Abstract

Children of Latino immigrants in the United States encounter ecological stressors that heighten their risk for depressive symptoms, externalizing behavior, and problems in school. Studies have shown that affirming parent–child communication is protective of child depressive symptoms and accompanying problems. The purpose of this study was to assess the efficacy of an adapted mother–child communication intervention for Latino immigrant mothers and their fourth- to sixth-grade children delivered after school. The intervention, Family Communication (“Comunicación Familiar”), was delivered at children’s elementary schools in six sessions lasting 2 hr each. Significant improvements were found in children’s reports of problem-solving communication, with their mother and mothers’ reports of reduced family conflict. Strengths of the intervention are improved mother–child communication, acquisition of communication skills that can transfer to relationships within the classroom, and a design that allows delivery by nurses or other professional members of the school support team.

Keywords: school-based intervention, protective, parent–child communication, depressive symptoms, Latino, Mexican immigrant, efficacy

Latino children and adolescents in the United States experience depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation at rates much higher than their Euro and African American counterparts (Cowell, Gross, McNaughton, Fogg, & Ailey, 2005; Choi, Meininger, & Roberts, 2006). Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported rates of depressive symptoms for Latino youth at 32.6% versus 28.5% for all youth (Eaton et al., 2012). Ecological factors contributing to depressive symptoms in Latino youth include stress within the family system, economic disadvantage, acculturation challenges, and others (Bond, Toumbourou, Thomas, Catalano, & Patton, 2005; Martinez, McClure, Eddy, & Wilson, 2011). School nurses are concerned about student’s depressive symptoms because of their potential impact on academic achievement, interpersonal relationships, participation in activities, and behavior at school (Jaycox et al., 2009; Roosa et al., 2011).

Depressive symptoms can be exhibited as internalizing or externalizing behaviors (Davis, 2005). Internalizing behaviors include lack of energy, disinterest in school, social withdrawal, and excessive sleepiness. Students with internalizing behavior may forget or miss homework assignments, prefer not to engage in class activities, have higher rates of absenteeism, and consequently earn lower grades. Externalizing behaviors are exhibited as lack of interest in school, agitation, disruptive behavior, and aggression. Students with externalizing behaviors are at increased risk for violence, truancy, and wrongdoing against others. Both types of depressive symptoms are associated with lower performance in school. Researchers have identified risk and protective factors associated with depressive symptoms in Latino youth and recommend strategies for reducing risk by strengthening protective factors (Martinez & Eddy, 2005; Roosa et al., 2012; Sale et al, 2005).

Family Communication as Protective for Children

Parent–child communication is associated with children’s mental health and social development. Affirming communication can strengthen parent–child relationships and protect against mental health symptoms (Cowell, McNaughton, Ailely, Gross, & Fogg, 2009; Black & Lobo, 2008). Affirming communication is characterized by empathy, being available to children, listening, and confirms children’s strengths, self-esteem, and promotes feelings of safety and acceptance (Gonzales et al., 2011; Schrodt, Ledbetter, & Ohrt, 2007). Conversely, incendiary communication is harmful to children’s self-esteem and is harsh, demeaning, accusatory, and controlling (Davidson & Cardemil, 2009; McKinney & Renk, 2011). Children who perceive communication with their parents as incendiary are at greater risk for depressive symptoms, aggression, and risky behaviors. Relationships between family communication and children’s mental health symptoms are true for all families regardless of ethnicity (Bond et al, 2005; Schrodt, Ledbetter, & Ohrt, 2007).

Positive mental health and positive family relationships are linked to academic well-being for Latino youth and decreased delinquent behavior. In a study of 278 Latino youth, social support from parents, teachers, and peers (as measured by a support checklist) was related to higher academic achievement (DeGarmo & Martinez, 2006). Importantly, of all social support relationships, support from parents was the strongest predictor of academic success. In a survey of high school students in the southwestern region of the United States, students who committed delinquent acts such as theft, vandalism, or antisocial behavior were significantly more likely to perceive a lack of communication with their families (Davalos, Chavez, & Guardiola, 2005).

In a randomized clinical trial, a family problem-solving program for Mexican immigrant families was tested using simple steps to address problems in families related to immigration stress (Cowell et al., 2009). In the intervention group, the results indicated improvements in children’s school work and health conceptions as well as mothers’ report of family problem-solving communication. Children reported improvements in depressive symptoms that were nearly significant (p =.055). The researchers concluded that more focused problem-solving communication training could produce greater improvements.

