Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the prevalence of central precocious puberty (CPP) after treatment for tumors and malignancies involving the central nervous system (CNS) and examine repercussions on growth and pubertal outcomes.

Design

Retrospective study of patients with tumors near and/or exposed to radiotherapy to the hypothalamus/pituitary (HPA).

Patients and Measurements

Patients with CPP were evaluated at puberty onset, completion of GnRH agonist treatment (GnRHa), and last follow-up. Multivariable analysis was used to test associations between tumor location, sex, age at CPP, GnRHa duration and a diagnosis of CPP with final height <-2SD score (SDS), gonadotropin deficiency (LH/FSHD) and obesity, respectively.

Results

Eighty patients (47 females) had CPP and were followed for 11.4±5.0 years (mean ± SD). The prevalence of CPP was 15.2% overall, 29.2% following HPA tumors and 6.6% after radiotherapy for non-HPA tumors. Height <-2SDS was more common at the last follow-up than at puberty onset (21.4% vs. 2.4%, p=0.005). Obesity was more prevalent at the last follow-up than at completion of GnRHa or puberty onset (37.7%, 22.6% and 20.8% respectively, p=0.03). Longer duration of GnRHa was associated with increased odds of final height <-2SDS (OR=2.1, 95% CI 1.0–4.3); longer follow-up with obesity (OR=1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.6). LH/FSHD was diagnosed in 32.6%. There was no independent association between CPP and final height <- 2SDS, LH/FSHD and obesity in the subset of patients with HPA low-grade gliomas.

Conclusions

Patients with organic CPP experience an incomplete recovery of growth and a high prevalence of LH/FSHD and obesity. Early diagnosis and treatment of CPP may limit further deterioration of final height prospects.

Keywords: Puberty, precocious, Primary brain neoplasms

Introduction

Neoplasms within or near the hypothalamus/pituitary axis (HPA) 1–3 and cranial radiotherapy (CRT) (18 to 50 Gy) are known risk factors for central precocious puberty (CPP) 4–8. When CPP occurs in the context of a central nervous system (CNS) insult, it is referred to as organic 2–8. In other instances, CPP is referred to as idiopathic 2;9–11. Prevalence and long-term outcomes in terms of height 12–14, reproductive health and obesity 14–16 have been reported in patients with a history of idiopathic CPP, while those with organic CPP generally have been excluded from these analyses. A recent report of a high prevalence of CPP (26.0%) among children with optic glioma highlights the importance of further investigating the prevalence of this endocrinopathy among all patients at-risk and obtaining a better understanding of its potential long-term consequences on overall health 3. The aims of the current study were to estimate the prevalence of organic CPP, describe the long-term health outcomes of patients diagnosed with this condition and provide an assessment of the specific impact of CPP on these outcomes in a large cohort of well characterized patients with childhood CNS lesions and/or exposed to CRT.

Materials and Methods

Patients

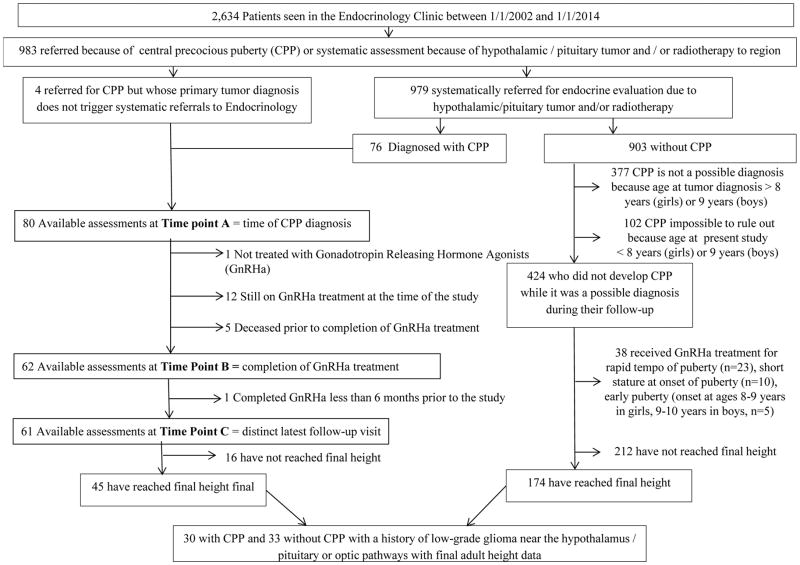

The present study was approved by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) institutional review board. The electronic medical records (EMR) of all patients (n=2,634) assessed between January 1, 2002 (date of initiation of EMR use at SJCRH) and December 31, 2013 in the endocrinology clinic were used to identify 983 patients referred because of CPP or for systematic assessment as they were at high risk of hypothalamic/pituitary dysfunction including CPP (Figure 1). A total of 80 patients with CPP were identified; the remaining 903 had been referred to endocrinology for systematic assessments but did not have a diagnosis of CPP (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram

Methods

The diagnosis of CPP

CPP was defined as the onset of puberty before the age of eight years in girls and nine years in boys as a result of the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary gonadal axis. The diagnosis of puberty was based on the presence of breast development in girls and by the observation of a testicular size ≥ 4 mL in boys; secondary sexual characters and plasma testosterone levels were used in boys whose treatment exposures potentially affected testicular volume 13. Central origin of precocious puberty was confirmed by plasma levels of LH ≥5 IU/L 40–180 minutes after the subcutaneous administration of either GnRH (100 micrograms, n= 35) or a GnRH agonist (GnRHa), leuprolide acetate (20 micrograms/kg, n=23) or by the observation of baseline pubertal levels of sex steroids associated with non-suppressed LH (≥0.3 IU/L) (n=22) 17. Patients presenting with paraneoplastic precocious puberty at the time of tumor diagnosis as documented by increased plasma levels of human chorionic gonadotropin were not included in the study. In girls with discrepant clinical and laboratory data, confirmation of gonadal and uterine stimulation was sought using pelvic ultrasound 18. All CNS tumor diagnoses relied on the use of magnetic resonance imaging and confirmation via biopsy or post-surgical pathology as indicated.

