least 500 pg/ml. Endometrial thickness was also monitored by ultrasound during this phase and the thickness reached on the day of hCG trigger injection was recorded.

Trained embryologists identified the total number of oocytes retrieved per cycle and classified them as germinal vesicle, metaphase I, metaphase II (MII) or degenerated. Oocytes underwent either IVF or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) as clinically indicated. Oocytes were checked for fertilization 17–20 h after insemination and those fertilized were graded as either normally fertilized (two pronuclei) or abnormally fertilized (one or poly pronuclear). The resulting embryos were assessed for quality according to their morphological characteristics on Day 3 and assigned a score between 1 (best) and 5 (worst), with grades 3, 4 and 5 considered poor quality. Embryo cleavage rate was assessed by counting the number of cells in the embryo on Day 3. Embryos that had reached 6–8 cells were considered to be cleaving at a normal rate, embryos with 5 cells or fewer were considered to be slow cleaving, and embryos with 9 or more cells were considered to have accelerated cleavage. For this analysis, embryos were classified as best quality if they had 4 cells on Day 2, 8 cells on Day 3, and a morphologic quality score of 1 or 2 on Days 2 and 3. The number of embryos transferred was determined using the American Society for Reproductive Medicine's embryo transfer guidelines (Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine and Practice Committee of Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, 2013) and that was not in any way influenced by study participation.

Clinical outcomes were assessed among women who underwent an embryo transfer. Successful implantation was defined as an elevation in plasma β-hCG levels above 6 IU/l after embryo transfer. Clinical pregnancy was defined as an elevation in β-hCG with the confirmation of an intrauterine pregnancy by ultrasound, first performed at 6 weeks of gestation. Live birth was defined as the birth of a neonate on or after 24 weeks gestation. All clinical outcomes were abstracted from the patients' medical records.

Dietary assessment

Participants completed a previously validated 131-item FFQ (Rimm et al., 1992). They were asked to report how often, on average, they consumed specific amounts of each foods, beverages and supplements, during the previous year. Participants were asked to indicate the multivitamin and supplement brands, dose and frequency of use. The FFQ had nine categories for food intake frequency options that ranged from never to six or more times per day. There were 15 questions in the FFQ that addressed dairy intake. The nutrient content of each food, its specific portion size and supplements was calculated by the nutrient database from the US Department of Agriculture (U.S. Department of Agriculture ARS, 2012) with additional information from manufacturers when necessary. Assessment of dairy food intake using this questionnaire has been validated against prospectively collected diet records in a separate population (Salvini et al., 1989). The de-attenuated correlation between specific dairy foods assessed with the FFQ and the 1 year average of prospectively collected diet records ranged from 0.57 for hard cheese to 0.94 for yogurt (Salvini et al., 1989). For our analysis, cheese was defined as the sum of cream cheese and other cheeses. Low-fat milk was defined as the sum of skim milk and reduced fat (1 and 2%) milk. Full-fat dairy intake was defined as the sum of whole milk, cream, ice cream and cheese. Low-fat dairy was defined as the sum of low-fat milk, yogurt and cottage cheese. Total dairy food intake was defined as the sum of full-fat and low-fat dairy. Non-dairy protein intake was calculated as the difference between protein intake and dairy protein intake. Similarly, we calculated non-dairy fat and non-dairy carbohydrate intake. We used two data-derived dietary patterns to describe general patterns of food consumption (Gaskins et al., 2012): the ‘prudent pattern’, characterized by intakes of fish, fruits, cruciferous vegetables, yellow vegetables, tomatoes, leafy green vegetables and legumes; while the Western pattern was characterized by high intakes of processed meat, full-fat dairy, fries, refined grains, pizza and mayonnaise. Women received a score on each of these patterns ranging from −2.9 to 4.7 with higher scores indicating higher adherence to each of these dietary patterns.

Statistical analysis

We first summarized participant characteristics and compared them across quartiles of total dairy food intake. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare differences in continuous measures across categories of dairy intake and χ2 tests and an extended Fisher's Exact test (when one or more cell counts were ≤5) for categorical variables. We used multivariate generalized linear mixed models with random intercepts to account for multiple ART cycles per woman. A Poisson distribution and log link function were stipulated for oocyte counts and a binomial distribution and logit link function were stipulated for fertilization, embryo quality and clinical outcomes. Peak estradiol was evaluated with a normal distribution and identity link function. Tests for linear trends (Rosner, 2000) were conducted using the median values of each quartile of dairy intake as a continuous variable. Data are presented as population marginal means, adjusted for covariates (Searle et al., 1980). Specific dairy foods were first considered as quintiles and when the distribution was too narrow, we categorized them as quartiles or tertiles.

