Abstract

Strategies to enhance survival and direct the differentiation of stem cells in vivo following transplantation in tissue repair site are critical to realizing the potential of stem cell-based therapies. Here we demonstrated an effective approach to promote neuronal differentiation and maturation of human fetal tissue-derived neural stem cells (hNSCs) in a brain lesion site of a rat traumatic brain injury model using biodegradable nanoparticle-mediated transfection method to deliver key transcriptional factor neurogenin-2 to hNSCs when transplanted with a tailored hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel, generating larger number of more mature neurons engrafted to the host brain tissue than non-transfected cells. The nanoparticle-mediated transcription activation method together with an HA hydrogel delivery matrix provides a translatable approach for stem cell-based regenerative therapy.

Keywords: nanoparticles, transfection, neurogenin-2, neuronal differentiation, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) remains one of the most severe public health problems in terms of mortality, morbidity, and cost to the society. Cell dysfunction and low neural regenerative capabilities at the TBI site lead to the formation of a lesion cavity that is associated with prolonged neurological impairment [1]. Transplantation of neural stem or progenitor cells (NSCs) represents a promising strategy to reconstruct the lesion cavity and promote tissue regeneration. However, the lack of supportive tissue structure and vasculature within the cavity present a unfavorable environment that results in limited cell survival and poor control over differentiation and engraftment of transplanted cells [2–4]. Moreover, control over cell differentiation and maturation following transplantation remains a major challenge for stem cell-based therapy, as stem cells display a tendency to either maintain an undifferentiated phenotype or undergo uncontrolled differentiation at the lesion site.

The stem cell fate decision can be regulated by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors [5, 6]. Current methods of directed differentiation require extended exposure of NSCs to growth factors and small molecules; therefore they are difficult to implement for transplanted cells in vivo [7]. When compared to extrinsic factors, fate specification of stem cells can be more effectively regulated by the intrinsic factors through manipulation of the cell transcriptional network. Several such approaches have been successfully developed for cellular re-programming by resetting the transcriptional network using small molecules and delivery of mRNAs or transcription factors. In NSCs, the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors, such as neurogenin-2 (Ngn2), Mash1, and NeuroD, promote neuronal differentiation while suppressing astrocytic fate choice [8]. Recently it has been shown that transduction of human embryonic stem cell (ESC)-derived NSCs with Ngn2, Mash1, or NeuroD using adenoviruses induced rapid and efficient production of functional motor neurons in vitro [9, 10]. Although viral vector-mediated transfection methods have been shown to effectively deliver bHLH transcription factors to NSCs to direct neuronal differentiation, from the clinical translation perspective, non-viral transfection methods are preferred due to the concern of viral vectors with the insertional mutagenesis and particularly the reactivation of the reprogramming factors leading to tumor formation; more importantly, prolonged expression of exogenous transcription factors may adversely affect maturation and function of the differentiated cell types.

Numerous biomaterials have been studied as potential non-viral gene delivery vectors that are comparatively easier to manufacture and scale-up than viral vectors, although they are less efficienct in mediating transgene expression [11–14]. One particularly interesting class of polymeric gene carriers are poly (β-amino ester)s (PBAEs) due to their biodegradability via hydrolytically degradable ester linkages in the backbone, low cytotoxicity, and structural versatility [15–17]. PBAEs can effectively condense plasmid DNA forming nanoparticles with high level of transfection activities in several stem cell types [18–23]. Here we report a successful approach to promote neuronal differentiation of human fetal tissue-derived NSCs following transplantation to a brain lesion site in a rat TBI model, using PBAE-based nanoparticle transfection method to introduce transcriptional factor Ngn2 into hNSCs.

Results and Discussion

Highly Effective PBAE-based Nanoparticle-mediated Transfection of hNSCs

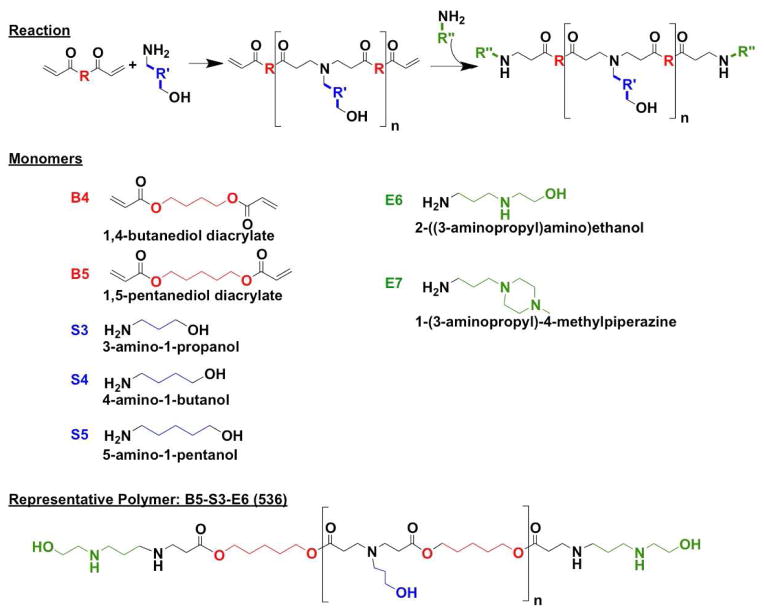

A series of PBAEs was synthesized following a method that we have previously described [17, 19] using the monomers and the reaction scheme shown in Scheme 1. Polymers were then named according to the backbone, side-chain, and end-cap monomers used in synthesis. As an example, the polymer made from base monomer B5, side chain S3, and end-cap E6 is referred to as 536.

Scheme 1.

Monomers and reaction scheme used to synthesize PBAE library. One backbone monomer (B) was polymerized with one side chain monomer (S). The diacrylate B-S base polymer was then terminated with one end-capping monomer (E).

