Highlights

-

•

We present a very rare case of acute Acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC).

-

•

Hepatitis C virus infection has not been documented as a cause of Cholecystitis.

-

•

Management of AAC mostly conservative, rarely need surgical intervention.

-

•

Understanding pathophysiology of AAC in crucial for the management.

Keywords: Acute Hepatitis C, Acute acalculous cholecystitis, case report

Abstract

Introduction

Acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC) is rarely encountered in clinical practice and has a high morbidity and mortality. AAC caused by viral hepatitis, with hepatitis A, B and EBV infections are rare, but well documented in the literature. Hepatitis C virus has not been reported as cause of AAC. This case report documents the first case of AAC associated with Acute Hepatitis C.

Presenting concerns

We present a 40 years old female with abdominal pain. She has a history of previous HCV infection. Her liver function tests were markedly deranged with elevated inflammatory markers. USS scan showed rather a very unusual appearance of an inflamed gallbladder with no gallstones and associated acute hepatitis, confirmed by an abdominal CT scan. HCV RNA PCR confirms flair up of the virus. The patient was managed conservatively in the hospital with follow up USS scan and Liver function tests showed complete recovery. Follow up HCV RNA PCR also returned to an undetectable level. The patient recovered completely with no adverse outcomes.

Conclusion

This case report is to the first to document the association between acute HCV and AAC. Despite being uncommon in western countries, viral hepatitis should be suspected as a causative agent of AAC, particularly when there is abnormal liver function test and no biliary obstruction.

1. Introduction

Acute cholecystitis is a common surgical problem. It is historically classified as either being of acute calculous or acalculous, with the former accounting for 90% of cases of acute cholecystitis. Diagnosis of acalculous cholecystitis is confirmed when acute gallbladder inflammation is not associated with gallstones or sludge, a rare condition that carries high morbidity and mortality [1]. It is associated with a variety of clinical conditions. The majority of cases occurs after surgical intervention (47%) with the remaining cases associated with prolonged immobilization, severe sepsis, and long-standing malnutrition [2], [3], [4].

Viral hepatitis is a rare cause of acalculous cholecystitis, with a handful of cases reported to be linked to hepatitis A, hepatitis B and EBV [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Up to date search to medline data base shows no reference to Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and its association to AAC. This case report document the first association between HCV and AAC and the challenge to confirm this association. This case report is complaint with CARE criteria as published in 2013 [19].

2. Presentation of case

A 40 years old female patient presented to the emergency department at Wanganui hospital, with a history of progressive upper abdominal pain, and nausea and vomiting for one week. She had also noticed increasing darker urine but no haematuria, no pale stools and no fevers.

She had a history of previous Hepatitis C infection, post-traumatic stress syndrome, anxiety and depression. She had no previous surgery. Her regular medications included Ritalin 150 mg daily, Clonazepam 4 mg daily, Zopiclone 7.5 mg daily. She had a history of previous intravenous drug abuse 20 years ago, as well as multiple skin piercings and tattoos. She lives at home with her husband and two children. She is a smoker of about 10–15 cigarettes per day for the past 15 years. No history of alcohol abuse.

On examination, she was acutely unwell, in severe pain which was poorly controlled with opioids, with a tachycardia of 110 beats/min and blood pressure of 110/70 mm Hg. Her temperature was 37.8 °C. She was clinically jaundiced, but had no signs of chronic liver disease. Abdominal examination showed a tender upper abdomen with percussion tenderness, mostly in the right upper quadrant (Positive Murphy sign), with an enlarged liver.

2.1. Diagnostic approach

Blood tests revealed normal WBC count of 8.9 × 109/L, slightly elevated CRP (40) on initial presentation, with thrombocytopenia (platelets count 77 × 109/L). Liver function tests indicated acute hepatitis, with total bilirubin of 155 μmol/L (normal 2–20), Alkaline Phosphatase 243 U/L (normal 20–29), ALT 2171 U/L (5–30), AST 1646 U/L (10–30), serum albumin 30 g/L (34–48), coagulation international normalized ratio-INR 1.3 (0.8–1.1). Pancreatic amylase was normal 15 U/L (8–53) and kidney function tests were also normal.

