Abstract

In osteoporotic hip fractures, fracture collapse is deliberately allowed by commonly used implants to improve dynamic contact and healing. The muscle lever arm is, however, compromised by shortening. We evaluated a cohort of 361 patients with AO/OTA 31.A1 or 31.A2 intertrochanteric fracture treated by the dynamic hip screw (DHS) who had a minimal follow-up of 3 months and an average follow-up of 14.6 months and long term survival data. The amount of fracture collapse and shortening due to sliding of the DHS was determined at the latest follow-up and graded as minimal (<1 cm), moderate (1-2 cm), or severe (>2 cm). With increased severity of collapse, more patients were unable to maintain their premorbid walking function (minimal collapse = 34.2%, moderate = 33.3%, severe = 62.8%, and p = 0.028). Based on ordinal regression of risk factors, increased fracture collapse was significantly and independently related to increasing age (p = 0.037), female sex (p = 0.024), A2 fracture class (p = 0.010), increased operative duration (p = 0.011), poor reduction quality (p = 0.000), and suboptimal tip-apex distance of >25 mm (p = 0.050). Patients who had better outcome in terms of walking function were independently predicted by younger age (p = 0.036), higher MMSE marks (p = 0.000), higher MBI marks (p = 0.010), better premorbid walking status (p = 0.000), less fracture collapse (p = 0.011), and optimal lag screw position in centre-centre or centre-inferior position (p = 0.020). According to Kaplan-Meier analysis, fracture collapse had no association with mortality from 2.4 to 7.6 years after surgery. In conclusion, increased fracture collapse after fixation of geriatric intertrochanteric fractures adversely affected walking but not survival.

1. Introduction

Implants designed for fixation of osteoporotic hip fracture typically allow controlled sliding and collapse to improve bony contact and healing [1]. The dynamic hip screw (DHS) is one of the most widely used and successful implants for the treatment of stable intertrochanteric fractures with such design concept [2, 3]. Conversely, statically locked implants that aim at static fixation have yielded unacceptably high rate of failures for routine osteoporotic hip fractures because of the lack of dynamic compression and a lack of technical tolerance [4, 5]. Cephalomedullary fixation devices [6] and DHS with trochanter stabilizing plate [7] are effective means in preventing excessive collapse in unstable fractures (such as the AO/OTA type 31.A3 [8, 9]) but still much debated for routing use in more stable and intermediate patterns (such as types 31.A1 and A2).

Fracture collapse is sometimes associated with fixation failure [10] and believed to impair the hip abduction lever arm [11]. Researchers have pointed out that, for intracapsular hip fractures, increased fracture collapse accounted for poorer functional recovery [12, 13]. In young patients with trochanteric fractures, previous studies have shown that significant shortening of more than 2 cm is associated with impaired functional outcome [14] and previous studies have shown that DHS are associated with more pronounced shortening than cephalomedullary devices in young bone [14]. Currently, it has not been clearly studied whether collapse also adversely affects functional and survival outcomes for elderlies with trochanteric hip fractures.

Our objective was to test the hypothesis on whether patients with increasing degree of fracture collapse and shortening after DHS had impaired walking and increased incidence of adverse events. We carried out a secondary analysis of a consecutive prospective cohort of patients with trochanteric fractures treated with two similar DHS designs [15].

2. Patients and Methods

We reviewed a consecutive cohort of 433 patients with AO/OTA [8, 9] 31.A1 and 31.A2 fractures operated from 2007 to 2012 with DHS lag screws or DHS blades (both from formerly Synthes, Oberdorf, Switzerland). Only the cephalic portion of the implant differed and both were mounted on a standard nonlocked four-hole DHS slide plate. All included patients were over 50 years and patients with pathological fractures were excluded. Our hip fracture pathway [16] mandated surgical treatment as soon as possible unless the patient was medically unfit. A standard lateral subvastus approach was used for all patients on a traction table by closed or optional open assisted reduction. Patients followed a multidisciplinary rehabilitation protocol and were allowed immediate full weight bearing exercise. Upon follow-up, the functional status in walking and radiographs were analysed for collapse and complications.

