Abstract

Polymerization of substrate-supported bilayers composed of dienoyl phosphatidylcholine (PC) lipids is known to greatly enhance their chemical and mechanical stability, however the effects of polymerization on membrane fluidity have not been investigated. Here planar supported lipid bilayers (PSLBs) composed of dienoyl PCs on glass substrates were examined to assess the degree to which UV-initiated polymerization affects lateral lipid mobility. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) was used to measure the diffusion coefficients (D) and mobile fractions of rhodamine-DOPE in unpolymerized and polymerized PSLBs composed of bis-sorbyl phosphatidylcholine (bis-SorbPC), mono-sorbyl phosphatidylcholine (mono-SorbPC), bis-dienoyl phosphatidylcholine (bis-DenPC) and mono-dienoyl phosphatidylcholine (mono-DenPC). Polymerization was performed in both the Lα and Lβ phase for each lipid. In all cases, polymerization reduced membrane fluidity, however measurable lateral diffusion was retained which is attributed to a low degree of polymerization. The D values for sorbyl lipids were less than those of the denoyl lipids; this may be a consequence of the distal location of polymerizable group in the sorbyl lipids which may facilitate inter-leaflet bonding. The D values measured after polymerization were 0.1 to 0.8 of those measured before polymerization, a range that corresponds to fluidity intermediate between that of a Lα phase and a Lβ phase. This D range is comparable to ratios of D values reported for liquid-disordered (Ld) and liquid-ordered (Lo) lipid phases, and indicates that the effect of UV polymerization on lateral diffusion in a dienoyl PSLB is similar to the transition from a Ld phase to a Lo phase. The partial retention of fluidity in UV polymerized PSLBs, their enhanced stability, and the activity of incorporated transmembrane proteins and peptides is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Artificial lipid membranes have been extensively studied, primarily due to their importance as models for natural cell membranes and their use as membrane-mimetic constructs in a variety of technological applications, including biocompatible coatings, therapeutic and diagnostic vehicles, and chemical and biological sensors.1–6 Creation of artificial membranes that provide a suitable environment for reconstitution of integral membrane proteins and peptides with retention of structure and bioactivity has been a very active area of research.7–13 Much of this work has focused on solid supported and suspended membranes because these constructs are compatible with many surface analytical/physical characterization techniques and biosensor transduction strategies. Both the chemically-specific properties of the lipid constituents (e.g., head group structure) as well as the lipid bilayer continuum properties (e.g., elasticity, curvature, thickness, fluidity) are thought to be important in determining if a reconstituted transmembrane protein is functional in an artificial lipid membrane.14–17

An additional consideration that is relevant for use of artificial membranes in technological applications is bilayer stability.18 Lipids self-organize into bilayers by non-covalent intermolecular forces that may be compromised by exposure to chemical conditions, thermal instability, and mechanical disruptions encountered during device use and storage.1,19–21 Numerous methods to stabilize lipid membranes have been investigated,11,18,22,23 including linear and cross-linking polymerization of lipid monomers.3–5,24–26

Synthetic lipids functionalized with reactive dienoyl groups have been used to create several types of poly(lipid) supramolecular assemblies, including vesicles, suspended planar membranes, and planar supported lipid bilayers (PSLBs).3,19,26–39 Numerous parameters, such as the chemical structure of the lipid, the polymerization method, and the type of supramolecular assembly, influence the degree to which polymerization alters bilayer properties. Remarkably enhanced membrane stability, altered permeability to ions and small molecules, changes in thermotropic behavior, and other important properties have been observed. Planar bilayers composed of polymerized dienoyl lipids also have been used as hosts for reconstitution of membrane proteins and peptides.31,32,36–38 A key question is how the polymerization conditions and the altered properties of the bilayer affect the incorporated protein or peptide. Subramaniam et al.37,38 reconstituted bovine rhodopsin (bRho) into dienoyl PSLBs that were subsequently polymerized using UV irradiation. bRho photoactivity was retained when the polymeric network was formed in the center of the bilayer but not when it was adjacent to the glycerol backbone, which was ascribed to differences in the effect of polymerization on bilayer bending rigidity.37,38 Alamethicin, an ion channel-forming peptide, loses activity in a UV polymerized dienoyl lipid bilayer; this finding was attributed to the lower fluidity of the poly(lipid) which inhibits peptide oligomerization.31 In a mixed bilayer composed of a poly(lipid) and a nonpolymerizable lipid, however, alamethicin channel activity increased after polymerization, presumably because the peptides were localized in the nonpolymerized, fluid lipid domains.

The effects of lipid polymerization on membrane fluidity, which is most frequently assessed by measuring the lateral diffusion coefficient (D) of fluorescent lipid probes using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP),40 have been the subject of only a handful of publications. Gaub et al.35 reported that UV polymerization of vesicles of dioctadecadienoyl ammonium bromide, a cross-linkable lipid, caused a four-fold reduction in D which was attributed to a low number-average degree of polymerization (Xn). Diacetylene lipids, both pure and mixed with nonpolymerizable, fluid-phase lipids, have been the subject of several studies.41–43 Upon exposure to a high dose of UV irradiation, pure bis-diacetylene lipid bilayers are highly cross-linked which results in D ≈ zero on the timescale of a FRAP measurement.42,43 Lower UV doses, however, produce partially polymerized bilayers in which restricted lateral diffusion of co-incorporated, nonpolymerizable lipids is observed.42,43 Fahmy et al.44 reported that thermal polymerization of bilayers composed of a zwitterionic lipid with a methacryloyl group in one tail caused a 500-fold increase in the time constant for fluorescence bleaching recovery. Kölchens et al.27 examined diffusion in membranes composed of mono- and bis-acryloylphosphatidylcholines that were polymerized using thermal initiation. Their work demonstrated an inverse correlation between D and Xn for linear poly(lipids). When the mole fraction of the bis lipid was greater than 0.3 in mixed mono/bis bilayers, the decrease in D was much greater. In all of these studies, lipid polymerization caused a reduction in D compared to the unpolymerized membranes, and in some cases, a decrease in the mobile fraction was also reported. However degree of reduction varied considerably which is not unexpected based on differences in lipid structure and polymerization method and conditions.