Data Collection (Figure 1)

Data on patients with CPP were retrospectively abstracted from three time points: onset of puberty, completion of GnRHa treatment when applicable, and at last follow-up. An interval of at least six months between completion of GnRHa treatment and last follow-up was required for the evaluations to be considered distinct (Figure 1). Height was measured using a Harpenden stadiometer and expressed in standard deviations (SD) score (SDS) from the mean of a normative population using chronological age- and sex-specific values 19, 20. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formula: weight in kg/(height in m)2 and expressed in SDS in relation to chronological age and sex. In order to assess the impact of tumor location, patients were divided into 2 groups (Table 1). Patients in Group 1 (n=57, 71.3%) had HPA tumors; those in Group 2 (n=23, 28.7%) had tumors in other areas of the brain (n=21) or did not have a CNS tumor diagnosis (acute lymphoblastic leukemia, n=1; acute myeloblastic leukemia, n=1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patients with CPP (N=80) | CPP following HPA low-grade glioma* (N=30) | HPA low-grade glioma without CPP* (N=33) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic N (%); mean± SD | |||

| Sex | |||

| Females | 47 (58.8%) | 13 (43.3%) | 17 (51.5%) |

| Males | 33 (41.2%) | 17 (56.7%) | 16 (48.5%) |

| Age at study, years | 18.4 ± 6.5 | 24.5 ± 4.2 | 22.7 ± 3.8 |

| Age at tumor / cancer diagnosis, years | 3.6 ± 2.6 a | 4.1±3.0 | 5.3 ± 2.4 |

| Tumor / cancer diagnosis: | |||

| Glioma | 51 (63.8%) b | 30 (100%) d | 33 (100%) e |

| Craniopharyngioma | 7 (8.7%) | N/A | N/A |

| Medulloblastoma | 6 (7.5%) | N/A | N/A |

| Ependymoma | 5 (6.3%) | N/A | N/A |

| Choroid plexus carcinoma | 2 (2.5%) | N/A | N/A |

| Primary neuro-ectodermal tumor | 2 (2.5%) | N/A | N/A |

| Others | 7 (8.7%) c | N/A | N/A |

| Tumor / cancer location | |||

| Group 1 | |||

| Optic pathways | 23 (28.8%) | 16 (53.3%) | 12 (36.4%) |

| Hypothalamus | 18 (22.5%) | 10 (33.3%) | 11 (33.3%) |

| Sellar / supra-sellar | 8 (10 %) | 1 (0.03%) | 1 (0.03%) |

| Thalamus | 8 (10%) | 3 (0.1%) | 9 (27.3%) |

| Group 2 | |||

| Posterior fossa | 8 (10%) | N/A | N/A |

| Other, within central nervous system | 13 (16.3%) | N/A | N/A |

| Other, non-central nervous system | 2 (2.5%) | N/A | N/A |

| Cranial radiotherapy (n, %), Dose (mean± SD, Gy) | 69 (86.3%), 55.2 ± 14.4 | 27 (90.0%) 53.4 ± 1.6 |

19 (57.6%) f 52.0 ± 7.6 |

| Spinal radiotherapy (n, %) Dose (mean± SD, Gy) |

11 (13.7%) 30.6 ± 6.6 |

2 (6.6%) 36 ± 0.0 |

1 (3.0%) N/A |

| Chemotherapy | 59 (73.8%) | 21 (70%) | 12 (36.4%) |

| Age at CPP– males, years | 7.4 ± 2.0 | 7.1 ± 2.1 | N/A |

| Age at CPP – females, years | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 6.8 ± 1.2 | N/A |

| Tanner stage at diagnosis of CPP | |||

| Stage2 | 69 (86.3%) | 23 (76.7%) | N/A |

| Stage 3 | 10 (12.5%) | 6 (20%) | N/A |

| Stage 4 | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (3.3%) | N/A |

| Time interval between tumor/cancer diagnosis and CPP, years | 3.5 ± 2.4 | 2.8 ± 2.4 | N/A |

| GnRHa treatment complete (n, %) Duration of GnRHa treatment (mean± SD, years) |

68 (85%), 4.2 ± 1.8 | 29 (97%) g 4.7± 2.3 |

N/A |

| Duration of follow-up since CPP, years | 11.4 ± 5.0 | 13.9±4.3 | N/A |

CPP= Central precocious puberty, HPA= Hypothalamic / pituitary area tumors, GnRHa= Pubertal suppression using GnRH agonist.

with available final height data

excludes deceased subjects (n=6).

includes low grade astrocytoma (n=26), Ganglioglioma (n=3) and glioblastoma (n=2); n=13 of these patients had type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF-1).

1 patient per each of the following diagnoses: ganglioneuroma, germinoma, pineoblastoma, retinoblastoma with brain metastases, Wilms tumor with brain metastases, acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute myeloblastic leukemia.

8 patients had NF-1

8 patients had NF-1

includes 1 patient treated with 22 Gy via gamma-knife (excluded from mean dose calculation)

1 patient was not treated with GnRHa following spontaneous regression of pubertal symptoms while receiving chemotherapy

In order to assess the impact of CPP on study outcomes, controls were sought among similar patients on whom final height data were available but who did not develop CPP and were never treated with a GnRHa. The patients who were identified through this process (n=174) were significantly different from those with CPP who had attained final height (n=45) in terms of age distribution, tumor types, tumor locations and type of CRT (Appendix Table A1). Comparisons were therefore limited to patients with HPA low grade gliomas (n=33) as they had the highest representation among patients with CPP (n=30) (Table 1).

