Abstract

Sexual minority youth were found to be more likely to drink alcohol during weekdays compared to heterosexual youth. Drinking during weekdays was associated with consuming alcohol as a coping strategy. Sexual minority youth also more frequently consumed alcohol to eliminate personal worries (coping) and to not be excluded by their peers (conformity). Sexual orientation-related alcohol problems should be addressed at an early stage. Such efforts are likely to be effective if insecurities and stress related to sexual orientation are addressed as well.

Same-sex attracted youth have been shown to have higher rates of alcohol use than youth without same-sex attraction (e.g., Goldbach, Tanner-Smith, Bagwell, & Dunlap, 2014; Corliss, Rosario, Wypij, Fisher & Austin, 2008). The Minority Stress Model can help to understand such differences. According to this Model, lesbian, gay and bisexual persons experience specific stressors related to their social position as members of a sexual minority group; such stressors include rejection, internalization of negative attitudes, and emotional distress related to the lack of acceptance (Meyer, 1995; 2003; Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002). Having to cope with this array of social and psychological stressors might result in negative behavioral health outcomes such as substance use (Hughes & Eliason, 2002).

Recent studies have explored the unique impact of minority stress as a risk factor for alcohol abuse. For instance, experiences with discrimination were found to be associated with alcohol-related problems, such as neglecting responsibilities as a result of drinking, among ethnic minorities and lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults (Borell, Jacobs, Williams, Pletcher, Houston, & Kiefe, 2007; Gee, Delva, & Takeuchi, 2007, McCabe, Bostwick, Hugher, West, & Boyd, 2010). Findings from a study among college students suggest that this association is mediated by drinking to cope with negative emotions, and that this mediation is stronger in sexual minorities (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme. 2011).

Early and heavy use of alcohol has been found to predict difficulties with alcohol consumption in adulthood (e.g., Merline, Jager, & Schulenberg, 2008; Zucker, 2008). To understand early use from a developmental perspective, it is important to also consider reasons for using alcohol (Patrick, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Johnson, & Bachman, 2011; Schulenberg & Zarret, 2006). Four alcohol use motivations have been identified in adolescents, namely social (e.g., to have fun with friends), enhancement (e.g., experiencing excitement), coping (e.g., to forget problems), and conformity (e.g., to fit in with a peer group)(Cooper, 1994; Cooper, Russell, Skinner, & Windle, 1992; Patrick et al., 2011). Of particular interest are the motives coping with personal worries and conformity to or not to be excluded from the group, because these motives have been shown to be consistently and most strongly associated with alcohol-related problems (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005). However, little is known about how these motives vary with sexual orientation.

In the present study we explored sexual orientation-related differences in the prevalence and quantity of actual alcohol use and the drinking motives to cope with personal worries and to conform to or not to be excluded from the group. Additionally, we examined whether differences in motives for drinking mediated the association between sexual orientation and actual use.

Method

In total 703 Dutch adolescents, recruited at four secondary schools, took part in this study (305 boys and 398 girls; Mage = 16.38, SD = 0.94; range = 14 to 20 years). Only students in Years 4 (52.2%), 5 (37.7%), and 6 (9.1%) of these secondary schools participated. In the Dutch secondary school system, Year 4 students are 15–16 years old, and Year 5 and Year 6 students are 16–17 and 17–18 years old, respectively. In terms of ethnicity, 86.6% of the sample was Dutch/Western European. Almost forty-seven percent of the adolescents attended a school of general education; 53.3% was enrolled in pre-academic education. School principals informed parents of students in about the study and asked them to notify the researchers if they did not allow their offspring to participate. Assenting adolescents filled in a questionnaire during class hours.

As an operationalization of sexual orientation we asked participants to indicate how often they have feelings of same-sex attraction (1 = never, 5 = very often). Those who reported any attraction to someone of the same sex were grouped in the same-sex attraction category. Outcome variables were alcohol use in general (1= no, 2 = yes), use during weekdays (1= no, 2 = yes) and weekends (1= no, 2 = yes), and quantity of use on a weekday and during the weekend (answer categories for both variables: 1 = 1 glass, 8 = 11 or more). The time frame for all alcohol use assessments was the last four weeks. Participants who reported any alcohol use were asked to fill out two scales of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (Kuntsche & Kuntsche, 2009) that assessed drinking to cope with personal worries (e.g., “In the last 12 months, how often did you drink because it helps you when you feel depressed or nervous”) and drinking to conform to or not to be excluded from the group (e.g., “In the last 12 months, how often did you drink so you won’t feel left out?”) (3 items for each scale; 1 = never a motive, 3 = almost always a motive). Cronbach’s alphas are .78 (coping with personal worries) and .66 (conformity).