Studies of diffusion behavior in polymerized PSLBs of dienoyl-functionalized phosphatidylcholine lipids have not been published, and are of particular interest in light of reports of greatly enhanced chemical/mechanical stability and retained protein activity in these membranes.30–32,36–39 Here lateral diffusion in unpolymerized and UV polymerized PSLBs formed from dienoyl lipids was characterized using FRAP. The variables examined included the location and number of polymerizable groups in the lipid tails and the effect of polymerization above and below the main phase transition temperature (Tm). In all cases, UV polymerization reduced membrane fluidity; the D values measured after polymerization were 0.1 to 0.8 of those measured before polymerization. This range is comparable to ratios of D values reported for liquid-disordered (Ld) and liquid-ordered (Lo) lipid phases, and suggests that the effect of UV polymerization on lateral diffusion in a dienoyl PSLB is similar to the transition from a Ld phase to a Lo phase. These results provide guidance for creating highly stable poly(lipid) membranes in which the activity of reconstituted transmembrane proteins and peptides is maintained.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (ammonium salt) (rho-PE) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). The structures of bis-sorbyl phosphatidylcholine (bis-SorbPC), mono-sorbyl phosphatidylcholine (mono-SorbPC), bis-dienoyl phosphatidylcholine (bis-DenPC) and mono-dienoyl phosphatidylcholine (mono-DenPC) are shown in Figure S1. bis-SorbPC and mono-SorbPC were prepared via a modified version of that described by Lamparski et al.45,46 Preparatory scale purification of bis-SorbPC was performed by reverse phase HPLC.39 Synthesis of bis-DenPC and mono-DenPC was performed using the methods reported by Jones et al.47 and Liu et al.48 respectively. Lipids were kept at −80 °C for long-term storage and −20 °C for short-term storage. Polymerizable lipids were always handled under yellow light or in darkness during preparation. All water, referred to as DI water, was obtained from a Barnstead Nanopure system (Thermolyne Corporation, Dubuque, IA) with a measured resistivity of greater than 17.5 MΩ-cm.

PSLB formation and UV polymerization

All substrates were 25 × 75 mm microscope slides (Gold Seal, Portsmouth, NH). Slides were cleaned by briefly scrubbing with 1% Liquinox (Alconox, Jersey City, NJ) and a cotton pad, followed by rinsing with DI water and drying under nitrogen. They were then soaked for 5 minutes in 70:30 concentrated sulfuric acid /30% hydrogen peroxide (EMD, Gibbstown, NJ; Caution: this solution is highly corrosive), then rinsed with copious amounts of DI water and blown dry under nitrogen. After cleaning, slides were immediately mounted into a custom sample holder.

Vesicles were prepared from the lipid of interest and ~0.6 mol % rho-PE. A gentle stream of Ar (g) was used to remove chloroform from the lipid solution, followed by drying under vacuum for 4 hours. Lipid mixtures were used within 2 days of drying. If not immediately used, the dried lipid mixture was stored at −20 °C. Immediately before use, the lipid mixture was reconstituted to 0.5 mg/ml in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, then sonicated (at 5–10 °C above the Tm for polymerizable lipids) with an ultrasonicator fitted with a cuphorn (W-380, Heat Systems Ultrasonics, Inc, Farmingdale, NY) until the solution became clear and no visible traces of suspended material remained. Several drops of the solution were then quickly deposited onto the freshly cleaned slide. For polymerizable lipids, the slide was pre-heated to 5–10 °C above the Tm of the respective lipid, and vesicle fusion20,49 was allowed to occur for 30 minutes at 5–10 °C above the Tm of the respective lipid. The sample chamber was then rinsed with at least 20 ml of phosphate buffer at room temperature without exposing the PSLB to air. The PSLB was then reheated to 5–10 °C above the Tm of the respective lipid and examined by epifluorescence microscopy to locate uniform areas on which FRAP was performed. PSLBs composed of DOPC were prepared similarly, except that sonication was performed at 25–35 °C and subsequent manipulations were performed at room temperature.

UV polymerization was carried out at either 5–10 °C above or 5–10 °C below the Tm of the respective polymerizable lipid. The PSLB was illuminated for 30 minutes by a low pressure Hg pen lamp (rated 4500 µW/cm2 at 254 nm) mounted 7.6 cm above the slide. These conditions were sufficient to photoreact nearly 100% of the dienoyl groups in the PSLB (see Supporting Information (SI) for further details) which means that the extent of monomer-polymer conversion was nearly 100%. Minor decreases in rho-PE fluorescence intensity in PSLBs were measured after 30 minutes of UV irradiation.

FRAP

FRAP was performed using a Nikon TE2000-U inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, NJ) with a 20× phase contrast objective. Samples were photobleached in an epi-illumination geometry for < 1 s using the 488 nm line of an Innova 70 Ar ion laser (Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) at a power of ~ 200 mW measured after a neutral density filter placed at the laser exit aperture. Images were captured with a Princeton Instruments CCD camera controlled by an ST-133 controller using WinSpec/32 software (Trenton, NJ). The laser intensity profile was a Gaussian with a radius at 1/e2, ω, between 5 and 17 µm in the first image captured after photobleaching. Regions of interest (ROIs) inside (Iin) and outside (Iout) the bleached spot were monitored before and after bleaching to determine the diffusion coefficients and percent recoveries. To normalize recovery curves, the intensity ratio (F = Iin/Iout) immediately before bleaching was set to unity. A biexponential model (equation 1) composed of two diffusing rho-PE populations, denoted fast and slow, was used to fit recovery curves,

| (1) |

where F(t) is the intensity ratio at a given time, t, after bleaching at t = 0, kx are the rate parameters characteristic of the fast (x = 1) and slow (x = 2) populations, A is the unrecovered fraction, and Bx are the fractions of the fast and slow population. Goodness of fit was evaluated based on the adjusted coefficient of determination and the residuals plot. Residuals from fitting a monoexponential model to recovery curves displayed systematic deviations and lower values for all PSLBs studied, while the residuals from biexponential fits lacked these deviations and values were greater (see SI for a comparison of residuals and values).