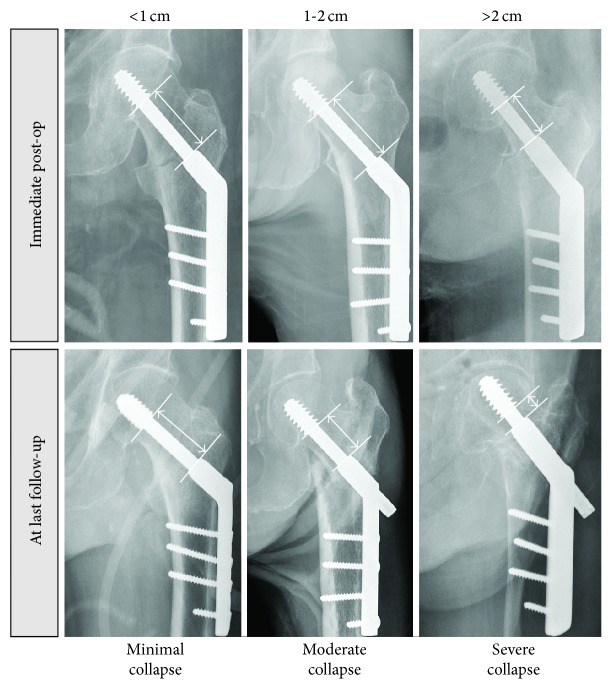

The degree of fracture collapse was determined by comparing the intraoperative and the latest anteroposterior radiograph. The remaining length of the lag screw or blade available for collapse was noted. The amount of collapse was determined at fracture union or at time of latest radiograph before any catastrophic mechanical failure. The degree of collapse was graded as minimal if this was not detectable when comparing the two radiographs or less than 1 cm, moderate if this was from 1 to 2 cm, and severe if this was more than 2 cm. The core diameter of the lag or the length of the side-plate barrel is used as reference dimensions to correct for the effects of magnification and rotation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Grading of severity of fracture collapse and shortening.

Perioperative patient, fracture, and surgical variables were compared for factors associated with different degree of collapse. These included age, gender, American Anesthesia Society (ASA) score, hours from admission to surgery (more than 48 hours versus less than 48 hours), Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) score [17], Modified Barthel Index [18] (MBI), surgeon experience (specialists with more than six years of experience versus trainees with less), and premorbid walking status. Walking status was graded as independent walker for those who did not require any assistance; assisted walkers if some degree of assistance was needed for activity of daily living; and nonfunctional walkers either if considerable assistance is needed or if the patient cannot walk at all. Implant position was defined as optimal if the fixation device was placed at the centre-centre or centre-inferior position of the femoral head; the tip-apex distance, as defined by Baumgaertner et al. [19], is optimal when less than 25 mm. Fracture reduction was defined according to Baumgaertner et al. [20] depending on the presence of a translation of more than 4 mm or varus of more than 5 degrees (good or acceptable reduction) or both (poor reduction).

The primary outcome was the best walking status achieved after rehabilitation using the same definition as the premorbid walking status. The premorbid walking grade was compared with postoperatively to determine whether there was a deterioration by one grade or more. The secondary outcomes were mortality, presence of complications including lateral wall fractures, implant migration in femoral head, cutout, side-plate pullout, nonunion, infection, and reoperations. Mortality data is recovered from the local territory wide electronic death registry, while survival is determined according to any patient attendance documented in the electronic public health care system which offers more than 90% territorial coverage.

SPSS software version 23 (IBM, Armonk NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The hips with collapse grades of minimal (1), moderate (2), and severe (3) degrees were designated as an ordinal variable and tested for associations. The Kruskal-Wallis test with Monte Carlo significance of 10000 random seeded samples was used for nonparametric variables and the one-way ANOVA test was used for parametric variables. Ordinal logistic regression was carried out firstly to identify independent factors which predicted increasing severity of fracture collapse and secondly to identify factors which predicted increased likelihood to walk well after rehabilitation. A p value of <0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Factors and Univariate Analysis

Patients who have died or were lost to follow-up before 3 months were excluded from analysis unless they were already documented to have moderate or severe degrees of fracture collapse. Out of the 433 total patients treated with a DHS, 354 patients had a radiological follow-up of at least 3 months and 7 additional patients had an earlier known moderate or severe collapse. In all, 361 patients fulfilled the analysis criteria.

