Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this study was to investigate occupational risk factors associated with bladder cancer.

Materials and Methods:

In this case–control study, control group included patients who referred to a specialized clinic in the same city and hospitals where patients had been registered. Data were entered into SPSS software. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated for occupational variables and other characteristics. Then, using logistic regression, the association between cancer and drugs was studied while smoking was controlled.

Results:

Cigarette smoking, even after quitting, was also associated with bladder cancer (OR = 2.549). Considering the classification of occupations, the OR of working in metal industry in patients was 10.629. Multivariate analysis showed that use of the drug by itself can be a risk factor for bladder cancer. Drug abuse together with the control of smoking increased the risk of bladder cancer by 4.959.

Conclusion:

According to the findings of this study, contact with metal industries such as welding, and working with tin was found as a risk factor for bladder cancer. In addition, cigarette smoking and opium abuse individually were associated with bladder cancer.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, cigarette, drugs, occupational factors, risk factors

Introduction

Nowadays, about 10% of deaths worldwide are due to cancers and it is estimated that the incidence of cancer worldwide would undergo an increasing trend.[1,2,3] Bladder cancer is a common cancer in the world.[3,4] Of cancers known and under investigation in the country, bladder cancer is ranked fifth,[5,6] however, in Kurdistan province it is ranked third in men and fourth in both sexes.[7,8] Overall, bladder cancer is the twelfth major cause of years of life lost due to premature death or disability per every 1000 people in Iran.[8]

This disease is more prevalent in industrial environments. Nowadays, it has been indicated that smoking and some occupational factors are the most important causes of bladder cancer; recognizing these factors will help to increase the possibility of intervention and risk reduction. Occupational and other risk factors may vary in different regions and it is necessary to check the occupational factors associated with various cancers in every area.[9] In a study in Isfahan it was revealed that drivers of heavy vehicles, farmers, metal industry workers, housewives, and construction workers are among high risk groups.[10] In Samanic et al.'s study, the odds ratio (OR) was calculated 5.6 for those with jobs related to publication, 1.6 for those involved in transportation, 3.9 for those involved in electrical jobs, and 2.1 for those working in manufacturing jobs.[11] Several studies have provided different results and there is a need for further investigation.[11,12]

Moreover, in some studies, the use of opium has been proposed as a risk factor for some cancers.[13,14,15] Using opium is very high in Iran and it is estimated that there are about two million opium users in the country.[16,17] As a result, the study of the relationship between substance abuse and bladder cancer may be effective in identifying risk factors; however, limited studies have been carried out in this area. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to evaluate risk factors for bladder cancer in the past 3 years in Kurdistan.

Materials And Methods

Design

This case–control study was approved by Ethic Committee of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences. Case group included all patients with bladder cancer who had been diagnosed histologically according to the International Classification of Diseases-10 by pathology laboratories and recorded in the cancer registry system[18] in Kurdistan province (west of Iran) during the past 3 years. Exclusion criteria were death and suffering from other cancers. An exclusion criterion for control group was cancer.

Sampling method

The names and address of patients were extracted via cancer registration software. Control group were chosen from patients who referred to a specialized clinic in the same city and hospitals where patients had been registered. During the visit to the clinic in the same city and hospitals, the people who were waiting in the waiting room for appointments by specialist were asked for permission to participate in the study and then the study objectives were explained to them. To select the control group, frequency matching was carried out in terms of age (±5 years), sex, and place of residency.

Tools

After taking permission and explaining the objectives of the study, a questionnaire was completed for every patient. Demographic characteristics and history of smoking and drug abuse were asked. Using the questionnaire, the employment status of the individual and the type of job activities over the last 20 years were asked. Interviews were conducted by trained personnels. Occupational classification was based on Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO 08),[19] and during conducting the interviews their most focused jobs were considered as individuals’ main occupation.

Data analysis

Data were entered into SPSS 16 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Using t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test, univariate analysis was conducted to compare the quantitative values in the two groups, and Chi-square and Fisher tests were used to compare the qualitative values in the two groups. Then, OR for occupational variables and exposure (with or without a history) and also the confidence intervals were calculated. Finally, using logistic regression, the association between cancer and drugs was studied while smoking was controlled.