Appendix Table A1.

Comparison between patients with and without CPP for whom final adult height data were available

| Patients with CPP (n=45) N (%) |

Patients without CPP (n=174) N (%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at tumor diagnosis | |||

| <5 years | 29 (64.4) | 84 (48.3) | 0.05 |

| ≥ 5 years | 16 (35.6) | 90 (51.7) | |

| Etiology | |||

| Low-grade glioma | 30 (66.7)* | 46 (26.4)* | <0.0001 |

| High-grade glioma | 1 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Craniopharyngioma | 3 (6.7) | 25 (14.4) | |

| Medulloblastoma | 8 (8.9) | 54 (31.0) | |

| Ependymoma | 2 (4.4) | 41 (23.6) | |

| Other | 5 (11.1) | 6 (3.5) | |

| Group | |||

| 1 | 35 (77.8) | 59 (33.9) | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 10 (22.2) | 115 (66.1) | |

| Type of radiotherapy | |||

| None | 4 (8.9) | 15 (8.6) | 0.01 |

| Cranial alone | 35 (77.8) | 95 (54.6) | |

| Cranio-spinal | 6 (13.3) | 64 (36.8) | |

CPP= central precocious puberty. Group 1= Tumors located in the hypothalamus, thalamus, optic pathways, sellar or supra-sellar regions Group 2= Tumors / cancers affecting other locations.

all 30 patients with CPP and 33 patients without CPP belonged to Group 1.

Study Outcomes

Height was assessed by comparing height SDS and the prevalence of short stature, defined as height <-2SDS, at the three study time points. Skeletal maturation was assessed using X-rays of the left hand and wrist to determine bone age 21 and to calculate predicted final height 22. Final height was defined as growth velocity in the prior year of <2 cm or radiologic evidence of complete skeletal maturation (i.e., bone age ≥14 years in girls or ≥15 years in boys). Target (mid-parental) height was calculated using the formula: [mother’s height (cm) + father’s height (cm)] /2 − 6.5 cm in girls or + 6.5 cm in boys 23. Pubertal outcomes were studied by assessing the resumption of puberty after the discontinuation of GnRHa, of subsequent development of LH/FSH deficiency (LH/FSHD) in patients ≥14 years old (Table 1) and the presence of abnormal uterine bleeding over a period >6 months among patients ≥16 years old 24. Obesity was defined as a BMI >2SDS in individuals <20 years old or an absolute BMI >30 kg/m2 in those ≥20 years old.

Laboratory Measures and Assessment of Endocrine Dysfunctions

Plasma levels of LH, FSH, estradiol, testosterone, GH, Free T4, TSH and cortisol were measured using standard commercial immunoassays available during the study period. Dynamic testing for GH deficiency (GHD) was performed in all patients with linear growth deceleration over a period ≥6 months or because of participation in a prospective study on CRT effects (n=16; 13 in Group 1, three in Group 2) 25. The diagnostic criteria for endocrinopathies are summarized in Appendix Table A2.

Appendix Table A2.

Diagnostic Criteria for Associated Endocrinopathies

| Endocrinopathy | Diagnostic Modality | Diagnostic Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| GHD | Dynamic testing using arginine-LDOPA, arginine- insulin or glucagon. | GH peak < 10 μg/L (10 ng/mL) |

| TSHD | Plasma FT4 and TSH | FT4< 11.6 nmol/L (0.9 ng/dL) with TSH<4.0 mIU/L |

| ACTHD | Screening with 8 AM plasma cortisol. Confirmation using low-dose ACTH test. | 8 AM cortisol < 276 nmol/L (10 μg/dL) and Stimulated cortisol level < 442 nmol/L (16 μg/dL). |

| LH/FSHD | Plasma LH, FSH, estradiol (females) or testosterone (males) and correlation to clinical assessment. | Ages 14–18 years: Delayed or arrested puberty with low estradiol (females) or testosterone (males) and without elevations in LH or FSH according to Tanner stage normative values. |

| Age ≥18 years, amenorrhea with estradiol levels < 62.4 pmol/L (1.7 ng/dL) (females) or testosterone levels < 6.940 nmol/L (200 ng/dL) (males) without elevations in LH (< 7 IU/ L in males) or FSH (< 11.2 IU/L in females and < 9.2 IU/L in males). | ||

| Primary Hypothyroidism | Plasma FT4 and TSH | TSH> 4.5 mIU/L. |

Statistics

Data were expressed as means ± SD. The Wilcoxon signed rank was used to compare auxological parameters at the three time points and rank sum test between Groups 1 and 2. The McNemar test was used to compare the prevalence of short stature and obesity and Fisher’s exact test for tumor location. In patients with CPP, the effects of tumor location (Group 1 or 2), sex, age at CPP, exposure to cranio-spinal radiotherapy (CSI), duration of GnRHa treatment and duration of follow-up since the diagnosis of CPP on final height <-2 SDS, obesity and LH/FSHD were tested in univariable models using Chi-Square or Fisher Exact tests. In patients with HPA low-grade glioma (with or without CPP), the effects of CPP, GHD, type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF-1), chronological age at tumor diagnosis (<5 years vs. ≥5 years), and type of CRT (none, vs. CRT alone vs. CSI) on final height <-2SD, obesity and LH/FSHD were tested in univariable models using Chi-Square or exact Chi-Square tests. Variables with p-values ≤0.1 from the univariable analyses were included in multivariable logistic regression models to determine independent associations with outcome measures.

Results

Patient and treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1. CPP was present before or at the time of tumor/cancer diagnosis in four patients (5%), it appeared after the diagnosis of the primary tumor/cancer but prior to CRT in 14 (17.5%) and after CRT in 48 (60%). The remaining 14 patients (17.5%) were diagnosed with CPP subsequent to a diagnosis of a CNS lesion and had no history of exposure to CRT. Hydrocephalus was present in 47.5% of patients. There were no patients with cystic malformations or hydrocephalus in the absence of a tumor, and none had a diagnosis of hamartoma.