Of the 361 patients, 319 (88.4%) had an X-ray taken after at least 6 months and 293 (81.2%) after at least 9 months. The mean radiological follow-up was 14.6 months. Definite survival or mortality data was recovered for 360 (99.7%) patients at the time of data analysis which was 2.4 to 7.6 years after surgery (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient selection and follow-up characteristics.

| Patients and follow-up characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total patients | % | n = 433 |

| Known moderate or severe collapse before 3 months | 1.6% | 7 |

| Adequate follow-up at 3 months | 81.8% | 354 |

|

| ||

| Fulfilled analysis criteria | 83.4% | 361 |

|

| ||

| Survival data available 2.4–7.6 years post-op | 99.7% | 360 |

| Had X-ray after 6 months | 88.4% | 319 |

| Had X-ray after 9 months | 81.2% | 293 |

Out of the 361 patients entered for analysis, 234 had minimal collapse, 84 had moderate collapse, and 43 had severe collapse. Out of the 43 patients with severe collapse, 20 patients had complete collapse where the lag screw or blade was touching the barrel and with no possibility for further collapse. This subgroup was, however, deemed too small for further analysis under a separate rank.

Patients with increasing severity of collapse were significantly older (mean age for minimal collapse = 83, moderate collapse = 82.6, severe collapse = 86, and p = 0.042), more likely suffered from A2 fractures (minimal = 40.2%, moderate = 65.5%, severe = 67.4%, and p = 0.000), and more likely had suboptimal tip-apex distance of more than 25 mm (minimal = 0%, moderate = 6%, severe = 0%, and p = 0.002) and poor reduction (minimal = 0.9%, moderate = 7.1%, severe = 18.6%, and p = 0.000) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Differences in baseline and outcome variables in relation to increasing severity of collapse.

| Baseline and surgical variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of collapse | Minimal | Moderate | Severe | p value | |||

| %/mean | n = 234 | %/mean | n = 84 | %/mean | n = 43 | ||

| Age at operation | 83 | (SD = 0.75) | 82.6 | (SD = 0.85) | 86 | (SD = 0.62) | 0.042 ∗ |

| Female versus males | 59.8% | 140 | 71.4% | 60 | 74.4% | 32 | 0.057 |

| 31.A2 versus A1 | 40.2% | 94 | 65.5% | 55 | 67.4% | 29 | 0.000 |

| Screw versus blade fixation | 54.7% | 128 | 58.3% | 49 | 46.5% | 20 | 0.461 |

| Premorbid nonfunctional walker | 6.8% | 16 | 9.5% | 8 | 2.3% | 1 | 0.531 |

| Premorbid assisted walker | 10.7% | 25 | 13.1% | 11 | 14.0% | 6 | |

| Premorbid independent walker | 81.2% | 190 | 77.4% | 65 | 83.7% | 36 | |

| Operation delayed more than 2 days after admission | 10.3% | 24 | 6.0% | 5 | 2.3% | 1 | 0.143 |

| MMSE score | 15.9 | (SD = 7.4) | 16.1 | (SD = 7.7) | 15.9 | (SD = 7.4) | 0.984∗ |

| Modified Barthel Index | 85.3 | (SD = 22.4) | 84.4 | (SD = 25.1) | 83.4 | (SD = 23.9) | 0.890∗ |

| ASA score 3 or above | 62.0% | 145 | 63.1% | 53 | 58.1% | 25 | 0.862 |

| Operated by trainees (<6 years of experience) | 31.6% | 74 | 29.8% | 25 | 30.2% | 13 | 0.941 |

| Operative time | 41.5 mins | (SD = 16.3) | 43.6 mins | (SD = 18.6) | 47.8 mins | (SD = 21.3) | 0.084∗ |

| Suboptimal centre-centre or centre-inferior lag screw position | 27.4% | 64 | 42.9% | 36 | 39.5% | 17 | 0.019 |

| Suboptimal tip-apex distance > 25 mm | 0.0% | 0 | 6.0% | 5 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.002 |

| Poor reduction (>4 mm translation and 5 degrees varus) | 0.9% | 2 | 7.1% | 6 | 18.6% | 8 | 0.000 |

| Acceptable reduction (>4 mm translation or 5 degrees varus) | 19.7% | 46 | 42.9% | 36 | 30.2% | 13 | |

| Good reduction (<4 mm translation and <5 degrees varus) | 79.5% | 186 | 50.0% | 42 | 51.2% | 22 | |

| Perfect reduction (<2 mm translation and no varus) | 59.4% | 139 | 35.7% | 30 | 30.2% | 13 | 0.000 |

|

| |||||||

| Outcomes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Walking function | |||||||

