Introduction

Management of arcuate anomaly of the uterus has always been a dilemma in the field of reproductive treatments. The balance of the existing publications does not support an association of the arcuate uterus with adverse reproductive outcome [1]. This lack of consensus is probably due to the different diagnostic modalities used and the different criteria for defining this phenomenon [2].

Based on our observations that most parous women show increased myometrial thickness similar with those of women with pregnancy loss, we conducted a study to clarify whether an arcuate uterus really is a risk factor for pregnancy loss.

Clinical Aspect

Women referred for fertility treatment were prospectively recruited. Three groups were constructed: Group 1 consisted of all nulligravid patients excluding tubal pathology, male factor, endometriosis and systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus; group 2 included patients with a history of ≥1 pregnancy losses; and group 3 comprised patients who had a history of ≥1 spontaneous pregnancies with healthy outcomes.

All patients underwent a transvaginal ultrasound scan as part of their standard assessment. Measurements of the fundal myometrial thickness (Fm) and cornual myometrial thickness (Cm) were taken using saline infusion sonography (SIS) as part of the women’s routine examination.

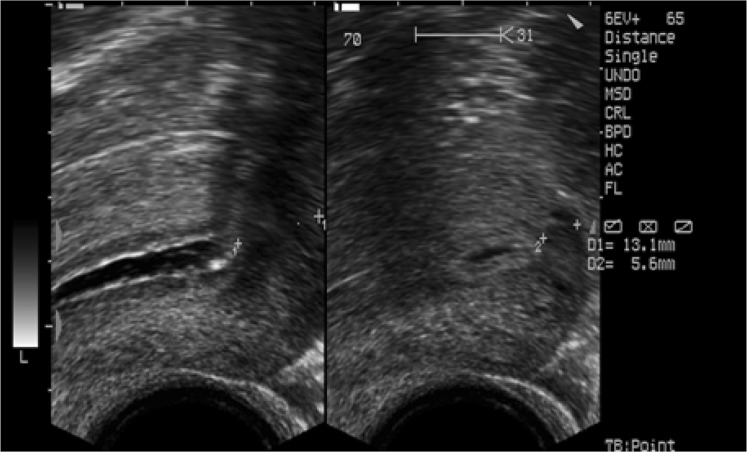

Fm was measured at the midsagittal plane, while Cm was measured where the myometrium appeared to be the thinnest (Fig. 1). Coronal sections were also evaluated for a double-cavity appearance (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound image showing the planes where Fm and Cm were measured

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound image showing the assessment of double-cavity appearance at coronal section

Fm and Cm were significantly thicker in group 3 compared with group 1 and group 2 (p < 0.05) (Table 1). There was a tendency toward a thicker Fm as the number of the abortions increased, but it did not reach a statistically significant level (Table 2). Group 3 was further analyzed as subgroups: group 3a (history of 1 healthy delivery); group 3b (history of 2 healthy deliveries); and group 3c (history of ≥3 healthy deliveries). We found a significantly thicker Fm in group 3c compared with group 3b (Table 3).

Table 1.

Saline infusion sonography findings of the groups

| Group I | Group II | Group III | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | 166 | 96 | 62 | NA |

| Mean age | 32.12 ± 6.91 | 33.3 ± 6.74 | 35.92 ± 5.59 | 0.001 (Gr1-2) |

| BMI | 24.45 ± 4.61 | 25.37 ± 5.51 | 24.22 ± 4.77 | 0.293 |

| Fm (cm) | 13.85 ± 3.60 | 14.13 ± 3.54 | 16.40 ± 3.40 | 0.000 (Gr1-3 Gr2-3) |

| Cm (cm) | 6.79 ± 1.90 | 7.24 ± 2.06 | 9.18 ± 2.07 | 0.000 (Gr1-3 Gr2-3) |

| Fm–Cm (cm) | 6.12 ± 3.09 | 6.16 ± 3.02 | 6.83 ± 3.38 | 0.388 |

| Double cavity | 34.67 % | 38.57 % | 46.51 % | 0.384 |

Table 2.

Saline infusion sonography findings of the subgroups in group II

| Group 2a History of 1 abortion |

Group 2 History of 2 abortions |

Group 2c History of >2 abortions |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | 70 | 19 | 7 | NA |

| Mean age | 32.70 ± 6.89 | 35.37 ± 5.77 | 33.71 ± 7.50 | 0.332 |

| BMI | 24.75 ± 4.98 | 28.22 ± 7.18 | 23.69 ± 2.71 | 0.153 |

| Fm (cm) | 13.80 ± 3.15 | 14.91 ± 3.94 | 15.37 ± 5.78 | 0.332 |

| Cm (cm) | 7.27 ± 1.70 | 7.12 ± 3.13 | 7.48 ± 1.35 | 0.816 |

| Fm–Cm (cm) | 5.72 ± 2.36 | 7.50 ± 3.88 | 6.45 ± 5.73 | 0.152 |

| Double cavity | 36.53 % | 53.33 % | 0 % | 0.964 |

Table 3.