Results

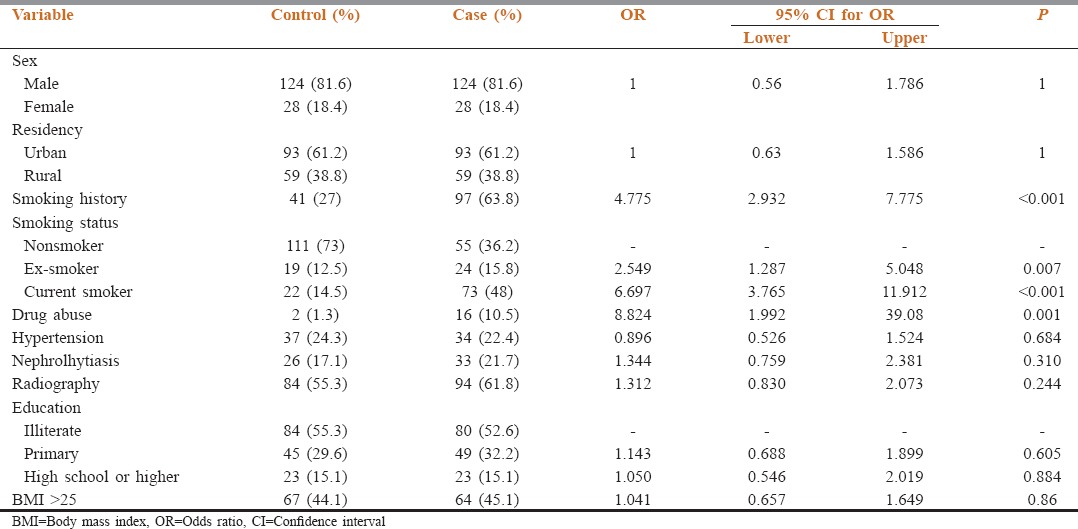

In this study, 152 patients with bladder cancer were examined from whom 124 patients (81.6%) were male and 28 (18.4%) were female. In the case group, 93 patients (61.2%) were urban and 59 persons (38.8%) were rural. The mean age of participants was 63.6 (±15.3) years in the group of patients with bladder cancer and 61.8 (±14.1) years in the control group (P = 0.288). In univariate analysis, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of the incidence of high blood pressure, kidney stones, undergoing radiography, literacy levels, and body mass index [Table 1].

Table 1.

Univariate analysis to compare the characteristics of cases and controls

Smoking history was significantly higher in the case group than the control group. Moreover, the history of drug abuse was significantly different between cases and controls (OR = 8.824). The OR for being affected by bladder cancer in active smokers (OR = 6.697) was higher than that of ex-smokers (OR = 2.549). All cases of drug addicts were abusing opium through smoking. Multivariate analysis showed that the use of drug by itself could be a risk factor for bladder cancer. Adjusted OR for smoking and opium were 4.29 (2.614–7.038) and 4.96 (1.073–22.924), respectively.

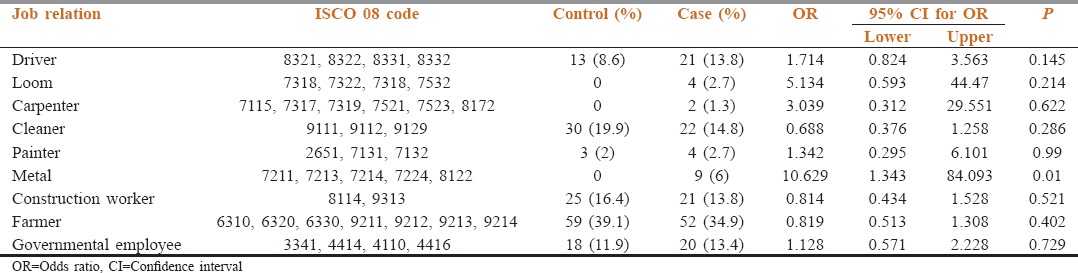

Considering the classification of occupations, the OR for patients working in metal industry was 10.629. However, none of the other occupations had a significant relationship with the bladder cancer [Table 2].

Table 2.

Univariate analysis to compare the occupations of the two groups of cases and controls

Discussion

Working with metal industries such as welding, and working with tin was found as a risk factor for bladder cancer. In addition, cigarette smoking and opium abuse individually were associated with bladder cancer. Other occupations were not associated with bladder cancer.

Until now, many studies have been conducted on the occupational risk factors associated with bladder cancer and in most of these studies there has been little findings to show a significant association between occupation and bladder cancer; in fact, the results of the studies has been different. Most studies just have found a weak level of association.[11,12] These differences are due to the fact that various jobs in different parts of the world may have different levels of exposure and they have not necessarily the same level of contact.