Fast and slow diffusion coefficients (D1 and D2, respectively) were computed for each PSLB using40

| (2) |

where γD is a correction factor related to bleach depth (1.1 in all cases) and τx is the half-time for recovery (τx = (ln 2)kx−1). Percent recoveries for the fast and slow components were calculated as

| (3) |

| (4) |

The total percent recovery for the PSLB, %tot, was the sum of %1 and %2. The percent of the bleached fluorescence that did not recover (the percent immobile) is 100 - %tot. A weighted average diffusion coefficient for the mobile fractions, Davg, was also calculated [Davg = %1 (D1) + %2 (D2)] for each PSLB to permit simpler comparisons of the diffusion data.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Unpolymerized PSLBs

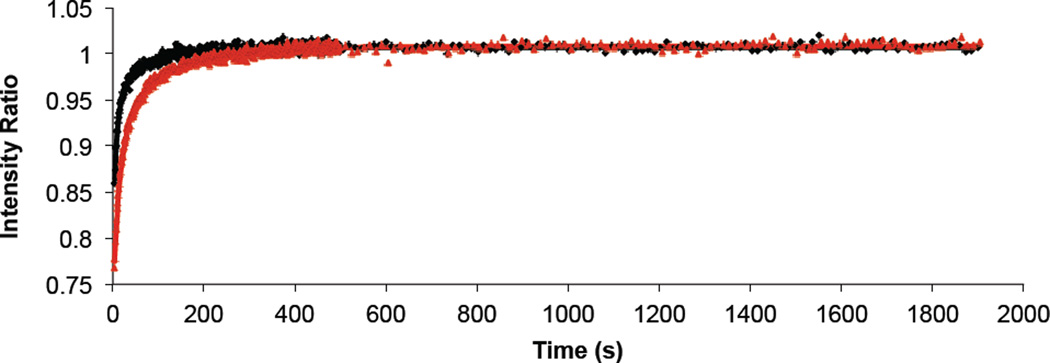

To assess the effects of polymerization on diffusion, FRAP measurements were first performed on PSLBs composed of the unpolymerized dienoyl lipids. Measurements were performed at 5–10 °C above the Tm of the respective lipid which ensured that all PSLBs were in the liquid crystalline-like (Lα) phase. DOPC PSLBs served as a reference sample. Figure 1 shows examples of recovery curves for unpolymerized lipids and fits of equation 1 to these data. Table 1 lists the Tm, the measurement temperature (Tfr), fast and slow diffusion coefficients (D1 and D2, respectively), percent recoveries for the fast and slow components (%1 and %2, respectively), the total percent recovery (%tot), and Davg for all five PSLB types.

Figure 1.

Representative unpolymerized PSLB recovery curves for a mono-DenPC PSLB (black diamonds) and a bis-SorbPC PSLB (red triangles). Solid lines are fits of equation 1 to the data.

Table 1.

Phase transition temperature (Tm), the temperature at which the FRAP measurement was performed (Tfr), diffusion coefficients and percent recoveries for the fast and slow components (D1, %1, D2, %2), total percent recovery (%tot), weighted average diffusion coefficient (Davg), and weighted average diffusion coefficient normalized to 25 °C (D25) of unpolymerized PSLBs.

| Lipid | Tm (°C)* | Tfr (°C) | %1 | %2 | D1 (µm2/s) | D2 (µm2/s) | %tot | Davg (µm2/s) | D25 (µm2/s) | n† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOPC | −17 | 25 | 69 ± 2.3 | 31 ± 2.7 | 6.2 ± 0.80 | 0.62 ± 0.096 | 99 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 5 |

| mono-DenPC | 26 | 35 | 74 ± 7.9 | 26 ± 7.5 | 7 ± 2.3 | 0.5 ± 0.12 | 100 | 5.5 | 4.4 | 6 |

| mono-SorbPC | 32–36 | 43 | 74 ± 2.1 | 26 ± 2.6 | 6 ± 1.5 | 0.31 ± 0.020 | 100 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 5 |

| bis-DenPC | 20 | 30 | 75 ± 2.3 | 28 ± 3.2 | 2.7 ± 0.30 | 0.41 ± 0.062 | 103 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 5 |

| bis-SorbPC | 29 | 37 | 68 ± 2.5 | 31 ± 2.9 | 1.2 ± 0.21 | 0.11 ± 0.020 | 100 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 4 |

Tm data for lipids obtained from published sources48,51–53 and avantilipids.com.

Number of trials.

All unpolymerized PSLBs as well as DOPC PSLBs were found to recover entirely (%tot ≈ 100), with the fast component accounting for 68–75% of the total recovery. Fast and slow diffusing populations with unequal amplitudes were also reported by Scomparin et al.50 for PSLBs of 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) formed on glass via vesicle fusion. A possible source of this behavior is an unequal distribution of rho-PE in the upper and lower leaflets of the bilayer. To probe this distribution, the emission intensity of a DOPC PSLB was measured by epifluorescence microscopy before and after the addition of 500 mM CoCl2 to the aqueous phase above the PSLB. Co2+ quenches the emission of fluorophores in upper leaflet which allows the percentage of fluorophores in each leaflet to be determined by difference.54 After correcting for background intensity and photobleaching, the percent of emission intensity quenched by Co2+ was 68% (±1.2), which agrees well with %1 = 69 (±2.3) for DOPC listed in Table 1. Ajo-Franklin et al.54 reported similar results; they found that 70% of Texas Red DHPE, a fluorescent lipid structurally similar to rho-PE, is in the upper leaflet of egg phosphatidylcholine PSLBs formed by vesicle fusion on glass. The asymmetric distribution may be due to repulsive interactions between the negative charges on the glass surface and the lipid headgroups54 (both rho-PE and Texas Red DHPE have a −1 charge). These results suggest that the biexponential recoveries listed in Table 1 reflect an asymmetric distribution of fast and slow diffusing fluorophores in the upper and lower leaflets, respectively; however, a more extensive study involving other lipids and probes would be required to verify these assignments.

The Davg value for DOPC listed in Table 1 is comparable to results found in the literature.e.g. 55,56 The Davg values of mono-substituted lipids were similar to DOPC, while those of bis-substituted lipids were 2–5 fold lower. However it is difficult to directly compare the diffusion coefficients of these lipids because the FRAP measurements were performed at different temperatures. To perform a temperature-normalized comparison, Davg values were estimated for each lipid at 25 °C, assuming that each lipid is in the Lα phase at this temperature. In a recent paper, diffusion coefficients were measured as a function of temperature for rho-PE in DOPC PSLBs formed by vesicle fusion on glass.56 Using those data, ln(D) vs temperature was plotted over the range of 298–313 K, from which a slope of 0.0215 ln(D)•(K−1) was obtained for DOPC in the Lα phase. The Davg values in Table 1 were then converted to normalized values at 25 °C using

| (5) |

where Tref is 25 °C and D25 is the estimate of Davg at 25 °C in the PSLB composed of the respective dienoyl lipid.

The D25 values of the polymerizable lipids, listed in Table 1, range from 15% to 100% of D25 for DOPC, with the denoyl lipids showing more rapid recovery than the corresponding sorbyl lipids. This difference is likely due to differences in intermolecular forces between the lipids in the center of the bilayer. The sorbyl tail groups can interact via dipole-induced-dipole and dipole-dipole mechanisms, whereas the denoyl tails interact only via dispersion forces in that region of the bilayer. Comparing the sorbyl lipids, diffusion in bis-SorbPC is significantly slower than diffusion in mono-SorbPC, which may be attributable to: a) two sorbyl tail groups are capable of participating in dipole-induced-dipole and dipole-dipole interactions in bis-SorbPC vs only one in mono-SorbPC; and b) the 1-palmitoyl tail in mono-SorbPC is one bond shorter than the corresponding 10-(2’,4’-hexadienoyloxy)decanoyl tail in bis-SorbPC. Comparing the denoyl lipids, the 1-palmitoyl tail in mono-DenPC is two carbons shorter than the corresponding octadeca-2,4-dienoyl tail in bis-DenPC; this difference suggests that diffusion in mono-DenPC should be more rapid which matches the experimental results.

