The structural implications of incorporating spectroscopic reporter unnatural amino acids into proteins is explored using X-ray crystallography. Four protein crystal structures with 4-cyano-l-phenylalanine or 4-ethynyl-l-phenylalanine incorporated into green fluorescent protein at two unique sites are described.

Keywords: 4-cyano-l-phenylalanine, 4-ethynyl-l-phenylalanine, unnatural amino acids, green fluorescent protein

Abstract

The X-ray crystal structures of superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP) containing the spectroscopic reporter unnatural amino acids (UAAs) 4-cyano-l-phenylalanine (pCNF) or 4-ethynyl-l-phenylalanine (pCCF) at two unique sites in the protein have been determined. These UAAs were genetically incorporated into sfGFP in a solvent-exposed loop region and/or a partially buried site on the β-barrel of the protein. The crystal structures containing the UAAs at these two sites permit the structural implications of UAA incorporation for the native protein structure to be assessed with high resolution and permit a direct correlation between the structure and spectroscopic data to be made. The structural implications were quantified by comparing the root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) between the crystal structure of wild-type sfGFP and the protein constructs containing either pCNF or pCCF in the local environment around the UAAs and in the overall protein structure. The results suggest that the selective placement of these spectroscopic reporter UAAs permits local protein environments to be studied in a relatively nonperturbative fashion with site-specificity.

1. Introduction

Unnatural amino acids (UAAs) have the potential to provide site-specific information about protein structure and dynamics (Getahun et al., 2003 ▸; Tucker et al., 2005 ▸; Schultz et al., 2006 ▸; Xie & Schultz, 2006 ▸; Aprilakis et al., 2007 ▸; Jackson et al., 2007 ▸; Glasscock et al., 2008 ▸; Oh et al., 2008 ▸; Weeks et al., 2008 ▸; Miyake-Stoner et al., 2009 ▸; Taskent-Sezgin et al., 2009 ▸, 2010 ▸; Waegele et al., 2009 ▸, 2011 ▸; Ye et al., 2009 ▸, 2010 ▸; Fafarman & Boxer, 2010 ▸; Goldberg et al., 2010 ▸; Urbanek et al., 2010 ▸; Nagarajan et al., 2011 ▸; Thielges et al., 2011 ▸; Bazewicz et al., 2012 ▸, 2013 ▸; Bagchi, Boxer et al., 2012 ▸; Peran et al., 2014 ▸; Petersson et al., 2014 ▸; Walker et al., 2014 ▸; Londergan et al., 2015 ▸; Tookmanian et al., 2015 ▸). Fundamentally, these spectroscopic reporter UAAs must contain a readily measurable spectroscopic signature that is sensitive to the local environment and must be able to be site-specifically incorporated into peptides or proteins with high efficiency and fidelity while being minimally intrusive. Even if a spectroscopic reporter UAA has a strong, sensitive, easily measurable spectroscopic observable and can be readily incorporated site-specifically into proteins, the utility of the reporter is diminished if the probe itself significantly alters the native protein environment under investigation.

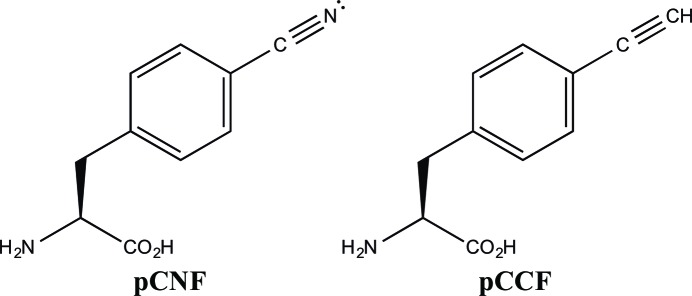

Numerous UAAs have been developed that contain spectroscopic probes designed to examine local protein environments (Xie & Schultz, 2006 ▸; Waegele et al., 2011 ▸). 4-Cyano-l-phenylalanine (pCNF; Fig. 1 ▸) is probably the most commonly utilized vibrational reporter UAA. In 2003, Gai and coworkers illustrated that the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration of this probe occurs in a relatively clear region of the infrared, has a relatively high extinction coefficient and is sensitive to local environment (Getahun et al., 2003 ▸). pCNF has been utilized as a vibrational reporter in both peptide and protein systems, where the UAA was incorporated by solid-phase peptide synthesis, semi-synthesis and/or nonsense-suppression methodologies (Getahun et al., 2003 ▸; Schultz et al., 2006 ▸; Fafarman & Boxer, 2010 ▸; Urbanek et al., 2010 ▸; Bazewicz et al., 2012 ▸).