In Reulen et al.'s study[12] bladder cancer had a statistical significant associating with the occupation of mine workers, bus drivers, mechanics, beauticians, and leather related occupations, however, the levels of the associations were low. In Cassidy et al.'s study[9] working as servant, working in bars, and careers related to medicine and agriculture had a significant relationship with the occurrence of bladder cancer. In a study conducted in Egypt, agricultural jobs were identified as a job which was extremely associated with the high risk for bladder cancer.[20] Some studies have shown that working in agricultural jobs for more than 25 years increased the risk of bladder cancer.[21] Farmers and ranchers may have contact with chemicals that are carcinogenic. However, in recent years such types of exposure have had a decrease.[9] In Dryson et al.'s study[22] knitters and beauticians had a greater chance of developing bladder cancer, however, other jobs were not associated with bladder cancer.

Some studies also observed a relationship between bladder cancer and occupations related to metals (metal cutters, mechanics, and metal polishers),[23,24,25] though there are some other studies which did not have such a finding.[22] These people working in these jobs can have contact with aromatic amines which are used in cooling and lubricating oils. In some studies, working in electrical and electronics industry has been reported to be associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer.[9,26] Those working in these positions may experience other types of exposure which have not been studied yet.

Zeegers et al.'s study[27] showed that people who had contact with colors and painting, those who used aromatic amines, and individuals exposed to the vapors of diesel machines had an increased risk for bladder cancer. However, the associations were weak in their study. Some of the jobs in which individuals drink less liquid or have less time to urine may be associated with bladder cancer.[28]

People who use hair color can also be at risk.[29] Unfortunately, this issue was not investigated in our study. However, some other studies did not find a significant association between hair color use and bladder cancer[29,30,31] and this issue is still controversial.

In Baris et al.'s study,[32] people with a history of smoking were 3 times more at risk of bladder cancer and people who were smoking at that time were 5.2 times more at risk of bladder cancer. Their study, as in our study, showed a dose-dependent effect of smoking. Risks of smoking have been also shown in other studies.[33] Smoking is a risk factor for a variety of different cancers.

The evaluation of the effect of opium abuse in bladder cancer is a new issue that has recently been investigated on a few limited studies. According to the results of our study, opium abuse, could have a significant association with bladder cancer. In Ketabchi et al.'s study[14] it was found that the use of opium in patients with bladder cancer was higher than in the controls. Shakhssalim et al.'s study[34] also showed that opium abuse was a risk factor. Another study in Iran showed a link between the use of opium and bladder cancer and according to the results opium was associated with the incidence of invasive bladder cancer.[35] In our study, using regression analysis, the effect of smoking as a confounding factor was controlled and it was showed that opium abuse even without smoking may also be associated with bladder cancer. The opium effect mechanism could be similar to that of smoking, and the presence of impurities which may be carcinogenic could also be involved in this mechanism. Hydroxyphenanthrenes which is found in opium can also be a possible carcinogen and may lead to cancer development.[35]