Saline infusion sonography findings of the subgroups in group III

| Group3a History of 1 delivery |

Group 3b History of 2 deliveries |

Group 3c History of >2 deliveries |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | 48 | 12 | 2 | |

| Mean age | 36.15 ± 5.37 | 34.836.77 | 37.00 ± 5.66 | 0.563 |

| Husband’s age | 40.77 ± 6.78 | 37.92 ± 5.07 | 38.50 ± 4.95 | 0.334 |

| BMI | 24.34 ± 5.00 | 23.64 ± 4.20 | 26.70 ± 4.23 | 0.531 |

| Fm (cm) | 16.89 ± 3.28 | 14.30 ± 3.07 | 18.95 ± 1.77 | 0.013 Gr 3b-3c |

| Cm (cm) | 9.17 ± 2.04 | 9.21 ± 2.61 | 9.25 ± 0.35 | 0.789 |

| Fm–Cm (cm) | 7.47 ± 3.40 | 4.05 ± 1.55 | 9.70 ± 2.12 | 0.013 Gr3b-3c |

| Double cavity | 51.51 % | 12.5 % | 100 % |

Discussion

A man with a hammer in his hand may see everything as a nail. The ease of performing hysteroscopic procedures safely with contemporary instrumentation creates broad indications for mild forms of uterine abnormalities. Based on the widely accepted classification of the Mullerian abnormalities by American Fertility Society, arcuate uterus is thought to have no or minimal influence on the reproductive outcome [3] which means that it may be variation of a normal uterine anatomy not necessitating further treatment.

Although combined laparoscopic and hysteroscopic examination is considered the gold standard in diagnosis and classification of Mullerian abnormalities, less invasive tests, such as saline infusion sonography (SIS), have also proven to have high accuracy showing sensitivity and specificity of 93 and 99 %, respectively [1], and high diagnostic accuracy (94.0 %) [4].

Based on the findings in our study, we create a novel point of view to the issue of etiopathogenesis of arcuate uterus. We suggest that septate and subseptate uteri are absolutely congenital, while arcuate uterus seems to be the result of experiencing an intrauterine pregnancy regardless of the outcome of the gestation.

During pregnancy, the thickness of the muscular layer of the uterus increases mainly due to hypertrophy of existing myocytes, but partly to formation of new fibers. After pregnancy, the uterus nearly regains its size by the decrease in the volume and the total number of muscle cells, but the muscular layers remains thicker [5, 6]. It may be argued that the fundal myometrium appears thicker as it has more massive myocytes compared with cornual region.

Conclusion

Lack of well-designed randomized controlled trials keeps the relationship between arcuate uteri and pregnancy loss elusive. While waiting for the results of future randomized controlled trials, treatment decisions should be limited only to symptomatic patients who do not present any other identifiable etiology.

Mete Isikoglu

He obtained his medical degree in 1994 from Gulhane Medical School and had OB&GYN specialty training between 1996 and 2002 at Istanbul Medical Faculty. His current position is consultant IVF practitioner in GELECEK The Center For Human Reproduction, Antalya, Turkey. He has been in scientific committee of World Association of Reproductive Medicine (WARM), and he is a member of Antalya Chamber of Medicine, Turkish Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics, ESHRE and Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis International Society (PGDIS). He is also the national representative in European IVF Monitoring Consortium. He has many international and national publications and presentations. Also has given several international conferences and contributed nearly 15 textbook chapters. He acts as a peer reviewer for Fertility Sterility, European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, Reproductive Biomedicine Online, Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, International Journal of Fertility and Sterility and Turkish Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. He is especially interested in endoscopic surgery and holds the Bachelor in Endoscopy certificate given by European Academy of Gynaecological Surgery.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Mete Isikoglu is Specialist of Obstetrics and Gynecology, IVF Practitioner and Bachelor in Endoscopy at GELECEK The Center For Human Reproduction.

References

- 1.Saravelos SH, Cocksedge KA, Li TC. Prevalence and diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies in women with reproductive failure: a critical appraisal. Hum Reprod Update. 2008;14:415–429. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salim R, Jurkovic D. Assessing congenital uterine anomalies: the role of three-dimensional ultrasonography. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Fertility Society The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, mullerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:944–955. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59942-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ludwin A, Pityński K, Ludwin I, et al. Two- and three-dimensional ultrasonography and sonohysterography versus hysteroscopy with laparoscopy in the differential diagnosis of septate, bicornuate, and arcuate uteri. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(1):90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams PL, Warwick R, Dyson M, et al., editors. Uterine microstructure in Gray’s anatomy. 37. Harlow: Longman Group UK; 1989. pp. 1442–1443. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Leveno KJ, et al., editors. The puerperium in Williams obstetrics. 19. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall Int. Inc.; 1993. p. 459. [Google Scholar]