Abstract

The use of selenomethionine (MSe)-p-cyanophenylalanine (FCN) pairs to probe protein structure is demonstrated. MSe quenches FCN fluorescence via electron transfer. Both residues can be incorporated recombinantly or by peptide synthesis. Time-resolved and steady-state fluorescence measurements demonstrate that MSe-FCN pairs provide specific local probes of helical structure.

Fluorescence measurements are widely employed in studies of protein dynamics, folding, stability, and aggregation.1, 2 Trp has the highest quantum yield of the naturally occurring fluorescent residues in proteins, but its quantum yield depends on a variety of factors, and proteins often contain multiple Trp residues. Both factors can make structural interpretation of Trp fluorescence changes ambiguous. Trp-His pairs have been used to probe secondary structure and rely on the quenching of Trp fluorescence by the His sidechain.3 However, only the protonated form of the His sidechain is an effective quencher of Trp fluorescence, limiting the approach to pH values at which the imidazole group is protonated. The covalent attachment of fluorescent dyes is another popular approach, particularly for use as Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) pairs, however the method requires selective attachment of two dyes and often requires the introduction of Cys mutations. Furthermore, while typical dyes are very bright, they can perturb the properties of the protein of interest as they are usually built around large polyaromatic cores. In many cases FRET pairs have large R0 values making it difficult to probe smaller local changes in structure. For these applications short range quenchers are desired.4 A simple non-perturbing approach which involves a fluorophore that can be selectively excited and which provides easily interpreted structural information would be a useful addition to the arsenal of fluorescent methods.

We demonstrate that selenomethionine (MSe) and p-cyanophenylalanine (FCN) (Fig. 1a) can be used as a minimally perturbative fluorescent probe of protein structure. The pair has been used to examine short oligoproline peptides.5 FCN is the cyano analogue of Tyr. The residue can be incorporated into proteins recombinantly using 21st pair technology or by solid phase peptide synthesis and represents a conservative substitution for Tyr or Phe.6–11 FCN fluorescence can be selectively excited in the presence of Tyr and Trp.6 The quantum yield of FCN is controlled by solvation; fluorescence is high when the cyano group forms a hydrogen bond in a polar protic solvent and is low when it is buried in a hydrophobic environment.6–12 FCN fluorescence is also quenched by deprotonated His and Lys as well as via FRET to Tyr or Trp.6, 7, 10, 11, 13 The fluorescence lifetime decay of free FCN is single exponential and has been reported to be 7.5 ns for a G-FCN-G tripeptide.5 In contrast, the fluorescence decay of Trp is multi-exponential, even for simple peptides. MSe is the selenium analogue of Met and has been widely used in multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) phasing for X-ray crystallography and has seen some applications as an NMR probe.14 The residue can be easily incorporated into proteins in very high yield via recombinant expression and is also compatible with solid phase peptide synthesis. MSe quenches FCN fluorescence via electron transfer.5 The short range of the quenching effect suggests that FCN-MSe pairs could be used to design fluorescence-based probes of local secondary structure. Here we illustrate its use to monitor helical structure.

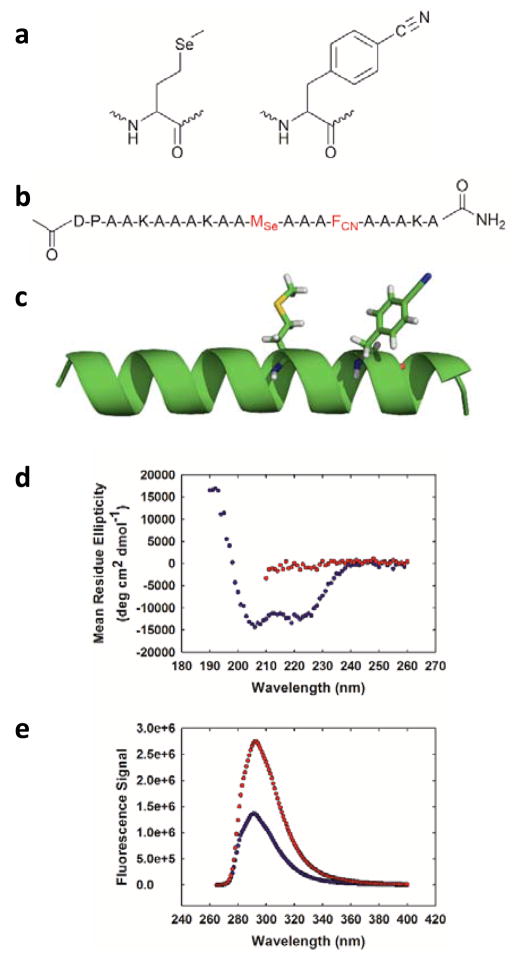

Fig. 1.