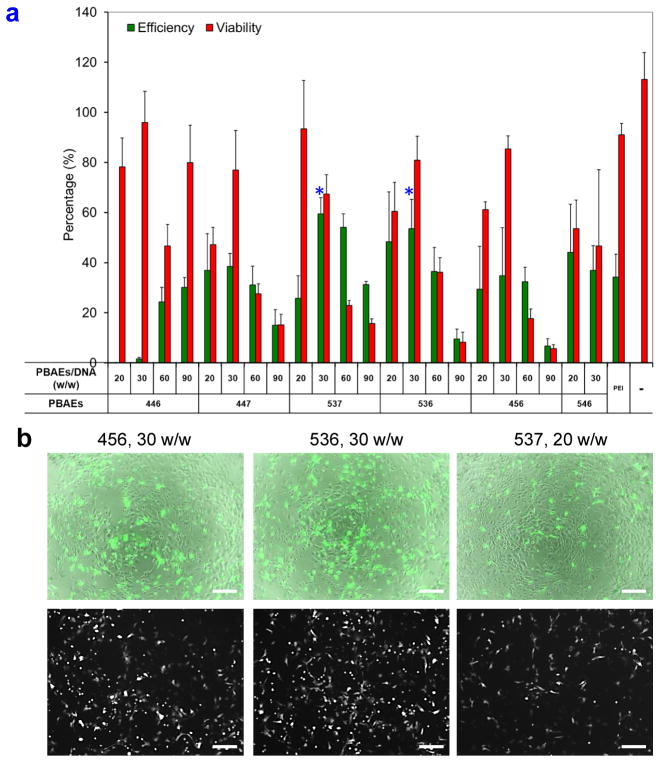

We first performed a screening experiment using this series of PBAE carriers to identify the optimal transfection conditions that yield high level of transgene expression and low cytotoxicity for hNSCs using EGFP as a reporter gene. Initial screens used an EGFP plasmid DNA dose of 2 μg/cm2 for all the conditions and a selected range of PBAE/EGFP plasmid DNA ratios (20, 30, 60, and 90 w/w) in order to identify top polymers from a group consisting PBAE 446, 447, 456, 536, 537, and 546 for further optimization (Figure 1a). Among these, PBAE 456, 536, and 537 at polymer/DNA ratios of 30, 30, and 20 w/w, respectively, showed higher transfection efficiencies and lower cytotoxicities compared with other PBAEs (Figure 1b). Based on these results, the next screening focused on PBAE 456, 536, and 537 carriers at a narrower range of PBAE/DNA ratios (10, 20, 30, 40, and 60 w/w) and two DNA transfection doses (1 and 2 μg/cm2) (Figure 2a). One of the top carriers, PBAE 536, at polymer/DNA ratio of 20 w/w and DNA dose of 1 μg/cm2 yielded a transfection efficiency of 35.6 ± 1.9% with a high cell viability of 91.9 ± 1.4% relative to non-transfected cells. The EGFP expression lasted for at least 10 – 14 days showing no significant decrease in viability (Figure S1, Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

Identification of nanoparticle-mediated transfection conditions with high transfection efficiencies and low cytotoxicities. (a) Initial screening used a DNA dose of 2 μg/cm2 for all conditions and an abbreviated range of PBAE/EGFP plasmid DNA ratios (20, 30, 60, and 90 w/w) in order to identify top polymers among 446, 447, 537, 536, 456, and 546 for further optimization based on their transfection efficiencies and cytotoxicities. * P < 0.05 superior to linear PEI (N/P=6). (b) GFP expression at day 2 of the tested PBAEs 456, 536, and 537 at polymer/DNA ratios of 30, 30, and 20 w/w, respectively, showed high transfection while causing low toxicity. In both sets of images, bright field and GFP were merged on the top and GFP only was shown on the bottom. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 2.

Establishment of a highly effective, cell-compatible, PBAEs-based nanoparticle-mediated transfection method for hNSCs using EGFP as a reporter gene. (a) Nanoparticle compositions, including top PBAE structures (456, 536, and 537), polymer/EGFP plasmid DNA ratios (10, 20, 30, 40, and 60 w/w), and DNA doses (1 and 2 μg/cm2) were screened for their transfection efficiencies and cytotoxicities. (b) EGFP expression efficiencies and viabilities of hNSCs at day 10 after transfection with different PBAE (536, 537, and 456) carriers at the polymer/DNA ratio of 20 w/w and the DNA dose of 1 μg/cm2 with three transfections on days 1, 4, and 9. One-min treatment with 25% DMSO increased the transfection efficacies with no significantly increased toxicity (n=4; *P < 0.05). (c) EGFP expression in hNSCs on day 10 after multiple transfections with PBAE 536 at the polymer/DNA ratio of 20 w/w and DNA dose of 1 μg/cm2 with or without DMSO treatment. Fluorescence microscopy showed that with the DMSO treatment, the average intensity of EGFP expression per cell also increased with improvements in the percentage of cells transfected. Scale bar = 100 μm.

We further tested the effects of multiple rounds of transfection and treatment with a buffer containing 25% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) on the transfection efficiency and gene expression duration. Our previous study demonstrated that a brief treatment (1 min) with a buffer containing 20–35% DMSO promoted linear polyethyleneimine (PEI)-based nanoparticle uptake and then enhanced its transfection efficiency [24–26]. The metabolic activity of the transfected cells was not significantly influenced when DMSO concentration was below 25%. In this study, when cells were transfected three times over the course of 10 days, transfection efficiency measured at day 10 after the initial transfection increased markedly with minimal loss in viability (Figure 2b). Transfections with PBAE 536, at polymer/DNA ratio of 20 w/w and DNA dose of 1 μg/cm2, showed a 10-day efficacy of 29.4 ± 2.1% with a single transfection, which was improved to 46.6 ± 3.7% and 64.8 ± 2.6% after two and three rounds of transfection, respectively, with no significant decrease in cell viability. Furthermore, with 25% DMSO treatment (1 min), those transfection efficacies increased to 34.6 ± 6.0%, 62.7 ± 3.6%, and 82.7 ± 2.5%, respectively, again with no significant decrease in cell viability. The average EGFP signal intensity increased along with improvements in the percentage of cells transfected (Figure 2c). In comparison to linear PEI (N/P=6), PBAE 536 has shown significantly higher transfection efficacy at day 10 (82.7 ± 2.5% as opposed to 16.5 ± 5.1%). We have chosen PBAE 536 at polymer/DNA ratio of 20 w/w and DNA dose of 1 μg/cm2 for following studies to deliver transcription factor genes, aided by 1 min of 25% DMSO treatment and 2 rounds of transfection over a 10-day duration.

