Abstract

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with recombinant human acid α-glucosidase (rhGAA) fails to completely reverse muscle weakness in Pompe disease. β2-agonists enhanced ERT by increasing receptor-mediated uptake of rhGAA in skeletal muscles.

Purpose

To test the hypothesis that a β-blocker might reduce the efficacy of ERT, because the action of β-blockers opposes those of β2-agonists.

Methods

Mice with Pompe disease were treated with propranolol (a β-blocker) or clenbuterol in combination with ERT, or with ERT alone.

Results

Propranolol-treated mice had decreased weight gain (p<0.01), in comparison with clenbuterol-treated mice. Left ventricular mass was decreased (and comparable to wild-type) in ERT only and clenbuterol-treated groups of mice, and unchanged in propranolol-treated mice. GAA activity increased following either clenbuterol or propranolol in skeletal muscles. However, muscle glycogen was reduced only in clenbuterol-treated mice, not in propranolol-treated mice. Cell-based experiments confirmed that propranolol reduces uptake of rhGAA into Pompe fibroblasts and also demonstrated that the drug induces intracellular accumulation of glycoproteins at higher doses.

Conclusion

Propranolol, a commonly prescribed β-blocker, increased left ventricular mass and decreased glycogen clearance in skeletal muscle following ERT. β-blockers might therefore decrease the efficacy from ERT in patients with Pompe disease.

Keywords: lysosomal storage disorder (LSD), Pompe disease, acid α-glucosidase (GAA), enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), β-blocker, propranolol

INTRODUCTION

Pompe disease (glycogen storage disease type II; acid maltase deficiency) is caused by the deficiency of lysosomal acid α-glucosidase (GAA) that leads to accumulation of lysosomal glycogen and impairment of cardiac and skeletal muscles. Treatment in the form of enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with recombinant human (rh) GAA (Myozyme®;Lumizyme® alglucosidase alfa) has shown promise in patients with Pompe disease. However, the limitations of ERT have become apparent, including requirement of high dosage compared to other lysosomal storage disease and the lack of complete reversal of muscle weakness.1 The enzyme dosages required for ERT in Pompe disease range up to 100-fold greater than those for other lysosomal disorders.2 In previous studies3,4, the cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (CI-MPR) was implicated in GAA uptake from blood stream to target tissues/cells. Since CI-MPR is expressed at low levels in skeletal muscle, high dosages of rhGAA were required to achieve efficacy from ERT.5 In our previous study6, low expression of CI-MPR in skeletal muscle reduced efficacy from ERT in mice with Pompe disease and increased CI-MPR-mediated uptake of rhGAA from simultaneous β2-agonist administration increased efficacy. Similarly, β2-agonist treatment also improved efficacy from AAV-based gene therapy in GAA knockout (KO) mice with Pompe disease.7,8

Pompe disease leads to a severe dysfunction of cardiac muscle, other cardiac manifestations include left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and cardiac rhythm disturbances including atrial fibrillation and supraventricular tachycardia often requiring treatment with β-blockers. The latter are also used to treat hypertension. Propranolol is a non-selective β-blocker that is still prescribed for individuals with Pompe disease for the above-mentioned indications (personal observations).9 According to our previous findings with β2-agonists3,6–8, adequate function of β-adrenergic receptors might be critical for the enhancement of therapeutic benefits in Pompe therapy. Currently, we speculated that treatment with a β-blocker might not enhance efficacy, as did β2-agonists during ERT in patients with Pompe disease10, but would actually reduce efficacy. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Pompe disease had recommended caution due to reports of mortality associated with the use of β-blockers.11 To evaluate the possibility of toxicity from a β-blocker, GAA-KO mice and Pompe fibroblasts were treated with propranolol, in combination with rhGAA to evaluate the effect of this drug upon efficacy from ERT in the context of Pompe disease. The impact of these findings on the treatment of patients with lysosomal storage disorders is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Studies