(a) Structure of selenomethionine (MSe) and p-cyanophenylalanine (FCN). (b) Sequence of the designed helical peptide. The MSe and FCN residues are coloured red. (c) Ribbon diagram of an idealized helix showing the interaction of FCN and MSe where the residues are located at positions i and i+4. (d) CD spectra of the peptide in buffer (blue) and in 8 M urea (red). (e) Fluorescence emission spectra of the α-helical state (blue) and the 8 M urea unfolded state (red). Experiments were conducted in 10 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.5 and 25 °C. The concentration of peptide in the samples was 25 μM.

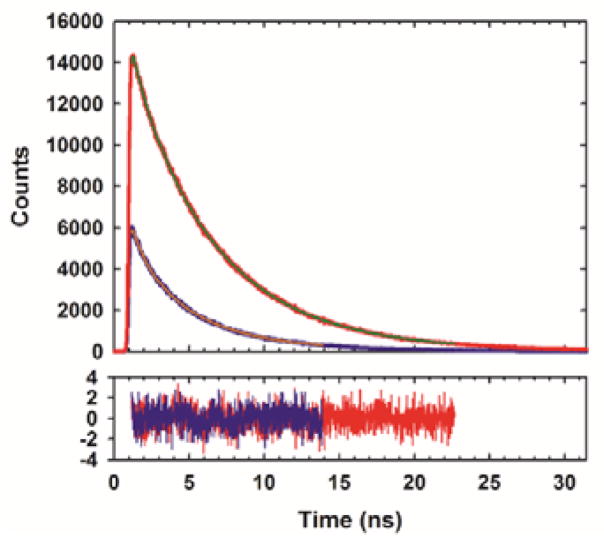

As a first test of the proposed approach we designed a 21-residue α-helical polypeptide (Fig. 1b, c). MSe is prone to oxidation, however, we did not detect significant oxidation products after incubating the peptide in buffer (Fig. S1). Reducing agents can be used and oxygen excluded by degassing if this is an issue. The polypeptide contains an FCN residue at position 16 and an MSe residue at position 12. The i, i+4 separation brings the two residues into proximity in the α-helical state. Circular dichroism (CD) shows that the peptide is helical in buffer at 25 °C (Fig. 1d) and is much less structured in 8 M urea. The mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm is −12,600 deg cm2 dmol−1 in buffer which corresponds to an estimated helical content of 38% (Supporting Information). In the urea unfolded state the mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm is −1,400 deg cm2 dmol−1. FCN fluorescence is high in the urea unfolded state, but is reduced twofold in the α-helical state (Fig. 1e). We next conducted time-resolved fluorescence lifetime measurements. The integrated area under the fluorescence decay curve for for the folded state is much smaller than for the unfolded state, consistent with quenching of the FCN fluorescence in the helical state. The fluorescence decay for the folded state is fit by two components with lifetimes of 4.12 and 0.93 ns with relative amplitudes of 0.73 and 0.27, respectively (Fig. 2). The multi-exponential decay suggests the presence of two populations with different separations between the sidechains of the two residues. Bi-exponential decays have been reported for an MSe-FCN dipeptide indicating the effect is likely local in origin.5 The fluorescence decay of the urea unfolded state is fit by two components with lifetimes of 5.72 and 1.12 ns with relative amplitudes of 0.86 and 0.14, respectively. Analysis of the data using a maximum entropy approach yields very similar time constants and relative amplitudes (Fig. S2).