Confounding was assessed using prior knowledge regarding biological relevance as well as descriptive statistics from our study population. Covariates considered in full models included: calorie intake (continuous), age (continuous), BMI (continuous), race (white versus other), smoking status (ever smoker versus other), infertility diagnosis (male factor, female factor or unexplained infertility), treatment protocol type (Luteal phase agonist, Flare or GnRH-antagonist), alcohol intake (continuous) and dietary patterns (continuous). The full-fat dairy models were additionally adjusted for low-fat dairy and vice versa. We further examined whether dairy macronutrients were associated with outcomes using the nutrient density method (Willett, 2013) where energy bearing nutrients are expressed as the percentage of total calories. Covariates were similar to the ones mentioned above with three exceptions: models were not adjusted for dietary patterns but instead for the non-dairy portion of that macronutrient and adding a term for total fat, protein or carbohydrate intake.

To account for the potential for exposure misclassification as time between diet assessment and outcome assessment increased, we conducted a sensitivity analysis restricting to each women's first ART cycle (n = 232 women, 232 cycles). We also assessed effect modification of dietary associations with outcomes by BMI (<25 versus ≥25 kg/m2), smoking status (never versus ever smokers), age (<35 versus ≥35 years) and infertility diagnosis type (male, female and unexplained) using cross-product terms in the final multivariable model. These analyses were adjusted for the same covariates as in the main analysis (mentioned above). SAS (Versions 9.3 and 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Our study population consisted of 232 women who collectively underwent 353 ART cycles. The women's mean age (SD) was 35.2 (4.5) years; the majority was white (81%) and had never smoked (72%). The women's mean BMI was 24.2 (4.2) kg/m2, and 9% were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2). The majority of women (79%) reported undergoing a previous infertility exam; 46% had a previous IUI cycle and 25% a previous IVF cycle. Cheese was the most commonly consumed dairy food (32%), followed by low-fat milk (29%) and yogurt (19%). Total dairy intake was positively related to total energy intake, dairy fat and protein intakes, and the Western food pattern score and negatively related to alcohol intake (Table I).

Table I.

Demographic and dietary characteristics of 232 women in the EARTH Study by quartile of total dairy intake.

| Total dairy intake |

Pa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (lowest) | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 (highest) | ||

| n | 58 | 58 | 58 | 58 | |

| Range, servings/day | <1.34 | 1.38–1.94 | 1.96–2.97 | 3.02–6.15 | |

| Median (IQR) or n women (%) | |||||

| Personal characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 34.0 (32.0, 37.0) | 35.0 (33.0, 38.0) | 35.0 (32.0, 39.0) | 36.0 (33.0, 40.0) | 0.09 |

| White/Caucasian, n (%) | 45 (77.6) | 44 (75.9) | 49 (84.5) | 49 (84.5) | 0.51 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.8 (21.1, 25.6) | 24.0 (21.0, 26.8) | 22.9 (21.2, 25.0) | 23.4 (21.6, 27.7) | 0.52 |

| Ever smoker, n (%) | 19 (32.8) | 10 (17.2) | 18 (31.0) | 19 (32.8) | 0.18 |

| Baseline reproductive characteristics | |||||

| Initial infertility diagnosis (%) | 0.20 | ||||

| Male factor | 14 (24.1) | 25 (43.1) | 19 (32.8) | 24 (41.4) | |

| Female factor | |||||

| Endometriosis | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (6.9) | 3 (5.2) | |

| Tubal factor | 7 (12.1) | 3 (5.2) | 2 (3.5) | 5 (8.6) | |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 3 (5.2) | 4 (6.9) | 3 (5.2) | 7 (12.1) | |

| Ovulation disorders | 4 (6.9) | 6 (10.3) | 8 (13.8) | 2 (3.5) | |

| Uterine disorders | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Unexplained | 28 (48.3) | 19 (32.8) | 21 (36.2) | 17 (29.3) | |

| Initial treatment protocol (%) | 0.73 | ||||

| Antagonist | 5 (8.6) | 7 (12.1) | 4 (6.9) | 7 (12.1) | |

| Flareb | 8 (13.8) | 5 (8.6) | 5 (8.6) | 9 (15.5) | |

| Luteal phase agonistc | 45 (77.6) | 46 (79.3) | 49 (84.5) | 42 (72.4) | |

| Day 3 FSH, IU/ld | 6.5 (5.4, 7.9) | 6.9 (5.9, 8.5) | 6.8 (5.7, 8.2) | 6.9 (5.8, 8.1) | 0.75 |

| Previous infertility exam, n (%) | 44 (75.9) | 46 (80.7) | 48 (82.8) | 44 (75.9) | 0.73 |