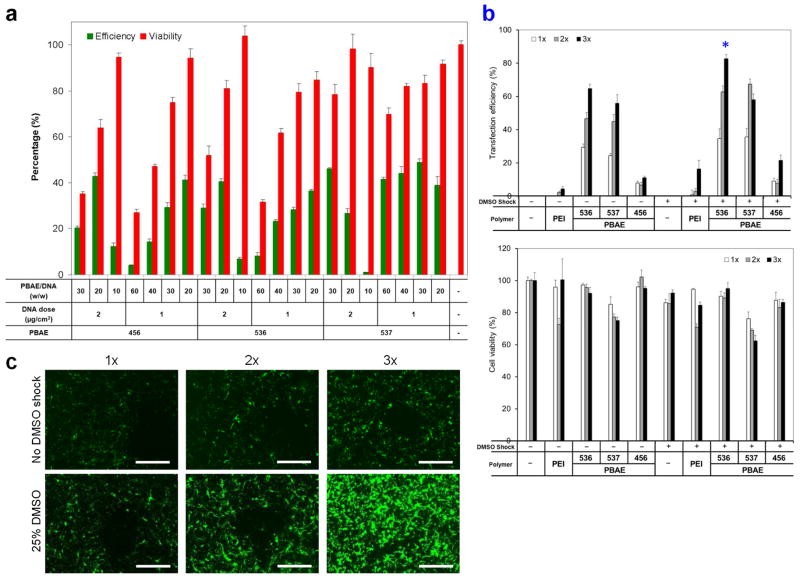

Enhanced Neuronal Differentiation of hNSCs by Nanoparticle-mediated Ngn2 Expression in Vitro

Using the optimized transfection condition identified above, we successfully delivered transcriptional factors Ngn2 and Mash1 into hNSCs with the efficiencies of 52.3 ± 2.6% and 45.5 ± 4.6%, respectively (Figure 3a). Co-delivery of Ngn2 and Mash1 was also shown to be highly feasible through incorporation of multiple plasmids into a single dose of PBAE nanoparticles (Figure 3a). We next examined the effect of nanoparticle-mediated Ngn2 expression on hNSC differentiation efficiency. Ngn2-transfected NSCs migrated and assembled into small compact clusters, which is a typical feature of in vitro neuronal differentiation (Figure 3b) [27]. Such a characteristic cluster shape was not apparent in the non-transfected cells. Ngn2-expressing hNSCs produced a larger number of neurons compared with non-transfected cells (Figure 3b, Tuj1+ cells: 33.8 ± 8.1% as opposed to 7.7 ± 0.6%; MAP2+: 29.6 ± 4.4% vs. 4.9 ± 0.7%) on day 10. Western blot analysis also confirmed that Ngn2-transfected cells expressed higher levels of Tuj1 and MAP2 compared to non-transfected cells (Figure 3c, Tuj1: 0.88 ± 0.9 as opposed to 0.57 ± 0.6; MAP2: 0.21 ± 0.2 vs. 0.05 ± 0.01; n = 3; P < 0.05). These results indicate PBAEs-based nanoparticle-mediated expression of Ngn2 in hNSCs effectively promoted neuronal differentiation, consistent with previous results obtained by viral vector-mediated transduction [8, 27].

Figure 3.

Effect of nanoparticle-mediated transcription factor expression on hNSC behaviors in vitro. (a) Neurogenin-2 (Ngn2) or Mash1 expression in hNSCs after transfection with PBAE 536 nanoparticles containing plasmids encoding Ngn2 or Mash1 at the polymer/DNA ratio of 20 w/w and the DNA dose of 1 μg/cm2 at day 2. Ngn2 and Mash1 could be co-expressed in hNSCs after transfection with PBAE 536 nanoparticles containing the mixture of these two plasmids encoding Ngn2 or Mash1, respectively, at the polymer/DNA ratio of 20 w/w and the DNA dose of 1 μg/cm2 (0.5 μg/cm2 Ngn2 and 0.5 μg/cm2 Mash1, respectively) at day 2. (b) Differentiation of hNSCs at day 10 after transfection with PBAE 536 nanoparticles containing plasmid encoding Ngn2 with two transfections on days 1 and 4. Cells were stained with DAPI (blue), GFAP (green), Tuj1 (red) and MAP2 (red), respectively. (c) Western blot analysis confirmed Ngn2-transfected hNSCs expressed higher levels of Tuj1 and MAP2 compared to non-transfected cells on day 10 (n = 3; *P < 0.05). (d) Ngn2-transfected hNSC spheroids in the optimized hyaluronic acid hydrogel generated more organized and thicker axon-like neurites than non-transfected cells on day 21. Scale bar = 100 μm. e) Proliferation of transfected hNSCs was inspected by alamarBlue kit on days 2, 5, 7, and 10 (n = 12; *P < 0.05).

In addition, we have inspected the effect of a single transfection on the cell differentiation on day 10 (Figure S2, Supportining Information). We found a larger number of Tuj1+ neurons were generated from Ngn2-transfected cells compared to non-transfected cells. Meanwhile, a lower number of GFAP+ astrocytes were detected in the Ngn2-transfected group. When compared with two-round transfection, one-round transfection led to a lower number of neurons (Tuj1+: 12.5 ± 1.9% as opposed to 33.8 ± 8.1%; MAP2+: 2.5 ± 0.8% as opposed to 14.8 ± 4.4%) in the Ngn2-transfected group (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Furthermore, we have also investigated cell differentiation after transfection with Mash1 or the combination of Ngn2 and Mash1. We could not detect significant difference among these three groups of Ngn2, Mash1, and the combination of Ngn2 and Mash1 in terms of Tuj1+ or MAP2+ neurons on day 10 following transfection (Figure S3, Supporting Information).

Recently we have demonstrated that a hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel with optimized pore size and cell adhesion cues can provide permissive microenvironment for transplanted stem cells to repopulate the lesion cavity leading to significant improvement in tissue regeneration following traumatic injury induced by controlled cortical impact (CCI)[28, 29]. In this study, we transplanted Ngn2-transfected hNSCs with our tailored HA hydrogel into the lesion site of CCI injury in a rat model. In addition, we used NSC spheroids rather than single cells for in vivo transplantation. The cells in spheroids have been shown to exhibit faster proliferation than single cells in cultures, and their differentiation more closely resembles that seen in vivo [30, 31]. Our previous studies have also demonstrated enhanced survival of NSCs following transplantation in the form of spheroids in comparison with single cells [31]. Here we generated spheroids from the transfected hNSCs with uniform and controllable size using agarose microwell culture using a protocol that we reported previously (Figure S4, Supporting Information)[31]. In vitro, Ngn2-expressing cell spheroids, encapsulated inside the tailored HA hydrogel, generated more organized and thicker axon-like neurites than non-transfected cells, indicative of robust neuronal differentiation (Figures 3d and S5 Supporting Information, 5.3 ± 0.6 μm as opposed to 1.0 ± 0.2 μm; n = 80; P < 0.05)[32]. In addition, we investigated the effect of Ngn2 expression on hNSC proliferation using the alamarBlue assay (Figure 3e). Compared with the non-transfected cells, Ngn2-expressing cells exhibited significantly decreased proliferation rates measured on days 2, 5, 7, and 10 (n = 4; P < 0.05). These findings are consistent with previous reports showing Ngn2-transduction in NSCs promoted cell cycle exit and inhibited their proliferation [27].