| Nonfunctional walker | 20.5% | 48 | 25.0% | 21 | 34.9% | 15 | 0.016 |

| Assisted walker | 26.9% | 63 | 22.6% | 19 | 34.9% | 15 | |

| Independent walker | 52.6% | 123 | 52.4% | 44 | 27.9% | 12 | |

| Unable to maintain walking function | 34.2% | 80 | 33.3% | 28 | 62.8% | 27 | 0.028 |

|

| |||||||

| Cumulative mortality | |||||||

| Died at 6 months | 2.1% | 5 | 1.2% | 1 | 2.3% | 1 | 0.880 |

| Died at 1 year | 8.5% | 20 | 8.3% | 7 | 2.3% | 1 | 0.377 |

| Died at 2 years | 22.2% | 52 | 19.0% | 16 | 16.3% | 7 | 0.628 |

|

| |||||||

| Complications | |||||||

| Lateral wall fractures | 2.1% | 5 | 21.4% | 18 | 55.8% | 24 | 0.000 |

| Any mechanical failure | 0.4% | 1 | 7.1% | 6 | 23.3% | 10 | 0.000 |

| Implant migration in femoral head | 0.4% | 1 | 4.8% | 4 | 11.6% | 5 | 0.001 |

| Hip joint penetration and cutout | 0.0% | 0 | 2.4% | 2 | 11.6% | 5 | 0.000 |

| Side plate pullout | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 2.3% | 1 | 0.111 |

| Nonunion | 0.0% | 0 | 1.2% | 1 | 16.3% | 7 | 0.000 |

| Infection | 0.4% | 1 | 0.0% | 0 | 4.7% | 2 | 0.053 |

| Reoperations | 0.9% | 2 | 2.4% | 2 | 11.6% | 5 | 0.002 |

Kruskal-Wallis test with Monte Carlo significance for nonparametric variables.

∗One-way ANOVA test for continuous variables.

A number of poor outcomes were significantly associated with the severity of collapse, including nonfunctional walking status after rehabilitation (minimal collapse = 20.5%, moderate = 25%, severe = 34.9%, and p = 0.016), inability to maintain premorbid walking function (minimal collapse = 34.2%, moderate = 33.3%, severe = 62.8%, and p = 0.028), and reoperations (minimal = 0.9%, moderate = 2.4%, severe = 11.6%, and p = 0.002).

A number of adverse radiological features or complications were more common in those with increasing severity of collapse, including lateral wall fractures (minimal = 2.1%, moderate = 21.4%, severe = 55.8%, and p = 0.000), implant migration in the femoral head (minimal = 0.4%, moderate = 4.8%, severe = 11.6%, and p = 0.001), hip joint cutouts (minimal = 0%, moderate = 2.4%, severe = 11.6%, and p = 0.000), and nonunions (minimal = 0%, moderate = 1.2%, severe = 16.3%, and p = 0.000).

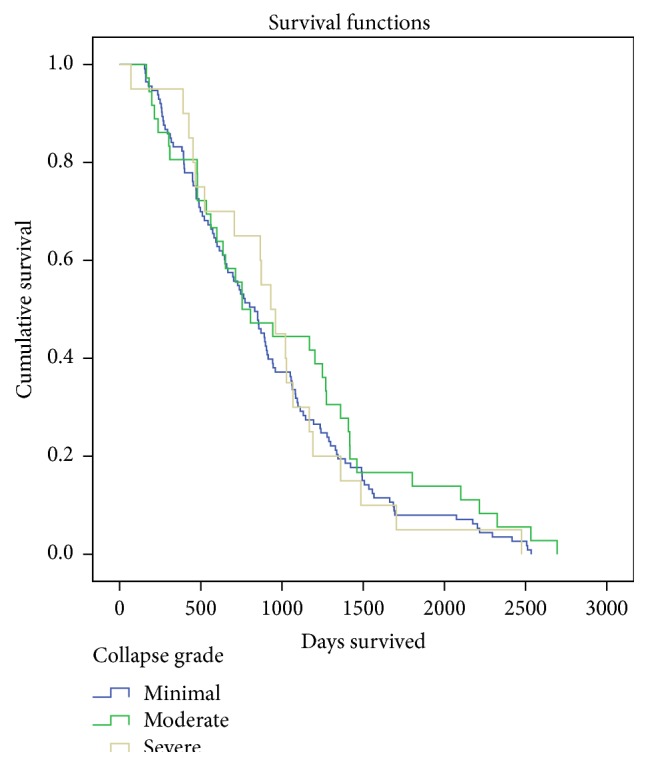

The mean survival of patients with minimal collapse was 916 days (95% CI: 807–1025), with moderate collapse it was 1025 days (95% CI: 794–1256), and with severe collapse it was 944 days (95% CI: 721–1196). Patients with increasing severity of collapse had no difference in survival up to 7.6 years after surgery in Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (log-rank test, p = 0.503) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot of patients with different grades of fracture collapse up to 7.6 years after surgery; there was no statistically significant difference between patients with different group of collapse (log-rank test, p = 0.503).

