Abstract

Objectives

The authors sought to determine the prevalence of unknown HIV status among emergency department (ED) patients, how it has changed over time, and whether it differs according to patient characteristics.

Methods

The authors used electronic medical record data to identify whether HIV status was known or unknown among patients aged ≥13 seen in the ED of a large, urban medical center between 2006 and 2011. The authors used multivariate logistic regression to identify the characteristics associated with unknown HIV status.

Results

The prevalence of unknown HIV status decreased each year, from 87.7% in 2006 to 74.9% in 2011 (P < .001). Characteristics associated with unknown HIV status included being nonblack, in the youngest and oldest age-groups, and nonpublically insured. Compared to men, women without prior pregnancy were equally likely to have unknown HIV status, but women with prior pregnancy were significantly less likely to have unknown HIV status.

Conclusion

The prevalence of unknown HIV status is decreasing, but in 2011 75% of ED patients aged ≥13 still had unknown status, and it was associated with specific patient characteristics. Understanding the trends in the prevalence of unknown HIV status and how it is associated with patient characteristics should inform the design and implementation of expanded HIV-testing strategies.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, unknown HIV status, expanded HIV testing, emergency department

Introduction

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that 18.1% of the 1.2 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States have undiagnosed infection.1 Individuals with undiagnosed HIV are at increased risk of adverse clinical outcomes due to delayed access to antiretro-viral therapy (ART).2,3 They are also thought to contribute disproportionately to transmission of HIV due to continued risk behaviors.4,5 A targeted, risk-based approach to testing has been associated with missed opportunities for HIV diagnosis and high rates of undiagnosed infection.6,7 To address this problem, in 2006, the CDC released recommendations for expanded HIV testing that includes nontargeted testing for persons aged 13 to 64 during routine medical encounters, including during visits to the emergency department (ED).8

Nontargeted, expanded HIV-testing strategies seek to decrease the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV by increasing testing among individuals with unknown HIV status—those who are not known to be either HIV positive or HIV negative. Although numerous studies have described outcomes associated with expanded HIV-testing strategies,9-16 most do not report on the prevalence of unknown HIV status or the impact that expanded strategies have on this key metric. Studies that have reported on the proportion of patients with unknown HIV status have primarily relied on a self-reported history of prior HIV testing,17-20 a method that may not accurately reflect the scope of the problem.21-23 Therefore, among the published studies, little is known about the prevalence of unknown HIV status or how it is affected by different testing strategies.

To inform the development and evaluation of an expanded HIV-testing strategy in the ED of a large urban health care system, we applied an algorithm using information available in the electronic medical record (EMR) to identify patients with unknown HIV status. Using this algorithm, we first described the prevalence of unknown HIV status among ED patients. We then determined whether there has been a secular trend in this prevalence prior to the implementation of a formal expanded HIV-testing strategy. Finally, we assessed whether the prevalence of unknown HIV status differed by patient's demographic characteristics.

Methods

Population and Setting

We conducted our study in Bronx in New York City, one of the epicenters of the HIV epidemic in the United States. The Bronx has a total population of 1.4 million and the prevalence of HIV in 2010 was 1.7%.24 Montefiore Medical Center (MMC) is the single largest health care provider in Bronx and includes 3 adult hospitals, a pediatric hospital, EDs affiliated with each of the hospitals, and greater than 50 outpatient clinics in the Bronx. All sites share an EMR that was first introduced in 1997 and includes patient problem lists, visit history with billing information, and laboratory test results. By the end of 2011, data from approximately 1.5 million unique patients were captured in the EMR.

We focused our study on the population of MMC's largest ED (adult and pediatric) because this will be the first of MMC's hospital-based sites to formally implement an expanded HIV-testing strategy. Although the CDC recommendation for nontargeted HIV testing specifies those between the age of 13 and 64, we also included those older than 64 in our study because, in our population, older patients remain at substantial risk for late diagnosis of HIV.25 We focused on the time period between 2006 and 2011 because this period coincides with numerous interventions at the city, state, and federal levels aimed at increasing the rates of HIV testing.8,26-28 Apart from prenatal HIV testing which has been routinely offered in accordance with New York State law since 1996, no institution-wide strategy addressing HIV testing was implemented during the study period.

