Abstract

Conducting Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) research with Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) is difficult due to low participation rates and high attrition. Forty-seven AYAs with newly diagnosed cancer at two large hospitals were prospectively surveyed at the time of diagnosis, 3–6 and 12–18 months later. A subset participated in 1:1 semi-structured interviews. Attrition prompted early study-closure at one site. The majority of patients preferred paper-pencil to online surveys. Interview-participants were more likely to complete surveys (e.g., 93% vs. 58% completion of 3–6 month surveys, p=0.02). Engaging patients through qualitative methodologies and using patient-preferred instruments may optimize future research success.

Keywords: Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology (AYA), Patient-reported outcomes, pediatric cancer, health-services research

INTRODUCTION

Improving health and psychosocial outcomes for Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) with cancer has been difficult because their participation in clinical and Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) research has been lacking.[1,2] For example, despite extensive efforts (e.g., multiple mailings, telephone calls, and monetary incentives) fewer than half of eligible AYAs responded to survey requests on the AYA Health Outcomes and Patient Experience (AYA HOPE) study or a similar population-based Group Health analysis.[3,4] Additionally, the bulk of PROs studies among AYA oncology patients have been conducted during the survivorship phase of the illness; few describe PROs during cancer-therapy, despite evidence that AYAs experience high distress and poor quality of life during this time-frame.[5–8]

In order to inform future, successful collection of AYA PROs data, we aimed to assess the feasibility of prospective, longitudinal assessments of PROs amongst AYAs with newly diagnosed cancer. Exploratory aims were to determine if qualitative methods to promote patient-engagement would enable retention.

METHODS

Participants

The “Resilience in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer” study was a prospective, longitudinal, mixed-methods study conducted at Seattle Children’s Hospital (SCH) and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children’s Hospital (DF/BCH). It was approved by the Institutional Review Board at both sites. Consecutive AYAs (ages 14–25 years) diagnosed with primary cancer between December/2012 and November/2013 (SCH) or Feb/2014 and Jan/2015 (DF/BCH) were eligible if they were: English-speaking, able to complete written surveys, and diagnosed with non Central-Nervous System (CNS) cancer requiring chemotherapy treatment between 14 and 60 days prior to enrollment. As part of a qualitative aim of the study, the first 18 patients enrolled at SCH were invited to participate in 1:1 semi-structured interviews and complete PROs surveys one week following enrollment (T1), 3–6 months (T2), and 12–18 months later (T3). All subsequent participants were invited only to complete PROs at the same time-points. Participants received $50 for each interview and $25 for each survey. Those who developed refractory or relapsed disease during the study were removed in order to minimize heterogeneity of experiences.

Assessments

We have previously described our qualitative interview guide and the survey.[9,10] Briefly, interviews focused on patient-perceptions of stress, coping, and resilience. All participants were offered the survey online (via tablet-computer) or via paper-and-pencil at each time-point. Electronic reminders for incomplete surveys were sent 7- and 10-days after each due-date, and surveys were collected for up to 3 months later before being considered lost to follow-up. Due to funding constraints and attrition, we removed the T3 survey option for DF/BCH mid-study.

Analyses

We calculated the proportion of: (a) enrolled-to-approached; and (b) survey-eligible to survey-completed participants at each time-point. Exploratory analyses used chi-Square tests to assess differences in: (a) enrollment-rate by site; (b) survey-completion by site; and, (c) survey-completion by study arm (interview + survey vs. survey only).