Seventy-nine of the 80 patients were treated with various GnRHa preparations including intramuscular monthly injections of depot leuprolide (n=71), subcutaneous yearly implants of histrelin (n= 14) and/or intranasal nafarelin (n=1); 7 patients treated initially with depot leuprolide were subsequently switched to histrelin at various points of their follow-up. A total of 12 patients were still receiving GnRHa at the time of their last evaluation. Endocrine disturbances diagnosed during follow-up included GHD (n=53, 66%), TSH deficiency (n=28, 35%), LH/FSHD (n=15, prevalence 32.6% among patients ≥14 years of age), ACTH deficiency (n= 15, 19%), central diabetes insipidus (n=5, 6%), and primary hypothyroidism (n=5, 6%).

GHD was diagnosed a mean of 2.3 years after the diagnosis of CPP in Group 1 and 1.7 years before CPP in Group 2 (Table 2). Among patients with GHD, 34% were never treated with GH or received it for less than 1 year. In the 25 patients who completed GH replacement therapy, treatment was started at 9.1±2.1 years of age with a mean duration of 5.6±2.5 years.

Table 2.

Comparisons according to Tumor / Cancer Location

| Group 1 | Group 2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 57 | 23 | |

| Male (N, %) | 24 (42.1%) | 9 (39.1%) | 0.81 |

| Female (N, %) | 33 (57.1%) | 14 (60.8%) | |

| Age at tumor / cancer diagnosis, years | 3.8±2.8 | 3.2±2.0 | 0.59 |

| Hydrocephalus at tumor presentation | 27 (47.4%) | 11 (47.8%) | 1.0 |

| Age at time point A (Male), years | 7.1±2.0 | 8.2±1.8 | 0.07 |

| Age at time point A (Female), years | 6.6±1.1 | 7.5±0.9 | 0.01 |

| Patients with GHD (N, %) | 40 (70.2%) | 12 (52.2%) | 0.14 |

| Patients with GHD, never treated (%) | 30% | 25% | 0.72 |

| Age at GHD diagnosis, years | 9.0±2.4 | 6.3±2.0 | 0.001 |

| Age at starting GH replacement, years | 9.6±2.1 | 7.6±1.4 | 0.02 |

| Time lapse between CPP and GHD, years | 2.3±2.7 | −1.7±1.9 | <0.0001 |

| Time lapse between CPP and GH replacement, years | 2.9±2.8 | −0.8±1.9 | <0.0001 |

| Height (SDS) at time point A | 0.2±1.3 | −0.6±1.5 | 0.03 |

| Height (SDS) at time point A, final height attained* | 0.5±1.2 | −0.6±1.2 | 0.03 |

| BMI (SDS) at time point A | 1.5±0.9 | 1.0±1.1 | 0.05 |

| Age at time point B (Male), years | 12.2±1.4 | 12.7±1.0 | 0.37 |

| Age at time point B (Female), years | 11.0±1.3 | 11.5±1.6 | 0.63 |

| Height (SDS) at time point B | −0.07±1.3 | −0.5±1.0 | 0.16 |

| Height (SDS) at time point B, final height attained* | 0.1±1.2 | −0.6±1.2 | 0.08 |

| BMI (SDS) at time point B | 1.6±0.7 | 0.8±0.7 | 0.001 |

| Age at time point C, years | 18.7±5.0 | 17.9±5.2 | 0.5 |

| Height (SDS) at time point C | −0.8±1.2 | −0.9±1.1 | 0.82 |

| Short stature at time point C (%) | 10 (21.3%) | 3 (21.4%) | 1.00 |

| Obesity at time point C (N, %) | 21 (44.7%) | 2 (14.3 %) | 0.06 |

| Final height (SDS) * | −0.9±1.1 | −1.2±1.1 | 0.44 |

| Short stature, final height attained* | 7 (20.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 0.67 |

Group 1= Tumors located in the hypothalamus, thalamus, optic pathways, sellar or supra-sellar regions

Group 2= Tumors / cancers affecting other locations

Data is shown as mean ± standard deviations

GHD = GH deficiency

SDS= Standard deviation score

CPP= Central precocious puberty

Individuals who reached final height by time point C (n=45)

Time point A= Diagnosis of central precocious puberty

Time point B= Completion of pubertal suppression using GnRH agonist

Time point C= Latest follow-up visit

Prevalence of CPP in Patients with Primary CNS Tumor Diagnoses

Out of the 80 patients with CPP, four did not have a primary CNS tumor [acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1), acute myeloblastic leukemia (n=1), retinoblastoma with brain metastases (n=1), Wilms tumor with brain metastases (n=1)]. Out of 903 non-CPP systematically referred patients, 377 were too old at the time of tumor diagnosis to have CPP as a possible diagnosis while 102 were young enough at the last assessment to be still at risk of subsequently developing CPP. After excluding all these patients, 76 patients with CPP and 424 without CPP were retained for the estimation of the prevalence of organic CPP among at-risk patients with primary CNS tumors (Figure 1). The prevalence of CPP was 15.2% overall; 29.2% in Group 1 and 6.6% in Group 2. The prevalence varied by tumor location: optic pathways 45.1%, thalamus 36.4%, sellar/supra-sellar 21.3% (31.3% if patients with surgically induced panhypopituitarism are excluded), and posterior fossa 3.2%. The prevalence also varied by tumor type: low grade glioma (includes optic pathway glioma, juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma, low-grade astrocytoma and ganglioglioma) 30.6%, craniopharyngioma 9.9% (33.3% if patients with post-surgical pan-hypopituitarism are excluded), ependymoma 5.1% and medulloblastoma 4.5%.