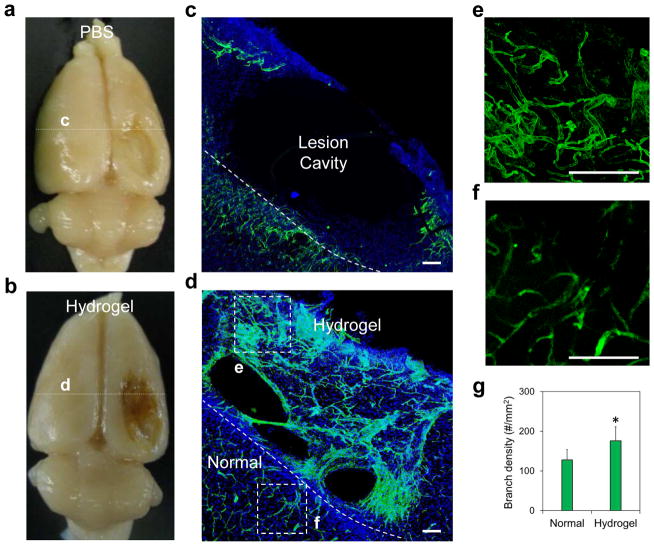

Vascular Network Formation at the CCI Lesion Site

Based on these findings, we generated hNSC spheroids at 2 days after transfection by a hydrogel microwell culture, and then transplanted them with our tailored in situ forming HA hydrogel into CCI lesion site. With sham treatment (PBS injection), the CCI model generated a large lesion cavity by week 4 (~10 mm × 6 mm × 2.5 mm) that encompassed the cerebral cortex and striatum on the injured side of the brain due to profound loss of parenchyma (Figure 4a, c). In contrast, the tailored HA hydrogel, when injected on day 3 after the CCI injury, promoted significant vasculature formation at the lesion site at 4 weeks following injection (Figures 4b, d and S6, Supporting Information, Reca-1+ for endothelial cells). This improved angiogenesis was attributed to the ability of this hydrogel to stabilize the post-injury environment, allowing host cell to infiltrate and migrate inside its matrix, and retain tissue-secreted growth factors, particularly vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as we reported before [33]. Quantitative analysis of the newly regenerated microvascular network within the injected hydrogels at the lesion site indicated a higher blood vessel density (total number of vessels/area) relative to that in the surrounding host tissue (Figure 4e–g, 176 ± 35/mm2 as opposed to 128 ± 26/mm2; n = 3; P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Brain tissue regeneration in the controlled cortical impact lesion site mediated by a tailored hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel. (a–d) Examination of brain tissue regeneration after treatment with (a, c) PBS and (b, d) tailored HA hydrogel. (d, e) Revascularization (Reca-1+ for blood vessels with green) was revealed at week 4 after hydrogel injection across the whole lesion. DAPI was stained for cell nuclei with blue. (f) Blood vessels at the normal tissue close to the lesion site. Scale bar = 100 μm. (g) Quantitative analysis of the branching density. The regenerated blood vessels had statistically significantly higher branching density than those in the surrounding normal brain (n = 3; *P < 0.05).

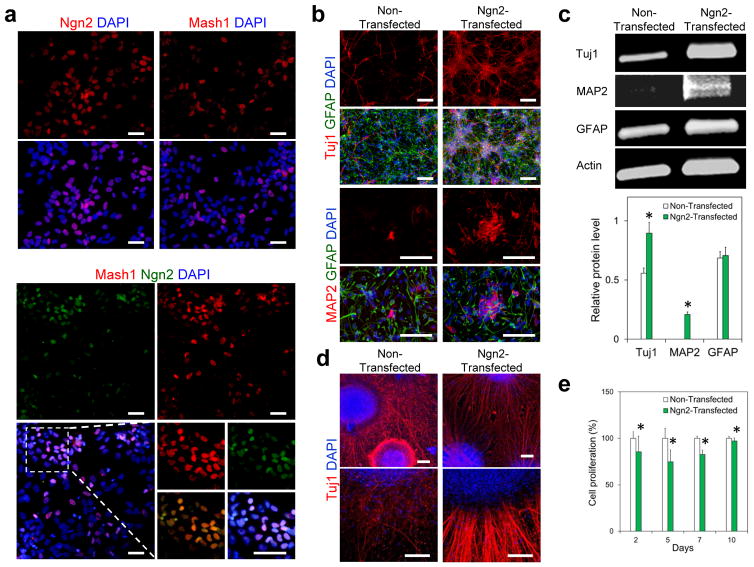

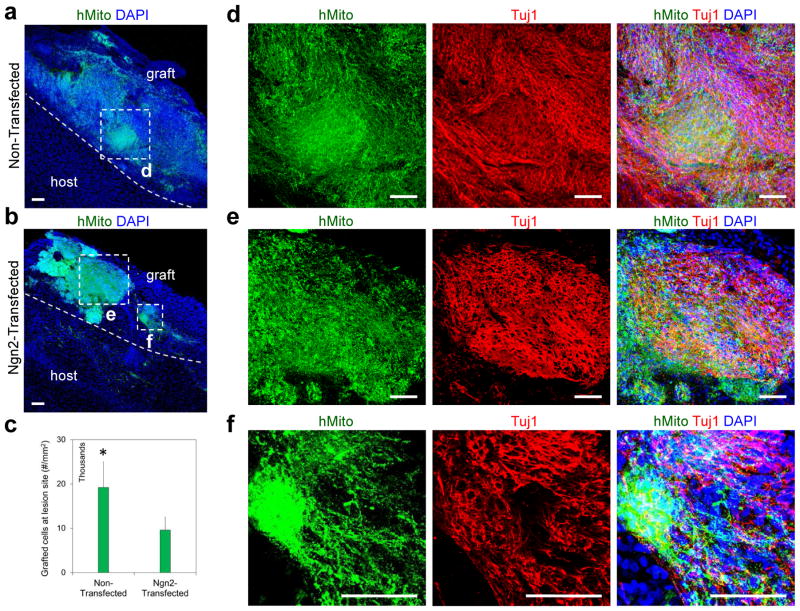

Survival and Differentiation of Ngn2-transfected hNSCs at the Brain Lesion Site

We found a large number of hNSCs that survived and populated the CCI lesion site at 4 weeks post transplantation in the form of spheroids with our tailored HA hydrogel [Figure 5a, b, human mitochondria (hmito)+]. A significantly larger number of grafted cells were identified in the group of non-transfected cells compared with Ngn2-transfected cells (Figure 5c, 19,200 ± 3,840/mm2 as opposed to 9,600 ± 300/mm2, n = 3; P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Survival and neuronal differentiation of transplanted hNSCs at a controlled cortical impact lesion site in rat brain. (a, b) Large number of human cells [human mitochondria (hMito)+, green] were identified at the lesion site after transplantation with tailored HA hydrogel in the format of spheroid. DAPI was stained for cell nuclei with blue. Transplanted cells still maintatined the spheroid structure in both non-transfected cells and Ngn2-transfected cells. (c) Quantitative analysis has shown a larger number of transplanted cells were identified at the CCI lesion site in the group of non-transfected cells compared to Ngn2-transfected cells (n = 3; *P < 0.05). (d–f) A remarkably high level of the engrafted hNSCs (hMito+, green) in both Ngn2-transfected and non-transfected groups differentiated into Tuj1+ (red) neuronal lineage at the repair site. Scale bar = 100 μm.