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20 statistical software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). Chi-square tests and analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used for the analyses of categorical and continuous variables, respectively. To investigate the mediation effect of both drinking motives on the association between sexual orientation and alcohol use we carried out multiple mediation and bootstrap analysis using Hayes’ PROCESS macro for SPSS. In a bootstrapping analysis, random samples are generated based on the original data. In the current analysis, the bootstrapped mediation was done with 10,000 resamples. The mediator variables are significant when the obtained CI does not contain the value 0 (Hayes, 2013).

Results

Of the participants, 10.1% reported any same-sex attraction; more girls did so than boys. Youth with and without same-sex attraction did not differ in age, ethnicity, school type and class (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Demographic and alcohol usage by Same-Sex Attraction (SSA)

| No SSA | SSA | X2 or F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Demographic | ||||

| Gender, % (no.) | 3.88 | .049 | ||

| Male | 44.6 (282) | 32.4 (23) | ||

| Female | 55.4 (350) | 67.6 (48) | ||

| Age, y, Mean (SD) | 16.38 (0.94) | 16.41 (0.97) | 0.08 | .785 |

| Ethnic background, % (no.) | 0.32 | .573 | ||

| Dutch/Western | 86.3(543) | 88.7 (63) | ||

| Non-Western | 13.7(086) | 11.3 (08) | ||

| School type, % (No.) | 1.50 | .221 | ||

| General | 45.9 (290) | 53.5 (38) | ||

| Preacademic | 54.1 (342) | 46.5 (33) | ||

| Class, % (No.)1 | 0.77 | .681 | ||

| Fourth year | 53.0 (335) | 54.9 (39) | ||

| Fifth year | 38.1 (241) | 33.8 (24) | ||

| Sixth year | 008.9 (056) | 11.3 (08) | ||

| Alcohol usage | ||||

| Prevalence | ||||

| General alcohol use, % (no.) | 84.0 (531) | 84.5 (60) | 0.01 | .915 |

| Drinking during weekdays, % (no.)2 | 44.4 (235) | 58.3 (35) | 4.20 | .040 |

| Drinking during weekends, % (no.)2 | 77.3 (409) | 73.3 (44) | 0.48 | .448 |

| Quantity of alcohol use per day | ||||

| During weekdays3 | 2.54 (1.78) | 2.44 (1.65) | 00.07 | .791 |

| During weekends4 | 4.37 (2.08) | 4.23 (2.38) | 00.19 | .667 |

| Drinking Motives2,5 | ||||

| Coping, Mean (SD) | 1.27 (0.41) | 1.53 (0.58) | 19.98 | <.0001 |

| Conformity, Mean (SD) | 1.13 (0.29) | 1.36 (0.50) | 28.06 | <.0001 |

In Dutch secondary schools students are in the fourth 15–16 year old, and in the fifth and sixth year 16–17 and 17–18, respectively.

Based on those adolescents who reported alcohol usage;

Based on those adolescents who reported alcohol usage during weekdays the last 4 weeks. Absolute range is 1–7 (similar for No SSA and SSA), where 1 = 1 glass −7 = 7 – 10 glasses;

Based on those adolescents who reported alcohol usage in the weekend during last 4 weeks. Absolute range is 1–8 (similar for No SSA and SSA), where 1 = 1 glass − 8 = 11 glasses;

Absolute range is 1–3 (overall and SSA) and 1-2.33 (No SSA), where 1 = low score and 3 = high score on drinking motive

Most participants (84.1%; n = 591) reported using any alcohol: 45.8% reported to drink during weekdays and 76.9% in weekends. As shown in Table 1, same-sex attracted youth were more likely to drink on weekdays than heterosexual youth. The difference in drinking during weekends between same-sex attracted and heterosexual youth was not significant. Quantity of alcohol used on a weekday or day in the weekend did not differ significantly in relation to sexual orientation. Same-sex attracted youth scored higher on both drinking motives (coping with personal worries and conformity) (Table 1).

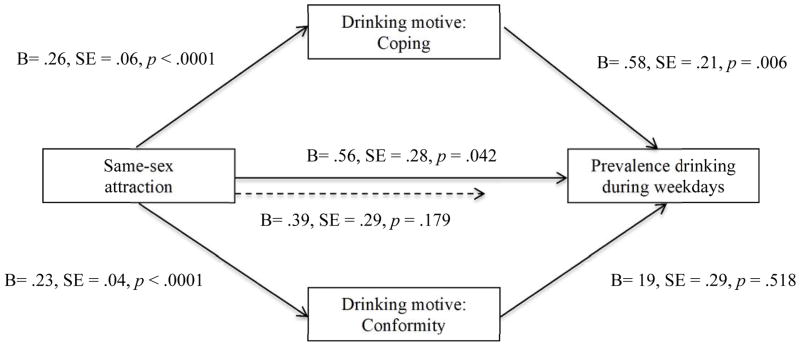

The mediation analysis confirmed that coping to deal with personal worries as drinking motive mediated the relation between sexual orientation and drinking during weekdays (95% CI = .04 — .33). Conformity as drinking motive was not found to be a mediator (95% CI = −.07. — .23). The mediation effect of the coping motive was in the expected direction. As shown in Figure 1, persons with same-sex attraction had higher levels of drinking to cope with personal worries and the higher levels of this motive the more likely alcohol had been consumed during weekdays. We also found that the direct significant effect of same-sex attraction on use of alcohol during weekdays disappeared after including this drinking motive in the mediation model, indicating that there was a full mediation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Findings of the Multiple Mediation Analysis of Drinking Motives Coping and Conformity as Mediators of the Association between Same-Sex Attraction and the Prevalence of Drinking during Weekdays