Communication training for parents and children can provide a protective buffer for children by improving communication problem-solving skills and reducing emotionally harmful communication (Riesch et al., 1993). Further, family communication is amenable to change through acquiring new skills such as listening, empathy, problem solving, conflict resolution, and the ability to promote discussions of common family beliefs and values.

Prevention Programs

Researchers have identified preadolescence (10–12 years) as an ideal time to strengthen parent–child communication (Eccles, 1999; Roosa et al., 2011) prior to multiple changes that occur in adolescence. During these years, children expand their capacity for conceptual thinking, self-reflection, and problem solving and are developmentally able to learn new communication skills. In addition, preadolescent children enjoy time with parents: a situation that is likely to change or become more stressful as they grow older. There is evidence that interventions can improve parent–child communication (Riesch et al., 1993); however, communication programs offered in schools focus on strategies to help parents talk with their children about substance abuse, violence, and sexual health. Interventions to specifically promote and strengthen parent–child communication, which is a known protective factor for youth mental health (Ackard, Newmark-Sztainer, Story, & Perry, 2006; Schrodt et al., 2007; Spoth, Neppl, Goldberg-Lillehoj, Jung & Ramisetty-Mikler, 2006) are not available. Given the many ecological risks for Latino youth, parent–child communication training can equip parents and children with skills to strengthen their relationship and improve communication in other settings. Prevention programs exist to reduce risk and promote positive parenting, but few have been adapted to address the language, culture, and values of Mexican immigrant parents and their children.

The study reported here is an efficacy evaluation of a mother–child communication intervention adapted for low literacy Mexican immigrant mothers and their fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-grade children. The adaptation was done in partnership with a community advisory committee of 10 mother–child dyads and took place at a local elementary school. Further information about the adaptation can be found in another article (McNaughton, Cowell, & Fogg, 2013).

Research Aims

The aim of this research is to assess trends in improved mother–child communication and depressive symptoms for fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-grade children after a mother–child communication intervention (“Comunicación Familiar”) in a randomized clinical trial.

Methods

The study was a randomized clinical trial. All procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Setting

The setting for the study was four urban elementary schools in a large Midwestern city. All schools were within a 4.5-mile radius of each other. Schools were located in ethnically diverse, low-income neighborhoods with large Latino populations (48–80% of students in the schools were Latino). Over 90% of students in all schools qualified as low income and were eligible to receive free or reduced price lunches (Illinois State Board of Education, n.d.). Schools were matched geographically by size of student body and percentage of Latino students and were then randomly assigned to intervention or control.

Participants and Recruitment

Recruitment criteria included mother with a child in fourth, fifth, or sixth grade. Only mothers born in Mexico were eligible for the study, regardless of the time spent in the United States. Children in special education classes were excluded.

School-based study coordinators, including social workers or community workers, were assigned by principals at each school to assist with recruitment. School coordinators contacted eligible participants via phone or in person to introduce them to the study. Members of the research team also recruited participants at parent meetings, report card pick up days, and open house. Mothers who were interested in learning more about the study signed forms to request more information. A bilingual project assistant collected the forms and called mothers to answer questions and make appointments to obtain informed consent and baseline data collection.