We next examined the differentiation efficiency of the engrafted hNSCs at the brain lesion site. We found that a remarkably high level (> 80%) of hNSCs in both non-transfected and Ngn2-transfected groups differentiated into Tuj1+ neuronal lineage at the repair site (Figures 5d–f, and S7, Supporting Information). Recently Lu et al. used a fibrin hydrogel loaded with a cocktail of 9 growth factors to deliver human fetal spinal cord-derived or induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived NSCs into a transected spinal cord injury site. They verified that a large number of these two types of cells grafted and differentiated into mature neurons efficiently (NeuN+, 57 ± 1.7% and 71.2 ± 3.1%, respectively) with axons extending over millimeter distances in the injured spinal cord. The improved neuronal differentiation from transplanted hNSCs were attributed to these co-delivered neurogenic growth factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF). In our study, we did not pre-load any exogenous growth factors into the HA hydrogel matrix. The biased neuronal differentiation of transplanted hNSCs is mediated primarily by intrinsic factors from the host tissue. As shown in Figure 6a, regenerated blood vessels (Reca-1+) grew into and distributed throughout the lesion site, and some of them also penetrated into transplanted spheroids. The regenerated blood vessel network may have facilitated the delivery of endogenous neurogenic factors, such as nerve growth factor, which is up-regulated in repair site of the brain tissue and may induce neuronal differentiation [34, 35].

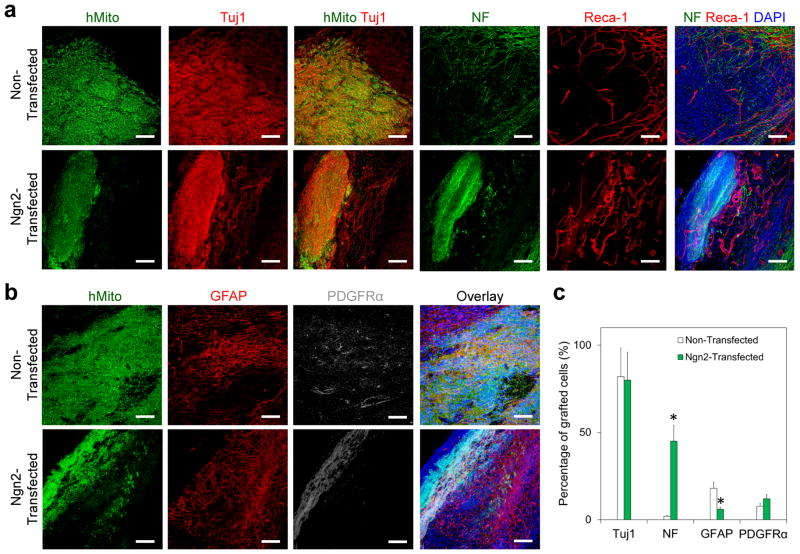

Figure 6.

Mature neuron derived from transplanted Ngn2-transfected hNSCs at the brain lesion site. (a, b) Immunofluorescence staining confirmed the differentiation of transplanted hNSCs into (a) neurons [Tuj1+ and neurofilament (NF)+, red] and (b) glial cells (GFAP+, red, and PDGFRα+, gray) at 4 weeks after transplantation with our tailored HA hydrogel. Transplanted cells were identified by human mitochondria with green. DAPI was stained for cell nuclei with blue. (c) Quantitative analysis of differentiation of transplanted hNSCs at the lesion site. Ngn2-transfected hNSCs generated significantly more mature neurons (NF+) and less astrocytes (GFAP+) than non-transfected cells at the lesion site at 4 weeks after transplantation (n = 3; *P < 0.05). Scale bar = 100 μm.

When compared to non-transfected hNSCs, Ngn2-transfected hNSCs generated a significantly larger number of neurofilament positive (NF+) neurons at the lesion site [Figures 6a, c, and S8a, Supporting Information, 45.6 ± 9.1% as opposed to 2.0 ± 1.6%; n = 3; P < 0.05] at 4 weeks post transplantation, implying that the transcription activation through nanoparticle-mediated expression of Ngn2 was effective in enhancing neuronal maturation in vivo. Correspondingly, fewer Ngn2-transfected cells differentiated into astrocytes compared with non-transfected cells (Figures 6b, c, and S8b, Supporting Information): 6.0±3.6% vs. 15.5±2.5% (n = 3; P < 0.05) of the engrafted cells expressed GFAP at week 4 in groups received Ngn2-transfected and non-transfected hNSCs, respectively. No significant difference was observed between Ngn2-transfected and non-transfected cells in terms of the percentage of PGDFRα+ oligodendrocyte progenitors (12.0 ± 2.4% vs. 7.8 ± 1.8%) among the engrafted cells. These results demonstrate that this transcriptional modification induced by these biodegradable PBAE/DNA nanoparticle-mediated transfection can effectively direct neuronal maturation of human NSCs in vivo [36, 37]. More importantly, this is the first demonstration of robust survival and neuronal differentiation of the transplanted hNSCs in a CCI site, whereas the transplanted neural stem/progenitor cells are transcriptionally activated. The neuronal differentiation efficiency is comparable to those obtained with rat NSCs transduced with retroviruses expressing Ngn2 (about 56% NeuN+ neurons engrafted at 8 weeks) following transplantation in a normal adult rat brain [27].

Conclusions

Taken together, we have established a PBAE-based nanoparticle system to deliver Ngn2 to human fetal tissue-derived NSCs to promote neuronal differentiation and maturation in a brain tissue repair site. A larger number of Ngn2-transfected hNSCs, when transplanted with a tailored HA hydrogel into the TBI lesion site in a rat model, more effectively differentiated into neuronal lineage compared with non-transfected cells. Our further studies will focus on clarifying in details the specific subtypes of these neurons, their integration with host tissue and their capacity to induce behavioral improvements in the animal model of TBI. Given that previous study showed efficient neuronal maturation and integration into host dentate gyrus of normal adult rats by virus-transduced neural progeniors with Ngn2[38], and the fact that an extensive vascular support was generated in the lesion site around the transplanted cells in our model, we anticipate a high level of integration of these differentiated cells in the regenerated tissue in a longer term study. Our study identifies the suitable nanoparticle system to achieve effective transcription activation of hNSCs. Together with our tailored HA hydrogel delivery matrix, it offers a translatable approach to control their neuronal differentiation and maturation in a brain lesion repair site, and thus improving the therapeutic outcomes of stem cell-based therapy.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Homo sapiens neurogenin-2 (Ngn2, pCMV6 vector, SC322602) and achaete-scute complex homolog 1 (Mash1, pCMV6 vector, SC117427) as transfection-ready DNAs were obtained from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD). pEGFP-N1 DNA was obtained from Elim Biopharmaceuticals (Hayward, CA). Recombinant fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Accutase was from Innovative Cell Technologies (San Diego, CA). Mouse laminin was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), and 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI) was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Primary antibodies used in this study are shown in Table S1. Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA).