Figure 1.

Structures of 4-cyano-l-phenylalanine (pCNF) and 4-ethynyl-l-phenylalanine (pCCF).

Recently, we have further extended the utility of 4-cyano-l-phenylalanine by the synthesis of isotopomers (13CN, C15N, 13C15N) of this UAA and incorporation of these UAAs site-specifically into the 247-residue monomeric β-barrel protein superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP; Pédelacq et al., 2005 ▸) utilizing an engineered, orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase with high efficiency and fidelity to probe various local environments present in the protein (Bazewicz et al., 2012 ▸). This work illustrated the ability to probe distinct local environments present in a protein system utilizing the frequency of the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration of pCNF. The isotopomers permit the unambiguous assignment of the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration of pCNF in proteins and provide the ability to probe multiple local protein environments simultaneously.

In addition to serving as a vibrational reporter UAA, 4-cyano-l-phenylalanine has the added characteristic that it can also function as a fluorescent spectroscopic reporter (Tucker et al., 2005 ▸; Aprilakis et al., 2007 ▸; Miyake-Stoner et al., 2009 ▸). This UAA forms a FRET pair with tryptophan with a Förster distance of 16.0 ± 0.5 Å (Tucker et al., 2005 ▸). Similarly, we have shown that 4-ethynyl-l-phenylalanine (pCCF; Fig. 1 ▸) is also a fluorescent spectroscopic reporter forming a FRET pair with tryptophan with a Förster distance of 15.6 ± 0.3 Å (Miyake-Stoner et al., 2009 ▸).

As noted above, an important characteristic of an effective spectroscopic reporter UAA is the ability to probe the local protein environment with minimal perturbations to the native protein structure. Previous work incorporating pCNF in the N-terminal domain of the L9 protein (NTL9) showed minimal perturbation of the overall structure based upon CD thermal denaturation experiments comparing protein stabilities of the wild-type protein and the protein constructs containing pCNF (Aprilakis et al., 2007 ▸; Taskent-Sezgin et al., 2009 ▸). In contrast, a recent study showed that the incorporation of pCNF in the N-terminal SH3 domain of the murine adapter protein Crk-II (nSH3) did alter the stability of the protein, as measured by thermal denaturation studies, where the site of incorporation impacted the extent of perturbation (Adhikary et al., 2014 ▸). Furthermore, the introduction of two pCNF residues simultaneously in the hydrophobic core of the 35-residue villin headpiece subdomain (Chung et al., 2011 ▸) and the individual incorporation of pCNF into two sites in the heme-binding pocket of cytochrome c (Zimmermann et al., 2011 ▸) also illustrated some structural perturbation as studied by denaturation measurements.

Here, we have utilized X-ray crystallography to examine the structural consequences of the incorporation of pCNF and pCCF into sfGFP at two sites with different local solvation environments with high resolution. Currently, only one protein crystal structure containing pCNF incorporated into the protein exists in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Fafarman & Boxer, 2010 ▸). In this structure, Fafarman and Boxer incorporated the UAA into a buried position in ribonuclease S using semi-synthesis (Fafarman & Boxer, 2010 ▸). The structure shows that the incorporation of this UAA is well tolerated. Similarly, Schultz and coworkers have shown that the incorporation of 4-iodo-l-phenylalanine (pIF) into the core of T4 lysozyme was well tolerated using X-ray crystallography (Xie et al., 2004 ▸). Structures of GFP or GFP analogues with different UAAs incorporated in the chromophore or elsewhere in the protein have also indicated limited structural perturbations (Bae et al., 2003 ▸; Wang et al., 2012 ▸; Niu & Guo, 2013 ▸; Reddington et al., 2013 ▸, 2015 ▸).

The current study expands upon these structures to assess the structural implication of pCNF and pCCF incorporated in two different solvation environments, a fully solvated and a partially buried site, in sfGFP utilizing X-ray crystallography. The UAAs were incorporated site-specifically utilizing nonsense-suppression methodologies. The sites in sfGFP selected in this study correspond to the sites previously used (Bazewicz et al., 2012 ▸) to examine the ability of pCNF and its isotopomers to probe local protein environments and allow a direct correlation between vibrational data and protein structure. pCCF was also incorporated at these sites to permit a direct comparison of the structure of sfGFP with these two different but similar spectroscopic reporter UAAs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. General information

Chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, PepTech, Research Products International and Hampton Research and were used without further purification. 4-Ethynylphenylalanine was synthesized as described previously (Miyake-Stoner et al., 2009 ▸). DH10B cells and pBADA were purchased from Invitrogen. All aqueous solutions were prepared with 18 MΩ-cm water.