UV polymerization above Tm

Diffusion data for PSLBs polymerized at 5–10 °C above the Tm (i.e., in the Lα phase) are summarized in the upper half of Table 2. To compare changes in the diffusion coefficient resulting from polymerization, FRAP measurements were performed at the same Tfr values and D25 values were computed as described above. Table 2 also includes the Dratio, which is the Davg of a polymerized PSLB divided by the Davg of an unpolymerized PSLB. The range of Dratio values, from 0.19 to 0.79, shows that UV polymerization above the Tm attenuates lateral diffusion to a variable degree; however in all cases, measureable diffusion is retained. In a control experiment, a DOPC PSLB was irradiated for 30 minutes. The Davg values before and after irradiation were 4.2 µm2/s and 4.1 µm2/s, respectively, showing that UV exposure had a minimal effect on lateral diffusion. To further verify that UV polymerization was responsible for the attenuation of diffusion in dienoyl PSLBs, partial polymerization of a bis-SorbPC PSLB was performed by irradiating it for 45 s. The resulting Dratio was 0.42, whereas Dratio for fully polymerized bis-SorbPC was 0.27.

Table 2.

Tfr, D1, %1, D2, %2, %tot, Davg, D25, and Dratio for PSLBs polymerized above and below Tm.

| Lipid | Tfr (°C) | %1 | %2 | D1 (µm2/s) | D2 (µm2/s) | %tot | Davg (µm2/s) | D25 (µm2/s)^ | Dratio* | n† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| polymerization T > Tm | ||||||||||

| mono-DenPC | 35 | 71 ± 2.1 | 28 ± 4.2 | 6 ± 1.0 | 0.65 ± 0.086 | 99 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 0.79 | 4 |

| mono-SorbPC | 43 | 74 ± 4.6 | 25 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 0.22 | 0.37 ± 0.051 | 99 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.54 | 3 |

| bis-DenPC | 30 | 55 ± 2.6 | 38 ± 3.6 | 0.7 ± 0.18 | 0.10 ± 0.034 | 93 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 4 |

| bis-SorbPC | 37 | 52 ± 4.5 | 34 ± 2.5 | 0.4 ± 0.11 | 0.06 ± 0.016 | 86 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 3 |

| polymerization T < Tm | ||||||||||

| mono-DenPC | 35 | 73 ± 11 | 23 ± 8.7 | 6 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 0.29 | 96 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 0.81 | 4 |

| mono-SorbPC | 42 | 70 ± 3.6 | 28 ± 2.0 | 1.6 ± 0.21 | 0.20 ± 0.038 | 98 | 1.2 | 0.84 | 0.28 | 5 |

| bis-DenPC | 30 | 59 ± 4.9 | 36 ± 4.9 | 1.2 ± 0.27 | 0.120 ± 0.0091 | 95 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.34 | 3 |

| bis-SorbPC | 37 | 43 ± 11 | 32 ± 5.4 | 0.2 ± 0.11 | 0.022 ± 0.0090 | 75 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 6 |

Davg value normalized to 25 °C.

Number of trials.

Dratio = (Davg for UV polymerized) (Davg for unpolymerized)−1.

Both mono-DenPC and mono-SorbPC PSLBs maintained 100% recovery after polymerization. There was a minor change in Davg for poly(mono-DenPC), while a moderate decrease was observed for poly(mono-SorbPC), and this occurred entirely in D1. The respective Dratio values of 0.79 and 0.54 suggest that oligomers are formed upon UV polymerization of these lipids. Results reported by several groups provide support for this interpretation.27–29,35 Lamparski and O’Brien28 showed that UV polymerization of mono-SorbPC vesicles produced oligomers with Xn = 3–10, although this result was not correlated with diffusion measurements. Kölchens et al.27 reported both diffusion coefficients and Xn values for mono-acryloyl lipid bilayers polymerized using thermal initiation. Before polymerization, D = 3.8 µm2/s, whereas in polymerized bilayers having Xn values of 233 and 695, D was 1.4 µm2/s and 0.28 µm2/s, respectively. Thus the respective Dratio values were 0.37 and 0.07, significantly less than the Dratio values measured here for poly(mono-SorbPC) and poly(mono-DenPC). Taken together, these findings indicate that the minor to moderate decrease in probe mobility observed here upon polymerization of the mono-substituted dienoyl PSLBs is attributable to a low Xn. (Note: Xn is problematic to determine for a PSLB with an area of a few cm2 because it contains a small number of molecules and their ionization efficiency is very low.39)

The location of the dienoyl groups in these lipids provides a possible explanation for the difference in the Dratio values of poly(mono-DenPC) and poly(mono-SorbPC) bilayers. In the former, polymeric networks are formed adjacent to the glycerol backbone in each leaflet, whereas in the latter, polymerization occurs at the distal ends of the lipid tails (see example structures in SI). Polymerization across the two leaflets also may be possible in sorbyl bilayers, as suggested by Ross et al.19 Inter-leaflet polymerization should present a greater barrier to diffusion than polymerization confined to a single leaflet, in which the number of nearest neighbor molecules should be less compared to inter-leaflet polymerization. This difference is a probable cause for the finding that the Dratio for mono-SorbPC is less than that of mono-DenPC.