Monomers used for synthesizing polymers (Scheme 1) were obtained as follows: 1,4-butanediol diacrylate (B4; Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA), 1,5-pentanediol diacrylate (B5; Monomer-Polymer and Dajac Labs, Trevose, PA), 3-amino-1-propanol (S3; Alfa Aesar), 4-amino-1-butanol (S4; Alfa Aesar), 5-amino-1-pentanol (S5; Alfa Aesar), 2-(3-aminopropylamino) ethanol (E6; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 1-(3-aminopropyl)-4-methylpiperazine (E7; Alfa Aesar). All other chemical reagents were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Polymer Synthesis

Poly (β-amino ester)s (PBAEs) were synthesized in a two-step reaction as described previously using small commercially-available molecules (Figure 1)[18]. Briefly, for each polymer, one backbone monomer (labeled as B4, B5, or B6) was mixed with a side-chain monomer (S3, S4, or S5), either neat or as a 500 mg/mL solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), at a 1.1:1 or 1.2:1 ratio of B:S. The mixture was stirred at 90°C for 24 h to yield acrylate-terminated base polymers by Michael addition. Base polymers were end-capped with a small molecule (E6 or E7) by dissolving end-capping molecules in DMSO (167 mg/mL) and adding 480 μL end-capping solutions to 320 μL of 0.5 M base polymer in DMSO, then shaking the mixture at room temperature overnight. Final polymers were stored with desiccant at 4°C as 100 mg/mL solutions in DMSO. Polymers used for optimization experiments were stored in small aliquots at −20°C to minimize freeze–thaw of samples. For the remainder of this report, PBAEs are named according to their component monomers in the format “BSE” along with the B:S synthesis ratio used. For example, B5 polymerized with S3 at 1.1:1 ratio and end-capped with E6 is called “536, 1.1:1.”

Cell Culture

Human neural stem/progenitor cells (hNSCs) were obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA). The cells were derived from the ventral mesencephalon region of human fetal brain and immortalized by retroviral transduction with the v-myc oncogene. In conventional culture, laminin (20 μg/mL) was used to coat tissue culture plastic-wares at least 4 h before hNSC seeding. Human NSCs were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 and used before passage 5 in this study. Human NSCs were maintained in ReNcell Neural Stem Cell Medium (Millipore) with FGF-2 (20 ng/mL) and EGF (20 ng/mL). For differentiation study, hNSCs were cultured in the medium without FGF-2 and EGF.

Amplification and Purification of Plasmid DNAs

Plasmids encoding Ngn2 or Mash1 were amplified in Escherichia coli DH5α and purified by an endotoxin free Giga plasmid purification kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified DNA was dissolved in UltraPure DNase/RNase-free distilled water, and its concentration was determined by UV absorbance at 260 and 280 nm.

Cell Transfection and Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) Treatment

Nanoparticle compositions, including PBAE structures (446, 447, 456, 536, 537, and 546), polymer/plasmid DNA ratios (10, 20, 30, 40, 60, and 90 w/w), and DNA doses (1 and 2 μg/cm2) were screened for their transfection efficiencies and cytotoxicities through EGFP plasmid DNA. Briefly, before transfections, hNSCs were seeded into flat-bottom, tissue culture treated 96-well plates (1.5 × 104 cells/well, 100 μL medium/well). Cells were allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. Plasmid DNA coding EGFP was diluted in 25 mM sodium acetate buffer (NaAc, pH 5). PBAEs were diluted into the NaAc buffer and then mixed with the DNA solution at various PBAE/DNA mass ratios (w/w). After allowing 10 min for self-assembly, the nanoparticles were added directly to the cells at a 1:5 ratio (v/v) of particles to media. The final dosage was 300 and 600 ng of DNA added per well (1 and 2 μg/cm2). Each group contained 4 replicates. After 2 h incubation at 37°C, the media and particles were removed and replaced with fresh culture medium.

In order to further improve transgene expression, PBAE conditions with very low toxicity but good-to-moderate transfection efficiencies were repeated with DMSO shock. For this, transfections were carried out as described above. After particles are removed following a 2 h incubation, cells were washed for 1 min with medium containing either 0% or 25% DMSO before replacing all liquid with fresh culture medium. In case of multiple transfections, the second and third transfections with the same protocol were performed at days 4 and 9, respectively.

Transfection Efficiency

EGFP expression was measured at 48 h after transfection using a flow cytometry (Accuri C6, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with Hypercyt high-throughput robotic sampler (Intellicyt, Albuquerque, NM). Cells were transferred to round-bottom 96-well plates. Transfection data were analyzed with FlowJo7 software (Treestar).

Cell Viability and Proliferation

Cytotoxicity of PBAEs/DNA nanoparticles were determined by WST-1 dye reduction assay at 24 h after cell transfection. The medium in each well was replaced with 100 μL of fresh complete medium containing 10 μL of WST-1 reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The absorbance of the supernatant at 450 nm (using 600 nm as a reference wavelength) was measured on a microplate reader (Infinite M200, TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). AlamarBlue assay was conducted to characterize cell proliferation according to the manufacture’s protocol.

Cell Differentiation

The differentiation of hNSCs at day 10 after transfection with nanoparticles containing plasmids encoding Ngn2 or GFP was evaluated by immunocytochemistry. The cells were fixed and stained with primary antibodies, Tuj1, GFAP, and MAP2. The cells were further stained with fluorophore conjugated secondary antibodies. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. The cells were imaged using the fluorescence microscope. At least 6 random fields per sample were analyzed.