2.2. Expression and purification of sfGFP constructs

The codons for Asp133 and Asn149 in a codon-optimized gene containing a C-terminal six-His affinity tag for wild-type sfGFP (wt-sfGFP; Pédelacq et al., 2005 ▸) were either individually or jointly replaced by site-directed mutagenesis with the amber stop codon (TAG), generating pBAD-sfGFP-133TAG, pBAD-sfGFP-149TAG and pBAD-sfGFP-133/149TAG, respectively. The aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase for the incorporation of either pCNF and pCCF was inserted into pDULE, generating pDULE-pCNF/pCCF (Miyake-Stoner et al., 2009 ▸). These plasmids were obtained from Dr Ryan A. Mehl (Oregon State University).

pBAD-sfGFP-133TAG, pBAD-sfGFP-149TAG and pBAD-sfGFP-133/149TAG were individually co-transformed with pDULE-pCNF/pCCF into DH10B Escherichia coli cells. The transformed cells were used to inoculate 5 ml noninducing media, which was grown to saturation while shaking (250 rev min−1) at 37°C. A 2.5 ml aliquot of the cultured cells was used to inoculate 250 ml autoinduction media containing either pCNF or pCCF at 1 mM per amber codon, except for negative-control experiments, in which the UAAs were excluded from the autoinduction media (Studier, 2005 ▸; Hammill et al., 2007 ▸). The cells from the autoinduction media were harvested by centrifugation after shaking at 37°C for 24–37 h and the expressed protein was purified using TALON cobalt ion-exchange chromatography (Clontech) similar to previous procedures (Miyake-Stoner et al., 2010 ▸; Smith et al., 2011 ▸; Bazewicz et al., 2012 ▸, 2013 ▸; Tookmanian et al., 2015 ▸).

The incorporation of pCNF into either site 133, site 149 or in both sites simultaneously in sfGFP resulted in the production of the protein constructs sfGFP-133-pCNF, sfGFP-149-pCNF and sfGFP-133/149-pCNF, respectively. The incorporation of pCCF into sites 133 and 149 in sfGFP simultaneously resulted in the production of the protein construct sfGFP-133/149-pCCF.

The purified proteins were desalted utilizing a PD10 gel-filtration column into a 20 mM HEPES aqueous buffer solution at a pH of 7.5. A catalytic amount of trypsin (1%) was added to cleave the C-terminal six-His affinity tag. The solution was incubated at 37°C for 2 h, resulting in a 239-residue protein (Pédelacq et al., 2005 ▸). The trypsin was then deactivated by the addition of phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) in a tenfold molar excess compared with trypsin. sfGFP resulting from incomplete six-His cleavage was removed by TALON cobalt ion-exchange chromatography. Excess PMSF was removed and the UAA-containing sfGFP construct was concentrated with a 10K molecular-weight cutoff Centricon (Millipore). All four of the purified protein constructs described here had a functional chromophore and were green.

2.3. Equilibrium FTIR measurements

The FTIR absorbance spectra of the sfGFP constructs were measured using a Bruker Vertex 70 FTIR spectrometer equipped with a globar source, KBr beamsplitter and a liquid-nitrogen-cooled mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector. The spectra were the result of 512 or 1024 scans recorded at a resolution of 1.0 cm−1 in a temperature-controlled transmission cell consisting of two calcium fluoride windows with a path length of ∼100 µm. The spectra were analyzed in Igor Pro (Wavemetrics).

2.4. Structure determination of sfGFP-133-pCNF

Purified sfGFP-133-pCNF was concentrated to 30 mg ml−1 in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and mixed in a 1:1 ratio with precipitant solution (22% PEG 3350, 2% Tacsimate pH 6, 0.1 M bis-tris pH 6.5) to form green crystals in a sitting-drop well at room temperature. Single crystals were mounted on loops, cryoprotected by consecutive soaks in 10, 18 and 25% ethylene glycol-supplemented precipitant solution and cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected on the NE-CAT 24-ID-E beamline at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) and processed in space group P21212 to 1.85 Å resolution using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▸). A molecular-replacement solution was determined using Phaser (Storoni et al., 2004 ▸; TFZ = 37) with wild-type sfGFP (PDB entry 2b3p; Pédelacq et al., 2005 ▸) in which residue 133 was replaced by an alanine as a search model. After a single round of refinement a phenylalanine was modelled into the 2F o − F c density at position 133, and following a few more rounds of refinement the CN group at the para position of the phenylalanine was modelled using the F o − F c difference density (Figs. 3a, 3b and 3c). Rounds of manual refinement in Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▸) and automated refinement in PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▸) were continued to produce the reported structure with an R and R free of 14.9 and 19.2%, respectively (Table 1 ▸).

