Summary

Aim of the study

Stillman’s cleft is a mucogingival triangular-shaped defect on the buccal surface of a root with unknown etiology and pathogenesis. The aim of this study is to examine the Stillman’s cleft obtained from excision during root coverage surgical procedures at an histopathological level.

Materials and method

Harvesting of cleft was obtained from two periodontally healthy patients with a scalpel and a bevel incision and then placed in a test tube with buffered solution to be processed for light microscopy.

Results

Microscopic analysis has shown that Stillman’s cleft presented a lichenoid hand-like inflammatory infiltration, while in the periodontal patient an inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia was identified.

Conclusion

Stillman’s cleft remains to be investigated as for the possible causes of such lesion of the gingival margin, although an inflammatory response seems to be evident and active from a strictly histopathological standpoint.

Keywords: Stillman’s cleft, recessions, gingival margin, histological analysis, inflammation

Introduction

Stillman’s cleft is a mucogingival triangular-shaped defect predominantly seen on the buccal surface of a root, first described by Stillman as a recession related to occlusal trauma, either associated with marginal gingivitis or with mild periodontitis (1). It can be found as a depression or as a sharply defined fissure extending up to 5–6 mm of length (Fig. 1). This particular type of ulcerative gingival recession occurs as single or multiple cleft and it can be classified as simple (one direction shape) or composed (multiple and differently directed shape) (2, 3). Other possible etiological factors are assumed to be periodontal inflammation (2), which leads to proliferation of the pocket epithelium into the gingival corium and its subsequent anastomosis with the outer epithelium (4). In addition, the traumatic tooth-brushing and the incorrect use of the interdental floss have been described among the possible causes (5, 6). A recent systematic review concluded that although the majority of the observational studies confirmed a relationship between tooth brushing and gingival recessions the data to support or question the association are inconclusive (7). To date, the etiology and pathogenesis of this defects remain unclear even though the assumptions are related to chronic factors that ulcerate the epithelium and healing occurs through the anastomosis of the external and internal epithelium in the gingival sulcus, creating a triangular defect (8). When flossing trauma is involved, superficial gingival tissue clefts are ‘red’ because the injury is confined within connective tissue. In this case the lesion is reversible: flossing procedures have to be interrupted for at least 2 weeks and chemical plaque control only (i.e. chlorexidine rinses) should be performed. If the cleft appears ‘white’ the whole connective tissue thickness is involved and the root surface becomes evident; in this case the gingival lesion is irreversible (9, 10).

Figure 1.

Stillman’s cleft.

In case of Stillman’s clefts, home oral hygiene could become very difficult to be performed and bacterial or viral infections may induce the formation of a buccal probing pocket of sufficient depth to reach the periapical areas of the tooth. Sometimes a delayed diagnosis is made only when an endodontic abscess occurs (10). The prognosis of the clefts is variable: they can heal uneventfully or remain as superficial lesions combined with deep periodontal pockets.

In 2013 Pilloni showed how a laterally moved, coronally advanced technique could modify and eliminate this kind of anatomical lesion. He demonstrated that such surgical approach was effective in treating an isolated Stillman’s cleft and the result remained stable over a 5-year period (11).

Analysis of gingival clefts indicate an apically-directed spread of an inflammatory exudate through the gingival connective tissues, with concurrent epithelial resorptive and proliferative reactions, with collagen resorption being mediated by an hydrolytic enzymatic activity (8).

The aim of this study was to examine the Stillman’s cleft histological features in two different patients and compare them with the clinical aspects (healthy vs non healthy periodontal tissues).

Case report

Two patients with in common the presence of an asymptomatic Stillman’s cleft on a vital and stable element, without any restoration, were selected for the study. They presented with two different periodontal conditions: patient A was periodontally healthy, meanwhile patient B was healthy but previously treated for mild periodontitis. Patient B showed a deeper lesion (5 mm) than patient A (2 mm).

The surgical protocol consisted of the excision of the cleft, as indicated by previously validated techniques (12), in order to create a better manageable contour of the gingival recession for subsequent treatment. Preparation of the surgical site followed the same surgical protocol of the treatment of a single gingival recession with a subepithelial connective tissue graft, that allows the coverage of the exposed root surface (11). Patients received ibuprofen twice daily for three days and a 0.12% chlorhexidine rinse every 12 hours for 7 days. No systemic antibiotics were used.

The tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours and than were oriented in order to correctly identify the cleft and sectioned perpendicularly longitudinally by 2 mm cuts. The biopsies were sampled in toto in two histological biocasettes: the representative sample of cleft was placed within the first one (one or two samples) and the lateral part of surgical biopsies into the second one. Finally, they were embedded in paraffin wax and 4 μm serial sections were cut at different levels and stained with haematoxylin and eosin for each block. The slides were examined with a Nikon Eclipse E1200 light microscope and pictures taken with a Nikon camera system.