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

Based on ordinal regression, the independent risk factors for increased collapse were increasing age (p = 0.037), female sex (p = 0.024), 31.A2 fracture class (p = 0.010), increased operative duration (p = 0.011), poor reduction quality (p = 0.000), and suboptimal tip-apex distance of >25 mm (p = 0.050) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Ordinal regression of factors which predicted increasing severity of collapse. Value with a positive (+) estimate predicts more fracture collapse and that with a negative (−) estimate predicts less.

| Estimated likelihood of increased fracture collapse in ordinal regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard error | Wald | df | Sig. | 95% confidence interval | ||

| Per day delay from admission to operation | −0.121 | 0.191 | 0.401 | 1.000 | 0.527 | −0.496 | 0.254 |

| Operative time per minute increase | 0.021 | 0.008 | 6.484 | 1.000 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.037 |

| Age at operation per year increase | 0.049 | 0.023 | 4.369 | 1.000 | 0.037 | 0.003 | 0.095 |

| MMSE per mark increase | 0.025 | 0.023 | 1.182 | 1.000 | 0.277 | −0.020 | 0.071 |

| MBI per mark increase | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.701 | 1.000 | 0.402 | −0.009 | 0.023 |

| Poor premorbid walking status (independent versus assisted versus dependent) | −0.278 | 0.282 | 0.974 | 1.000 | 0.324 | −0.831 | 0.274 |

| Poor reduction quality (good versus acceptable versus poor) | 1.112 | 0.240 | 21.510 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.642 | 1.582 |

| Male versus female | −0.680 | 0.302 | 5.067 | 1.000 | 0.024 | −1.271 | −0.088 |

| 31.A1 class versus A2 | −0.719 | 0.281 | 6.570 | 1.000 | 0.010 | −1.269 | −0.169 |

| Screw versus blade | −0.156 | 0.284 | 0.301 | 1.000 | 0.583 | −0.712 | 0.401 |

| Operated by specialists (>6 years of experience) | 0.360 | 0.311 | 1.338 | 1.000 | 0.247 | −0.250 | 0.971 |

| Suboptimal centre-centre or centre-inferior lag screw position | 0.128 | 0.295 | 0.190 | 1.000 | 0.663 | −0.449 | 0.706 |

| ASA 1-2 versus 3-4 | 0.194 | 0.292 | 0.441 | 1.000 | 0.506 | −0.378 | 0.765 |

| Suboptimal tip-apex distance > 25 mm | 1.978 | 1.011 | 3.829 | 1.000 | 0.050 | −0.003 | 3.959 |

|

| |||||||

| Pseudo R-square (Nagelkerke) = 0.244 | |||||||

Ordinal regression also showed that significant factors which independently predicted better functional waking status after operation were younger age (p = 0.036), higher MMSE marks (p = 0.000), higher MBI marks (p = 0.010), better premorbid walking status (p = 0.000), less severe fracture collapse (p = 0.011), and optimal lag screw position in centre-centre or centre-inferior position (p = 0.020) (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Ordinal regression of factors which predicted better functional walking status after rehabilitation. Value with a positive (+) estimate predicts better walking status and that with a negative (−) estimate predicts a worse outcome.

| Estimated likelihood of having better walking function in ordinal regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Standard error | Wald | df | Sig. | 95% confidence interval | ||

| Per day delay from admission to operation | 0.069 | 0.194 | 0.126 | 1.000 | 0.722 | −0.311 | 0.448 |

| Operative time per minute increase | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.085 | 1.000 | 0.771 | −0.014 | 0.020 |

| Age at operation per year increase | −0.051 | 0.024 | 4.421 | 1.000 | 0.036 | −0.099 | −0.003 |

| MMSE per mark increase | 0.086 | 0.023 | 13.344 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.040 | 0.132 |

| MBI per mark increase | 0.021 | 0.008 | 6.587 | 1.000 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.037 |