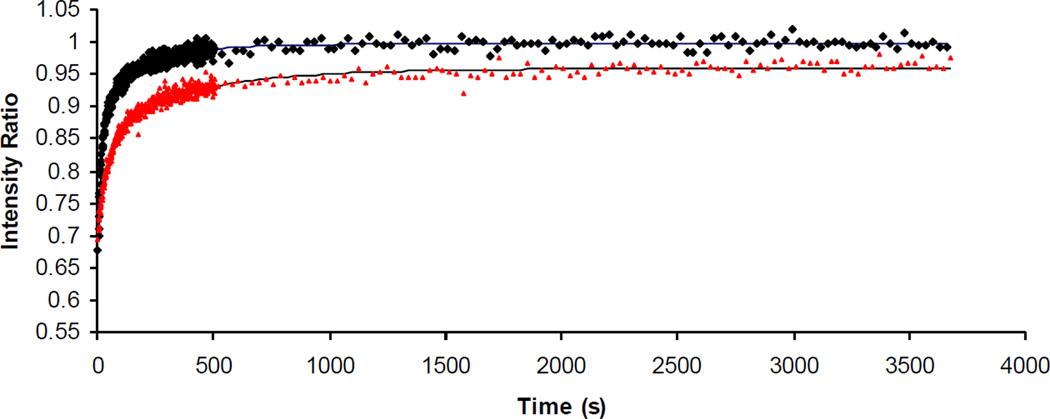

Cross-linking polymerization of PSLBs composed of bis-DenPC and bis-SorbPC above their respective Tm values produced changes in diffusion behavior greater than those observed for the mono-substituted lipids (Table 2). Example recovery curves for bis-SorbPC before and after polymerization are shown in Figure 2. The %tot was less than 100 for both poly(bis-DenPC) (7% immobile) and poly(bis-SorbPC) (14% immobile). Incomplete recovery is likely caused by rho-PE trapped in cross-linked lipid structures that are immobile on the time scale of the FRAP measurement. Relative to the corresponding unpolymerized PSLBs (Table 1), D1, D2 and %1 decreased, while %2 slightly increased.

Figure 2.

Representative recovery curves for an unpolymerized bis-SorbPC PSLB (black diamonds) and a bis-SorbPC PSLB polymerized above the Tm (red triangles). Solid lines are fits of equation 1 to the data.

The D25 values for the mobile fraction in poly(bis-DenPC) and poly(bis-SorbPC) were approximately 11% of the corresponding D25 values for the mono-substituted, polymerized PSLBs. The Dratio values for the cross-linked PSLBs were also significantly less than those observed for the linearly polymerized PSLBs. These trends are consistent with the expectation that cross-linking will generate larger lipo-polymers, resulting in a lower rate of lateral diffusion arising from a more restricted diffusion path.27,29,35 For example, Kölchens et al.27 reported that D in polymerized bilayers composed of an equimolar mixture of mono- and bis-acryloylphosphatidylcholine lipids was more than 10-fold lower than D in polymerized bilayers composed of only the mono-substituted lipid. Gaub et al.35 studied UV polymerized vesicles composed of dioctadecadienoyl ammonium bromide, a lipid with a tail structure similar to that of bis-DenPC. They reported a Dratio of 0.25, quite similar to the values of 0.19 and 0.27 observed here for poly(bis-DenPC) and poly(bis-SorbPC). The authors attributed this “rather small reduction” in diffusion coefficient to a low Xn which was estimated to be <100.35 Likewise, a low Xn is the most probable explanation for the moderate decrease in lateral diffusion that occurs upon polymerization of bis-DenPC and bis-SorbPC.

In summary, the data in the upper half of Table 2 clearly show that after nearly 100% conversion of monomer to polymer (see SI), measurable lateral diffusion is still present in linearly polymerized mono-DenPC and mono-SorbPC and cross-linked bis-DenPC and bis-SorbPC. This result is a marked contrast to bis-diacetylene lipids which, upon exposure to a high dose of UV irradiation that results in near-complete polymerization, form a cross-linked bilayer in which lateral probe diffusion is essentially eliminated on the timescale of a FRAP measurement.43

UV polymerization below Tm

The greater molecular order in the solid-like (Lβ) phase of a lipid bilayer, relative to the Lα phase, may affect lipid polymerization:52 In the Lβ phase, the more ordered lipid tails may be in conformations more favorable for propagating the polymerization reaction. However, slower diffusion in the Lβ phase will reduce the collision frequency, possibly reducing Xn.

Some properties of dienoyl lipids polymerized at temperatures above and below the Tm have been compared in a few studies. Lei et al.52 investigated redox-initiated radical polymerization (redox) of mono-SorbPC vesicles; they found that the rate of polymerization was moderately higher when the reaction was performed above the Tm relative to below the Tm, whereas the difference in Xn was minor (51 in the Lα phase vs 43 in the Lβ phase). In contrast, Lamparski and O’Brien reported that the rate of UV polymerization of sorbyl vesicles is relatively insensitive to the phase of the bilayer, which they ascribed to the low Xn characteristic of this polymerization method.28

Tsuchida et al.33 studied polymerization of mono-DenPC vesicles using redox and visible sensitization methods, and found that both methods generated a larger Xn when the lipids were in the Lα phase. Lipid diffusion was not measured in any of these studies.

Here FRAP of dienoyl lipid PSLBs that were UV polymerized in the Lβ phase was performed to assess if polymerization temperature influences lipid mobility. Polymerization was performed at 5–10 °C below the respective Tm of each lipid and FRAP measurements were made at the same Tfr used in the previous set of experiments. The results, summarized in the lower half of Table 2, show that UV polymerization below the Tm attenuates lateral diffusion to a variable degree; however in all cases, measureable diffusion is retained.

Both mono-DenPC and mono-SorbPC PSLBs maintained 100% recovery after polymerization. The Davg for poly(mono-DenPC) was equivalent to the Davg for this lipid polymerized in the Lα phase. In contrast, the Davg and Dratio values for mono-SorbPC polymerized in the Lβ phase were two-fold less than the corresponding values in the Lα phase. Decreases in both D1 and D2 were observed. This indicates that Lβ phase polymerization of mono-SorbPC produces a more viscous membrane, suggesting a larger Xn.

The locations of the polymerizable groups in mono-DenPC and mono-SorbPC and changes in molecular order in lipid tail region in the Lα and Lβ phases provide a probable explanation for the different results obtained with these lipids. Both theoretical and experimental studies show that in a lamellar lipid bilayer, the lipid tail order parameter, SCD, decreases along the acyl chain from the glycerol backbone to the distal end, showing that the center of the bilayer is more disordered.57 Molecular dynamics simulations as a function of temperature indicate that when a transition from the Lα phase to the Lβ phase occurs, the increase in SCD is greater at the distal ends.58 This suggests that the change in order accompanying the Lα to Lβ phase transition should be greater in the vicinity of the dienoyl group in a mono-SorbPC bilayer relative to a mono-DenPC bilayer. If this increased order promotes polymerization,52 perhaps aided by stronger intermolecular forces between the sorbyl groups, then an increase in Xn and consequent decrease in lateral diffusion may be expected from polymerization of mono-SorbPC in the Lβ phase.