Given the occupational mixes in Iran, the career mixtures may complicate the assessment of the risk factors associated with the each job. One of the limitations of this study was that it was not possible to assess occupational conduct blood or urine tests to demonstrate occupational exposure. Our study had other limitations as well. The control group was selected from a hospital which increases the possibility of Berkson's bias, because most jobs are risk factors for certain diseases that may increase the referral of patients to hospital. However, even in case of the incidence of such a bias, the results of this study may have underestimated the association between opium, smoking, and bladder cancer, and the association might even be stronger than the findings of the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all those who assisted us in the implementation of the research, and those who cooperated in performing the task are also appreciated. This study supported financially by deputy of research of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:765–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ploeg M, Aben KK, Kiemeney LA. The present and future burden of urinary bladder cancer in the world. World J Urol. 2009;27:289–93. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0383-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mousavi SM, Gouya MM, Ramazani R, Davanlou M, Hajsadeghi N, Seddighi Z. Cancer incidence and mortality in Iran. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:556–63. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A, Rachet B, Mitry E, Cooper N, Brown CM, Coleman MP. Survival from bladder cancer in England and Wales up to 2001. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(Suppl 1):S86–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esmailnasab N, Moradi G, Zareie M, Ghaderi E, Gheytasi B. Survey of epidemilogic status and incidence rates of cancers in the patients above 15 years old in Kurdistan province. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2007;11:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browning RM, Fellingham WH, O’Loughlin EJ, Brown NA, Paech MJ. Prophylactic ondansetron does not prevent shivering or decrease shivering severity during cesarean delivery under combined spinal epidural anesthesia: A randomized trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2013;38:39–43. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31827049c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassidy A, Wang W, Wu X, Lin J. Risk of urinary bladder cancer: A case-control analysis of industry and occupation. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:443. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pourabdian S, Janghorbani M, Khoubi J, Tahjvidi M, Mohebbi I. Relationship between high risk occupation particularly aromatic amines exposure and bladder cancer in Isfahan: A case-control study. Uromia Med J. 2010;21:222–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samanic CM, Kogevinas M, Silverman DT, Tardón A, Serra C, Malats N, et al. Occupation and bladder cancer in a hospital-based case-control study in Spain. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65:347–53. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.035816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reulen RC, Kellen E, Buntinx F, Brinkman M, Zeegers MP. A meta-analysis on the association between bladder cancer and occupation. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 2008;42:64–78. doi: 10.1080/03008880802325192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nasrollahzadeh D, Kamangar F, Aghcheli K, Sotoudeh M, Islami F, Abnet CC, et al. Opium, tobacco, and alcohol use in relation to oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a high-risk area of Iran. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1857–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ketabchi A, Gharaei M, Ahmadinejad M, Meershekari T. Evaluation of Bladder Cancer in Opium Addicted Patients in the Kerman Province, Iran, from 1999 to 2003. J Res Med Sci. 2005;10:355–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamangar F, Shakeri R, Malekzadeh R, Islami F. Opium use: An emerging risk factor for cancer? Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e69–77. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70550-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmadi J, Hasani M. Prevalence of substance use among Iranian high school students. Addict Behav. 2003;28:375–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziaaddini H, Ziaaddini MR. The household survey of drug abuse in Kerman, Iran. J Appl Sci. 2005;5:380–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safavi M, Honarmand A, Negahban M, Attari M. Prophylactic effects of intrathecal Meperidine and intravenous Ondansetron on shivering in patients undergoing lower extremity orthopedic surgery under spinal anesthesia. J Res Pharm Pract. 2014;3:94–9. doi: 10.4103/2279-042X.141105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amr S, Dawson R, Saleh DA, Magder LS, Mikhail NN, St George DM, et al. Agricultural workers and urinary bladder cancer risk in Egypt. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2014;69:3–10. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2012.719556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mannetje A, Kogevinas M, Chang-Claude J, Cordier S, González CA, Hours M, et al. Occupation and bladder cancer in European women. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:209–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1008852127139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dryson E, ’t Mannetje A, Walls C, McLean D, McKenzie F, Maule M, et al. Case-control study of high risk occupations for bladder cancer in New Zealand. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1340–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teschke K, Morgan MS, Checkoway H, Franklin G, Spinelli JJ, van Belle G, et al. Surveillance of nasal and bladder cancer to locate sources of exposure to occupational carcinogens. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:443–51. doi: 10.1136/oem.54.6.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kauppinen T, Toikkanen J, Pedersen D, Young R, Ahrens W, Boffetta P, et al. Occupational exposure to carcinogens in the European Union. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57:10–8. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calvert GM, Ward E, Schnorr TM, Fine LJ. Cancer risks among workers exposed to metalworking fluids: A systematic review. Am J Ind Med. 1998;33:282–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199803)33:3<282::aid-ajim10>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kogevinas M, ’t Mannetje A, Cordier S, Ranft U, González CA, Vineis P, et al. Occupation and bladder cancer among men in Western Europe. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:907–14. doi: 10.1023/b:caco.0000007962.19066.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeegers MP, Swaen GM, Kant I, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Occupational risk factors for male bladder cancer: Results from a population based case cohort study in the Netherlands. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58:590–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.9.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.’t Mannetje A, Pearce N. Bladder cancer risk in sales workers: Artefact or cause for concern? Am J Ind Med. 2006;49:175–86. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koutros S, Silverman DT, Baris D, Zahm SH, Morton LM, Colt JS, et al. Hair dye use and risk of bladder cancer in the New England bladder cancer study. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2894–904. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ros MM, Gago-Dominguez M, Aben KK, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Kampman E, Vermeulen SH, et al. Personal hair dye use and the risk of bladder cancer: A case-control study from The Netherlands. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1139–48. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9982-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendelsohn JB, Li QZ, Ji BT, Shu XO, Yang G, Li HL, et al. Personal use of hair dye and cancer risk in a prospective cohort of Chinese women. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1088–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baris D, Karagas MR, Verrill C, Johnson A, Andrew AS, Marsit CJ, et al. A case-control study of smoking and bladder cancer risk: Emergent patterns over time. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1553–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boffetta P. Tobacco smoking and risk of bladder cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 2008;42:45–54. doi: 10.1080/03008880802283664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shakhssalim N, Hosseini SY, Basiri A, Eshrati B, Mazaheri M, Soleimanirahbar A. Prominent bladder cancer risk factors in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:601–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hosseini SY, Safarinejad MR, Amini E, Hooshyar H. Opium consumption and risk of bladder cancer: A case-control analysis. Urol Oncol. 2010;28:610–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]