| Poor premorbid walking status (independent versus assisted versus dependent) | 1.665 | 0.323 | 26.565 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.032 | 2.297 |

| Poor reduction quality (good versus acceptable versus poor) | 0.331 | 0.275 | 1.444 | 1.000 | 0.230 | −0.209 | 0.871 |

| Collapse grade (minimal versus moderate versus severe) | −0.650 | 0.256 | 6.445 | 1.000 | 0.011 | −1.151 | −0.148 |

| Male versus female | −0.213 | 0.292 | 0.530 | 1.000 | 0.467 | −0.786 | 0.360 |

| 31.A1 class versus A2 | 0.072 | 0.291 | 0.061 | 1.000 | 0.804 | −0.498 | 0.642 |

| Screw versus blade | −0.105 | 0.298 | 0.124 | 1.000 | 0.724 | −0.690 | 0.480 |

| Operated by specialists (>6 years of experience) | 0.090 | 0.321 | 0.078 | 1.000 | 0.780 | −0.540 | 0.719 |

| ASA 1-2 versus 3-4 | 0.280 | 0.306 | 0.840 | 1.000 | 0.359 | −0.319 | 0.880 |

| No mechanical failure | 0.787 | 0.684 | 1.326 | 1.000 | 0.250 | −0.553 | 2.127 |

| Not reoperated | 1.779 | 1.046 | 2.890 | 1.000 | 0.089 | −0.272 | 3.830 |

| No lateral wall fracture | −0.476 | 0.526 | 0.820 | 1.000 | 0.365 | −1.506 | 0.554 |

| Suboptimal tip-apex distance > 25 mm∗ | 22.688 | 0.000 | — | 1.000 | — | 22.688 | 22.688 |

| Suboptimal centre-centre or centre-inferior lag screw position | −0.695 | 0.299 | 5.392 | 1.000 | 0.020 | −1.282 | −0.108 |

|

| |||||||

| Pseudo R-square (Nagelkerke) = 0.504 | |||||||

∗Not enough valid cases to compute the significance of this item.

4. Discussion

In this study, it was demonstrated that fracture collapse was associated with poorer functional outcome, and this was independent of the patients' premorbid status. Moreover, complications occurred more commonly when patients had a more severe degree of collapse.

It is widely recognized in hip arthroplasty that shortening compromises the abductor muscle lever arm, resulting in weakness. In intracapsular neck of femur fractures, Zlowodzki et al. [12] studied 660 patients who have undergone screw fixation and concluded that a shortening of more than 10 mm resulted in significantly poorer short form 36 physical functioning scores compared to those with then 5 mm of shortening. Our study also suggests the same phenomenon to be true in geriatric intertrochanteric fractures, where increased fracture collapse indeed led to poorer walking function.

Our results showed that the independent risk factors for increased fracture collapse were old age, female sex, fracture comminution (31.A2 grading), increased operative time, poor fracture reduction quality, and suboptimal TAD. Of these factors, good fracture reduction appears to be of paramount importance. This is logical because doing so also effectively restores maximal contact of any available bony buttress [15, 21, 22]. For a dynamic device to work without excessive collapse, a majority of bone along the femur's circumference should remain intact and in contact. The well-known regions which provide effective bony support and load transfer between the main proximal and shaft fragments include the posterior medial calcar [23], the lateral wall [24], and the anteromedial region [25, 26]. As such, severe angulation, medialization of the proximal fragment [27], and lateral wall fractures [28, 29] result in a loss of bony support, and excessive fracture collapse.

Older female patients are more likely to have poor bone quality and reduced resistance to fracture collapse. A2 fractures are more comminuted and less stable than A1 fractures. As shown here, these patients were more likely to have eventual collapse. Fractures that required increased operative time also had increased likelihood of collapse. However, we are unable to conclude on whether it is prolonged operation itself or difficult fracture patterns which indirectly led to increased fracture collapse.

A number of studies have already pointed out the importance of implant position on outcomes. This was not consistency reproduced in our results possibly because of the low occurrences of poor TAD and poor implant positioning. Good implant positioning is known to be best determined by a small tip-apex distance of less than 25 mm and centre-centre or centre-inferior positioning of the lag screw in the femoral head in the AP and lateral radiographs [19, 22, 30, 31]. In all, surgeons must be meticulous with reduction and implant placement in trochanteric hip fractures while being mindful of risk factors such as osteoporosis and fracture comminution. The patients' functional outcome may be improved if precautions can be taken to limit the severity of fracture collapse.

