Abstract

The prevalence of anal intraepithelial neoplasia has been increasing, especially in high-risk patients, including men who have sex with men, human immunodeficiency virus positive patients, and those who are immunosuppressed. Several studies with long-term follow-up have suggested that rate of progression from high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions to invasive anal cancer is ∼ 5%. This number is considerably higher for those at high risk. Anal cytology has been used to attempt to screen high-risk patients for disease; however, it has been shown to have very little correlation to actual histology. Patients with lesions should undergo history and physical exam including digital rectal exam and standard anoscopy. High-resolution anoscopy can be considered as well, although it is of questionable time and cost–effectiveness. Nonoperative treatments include expectant surveillance and topical imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil. Operative therapies include wide local excision and targeted ablation with electrocautery, infrared coagulation, or cryotherapy. Recurrence rates remain high regardless of treatment delivered and surveillance is paramount, although optimal surveillance regimens have yet to be established.

Keywords: anal intraepithelial neoplasia, human papillomavirus, carcinoma

The incidence of anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) and anal squamous cell carcinoma has been increasing in the United States. The reported rate of anal cancer has risen to 2 per 100,000 since the advent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS),1 whereas prior to this, the reported incidence was 0.7 per 100,000.2 Although this rate is increasing, it is still a relatively uncommon disease when compared with colon and rectal cancers, which have an incidence rate of 43.9 per 100,000.3 There were an estimated 7,210 new anal cancers diagnosed in 2014 compared with 136,830 new colorectal cancers.3 It is thought that the increasing incidence is related to an increase in anoreceptive intercourse amongst both men and women, an increased number of lifetime sexual partners, and an increased number of men having sex with men.4 5 Historically, women have been more frequently affected by anal dysplasia than males. However, more recent data have demonstrated similar rates amongst both men and women.4 Unlike cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and cervical cancer, it is unknown whether AIN progresses through a spectrum of premalignant lesions before transforming into anal squamous cell carcinoma. Diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance have not been standardized and multiple and confusing sets of terminology further complicate the matter. The objective of this article is to discuss and present the latest techniques and data on screening, surveillance, and treatment of AIN.

History

Extensive research has now shown that there is an association between human papillomavirus (HPV) and AIN.6 7 This, however, was not always the case. In 1912, John T. Bowen first described two patients who had atypical epithelial proliferation of the skin.8 The first case of perianal Bowen's disease was reported by Vickers et al in 1939.9 In 1962, Turell discovered that there was a histologic and biologic difference between perianal skin cancers and anal canal squamous cell carcinomas.10 Oriel and Whimster in 1971 discovered HPV particles in anal squamous cell carcinoma specimens using electron microscopy and helped to establish a link between HPV, AIN, and anal squamous cell carcinoma.11 Dysplasia was first described in 1981 by Fenger and Nielsen12 and their subsequent work helped to establish the vernacular now associated with AIN.2 The more recent AIDS epidemic has spurred additional research into risk factors for developing this disease and for progression of disease.13 14

Nomenclature

Initially, the grading system for dysplasia in anal lesions was classified subjectively by pathologists into three categories: mild, moderate, and severe. As the data on cervical cancer and its association with HPV came into focus, these data were extrapolated to anal lesions and the categories were renamed AIN 1, 2, and 3, respectively.2 Studies showed that AIN 2 had poor pathologic interobserver reliability,15 which had also been demonstrated in the literature for CIN 2.16 17 This led to significant confusion to clinicians hoping to develop a treatment plan, as AIN 2 was often seen as equivocal for preneoplasia. More confusion came when the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) began to promote the use of the term squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL), low grade or high grade. At the same time, the World Health Organization was recommending the use of the previously described AIN terminology. It was the pathology community that recognized the need for standardization in nomenclature. They proposed a two-tiered grading system, eliminating the grade 2 terminology.

HPV infection will take one of the two courses: a transient and self-limited infection or a persistent carrier state associated with progression to cancer. The two-tiered system, then, classified as low-grade SIL (LSIL), corresponding to the transient, self-limited HPV infection, and high-grade SIL (HSIL), corresponding to the chronic, long-standing infection. This two-tiered system is similar to that used for cervical, vaginal, and vulvar lesions.