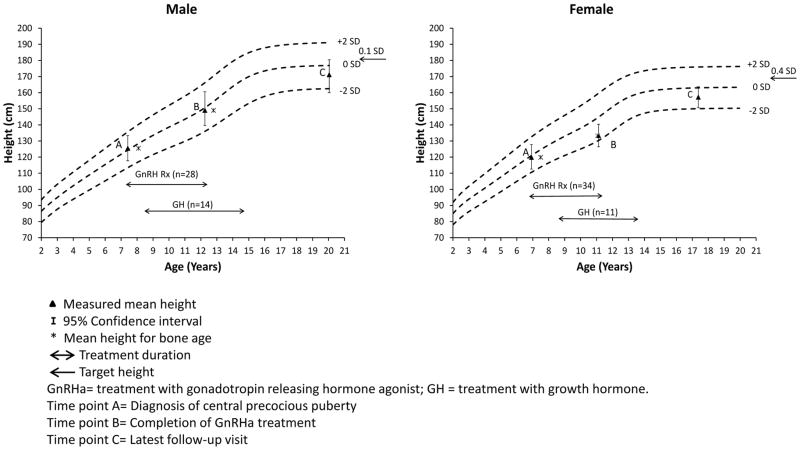

Final Height Outcome

The growth profiles of the patients are summarized in Figure 2. A total 45 patients attained their final heights and their data were used for comparisons with target and predicted heights within each time point, as well as for height comparisons across time-points. At puberty onset, the mean bone age was advanced by 0.9±1.5 years in comparison to the chronological age; the mean height (0.2±1.2 SDS) was not significantly different from the target height (0.2±0.8 SDS; p=0.32), but was significantly above the predicted height (−0.7±1.6 SDS; p<0.0001). At completion of GnRHa therapy, the mean bone age was advanced by 0.2±1.5 years, and the mean height (0.0±1.2 SDS) was not significantly different from the target height (p=0.37) or predicted height (−0.5±1.6 SDS; p=0.06). Attained final height (−0.9±1.1 SDS) was significantly lower than the target height (p<0.0001), as well as the predicted height at completion of GnRHa (p=0.02) but was not significantly different from the predicted height at the onset of puberty (p=0.52). The final height SD was also lower than height SD at completion of GnRHa (p<0.0001) and at the onset of puberty (p<0.0001) (Appendix Table A3). Height <-2SDS was more prevalent at last follow-up (21.4%) vs. at completion of GnRHa (2.4%; p=0.02) or onset of puberty (2.4%; p=0.005) (Appendix Table A3). These differences remained after the exclusion of patients with GHD with no or less than one year of GH replacement.

Figure 2.

Mean Height at Different Study Time Points Plotted on General Population Based Growth Charts for Males and Females

Appendix Table A3.

Variation in Height and Obesity Outcomes over Time

| Time points of evaluation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | A vs. B | B vs. C | C vs. A | |

| Height (SDS), all | 0.0± 1.4 | −0.2±1.3 | −0.9±1.1 | P=0.18 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 |

| Height (SDS), females | −0.2±1.4 | −0.3±1.1 | −0.9±1.0 | P=0.49 | P=0.0004 | P=0.0002 |

| Height (SDS), males | 0.2±1.4 | −0.03±1.4 | −0.8±1.3 | P=0.32 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 |

| Height (SDS), final height attained | 0.2±1.2 | 0.0±1.2 | −0.9±1.1 | P=0.18 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 |

| Predicted Height (SDS), final height attained* | −0.7±1.6 | −0.5±1.6 | −0.9±1.1** | n/a | P=0.02 | P=0.52 |

| Height (SDS), final height attained, Group 1 | 0.5±1.2 | 0.1±1.2 | −0.9±1.1 | P=0.15 | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 |

| Height (SDS), final height attained, Group 2 | −0.6±1.2 | −0.6±1.2 | −1.2±1.1 | P=0.71 | P=0.08 | P=0.15 |

| Short stature (%), all | 7.8 | 8.1 | 21.3 | P=0.65 | P=0.02 | P=0.002 |

| Short stature (%), final height attained | 2.4 | 2.4 | 21.4 | P=1.00 | P=0.02 | P=0.005 |

| Obesity (%), all | 20.8 | 22.6 | 37.7 | P=0.76 | P=0.03 | P=0.03 |

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviations

SDS= Standard deviation score

Time point A= Diagnosis of central precocious puberty

Time point B= Completion of GnRHa

Time point C= Latest follow-up visit

The target height was 0.2±0.8 SD for individuals with final height data,

measured final height

Group 1= Tumors located in the hypothalamus, thalamus, optic pathways, sellar or supra-sellar regions

Group 2= Tumors / cancers affecting other locations

There was no difference in the final height between Groups 1 and 2 (p=0.44) (Table 2). In a multivariable model (Table 3), final height<-2SDS was significantly associated with only the duration of GnRHa (OR=2.1; 95% CI 1.0–4.3; p=0.04), with each one year of additional therapy associated with a 111% increase in the odds of a final height <-2SDS. There was no multicollinearity between age at CPP and duration of GnRHa treatment in this model. GHD was not included in this model as final height <-2SDS was present in 9 of 10 patients who were GHD and only one of 11 non-GHD patients.