| Previous IUI, n (%) | 24 (41.4) | 27 (45.6) | 28 (48.3) | 27 (46.6) | 0.89 |

| Previous IVF, n (%) | 10 (17.2) | 17 (29.3) | 19 (32.8) | 13 (22.4) | 0.22 |

| Embryo transfer day, n women (%) | 0.28 | ||||

| No embryos transferred | 7 (12.1) | 4 (6.9) | 6 (10.3) | 4 (6.9) | |

| Day 2 | 6 (10.3) | 2 (3.5) | 2 (3.5) | 2 (3.5) | |

| Day 3 | 21 (36.2) | 27 (46.6) | 29 (50.0) | 33 (56.9) | |

| Day 5 | 22 (37.9) | 17 (29.3) | 18 (31.0) | 15 (25.9) | |

| Oocyte donor or cryo cycle | 2 (3.5) | 8 (13.8) | 3 (5.2) | 4 (6.9) | |

| Number of embryos transferred, n women (%) | 0.08 | ||||

| No embryos transferred | 7 (12.1) | 4 (6.9) | 6 (10.3) | 4 (6.9) | |

| 1 embryo | 4 (6.9) | 6 (10.3) | 9 (15.5) | 6 (10.3) | |

| 2 embryos | 41 (70.7) | 32 (55.2) | 32 (55.2) | 28 (48.3) | |

| 3+ embryos | 4 (6.9) | 8 (13.8) | 8 (13.8) | 16 (27.6) | |

| Oocyte donor or cryo cycle | 2 (3.5) | 8 (13.8) | 3 (5.2) | 4 (6.9) | |

| Dietary characteristics | |||||

| Total energy intake (kcal/day) | 1397 (1104, 1733) | 1571 (1369, 1973) | 1856 (1505, 2276) | 1989 (1724, 2469) | <0.0001 |

| Caffeine intake (mg/day) | 106.7 (26.8, 216.2) | 125.3 (57.0, 201.7) | 93.9 (51.6, 175.7) | 94.4 (30, 225.4) | 0.52 |

| Alcohol intake (g/day) | 13.0 (2.3, 23.0) | 7.2 (2.3, 20.9) | 6.9 (1.3, 12.9) | 5.3 (1.4, 12.5) | 0.05 |

| Fat intake (% energy) | 31.5 (28.6, 36.6) | 32.4 (27.4, 36.2) | 33.3 (28.1, 36.2) | 32.5 (28.8, 35.2) | 0.98 |

| Dairy fat intake (% energy) | 4.1 (2.7, 6.7) | 6.9 (4.6, 8.7) | 7.8 (5.6, 10.3) | 9.4 (7.1, 12.1) | <0.0001 |

| Protein intake (% energy) | 16.4 (14.4, 18.0) | 16.1 (14.6, 18.2) | 16.3 (14.4, 17.9) | 16.9 (15.7, 18.1) | 0.18 |

| Dairy protein intake (% energy) | 2.4 (1.6, 3.4) | 3.8 (2.8, 4.4) | 4.2 (3.3, 5) | 5.2 (4.2, 6.4) | <0.0001 |

| Carbohydrate intake (% energy) | 49.8 (45.7, 54.5) | 48.3 (43.5, 56.5) | 50.3 (46.5, 53.5) | 49.9 (44.2, 54.8) | 0.95 |

| Lactose intake (% energy) | 1.9 (1.1, 3.3) | 3.6 (2.3, 4.7) | 3.8 (2.6, 4.7) | 3.9 (2.8, 6.9) | <0.0001 |

| Prudent pattern score | −0.3 (−0.9, 0.4) | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.3) | −0.1 (−0.8, 0.4) | 0 (−0.5, 0.5) | 0.39 |

| Western pattern score | −0.6 (−1.1, 0.1) | −0.2 (−0.9, 0.2) | 0.1 (−0.5, 0.7) | 0.4 (−0.2, 0.9) | <0.0001 |

| Total folate (µg/day) | 975 (773, 1386) | 1197 (811, 1460) | 1158 (835, 1391) | 1224 (832, 1450) | 0.61 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg/day) | 11.9 (7.7, 16.9) | 11.9 (9.9, 16.5) | 11.5 (9.6, 16.2) | 13.7 (10.8, 17.1) | 0.39 |

| Calcium (mg/day) | 1008 (830, 1430) | 1190 (1031, 1545) | 1238 (1040, 1516) | 1358 (1162, 1625) | 0.001 |

| Dairy calcium (mg/day) | 361 (249, 528) | 588 (426, 729) | 662 (484, 796) | 813 (535, 986) | <0.0001 |

| Calcium from supplements (mg/day) | 401 (222, 435) | 398 (233, 417) | 399 (232, 407) | 400 (294, 413) | 0.63 |

| Total vitamin D (IU/day) | 570 (431, 746) | 585 (506, 723) | 557 (432, 677) | 600 (491, 707) | 0.51 |

| Dairy vitamin D (IU/day) | 35 (24, 100) | 101 (53, 168) | 92 (56, 132) | 110 (59, 173) | <0.0001 |

| Vitamin D from supplements (IU/day) | 169 (7, 516) | 201 (46, 438) | 180 (37, 466) | 194 (31, 209) | 0.87 |

| Multivitamin use, n (%)e | 51 (89.5) | 50 (89.3) | 52 (89.7) | 51 (87.9) | 0.99 |

IUI, intrauterine insemination; IVF, in vitro fertilization; IQR, interquartile range.

aFrom Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and χ2 tests and fisher exact tests (when one or more cell counts were ≤5) for categorical variables.

bFollicular phase GnRH-agonist/Flare protocol.

cLuteal phase GnRH-agonist protocol.

dSample size by quartiles of total dairy intake n = 48, 44, 50 and 52.

eA total of three women did not report whether or not they were consuming multivitamins. Sample size by quartiles of total dairy intake n = 57, 56, 58 and 58.