All animal procedures were performed under the guidelines of Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Two-month old GAA-KO mice performed Rotarod and wirehang tests before stating treatment of drugs. The GAA-KO mice were divided into 4 groups: no treatment control (n=8); ERT alone (n=4); ERT with clenbuterol (n=10); and ERT with propranolol (n=7). Clenbuterol was provided in drinking water (30 mg/l; 8.4 mg/kg/day)3, as was the β-blocker propranolol (170 mg/l; 40 mg/kg/day).12 One week following initiation of drug therapy, intravenous rhGAA (20 mg/kg; Genzyme Corporation) was administrated weekly through tail-vein injection for 4 weeks. Five days after the last injection of rhGAA, Rotarod and wirehang tests were performed to evaluate muscle function. Two days later mice were euthanized for evaluation of body weight, ventricular mass of heart, and left ventricular mass (after removing the right ventricle). Skeletal muscle mass was measured using the gastrocnemius of hind limb. Several tissues including cardiac, skeletal muscle, and liver were collected and frozen prior to further evaluation including GAA activity and glycogen content as described3.

Cell Studies

For uptake experiments, Pompe fibroblasts (GM04912; Coriell Cell Repository, Camden, NJ) were treated with various doses of propranolol or clenbuterol, in combination with 30µg/mL rhGAA, for 5 h prior to analysis. The extent of enzyme uptake was determined by assaying GAA activity in cell lysates using the fluorescent substrate, 4-methylumbelliferyl-α-glucoside. All analyses were carried out in triplicate within three independent experiments.

For staining experiments, Pompe fibroblasts were incubated with 50µM percacetylated azide-modified N-acetylgalactosamine (Ac4GalNAz; incorporates into protein-bound N- and O-linked sugar chains) in the presence of various concentrations of clenbuterol or propranolol for 15 h. Following treatment, cells were incubated with dibenzocyclooctyne (DIBO) reagent to install biotin onto labeled sugar chains, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, and incubated with a Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-biotin antibody. Stained cells were visualized on an FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope and the percentage of cells with accumulation of labeled glycoproteins determined by counting cells that exhibit overt storage phenotype. Quantification of glycoprotein accumulation was performed on at least 100 stained cells from three independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism5 (GraphPad Software, Inc). Multiple comparisons were performed using One Way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison test. The statistical significance of comparisons is indicated as follows (* = <0.05; ** = <0.01, or *** = <0.001).

RESULTS

Efficacy from ERT was abrogated by propranolol administration

As shown in experimental scheme (Figure 1A), GAA-KO mice were treated with 4 weekly doses of ERT. Neither, administration of the β-agonist (clenbuterol) nor the β-blocker (propranolol) prevented the anticipated antibody response to ERT with rhGAA in these GAA-KO mice (data not shown), and antibody responses have been associated with reduced efficacy from ERT in GAA-KO mice.13 However, propranolol-treated GAA-KO mice appeared ill and failed to gain body weight following ERT, in comparison with mice treated with ERT alone or ERT and clenbuterol (Figure 1B). Consistent with a previous study of clenbuterol and ERT in GAA-KO mice6, clenbuterol increased the mass of the gastrocnemius muscle (Figure 1C). Propranolol treatment slightly reduced gastrocnemius mass, in comparison with mice treated with ERT alone or with clenbuterol and ERT.

Figure 1. Experimental Scheme, Body and Muscle Weight.

(A) Design of Study. Mice were treated for 5 weeks with ERT consisting of 4 weekly injections of rhGAA (20 mg/kg), either alone or in combination with clenbuterol (8.4 mg/kg/day) or propranolol (40 mg/kg/day). Drug treatment started one week prior to ERT and was continued for the duration of the experiment. To evaluate alterations of body weight and mass of cardiac and skeletal muscles, GAA-KO mice were evaluated for body weight (B), gastrocnemius weight (C), and cardiac muscle weights (D). Mean +/− standard deviation is shown. P<0.05 (*),. P<0.01 (**), and P<0.001 (***).