Ascertainment of HIV Status

Our primary outcome of interest was unknown HIV status. Patients with unknown HIV status were defined as those who were not known to be either HIV positive or HIV negative. We used a previously described algorithm utilizing laboratory, billing, and problem-list data available in the EMR to ascertain whether a patient was known to be HIV positive, HIV negative, or have unknown HIV status at the time of presentation to the ED.29 The algorithm identifies a patient as HIV positive if the patient has a positive HIV Western blot, a detectable HIV viral load, an HIV-related entry on the problem list, a single inpatient admission, 2 outpatient visits associated with an HIV-related International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code, or 2 undetectable HIV viral loads sent concurrently with a CD4 count (to identify HIV-positive patients suppressed on ART). The algorithm identifies a patient as HIV negative if the patient does not fulfill criteria as being HIV positive, and there is a negative HIV antibody test in the EMR, regardless of how long ago the test was performed. Although identifying a patient as HIV negative based on a prior negative result ignores the potential impact of subsequent HIV risk behaviors, we chose this definition based on New York State's Public Health Law mandating that patients aged 13 to 64 in health care settings be offered HIV testing at least once.28 The algorithm is applied using health surveillance software (Clinical Looking Glass, Yonkers, New York) and only processes data in the EMR of the affiliated health care system (ie, results of HIV tests performed outside the MMC system are not accessible).

Prevalence of Unknown HIV Status and Change over Time

To examine the prevalence of unknown HIV status and ascertain how this prevalence changed over time, we performed serial applications of the algorithm to all unique patients aged 13 and older who were seen in the ED from 2006 to 2011. HIV status of patients with multiple visits in a calendar year was ascertained at the time of their first visit of the year. HIV status of patients with visits in different calendar years was ascertained in each of those years.

We calculated the prevalence of unknown status using the annual number of unique ED patients as the denominator and those identified as having unknown HIV status in the numerator. We then assessed the change in the prevalence of unknown HIV status over time using a logistic regression model, with year of ED visit as the independent variable and unknown HIV status as the dependent variable.

Association between Demographic Characteristics and Unknown HIV Status

In order to examine the association between patients' demographic characteristics and unknown HIV status among patients who had a prior opportunity to be tested for HIV in the affiliated health care system, we restricted our analysis to those ED patients in 2011 who had at least 1 visit (inpatient admission, outpatient visit, or ED visit) to the affiliated health care system prior to the 2011 ED visit. All demographic data were collected from the EMR and included gender (male/ female); age; race/ethnicity (black, white, Hispanic, or other); preferred language (English, Spanish, or other); insurance status (public [Medicare or Medicaid], private, or uninsured); and, for women, a history of prior pregnancy. Prior pregnancy was defined as ever having a positive pregnancy test or a perinatal-related ICD-9-CM billing code in the EMR.

We assessed for associations between demographic characteristics and unknown HIV status using chi-square tests. Demographic characteristics found to be significantly associated with unknown HIV status on bivariate testing at a P value ≤ .10 were included as covariates in a multivariate logistic regression model with unknown HIV status as the dependent variable. All analyses were performed using STATA version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Results

Prevalence of Unknown HIV Status and Change over Time

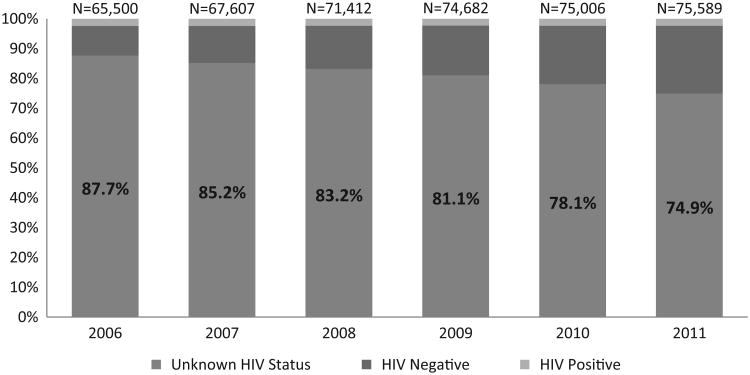

Among the number of unique ED patients which ranged from 65 500 in 2006 to 75 589 in 2011, the prevalence of unknown HIV status decreased each year from 87.7% in 2006 to 74.9% in 2011 (P < .001; Figure 1). The decrease in the prevalence of patients with unknown HIV status between 2006 and 2011 is accounted for by an increasing prevalence of patients with a prior negative HIV test rather than a change in the prevalence of HIV-positive patients.

Figure 1.

HIV status among all unique emergency department (ED) patients aged ≥13 in 2006 to 2011*.

*For patients with multiple ED visits in a single calendar year, HIV status was determined at the time of their earliest visit of the year. Patients with multiple visits were counted once in each calendar year but were counted in multiple years.