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis of Short Stature, Obesity and LH/FSH Deficiency (LH/FSHD) at Latest Follow-up

| Short Stature (n=45*) | Obesity (n=61†) | LH/FSHD (n=46**) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) μ | OR (95%CI) | p | N (%) μ | OR (95%CI) | p | N (%) μ | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 6 (27.3) | 1.00 | 13 (48.2) | 1.00 | 10 (41.7) | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 4 (17.4) | 0.6 (0.09–4.4) | 0.63 | 10 (29.4) | 0.57 (0.1–2.5) | 0.45 | 5 (22.7) | 0.11(0.01–1.0) | 0.05 |

| CSI | |||||||||

| No | 7 (18) | 1.00 | 21 (41.2) | 1.00 | 14(35.9) | 1.0 | |||

| Yes | 3 (50) | 1.7 (0.14–21.1) | 0.68 | 2 (20.0) | 0.9 (0.1–10.7) | 0.9 | 1 (14.3) | 0.01 (0.0001–2.8) | 0.11 |

| Group | Not included in model | ||||||||

| 1 | 7 (20.0) | 1.00 | 21 (44.7) | 1.00 | |||||

| 2 | 3 (30.0) | 1.58 (0.1–18.6) | 0.72 | 2 (14.3) | 0.25 (0.03–2.4) | 0.23 | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||||||

| Age at CPP (years) | 7.3 (1.6) | 1.8 (0.8–4.2) | 0.15 | 7.14 (1.6) | 0.90 (0.5–1.6) | 0.72 | 7.4 (1.6) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.13 |

| GnRHa duration (years) | 4.3 (2.0) | 2.1 (1.0–4.3) | 0.04 | 4.2 (1.82) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.74 | 4.3 (1.9) | 2.3 (0.9–6.0) | 0.1 |

| Follow–up time (years) | Not included in model | 11.4(5.0) | 1.34 (1.1–1.6) | 0.001 | 13.1 (4.4) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 0.18 | ||

Total number of patients with final height data;

Total number of patients available at the latest follow-up visit;

Total number of patients ≥14 years old.

μ: row percent. CSI= Cranio-spinal irradiation, CPP = central precocious puberty, GnRHa = Puberty suppression using GnRH agonist.

Puberty Outcomes and Subsequent Development of LH/FSHD, Abnormal Uterine Bleeding and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS)

A total of 15 patients developed LH/FSHD, including 6 who had no evidence of endogenous sex hormone production after the discontinuation of GnRHa. The remaining LH/FSHD cases were diagnosed 4.1 ± 3.3 years after discontinuation of GnRHa. A multivariable analysis (Table 3) did not identify any factors that were associated with the development of LH/FSHD among patients with CPP. Group, treatment with CRT and GHD were not included in this model because all patients with LH/FSHD belonged to Group 1, had GHD and all patients but one (93.3%) were treated with CRT.

Among the 18 females ≥16 years old, 14 (77.7 %) had sex hormone related complaints or diagnoses. Abnormal uterine bleeding occurred in 10 patients who had reached menarche at 13.4± 1.6 years of age and still had irregular menses 6.6± 4.5 years later (range 3.3–15.9 years). Among these patients, two had an established diagnosis of PCOS while the remaining 8 were still undergoing assessments for heavy and frequent menses (n=3), oligomenorrhea (n=3) and secondary amenorrhea (n=2). None of the patients reported ever being pregnant.

Obesity

There was no difference in the prevalence of obesity between puberty onset and completion of GnRHa therapy (Appendix Table A3). Obesity was more prevalent at the time of the last follow-up visit than at completion of GnRHa or at puberty onset. In a multivariable model (Table 3) obesity was independently associated with duration of follow-up (OR=1.3; 95% CI 1.1–1.6; p<0.001) with each additional year of follow-up increasing the odds of obesity by 34%.

Comparison to patients without CPP

Final height was not significantly different in patients with CPP and HPA low-grade glioma (−0.8± 1.5) compared to those with the same tumor diagnosis but without CPP (−1.0± 1.8; p=0.62). The multivariable analysis (Table 4) did not find independent associations between CPP and adult height SDS <-2, obesity and LH/FSHD. A significant association was found between LH/FSHD and CRT (OR=22.4; 95% CI 2.4–204.9; p=0.006).

Table 4.

Multivariable Analysis Results of Short Stature, Obesity and Gonadotropin Deficiency (LH/FSHD) for Patients with and without CPP

| Short Stature (n=63) | Obesity (n=63) | LH/FSHD* (n=63) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%)μ | OR (95%CI) | p | N (%)μ | OR (95%CI) | p | N (%)μ | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| CPP | |||||||||

| No | 4 (12.1) | 1.00 | 12 (36.4) | 1.00 | 12 (36.4) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 6 (20.0) | 1.37 (0.27–6.97) | 0.70 | 14 (46.7) | 1.54 (0.46–5.14) | 0.48 | 12 (40.0) | 0.69 (0.19–2.57) | 0.58 |

| Age at tumor diagnosis | |||||||||

| <5 years | 8 (25.0) | 1.00 | 14 (43.8) | 1.00 | 15 (46.9) | 1.00 | |||

| ≥5 years | 2 (6.5) | 0.16 (0.03–1.03) | 0.05 | 12 (38.7) | 0.91 (0.31–2.68) | 0.86 | 9 (29.0) | 0.36 (0.10–1.25) | 0.11 |

| GHD | |||||||||

| No | 2 (11.1) | 1.00 | 4 (22.2) | 1.00 | - | - | - | ||

| Yes | 8 (17.8) | 0.24 (0.02–3.12) | 0.27 | 22 (48.9) | 3.73 (0.57–24.50) | 0.17 | - | - | - |

| Type-1 neurofibromatosis | |||||||||

| No | 9 (16.4) | 1.00 | 24 (43.6) | 1.00 | 23 (41.8) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1 (12.5) | 0.28 (0.02–3.78) | 0.34 | 2 (25.0) | 0.32 (0.05–1.99) | 0.22 | 1 (12.5) | 0.11 (0.01–1.17) | 0.07 |

| Cranial radiotherapy | |||||||||

| No | 1 (5.9) | 1.00 | 5 (29.4) | 1.00 | 1 (5.9) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 9 (19.6) | 10.32 (0.46–233.71) | 0.14 | 21 (45.7) | 0.72 (0.11–4.68) | 0.73 | 23 (50.0) | 22.35 (2.44–204.90) | 0.006 |

CPP= Central precocious puberty, GHD= GH deficiency.