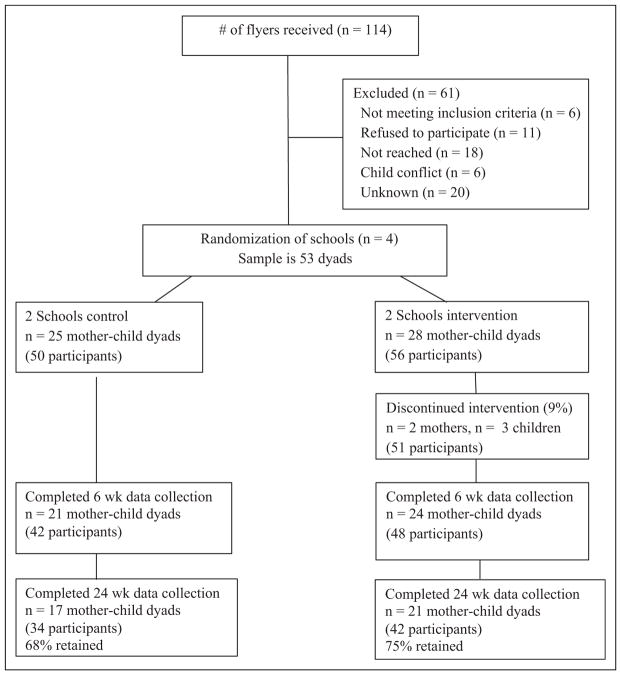

Forty-six percent of mothers who signed information forms enrolled in the study. Reasons for nonenrollment included not meeting inclusion criteria (n =6), refused to participate (n =11), not reached (n =18), conflict with child’s schedule (n =6), and unknown (n =20). Fifty-three mother–child dyads (25 intervention and 28 control) were recruited and enrolled for the study based on an anticipated large effect size (d =0.83; Cohen, 1988) in reducing incendiary communication as obtained in Riesch et al.’s (1993) earlier work (see Figure 1, CONSORT table).

Figure 1.

CONSORT table.

Intervention

In the first phase of the study, the intervention was adapted for Spanish-speaking, low-literacy Mexican immigrant women and their fourth- to sixth-grade children. Mexican immigrant mothers and their children served as an advisory group to the researchers in making the adaptation. The intervention name chosen by the advisory group was Family Communication: Parents and Kids Who Listen. Description of the procedures used to adapt the intervention is reported elsewhere (McNaughton et al., 2013). The intervention is a manual-guided, mental health promotion, communication skill-building program appropriate for use in schools and designed to be delivered by school nurses, social workers, or teachers. The Family Communication intervention consists of 12 hr (6 group meetings, 2 hr each) of small group skill-building sessions with mother–child dyads and is adapted from Riesch et al.’s (1993) Mission Possible: Parents and Kids who Listen program (McNaughton et al., 2013).

The intervention took place after school in a classroom or the school library. Groups consisted of 7–10 mother–child dyads. Fathers were not included based on the recommendations and requests of mothers in earlier focus groups. Mothers stated that they would be able to speak more freely without fathers present.

All sessions began with a large group meeting of mothers and children. Group leaders reviewed content from the previous week and introduced new material. Mothers and children broke into separate groups to practice new skills with their peers and then reconvened to practice in mother–child dyads. Group activities included informal discussion, role-playing, observation, and practicing communication skills. Children’s breakout groups also included playing games and artwork. Large group and mother’s sessions were conducted in Spanish with clarification in English when requested. Simple PowerPoint presentations (in Spanish and English) were used as topic outlines and the number of slides per session ranged from 10 to 18. Sessions were summarized with an informal verbal true–false quiz to reinforce session content. Mothers were given a handbook to take home (as recommended by the advisory committee; McNaughton et al., 2013) in Spanish and English with handouts and written material from each of the six sessions.

Five personnel were needed for each session: a group leader, an assistant leader, a children’s group leader, a child care provider for younger siblings, and a helper to distribute materials and help participants sign in.

Interventionists and Program Materials

Nurses and social workers were recruited as group leaders and assistants for the intervention. All were Latinas who were bilingual in English and Spanish and had a minimum of a bachelor’s degree. Group leaders and assistants participated in a 2-day training session led by the principal investigator. The training followed the intervention manual and included practicing skills.

Outcome Measures

All outcome measures were available in English and Spanish.

Child depressive symptoms

Children’s depressive symptoms were assessed using the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985). The CDI is a 27-item survey based on the Beck Depression Inventory and was developed for use with children aged 8 to 13 years. Scores for items range from 0 (no report of this symptom) to 2 (more severe experience of this symptom). Total scores can range from 0 to 54, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Children with scores of 19 or above on the CDI were referred for further evaluation as recommended by Kovacs (1992). The α reliability score was .81. Validity of the instrument for this population is supported by significant correlations with variables associated with child depressive symptoms, including teacher reports of poor work habits in school (r =.23), child health conceptions (r =−.65), and child global self-worth (r = −.49; Cowell et al., 2009).