To help further standardize histologic evaluation and reduce variability, the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology in 2012 recommended the use of the two-tiered LSIL and HSIL grading system. This recommendation has been echoed by multiple other professional societies and agencies.18 Many terms have been used in the literature in the past to describe HSIL, including Bowen disease, AIN 2 or 3, and squamous cell carcinoma in situ. These all describe the same lesion and for the sake of standardization, only HSIL should be used to avoid confusion. The AJCC has also adopted this terminology.19

Epidemiology

It is difficult to know the exact incidence of AIN in the population. It has been changing over time in the AIDS era and with increasing numbers of organ transplant patients. Impaired host cellular-mediated immunity is a strong risk factor for AIN and progression to HSIL.20 21 22

Both men and women infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) show significantly increased rates of AIN and anal cancer. Men who have sex with men (MSM) are ∼ 20 times more likely to develop both HSIL and anal cancer than heterosexuals.23 The prevalence in HSIL in this population is still only 8%, however.24 Additionally, the total number of estimated new cases of invasive anal cancer in 2014 is only 7,210.3 Men who are MSM and are HIV positive have the highest incidence of HPV infection (80.9%) and, in turn, the highest rates of HSIL and squamous cell carcinoma. HPV-16 and 18, which have been associated with higher rates of progression to high-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma, have been detected at higher rates in HIV-positive MSM versus HIV-negative MSM.5 Shiels et al published a meta-analysis in 2009 that showed that the prevalence of HSIL and anal squamous cell carcinoma combined was 29.1% in HIV-positive MSM versus 21.5% in HIV-negative MSM. Additionally, they showed an incidence of 45.9 per 100,000 and 5.1 per 100,000 in those groups, respectively. In the same study, HIV-positive women were also shown to have a seven-fold increased risk of anal cancer versus the general population.25

In a study, Devaraj and Cosman followed 40 HIV-positive men with untreated dysplasia for 130 months. Three of these patients developed anal squamous cell carcinoma and all three developed within a new symptomatic mass.26 This comes to a 7.5% progression rate over 11 years. In another study by Pineda et al, 246 patients being treated for HSIL were followed for a mean of 52 months. Three developed invasive carcinoma and two developing within a new symptomatic mass.27 This is a progression rate of 1.2% over 4 years. This group also showed progression at a comparable rate despite treatment of HSIL. These data suggest that AIN progresses to invasive carcinoma at a very low rate.

HPV and HIV have a clear connection. Patients with HIV are more likely to be infected with multiple strains of HPV.28 HPV infection by itself may have an influence on acquiring HIV, with a significantly higher chance of HIV seroconversion seen in MSM with HPV versus MSM who do not have HPV.29 HPV is more likely to persist in HIV-positive patients and more likely to progress to dysplasia and cancer. This may be related to impaired cellular-mediated immunity.30 This also holds true in the organ-transplant population, where there is an increase in high-grade dysplasia and anal cancer, that is, 10- to 100-fold over the general population,31 but it is still very rare. Again, this appears to be related to the iatrogenic immunosuppression with medications that affect the cellular arm of the immune system.

The Role of Human Papillomavirus

The HPV is by far the most common sexually transmitted disease in the United States. It is considered by experts to be ubiquitous, and it is estimated that all sexually active adults will acquire genital HPV at some point in their lifetime.

HPVs are small double-strained DNA viruses with a predilection for infection in squamous epithelium. There are more than 130 HPV subtypes that have been isolated. Anogenital infections have been linked to ∼30 to 40 subtypes. These can be further subdivided into those that cause mild disease, that is, condyloma, LSIL, and CIN 1 (subtypes 6, 11, 42, 43, and 44), and those that cause HSIL and invasive carcinoma (subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 50, 51, 55, 56, 58, 59, and 68).32 33 The presence of HPV in LSIL has been reported at 88%, and 91% in HSIL.34 35 Subtypes 16 and 18 have been identified most often in high-grade and invasive squamous cell carcinoma lesions.35 This draws a comparison to cervical cancer, where HPV subtypes 16 and 18 have been demonstrated to have a strong association with progression to cervical cancer.33 It is well documented in cervical cancer that these high-risk subtypes become integrated into the host cell genome, leading to overexpression of oncogenes and inhibition of tumor suppressor genes. It is this integration into the genome and the subsequent genetic changes that facilitates the progression to high-grade dysplasia and invasive cancer.36 The proposed sequence of progression from normal to cancer is normal epithelium, LSIL, HSIL, and invasive cancer.

Predictive Factors for Progression to High-Grade AIN and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Several studies have been conducted with follow-up over 20 years, which have reported an overall progression rate from HSIL to invasive carcinoma of 5%.21 37 One of these studies showed progression rates from LSIL to HSIL in 62% of HIV-positive MSM and 36% of HIV-negative MSM,21 but not to the development of anal cancer. The progression of AIN in HIV-negative heterosexual patients is less well understood. One study on women reported that 50% had incidental anal HPV and that 87% of those patients resolved their infections within 1 year.38 In HIV-positive patients, the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy, which has significantly decreased most AIDS-associated cancers, has not been shown to decrease the incidence of high-grade AIN and invasive carcinoma.39 Risk factors that have been postulated for progression to high-grade AIN and invasive carcinoma include smoking, low CD4 counts, high-risk HPV subtypes, and multiple HPV subtype infections.21 28