Table 1. X-ray data-collection and refinement statistics.

| Crystal | sfGFP-133-pCNF | sfGFP-149-pCNF | sfGFP-133/149-pCNF | sfGFP-133/149-pCCF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P21212 | P61 | P21 | P21 |

| Unit-cell parameters | ||||

| a (Å) | 60.77 | 47.27 | 118.95 | 46.29 |

| b (Å) | 68.06 | 47.27 | 59.07 | 112.94 |

| c (Å) | 53.27 | 344.55 | 131.76 | 93.41 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 108.78, 90 | 90, 104.09, 90 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Unique reflections | 19485 | 81013 | 58961 | 119247 |

| Resolution range† (Å) | 50–1.85 (1.88–1.85) | 57–1.42 (1.45–1.42) | 50–2.54 (2.58–2.54) | 50–2.50 (2.54–2.50) |

| Average multiplicity† | 7.1 (7.2) | 36.9 (21.9) | 3.7 (3.7) | 1.9 (1.9) |

| Completeness† (%) | 99.7 (99.9) | 99.4 (94.7) | 100 (100) | 99.3 (98.9) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉† | 25.9 (2.9) | 45.1 (2.22) | 14.7 (1.8) | 10.9 (1.4) |

| R merge † | 6.5 (50.4) | 4.2 (127) | 10.9 (70.0) | 8.4 (54.8) |

| No. of sfGFP molecules per asymmetric unit | 1 | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| R cryst/R free ‡ (%) | 14.9 (19.2) | 18.0 (20.8) | 18.9 (24.4) | 18.0 (24.4) |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.150 | 1.245 | 1.272 | 1.524 |

| Ramachandran plot§ (%) | ||||

| Preferred | 97.36 (221) | 91.40 (404) | 95.44 (1257) | 94.43 (830) |

| Allowed | 2.64 (6) | 7.69 (34) | 3.87 (51) | 5.46 (48) |

| Outliers | 0 (0) | 0.90 (4) | 0.68 (9) | 0.11 (1) |

| PDB code | 5dpg | 5dph | 5dpi | 5dpj |

The value in parentheses is for the highest resolution shell.

R

cryst =

. R

free is calculated as for R

cryst but for a test set of reflections (5%) that were not included in refinement.

. R

free is calculated as for R

cryst but for a test set of reflections (5%) that were not included in refinement.

The numbers in parentheses are the number of residues in each category.

2.5. Structure determination of sfGFP-149-pCNF

Purified sfGFP-149-pCNF at a concentration of 17 mg ml−1 in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 was crystallized by mixing a 1:1 ratio of protein and precipitant (0.1 M Tris pH 8.5, 20% PEG 4000, 0.21 M MgCl2·6H2O) solutions in a sitting-drop well at room temperature. The green crystals were looped and cryoprotected by consecutive soaks in 5, 12 and 25% ethylene glycol-substituted precipitant solution and cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected on beamline 12-1 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) to 1.42 Å resolution and were processed in space group P61 using XDS (Kabsch, 2010 ▸). An initial structure solution containing two molecules in the asymmetric unit was determined in Phaser (Storoni et al., 2004 ▸; TFZ = 64) using the sfGFP structure (PDB entry 2b3p) with residue 149 replaced by alanine as a search model. The structure was further refined in the manner described for sfGFP-133-pCNF including the twin law h, −h − k, −l in PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▸). The reported structure was refined to an R and R free of 18.0 and 20.8%, respectively (Table 1 ▸). Interestingly, the electron density clearly showed that Glu222 was decarboxylated (see Supplementary Fig. S6) as has been observed in previous GFP structures (Bell et al., 2003 ▸; Adam et al., 2009 ▸; Henderson et al., 2009 ▸).