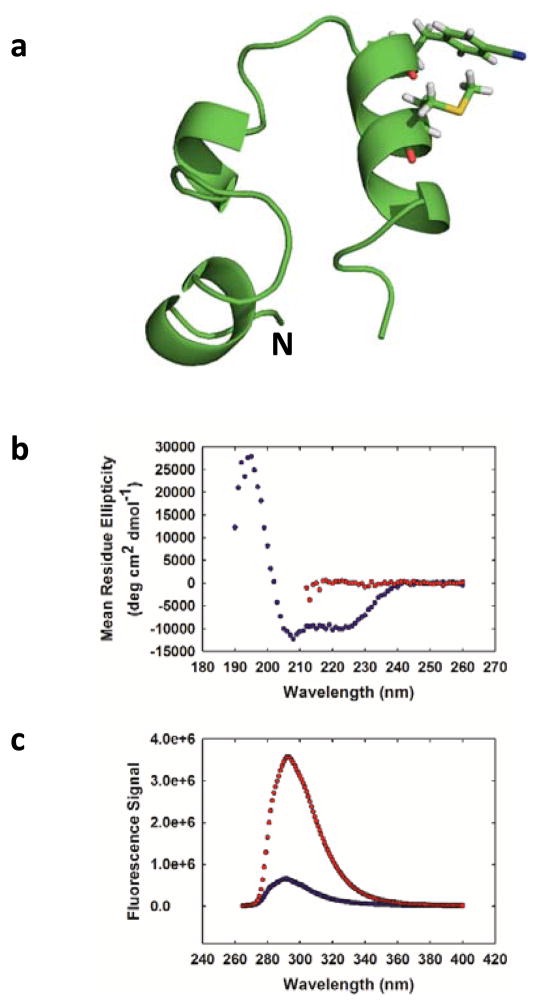

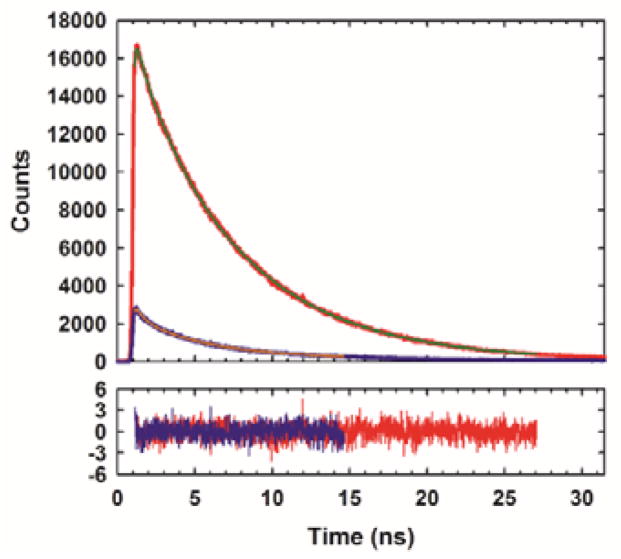

Fig. 2.

Time-resolved fluorescence decays for the α-helical state (blue) and the urea unfolded state (red). Decays were fit using two exponentials. The residuals are also plotted.

We next examined the applicability of the pair to follow helix formation in a globular protein. The 36-residue villin headpiece helical subdomain (HP36) was chosen as a model system (Fig. 3a). HP36 is a three-helix protein which contains a single Trp at position 24 in the third helix.15–17 The helical subdomain is part of the villin protein and the numbering used here denotes the first residue in our construct as residue 1. The domain has been widely used for studies of protein folding, dynamics and stability.18–27 We replaced Trp-24 with FCN and residue 28 with MSe. These sites are located on the surface of the protein on the C-terminal helix. The CD spectrum of the construct is very similar to that reported for wild-type HP36 indicating that these surface substitutions do not perturb the structure.18 The hydrophobic core of HP36 contains three closely packed Phe residues, leading to characteristic ring current shifted resonances in the 1H-NMR spectrum which is indicative of the folded state.17, 27, 28 These peaks are observed in the 1H-NMR spectrum of the FCN-MSe variant, providing additional evidence that the substitutions do not perturb the fold (Fig. S3). The HP36 FCN-MSe variant, like the wild-type, exhibits a sigmoidal thermal unfolding transition (Fig. S4). The i, i+4 spacing of residues leads to efficient quenching in the folded state, but not in the urea unfolded state. The FCN intensity is six fold less in the folded state relative to the urea unfolded state (Fig. 3c). The larger change in fluorescence observed for HP36 compared to the peptide reflects the fact that HP36 is fully folded in buffer, while the designed helical peptide is only partially structured. Thus a significant fraction of the helical peptide is unfolded and does not experience effective fluorescence quenching. Fluorescence lifetime studies confirm that there are significant differences in FCN fluorescence between the folded and unfolded states; the integrated area under the time-resolved decay is much less for the folded state relative to the urea unfolded state. The folded state exhibits a bi-exponential decay with time constants of 4.96 and 0.72 ns. The relative amplitudes of the components are 0.68 and 0.32, respectively. The urea unfolded state also exhibits a bi-exponential decay with time constants of 6.72 and 1.21 ns, and relative amplitudes of 0.87 and 0.13, respectively (Fig. 4). Analysis of the data using a maximum entropy approach yields very similar time constants and relative amplitudes (Fig. S5).