GHD was not included into the model since none of the patients without GHD had LH/FSHD..

μ: row percent.

Discussion

The present study reports on a variety of long-term outcomes in one of the largest clinically well characterized cohorts of patients with CPP related to a CNS tumor or CRT. The overall prevalence of CPP in the present study, which included both girls and boys, was 15.2% and was almost two-fold higher among those with HPA tumors. A previous Childhood Cancer Survivor Study investigation reported a slightly lower prevalence of CPP of 11.9% among female survivors using self-reported history of menarche before 10 years of age as a surrogate for precocious puberty 8. In a more recent study, the prevalence of CPP among patients diagnosed with childhood optic glioma was 26%. These findings place organic CPP among childhood’s most common hypothalamic pituitary dysfunctions following HPA insults and radiotherapy, second only to GHD 3, 8, 26. Interestingly, CPP tended to appear before GHD in Group 1. In subjects with optic pathway low-grade gliomas, isolated CPP is common at presentation and may occur as a result of the interplay between glial cell factors and GnRH neurons1. Thus, for this large subset of patients in Group 1, late onset GHD likely develops as a result of tumor growth, subsequent surgery and/or subsequent treatment with radiotherapy years after presenting with CPP. The high prevalence (29.2 %) of organic CPP in patients with HPA tumors highlights the need for close monitoring of the pubertal development of all children with this presentation.

The prevalence of short stature, defined as final height <-2SDS, (21.4%) among individuals who reached their adult height was nearly identical to the 25% previously reported in a study of 100 patients with organic CPP followed over a mean period of 7 years 12. In our series, final height was significantly below the target height but not significantly different from the predicted height at the onset of puberty with an average loss of 0.9 SDS. These results are in contrast to those reported by Trivin et al., where final height and target height were not significantly different in patients treated with GnRHa and GH, possibly reflecting differences between the study populations 12, 27. The association between duration of GnRHa and short stature in our study most likely reflects a tendency to prolong pubertal suppression in shorter individuals rather than a detrimental effect of the therapy itself on final height.

We were not able to show a specific effect of CPP on final height through the study of the subset patients with HPA low-grade gliomas. Limited historical data demonstrating unfavorable height outcomes in patients with untreated organic CPP allow us to speculate that the prospective follow-up of at-risk patients and early treatment of CPP may have allowed patients with CPP to reach adult heights similar to those without CPP28. The observed height-loss seen in those with and without CPP may be attributable to other factors such as delays and interruptions in GH therapy given safety concerns, constitutional factors (such as NF-1), illness, and sequelae from prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy e.g., damage to the vertebral growth plates in those exposed to spinal radiation 29–32.

The development of LH/FSHD in patients with a history of organic CPP is a paradox that is likely a consequence of delayed effects of prior CRT in those so treated as well as the result of tumor progression/surgery in the subset with HPA lesions 3, 13. Individuals with HPA tumors seem to be at particularly high risk of developing LH/FSHD, which may even develop while patients are still on GnRHa (i.e. some patients do not resume spontaneous pubertal development after the treatment is discontinued). It is not fully understood whether CPP alone, independently of a CNS insult, can have lasting consequences on gonadal function. We did not find an association between CPP and LH/FSHD in our study of patients with HPA low-grade gliomas, but as expected, we did find a significant association between LH/FSHD and CRT.

Franceschi et al. 15 reported rates of PCOS of 30–32% in individuals (ages 18± 3 years) with a history of idiopathic CPP, independent of obesity or insulin resistance. Most studies of idiopathic CPP, however, have described long-term reproductive outcomes similar to those observed in the general population 17, 33. The high prevalence of sex-hormone related complaints in our cohort may be the consequence of the metabolic dysfunctions observed in CNS tumor and CRT-treated survivors as well as, possibly, the effect of chemotherapy on the ovaries rather than of CPP itself. Primary hypogonadism is difficult to assess in patients with LH/FSHD as those individuals are unable to raise their gonadotropin levels in response to gonadal failure; additional testing and evaluation by a reproductive endocrinologist may be necessary to complete the assessment of patients who are at risk of developing both forms of hypogonadism. Long-term studies incorporating pregnancy outcomes in females and semen analyses in males will be required for the assessment of the reproductive outcomes of this patient population13.

Patients with idiopathic CPP have been shown to have obesity rates of 25% 36 months after completing treatment with GnRHa 34. In a more recent report on 142 women (ages 33.4± 4.2 years), a history of CPP was not associated with higher risks of obesity or metabolic derangements long-term despite an increase in BMI during treatment 16. The rates of obesity were high in our cohort and worsened over time; these findings may be explained by the high proportion of patients diagnosed with CNS tumors at a young age as we were not able to find an independent association between CPP and obesity in our patients with HPA low-grade gliomas 35.

The retrospective design and the size and heterogeneity of our study population need to be taken into consideration in the interpretation of our findings. Given the characteristics of our study population, the multivariable analysis is limited by the small number of patients available for assessing numerous variables and precludes our ability to detect significant interactions. In the study of patients with low-grade gliomas, gender distribution was different among patients with and without CPP and the small sample size has limited our ability to match individuals based on this important parameter.

Conclusions

CPP is among the most common complications following CNS tumors and/or CRT affecting the hypothalamus / pituitary. Patients with organic CPP experience an incomplete recovery of growth and a high prevalence of LH/FSHD and obesity but these complications seem more related to the primary diagnosis than to CPP itself. Early diagnosis and treatment of patients with CPP may limit further deterioration of final height prospects.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: The study uses data from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE). SJLIFE is supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant CA21765 and UO1 grant U01CA195547-01 from the National Cancer Institute.