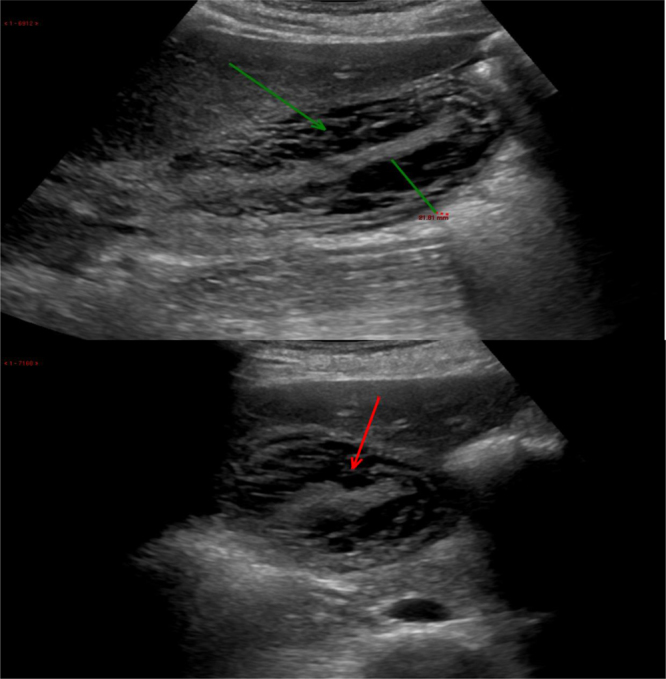

An abdominal ultrasound scan revealed moderate hepatomegaly with increased echogenicity, no focal lesions, normal calibre of common bile duct, with diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall (up to 20 mm) with lamellated hypoechoic appearance without gallstones and no peri-cystic fluid collection (Fig. 1). Vascular flow was demonstrated in the wall of gallbladder. Normal blood flow was seen in the portal vein, with no dilatation. Minimal ascites was present in the peritoneal cavity. These findings prompted further imaging with CT abdomen.

Fig. 1.

Transabdominal ultrasound scan showed diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall (up to 20 mm thick) with a lamellated hypoechoic appearance to the wall (arrow). The mucosa of gallbladder is seen in the middle of gallbladder with no lumen.

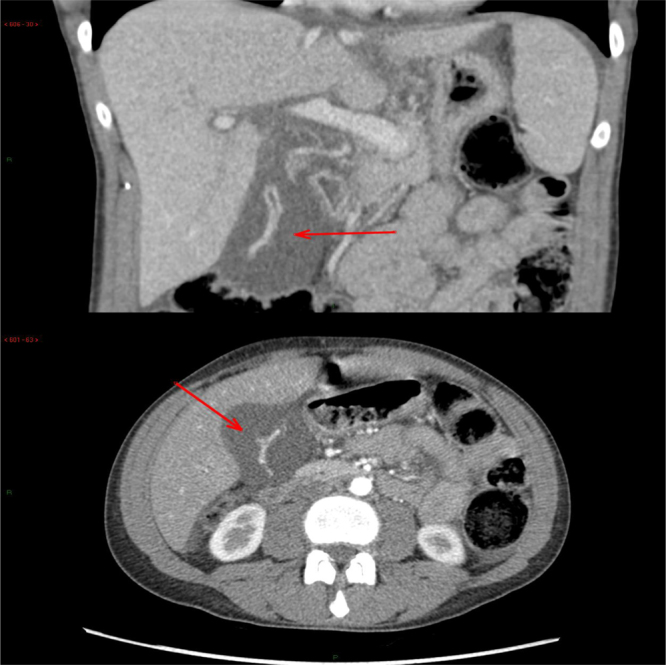

The abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast revealed an enhanced gallbladder mucosa with marked thickening of the wall, rather unusual radiological features of acutely inflamed gallbladder. There was also minimal peri-cystic fluid collection with increase density around the portal vein which was suggestive of oedema, likely due to acute hepatitis. A small amount of ascitic fluid was observed. (Fig. 2). The contrast perfusion of the liver in the arterial phase showed a geographic streaky hyperdensity in the right lobe of the liver, but homogeneous perfusion in the venous phase indicated hepatic perfusion in acute hepatitis. The liver was markedly enlarged, with no focal lesion. A normal spleen was seen.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal computerized tomography coronal and cross-sectional views showed the markedly enhanced gallbladder, with a markedly thickened and hypodense gallbladder wall. There was also a peri-cystic fluid collection and oedema around the portal vein branches with minimal ascites.

3. Treatment approach

The patient was admitted to the hospital, with interventions from the surgical, medical and mental health departments. Progression of clinical symptoms and signs of acute hepatic failure were monitored daily. Hepatitis C PCR (HCV RNA) test on admission, including genotyping, revealed a viral load of 113225 IU/mL(5.06 log IU/ml), genotype 1 A which previously had been undetectable. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) was also positive with a titre of 160. Anti-doublestrand DNA (ds-DNA) and ENA antibodies both tested negative.