RESULTS

Enrollment

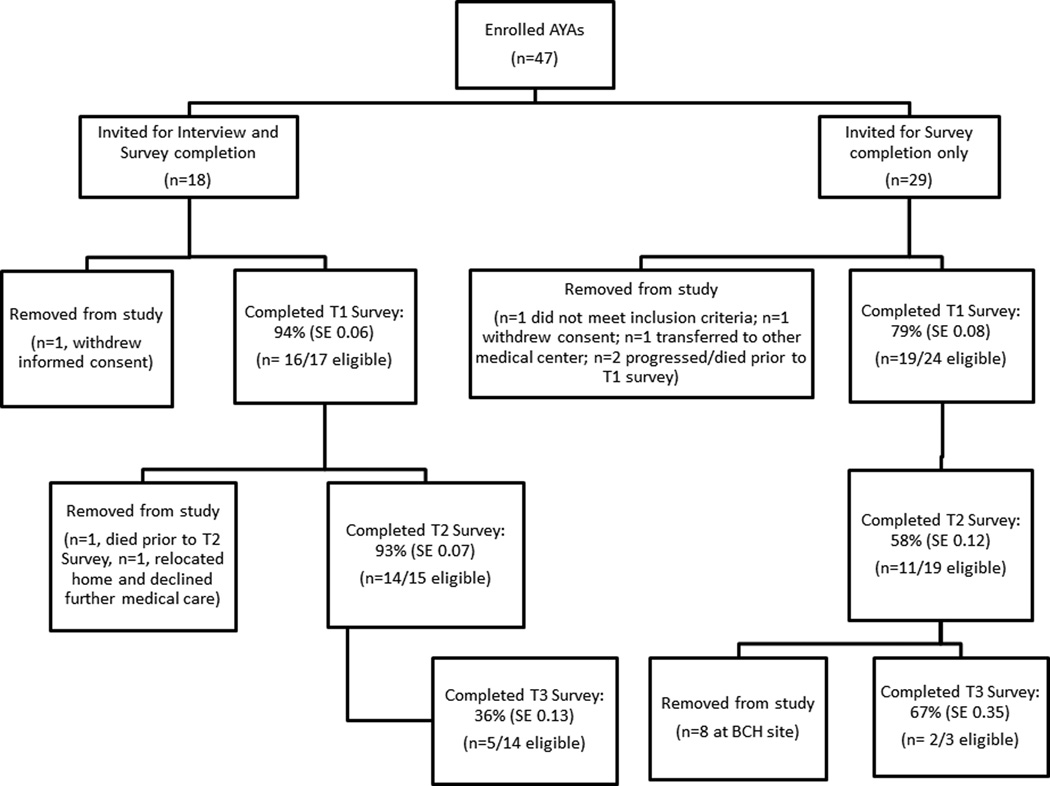

Fifty-two of 57 eligible patients were approached across both sites. Reasons for non-approach were: n=2 on competing study, n=3 primary provider declined permission. Forty-seven (90%) of the 52 patients enrolled (29/31 [94%] at SCH, 18/21 [86%] at DF/BCH; chi-square=0.88, p=0.35); however, 6 were removed prior to T1 (Figure 1). Enrollment was similar on each arm of the study (18/20 [90%] on interview+survey arm, 29/32 [90%] on survey-only arm, chi-square=0.005, p=0.94).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient assignment and corresponding survey completion. Legend: AYAs: Adolescents and Young Adults; T1: Survey at time-point 1 (enrollment); T2: Survey at time-point 2 (3–6 months post-enrollment); T3: Survey at time-point 3 (12–18 months post-enrollment); SE: Standard Error; DF/BCH: Dana Farber/Boston Children’s Hospital

Patient characteristics and preferences

Thirty-five (74% of enrolled) completed the first survey (Table I). Their mean age was 17.6 years (Standard Deviation, SD, 2.3), 20 (57%) were male, and almost all were non-Hispanic white. Twenty (80%), 15 (60%), and 7 (88%) of returned surveys were paper-versions at T1, T2, and T3, respectively.

Table I.

Participant Characteristics (N=35 who completed survey at time of enrollment)

| Study Arm | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Interview + Survey (n=16) |

Survey Only (n=19) |

Total (n=35) |

|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 17.8 (2.9) | 17.4 (1.8) | 17.6 (2.3) |

| Sex | N (%)* | N (%)* | N (%)* |

| Male | 7 (44) | 13 (68) | 20 (57) |

| Female | 9 (56) | 6 (32) | 15 (43) |

| Cancer-type | |||

| Sarcoma | 7 (44) | 6 (32) | 13 (37) |

| ALL | 4 (25) | 4 (21) | 8 (23) |

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 2 (13) | 3 (16) | 5 (14) |

| AML | 2 (13) | 2 (11) | 4 (9) |

| NHL | 1 (6) | 2 (11) | 3 (14) |

| Germ Cell Tumor | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (3) |

| Other | 0 | 1(5) | 1 (3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 15 (94) | 16 (84) | 31 (89) |

| Hispanic White | 1 (6) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| African American | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (3) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (3) |

Legend: SD: Standard Deviation; ALL: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia; AML: Acute Myelogenous Leukemia; NHL: Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma.

Percents may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Survey-completion

Twenty-three (96%) of 24 SCH participants (interview+survey and survey-only arms) and 12/17 (71%) DF/BCH participants (survey-only arm) completed T1 surveys (chi-square=5.07, p=0.02). At T2, survey completion rates were 17/22 (77%) and 8/12 (67%), respectively (chi-square=0.45, p=0.5). There were no detectable differences in survey-completion by site when analyses were limited to survey-only participants (T1: 7/7 at SCH vs. 12/17 at DF/BCH, chi-square=2.6, p=0.11; T2: 3/7 at SCH and 8/12 at DF/BCH. chi-square=1.0, p=0.31).

With respect to survey-arm, 16/17 (94%) of the interviewed patients returned their T1 surveys compared to 19/25 (76%) of survey-only patients (chi-square=2.4, p=0.12). At T2, completion rates were 14/15 (93%) and 11/19 (58%), respectively (chi-square=5.4, p=0.02).

DISCUSSION

Differences in AYA patient-engagement may impact participation and retention. Almost all of the patients who completed 1:1 interviews also completed their surveys at the time of enrollment (T1) and at 3–6 months later (T2). In comparison, survey non-completion and attrition were significant on the survey-only arm.

A potential explanation is that interviewed AYAs experienced a more tangible sign that their opinions were valued. Having a dedicated interview-appointment and additional monetary incentive may also have provided an opportunity and/or a sense of obligation to complete the survey. Alternatively, survey-completion was defined by study site; patients at SCH may have felt more invested simply because the interview-arm was offered there. We were unable to detect differences in survey-completion by site when we limited analyses only to those on the same survey-only arm; however, our numbers were too small to confidently conclude site was not a factor. Regardless, our results suggest that active, and perhaps more personal, inclusion of AYA voices may facilitate research success.