Total dairy intake was positively associated with live birth in analyses adjusted for age and total energy intake (Table II). The age- and calorie-adjusted difference in live birth between women in the lowest and women in the highest quartile of dairy intake was 21% (P-value = 0.02). This association was attenuated and became no longer significant after adjustment for other potential confounders including BMI, race, smoking status, infertility diagnosis, stimulaiton protocol, alcohol intake and dietary patterns. In these models, the adjusted difference in live birth between women in the lowest and women in the highest quartile of dairy intake was 16% (P-value = 0.10). No significant association of live birth with intakes of full-fat and low-fat dairy was observed. When individual dairy foods were examined in relation to clinical outcomes, no associations between specific dairy foods and these outcomes was observed (Table III), and dairy protein, dairy fat, lactose, dairy vitamin D and dairy calcium were also not associated with clinical outcomes (data not shown). When we evaluated intermediate end-points of ART, total dairy intake was unrelated to ovarian stimulation outcomes (Supplementary data, Table SI), fertilization (Supplementary data, Table SII), or embryo quality (Supplementary data, Table SIII).

Table II.

Association between dairy intake and clinical outcomes per initiated cycle in 232 women (353 cycles) from the EARTH Study.a

| Successful implantation |

Clinical pregnancy |

Live birth |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile (range, servings/day) | Adjusted mean (95% CI) |

Adjusted mean (95% CI) |

Adjusted mean (95% CI) |

|||

| Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 1b | Model 2c | |

| Total dairy | ||||||

| <1.34 | 0.52 (0.40, 0.63) | 0.58 (0.46, 0.70) | 0.48 (0.36, 0.60) | 0.54 (0.41, 0.66) | 0.34 (0.24, 0.46) | 0.38 (0.26, 0.52) |

| 1.38–1.94 | 0.64 (0.53, 0.74) | 0.65 (0.53, 0.75) | 0.55 (0.44, 0.66) | 0.56 (0.44, 0.67) | 0.42 (0.31, 0.54) | 0.42 (0.30, 0.54) |

| 1.96–2.97 | 0.52 (0.41, 0.63) | 0.48 (0.37, 0.60) | 0.50 (0.39, 0.62) | 0.46 (0.34, 0.58) | 0.44 (0.32, 0.56) | 0.39 (0.27, 0.52) |

| 3.02–6.15 | 0.67 (0.57, 0.77) | 0.66 (0.54, 0.76) | 0.60 (0.49, 0.71) | 0.59 (0.47, 0.70) | 0.55 (0.43, 0.66)* | 0.54 (0.41, 0.66) |

| P-trendd | 0.12 | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| Full-fat dairye | ||||||

| <0.59 | 0.46 (0.35, 0.58) | 0.49 (0.36, 0.62) | 0.44 (0.33, 0.57) | 0.46 (0.33, 0.59) | 0.34 (0.23, 0.47) | 0.36 (0.24, 0.50) |

| 0.61–0.98 | 0.65 (0.54, 0.75)* | 0.65 (0.54, 0.75) | 0.60 (0.49, 0.70) | 0.61 (0.49, 0.72) | 0.44 (0.33, 0.56) | 0.44 (0.33, 0.57) |

| 1.00–1.59 | 0.65 (0.53, 0.75)* | 0.63 (0.51, 0.74) | 0.55 (0.44, 0.67) | 0.53 (0.41, 0.65) | 0.45 (0.33, 0.57) | 0.42 (0.30, 0.55) |

| 1.61–4.24 | 0.61 (0.50, 0.71) | 0.61 (0.48, 0.72) | 0.55 (0.44, 0.66) | 0.55 (0.42, 0.67) | 0.51 (0.40, 0.63) | 0.51 (0.38, 0.63) |

| P-trend | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.08 | 0.18 |

| Low-fat dairyf | ||||||

| <0.47 | 0.58 (0.46, 0.68) | 0.61 (0.50, 0.72) | 0.52 (0.41, 0.64) | 0.56 (0.44, 0.68) | 0.40 (0.29, 0.52) | 0.43 (0.31, 0.55) |

| 0.48–0.89 | 0.58 (0.45, 0.69) | 0.58 (0.45, 0.70) | 0.50 (0.38, 0.63) | 0.49 (0.36, 0.62) | 0.39 (0.27, 0.52) | 0.37 (0.25, 0.51) |

| 0.90–1.18 | 0.55 (0.44, 0.65) | 0.54 (0.43, 0.64) | 0.48 (0.38, 0.59) | 0.47 (0.36, 0.59) | 0.42 (0.31, 0.53) | 0.42 (0.31, 0.53) |

| 1.20–5.30 | 0.67 (0.56, 0.77) | 0.66 (0.54, 0.76) | 0.64 (0.52, 0.74) | 0.62 (0.49, 0.73) | 0.53 (0.41, 0.65) | 0.51 (0.38, 0.63) |

| P-trend | 0.33 | 0.74 | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.14 | 0.39 |

aAll analyses were conducted using generalized linear mixed models with random intercepts, binomial distribution, logit link function and compound symmetry correlation structure.