Pathology

Grossly, AIN can be observed as any of a group of heterogeneous lesions that may appear as papillomas, plaques, papules, or eczematous lesions. Microscopically, it is characterized by increased cellularity, nucleomegaly, pleomorphism, increased nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratio, irregular nuclear borders, and dense chromatin. These changes are limited to the epithelium. In LSIL, these changes are seen in the lower one-third of the epithelium, with the upper one-third normal. Nuclear atypia and abnormal mitotic figures are not features of LSIL. HPV cytopathic changes may also been seen, including koilocytosis, multinucleation, irregular nuclei, and perinuclear cytoplasmic clearing. HSIL, in contrast, shows the changes typical of LSIL but present throughout the middle and upper thirds of the epithelium. HSIL may also demonstrate nuclear atypia and abnormal mitoses. HSIL also shows overexpression of certain biomarkers, including p16. Evaluation by immunohistochemistry can help to differentiate LSIL from HSIL in otherwise equivocal cases.40 41 42

Screening for Anal Dysplasia

Anal Cytology

Screening with anal cytology has been promoted in high-risk patients to help reduce morbidity and mortality by detecting precursor lesions prior to invasive carcinoma. Screening is performed by using a moistened swab to take a blind smear of the anal transition zone.43 Cytologic interpretation is based on the 2001 Bethesda classification.44 Studies have shown mixed results in terms of anal cytology's usefulness as a screening tool. Anal cytology has a sensitivity ranging from 47 to 90% and specificity from 16 to 92%.45 The specificity drops off when a comparison is made to biopsy results. A significant number of cases are upgraded based on the biopsy, with an absolute agreement of 74.7% in one study.46 The presence of atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance within a cytology specimen is upgraded to HSIL on biopsy in 46 to 67% of cases. LSIL on cytology is upgraded to HSIL on biopsy in 56% of cases.46 47 48 49 50 A study by Berry et al compared anal cytology to patients with known HSIL on histology. On anal cytology of these 38 patients, 19 were read as atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance or LSIL and 11 were read as normal.51 Anal cytology has not been shown to have any correlation with histology and, as such, it should not be used in surveillance or treatment plans.

High-Resolution Anoscopy

High-resolution anoscopy is a technique similar to colposcopy that has been adapted to evaluate the anal epithelium.52 When 3% acetic acid is applied to dysplastic tissue, it shows distinct changes, turning acetowhite.53 This color change, while not specific, allows identification of vascular changes associated with LSIL and HSIL. LSILs tend to be raised lesions with branching vascular patterns and HSILs are usually flat lesions with punctate vasculature.54 Lugol's solution is then applied to any lesions that demonstrate uncertain characteristics. Lesions that do not take up Lugol's solution are at higher risk for containing HSIL.55 Lugol's solution is best used in combination with acetic acid, as its accuracy decreases to 33% when used alone.56 Suspicious areas are biopsied for diagnosis and areas of HSIL are typically destroyed.

A 2005 study showed that high-resolution anoscopy correctly predicted normal mucosa 90% of the time and HSIL 75% of the time when compared with biopsy results. Identifying LSIL by high-resolution anoscopy proved more difficult in this study, with 50% of biopsy-proven LSIL being missed by high-resolution anoscopy.57 A second study compared high-resolution anoscopy with biopsy results in both HIV-positive and -negative MSM and demonstrated a positive predictive value of only 49% for HSIL.58 Rates of persistence and recurrence of HSIL after treatment with high-resolution anoscopy and excision or ablation remain high. Pineda et al showed a recurrence rate after high-resolution anoscopy and local excision of 57%.27 Chang et al showed a 79% recurrence of HSIL in HIV-positive patients by 12 months after treatment. Subsequent treatment resulted in a 66% recurrence rate.59 These high rates of recurrence and persistence demonstrate the field effect created throughout the tissue by HPV infection.

Nonoperative Management

Regular Surveillance

Because the natural history and progression rate of AIN to invasive anal cancer are uncertain (but most likely low and slow), it has been suggested that most patients only require close observation. This approach necessitates short-interval follow-up and patients only undergo interventions in the event they develop a visible ulcer or palpable lesion.60 Several studies have evaluated the use of regular surveillance in HIV-positive patients with known HSIL. In one of these studies, 11% of patients developed invasive carcinoma within 7 years.26 Another study showed a progression rate of 15%.36 These studies involved small sample sizes and were retrospective in nature, relying heavily on chart review and documentation. A study assessing progression of LSIL to HSIL demonstrated progression in 62% of HIV-positive patients and 36% of HIV-negative patients.21