Child health conceptions

Children’s health conceptions were measured by the Child Health Self-Concept Scale (CHSC; Hester, 1984). The CHSC is a self-report instrument containing 45 items and includes 5 subscales measuring (1) satisfaction with home life, (2) emotional health, (3) physical health, (4) peer relationships, and (5) sleeping patterns (Hester, 1984). The self-report instrument is designed for children to rate their own health beliefs and health behaviors. Positive health beliefs and behaviors have been found to be protective against problem behaviors (Jessor, Van Den Bos, Vanderryn, Costa, & Turbin, 1995). Respondents rate each item from 1 (representing negative health self-concept) to 4 (representing positive health self-concept). Higher scores indicate healthy beliefs and behaviors. The total score can range from 45 to 180. The α coefficient for this study is .72.

Mother–Child Communication

Mother–child communication was measured using the Family Problem Solving Communication (FPSC) instrument (mother report; McCubbin, McCubbin, & Thompson, 1998) and the Parent-Adolescent Communication Inventory (PACI, mother and child report; Barnes & Olson, 1985). Both measures (FPSC and PACI) assess communication on two dimensions (affirming/open and incendiary/problem).

FPSC

The FPSC is a 10-item measure of problem solving in families experiencing stress. Respondents rate their agreement with items about their family communication as 0 =false, 1 =mostly false, 2 =mostly true, and 3 =true. Higher scores indicate more positive communication. Validity of the measure with Mexican immigrant mothers was demonstrated in our previous work, showing significant correlations in the expected direction with family hardiness (r =.50) and mother’s mental health (r = −.32); α reliability is .72.

PACI

The PACI is a 20-item instrument completed by mothers and children to report perceptions of communication with each other. The instrument is available in Spanish and validity for the Latino population is reported by the authors (Barnes & Olson, 1985). The instrument assesses communication on two dimensions: open and problem. Respondents rate each item as 1 =strongly disagree, 2 =moderately disagree, 3 =neither agree nor disagree, 4 =moderately agree, or 5 =strongly agree. Higher scores indicate more positive communication. Reliability of the total instrument was .63 for children and .76 for mothers. Subscale reliability scores for the “Open” subscale were .78 for children and .79 for mothers. Reliability scores for the “Problem” communication subscale were .62 for children and .64 for mothers.

Family conflict subscale of Hispanic stress inventory

Family conflict was measured by the Family/Culture Conflict subscale of the Hispanic Stress Inventory (HSI), immigrant version (Cervantes, Padilla, & Salgado de Snyder, 1991). The sub-scale contains 12 items and respondents rate the stressful-ness of each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 =not at all stressful, 2 =somewhat stressful, 3 =moderately stressful, 4 =very stressful, 5 =extremely stressful). Higher scores indicate greater levels of stress. Content and construct validity are reported by the authors. The α reliability coefficient for the Family/Culture Conflict subscale was .78 in the current study.

Secondary Outcome and Feasibility Measures

Feasibility was assessed by enrollment and attendance rates, participant satisfaction, and ability to deliver the intervention in a school setting (McNaughton et al., 2013).

Procedures

Informed consent

Mothers signed the informed consent and children signed the assent form at the first data collection meeting. Consent documents were written in English and Spanish and were read to mothers and children in the language of their choice to account for varying levels of literacy. Paper copies of the consent documents were provided for participants to read along.

Data collection

Most data collectors were bilingual Latina social workers, nurses, and project assistants. One data collector was not Latina but had a master’s degree in Spanish and was a fluent speaker. Data collectors received a 6-hr training that focused on reading the surveys aloud in English and in Spanish. Questions regarding meaning or intent of a word or phrase were discussed and clarified in the group to maximize linguistic equivalence. In addition, data collection procedures were discussed and each data collector received a data collection manual. Confidentiality and mandated reporting of intention to hurt self or others and suspected abuse were emphasized. The approved research protocol spelled out steps for the research team to intervene if depressive symptom scores were at or above cut points requiring referral for further evaluation. Steps for referral to protective services were provided if abuse was suspected.

Data collection took place on Saturdays in community locations convenient to families, such as neighborhood elementary schools, churches, and a local college. Data were collected on weekends and in the community, rather than homes, due to preferences of the advisory group (McNaughton et al., 2013) and the availability of the mothers. In some cases, data were collected during the week at schools when families were not able to attend Saturday data collection.

Mothers were able to select a data collection time that was most convenient to them and their families. Child care was provided on-site for younger children. Initial data collection lasted about 90 min. Subsequent assessments lasted about 60 min. Mothers and children were interviewed in separate rooms using surveys with English and Spanish translations. Surveys were read to participants in the language of their choice. In addition, mothers and children were provided a copy of the survey to read while they were being interviewed. At the end of the survey, mothers received a US$30 gift card to a local store and children received a book worth about US$7.