There are a number of limitations to the study. Two slightly different implants were used in the group of patients, namely, as spiral blade and conventional lag screw. A standardized scoring system [32] was not used to grade functional outcomes because of the partially retrospective nature of data collection. We were not able to use an exact time point to define the patients' functional outcome as many of them suffered concomitant medical illness during or after rehabilitation and our study population had a highly variable timeline in recovery. We were unable to take pain into account in the clinical outcome analysis as we felt that there was poor documentation of this data in records. We were unable to find any verified grading system for the amount of collapse after DHS; nonetheless we felt that current method deemed simple enough and clinically applicable. The method through which we measured collapse of the metal implant may not always accurately reflect the true shortening between the bony fragments as an underestimation is likely in patients with implant migration in the femoral head.

The literature already contains many answered questions concerning improving patient survival and reducing complications. More research is needed to study how geriatric hip fracture patients can maintain better function. It is now evident that restoration and maintenance of the leg length is functionally important for both intracapsular [12, 13] and trochanteric hip fractures. Future implant design and improvements in treatment principles should take such findings into consideration.

5. Conclusion

Femoral shortening and collapse after DHS fixation are predisposed by old age, female sex, fracture comminution, poor reduction, and suboptimal implant placement. While the DHS is designed to allow for sliding and some degree of fracture collapse, those with severe collapse are more prone to eventual mechanical failure and complications. Increased collapse adversely affected patients' function in walking but did not appear to impair their survival.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Olsson O., Ceder L., Hauggaard A. Femoral shortening in intertrochanteric fractures—a comparison between the Medoff sliding plate and the compression hip screw. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery—British Volume. 2001;83(4):572–578. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b4.11302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton T. M., Gleeson R., Topliss C., Greenwood R., Harries W. J., Chesser T. J. S. A comparison of the long gamma nail with the sliding hip screw for the treatment of AO/OTA 31-A2 fractures of the proximal part of the femur: a prospective randomized trial. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery—American Volume. 2010;92(4):792–798. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.i.00508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker M. J., Handoll H. H. G. Gamma and other cephalocondylic intramedullary nails versus extramedullary implants for extracapsular hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000093.pub4.CD000093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkes M. B., Little M. T. M., Lazaro L. E., Cymerman R. M., Helfet D. L., Lorich D. G. Catastrophic failure after open reduction internal fixation of femoral neck fractures with a novel locking plate implant. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2012;26(10):e170–e176. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31823b4cd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider K., Zderic I., Gueorguiev B., Richards R. G., Nork S. E. What is the underlying mechanism for the failure mode observed in the proximal femoral locking compression plate? A biomechanical study. Bone & Joint Journal Orthopaedic Proceedings Supplement B. 2014;96(supplement 11):p. 130. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pajarinen J., Lindahl J., Michelsson O., Savolainen V., Hirvensalo E. Pertrochanteric femoral fractures treated with a dynamic hip screw or a proximal femoral nail: a randomised study comparing post-operative rehabilitation. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery—British Volume. 2005;87(1):76–81. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.c.01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babst R., Renner N., Biedermann M., et al. Clinical results using the Trochanter Stabilizing Plate (TSP): the modular extension of the Dynamic Hip Screw (DHS) for internal fixation of selected unstable intertrochanteric fractures. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 1998;12(6):392–399. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199808000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsh J. L., Slongo T. F., Agel J., et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium—2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association Classification, Database and Outcomes Committee. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2007;21(10):S1–S6. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200711101-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pervez H., Parker M. J., Pryor G. A., Lutchman L., Chirodian N. Classification of trochanteric fracture of the proximal femur: a study of the reliability of current systems. Injury. 2002;33(8):713–715. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker M. J., Khan R. J. K., Crawford J., Pryor G. A. Hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly: a randomised trial of 455 patients M. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery—British Volume. 2002;84(8):1150–1155. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b8.13522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zlowodzki M., Jönsson A., Paulke R., Kregor P. J., Bhandari M. Shortening after femoral neck fracture fixation: is there a solution? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2007;461:213–218. doi: 10.1097/blo.0b013e31805b7ec4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zlowodzki M., Brink O., Switzer J., et al. The effect of shortening and varus collapse of the femoral neck on function after fixation of intracapsular fracture of the hip: a multi-centre cohort study. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery—British Volume. 2008;90(11):1487–1494. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.90b11.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weil Y. A., Khoury A., Zuaiter I., Safran O., Liebergall M., Mosheiff R. Femoral neck shortening and varus collapse after navigated fixation of intracapsular femoral neck fractures. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2012;26(1):19–23. doi: 10.1097/bot.0b013e318214f321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Platzer P., Thalhammer G., Wozasek G. E., Vécsei V. Femoral shortening after surgical treatment of trochanteric fractures in nongeriatric patients. Journal of Trauma—Injury, Infection and Critical Care. 2008;64(4):982–989. doi: 10.1097/ta.0b013e3180467745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang C., Lau T. W., Wong T. M., Lee H. L., Leung F. Sliding hip screw versus sliding helical blade for intertrochanteric fractures: a propensity score-matched case control study. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2015;97(3):398–404. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.97b3.34791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau T., Fang C., Leung F. The effectiveness of a geriatric hip fracture clinical pathway in reducing hospital and rehabilitation length of stay and improving short-term mortality rates. Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation. 2013;4(1):3–9. doi: 10.1177/2151458513484759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folstein M. F., Folstein S. E., McHugh P. R. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah S., Vanclay F., Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1989;42(8):703–709. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumgaertner M. R., Curtin S. L., Lindskog D. M., Keggi J. M. The value of the tip-apex distance in predicting failure of fixation of peritrochanteric fractures of the hip. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery—American Volume. 1995;77(7):1058–1064. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumgaertner M. R., Curtin S. L., Lindskog D. M. Intramedullary versus extramedullary fixation for the treatment of intertrochanteric hip fractures. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1998;(348):87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito J., Takakubo Y., Sasaki K., Sasaki J., Owashi K., Takagi M. Prevention of excessive postoperative sliding of the short femoral nail in femoral trochanteric fractures. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2015;135(5):651–657. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsueh K.-K., Fang C.-K., Chen C.-M., Su Y.-P., Wu H.-F., Chiu F.-Y. Risk factors in cutout of sliding hip screw in intertrochanteric fractures: an evaluation of 937 patients. International Orthopaedics. 2010;34(8):1273–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0866-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barton T. M., Gleeson R., Topliss C., Greenwood R., Harries W. J., Chesser T. J. S. A comparison of the long gamma nail with the sliding hip screw for the treatment of AO/OTA 31-A2 fractures of the proximal part of the femur: a prospective randomized trial. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery—American Volume. 2010;92(4):792–798. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.i.00508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu C.-E., Shih C.-M., Wang C.-C., Huang K.-C. Lateral femoral wall thickness. A reliable predictor of post-operative lateral wall fracture in intertrochanteric fractures. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2013;95(8):1134–1138. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.95b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang S., Zhang Y., Ma Z., Li Q., Dargel J., Eysel P. Fracture reduction with positive medial cortical support: a key element in stability reconstruction for the unstable pertrochanteric hip fractures. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2015;135(6):811–818. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2206-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim C.-G., Kweon S.-H., Han H.-J., Hwang J.-S. The antero-medial cortex overlapped reduction of unstable intertrochanteric fractures. Hip & Pelvis. 2013;25(4):280–285. doi: 10.5371/hp.2013.25.4.280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker M. J. Trochanteric hip fractures. Fixation failure commoner with femoral medialization, a comparison of 101 cases. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1996;67(4):329–332. doi: 10.3109/17453679609002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gotfried Y. The lateral trochanteric wall: a key element in the reconstruction of unstable pertrochanteric hip fractures. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2004;425:82–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palm H., Jacobsen S., Sonne-Holm S., Gebuhr P. Integrity of the lateral femoral wall in intertrochanteric hip fractures: an important predictor of a reoperation. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery—American Volume. 2007;89(3):470–475. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.f.00679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Bruijn K., den Hartog D., Tuinebreijer W., Roukema G. Reliability of predictors for screw cutout in intertrochanteric hip fractures. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery—American Volume. 2012;94(14):1266–1272. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.k.00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andruszkow H., Frink M., Frömke C., et al. Tip apex distance, hip screw placement, and neck shaft angle as potential risk factors for cut-out failure of hip screws after surgical treatment of intertrochanteric fractures. International Orthopaedics. 2012;36(11):2347–2354. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1636-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nordin E., Rosendahl E., Lundin-Olsson L. Timed ‘Up & Go’ test: reliability in older people dependent in activities of daily living—focus on cognitive state. Physical Therapy. 2006;86(5):646–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]