Western blot was also applied to investigate these differentiated cells. Whole-cell extracts were prepared using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors and then centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet the cell debris. The protein extracts were quantitated by BCA assay, resolved by SDS-PAGE on 4–12% Bis–Tris gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blotted with Tuj1, GFAP, MAP2 and actin antibodies, detected using IRDye 800CW and IRDye 680LT secondary antibodies and, visualized by a near-infrared fluorescence scanner (Odyssey, Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Three-dimensional (3D) Cell Culture in Hydrogels

Spheroids of Ngn2-transfected or non-transfected cells with a uniform diameter of 200 μm were prepared, respectively, as we described before [31]. We have also developed and optimized hyaluronic acid (HA) based-hydrogels for 3D culture of NSC spheroids [28]. To avoid spheroid precipitating onto the surface of plate during the hydrogel formation, we coated the plate with hydrogels overnight then mixed NSC spheroids with hydrogel precursor solutions and seeded on the top of pre-formed hydrogels. Cells were cultured for 21 days and assayed for their differentiation.

Traumatic Brain injury (TBI) Model and Cell Transplantation

The controlled cortical impact (CCI) model was applied as previously described [39]. In brief, unilateral contusions of the right frontoparietal cortex were induced using a CCI device, which has been shown to be a clinically relevant model of TBI [1]. Nude rats (weighing 200 – 300 g, Charles River Laboratories) were anaesthetized in an acrylic glass chamber with 5% isoflurane, incubated and ventilated with 2% isoflurane in a gas mixture (30% oxygen and 70% nitrogen), and fixed on a stereotaxic frame. After exposing the skull, an 8-mm craniectomy was made over the right frontoparietal cortex, with the lesion center 5 mm right to the center suture, midway between Bregma and Lambda. The CCI was produced with a 5-mm diameter pneumatically-operated metal impactor, which struck the brain at a velocity of 4.0 m/s to a depth of 2.5 mm below the dura mater, and remained in the brain for 400 ms. The impactor rod was angled 15° to the vertical to be perpendicular to the tangential plane of the brain curvature at the impact surface. A linear variable displacement transducer connected to the impactor recorded velocity and duration to verify insult consistency. After the CCI, the incision was sutured and the animals were placed on warm pads for recovery. All rats were housed in a temperature-controlled environment with a 12:12 h light–dark cycle, with food and water available.

All transplantations were performed 3 days post-surgery. Following induction of anesthesia, the previous incision was cut to expose the location of the impact. Transplantations were divided into four groups: phosphate buffered saline (PBS) only, HA hydrogels, hNSC spheroids with hydrogels, and Ngn2-transfected hNSC spheroids with hydrogels. One million cells were transplanted into each rat in the format of spheroids. Transplant components were kept on ice and mixed immediately prior to injection. Five points were selected in the lesion area for transplantation. Cells (20 μL/point) were delivered at a rate of 5 μL/min directly into the lesion using the same stereotactic coordinates as described above. The needle was left in place for an additional 2 min to prevent back-flow of cells. Following this, the incision was sutured and animals placed on warm pads for recovery. All surgical interventions and pre- and postsurgical care was provided in accordance with the PHS Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, 1996), and the guidelines provided by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU, Richmond, VA, AD10000757).

Tissue Processing and Immunohistochemistry

To evaluate hNSCs transplanted following TBI, animals were sacrificed at 4 weeks post transplantation. Animals were deep anesthetized in an acrylic glass chamber with 5% isoflurane and transcardially perfused with 300 mL of PBS followed by 300 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Each brain was immediately removed from the skull, the cerebellum and brainstem removed, and an 8-mm coronal section centered on the lesion made through both hemispheres using a brain slicer (Zivic Miller, Zelienople, PA). The coronal sections were post-fixed overnight at 4°C, and then transferred to 30% sucrose. Specimens were sectioned coronally with vibratome at a thickness of 100 μm and collected in PBS.

For immunostaining, sections were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 and blocked with 4% normal goat serum in PBS for 2 h. Primary antibodies in Table S1 were then applied for overnight at 4°C. Cy2 and cy3 affinity secondary antibodies, goat-anti-mouse and anti-rabbit were used at 1:400 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA). The specimens were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope.

In consideration of quantitative analysis of transplanted cell, for each brain section, six images were randomly taken from different regions. The percentage of positive cells in the population was calculated and compared between groups.

Statistical Analysis

Data are shown as mean ± S.D (Standarad Deviation). All statistical analyses were performed with the OriginPro 8.0 software package. Data were analyzed by one-way or two-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) followed by Tukey’s post-test and the t-test where appropriate. The values were considered significantly different at P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R21NS085714-01A1 to H.-Q. M. and R21NS078710-02 to D. S.), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (1R01EB016721 to J. J. G.), and the U.S. National Science Foundation Faculty Early Career Awards (CBET 1312970 to N.Z.). M.T. acknowledges partial support by fellowships from Stiftelsen Olle Engkvist Byggmästare, the Foundation Blanceflor Boncompagni-Ludovisi, née Bildt, and Hans Werthén fonden. X.-W. L. acknowledges a postdoctoral fellowship from the Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund (2013MSCRF-00042169).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

X.-W. L. contributed to the design, execution and analysis of the described in vitro and in vivo experiments and the preparation of the manuscript. S. T. contributed to the polymer synthesis and in vitro nanoparticle screening. X.-Y. L. contributed to the execution of the described in vivo experiments. M. T. contributed to the transfection screening studies and plasmid preparations. Y-H. C. contributed to the discussion of the in vitro studies. A. R. and D. S. contributed to the animal surgeries. J. G. contributed to the discussion and analysis of the in vitro studies. N. Z. and X.-J. W. contributed to the discussion and analysis of the in vivo studies. H.-Q. M. conceived the project, contributed to design and analysis of the study and preparation of the manuscript.