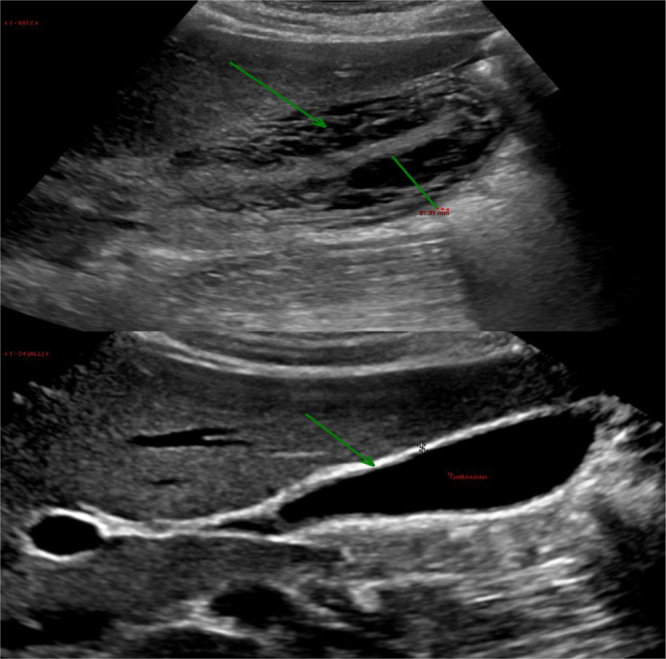

The patient had a dramatic clinical improvement with conservative management over a week, with improving pain and overall condition. The improvement also included the liver function tests, with bilirubin level returning to normal, INR returned to 1.1, and platelets count improved to 231 × 109/L. The patient was discharged home after a week with complete recovery, followed up by a hepatologist and the mental health team. A follow up USS scan after 6 weeks showed complete resolution of acute cholecystitis, a normal liver appearance, and no ascites (Fig. 3). A repeat HCV RNA PCR test after eight weeks showed no viral RNA detected. This confirms that the previous attack of AAC was related to an acute flare up of HCV.

Fig. 3.

Repeat ultrasound scan after 6 weeks showed complete resolution of gallbladder oedema and wall thickening. The gallbladder has returned to a normal appearance.

4. Discussion

Acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC) represents the inflammation of a gallbladder without evidence of gallstones. The condition is rare [12]. Complications such as perforation, gangrene formation, and empyema are the causes of the high morbidity and mortality associated with this condition [13]. The pathogenesis of AAC is yet to be studied due to its rare frequency. In one review of 15 patients with AAC, the primary pathological feature was vascular occlusion in the wall of the gallbladder secondary to over activation of factor XII-dependant coagulation pathway [15]. This process starts as gallbladder wall oedema that results in decreased perfusion, with necrosis of the wall of gallbladder if the process of inflammation continues. This inflammatory response is exacerbated by factors such as prolonged immobilization, starvation and sepsis, which reduces blood flow, resulting in gallbladder wall ischemic injury [16].

In addition to ischemic injury, cholecystokinin (CCK), an important hormone secreted after meals, could also play a role in the pathogenesis of AAC. CCK stimulates the gallbladder to contract and release the stored bile into the duodenum, which helps the emulsification of fatty food [18]. This action protects the gallbladder from the detergent effect of bile, which could lead to epithelial injury in cases of prolonged exposure [17]. In cases of starvation and immobilization, secretion of CCK is reduced significantly, eventually leading to bile stasis in the gallbladder and exposes the epithelium to the detergent effect of bile [16].

Viral hepatitis is a very rare cause of AAC and the pathophysiology is not fully understood. Low serum albumin, hepatomegaly due to acute inflammation, and high portal venous pressure may explain gallbladder wall oedema [14]. The most widely accepted hypothesis is ischemic injury of the gallbladder cells secondary to immune complex deposition, particularly in cases of ACC associated with hepatitis B virus infection [12]. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that up to 20% of acute hepatitis B patients develop extrahepatic complications secondary to immune complex deposition [18].

Hepatitis C-induced AAC has not been reported. In fact, our search on the MEDLINE database using the phrases ‘Hepatitis C’ and ‘acalculous cholecystits’ resulted in only one article titled “Hepatitis C virus infection revealed by an acute acalculous cholecystitis”- J. Radiol 2010 without further details about the case. This case report illustrates a very rare cause of AAC with clinical evidence of the disease and its association with Hepatitis C infection. We are confident that HCV is the cause of AAC in this case. The HCV RNA PCR confirms acute flare up of the virus followed by remission with improvement in the patient’s condition (Table 1).

Table 1.