In 2015, a retrospective study of serial high-resolution anoscopy versus regular surveillance with standard anoscopy was published by Crawshaw et al.61 The study included 424 patients with biopsy-proven AIN, with 220 undergoing serial high-resolution anoscopy and 204 undergoing traditional regular surveillance. Three patients progressed to anal cancer, two in the regular surveillance group, and one in the high-resolution anoscopy group. All patients who progressed to cancer were noncompliant with follow-up and therapy. The overall 5-year progression rate was 6% for regular surveillance and 4.5% for high-resolution anoscopy.61 These results suggest that as long as patients are followed closely with regular office visits every 3 to 12 months for history and physical examination with standard anoscopy and biopsy of new or suspicious lesions, it is rare that they progress to cancer regardless of method used and the cost, and value and morbidity of high-resolution anoscopy should be further evaluated versus expectant management.

Topical Treatments

Topical imiquimod cream, 5%, is an immunomodulator that activates Toll-like receptor 7, resulting in release of proinflammatory cytokines that activate both the cellular and humoral immune system. It is administered three times per week for 16 weeks. The patient applies the cream to the perianal skin at night, and then washes it off the following morning. While some studies describe application within the anal canal, imiquimod is only indicated for use on the anal margin. Side effects of use are irritation, burning, erosions, and infection. A meta-analysis by Mahto et al found a complete response in 48% of AIN patients treated with imiquimod and a partial response rate of 34%. They found a recurrence rate of 34% within a follow-up period of 11 to 39 months.62 Because of the risk for recurrence, development of new lesions, and progression of disease, surveillance remains crucial for patients treated with imiquimod. Imiquimod should be considered as an adjunct to more directed therapies.60

Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has also long been described for treatment of AIN. It is typically used for 9 to 16 weeks.60 Studies have shown response rates up to 90% with recurrence in 50%.60 A study was conducted in 2010 of HIV patients treated with topical 5-FU, which was applied into the anal canal with an applicator for 16 weeks. This study showed a complete response in 39%, partial response in 17%, and no response in 37%. A total of 50% of patients with a complete response recurred by 6 months.63 Again, because of high recurrence rates, topical 5-FU should be considered as an adjunct to directed therapy and patients must undergo surveillance during and after treatment.

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy involves administration of a photosensitizer, either oral or intravenous. This is taken up by the tissues of the anal canal and administration of a specific wavelength of light causes activation of the sensitizer and destruction of the affected cells.27 57 Small studies have demonstrated that this procedure is safe and can result in downgrading of HSIL to LSIL; however, follow-up in these studies has been short and data on recurrence are not available. Additionally, this can only be performed once per patient due to the development of hypersensitivity after the first dose. No large, prospective studies have been performed.

Vaccination

The vaccine against HPV subtypes 16 and 18 has been shown to be safe and should be considered for high-risk patients.60 There have been multiple vaccine combinations developed and the literature for cervical, vulvar, and vaginal disease has been promising, showing nearly 100% efficacy against high-grade lesions when administered to uninfected women younger than 26 years of age.64 A vaccine against HPV subtypes 6, 11, 16, and 18 has been developed and has shown some efficacy against anal HPV. In 2011, Palefsky et al published a randomized, double-blind study of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine versus placebo in MSM. The presence of clinically evident condyloma or lesions consistent with AIN on anoscopy excluded patients from this study. They showed efficacy in 50.3% of patients in the intention to treat group and 77.5% of patients in the per protocol group. Rates of AIN per 100 person-years were 17.5 in the placebo group and 13 in the vaccine group. The rate of AIN related to HPV subtypes 6, 11, 16, or 18 was reduced by 54.2% in the intention to treat group and by 74.9% in the per protocol group. Risk of persistent infection with HPV subtypes 6, 11, 16, or 18 was reduced by 59.4 and 94.9%, respectively.65 Although the vaccines against HPV are safe and have shown some efficacy (although not in preventing anal cancer), further studies need to be performed to determine specific indications and optimal timing of administration.

Operative Management

Wide Local Excision

Wide local excision was initially described by Strauss and Fazio in 1979.66 The extent of resection is determined either by macroscopically negative margins or by preoperative mapping of the perianal skin, anal verge, and dentate line with punch biopsies. A total of 24 routine biopsies are taken and additional biopsies of abnormal appearing areas. Historically, frozen sections were used to guide intraoperative decision making regarding extent of excision; however, it has been found to be relatively inaccurate and has largely been abandoned. Wide local excision creates an average defect of 17.4 cm2 when performed for AIN.67 Smaller defects may be closed primarily or allowed to heal by secondary intention. Larger defects may require split-thickness skin grafting or flap coverage for closure. In cases where extensive wide local excision is required, temporary diversion may be required to allow adequate healing of the perineum.68 Additional long-term complications include anal stenosis and fecal incontinence.