The study uses data from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE). SJLIFE is supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant CA21765 and UO1 grant U01CA195547-01 from the National Cancer Institute. The authors are grateful for the assistance received from Dr. Deo Kumar Srivastava for the study design and statistical analyses. W.C. acknowledges Professor Raja Brauner for her mentorship through the years.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: Wassim Chemaitilly has accepted consulting fees from Novo Nordisk and JCR Pharmaceuticals (Japan). Leslie L Robison has accepted consulting fees from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Charles A Sklar has accepted a one-time consulting fee from Novo-Nordisk and an honorarium from Sandoz. The remaining authors have no relevant relationships to disclose.

Conflict of interest: None of the authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Reference List

- 1.Ojeda SR, Lomniczi A, Mastronardi C, et al. Minireview: the neuroendocrine regulation of puberty: is the time ripe for a systems biology approach? Endocrinology. 2006;147(3):1166–1174. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chemaitilly W, Trivin C, Adan L, et al. Central precocious puberty: clinical and laboratory features. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;54(3):289–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan HW, Phipps K, Aquilina K, et al. Neuroendocrine morbidity after pediatric optic gliomas: a longitudinal analysis of 166 children over 30 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015:jc20152028. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brauner R, Czernichow P, Rappaport R. Precocious puberty after hypothalamic and pituitary irradiation in young children. N Engl J Med. 1984;311(14):920. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198410043111414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Constine LS, Woolf PD, Cann D, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction after radiation for brain tumors. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(2):87–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301143280203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oberfield SE, Soranno D, Nirenberg A, et al. Age at onset of puberty following high-dose central nervous system radiation therapy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(6):589–592. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170310023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow EJ, Friedman DL, Yasui Y, et al. Timing of menarche among survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(4):854–858. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong GT, Whitton JA, Gajjar A, et al. Abnormal timing of menarche in survivors of central nervous system tumors: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2562–2570. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalumeau M, Chemaitilly W, Trivin C, et al. Central precocious puberty in girls: an evidence-based diagnosis tree to predict central nervous system abnormalities. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):61–67. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalumeau M, Hadjiathanasiou CG, Ng SM, et al. Selecting girls with precocious puberty for brain imaging: validation of European evidence-based diagnosis rule. J Pediatr. 2003;143(4):445–450. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor M, Couto-Silva AC, Adan L, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary lesions in pediatric patients: endocrine symptoms often precede neuro-ophthalmic presenting symptoms. J Pediatr. 2012;161(5):855–863. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trivin C, Couto-Silva AC, Sainte-Rose C, et al. Presentation and evolution of organic central precocious puberty according to the type of CNS lesion. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;65(2):239–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chemaitilly W, Sklar CA. Endocrine complications in long-term survivors of childhood cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(3):R141–R159. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuqua JS. Treatment and outcomes of precocious puberty: an update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(6):2198–2207. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franceschi R, Gaudino R, Marcolongo A, et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in young women who had idiopathic central precocious puberty. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(4):1185–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazar L, Lebenthal Y, Yackobovitch-Gavan M, et al. Treated and untreated women with idiopathic precocious puberty: BMI evolution, metabolic outcome and general health between the third and fifith decades. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(4):1445–1451. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carel JC, Eugster EA, Rogol A, et al. Consensus statement on the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e752–e762. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haber HP, Wollmann HA, Ranke MB. Pelvic ultrasonography: early differentiation between isolated premature thelarche and central precocious puberty. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154(3):182–186. doi: 10.1007/BF01954267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44(235):291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45(239):13–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pyle SI, Greulich WW. Radiographic Atlas of Skeletal Development of the Hand and Wrist. 2. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayley N, Pinneau SR. Tables for predicting adult height from skeletal age: revised for use with the Greulich-Pyle hand standards. J Pediatr. 1952;40(4):423–441. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(52)80205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanner JM, Goldstein H, Whitehouse RH. Standards for children’s height at ages 2–9 years allowing for heights of parents. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45(244):755–762. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.244.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, et al. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merchant TE, Rose SR, Bosley C, et al. Growth hormone secretion after conformal radiation therapy in pediatric patients with localized brain tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(36):4776–4780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Huang S, et al. Anterior hypopituitarism in adult survivors of childhood cancers treated with cranial radiotherapy: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(5):492–500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.7933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein KO, Barnes KM, Jones JV, et al. Increased final height in precocious puberty after long-term treatment with LHRH agonists: the National Institutes of Health experience. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(10):4711–4716. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigurjonsdottir TJ, hayes AB. Precocious puberty: a report of 96 cases. Amer J Dis Child. 1968;115:309–21. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1968.02100010311003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chemaitilly W, Robison LL. Safety of growth hormone treatment in patients previously treated for cancer. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012;41(4):785–792. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandecruys E, Dhooge C, Craen M, et al. Longitudinal linear growth and final height is impaired in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors after treatment without cranial irradiation. J Pediatr. 2013;163(1):268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clayton PE, Shalet SM. The evolution of spinal growth after irradiation. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1991;3(4):220–222. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)80744-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clementi M, Milani S, Mammi I, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 growth charts. Am J Med Genet. 1999;87(4):317–323. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19991203)87:4<317::aid-ajmg7>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neely EK, Lee PA, Bloch CA, et al. Leuprolide acetate 1-month depot for central precocious puberty: hormonal suppression and recovery. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010;2010:398639. doi: 10.1155/2010/398639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmert MR, Mansfield MJ, Crowley WF, et al. Is obesity an outcome of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist administration? Analysis of growth and body composition in 110 patients with central precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(12):4480–4488. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.12.6204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lustig RH, Post SR, Srivannaboon K, et al. Risk factors for the development of obesity in children surviving brain tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(2):611–616. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]