In some ways, our findings are surprising. Described barriers to PROs collection are time-commitment and perceived burden.[11,12] These are particularly relevant for AYAs who are also struggling with the demands and implications of their diagnosis.[7,8] In our sample, the added interview-time did not prohibit participation. Likewise, the majority of AYAs chose to complete their surveys on paper rather than electronically. Others also have found similar results; 76% of respondents on the AYA HOPE study selected paper rather than online options.[3]

These findings have implications for future research. Electronic PROs may facilitate data analysis; however, patient preferences are an additional factor in study success. Likewise, multiple mailings and phone calls to retain patients in longitudinal survey-based studies can be expensive and cumbersome; in-person contact may be an inexpensive and simple alternative.[4]

There are several notable limitations to this study. First, our small sample size restricted the power to explore other potential factors of survey-completion such as sex or cancer-type; the higher proportion of male patients on the survey-only arm may have introduced bias. Furthermore, we did not anticipate such attrition in the survey-only arm. The subsequent decrease in sample size, paired with the early study-closure at DF/BCH meant we could not determine if differences would have endured (or changed) over longer periods of time.

Second, our sample lacked diversity, in part because our instruments required written/spoken English. We were unable to assess cultural or racial differences in participation, although prior evidence suggests minority AYAs are less likely to respond to survey-based research.[3] We also excluded patients with CNS tumors in order to limit the heterogeneity of patient-experiences. Nevertheless, AYAs with CNS tumors represent an important population at high risk for poor outcomes.[7,13]

AYA patient participation in clinical research, including PROs studies, is imperative in order to improve health and psychosocial outcomes. This feasibility study suggests that active patient-engagement with qualitative methods may encourage sustained data collection and ultimate study success.

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

We would like to thank Madeleine Bilodeau, BS, and Victoria Klein, BS, for their help with recruitment and data management of this study. We are grateful to the patients and families who participated in the project. This research was funded by a St. Baldrick’s Fellow award, a Young Investigator award from CureSearch for Children’s Cancer, a Clinical Research Scholar Award from Seattle Children’s Hospital’s Center for Clinical and Translational Research, and the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number KL2TR000421. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AYA

Adolescent and Young Adult

- PROs

Patient-reported outcomes

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No competing financial interests exits.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parsons HM, Harlan LC, Seibel NL, Stevens JL, Keegan TH. Clinical trial participation and time to treatment among adolescents and young adults with cancer: does age at diagnosis or insurance make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(30):4045–4053. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari A, Montello M, Budd T, Bleyer A. The challenges of clinical trials for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(5 Suppl):1101–1104. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harlan LC, Lynch CF, Keegan TH, Hamilton AS, Wu XC, Kato I, West MM, Cress RD, Schwartz SM, Smith AW, Deapen D, Stringer SM, Potosky AL Group AHSC. Recruitment and follow-up of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: the AYA HOPE Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(3):305–314. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0173-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards J, Wiese C, Katon W, Rockhill C, McCarty C, Grossman D, McCauley E, Richardson LP. Surveying adolescents enrolled in a regional health care delivery organization: mail and phone follow-up--what works at what cost? J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(4):534–541. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.04.100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwak M, Zebrack BJ, Meeske KA, Embry L, Aguilar C, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, Li Y, Butler M, Cole S. Trajectories of psychological distress in adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: a 1-year longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(17):2160–2166. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan TH, Zebrack B, Chen VW, Neale AV, Hamilton AS, Shnorhavorian M, Lynch CF. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in the United States: the Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(17):2136–2145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landolt MA, Vollrath M, Niggli FK, Gnehm HE, Sennhauser FH. Health-related quality of life in children with newly diagnosed cancer: a one year follow-up study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hedstrom M, Ljungman G, von Essen L. Perceptions of distress among adolescents recently diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27(1):15–22. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000151803.72219.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg AR, Yi-Frazier JP, Wharton C, Gordon K, Jones B. Contributors and Inhibitors of Resilience Among Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2014;3(4):185–193. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2014.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenberg AR, Wolfe J, Bradford MC, Shaffer ML, Yi-Frazier JP, Curtis JR, Syrjala KL, Baker KS. Resilience and psychosocial outcomes in parents of children with cancer. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2014;61(3):552–557. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mularski RA, Rosenfeld K, Coons SJ, Dueck A, Cella D, Feuer DJ, Lipscomb J, Karpeh MS, Jr, Mosich T, Sloan JA, Krouse RS. Measuring outcomes in randomized prospective trials in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1 Suppl):S7–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston DL, Nagarajan R, Caparas M, Schulte F, Cullen P, Aplenc R, Sung L. Reasons for non-completion of health related quality of life evaluations in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macartney G, Harrison MB, VanDenKerkhof E, Stacey D, McCarthy P. Quality of life and symptoms in pediatric brain tumor survivors: a systematic review. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2014;31(2):65–77. doi: 10.1177/1043454213520191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]