Despite the size of the defect and the morbidity associated with removing significant portions of uninvolved healthy tissue, the recurrence rate ranges from 9 to 63%.60 69 This is likely due to the fact that while wide local excision removes the dysplastic tissue, the rest of the perianal and anal canal tissue still harbors HPV and is at risk for future dysplasia. It should also be remembered that the disease that is trying to be prevented, anal cancer, is curable without any surgery in 85 to 90% of cases. It is difficult to recommend a procedure with high morbidity for prevention of a disease with a low rate of progression when the primary treatment of the target disease, invasive anal squamous cell carcinoma, is nonsurgical with low morbidity.

Targeted Destruction

Targeted destruction of HSIL after identification with high-resolution anoscopy aims to destroy AIN lesions while not exposing patients to the risk of morbidity associated with wide local excision. This can be performed with electrocautery, infrared coagulation, or cryotherapy. A small prospective study of HIV-positive and HIV-negative males treated with electrocautery targeted destruction after identification of lesions by high-resolution anoscopy showed a recurrence rate of 0% for HIV-negative patients and 79% for HIV-positive patients during a short follow-up period of 2 years. Those that recurred were treated with high-resolution anoscopy, biopsy, and repeat targeted destruction. None of the patients progressed to anal cancer with this treatment, but follow-up was shorter than would be expected to detect progression. Also, the group at the highest risk for progression to invasive cancer had nearly universal recurrence in the short term, calling into question the clinical benefit to “targeted” therapy. No patients developed anal stenosis, fecal incontinence, or infection.59

In another study of HIV-negative patients, there were no recurrences in patients with LSIL diagnosed by high-resolution anoscopy and treated by targeted destruction with electrocautery. In patients with HSIL treated the same way, the recurrence rate was 45%. These patients were retreated with high-resolution anoscopy and targeted destruction.70

Goldstone et al have recently published a study using infrared coagulation, laser, and cautery destruction of HSIL lesions identified by high-resolution anoscopy. The HSIL recurrence rate over a mean follow-up period of 69 months was 62% in HIV-negative MSM and 91% in HIV-positive MSM. A total of 52% of HIV-negative and 82% of HIV-positive MSM developed metachronous lesions. The authors performed close surveillance and repeat treatments as necessary and at the end of the follow-up period, 90% of HIV-negative and 82% of HIV-positive patients were free of HSIL. No patients in the study progressed to anal cancer,71 however, 94% of patients never progress to anal cancer, regardless of treatment, and those that do generally take longer to progress than this study allowed.

Pineda et al described their 10 year experience in treating a large volume of HIV positive patients with HSIL lesions identified by high-resolution anoscopy with infrared coagulation ablation. They performed initial destruction in the operating room followed up by subsequent office based infrared coagulation. At the last follow-up, 78% of patients were free of HSIL lesions. 1.2% of patients progressed to anal cancer over the 10 year period.27

Targeted destruction of lesions identified by high-resolution anoscopy requires close routine follow-up to identify recurrences and metachronous lesions. This approach is able to avoid much of the morbidity and complications associated with wide local excision. That being said, targeted destruction is also associated with procedure-specific morbidity. Chang et al showed that 16 of 29 patients treated this way had uncontrolled pain for a mean of 3 weeks.59 Pineda et al demonstrated that 4% of patients require surgery for bleeding, anal stenosis, or fissure after treatment.27 Park and Palefsky showed significant rates of pain, infection, and bleeding, and patient reported decrease in sexual enjoyment.72 Aside from the morbidity, the associated time and costs to both patients and practitioners should not be discounted.