To maximize attendance at the data collection sessions, mothers were called and reminded of their appointment several days prior to and the day before their session. In addition, if mothers were late for their appointment, they were called and reminded to come. Most women were easily contacted via their cell phones.

Data Analysis

Analyses were based on an intent-to-treat approach. Therefore, all data were analyzed for both groups regardless of the intervention dose received. Intent to treat is meant to reflect variable participation as experienced in real practice.

Descriptive statistics were obtained on the sample data for all research variables. In addition, one-way analyses of variance and chi-square analyses on the demographic and baseline research measures were performed between the intervention and control groups to determine whether the groups were comparable. Data were examined in two ways: the first (between-group effects) comparing the intervention and control groups and the second (within-group effects) examining improvement in the intervention group without adjusting for control group effects. The second approach was used because the powerful control group effects contaminated our estimates of intervention effectiveness.

Results

Demographic characteristics of mothers and children can be found in Table 1. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between intervention and control conditions.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Children | |

| Gender | |

| Boys | 27 (50.9) |

| Girls | 26 (49.1) |

| Age, mean (range) | 11 (9–14) |

| Mothers | |

| Age, mean (range) | 36.9 (26–50) |

| Education | |

| Middle school or less | 39 (73) |

| High school or more | 14 (27) |

| Marital status | |

| Yes | 43 (88.1) |

| No | 6 (11.3) |

| Living with partner | 4 (7.5) |

| Language preference | |

| English | 2 (3.8) |

| Spanish | 51 (96.2) |

Retention

Retention was assessed in two ways: (1) percentage of participants completing time 3 data collection and (2) rate of intervention attendance. The intervention attendance rate for mothers and children was 78%, or 4.8 of 6 sessions offered, indicating that participants attended and therefore received most of the intervention content. Retention of participants at each stage of the study can be found in the CONSORT table (Figure 1). Detailed description of implementation feasibility can be found in a separate publication (McNaughton et al., 2013).

Between-Group Outcomes

All between-group comparisons (control and intervention) were made between Time 1 (baseline) and Time 3 (24 weeks). Children in the intervention group reported significant improvements in problem-solving communication (as measured by the PACI) with their mothers when compared to control group children (see Table 2). Similarly, intervention children reported improvements in depressive symptoms and health self-concept with small/moderate effect sizes (d =.29 and .36, respectively; Cohen, 1988) as compared to control children. Mothers in the intervention group reported significant improvement in family conflict (as indicated by lower scores) as measured by the Family Conflict Subscale of the HSI and compared to control group mothers. Positive trends in improved family problem-solving communication and reduced incendiary communication were found between intervention and control group mothers at moderate/large effect sizes (d =.62 and .52, respectively).

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Differences Across Time and Group (N =53 Mother–Child Dyads).

| Time 1

|

Time 3

|

F

|

Sig

|

Effect Size

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | w/in groupa; b/w groupb | w/in group; b/w group | w/in group; b/w group |

| Child | |||||||

| Com total | 68.32 (7.9) | 69.53 (9.5) | 69.96 (7.9) | 70.50 (7.8) | 2.00; 1.05 | .145; .353 | .12; −.08 |

| Com PS | 28.88 (5.6) | 29.14 (6.5) | 30.24 (5.8) | 31.25 (6.0) | 0.73; 3.25 | .486; .048* | .33; .13 |

| Com open | 39.44 (6.0) | 40.38 (6.5) | 39.76 (6.7) | 39.89 (5.5) | 1.12; 0.73 | .335; .477 | −.08; −.14 |

| CHSC | 124.39 (9.5) | 122.31 (11.6) | 129.22 (7.4) | 130.56 (8.6) | 13.58; 0.41 | .000**; .249 | .89; .36 |

| CDI | 10.21 (4.8) | 10.61 (6.9) | 7.92 (7.0) | 6.61 (5.1) | 8.82; 0.81 | .000**; .453 | .67; .29 |

| Mother | |||||||

| Com total | 79.55 (7.7) | 72.27 (11.4) | 81.04 (7.7) | 73.41 (11.2) | 0.48; 0.04 | .619; .969 | .12; −.04 |