Association between Demographic Characteristics and Unknown HIV Status

Of the 75 589 unique ED patients in 2011, 14 152 (18.7%) had no prior visit to the affiliated health care system. Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the 61 437 patients who had at least 1 visit prior to their 2011 ED visit. The patients were predominantly female (63.3%), with substantial representation across all age-groups. Among women, 18% had a prior pregnancy. The majority of patients were Hispanic (52.1%), one-third were black (33.6%), and 15.9% identified Spanish as their preferred language. Most patients had public insurance (60.6%) and 10.6% were uninsured.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Unique Emergency Department Patients in 2011 with at least 1 Prior Visit to the Affiliated Health Care System.a

| Characteristic | ED population 2011, N = 61 437, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 38 898 (63.3) |

| Prior pregnancyb | |

| No | 31 844 (81.9) |

| Yes | 7 047 (18.1) |

| Missing | 7 (0.01) |

| Age, years | |

| 13-17 | 4 987 (8.1) |

| 18-24 | 8 192 (13.3) |

| 25-34 | 9 435 (15.4) |

| 35-44 | 8 516 (13.9) |

| 45-54 | 10 261 (16.7) |

| 55-64 | 8130 (13.2) |

| ≥65 | 11 916 (19.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black | 20 664 (33.6) |

| White | 4695 (7.6) |

| Hispanic | 32 019 (52.1) |

| Other | 2752 (4.5) |

| Missing | 1307 (2.1) |

| Preferred language | |

| English | 50 638 (82.4) |

| Spanish | 9773 (15.9) |

| Other | 710 (1.2) |

| Missing | 316 (0.5) |

| Insurance | |

| Publicc | 37 201 (60.6) |

| Private | 17 029 (27.7) |

| Uninsured | 6516 (10.6) |

| Missing | 691 (1.1) |

Abbreviation: ED, emergency department.

A prior visit included any inpatient admission, outpatient visit, or ED visit in the affiliated health care system between 1997 (inception of electronic medical record) and first ED visit of 2011.

Females only.

Medicare or Medicaid.

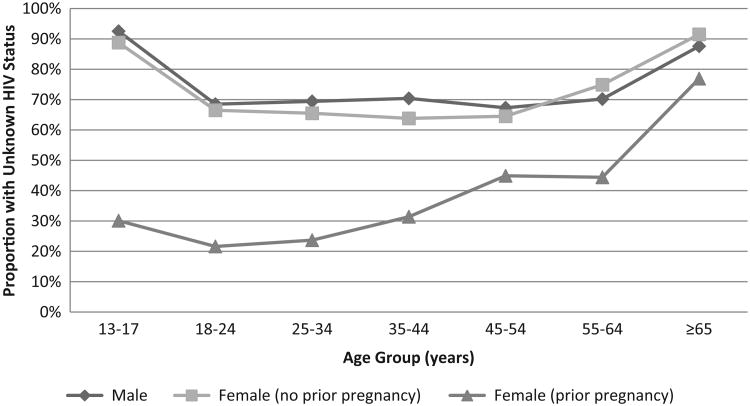

Overall, 42 586 (69.3%) patients had unknown HIV status. Figure 2 displays the association between age and unknown HIV status stratified by gender and pregnancy status. Among men and among women with no prior pregnancy, the prevalence of unknown HIV status is represented by a u-shaped curve, with the highest rates of unknown status among the youngest and oldest age categories and the lowest rates among the middle-age categories. For all age-groups, women with a prior pregnancy had the lowest rates of unknown HIV status. Table 2 demonstrates unadjusted and adjusted results for the association between demographic characteristics and unknown HIV status. In the adjusted model, women with prior pregnancy had the lowest likelihood of having unknown HIV status (odds ratio [OR] 0.17 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.16-0.19). After adjustment, significant differences also remained according to age with the middle age-groups having a lower likelihood of having unknown HIV status compared to the younger and older age-groups. In addition, black patients (versus those of other race/ethnicities) and publicly insured patients (versus those who were commercially insured or uninsured) had a significantly lower likelihood of having unknown HIV status.

Figure 2.