Polymerization of bis-SorbPC PSLBs in the Lβ phase increased the immobile fraction to 25%, indicative of greater rho-PE entrapment in cross-linked domains; this increase was reflected in a corresponding decrease in %1. Relative to polymerization in the Lα phase, D1 and D2 decreased by factors of 2 and 2.7, respectively. These results are consistent with the above discussion regarding the change in SCD at the distal ends of the lipid tails accompanying the Lα to Lβ phase transition. The increase in SCD likely promotes polymerization of sorbyl groups, resulting in a greater Xn and more restricted lateral diffusion. In contrast, when bis-DenPC was polymerized in the Lβ phase, the %tot was equivalent and the Davg was moderately greater in comparison to the results obtained when polymerization was performed in the Lα phase. This result is consistent with the findings of Tsuchida et al.33 discussed above. The difference in the Davg was due primarily to a greater D1 in the Lβ phase. The reasons for this difference are not clear and require further study.

Comparison with diffusion in nonpolymerized lipid phases

The data listed in Tables 1 and 2 show that UV polymerization of PSLBs composed of dienoyl lipids attenuates the lateral mobility of rho-PE to varying degrees. Depending on the lipid and polymerization conditions, up to 25% immobile populations and a 10-fold decrease in Davg was observed; however in all cases, measurable lateral diffusion was retained. As demonstrated in past work, UV polymerization also greatly enhances bilayer stability; for example, the lifetime of a suspended planar membrane composed of bis-DenPC is extended by cross-linking from a few hours to a few weeks.36

It is instructive to compare the Dratio data listed in Table 2 to relative rates of lateral diffusion in the Lα and Lβ phases of a PC lipid bilayer which typically differ by two orders of magnitude. For example, D measured in the Lβ phase of a DMPC PSLB formed by vesicle fusion on glass is about 50-fold less than D measured in the Lα phase.50 The resulting Dratio, 0.02, is less than all Dratio values listed in Table 2, which indicates that UV polymerization of dienoyl PSLBs produces bilayers with lateral mobility intermediate between the Lα and Lβ phases of a model lipid such as DMPC. Only for bis-SorbPC polymerized in the Lβ phase (D25 = 0.08 µm2/s) is diffusion attenuated to a degree comparable to that in the Lβ phase.

A comparison to lipid mixtures that form liquid ordered (Lo) and liquid disordered (Ld) is also instructive. Kayha et al.59 measured diffusion coefficients in giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) composed of DOPC as a function of added cholesterol, which causes a gradual transition from the Ld phase, at high DOPC content, to the Lo phase at high cholesterol content. The D value declined from 6.3 µm2/s for pure DOPC (Lα phase) to 2.4 µm2/s for 2:1 (mol/mol) cholesterol:DOPC (Lo phase), yielding a Dratio of 0.38. The same group also studied ternary GUVs composed of DOPC, 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), and cholesterol, a mixture that is a model for “lipid rafts.”60 GUVs composed of 0.4 DOPC/0.4 DPPC/0.2 cholesterol (mol/mol) form a Ld phase enriched in DOPC and a Lo phase enriched in DPPC/cholesterol. The respective D values were 5.2 µm2/s and 0.44 µm2/s which equate to a Dratio of 0.08. These Dratio values, 0.38 and 0.08, are in the same order of magnitude of the Dratio values listed in Table 2. This comparison suggests that the effect of UV polymerization on lateral diffusion in dienoyl PSLBs can be likened to a transition from a Ld phase to a Lo phase, and is attributed to the low Xn characteristic of this polymerization method. It is important to emphasize, however, that this comparison of rho-PE diffusivity does not imply that there is any structural similarity between a poly(dienoyl) lipid bilayer and a Lo–phase lipid bilayer; for example, lipid packing and order in these two types of bilayers are certainly dissimilar.

These findings provide additional perspective to published studies reporting that in some cases, proteins incorporated into UV polymerized dienoyl lipid bilayers retain activity: a) bRho, the canonical G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), retains photoactivity in poly(mono-SorbPC) and poly(bis-SorbPC),37,38 which shows that the lower fluidity in these membranes does not inhibit the conformational change that accompanies bRho activation. This suggests that membrane properties that are thought to modulate GPCR activation, such as intrinsic lipid curvature and elastic moduli,14–16 are not significantly altered upon polymerization of sorbyl lipid bilayers. In contrast, bis-DenPC polymerization eliminates bRho activity; the formation of cross-linked networks near the glycerol backbone may stiffen the bilayer such that it cannot accommodate the conformational change associated with bRho activation.38 b) When protein or peptide subunits must reversibly associate in a membrane to form a functional transmembrane ion channel (IC), the lower fluidity of a poly(lipid) may attenuate or eliminate IC activity. For example, alamethicin oligomerizes to form ICs in a unpolymerized bis-DenPC bilayer but the IC activity is nearly eliminated after UV polymerization.31 The lower fluidity of poly(bis-DenPC) appears to exceed a threshold for reversible peptide oligomerization. However mixtures of poly(bis-DenPC) and a nonpolymerizable lipid such as diphytanoyl phosphatidylcholine are sufficiently fluid to support alamethicin activity.31

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

UV polymerization of dienoyl lipid PSLBs was performed in both the Lα and Lβ phases and, in all cases, caused a reduction in membrane fluidity. However measurable lateral diffusion was present in all four types of poly(lipid) bilayers, which is attributable to a low Xn that appears to be characteristic of UV-initiated polymerization of these lipids. D25 values were lower for the poly(sorbyl) lipids vs the poly(denoyl) lipids which may be due to inter-leaflet polymerization. Polymerization in the Lβ phase caused a marked reduction in D25, relative to polymerization in the Lα phase, for sorbyl lipid bilayers. This result is attributed to the increase in SCD at the distal ends of the lipid tails in the Lβ phase which is hypothesized to produce dienoyl group conformations more favorable for polymerization, resulting in a greater Xn.