Fig. 3.

(a) Ribbon diagram of HP36 showing the location of the FCN and MSe residues. The N-terminus is labelled. (b) CD spectra of the protein in buffer (blue) and in 10 M urea (red). (c) Fluorescence emission spectra of the protein in buffer (blue) and in 10 M urea (red). Experiments were performed in 20 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.0 and 25 °C. Protein concentration was 25 μM.

Fig. 4.

Time-resolved fluorescence decays for the protein in buffer (blue) and in 10 M urea (red). Decays were fit using two exponentials. Residuals are plotted below.

In principle FCN fluorescence quenching can be used to monitor thermally induced protein unfolding. However, like Trp, the quantum yield of FCN is temperature dependent and decreases with increasing temperature (Fig. S6). This will lead to potential problems with pre- and post-transition baselines, and the ability to unambiguously detect the protein unfolding transition will depend on the magnitude of the fluorescence change due to unfolding.1, 3, 29

His-Trp pairs have been used as probes of α-helical structure and rely on the ability of a protonated His sidechain to quench Trp fluorescence, but this approach is limited to pH values where a significant fraction of the imidazole sidechain is protonated.3, 30–32 The quenching of FCN fluorescence by His is also pH dependent; in the case of FCN, a deprotonated His sidechain is an effective quencher, but a protonated His sidechain is not.13 This is not an issue with the MSe approach, and effective quenching is observed at both high and low pH (Fig. 5).

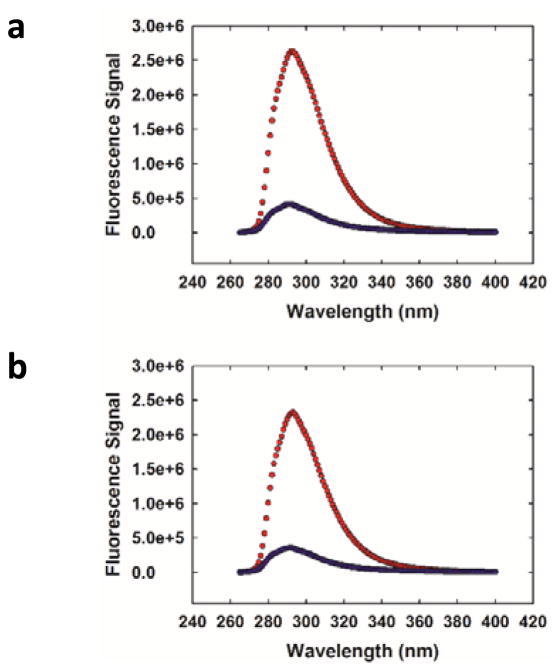

Fig. 5.

MSe quenching of FCN is pH independent. Fluorescence emission spectra in buffer (blue) and in 10 M urea (red) at (a) pH 5.0 (b) pH 8.5. Experiments were conducted in 20 mM sodium phosphate at 20 °C. Protein concentration was 17 μM.