Left ventricular mass was increased following propranolol administration during ERT

Patients with infantile Pompe disease develop hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and increased cardiac ventricular mass has been reported in GAA-KO mice with Pompe disease.14,15 We observed reduction of left ventricular mass following ERT in GAA-KO mice (Figure 1D), and the ratio of left ventricle mass to body weight was reduced to approximately 3.8, which is comparable to 3.0–3.5 of healthy mice.16,17 However, propranolol administration prevented any reduction of left ventricular mass, in comparison with untreated GAA-KO mice (Figure 1D). The reduction of ventricular mass by ERT in Pompe mice was generalized, and not limited to the left ventricle, because the ratio of left ventricle mass to total ventricular mass was not changed by ERT, in comparison with untreated GAA-KO mice (not shown). The ratio of left/total ventricle mass ratio would be lower in the ERT group, in comparison with the untreated group, if only the left ventricle mass was reduced by ERT.

Clenbuterol treatment was beneficial by increasing Rotarod latency (Figure 2A) and wirehang latency (Figure 2B), in comparison with ERT alone. Propranolol treatment reduced Rotarod latency, in comparison with untreated GAA-KO mice (Figure 2A). Propranolol with ERT did increase Rotarod latency suggesting an improvement in neuromuscular function, in comparison with ERT alone (Figure 2A). However, propranolol with ERT reduced wirehang latency indicating reduced muscle strength, in comparison with clenbuterol and ERT (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Muscle Function Testing.

(A) Latency change on Rotarod and (B) latency change in wirehang for each treatment group. Groups included: No Treatment (n=8); ERT alone (n=4); ERT with clenbuterol (n=10); and ERT with propranolol (n=7). Mean +/− standard deviation is shown. P<0.05 (*),. P<0.01 (**), and P<0.001 (***).

Propranolol administration impaired the clearance of accumulated glycogen from the diaphragm

All experimental mice were euthanized one week after the 4th-injection of rhGAA for evaluation of biochemical correction as determined by GAA activity and glycogen content of striated muscles. Although GAA activity was increased in the liver following ERT, no significant increase in GAA activity in the muscle of ERT-treated mice was detected (Figure 3A). However, ERT with or without drug treatment reduced glycogen content in the heart to a similar extent (Figure 3B). ERT alone significantly reduced the glycogen content in the diaphragm, while adding propranolol prevented that effect (Figure 3B). Furthermore, administering propranolol alone increased the glycogen content of diaphragm, in comparison with untreated GAA-KO mice (Figure 3B). The lack of biochemical efficacy from GAA in the presence of propranolol further supported the relevance of β-adrenergic stimulation during ERT in Pompe disease, and implied that GAA trafficking to the lysosomes was impaired by the β-blocker.

Figure 3. Assessment of Biochemical Parameters.

To evaluate drug effect in biochemical levels, several different muscles were collected to perform (A) GAA assay and (B) Glycogen content assay. Mean +/− standard deviation is shown. P<0.05 (*),. P<0.01 (**), and P<0.001 (***).