The Dratio range of 0.11 to 0.81 indicates that UV polymerization of dienoyl PSLBs produces bilayers with lateral mobility intermediate between the Lα and Lβ phases of a conventional lipid such as DMPC. This range of Dratio values is comparable to ratios of D values reported for Lo vs Ld lipid phases. This comparison suggests that the effect of UV polymerization on lateral diffusion in a dienoyl PSLB is similar to a transition from a Ld phase to a Lo phase. It also suggests why some transmembrane proteins retain function in poly(dienoyl lipid) membranes. The activity of a protein reconstituted in a UV polymerized dienoyl lipid bilayer will depend on a number of factors, some of which are specific to the protein. Thus a generalization in terms of protein characteristics cannot be stated; however, the comparison to the Lo phase may be appropriate with respect to membrane mechanical properties and their effect on protein function. In other words, if a protein is active when reconstituted in a Lo phase, then we hypothesize that it might be active in a UV polymerized dienoyl lipid bilayer. Future studies will be designed to address this hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. C. Scomparin for helpful discussions and Katherine R. Leight for preparing the figure in SI showing the structures of linearly polymerized lipids. Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01EB007047. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Chemical structures of polymerizable lipids, determination of UV polymerization time for PSLBs, structures of linearly polymerized lipids, and a comparison of fitting mono- and biexponential models to a recovery curve. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Castellana ET, Cremer PS. Solid Supported Lipid Bilayers: From Biophysical Studies to Sensor Design. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2006;61:429–444. doi: 10.1016/j.surfrep.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan YHM, Boxer SG. Model Membrane Systems and Their Applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:581–587. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller A, O'Brien DF. Supramolecular Materials via Polymerization of Mesophases of Hydrated Amphiphiles. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:727–758. doi: 10.1021/cr000071g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puri A, Blumenthal R. Polymeric Lipid Assemblies as Novel Theranostic Tools. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:1071–1079. doi: 10.1021/ar2001843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H, Joubert JR, Saavedra SS. Membranes from Polymerizable Lipids. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2010;224:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reimhult E, Baumann MK, Kaufmann S, Kumar K, Spycher PR. Advances in Nanopatterned and Nanostructured Supported Lipid Membranes and Their Applications. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. 2010;27:185–216. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2010.10648150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka M, Sackmann E. Polymer-Supported Membranes as Models of the Cell Surface. Nature. 2005;437:656–663. doi: 10.1038/nature04164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janshoff A, Steinem C. Transport Across Artificial Membranes - An Analytical Perspective. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006;385:433–451. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reimhult E, Kumar K. Membrane Biosensor Platforms Using Nano- And Microporous Supports. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiefenauer L, Demarche S. Challenges in the Development of Functional Assays of Membrane Proteins. Materials. 2012;5:2205–2242. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackman JA, Knoll W, Cho N-J. Biotechnology Applications of Tethered Lipid Bilayer Membranes. Materials. 2012;5:2637–2657. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz AJ, Albertorio F, Daniel S, Cremer PS. Double Cushions Preserve Transmembrane Protein Mobility in Supported Bilayer Systems. Langmuir. 2008;24:6820–6826. doi: 10.1021/la800018d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giess F, Friedrich MG, Heberle J, Naumann RL, Knoll W. The Protein-Tethered Lipid Bilayer: A Novel Mimic of the Biological Membrane. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3213–3220. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen OS, Koeppe RE. Bilayer Thickness and Membrane Protein Function: An Energetic Perspective. Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2007;36:107–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown MF. Curvature Forces in Membrane Lipid-Protein Interactions. Biochemistry. 2012;51:9782–9795. doi: 10.1021/bi301332v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips R, Ursell T, Wiggins P, Sens P. Emerging Roles for Lipids in Shaping Membrane-Protein Function. Nature. 2009;459:379–385. doi: 10.1038/nature08147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng WWL, D'Avanzo N, Doyle DA, Nichols CG. Dual-Mode Phospholipid Regulation of Human Inward Rectifying Potassium Channels. Biophys. J. 2011;100:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniel S, Albertorio F, Cremer PS. Making Lipid Membranes Rough, Tough, and Ready to Hit the Road. MRS Bull. 2006;31:536–540. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross EE, Rozanski LJ, Spratt T, Liu S, O'Brien DF, Saavedra SS. Planar Supported Lipid Bilayer Polymers Formed by Vesicle Fusion. 1. Influence of Diene Monomer Structure and Polymerization Method on Film Properties. Langmuir. 2003;19:1752–1765. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cremer PS, Boxer SG. Formation and Spreading of Lipid Bilayers on Planar Glass Supports. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:2554–2559. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McBee TW, Saavedra SS. Stability of Lipid Films Formed on gamma-Aminopropyl Monolayers. Langmuir. 2005;21:3396–3399. doi: 10.1021/la047646f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albertorio F, Diaz AJ, Yang T, Chapa VA, Kataoka S, Castellana ET, Cremer PS. Fluid and Air-Stable Lipopolymer Membranes for Biosensor Applications. Langmuir. 2005;21:7476–7482. doi: 10.1021/la050871s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malmstadt N, Jeon LJ, Schmidt JJ. Long-Lived Planar Lipid Bilayer Membranes Anchored to an in Situ Polymerized Hydrogel. Adv. Mater. 2008;20:84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ringsdorf H, Schlarb B, Venzmer J. Molecular Architecture and Function of Polymeric Oriented Systems - Models for the Study of Organization, Surface Recognition, and Dynamics of Biomembranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1988;27:113–158. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cashion MP, Long TE. Biomimetic Design and Performance of Polymerizable Lipids. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:1016–1025. doi: 10.1021/ar800191s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien DF, Armitage B, Benedicto A, Bennett DE, Lamparski HG, Lee YS, Srisiri W, Sisson TM. Polymerization of Preformed Self-Organized Assemblies. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:861–868. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolchens S, Lamparski H, O'Brien DF. Gelation of Two-Dimensional Assemblies. Macromolecules. 1993;26:398–400. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamparski H, O'Brien DF. Two-Dimensional Polymerization of Lipid Bilayers:Degree of Polymerization of Sorbyl Lipids. Macromolecules. 1995;28:1786–1794. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sisson TM, Lamparski HG, Kolchens S, Elayadi A, O'Brien DF. Cross-Linking Polymerizations in Two-Dimensional Assemblies. Macromolecules. 1996;29:8321–8329. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conboy JC, Liu S, O'Brien DF, Saavedra SS. Planar Supported Bilayer Polymers Formed from Bis-Diene Lipids by Langmuir-Blodgett Deposition and UV Irradiation. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:841–849. doi: 10.1021/bm0256193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heitz BA, Jones IW, Hall HK, Aspinwall CA, Saavedra SS. Fractional Polymerization of a Suspended Planar Bilayer Creates a Fluid, Highly Stable Membrane for Ion Channel Recordings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:7086–7093. doi: 10.1021/ja100245d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heitz BA, Xu J, Jones IW, Keogh JP, Comi TJ, Hall HK, Aspinwall CA, Saavedra SS. Polymerized Planar Suspended Lipid Bilayers for Single Ion Channel Recordings: Comparison of Several Dienoyl Lipids. Langmuir. 2011;27:1882–1890. doi: 10.1021/la1025944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuchida E, Hatashita M, Makino C, Hasegawa E, Kimura N. Polymerization of Unsaturated Phospholipids as Large Unilamellar Liposomes at Low Temperature. Macromolecules. 1992;25:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaub H, Büschl R, Ringsdorf H, Sackmann E. Phase Transitions, Lateral Phase Separation and Microstructure of Model Membranes Composed of a Polymerizable Two-Chain Lipid and Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1985;37:19–43. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaub H, Sackmann E, Büschl R, Ringsdorf H. Lateral Diffusion and Phase Separation in Two-Dimensional Solutions of Polymerized Butadiene Lipid in Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine Bilayers. A Photobleaching and Freeze Fracture Study. Biophys. J. 1984;45:725–731. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84215-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heitz BA, Xu J, Hall HK, Aspinwall CA, Saavedra SS. Enhanced Long-Term Stability for Single Ion Channel Recordings Using Suspended Poly(lipid) Bilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6662–6663. doi: 10.1021/ja901442t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Subramaniam V, Alves ID, Salgado GFJ, Lau P-W, Wysocki RJ, Salamon Z, Tollin G, Hruby VJ, Brown MF, Saavedra SS. Rhodopsin Reconstituted into a Planar-Supported Lipid Bilayer Retains Photoactivity after Cross-Linking Polymerization of Lipid Monomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5320–5321. doi: 10.1021/ja0423973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subramaniam V, Ambruoso GD, Hall HK, Wysocki RJ, Brown MF, Saavedra SS. Reconstitution of Rhodopsin into Polymerizable Planar Supported Lipid Bilayers: Influence of Dienoyl Monomer Structure on Photoactivation. Langmuir. 2008;24:11067–11075. doi: 10.1021/la801835g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang B, Ju Y, Joubert JR, Kaleta EJ, Lopez R, Jones IW, Hall HK, Jr, Ratnayaka SN, Wysocki VH, Saavedra SS. Label-Free Detection and Identification of Protein Ligands Captured by Receptors in a Polymerized Planar Lipid Bilayer Using MALDI-TOF MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015;407:2777–2789. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-8508-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Axelrod D, Koppel DE, Schlessinger J, Elson E, Webb WW. Mobility Measurement by Analysis of Fluorescence Photobleaching Recovery Kinetics. Biophys. J. 1976;16:1055–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sackmann E, Eggl P, Fahn C, Bader H, Ringsdorf H, Schollmeier M. Compound Membranes of Linearly Polymerized and Cross-Linked Macrolipids with Phospholipids: Preparation, Microstructure and Applications. Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 1985;89:1198–1208. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okazaki T, Inaba T, Tatsu Y, Tero R, Urisu T, Morigaki K. Polymerized Lipid Bilayers on a Solid Substrate: Morphologies and Obstruction of Lateral Diffusion. Langmuir. 2009;25:345–351. doi: 10.1021/la802670t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morigaki K, Kiyosue K, Taguchi T. Micropatterned Composite Membranes of Polymerized and Fluid Lipid Bilayers. Langmuir. 2004;20:7729–7735. doi: 10.1021/la049340e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fahmy T, Wesser J, Spiess HW. Structure and Molecular Dynamics of Highly Mobile Polymer Membranes. Angew. Makromol. Chem. 1989;166:39–56. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lamparski H, Liman U, Barry JA, Frankel DA, Ramaswami V, Brown MF, O'Brien DF. Photoinduced Destabilization of Liposomes. Biochemistry. 1992;31:685–694. doi: 10.1021/bi00118a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lamparski H. Polymerization in Two-Dimensional Assemblies of Sorbyl Containing Lipids. PhD Dissertation. University of Arizona; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones IW, Hall HK., Jr Demonstration of a Convergent Approach to UV-Polymerizable Lipids bisDenPC and bisSorbPC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:3699–3701. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu S, Sisson TM, O'Brien DF. Synthesis and Polymerization of Heterobifunctional Amphiphiles to Cross-Link Supramolecular Assemblies. Macromolecules. 2001;34:465–473. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reimhult E, Hook F, Kasemo B. Intact Vesicle Adsorption and Supported Biomembrane Formation From Vesicles in Solution: Influence of Surface Chemistry, Vesicle Size, Temperature, and Osmotic Pressure. Langmuir. 2003;19:1681–1691. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scomparin C, Lecuyer S, Ferreira M, Charitat T, Tinland B. Diffusion in Supported Lipid Bilayers: Influence of Substrate and Preparation Technique on the Internal Dynamics. Eur. Phys. J. E. 2009;28:211–220. doi: 10.1140/epje/i2008-10407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lamparski H, Lee YS, Sells TD, O'Brien DF. Thermotropic Properties of Model Membranes Composed of Polymerizable Lipids. 1. Phosphatidylcholines Containing Terminal Acryloyl, Methacryloyl, and Sorbyl Groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:8096–8102. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lei J, Sisson TM, Lamparski HG, O'Brien DF. Two-Dimensional Polymerization of Lipid Bilayers: Effect of Lipid Lateral Diffusion on the Rate and Degree of Polymerization. Macromolecules. 1999;32:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu S, O'Brien DF. Cross-Linking Polymerization in Two-Dimensional Assemblies: Effect of the Reactive Group Site. Macromolecules. 1999;32:5519–5524. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ajo-Franklin CM, Yoshina-Ishii C, Boxer SG. Probing the structure of supported membranes and tethered oligonucleotides by fluorescence interference contrast microscopy. Langmuir. 2005;21:4976–4983. doi: 10.1021/la0468388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seu KJ, Pandey AP, Haque F, Proctor EA, Ribbe AE, Hovis JS. Effect of Surface Treatment on Diffusion and Domain Formation in Supported Lipid Bilayers. Biophys. J. 2007;92:2445–2450. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.099721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bag N, Yap DHX, Wohland T. Temperature Dependence of Diffusion in Model and Live Cell Membranes Characterized by Imaging Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. BBA-Biomembranes. 2014;1838:802–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vermeer LS, de Groot BL, Reat V, Milon A, Czaplicki J. Acyl Chain Order Parameter Profiles in Phospholipid Bilayers: Computation from Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Comparison with H-2 NMR Experiments. Eur. Biophys. J. 2007;36:919–931. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sum AK, Faller R, Pablo JJd. Molecular Simulation Study of Phospholipid Bilayers and Insights of the Interactions with Disaccharides. Biophys. J. 2003;85:2830–2844. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74706-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kahya N, Scherfeld D, Bacia K, Schwille P. Lipid Domain Formation and Dynamics in Giant Unilamellar Vesicles Explored by Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 2004;147:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scherfeld D, Kahya N, Schwille P. Lipid Dynamics and Domain Formation in Model Membranes Composed of Ternary Mixtures of Unsaturated and Saturated Phosphatidylcholines and Cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2003;85:3758–3768. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74791-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.