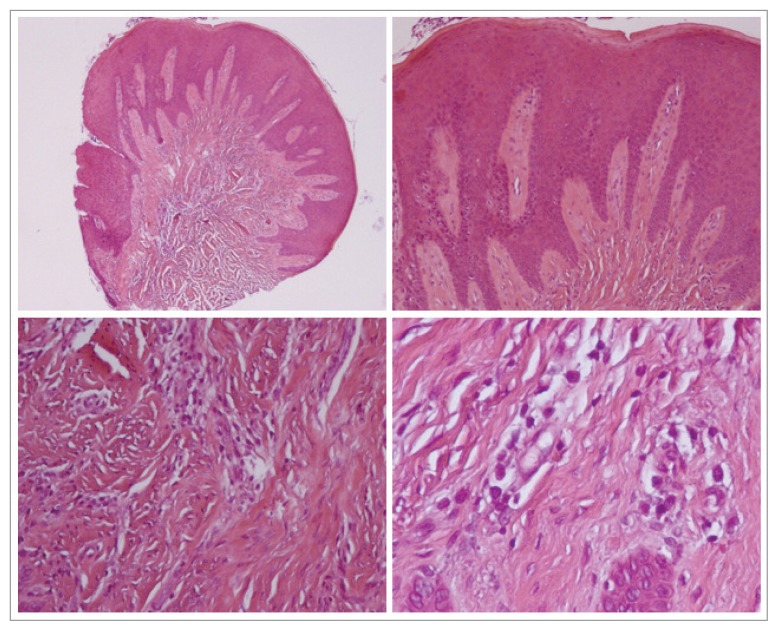

Patient A: at scanning magnification, a lichenoid band-like inflammatory infiltrate is observed with focal epithelial ulceration corresponding to cleft floor.

At higher magnification, the epithelium shows reactive atypia with many mitoses, spongiosis, acantosis and occasional diskeratotic cells.

The inflammatory infiltrate is mainly constituted by small lymphocytes with sligthly irregular nuclei and only scarce plasma cells. The lamina propria shows fragmentation of elastic fibers (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Histological analysis patient A.

Patient B: a different aspect resembling inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia could be seen. In fact, at scanning electron microscopy, a pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying sclerotic lamina propria has been observed.

At higher magnification, far from the lymphocyte-rich inflammation, mainly plasma cells could be seen around small vessels (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Histological analysis patient B.

Discussion and conclusion

To date, only a few cases have been published on the etiology and pathogenesis of Stillman’s clefts and with the aim of explaining their histological features. This may depend both on the rarity of such lesion and on patient’s agreement in accepting surgical procedures to modify it, particularly in asymptomatic cases. Moreover, in recent years, literature has focused primarily on different surgical techniques aimed at the resolution of esthetics with primarily the aim of seeking at the maintenance of the health of periodontal tissues. For this reasons, we decided to investigate the histological characteristics of two different Stillman’s clefts and correlate them with their clinical presentation. According to our preliminary results, the case A (cleft from healthy periodontal tissues) showed histological features resembling acute and mild gingivitis. The first one with predominantly T small lymphocytes was sided in correspondence of the cleft and the mild type with few plasmacells around the cleft in apparent clinically healthy gingiva. Case B (periodontal disease-treated associated cleft) showed histological features similar to chronic gingivitis or mild periodontitis with a predominantly B cells response with only few plasma cells and chronic scarring of lamina propria.

This preliminary study aimed at also defining a predictable methodology to obtain proper amount of soft tissue from the lesion to then fully obtain comprehensive histological evaluation. The future perspectives are to analyze the cleft sample also on an ultrastructural level by transmission electron microscopy to better describe the presence and amount of both collagen and other matrix components. Moreover, an immunohistochemical study should be carried out in order to understand the cellular composition and the expression of inflammatory mediators within the lesion. For these reasons, a larger sample is needed to reach a better understanding of the pathogenesis of this common lesion.

References

- 1.Stillman PR. Early clinical evidences of diseases in the gingival and pericementum. J Dent Res. 1921;3:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Box HK. Gingival cleft and associated tracts. N Y State Dent J. 1950 Jan;16(1):3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tishler B. Gingival clefts and their significance. Dent Cosm. 1927;69:1003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman HM, Schluger S, Fox L, Cohen DW. Periodontal Therapy. ed 3. St Louis: C. V. Mosby Co; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirschefeld I. Traumatization of soft tissues by tooth-brush. Dent Items Int. 1933;55:329. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greggianin BF, Oliveira SC, Haas AN, Oppermann RV. The incidence of gingival fissures associated with tooth brushing: crossover 28-day randomized trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:319–326. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajapakse PS, McCracken GI, Gwynnett E, Steen ND, Guentsch A, Heasman PA. Does tooth brushing influence the development and progression of non-inflammatory gingival recession? A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:1046–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novaes AB, Ruben MP, Kon S, Goldman HM, Novaes AB., Jr The development of the periodontal cleft. A clinical and histopathologic study. J Periodontol. 1975 Dec;46(12):701–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1975.46.12.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zucchelli G. Chirurgia estetica mucogengivale. Quintessenza Edizioni. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zucchelli G, Mounssif I. Periodontal plastic surgery. Periodontology. 2000;68:333–368. doi: 10.1111/prd.2015.68.issue-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilloni A, Dominici F, Rossi R. Laterally moved, coronally advanced flap for the treatment of a single Stillman’s cleft. A 5-year follow-up. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2013;8(3):390–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallmon W, Waldrop T, Houston G, Hawkins B. Flossing clefts. Clinical and histologic observations. J Periodontol. 1986;57:501–504. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.8.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]