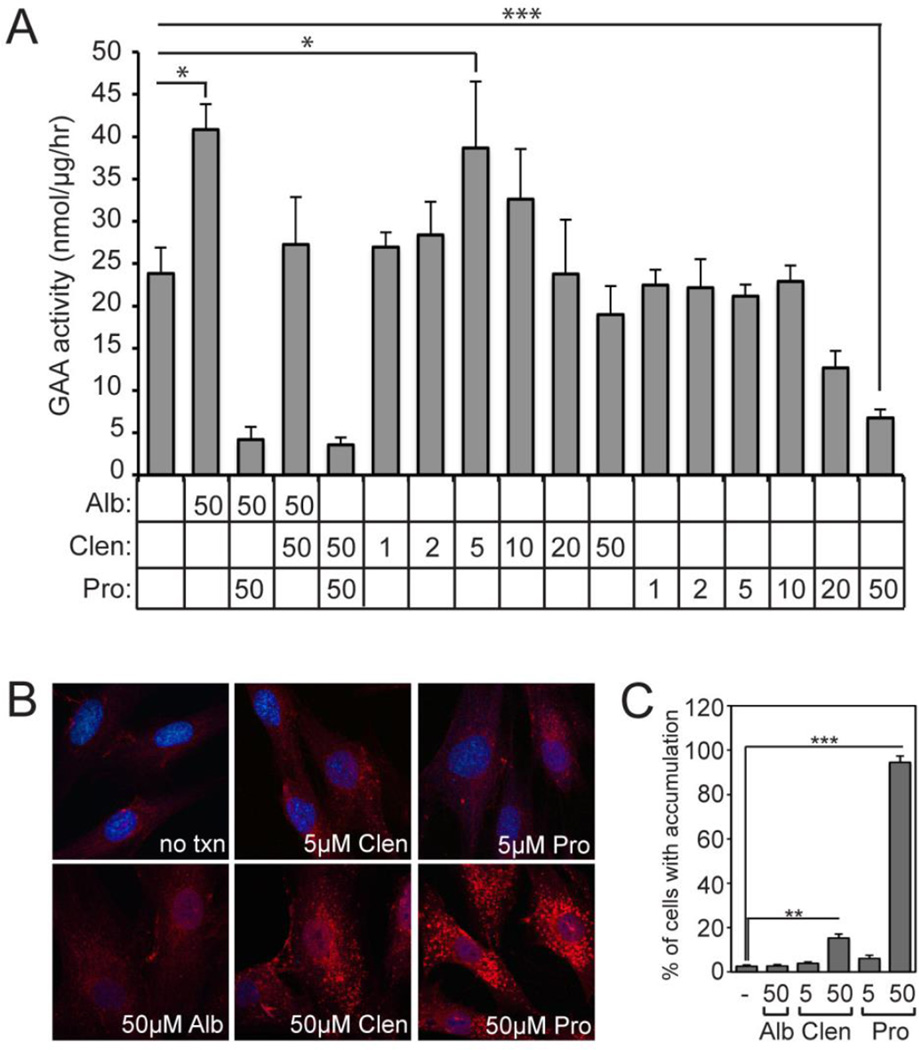

Propranolol treatment results in a dose-dependent decrease in rhGAA uptake into Pompe fibroblasts

To better understand the effects of propranolol on ERT at a cellular level, Pompe patient fibroblasts were cultured with rhGAA in the presence of β-agonists clenbuterol or albuterol, β-blocker propranolol, or a combination of the drugs (Figure 4A). These results showed a two-fold stimulation of rhGAA uptake in cells treated with 50 µM albuterol. This effect was completely ablated upon addition of 50 µM propranolol, demonstrating that the β-blocker fully blocks the positive effects of the β-agonist. This analysis also showed that clenbuterol treatment results in similar stimulation of uptake in the low µM dose range. In contrast, low doses of propranolol had no effect on uptake but higher doses (20–50 µM) lead to a dramatic decrease in rhGAA uptake. To address the potential mechanism of action, Pompe patient fibroblasts treated with 5 or 50µM propranolol were metabolically labeled with azide-modified N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAz) to visualize glycoproteins (Figure 4B). Consistent with reports that document endolysosomal dysfunction in the presence of propranolol18,19, clear accumulation of labeled glycoproteins was seen at 50 µM (but not 5 µM) propranolol, indicating that some of the negative effects of propranolol may arise due to its ability to cause altered recycling and/or storage of glycoproteins.

Figure 4. Effects of Clenbuterol and Propranolol on Enzyme Uptake into Pompe Fibroblasts.

(A) Pompe fibroblasts were incubated with rhGAA in the presence of albuterol (Alb), clenbuterol (Clen) or propranolol (Pro) for 5 h and the amount of enzyme activity taken up by the cells was monitored. All concentrations are µM. Error bars represent standard deviations (n=3). (B) Pompe fibroblasts treated with various concentrations of propranolol or clenbuterol were labeled with azide-modified sugar (GalNAz) and visualized by confocal microscopy following chemical installation of a biotin group. Accumulation of labeled glycoproteins in endolysosomal vesicles is readily apparent in cells treated with higher doses of propranolol but not clenbuterol. (C) Percentages represent the average number of cells that demonstrate an overt storage or accumulation phenotype under the stated conditions. Concentrations are shown as µM. Error bars represent standard deviations (n=3).