Surveillance

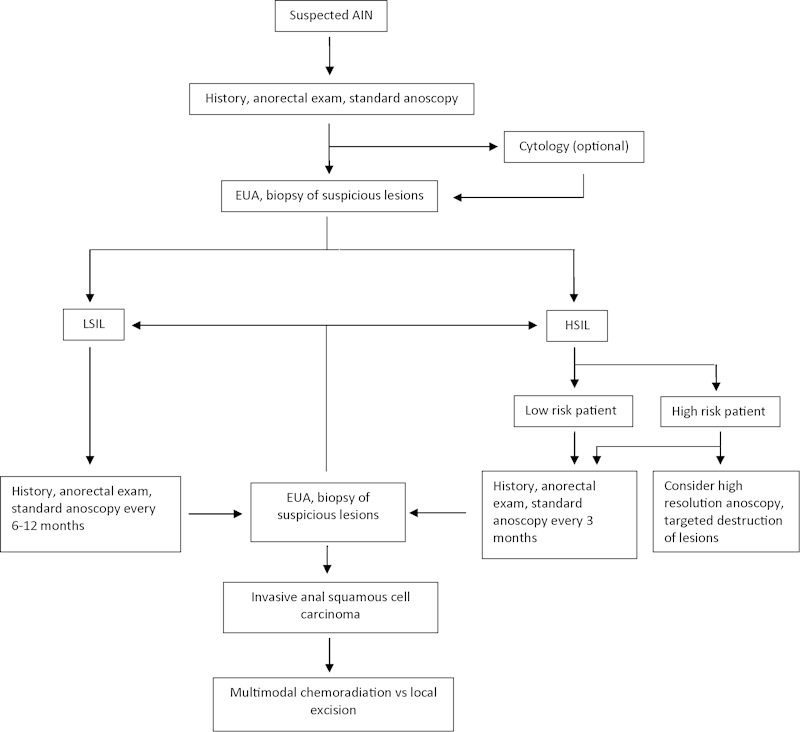

The risk for progression and recurrence of AIN and the need for surveillance have been well established, particularly in high-risk patients. There has been little in the way of prospective or randomized trials to distinguish a specific surveillance regimen that is medically and cost effective. The current recommendation by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is that patients with AIN undergo surveillance with digital rectal exam, standard anoscopy plus or minus high-resolution anoscopy, and application of ascetic acid or Lugol's solution every 3 to 6 months as long as there is still dysplasia present.60 Biopsies should be performed as indicated. If no dysplasia is present, the follow-up period may be lengthened. Special attention should be paid to follow up for high-risk patients, including HIV-positive patients, transplant patients, and MSM, all of which have been shown to have higher rates of persistence and progression.60 A proposed algorithm for the surveillance of AIN is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proposed algorithm for surveillance of AIN.

Summary

With the best available data, we can say that anal cancer develops rarely and slowly, even in high-risk patients. Moreover, when anal cancer does develop, the treatment is very effective with cure rates of 85 to 90%. There is no clear evidence to date that aggressive screening and surveillance can prevent anal cancer, and recurrence and persistence of HSIL remain high regardless of the approach. Many aggressive treatment regimens come with significant morbidity to patients, including infection, bleeding, anal stenosis, and need for colostomy. A policy of careful surveillance for secondary prevention by detecting early invasive cancers and treating with either local excision or multimodal chemoradiotherapy may provide a reasonable balance of morbidity, mortality, and cost.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fenger C, Nielsen V T. Intraepithelial neoplasia in the anal canal. The appearance and relation to genital neoplasia. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand [A] 1986;94(5):343–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1986.tb03003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program SSB Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Available at: www.seer.cancer.gov. Research Data (1973–2012).