| Com PS | 35.12 (5.9) | 32.13 (7.3) | 36.16 (6.5) | 33.94 (7.7) | 4.25; 0.58 | .019; .548 | .26; .11 |

| Com open | 44.43 (4.0) | 40.14 (6.8) | 43.20 (5.2) | 39.86 (6.6) | 1.12; 2.24 | .335; .112 | −.05; .17 |

| Fam conflict | 17.36 (4.6) | 19.18 (8.9) | 17.00 (4.7) | 16.93 (4.8) | 2.67; 3.73 | .078; .034* | .36; .30 |

| PS com total | 24.20 (4.1) | 21.49 (5.5) | 23.68 (3.9) | 23.68 (4.1) | 9.18; 2.78 | .000**; .072 | .50; .62 |

| PS com aff | 13.00 (2.0) | 12.05 (2.3) | 12.44 (2.0) | 12.11 (2.2) | 1.93; .38 | .155; .680 | .03; −.24 |

| PS com inc | 3.80 (2.6) | 5.32 (3.5) | 3.20 (2.2) | 3.32 (2.5) | 8.84; 1.72 | .000**; .185 | .74; .52 |

Note. CDI =Children’s Depression Inventory; CHSC =Child Health Self-Concept; Com Tot =Communication Total: Parent-Adolescent Communication Inventory (PACI); Com PS =Communication Problem Solving (PACI); Com Open =Communication Open (PACI); Com P =Communication Problem (PACI); Fam conflict =Family/Culture Conflict subscale of the Hispanic Stress Inventory (HSI); PS Com Total =Family Problem Solving Communication Total (FPSC); PS com aff =Problem-Solving Communication, Affirming (FPSC); PS com inc =Problem-Solving Communication, Incendiary (FPSC).

w/in group =intervention group comparisons between Times 1 and 3;

b/w group =comparisons between intervention and control groups at Time 3.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Within-Group Outcomes

Significant within-group improvements were found for intervention mothers and children between Time 1 and Time 3. Children reported improved depressive symptoms and health self-concept. Mothers reported improved problem-solving communication on two measures (FPSC/total and PACI/total) and reduced incendiary communication. No improvements were found in children’s communication (total) or children’s open communication as measured by the Parent Adolescent Communication Inventory. Similarly, no improvements were found in mothers’ communication total and open communication scores.

Discussion

Efficacy

Significant improvements were found in children’s problem-solving communication with mothers and mothers’ reports of family conflict between intervention and control conditions. Trends in improved depressive symptoms and child health self-concept were found between children in intervention and control conditions as calculated by small to moderate effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). Similarly, between-group improved effect size differences were found for mothers in problem-solving communication, family conflict, and reduced incendiary communication. Effect size differences were small to moderate.

Significant within-group improvements were found for mothers and children in both intervention and control conditions. Improvements for children were found in depressive symptoms and health conceptions. Improvements for mothers were found in problem-solving communication and reduced incendiary communication. In other words, the control condition also improved in children’s mental health and mother–child communication. Consequently, we explored possibilities as to why this may have occurred. Specifically, we were concerned that our data collection procedures may have contaminated the outcomes.

Data were collected 3 times for each mother–child dyad. Each data collection included face-to-face interviews with Latina school social workers, depression screening and referral, and a videotaped mother–child problem-solving activity. From our experience working with Latina immigrants, we know that many endure unusual hardships; for this reason, we employed Latina social workers to conduct the data collection interviews. Our goal was to assure that participants felt comfortable and respected when they were interviewed. In retrospect, although data collectors were trained to not provide “therapy,” some women told their stories in the interviews and cried as they did this. Women reported family stressors such as violence in the home, conflict with extended family members, contracting sexually transmitted diseases from their husbands, problems with children, and lack of access to routine health care. These problems were disclosed in response to open-ended questions on the demographic questionnaire during baseline data collection.

One mother from the control condition told the principal investigator that during the first videotaped discussion, she and her daughter decided on a problem to work on and that this has helped their relationship. In this situation, although the dyad did not receive the intervention, the opportunity to discuss a problem in front of a camera may have motivated them to problem solve and adopt new behaviors. It is also possible that exposure to the communication inventories (PACI and FPSC) heightened awareness of positive communication patterns.