bData are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI) for the proportion with the indicated outcome, adjusted for total calorie intake and age.

cData are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI) for the proportion with the indicated outcome, adjusted for total calorie intake, age, BMI, race, smoking status, infertility diagnosis, protocol type, alcohol intake and dietary patterns.

dTest for trend were performed using the median level of dairy in each quartile as a continuous variable in the model.

eAdjusted for footnote ‘b’ and low-fat dairy.

fAdjusted for footnote ‘b’ and full-fat dairy.

Full-fat dairy includes whole milk, cream, ice cream and cheese; low-fat dairy includes reduced fat milk, yogurt and cottage cheese.

*Indicates a P < 0.05 comparing that quartile versus first quartile.

Table III.

Association between specific dairy foods and estimated proportion with clinical outcomes in 232 women (353 cycles) from the EARTH Study.a

| N women | Successful implantation | Clinical pregnancy | Live birth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted mean proportion (95% CI)b |

||||

| Cheesec | ||||

| <0.22 | 58 | 0.58 (0.45, 0.70) | 0.54 (0.41, 0.67) | 0.41 (0.29, 0.55) |

| 0.28–0.45 | 47 | 0.54 (0.42, 0.66) | 0.48 (0.35, 0.60) | 0.37 (0.26, 0.50) |

| 0.51–0.94 | 70 | 0.60 (0.49, 0.71) | 0.57 (0.46, 0.68) | 0.48 (0.37, 0.60) |

| 1.00–3.00 | 57 | 0.65 (0.53, 0.76) | 0.55 (0.42, 0.67) | 0.45 (0.32, 0.58) |

| P-trendd | 0.32 | 0.63 | 0.46 | |

| Cream | ||||

| <0.02 | 99 | 0.59 (0.50, 0.67) | 0.53 (0.44, 0.62) | 0.42 (0.33, 0.51) |

| 0.08–0.14 | 57 | 0.67 (0.56, 0.77) | 0.61 (0.49, 0.72) | 0.47 (0.35, 0.59) |

| 0.43–2.00 | 76 | 0.55 (0.45, 0.65) | 0.50 (0.39, 0.60) | 0.43 (0.33, 0.54) |

| P-trend | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.98 | |

| Whole milk | ||||

| None | 144 | 0.63 (0.56, 0.70) | 0.57 (0.49, 0.64) | 0.48 (0.41, 0.56) |

| 0.02 | 41 | 0.49 (0.35, 0.62) | 0.42 (0.29, 0.56) | 0.32 (0.20, 0.46) |

| 0.08–1.00 | 47 | 0.58 (0.45, 0.69) | 0.54 (0.42, 0.66) | 0.37 (0.26, 0.51) |

| P-value | 0.59 | 0.90 | 0.22 | |

| Ice cream | ||||

| <0.02 | 109 | 0.53 (0.45, 0.61) | 0.49 (0.41, 0.58) | 0.42 (0.34, 0.51) |

| 0.08 | 79 | 0.69 (0.59, 0.77)* | 0.60 (0.50, 0.70) | 0.48 (0.38, 0.59) |

| 0.14–1.00 | 44 | 0.59 (0.46, 0.71) | 0.52 (0.39, 0.65) | 0.38 (0.26, 0.52) |

| P-trend | 0.19 | 0.46 | 0.81 | |

| Low-fat milke | ||||

| <0.08 | 66 | 0.62 (0.51, 0.73) | 0.57 (0.46, 0.68) | 0.45 (0.33, 0.57) |

| 0.10–0.28 | 41 | 0.55 (0.41, 0.68) | 0.50 (0.36, 0.63) | 0.39 (0.26, 0.54) |

| 0.43–0.80 | 72 | 0.54 (0.43, 0.64) | 0.47 (0.36, 0.57) | 0.41 (0.31, 0.52) |

| 0.82–4.00 | 53 | 0.68 (0.56, 0.78) | 0.62 (0.5, 0.73) | 0.47 (0.35, 0.60) |

| P-trend | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.58 | |

| Yogurtf | ||||

| <0.08 | 53 | 0.55 (0.43, 0.66) | 0.47 (0.35, 0.59) | 0.34 (0.23, 0.47) |

| 0.10–0.28 | 63 | 0.64 (0.53, 0.74) | 0.57 (0.46, 0.68) | 0.44 (0.33, 0.56) |

| 0.30–0.57 | 57 | 0.61 (0.49, 0.71) | 0.54 (0.42, 0.65) | 0.45 (0.33, 0.57) |

| 0.59–0.96 | 40 | 0.57 (0.43, 0.71) | 0.55 (0.40, 0.69) | 0.50 (0.35, 0.64) |

| 1.00–2.28 | 19 | 0.62 (0.40, 0.80) | 0.62 (0.39, 0.80) | 0.54 (0.32, 0.75) |

| P-trend | 0.93 | 0.41 | 0.11 | |

| Yogurt without frozen yogurt | ||||

| <0.04 | 62 | 0.56 (0.44, 0.66) | 0.49 (0.38, 0.61) | 0.39 (0.28, 0.51) |

| 0.08–0.16 | 56 | 0.63 (0.51, 0.74) | 0.55 (0.43, 0.67) | 0.44 (0.32, 0.56) |

| 0.22–0.45 | 59 | 0.61 (0.49, 0.71) | 0.55 (0.43, 0.66) | 0.42 (0.31, 0.54) |

| 0.51–2.14 | 55 | 0.60 (0.47, 0.71) | 0.56 (0.44, 0.68) | 0.49 (0.37, 0.62) |

| P-trend | 0.84 | 0.55 | 0.34 | |

aAll analyses were conducted using generalized linear mixed models with random intercepts, a binomial distribution, logit link function and compound symmetry correlation structure.