Proportion of emergency department patients in 2011 with unknown HIV status by age, gender, and prior pregnancy.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for Associations between Demographic Characteristics and Unknown HIV Status.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | Ref | Ref |

| Female (prior pregnancy) | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 0.97 (0.93-1.01) |

| Female (no prior pregnancy) | 0.12 (0.11-0.13)b | 0.17 (0.16-0.19)b |

| Age | ||

| 13-17 | 6.07 (5.52-6.66)b | 4.33 (3.92-4.78)b |

| 18-24 | 1.14 (1.08-1.21)b | 1.01 (0.94-1.07) |

| 25-34 | Ref | Ref |

| 35-44 | 1.25 (1.17-1.32)b | 1.08 (1.01-1.15) |

| 45-54 | 1.55 (1.47-1.64)b | 1.06 (0.99-1.13) |

| 55-64 | 2.29 (2.15-2.44)b | 1.46 (1.36-1.57)b |

| ≥65 | 7.71 (7.17-8.28)b | 5.20 (4.80-5.64)b |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | Ref | Ref |

| White | 2.88 (2.64-3.14)b | 1.96 (1.79-2.15)b |

| Hispanic | 1.02 (0.98-1.05) | 1.08 (1.04-1.13)b |

| Other | 1.57 (1.44-1.73)b | 1.59 (1.44-1.76)b |

| Preferred language | ||

| English | Ref | Ref |

| Spanish | 1.18 (1.13-1.24)b | 1.01 (0.95-1.07) |

| Other | 1.66 (1.39-1.99)b | 1.16 (0.94-1.42) |

| Insurance | ||

| Public | Ref | Ref |

| Private | 1.08 (1.04-1.12)b | 1.43 (1.37-1.50)b |

| Uninsured | 1.07 (1.01-1.14) | 1.67 (1.56-1.78)b |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; Ref, reference.

Model adjusted for gender, prior pregnancy, age, race/ethnicity, preferred language, and insurance status.

P < .001.

Discussion

Despite a significant decrease in the prevalence of unknown HIV status among ED patients of a large urban health care system, in 2011, approximately three-quarters of patients still had unknown HIV status. Therefore, the majority of patients remain at risk of undiagnosed HIV infection. Furthermore, specific patient demographic characteristics are associated with having unknown HIV status. These observations are critical for the effective design, implementation, and evaluation of strategies that further expand HIV testing.

Our study demonstrates a novel approach to ascertaining the prevalence of unknown HIV status, a key metric for expanded HIV-testing strategies. While numerous strategies for expanded HIV testing have been described in the literature, outcomes reported include the number of HIV tests performed,26 proportion of ED visits during which HIV testing is performed,15 number of new HIV diagnoses made,11 stage of disease at the time of diagnosis,13 and process measures such as patient acceptability of the routine offer for testing.14 Among studies that have described the prevalence of unknown HIV status17,18 or the impact of an expanded strategy on the prevalence of unknown HIV status,20 the method of ascertaining unknown HIV status has primarily been a self-reported history of HIV testing. In contrast to these studies, we demonstrate the use of an EMR-based algorithm to ascertain an objective estimate of the prevalence of unknown HIV status and describe how this prevalence has changed over time. Serial applications of the algorithm after implementation of an expanded HIV-testing strategy in the ED will enable evaluation of the strategy's impact on the key outcome of testing a previously untested population. Furthermore, we have demonstrated how this approach provides insight into HIV-testing disparities among populations that must be considered in the implementation of expanded HIV-testing strategies.

The decreasing trend in unknown HIV status among ED patients between 2006 and 2011 coincides with multiple large-scale HIV-testing interventions that are likely to have impacted our observations.8,26-28 Because our study took place in a region of high HIV prevalence where city, state, and federal resources have been invested in increasing rates of HIV testing, our study population was likely exposed to a higher concentration of these interventions compared to regions with lower HIV prevalence. With the release of the revised CDC recommendations for expanded HIV testing in 2006, however, interventions to increase the rates of HIV testing have proliferated across the country,10 and guidelines from numerous other organizations have also endorsed expanded testing strategies.30,31 Therefore, we expect that similar decreasing trends in the prevalence of unknown HIV status may be seen in other regions as well. Identifying this secular trend is critical for the evaluation of any new HIV-testing intervention because it must be accounted for when assessing a change in the prevalence of unknown HIV status after implementation of the new intervention.

While disparities in rates of HIV testing have been recognized across demographic groups in the general population,32,33 little is known about these disparities in the ED population.17,18 We identified several important associations between unknown HIV status and patients' demographic characteristics. We found that women with a prior pregnancy had the lowest likelihood of having unknown HIV status across all age-groups, and prior pregnancy remained the strongest predictor of unknown status in multivariate analysis. These results support the ability of routine prenatal HIV testing (formalized in New York State in 1999) to effectively decrease the proportion of women with unknown HIV status and suggests that large-scale, expanded HIV-testing strategies can significantly decrease the proportion of patients with unknown HIV status across a broad range of demographic groups.