Adjustment of future data collection procedures will include elimination of open-ended questions. Data collection training and guidelines will reinforce skills to redirect participants who tell stories or stray from the topic. Additionally, we will not videotape mother–child problem-solving scenarios, as these provided opportunities to practice problem solving over the course of the study. We will continue to refer participants with depressive symptom scores above established cut points for further evaluation.

The location of the intervention within children’s schools was convenient for families and was the preferred location for mothers (McNaughton et al., 2013). The intervention began shortly after the end of the school day and included snacks for participants and free child care for younger siblings. Challenges involved limited space, conflict with after school activities, and school attendance schedules that required us to be flexible in delivering the intervention.

Partnership with principals provided the foundation for positive relationships and collaboration with school personnel. Principals provided opportunities for recruitment during parent meetings, open houses, and other school activities. In addition, principals connected us with school social workers and parent volunteers to assist with recruitment. Principals also facilitated access to space within schools for delivering the intervention.

Although principals worked with us to support recruitment, several circumstances presented barriers in recruiting mothers for the study. In one school, a parent started a rumor that our research team was gathering personal information that could be used for deportation. Our bilingual community partners from the schools reported back to us that mothers were more afraid after the February 2010 immigration law was passed in Arizona; therefore, they did not want to speak with us. Some schools did not want us to place recruitment posters in the hallways or speak at bilingual parent meetings because participation was limited to Mexican immigrants, thereby excluding other ethnic groups. Because potential participants were afraid of being identified as “Mexican immigrants” in a research study, in the future we will expand recruitment criteria to Latina mothers and children regardless of immigration status or country of origin.

This study and many others reported an inverse relationship between affirming, supportive family communication and children’s mental health symptoms (Trudeau, Spoth, Randall, Mason, & Shin, 2012). Additional research demonstrates associations between children’s mental health symptoms and academic achievement (Jaycox et al., 2009). Future research is needed to explore the efficacy of family communication interventions during preadolescence on improved mental health symptoms and academic achievement.

Schools are under mounting scrutiny to meet academic testing standards that demand strict dedication of resources to meet this end. From an ecological perspective, multiple factors influence children’s success in school, including children’s mental health and family relationships. Challenges to promoting student achievement must be met from a whole-child perspective with recognition that children with depressive symptoms and/or problems at home are less likely to meet their academic potential. Mental health promotion and family strengthening programs can be a part of achieving this goal. An additional challenge is to identify school outcomes that are sensitive to the intervention.

Implications for School Nursing

School nurses and social workers are in a position to identify Latino students and families at risk for acculturative stress. The Family Communication intervention can be successfully delivered in a school setting by school nurses, teachers, or social workers as a multidisciplinary team. Opportunities to collaborate with other school health team members are in keeping with the focus of the Affordable Care Act and enlarge the pool of interventionists available when resources are limited (Cowell, 2013). Teachers who are trained by the program leaders can model communication skills in the classroom. Communication skills acquired from the program can be applied at home, in schools, and in daily interactions with others.

School nurses are case finders for many family-centered problems. In that role, school nurses can initiate the efforts to address those problems. Although specific roles in school settings are often negotiated and limit interdisciplinary practice, this study provides evidence that practice is effective. In this study, the program was developed and managed by school nursing researchers. The collaboration between disciplines often blurred the lines of specific expertise among disciplines and serves as a model for interdisciplinary practice.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the National Institute for Nursing Research, R21-NR0 10617-01A1.