bData are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI) for the proportion with the indicated outcome, adjusted for total calorie intake, age, BMI, race, smoking status, infertility diagnosis, protocol type, alcohol intake and dietary patterns.

cIncludes cream cheese and other cheese.

dTest for trend were performed using the median level of dairy in each quartile as a continuous variable in the model.

eIncludes skim milk and 1 and 2% milk.

fIncludes frozen yogurt, plain yogurt and flavored yogurt.

*Indicates a P-value <0.05 comparing that quartile versus first quartile.

In a sensitivity analysis restricted to the first ART cycle, to reduce the possibility of misclassification of true dairy intake, total dairy intake was not associated with live birth (Supplementary data, Table SIV). The results were similar to those within the full sample with multivariable-adjusted percentages (95% CI) of 39% (26, 54%), 46% (33, 60%), 40% (28, 54%) and 56% (42, 70%) for increasing quartiles of intake (P, trend = 0.15). Just as in the primary analysis, we observed no association between live birth and intakes of either full-fat or low-fat dairy.

The association between total dairy intake and live birth was significantly modified by women's age (P, interaction = 0.04). Dairy food intake was positively related to live birth among women ≥35 years (P, trend = 0.02) but not among younger women (P, trend = 0.69) (Fig. 1). Across increasing quartiles of dairy intake, the sample size for women <35 years old was 32, 26, 27 and 20, respectively; it was 26, 32, 31 and 38, respectively, for women ≥35 years old. A similar pattern was observed when this stratified analysis was restricted to the first ART cycle. Among women ≥35 years, the multivariable-adjusted live birth rate (95% CI) in the first cycle for increasing quartiles of dairy food intake was 16% (6, 35%), 50% (31, 69%), 35% (20, 54%) and 53% (35, 71%) and for women <35 years, it was 51% (32, 70%), 50% (30, 70%), 52% (32, 71%) and 60% (35, 81%) (P, interaction = 0.06). There was no evidence of effect modification by BMI, or smoking or infertility type (P, heterogeneity >0.05 in all cases).

Figure 1.

Effect modification by age of the association between total dairy intake and live birth per initiated cycle in 232 women (353 cycles) from the EARTH Study.a,b aAll analyses were run using generalized linear mixed models with random intercepts, binomial distribution, logit link function and compound symmetry correlation structure. bData are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI) adjusted for total calorie intake, BMI, race, age, smoking status, infertility diagnosis, protocol type, alcohol intake and dietary patterns are stratified by age. P, interaction = 0.04. n = 127 women (201 cycles) ≥35 years of age and n = 105 women (152 cycles) <35 years of age.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort of women undergoing infertility treatment with assisted reproductive technologies, intake of dairy foods was positively associated with live birth among women ≥35 years of age. This relation did not differ between full-fat and low-fat dairy foods and did not appear to be driven by one single dairy food item. Dairy food intake was not related to ovarian response to stimulation, embryological, implantation or clinical pregnancy outcomes.

The positive association between dairy food intake and live birth in ART was unexpected. Given the inconsistency of the existing literature and suggested biological effects of dairy foods on reproductive function, we anticipated either an inverse relation or no association. Most of the concern for potential adverse reproductive consequences of dairy food consumption on human fertility stem from work on rodent models of the ovary and its function and an early ecological study. Specifically, rodent models show that compared with mice fed a standard diet, galactose-exposed mice exhibit an increased rate of atresia and a decreased state of follicular reserve (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2003).