We also found significant associations between age, race, and insurance status with unknown HIV status. Patients who were black, in the middle-age groups, and who received publicly funded insurance were least likely to have unknown HIV status. These results appear to reflect a legacy of targeted testing of patients thought to be at higher risk for HIV and the impact of expanded testing efforts to date and are consistent with a prior study.18 Recognizing these disparities in the prevalence of unknown HIV status is vital to the understanding the impact of expanded testing strategies. A successful non-targeted HIV-testing strategy, one that truly expands testing to populations with historically lower rates of testing, should attenuate these associations between demographic characteristics and unknown HIV status.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. First, our definitions of known and unknown HIV status rely on information available in the EMR of a single health care system. Because HIV tests performed outside this system are not accounted for, our measurement may represent an overestimation of the prevalence of unknown HIV status in the ED population. Despite being a single system, however, the extent of the system's network has allowed for encounters with a substantial proportion of the local population. Furthermore, an estimate of the proportion of patients seen in the affiliated medical system's ED who may have been tested for HIV outside this system can be gleaned from our measurement of unknown HIV status among women with a history of pregnancy. While we identified that 21.6% and 23.7% of women aged 18 to 24 and 25 to 34 with a prior pregnancy, respectively, had unknown HIV status, the New York State Department of Health reports that by 2010, only 4% to 5% of pregnant women in New York state had not received prenatal HIV testing.34 Second, we defined any patient who did not fulfill criteria for being HIV positive and ever had a negative HIV test as being HIV negative. However, because we are unable to account for patients' HIV risk behaviors occurring after a negative HIV test, we are underestimating the proportion of those who truly have unknown HIV status and may be at risk of undiagnosed HIV. Finally, we examined how a limited number of demographic characteristics were associated with unknown HIV status. Although we restricted this analysis to those patients who had prior contact with our health care system, we did not distinguish between different types of contact (eg, prior ED visit versus prior inpatient admission versus prior outpatient visit) or the frequency or patterns of contact that we suspect are important determinants of having an unknown HIV status.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated how ascertaining the prevalence of unknown HIV status can inform expanded HIV-testing strategies. Despite a decreasing trend in the proportion of patients with unknown HIV status, in 2011, 75% of unique ED patients aged 13 and older still had unknown HIV status and therefore remain at risk for undiagnosed HIV. Furthermore, specific demographic characteristics are associated with having unknown HIV status. Understanding the prevalence of unknown HIV status, locating it in the context of a secular trend, and relating it to specific demographic characteristics will inform the further design and implementation of expanded HIV-testing strategies.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding Sources/ Disclosures: This study was supported in part by the Center for AIDS Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center (NIH AI-51519); HIV Prevention Trial Network study 065 (UM1 AI06819); NIH R25DA023021; NIH R01DA032110; NIH R34DA031066; and CTSA grants UL1RR025750, KL2RR025749, and TL1RR025748 from the NCRR, a component of the NIH.