Footnotes

Author’s Note

Dr. Cowell is the executive editor of The Journal of School Nursing, Dr. Mayumi Willgerodt, a member of the Editorial Advisory Board, served as an associate editor for this submission, so that the blind review would not be compromised.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C. Parent-child connectedness and behavioral and emotional health among young adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes HL, Olson DH. Parent-adolescent communication and the circumplex model. Child Development. 1985;56:438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Black K, Lobo M. A conceptual review of family resilience factors. Journal of Family Nursing. 2008;14:33–55. doi: 10.1177/1074840707312237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond L, Toumbourou JW, Thomas L, Catalano RF, Patton G. Individual, family, school and community risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms in adolescents: A comparison of risk profiles for substance abuse and depressive symptoms. Prevention Science. 2005;6:73–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-3407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Salgado de Snyder N. The Hispanic stress inventory: A culturally relevant approach to psychosocial assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1991;3:438–447. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.3.3.438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Meininger J, Roberts RE. Ethnic differences in adolescents’ mental distress, social stress, and resources. Adolescence. 2006;41:263–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cowell JM. Interprofessional practice and school nursing. The Journal of School Nursing. 2013;29:327–328. doi: 10.1177/1059840513501468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell JM, Gross D, McNaughton D, Fogg L, Ailey S. Depression and suicidal ideation among Mexican American school-aged children. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2005;19:77–94. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.19.1.77.66337. Retrieved from http://www.cinahl.com/cgi-bin/refsvc?jid=2320&accno=2005118467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell JM, McNaughton D, Ailey S, Gross D, Fogg L. Clinical trial outcomes of the Mexican American problem solving program (MAPS) Hispanic Health Care International. 2009;7:178–189. doi: 10.1891/1540-4153.7.4.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos DB, Chavez EL, Guardiola RJ. Effects of perceived parental school support and family communication on delinquent behaviors in Latinos and non-Latinos. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;11:57–68. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson TM, Cardemil EV. Parent-child communication and parental involvement in Latino adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Davis NM. Depression in children and adolescents. The Journal of School Nursing. 2005;21:311–317. doi: 10.1177/10598405050210060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Martinez CR. A culturally informed model of academic well-being for Latino youth: The importance of discriminatory experiences and social support. Family Relations. 2006;55:267–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries. 2012;61:1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS. The development of children ages 6 to 14. The Future of Children. 1999;9:30–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Coxe S, Roosa MW, White RMB, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Saenz D. Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican-American adolescent’s mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester NO. Child’s health self-concept scale: Its development and psychometric properties. Advances in Nursing Science. 1984;7:45–55. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illinois State Board of Education. [Accessed February 9, 2007];Illinois report card. n.d Available at: http://iirc.niu.edu.

- Jaycox LH, Stein BD, Paddock S, Miles JNV, Chandra S, Meredith SS, Burnam MA. Impact of teen depression on academic, social and physical functioning. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e596–e605. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Van Den Bos J, Vanderryn J, Costa FM, Turbin MS. Protective factors in adolescent problem behavior: Moderator effects and developmental change. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:923–933. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The children’s depression inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s depression inventory: Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, Eddy JM. Effects of culturally adapted parent management training on Latino youth behavioral health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;74:841–851. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, McClure HH, Eddy JM, Wilson DM. Time in U.S. residency and the social, behavioral, and emotional adjustment of Latino immigrant families. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Science. 2011;33:323–349. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin MA, McCubbin HI, Thompson AI. Family problem solving communication (FPSC) In: McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA, editors. Family assessment: Resiliency, coping and adaptation-Inventories for research and practice. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin; 1988. pp. 639–686. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney C, Renk K. A multivariate model of parent-adolescent relationship variables in early adolescence. Child Psychiatry and Early Development. 2011;42:442–462. doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton DB, Cowell JM, Fogg L. Adaptation and feasibility of a communication intervention for Mexican immigrant mothers and children in a school setting. Journal of School Nursing. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1059840513487217. Published online before print April 24, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesch SK, Tosi CB, Thurston CA, Forsyth DM, Kuenning TS, Kestly J. Effects of communication training on parents and young adolescents. Nursing Research. 1993;42:10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, O’Donnell M, Chan H, Gonzales NA, Zeiders KH, Tein JY, Umana-Taylor A. A prospective study of Mexican American adolescents’ academic success: Considering family and individual factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41:307–319. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9707-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Zeiders KH, Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Tein J, Saenz D, Berket C. A test of the social development model during the transition to junior high with Mexican American adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0021269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sale E, Sambrano S, Springer JF, Pena C, Pan W, Kasim R. Family protection and prevention of alcohol use among Hispanic youth at high risk. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36:195–205. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrodt P, Ledbetter AM, Ohrt JK. Parental confirmation and affection as mediators of family communication patterns and children’s mental well-being. Journal of Family Communication. 2007;7:23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Neppl T, Goldberg-Lillehoj C, Jung T, Ramisetty-Mikler S. Gender-related quality of parent-child interactions and early adolescent problem behaviors: Exploratory study with Midwestern samples. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:826–849. [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau L, Spoth R, Randall GK, Mason WA, Shin C. Internalizing symptoms: Effects of a preventive intervention on developmental pathways from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41:788–801. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9735-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]