In an ecological study, Cramer and collaborators compared per capita milk consumption and age-specific fertility rates across 31 countries and found that countries with higher per capita milk consumption had lower age-specific fertility rates (Cramer et al., 1994). Nevertheless, the concerns raised by these studies have not been corroborated by subsequent epidemiologic studies. In a case–control study, women who consumed three or more glasses of milk each day had a 70% lower risk of infertility when compared with women who did not consume milk (Greenlee et al., 2003). Moreover, a prospective cohort study reported no association between total dairy intake and risk of infertility due to anovulation (Chavarro et al., 2007). However, this overall null finding was due to the fact that intake of high-fat dairy foods was associated with a lower risk of ovulatory infertility, and intake of low-fat dairy foods was associated with a higher risk of ovulatory infertility (Chavarro et al., 2007). To our knowledge, no previous studies have evaluated whether intake of dairy foods is related to outcomes of infertility treatment. Therefore, it is possible that dairy foods may have different relations with infertility risk and with infertility treatment outcomes, where many of the potential biological processes necessary for fertility are modified, bypassed or externalized. Clearly, further examination of the relation between dairy food intake and pregnancy outcomes is needed.

It is not clear what biological mechanisms may mediate the observed relation between dairy food intake and live birth among women ≥35 years. In our cohort, compared with women <35, women ≥35 years were more likely to have diminished ovarian reserve (13 versus 1%) and tubal defects (9 versus 5%), but less likely to have ovulatory infertility (5 versus 13%). Intake of dairy foods, and in particular of milk, is known to influence circulating levels of IGF-I (Heaney et al., 1999; Giovannucci et al., 2003) and through this mechanism, it is suspected to exert effects on fetal growth. For example, milk consumption during pregnancy has been associated with higher placental size and offspring size at birth in the Danish National Birth Cohort (Olsen et al., 2007). Similarly, it has been related to higher birthweight resulting from higher fetal weight gain in the third trimester of pregnancy (Heppe et al., 2011). In a case–control study of normal and PCOS IVF patients, among control patients, lower serum insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) during ovarian stimulation was associated with higher likelihood of pregnancy and ongoing pregnancy (Schoyer et al., 2007). These results point out to the relevance of IGFBP-3 in the success of assisted reproduction therapy. The most common points of treatment failure in assisted reproduction are implantation followed by pre-clinical and clinical pregnancy losses. Our findings of a lack of association with pre-clinical end-points and a positive association with live births but not with other clinical end-points are consistent with an interpretation that dairy foods may have a positive influence on pregnancy maintenance. Another equally likely interpretation is that these represent a chance finding.

Although this study contributes to the scarce literature on this topic, it does have limitations. First, while we adjusted for multiple factors including dietary patterns, residual confounding by other variables that were not measured or variables that were poorly measured is still possible. We did not control for number of embryos transferred, because embryo and transfer outcomes could be considered to be potential consequences of dietary exposures in general and of dairy intake in particular, that could mediate in part any observed relation with clinical outcomes following transfer (implantation, clinical pregnancy, live birth). Hence, adjusting for number of embryos could be considered (inadequate) adjustment for an intermediate. Secondly, we cannot rule out the possibility of measurement error given that we used a single diet assessment. However, due to the prospective nature of our study, the error would be expected to be non-differential which would lead to an attenuation of the association. Thirdly, given the study sample size, we had at least 80% statistical power to detect differences between the top and bottom quartile of total dairy intake of 32% for successful implantation, of 29% for clinical pregnancy and 20% for live birth. However, the difference between the top and bottom quartile for total dairy and live birth was 16%. Thus the limited sample size may explain the lack of statistically significant associations of dairy intake with live birth and other clinical outcomes. Finally, these results may not be generalizable to women without known fertility problems. On average, women in our study consumed 2.2 servings of dairy per day while adult women in NHANES reported lower intakes (1.3 servings per day) (Beydoun et al., 2008). However, women in this study are comparable with women in fertility clinics nationwide and therefore results could be informative to women undergoing infertility treatment (Chandra et al., 2014). Strengths of this study include its prospective design, the use of a previously validated diet assessment questionnaire, as well as the study size and complete follow-up which allowed us to evaluate live birth as the main study outcome rather than ongoing pregnancy rate.

In conclusion, there was a positive association between total dairy intake and live birth among women ≥35 years of age undergoing ART. These findings further suggest that dietary factors may impact treatment outcomes among women undergoing infertility treatment. However, the lack of previous data and of a known biological mechanism linking dairy intake to infertility treatment outcomes calls for caution when interpreting these results and for additional work to corroborate or refute them.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/.

Authors’ roles

J.E.C. and M.C.A. designed the research project and had primary responsibility for final content; M.C.A. analyzed data; J.E.C. and M.C.A. wrote the manuscript; P.L.W. and J.E.C. provided statistical expertise; Y.H.C., A.J.G., P.L.W., D.L.W., I.S., R.H. and J.E.C. reviewed the manuscript and provided comments/edits. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants R01-ES009718 and R01ES000002 from NIEHS, P30 DK046200 from NIDDK, and T32HD060454 from NICHD. M.C.A. was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 DK 007703-16 from NIDDK.

Conflict of interest

M.C.A. is currently employed at the Nestlé Research Center and completed this work while at the Harvard School of Public Health. The other authors declare having no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants whose continued dedication and commitment make this work possible and the research nurses Jennifer B. Ford, B.S.N., R.N. and Myra G. Keller, R.N.C. and B.S.N.