Footnotes

Authors' Note: Aspects of the work were presented in poster format at the XIX International AIDS Conference in Washington DC in July 2012 as well as in poster and oral format at the 2012 National Summit on HIV and Viral Hepatitis Diagnosis, Prevention, and Access to Care in Washington DC in November 2012.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data– United States and 6 U.S. dependent areas–2010. HIV Surveill Suppl Rep. 2012;17(no.3, part A) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palella FJ, Jr, Deloria-Knoll M, Chmiel JS, et al. Survival benefit of initiating antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons in different CD4+ cell strata. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):620–626. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chadborn TR, Delpech VC, Sabin CA, Sinka K, Evans BG. The late diagnosis and consequent short-term mortality of HIV-infected heterosexuals (England and Wales, 2000-2004) AIDS. 2006;20(18):2371–2379. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801138f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV surveillance–United States, 1981-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(21):689–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS. 2006;20(10):1447–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkins TC, Gardner EM, Thrun MW, Cohn DL, Burman WJ. Risk-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing fails to detect the majority of HIV-infected persons in medical care settings. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(5):329–333. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000194617.91454.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV infection–South Carolina, 1997-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(47):1269–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goetz MB, Hoang T, Bowman C, et al. A system-wide intervention to improve HIV testing in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1200–1207. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0637-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Results of the Expanded HIV Testing Initiative–25 jurisdictions, United States, 2007-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(24):805–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyss SB, Branson BM, Kroc KA, Couture EF, Newman DR, Weinstein RA. Detecting unsuspected HIV infection with a rapid whole-blood HIV test in an urban emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(4):435–442. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f83d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown J, Shesser R, Simon G, et al. Routine HIV screening in the emergency department using the new US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines: results from a high-prevalence area. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(4):395–401. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181582d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Conroy AA, et al. Routine opt-out rapid HIV screening and detection of HIV infection in emergency department patients. JAMA. 2010;304(3):284–292. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merchant RC, Seage GR, Mayer KH, Clark MA, DeGruttola VG, Becker BM. Emergency department patient acceptance of opt-in, universal, rapid HIV screening. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(suppl 3):27–40. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calderon Y, Leider J, Hailpern S, et al. High-volume rapid HIV testing in an urban emergency department. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(9):749–755. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudepohl NJ, Lindsell CJ, Hart KW, et al. Effect of an emergency department HIV testing program on the proportion of emergency department patients who have been tested. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(supplement 1):S140–S144. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuter J, Alpert PL, DeShaw MG, Greenberg B, Klein RS. Rates of and factors associated with self-reported prior HIV testing among adult medical patients in an inner city emergency department in the Bronx, New York City. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1997;14(1):61–66. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199701010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merchant RC, Catanzaro BM, Seage GR, III, et al. Demographic variations in HIV testing history among emergency department patients: implications for HIV screening in US emergency departments. J Med Screen. 2009;16(2):60–66. doi: 10.1258/jms.2009.008058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Ruffner AH, Trott AT, Fichtenbaum CJ. Relationship of self-reported prior testing history to undiagnosed HIV positivity and HIV risk. Curr HIV Res. 2009;7(6):580–588. doi: 10.2174/157016209789973646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myers JE, Braunstein SL, Shepard CW, et al. Assessing the impact of a community-wide HIV testing scale-up initiative in a major urban epidemic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(1):23–31. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182632960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenness SM, Murrill CS, Liu KL, Wendel T, Begier E, Hagan H. Missed opportunities for HIV testing among high-risk heterosexuals. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):704–710. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181ab375d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albrecht E, Frascarolo P, Meystre-Agustoni G, et al. An analysis of patients' understanding of ‘routine’ preoperative blood tests and HIV screening. Is no news really good news? HIV Med. 2012;13(7):439–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutchinson AB, Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Mohanan S, del Rio C. Understanding the patient's perspective on rapid and routine HIV testing in an inner-city urgent care center. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16(2):101–114. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.2.101.29394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH) New York City HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics 2012. [Accessed December 8, 2013]; Web site. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/data/hivtables.shtml. Published 2012. Updated January 2015.

- 25.Torian LV, Wiewel EW. Risk factors for concurrent diagnosis of HIV/AIDS in New York City, 2004: the role of age, transmission risk, and country of birth; 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2007; February 25-28, 2007; Los Angeles, California. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH) The Bronx Knows HIV Testing Initiative: Final Report. [Accessed December 1, 2014];2012 Web site. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/ah/bronx-knows-summary-report.pdf. Published 2012.

- 27.Donnell DJ, Hall HI, Gamble T, et al. Use of HIV case surveillance system to design and evaluate site-randomized interventions in an HIV prevention study: HPTN 065. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:122–130. doi: 10.2174/1874613601206010122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.New York State Department of Health (NYS DOH) Frequently asked questions regarding the HIV testing law. [Accessed December 10, 2014];2010 Web site. https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/providers/testing/law/faqs.htm. Published 2010. Updated September 2013.

- 29.Felsen UR, Bellin EY, Cunningham CO, Zingman BS. Development of an electronic medical record-based algorithm to identify patients with unknown HIV status. AIDS Care. 2014;26(10):1318–1325. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.911813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States, 2010. [Accessed November 16, 2014]; Web site. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf. Published 2010.

- 31.Moyer VA U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(1):51–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: HIV testing and diagnosis among adults–United States, 2001-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(47):1550–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du P, Camacho F, Zurlo J, Lengerich EJ. Human immunodeficiency virus testing behaviors among US adults: the roles of individual factors, legislative status, and public health resources. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(9):858–864. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31821a0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.New York State Department of Health (NYS DOH) Prevention of perinatal transmission: maternal-pediatric HIV prvention and care program. [Accessed November 12, 2014];2012 Web site. http://www.health.ny.gov/dis-eases/aids/about/perinatal.htm. Published 2012. Revised October 2013.