- 4.Palefsky J M. Human papillomavirus infection and anogenital neoplasia in human immunodeficiency virus-positive men and women. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1998;23:15–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machalek D A, Poynten M, Jin F. et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):487–500. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darragh T M, Winkler B. Anal cancer and cervical cancer screening: key differences. Cancer Cytopathol. 2011;119(1):5–19. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frisch M, Glimelius B, van den Brule A J. et al. Sexually transmitted infection as a cause of anal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(19):1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711063371904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowen J. Precancerous dermatoses: A study of two cases of chronic atypical epithelial proliferation. J Cutan Dis. 1912;30:241–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vickers P, Jackman R, McDonald J. Anal carcinoma in situ: report of three cases. South Surg. 1939;8:503–507. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turell R. Epidermoid squamous cell cancer of the perianus and anal canal. Surg Clin North Am. 1962;42:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)36788-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oriel J D, Whimster I W. Carcinoma in situ associated with virus-containing anal warts. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84(1):71–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb14199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenger C, Nielsen V T. Dysplastic changes in the anal canal epithelium in minor surgical specimens. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand [A] 1981;89(6):463–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1981.tb00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zbar A P, Fenger C, Efron J, Beer-Gabel M, Wexner S D. The pathology and molecular biology of anal intraepithelial neoplasia: comparisons with cervical and vulvar intraepithelial carcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17(4):203–215. doi: 10.1007/s00384-001-0369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanley M. Chapter 17: Genital human papillomavirus infections—current and prospective therapies. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003:117–124. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter P S, Sheffield J P, Shepherd N. et al. Interobserver variation in the reporting of the histopathological grading of anal intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47(11):1032–1034. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.11.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoler M H, Vichnin M D, Ferenczy A. et al. The accuracy of colposcopic biopsy: analyses from the placebo arm of the Gardasil clinical trials. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(6):1354–1362. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castle P E, Stoler M H, Solomon D, Schiffman M. The relationship of community biopsy-diagnosed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 to the quality control pathology-reviewed diagnoses: an ALTS report. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127(5):805–815. doi: 10.1309/PT3PNC1QL2F4D2VL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darragh T M, Colgan T J, Cox J T. et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the college of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(10):1266–1297. doi: 10.5858/arpa.LGT200570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edge S B, Compton C C. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogunbiyi O A, Scholefield J H, Raftery A T. et al. Prevalence of anal human papillomavirus infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in renal allograft recipients. Br J Surg. 1994;81(3):365–367. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palefsky J M, Holly E A, Hogeboom C J. et al. Virologic, immunologic, and clinical parameters in the incidence and progression of anal squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-positive and HIV-negative homosexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;17(4):314–319. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199804010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman H B, Saah A J, Sherman M E. et al. Human papillomavirus, anal squamous intraepithelial lesions, and human immunodeficiency virus in a cohort of gay men. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(1):45–52. doi: 10.1086/515608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daling J R, Madeleine M M, Johnson L G. et al. Human papillomavirus, smoking, and sexual practices in the etiology of anal cancer. Cancer. 2004;101(2):270–280. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sendagorta E, Herranz P, Guadalajara H. et al. Prevalence of abnormal anal cytology and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions among a cohort of HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(4):475–481. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiels M S, Cole S R, Kirk G D, Poole C. A meta-analysis of the incidence of non-AIDS cancers in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(5):611–622. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b327ca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devaraj B, Cosman B C. Expectant management of anal squamous dysplasia in patients with HIV. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(1):36–40. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0229-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pineda C E Berry J M Jay N Palefsky J M Welton M L High-resolution anoscopy targeted surgical destruction of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: a ten-year experience Dis Colon Rectum 2008516829–835., discussion 835–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Pokomandy A, Rouleau D, Ghattas G. et al. HAART and progression to high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia in men who have sex with men and are infected with HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(9):1174–1181. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chin-Hong P V, Husnik M, Cranston R D. et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection is associated with HIV acquisition in men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2009;23(9):1135–1142. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832b4449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lacey C JN. Therapy for genital human papillomavirus-related disease. J Clin Virol. 2005;32 01:S82–S90. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adami J, Gäbel H, Lindelöf B. et al. Cancer risk following organ transplantation: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(7):1221–1227. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moscicki A B Schiffman M Kjaer S Villa L L Chapter 5: Updating the natural history of HPV and anogenital cancer Vaccine 2006243(Suppl 3):42–51.. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muñoz N, Bosch F X, de Sanjosé S. et al. Risk factors for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III/carcinoma in situ in Spain and Colombia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1993;2(5):423–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoots B E, Palefsky J M, Pimenta J M, Smith J S. Human papillomavirus type distribution in anal cancer and anal intraepithelial lesions. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(10):2375–2383. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gohy L, Gorska I, Rouleau D. et al. Genotyping of human papillomavirus DNA in anal biopsies and anal swabs collected from HIV-seropositive men with anal dysplasia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(1):32–39. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318183a905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson A JM, Smith B B, Whitehead M R, Sykes P H, Frizelle F A. Malignant progression of anal intra-epithelial neoplasia. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(8):715–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lacey H B, Wilson G E, Tilston P. et al. A study of anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV positive homosexual men. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75(3):172–177. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.3.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shvetsov Y B, Hernandez B Y, McDuffie K. et al. Duration and clearance of anal human papilloma infection among women: the Hawaii HPV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):536–546. doi: 10.1086/596758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powles T, Robinson D, Stebbing J. et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and the incidence of non-AIDS-defining cancers in people with HIV infection. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(6):884–890. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walts A E, Lechago J, Bose S. P16 and Ki67 immunostaining is a useful adjunct in the assessment of biopsies for HPV-associated anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(7):795–801. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000208283.14044.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bala R, Pinsky B A, Beck A H, Kong C S, Welton M L, Longacre T A. p16 is superior to ProEx C in identifying high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) of the anal canal. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(5):659–668. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31828706c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pirog E C, Quint K D, Yantiss R K. P16/CDKN2A and Ki-67 enhance the detection of anal intraepithelial neoplasia and condyloma and correlate with human papillomavirus detection by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(10):1449–1455. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f0f52a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cranston R D, Darragh T M, Holly E A. et al. Self-collected versus clinician-collected anal cytology specimens to diagnose anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-positive men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(4):915–920. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R. et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2114–2119. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chin-Hong P V, Berry J M, Cheng S C. et al. Comparison of patient- and clinician-collected anal cytology samples to screen for human papillomavirus-associated anal intraepithelial neoplasia in men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):300–306. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mathews W C, Sitapati A, Caperna J C, Barber R E, Tugend A, Go U. Measurement characteristics of anal cytology, histopathology, and high-resolution anoscopic visual impression in an anal dysplasia screening program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(5):1610–1615. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200412150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Betancourt E M, Wahbah M M, Been L C, Chiao E Y, Citron D R, Laucirica R. Anal cytology as a predictor of anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-positive men and women. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41(8):697–702. doi: 10.1002/dc.22941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Panther L A, Wagner K, Proper J. et al. High resolution anoscopy findings for men who have sex with men: inaccuracy of anal cytology as a predictor of histologic high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia and the impact of HIV serostatus. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(10):1490–1492. doi: 10.1086/383574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nahas C SR, da Silva Filho E V, Segurado A AC. et al. Screening anal dysplasia in HIV-infected patients: is there an agreement between anal pap smear and high-resolution anoscopy-guided biopsy? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(11):1854–1860. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b98f36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weis S E, Vecino I, Pogoda J M. et al. Prevalence of anal intraepithelial neoplasia defined by anal cytology screening and high-resolution anoscopy in a primary care population of HIV-infected men and women. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(4):433–441. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318207039a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berry J M, Palefsky J M, Jay N, Cheng S C, Darragh T M, Chin-Hong P V. Performance characteristics of anal cytology and human papillomavirus testing in patients with high-resolution anoscopy-guided biopsy of high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(2):239–247. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819793d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Connor J J. The study of anorectal disease by colposcopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1977;20(7):570–572. doi: 10.1007/BF02586620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tramujas da Costa e Silva I, de Lima Ferreira L C, Santos Gimenez F. et al. High-resolution anoscopy in the diagnosis of anal cancer precursor lesions in renal graft recipients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(5):1470–1475. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9750-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jay N, Berry J M, Hogeboom C J, Holly E A, Darragh T M, Palefsky J M. Colposcopic appearance of anal squamous intraepithelial lesions: relationship to histopathology. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(8):919–928. doi: 10.1007/BF02051199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pineda C E, Berry J M, Welton M L. High resolution anoscopy and targeted treatment of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(1):126. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chung A P, Rosenfeld D B. Intraoperative high-resolution anoscopy: a minimally invasive approach in the treatment of patients with Bowen's disease and results in a private practice setting. Am Surg. 2007;73(12):1279–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abbasakoor F, Boulos P B. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Surg. 2005;92(3):277–290. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jay N, Berry J M, Hogeboom C J, Holly E A, Darragh T M, Palefsky J M. Colposcopic appearance of anal squamous intraepithelial lesions: relationship to histopathology. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(8):919–928. doi: 10.1007/BF02051199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang G J, Berry J M, Jay N, Palefsky J M, Welton M L. Surgical treatment of high-grade anal squamous intraepithelial lesions: a prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(4):453–458. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steele S R Varma M G Melton G B Ross H M Rafferty J F Buie W D; Standards Practice Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Practice parameters for anal squamous neoplasms Dis Colon Rectum 2012557735–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crawshaw B P, Russ A J, Stein S L. et al. High-resolution anoscopy or expectant management for anal intraepithelial neoplasia for the prevention of anal cancer: is there really a difference? Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(1):53–59. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mahto M, Nathan M, O'Mahony C. More than a decade on: review of the use of imiquimod in lower anogenital intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21(1):8–16. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richel O, Wieland U, de Vries H JC. et al. Topical 5-fluorouracil treatment of anal intraepithelial neoplasia in human immunodeficiency virus-positive men. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(6):1301–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Franceschi S, De Vuyst H. Human papillomavirus vaccines and anal carcinoma. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(1):57–63. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32831b9c81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Palefsky J M, Giuliano A R, Goldstone S. et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(17):1576–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Strauss R J, Fazio V W. Bowen's disease of the anal and perianal area. A report and analysis of twelve cases. Am J Surg. 1979;137(2):231–234. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(79)90152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Margenthaler J A Dietz D W Mutch M G Birnbaum E H Kodner I J Fleshman J W Outcomes, risk of other malignancies, and need for formal mapping procedures in patients with perianal Bowen's disease Dis Colon Rectum 200447101655–1660., discussion 1660–1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reynolds V H, Madden J J, Franklin J D, Burnett L S, Jones H W III, Lynch J B. Preservation of anal function after total excision of the anal mucosa for Bowen's disease. Ann Surg. 1984;199(5):563–568. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198405000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marchesa P, Fazio V W, Oliart S, Goldblum J R, Lavery I C. Perianal Bowen's disease: a clinicopathologic study of 47 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(11):1286–1293. doi: 10.1007/BF02050810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pineda C E Berry J M Jay N Palefsky J M Welton M L High resolution anoscopy in the planned staged treatment of anal squamous intraepithelial lesions in HIV-negative patients J Gastrointest Surg 200711111410–1415., discussion 1415–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goldstone R N, Goldstone A B, Russ J, Goldstone S E. Long-term follow-up of infrared coagulator ablation of anal high-grade dysplasia in men who have sex with men. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(10):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318227833e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Park I U, Palefsky J M. Evaluation and management of anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-negative and HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(2):126–133. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0090-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]