References

- Bandyopadhyay S, Chakrabarti J, Banerjee S, Pal AK, Goswami SK, Chakravarty BN, Kabir SN. Galactose toxicity in the rat as a model for premature ovarian failure: an experimental approach readdressed. Hum Reprod 2003;18:2031–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun MA, Gary TL, Caballero BH, Lawrence RS, Cheskin LJ, Wang Y. Ethnic differences in dairy and related nutrient consumption among US adults and their association with obesity, central obesity, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1914–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility service use in the United States: data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 1982-2010. Natl Health Stat Rep 2014;73:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavarro JE, Rich-Edwards JW, Rosner B, Willett WC. A prospective study of dairy foods intake and anovulatory infertility. Hum Reprod 2007;22:1340–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer DW, Xu H, Sahi T. Adult hypolactasia, milk consumption, and age-specific fertility. Am J Epidemiol 1994;139:282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daxenberger A, Ibarreta D, Meyer HHD. Possible health impact of animal estrogens in food. Hum Reprod Update 2001;7:340–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Peláez B, Ferrer-Lorente R, Gómez-Ollés S, Fernández-López JA, Remesar X, Alemany M. Technical note: measurement of total estrone content in foods. Application to dairy products. J Dairy Sci 2004;87:2331–2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskins AJ, Colaci DS, Mendiola J, Swan SH, Chavarro JE. Dietary patterns and semen quality in young men. Hum Reprod 2012;27:2899–2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskins A, Afeiche M, Wright D, Toth T, Williams P, Gillman M, Hauser R, Chavarro J. Dietary folate and reproductive success among women undergoing assisted reproduction. Obstetr Gynecol 2014;124:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannucci E, Pollak M, Liu Y, Platz EA, Majeed N, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Nutritional predictors of insulin-like growth factor I and their relationships to cancer in men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevent 2003;12:84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee AR, Arbuckle TE, Chyou PH. Risk factors for female infertility in an agricultural region. Epidemiology 2003;14:429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser R, Meeker JD, Duty S, Silva MJ, Calafat AM. Altered semen quality in relation to urinary concentrations of phthalate monoester and oxidative metabolites. Epidemiology 2006;17:682–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney RP, McCarron DA, Dawson-Hughes B, Oparil S, Berga SL, Stern JS, Barr SI, Rosen CJ. Dietary changes favorably affect bone remodeling in older adults. J Am Diet Assoc 1999;99:1228–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppe DH, van Dam RM, Willemsen SP, den Breeijen H, Raat H, Hofman A, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW. Maternal milk consumption, fetal growth, and the risks of neonatal complications: the Generation R Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BL, Williams JW. Chapter 19. Evaluation of the Infertile Couple. In: Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, Halvorson LM, Bradshaw KD, Cunningham FG, Calver LE (eds). Williams Gynecology. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford SL, Sundaram R, Schisterman EF, Sweeney AM, Barr DB, Rybak ME, Maisog JM, Parker DL, Pfeiffer CM, Louis GMB. Higher urinary lignan concentrations in women but not men are positively associated with shorter time to pregnancy. J Nutr 2014;144:352–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen SF, Halldorsson TI, Willett WC, Knudsen VK, Gillman MW, Mikkelsen TB, Olsen J, Consortium, a. T. N. Milk consumption during pregnancy is associated with increased infant size at birth: prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:1104–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape-Zambito DA, Roberts RF, Kensinger RS. Estrone and 17β-estradiol concentrations in pasteurized-homogenized milk and commercial dairy products. J Dairy Sci 2010;93:2533–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine and Practice Committee of Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Criteria for number of embryos to transfer: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2013;99:44–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:1114–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, Stampfer M, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Willett WC. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18:858–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoyer KD, Liu H-C, Witkin S, Rosenwaks Z, Spandorfer SD. Serum insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) in IVF patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: correlations with outcome. Fertil Steril 2007;88:139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle SR, Speed FM, Milliken GA. Population marginal means in the linear model: an alternative to least square means. Amer Statistician 1980;34:216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Swarts WJ, Mattison DR. Galactose inhibition of ovulation in mice. Fertil Steril 1988;49:522–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo E, Lopez-del Burgo C, Ruiz-Zambrana A, Donazar M, Navarro-Blasco I, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, de Irala J. Dietary patterns and difficulty conceiving: a nested case-control study. Fertil Steril 2011;96:1149–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Agriculture Fact Book 2001–2002. Washington, DC, USA: Government Printing Office, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Hiza HAB, Bente L, Fungwe T. Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. Home Economics Research Report Number 59. Nutrient content of the U.S. food supply: Developments between 2000 and 2006, 2011.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture ARS. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 25. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page, 2012.

- Vujkovic M, de Vries JH, Lindemans J, Macklon NS, van der Spek PJ, Steegers EAP, Steegers-Theunissen RPM. The preconception Mediterranean dietary pattern in couples undergoing in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatment increases the chance of pregnancy. Fertil Steril 2010;94:2096–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett W. Nutritional Epidemiology, 3rd edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.