An additional bootstrapped moderated mediation analysis (Hayes, 2013) showed that the established mediation effect was stronger for boys (b = .33, 95% CI = .09 — .75) than for girls (b = .09, 95% CI = .01 — .24). Because other outcome variables (drinking during weekends, quantity of alcohol consumption during weekdays and weekends) were not associated with sexual orientation, no further mediation analyses were conducted.

Discussion

We found that same-sex attracted youth were more likely than heterosexual youth to consume alcohol during weekdays and were also more likely to drink because of coping with personal worries and drinking to conform to or not to be excluded from the group. The association between sexual orientation and the drinking motive coping (but not conformity) predicted the higher prevalence of drinking during weekdays in sexual minority youth; this effect was stronger in boys than in girls. We did not find significant differences in relation to sexual orientation for the other alcohol variables (drinking during weekends, quantity of alcohol use).

The more frequent consumption of alcohol to cope with personal worries among sexual minority youth compared to heterosexual youth is in line with findings regarding other maladaptive coping styles that have been found to explain psychological health disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth (Bos, Van Beusekom, & Sandfort, 2014). Our study also confirms the finding that the mediation effect of drinking to cope with negative emotions on the relationship between discrimination and alcohol-related problems was stronger for lesbian, gay and bisexual students than for heterosexual students (Borell et al., 2007).

Compared to most other studies that looked at sexual orientation and alcohol use, our study sample was relatively young (Borell et al., 2007; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2011). Because of this relatively young age we operationalized same-sex sexual orientation as having feelings of same-sex attraction. Other dimensions of sexual orientation (such as self-labeling or behavior) were not assessed. As a consequence it is not clear whether our findings speak to youth who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual.

Based on our findings we recommend that alcohol prevention targeting youth should pay specific attention to lesbian, gay and bisexual youth. Furthermore, the findings suggest that in working with same-sex attracted youth, the focus should be on helping them to create awareness of why they drink alcohol in order to reduce their alcohol behavior and encourage coping self-efficacy. Because alcohol consumption might be elevated in this population due to insecurities about one’s sexual identity or experienced stigma (Corllis et al., 2008), interventions could also address identity formation and strengthen coping with stigma.

Contributor Information

Henny Bos, Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Research Institute of Child Development and Education, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Gabriël van Beusekom, Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Research Institute of Child Development and Education, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Theo Sandfort, Division of Gender, Sexuality, and Health, New York Psychiatric Institute and Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, USA.

References

- Borell LN, Jacobs DR, Jr, Williams DR, Pletcher MJ, Houston TK, Kiefe CI. Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Adults Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;166:1068–1079. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos HMW, Van Beusekom G, Sandfort TGM. Sexual attraction and psychological adjustment in Dutch adolescents: Coping as a mediator. Archives Sexual Behavior. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0308-0. published online: June 18th 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Fisher LB, Austin B. Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents: findings from the Growing Up Today Study. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Delva J, Takeuchi D. Relationships between self-reported unfair treatment and prescription medication use, illicit drug use, and alcohol dependence among Filipino Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:933–940. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, Dunlap S. Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: a meta-analysis. Prevention Science. 2014;15:350–363. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Discrimination and alcohol-related problems among college students: A prospective examination of mediating effects. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2011;115:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Eliason M. Coming-out process related to substance use among gay, lesbian and bisexual teens. The Brown University Digest of Addiction Theory & Application. 2002;24:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Kuntsche S. Development and validation of the Drinking Motive Questionnaire Revised Short Form (DMQ–R SF) Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:899–908. doi: 10.1080/15374410903258967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychological Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ. The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1946–1952. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline AC, Jager J, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent risk factors for adult alcohol use and abuse: Stability and change of predictive value across early and middle adulthood. Addiction. 2008;103(Suppl 1):84–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Johnson LD, Bachman JG. Adolescents’ reported reasons for alcohol and marijuana use as predictors of substance use and problems in adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:106–116. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior research methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Gwadz M. Gay-related stress and emotional distress among gay, lesbian and bisexual youths: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:967–975. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Zarret NR. Mental health during emerging adulthood: Conformity and discontinuity in courses, causes, and functions. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. 2006. pp. 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Anticipating problem alcohol use developmentally from childhood into middle adulthood: What have we learned? Addiction. 2008;103(Suppl 1):100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]