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Animal models of traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:128–42. doi: 10.1038/nrn3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delcroix GJR, Schiller PC, Benoit J-P, Montero-Menei CN. Adult cell therapy for brain neuronal damages and the role of tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2105–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hicks AU, Lappalainen RS, Narkilahti S, Suuronen R, Corbett D, Sivenius J, et al. Transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursor cells and enriched environment after cortical stroke in rats: cell survival and functional recovery. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:562–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hovakimyan M, Müller J, Wree A, Ortinau S, Rolfs A, Schmitt O. Survival of transplanted human neural stem cell line (ReNcell VM) into the rat brain with and without immunosuppression. Ann Anat. 2012;194:429–35. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aldskogius H, Berens C, Kanaykina N, Liakhovitskaia A, Medvinsky A, Sandelin M, et al. Regulation of boundary cap neural crest stem cell differentiation after transplantation. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1592–603. doi: 10.1002/stem.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pang ZP, Yang N, Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Fuentes DR, Yang TQ, et al. Induction of human neuronal cells by defined transcription factors. Nature. 2011;476:220–3. doi: 10.1038/nature10202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu M-L, Zang T, Zou Y, Chang JC, Gibson JR, Huber KM, et al. Small molecules enable neurogenin 2 to efficiently convert human fibroblasts into cholinergic neurons. Nat Commun. 2013:4. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nieto M, Schuurmans C, Britz O, Guillemot Fo. Neural bHLH genes control the neuronal versus glial fate decision in cortical progenitors. Neuron. 2001;29:401–13. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hester ME, Murtha MJ, Song S, Rao M, Miranda CJ, Meyer K, et al. Rapid and efficient generation of functional motor neurons from human pluripotent stem cells using gene delivered transcription factor codes. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1905–12. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jandial R, Singec I, Ames CP, Snyder EY. Genetic modification of neural stem cells. Mol Ther. 2008;16:450–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunshine JC, Bishop CJ, Green JJ. Advances in polymeric and inorganic vectors for nonviral nucleic acid delivery. Ther Deliv. 2011;2:493–521. doi: 10.4155/tde.11.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bharali DJ, Klejbor I, Stachowiak EK, Dutta P, Roy I, Kaur N, et al. Organically modified silica nanoparticles: a nonviral vector for in vivo gene delivery and expression in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11539–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504926102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tseng TC, Hsu SH. Substrate-mediated nanoparticle/gene delivery to MSC spheroids and their applications in peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomaterials. 2014;35:2630–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickard MR, Barraud P, Chari DM. The transfection of multipotent neural precursor/stem cell transplant populations with magnetic nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2274–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynn DM, Anderson DG, Putnam D, Langer R. Accelerated discovery of synthetic transfection vectors: parallel synthesis and screening of a degradable polymer library. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8155–6. doi: 10.1021/ja016288p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tzeng SY, Higgins LJ, Pomper MG, Green JJ. Biomaterial-mediated cancer-specific DNA delivery to liver cell cultures using synthetic poly(beta-amino ester)s. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101:1837–45. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tzeng SY, Green JJ. Subtle changes to polymer structure and degradation mechanism enable highly effective nanoparticles for siRNA and DNA delivery to human brain cancer. Adv Healthc Mater. 2013;2:468–80. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tzeng SY, Guerrero-Cázares H, Martinez EE, Sunshine JC, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Green JJ. Non-viral gene delivery nanoparticles based on Poly(beta-amino esters) for treatment of glioblastoma. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5402–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerrero-Cázares H, Tzeng SY, Young NP, Abutaleb AO, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Green JJ. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles show high efficacy and specificity at DNA delivery to human glioblastoma in vitro and invivo. ACS Nano. 2014;8:5141–53. doi: 10.1021/nn501197v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tzeng SY, Hung BP, Grayson WL, Green JJ. Cystamine-terminated poly(beta-amino ester)s for siRNA delivery to human mesenchymal stem cells and enhancement of osteogenic differentiation. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8142–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sunshine J, Green JJ, Mahon KP, Yang F, Eltoukhy AA, Nguyen DN, et al. Small-molecule end-groups of linear polymer determine cell-type gene-delivery efficacy. Adv Mater. 2009;21:4947–51. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nauta A, Seidel C, Deveza L, Montoro D, Grova M, Ko SH, et al. Adipose-derived stromal cells overexpressing vascular endothelial growth factor accelerate mouse excisional wound healing. Mol Ther. 2013;21:445–55. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang F, Green JJ, Dinio T, Keung L, Cho SW, Park H, et al. Gene delivery to human adult and embryonic cell-derived stem cells using biodegradable nanoparticulate polymeric vectors. Gene Ther. 2009;16:533–46. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawai S, Nishizawa M. New procedure for DNA transfection with polycation and dimethyl sulfoxide. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:1172–4. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.6.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaney WG, Howard DR, Pollard JW, Sallustio S, Stanley P. High-frequency transfection of CHO cells using polybrene. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1986;12:237–44. doi: 10.1007/BF01570782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tammia M, Ren Y, Liu X, Cashman CR, Mi R, Chung T, et al. DMSO shock yields highly efficient transient transfection by PEI/DNA nanoparticles. American Society for Gene and Cell Therapy; Philadelphia, PA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yi S-H, Jo AY, Park C-H, Koh H-C, Park R-H, Suh-Kim H, et al. Mash1 and Neurogenin 2 Enhance Survival and Differentiation of Neural Precursor Cells After Transplantation to Rat Brains via Distinct Modes of Action. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1873–82. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X, Liu X, Josey B, Chou CJ, Tan Y, Zhang N, et al. Short laminin peptide for improved neural stem cell growth. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3:662–70. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Liu X, Cui L, Brunson C, Zhao W, Bhat NR, et al. Engineering an in situ crosslinkable hydrogel for enhanced remyelination. The FASEB Journal. 2013;27:1127–36. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-211151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mothe AJ, Kulbatski I, Parr A, Mohareb M, Tator CH. Adult spinal cord stem/progenitor cells transplanted as neurospheres preferentially differentiate into oligodendrocytes in the adult rat spinal cord. Cell Transplant. 2008;17:735–51. doi: 10.3727/096368908786516756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Liu X, Tan Y, Tran V, Zhang N, Wen X. Improve the viability of transplanted neural cells with appropriate sized neurospheres coated with mesenchymal stem cells. Med Hypotheses. 2012;79:274–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng B, Gou X, Chen H, Li L, Zhong H, Xu H, et al. Targeted delivery of Neurogenin-2 protein in the treatment for cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8786–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, Zhang N, Wen X. Methods and compositions for cell culture platform. USA: Clemson University Research Foundation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeKosky ST, Taffe KM, Abrahamson EE, Dixon CE, Kochanek PM, Ikonomovic MD. Time course analysis of hippocampal nerve growth factor and antioxidant enzyme activity following lateral controlled cortical impact brain injury in the rat. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:491–500. doi: 10.1089/089771504774129838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johanson C, Stopa E, Baird A, Sharma H. Traumatic brain injury and recovery mechanisms: peptide modulation of periventricular neurogenic regions by the choroid plexus-CSF nexus. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:115–33. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0498-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montserrat N, Garreta E, González F, Gutiérrez J, Eguizábal C, Ramos V, et al. Simple generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells using poly-beta-amino esters as the non-viral gene delivery system. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12417–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.168013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez F, Barragan Monasterio M, Tiscornia G, Montserrat Pulido N, Vassena R, Batlle Morera L, et al. Generation of mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells by transient expression of a single nonviral polycistronic vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8918–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901471106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen X, Lepier A, Berninger B, Tolkovsky AM, Herbert J. Cultured subventricular zone progenitor cells transduced with Neurogenin-2 become mature glutamatergic neurons and integrate into the dentate gyrus. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dixon CE, Clifton GL, Lighthall JW, Yaghmai AA, Hayes RL. A controlled cortical impact model of traumatic brain injury in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;39:253–62. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.