Trend in liver function test over one week from acute attack of AAC.

| LFT | Day 1 | Day 3 | One week | Units | Ref. range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin | 155 | 176 | 20 | umol/L | 2–10 |

| Alk phosphatase | 243 | 226 | 122 | U/L | 20–90 |

| GGT | 94 | 68 | 21 | U/L | 10–35 |

| ALT | 2171 | 1262 | 74 | U/L | 5–30 |

| AST | 1646 | 551 | 44 | U/L | 10–30 |

| Total protein | 58 | 48 | 72 | g/L | 65–80 |

| Albumin | 30 | 23 | 33 | g/L | 34–48 |

The key factor in the management is conservative rather than surgical intervention, with no role for antibiotics in this case. This case also highlights the importance of screening for viral hepatitis when AAC is suspected, particularly when the liver function test is markedly deranged. Antiviral therapy was not given as the patient improved over short period of time with return of liver function and HCV PCR to normal levels. Liver biobsy was not considered as the LFT and HCV PCR returned back to normal.

Diagnostic challenge was to confirm that HVC was the cause of AAC in this case and to roll out the possibility of autoimmune disease, particularly with mild elevation in ANA level, but was deemed unlikely due to a weakly positive ANA. Furthermore, the patient did improve without steroids which also made an autoimmune cause very unlikely.

5. Conclusion

Previously, HBV and HAV have been documented as a cause of AAC but not HCV. In this case report, we have documented the association between acute HCV infection and AAC. Recommendation from this case report that viral hepatitis must be suspected as a cause of AAC, especially when Liver function test is markedly deranged and imaging exclude biliary obstruction. Treatment is conservative and antiviral treatment unlikely to be needed in such cases. However, further studies are required to evaluate weather antiviral treatment is required for better outcome.

Conflicts of interest

none.

Funding

No sources of funding needed for this case report.

Ethical approval

Fully Informed consent from the patient has been obtained, a copy attached. No ethical approval is needed for this case report.

Consent

Patient given fully informed consent and signed.

Author contribution

Authors did literature review, data collections, analysis and interpretation, writing the paper, reviewed the final version, provided the necessary care for the patient until discharged from the clinic.

Guarantor

Authors.

References

- 1.Shapiro M.J., Luchtefeld W.B., Kurzweil S. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in the critically ill. Am. Surg. 1994;60:335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glenn F., Becker C.G. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. An increasing entity. Ann. Surg. 1982;195(2):131–136. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198202000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard R.J. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Am. J. Surg. 1981;141(2):194–198. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(81)90155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonsson P.E., Andersson A. Postoperative acute acalculous cholecystitis. Arch. Surg. 1976;111(10):1097–1101. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1976.01360280055008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuoti M., Pinotti M., Miceli V., Villa M.C., Celano M.R., Amoruso C. Acute acalculous cholecystitis as a complication of hepatitis A: report of 2 paediatric cases. Pediatr. Med. Chir. 2008;30:102–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouyahia O., Khelifi I., Bouafif F., MazighMrad S., Gharsallah L., Boukthir S., Hepatitis A. a rare cause of acalculous cholecystitisin children. Med. Mal. Infect. 2008;38:34–35. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black M.M., Mann N.P. Gangrenous cholecystitis due to hepatitis Ainfection. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1992;95:73–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mourani S., Dobbs S.M., Genta R.M., Tandon A.K., Yoffe B. Hepatitis A virus-associated cholecystitis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994;120:398–400. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-5-199403010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozaras R., Mert A., Yilmaz M.H., Celik A.D., Tabak F., Bilir M. Acute viral cholecystitis due to hepatitis A virus infection. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2003;37:79–81. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200307000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeshita S., Nakamura H., Kawakami A. Hepatitis B related polyarteritisnodosa presenting necrotizing vasculitisin the hepatobiliary system successfully treated with lamivudine, plasmapheresis and glucocorticoid. Intern. Med. 2006;45(3):145–149. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black M.M., Mann N.P. Gangrenous cholecystitis dueto hepatitis A infection. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1992;95(1):73–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryu J.K., Ryu K.H., Kim K.H. Clinical features of acuteacalculouscholecystitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2003;36(2):166–169. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200302000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McChesney J.A., Northup P.G., Bickston S.J. Acuteacalculouscholecystitis associated with systemic sepsis andvisceral arterial hypoperfusion: a case series and review of pathophysiology. Digest. Dis. Sci. 2003;48(10):1960–1967. doi: 10.1023/a:1026118320460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klar A. Gallbladder and pancreatic involvement in hepatitisA. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1998;27(2):143–145. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199809000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glenn F., Becker C.G. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. An increasing entity. Ann. Surg. 1982;195:131–136. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198202000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warren B.L. Small vessel occlusion in acute acalculous cholecystitis. Surgery. 1992;111:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S.P. Pathogenesis of biliary sludge. Hepatology. 1990;12(3):S200–S203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohammed R.A., Ghadban W., Mohammed O. Acute acalculous cholecystitis induced by acute hepatitis B virus infection. Case Rep. Hepatol. 2012;2012:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2012/132345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagnier J., Kienle G., Altman D.G., Moher D., Sox H., Riley D.S., The CARE group The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013;67(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]