DISCUSSION

Pompe disease causes the generalized accumulation of lysosomal glycogen, with cardiac and skeletal muscle being the most severely affected tissues. Clinical manifestations include muscle weakness, respiratory compromise, and cardiomyopathy in the infantile form of Pompe disease. ERT using rhGAA was approved in 2006, and it is currently the only FDA approved therapy for Pompe patients. Although ERT has significantly improved and prolonged survival rate of Pompe patients, it is limited by inefficient uptake of rhGAA in skeletal muscles. From our previous studies3,6–8, the limitation of GAA uptake in skeletal muscles, especially in those comprised of type II myofibers, was attributed to the low expression of CI-MPR, which mediates GAA uptake and trafficking from the extracellular space and trafficking to the lysosomes4,20. Although we demonstrated an in vitro effect upon the trafficking of glycoproteins to the lysosomes from a high concentration of propranolol, we could not detect that effect in vivo due to the limitations of determining GAA activity in homogenized muscle. Our current study demonstrated the importance of β-adrenergic receptor function during ERT in Pompe disease, and we were able to further confirm this by showing decreased efficacy following propranolol administration. Treating with propranolol during ERT decreased weight gain, prevented muscle hypertrophy, increased left ventricular mass, and increased the increased glycogen content in the diaphragm, in comparison with ERT alone.

Currently we observed that ERT reduced left ventricular mass and glycogen accumulation in diaphragm, and that the beneficial effect of ERT was completely blocked by the administration of propranolol. The diaphragm, a sheet of internal skeletal muscle with 60% of type II fiber, is affected severely in Pompe patients resulting in poor diaphragmatic action on the abdominal expansion.21,22 According to a recent report, seven out of ten Pompe patients were found to have functional diaphragmatic weakness.23 Providing ERT with rhGAA in Pompe patients stabilized pulmonary function and reduced left ventricular mass along with glycogen clearance in diaphragm.24 Thus, reduced efficacy from concurrent propranolol treatment during ERT could reduce efficacy with regard to cardiopulmonary function.

The involvement of β2-adrenergic receptor signaling is well established in muscle hypertrophy of both cardiac and skeletal muscles through Akt/mTOR pathway.25–27 Although the mechanism is not fully clarified, skeletal muscle atrophy and cardiac muscle hypertrophy are well known phenomena in Pompe patients. Although the mechanism remains to be defined, if it is more complex than simply reducing accumulations of lysosomal glycogen, we have demonstrated that ERT with rhGAA can attenuate skeletal muscle atrophy and cardiac muscle hypertrophy in Pompe animals. Clenbuterol administration induced hypertrophy of skeletal muscle, but not cardiac muscle (Figure 2B–C). However, propranolol treatment showed a quite different effect in the muscles. The current dose of propranolol was beneficial in iron-overloaded mice12, and would be within the recommended maintenance dose range of 120–240 mg/kg/day (Drugs.com) given a conversion of the murine dose of 40 mg/kg/day to a human equivalent dose of 3.2 mg/kg/day.28 In the gastrocnemius, we found that propranolol blocked muscle hypertrophy. In cardiac muscle, however, propranolol induced cardiac hypertrophy. In addition, the reduction in ventricular hypertrophy might not be related to glycogen clearance, because glycogen content in the heart was similar between propranolol-treated mice and those treated with ERT alone or clenbuterol and ERT (Figure 3B). Intriguingly, a beneficial effect of exercise independent of glycogen clearance was reported during ERT in GAA-KO mice29. Therefore, we consider glycogen accumulation to be an index of severity of Pompe disease, but accumulated glycogen itself might not be the cause for muscle involvement including cardiac hypertrophy and atrophy of skeletal muscle.