In summary, we have demonstrated that FCN-MSe pairs provide a simple probe of local helical structure in polypeptides and globular proteins. Here we have used equilibrium studies to demonstrate the utility of the method, but the pair is also suitable for kinetic folding and unfolding studies, particularly those that involve dilution out of denaturant, such as stopped-flow experiments. The FCN-MSe pair offers several advantages including the ability to selectively excite FCN fluorescence in the presence of Tyr and Trp, the pH independent response, and the conservative nature of the substitution. In the present case, we illustrated the approach by developing local probes of α-helical structure, but the methodology could also probe β-sheet formation. For example, residues located across from each other on two adjacent β-strands will be close in the native state of a protein, but much more distant in the unfolded state and should experience a significant change in fluorescence. The approach is best suited to solvent exposed sites for the FCN residue since burial of the FCN sidechain can quench the fluorescence independent of any MSe effect. However, the choice of a surface site also ensures that the substitution will be minimally perturbing. As noted earlier, FCN fluorescence can be quenched by deprotonated His and Lys and by FRET to Tyr or Trp. Interaction with a deprotonated Lys is unlikely given its pKa, but the presence of a His, Tyr or Trp residue that is in close proximity to the FCN site should be avoided. We anticipate that the approach will be useful for studies of protein folding and dynamics, protein-protein interactions, and protein aggregation. The approach described here is complementary to the use of thioamides as fluorescence quenchers.33, 34 Thioamides offer a quencher localized to the backbone while MSe provides a sidechain based quencher. Thioamides are commonly incorporated by native chemical ligation while MSe is incorporated with standard auxotrophic strains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Feng Gai for his interest and for numerous helpful discussions, and Prof. Erwin London for use of his fluorimeter and helpful discussions. We thank Ms. Rehana Akter for assistance with peptide synthesis, Dr. Bowu Luan for assistance with NMR spectroscopy, and Mr. Junjie Zou for assistance with modelling. This project was initiated based on conversations with Prof. Gai at the NSF sponsored Protein Folding Consortium (MCB-1516959). The work was supported by NSF MCB-1330259 grant to DPR, NIH GM078114 to DPR, NSF MCB-1121942 to OB and NIH GM023303 to C.R. Matthews.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown MP, Royer C. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997;8:45–49. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(97)80156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubelka J, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:625–630. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00519-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahoo H, Roccatano D, Zacharias M, Nau WM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8118–8119. doi: 10.1021/ja062293n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mintzer MR, Troxler T, Gai F. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17:7881–7887. doi: 10.1039/c5cp00050e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tucker MJ, Oyola R, Gai F. Biopolymers. 2006;83:571–576. doi: 10.1002/bip.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tucker MJ, Tang J, Gai F. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:8105–8109. doi: 10.1021/jp060900n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aprilakis KN, Taskent H, Raleigh DP. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12308–12313. doi: 10.1021/bi7010674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L, Xie J, Schultz PG. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:225–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.101105.121507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyake-Stoner SJ, Miller AM, Hammill JT, Peeler JC, Hess KR, Mehl RA, Brewer SH. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5953–5962. doi: 10.1021/bi900426d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers JMG, Lippert LG, Gai F. Anal Biochem. 2010;399:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serrano AL, Troxler T, Tucker MJ, Gai F. Chem Phys Lett. 2010;487:303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taskent-Sezgin H, Marek P, Thomas R, Goldberg D, Chung J, Carrico I, Raleigh DP. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6290–6295. doi: 10.1021/bi100932p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rozovsky S. ACS Symp Ser. 2013;1152:127–142. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bi Y, Cho JH, Kim EY, Shan B, Schindelin H, Raleigh DP. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7497–7505. doi: 10.1021/bi6026314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu TK, Kubelka J, Herbst-Irmer R, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J, Davies DR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7517–7522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502495102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKnight CJ, Matsudaira PT, Kim PS. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:180–184. doi: 10.1038/nsb0397-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brewer SH, Vu DM, Tang Y, Li Y, Franzen S, Raleigh DP, Dyer RB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16662–16667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505432102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao S, Patsalo V, Shan B, Bi Y, Green DF, Raleigh DP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:11337–11342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222245110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glasscock JM, Zhu Y, Chowdhury P, Tang J, Gai F. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11070–11076. doi: 10.1021/bi8012406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubelka J, Chiu TK, Davies DR, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:546–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cellmer T, Henry ER, Kubelka J, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14564–14565. doi: 10.1021/ja0761939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cellmer T, Buscaglia M, Henry ER, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:6103–6108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019552108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiner A, Henklein P, Kiefhaber T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4955–4960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neumaier S, Kiefhaber T. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:2520–2528. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelman H, Gruebele M. Q Rev Biophys. 2014;47:95–142. doi: 10.1017/S003358351400002X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown JW, Farelli JD, McKnight CJ. Protein Sci. 2012;21:647–654. doi: 10.1002/pro.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang M, Tang Y, Sato S, Vugmeyster L, McKnight CJ, Raleigh DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6032–6033. doi: 10.1021/ja028752b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robbins RJ, Fleming GR, Beddard GS, Robinson GW, Thistlethwaite PJ, Woolfe GJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:6271–6279. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y, Barkley MD. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9976–9982. doi: 10.1021/bi980274n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Gilst M, Hudson BS. Biophys Chem. 1996;63:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(96)02181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willaert K, Engelborghs Y. Eur Biophys J. 1991;20:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg JM, Batjargal S, Petersson EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14718–14720. doi: 10.1021/ja1044924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wissner RF, Batjargal S, Fadzen CM, Petersson EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:6529–6540. doi: 10.1021/ja4005943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.