2.6. Structure determination of sfGFP-133/149-pCNF

Purified sfGFP-133/149-pCNF at a concentration of 28 mg ml−1 in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 was crystallized by mixing a 1:1 ratio of protein and precipitant (0.2 M potassium sodium formate, 30% PEG 3350) solutions in a sitting-drop well at room temperature. The green crystals were looped and cryoprotected by consecutive soaks in 8, 14 and 20% glycerol-substituted precipitant solution and cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected on the NE-CAT 24-ID-E beamline at APS to 2.56 Å resolution and processed in space group P21 using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▸). An initial structure solution containing six molecules in the asymmetric unit was determined in Phaser (Storoni et al., 2004 ▸; TFZ = 46) using the sfGFP structure (PDB entry 2b3p; Pédelacq et al., 2005 ▸) with residues 133 and 149 replaced by alanine as a search model. The structure was further refined in the manner described for sfGFP-133-pCNF in PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▸). The reported structure was refined to an R and R free of 18.9 and 24.4%, respectively (Table 1 ▸).

2.7. Structure determination of sfGFP-133/149-pCCF

Green crystals of purified sfGFP-133/149-pCCF were grown at room temperature by mixing equal volumes of 44 mg ml−1 protein solution in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 with a precipitant solution consisting of 22% PEG 3350, 0.20 M sodium citrate tribasic pH 7. The crystals were cooled in liquid nitrogen without cryoprotection. Diffraction data to 2.50 Å resolution were collected on the NE-CAT 24-ID-E beamline at APS. The data were indexed in space group P21 and processed in HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▸). A structure solution was found with four molecules in the asymmetric unit by molecular replacement using the wt-sfGFP structure (PDB entry 2b3p; Pédelacq et al., 2005 ▸) with residues 133 and 149 replaced by alanines as a search model in Phaser (Storoni et al., 2004 ▸; TFZ = 12). Rounds of manual and automated refinement were continued as described for sfGFP-133-pCNF to prevent model bias, where an ethynyl group was modeled instead of a cyano group at the para position of the phenylalanine (see Supplementary Fig. S4). A simulated-annealing composite OMIT map was calculated and built in towards the end of refinement to ensure that there was no model bias. The reported refined structure has an R and R free of 18.0 and 24.4%, respectively (Table 1 ▸).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural analysis of wt-sfGFP

Wild-type sfGFP is a 247-residue β-barrel monomeric protein (Pédelacq et al., 2005 ▸). The protein consists of 47% β-sheet and 10% helical structure. In this study, two sites were selected to represent two unique local environments at protein sites 133 and 149, which are natively an aspartic acid and an asparagine, respectively. The solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) for each of these sites was calculated using the GETAREA software (Fraczkiewicz & Braun, 1998 ▸) with a probe radius of 1.4 Å and with tyrosine instead of the native amino acids at both sites owing to the similar size of tyrosine and pCNF or pCCF. For comparison, the SASA of a fully solvated tyrosine residue in the random-coil tripeptide Gly-Tyr-Gly is 193 Å2. Residue 133 is located in a loop region of the protein and has a SASA of 170 Å2 or 88% solvent exposure compared with a fully solvated tyrosine residue. Residue 149 is located in a β-strand pointing towards solvent but shielded by neighboring side chains and has a SASA of 108 Å2 or 56% solvent exposure compared with a fully solvated tyrosine residue. Thus, the SASA calculations show that site 133 represents a fully solvated position in the protein while site 149 represents a partially buried (desolvated) position in the protein. The desolvation results from the position of the neighboring amino-acid side chains around this site.

3.2. Incorporation of pCNF and/or pCCF into site 133 and/or site 149 of sfGFP

The unnatural amino acids pCNF and pCCF were genetically incorporated into the fully solvated site 133 and/or the partially buried site 149 in sfGFP in response to an amber codon with high fidelity and site-specificity utilizing an engineered, orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. The fidelity of the UAA incorporation was verified by SDS–PAGE (Supplementary Fig. S1). In Supplementary Fig. S1, lanes 3–6 show that sfGFP-133-pCNF and sfGFP-149-pCNF were only produced when pCNF was present in the autoinduction media. Similarly, the sfGFP constructs containing two pCNF or pCCF UAAs were only produced when pCNF or pCCF, respectively, was present in the autoinduction media (Supplementary Fig. S1, lanes 7–10).