Although propranolol treatment led to an increase in GAA uptake into muscle, the drug resulted in a clear dose-dependent decrease in rhGAA uptake in Pompe fibroblasts. The basis for this difference is not clear at this time but may reflect differences in the uptake and accumulation of propranolol in different tissues or cell types. It is also possible that the concentration of propranolol in vivo is sufficiently low to provide some beneficial effect on uptake. In light of the fact that amine-containing drugs such as propranolol can accumulate inside lysosomes in a time-dependent fashion30, sustained treatment with beta-blockers, even at low initial doses, could ultimately exhibit negative effects. Regardless, the fact that the increased rhGAA uptake does not result in increased glycogen clearance in muscle points to a secondary consequence of β-blocker treatment. The cell-based studies highlight one potential mechanism to explain lack of glycogen clearance. Our results clearly show that the same concentration of propranolol that inhibits uptake also leads to accumulation of labeled glycoproteins. Several reports have documented the ability of amine-containing drugs to accumulate in lysosomes due to an ion-trapping mechanism.18,19 This accumulation can disrupt normal lysosomal activity and alter vesicular pH in other compartments, both of which may then result in altered recycling of key receptors such as CI-MPR or effective delivery of endocytosed proteins to the lysosome. To our knowledge, this is the first report to document the negative effects of the β-blocker, propranolol on ERT in the context of Pompe disease. In light of the common use of β-blockers in patients with lysosomal storage disorders, the present results suggest that β-blocker use in patients on an ERT regimen should be carefully considered and alternative cardiac medications should be sought when possible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Duke Translational Medicine Institute/Duke CTSA, the Alice and Y.-T. Chen Pediatric Genetics and Genomics Center, and a grant from the National Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) Society to Drs. Steet and Koeberl. DDK was supported by NIH Grant R01 HL081122 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and by NIH Grant R01AR065873 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disorders. RAS was supported by NIH Grant GM086524 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. GAA-KO mice were provided courtesy of Dr. Nina Raben at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disorders, and rhGAA (Myozyme®; alglucosidase alfa) was provided by Genzyme, Co. We thank Dr. Heather Flanagan-Steet and Dr. Seokho Yu at the University of Georgia for assistance with the glycoprotein labeling experiments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maga JA, Zhou J, Kambampati R, et al. Glycosylation-independent lysosomal targeting of acid alpha-glucosidase enhances muscle glycogen clearance in pompe mice. J Biol Chem. 2013 Jan 18;288(3):1428–1438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.438663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desnick RJ. Enzyme replacement and enhancement therapies for lysosomal diseases. J Inher Metab Dis. 2004;27(3):385–410. doi: 10.1023/B:BOLI.0000031101.12838.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koeberl DD, Luo X, Sun B, et al. Enhanced efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy in Pompe disease through mannose-6-phosphate receptor expression in skeletal muscle. Mol Genet Metab. 2011 Jun;103(2):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun B, Zhang H, Benjamin DK, Jr, et al. Enhanced efficacy of an AAV vector encoding chimeric, highly secreted acid alpha-glucosidase in glycogen storage disease type II. Mol Ther. 2006 Dec;14(6):822–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raben N, Danon M, Gilbert AL, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy in the mouse model of Pompe disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2003 Sep-Oct;80(1–2):159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koeberl DD, Li S, Dai J, Thurberg BL, Bali D, Kishnani PS. Beta2 Agonists enhance the efficacy of simultaneous enzyme replacement therapy in murine Pompe disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2012 Feb;105(2):221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farah BL, Madden L, Li S, et al. Adjunctive beta2-agonist treatment reduces glycogen independently of receptor-mediated acid alpha-glucosidase uptake in the limb muscles of mice with Pompe disease. FASEB J. 2014 Jan 21; doi: 10.1096/fj.13-244202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S, Sun B, Nilsson MI, et al. Adjunctive beta2-agonists reverse neuromuscular involvement in murine Pompe disease. FASEB J. 2013 Jan;27(1):34–44. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-207472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chrysant SG, Chrysant GS. Current status of beta-blockers for the treatment of hypertension: an update. Drugs Today. 2012 May;48(5):353–366. doi: 10.1358/dot.2012.48.5.1782932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koeberl DD, Austin S, Case LE, et al. Adjunctive albuterol enhances the response to enzyme replacement therapy in late-onset Pompe disease. FASEB J. 2014 May;28(5):2171–2176. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-241893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kishnani PS, Steiner RD, Bali D, et al. Pompe disease diagnosis and management guideline. Genet Med. 2006;8(5):267–288. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000218152.87434.f3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Musumeci M, Maccari S, Sestili P, et al. The C57BL/6 genetic background confers cardioprotection in iron-overloaded mice. Blood Transfus. 2013 Jan;11(1):88–93. doi: 10.2450/2012.0176-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun B, Kulis MD, Young SP, et al. Immunomodulatory gene therapy prevents antibody formation and lethal hypersensitivity reactions in murine pompe disease. Mol Ther. 2010 Feb;18(2):353–360. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mah C, Pacak CA, Cresawn KO, et al. Physiological correction of Pompe disease by systemic delivery of adeno-associated virus serotype 1 vectors. Mol Ther. 2007 Mar;15(3):501–507. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ansong AK, Li JS, Nozik-Grayck E, et al. Electrocardiographic response to enzyme replacement therapy for Pompe disease. Genet Med. 2006 May;8(5):297–301. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000195896.04069.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manning BS, Shotwell K, Mao L, Rockman HA, Koch WJ. Physiological induction of a beta-adrenergic receptor kinase inhibitor transgene preserves ss-adrenergic responsiveness in pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2000 Nov 28;102(22):2751–2757. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.22.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan L, Vatner SF, Vatner DE. Disruption of type 5 adenylyl cyclase prevents beta-adrenergic receptor cardiomyopathy: a novel approach to beta-adrenergic receptor blockade. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014 Nov 15;307(10):H1521–H1528. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00491.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cramb G. Selective lysosomal uptake and accumulation of the beta-adrenergic antagonist propranolol in cultured and isolated cell systems. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986 Apr 15;35(8):1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldman SD, Funk RS, Rajewski RA, Krise JP. Mechanisms of amine accumulation in, egress from, lysosomes. Bioanalysis. 2009 Nov;1(8):1445–1459. doi: 10.4155/bio.09.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raben N, Fukuda T, Gilbert AL, et al. Replacing acid alpha-glucosidase in Pompe disease: recombinant and transgenic enzymes are equipotent, but neither completely clears glycogen from type II muscle fibers. Mol Ther. 2005 Jan;11(1):48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Remiche G, Lo Mauro A, Tarsia P, et al. Postural effects on lung and chest wall volumes in late onset type II glycogenosis patients. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013 May 1;186(3):308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sieck GC, Lewis MI, Blanco CE. Effects of undernutrition on diaphragm fiber size, SDH activity, and fatigue resistance. J Appl Physiol. 1989 May;66(5):2196–2205. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.5.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaeta M, Barca E, Ruggeri P, et al. Late-onset Pompe disease (LOPD): correlations between respiratory muscles CT and MRI features and pulmonary function. MolGenet Metab. 2013 Nov;110(3):290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishnani PS, Corzo D, Nicolino M, et al. Recombinant human acid {alpha}-glucosidase: Major clinical benefits in infantile-onset Pompe disease. Neurology. 2007;68(2):99–109. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251268.41188.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman EP, Nader GA. Balancing muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Nat Med. 2004 Jun;10(6):584–585. doi: 10.1038/nm0604-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chimenti C, Padua L, Pazzaglia C, et al. Cardiac and skeletal myopathy in Fabry disease: a clinicopathologic correlative study. Human Pathol. 2012 Sep;43(9):1444–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodine SC, Stitt TN, Gonzalez M, et al. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2001 Nov;3(11):1014–1019. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reagan-Shaw S, Nihal M, Ahmad N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 2008 Mar;22(3):659–661. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9574LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsson MI, Samjoo IA, Hettinga BP, et al. Aerobic training as an adjunctive therapy to enzyme replacement in Pompe disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2012 Nov;107(3):469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Logan R, Kong AC, Krise JP. Time-dependent effects of hydrophobic amine-containing drugs on lysosome structure and biogenesis in cultured human fibroblasts. J Pharmaceut Sci. 2014 Oct;103(10):3287–3296. doi: 10.1002/jps.24087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]