3.3. Sensitivity of pCNF to local solvation environments

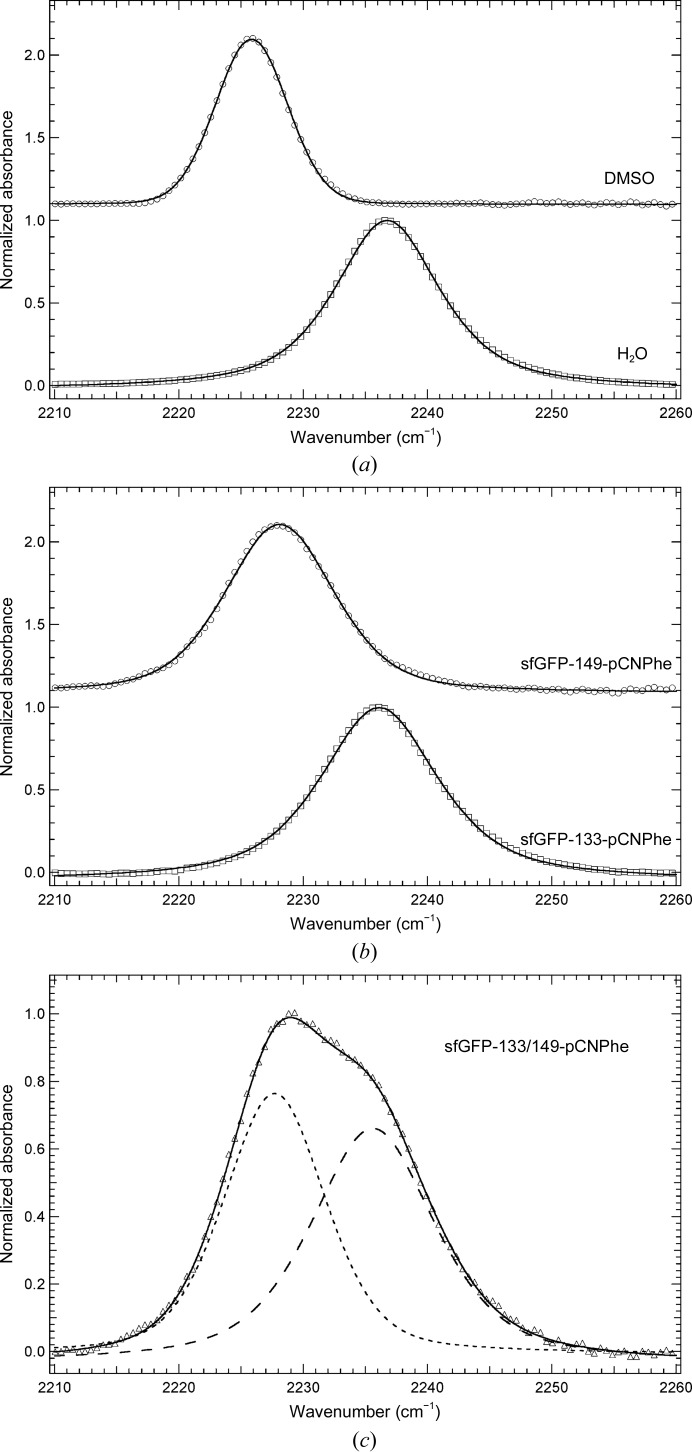

Fig. 2(a) ▸ shows that the IR absorbance band resulting from the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration of pCNF appears in a relatively clear region of the infrared and is relatively sharp and symmetrical. The IR spectra of pCNF were recorded in DMSO and an aqueous basic solution to mimic the hydrophobic and hydrophilic environments present in proteins, respectively. The nitrile symmetric stretch vibration of pCNF shifts from 2225.8 to 2236.7 cm−1 upon going from DMSO to water as the solvent, resulting in a blue shift of 10.9 cm−1, which is in agreement with previous measurements of the solvent-sensitivity of the nitrile symmetric stretching frequency of pCNF (Getahun et al., 2003 ▸). The observed blue shift going from DMSO to water is primarily the result of hydrogen bonding between the nitrile group of pCNF and water, as noted previously (Getahun et al., 2003 ▸; Bagchi, Fried et al., 2012 ▸). These results illustrate the ability of the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration to serve as a sensitive reporter of local environment.

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR absorbance spectra of pCNF dissolved in DMSO (empty circles) or an aqueous basic solution (empty squares) at a concentration of 50 mM. (b) FTIR absorbance spectra of sfGFP constructs containing pCNF incorporated at either site 149 (empty circles) or site 133 (empty squares) in the protein. (c) FTIR absorbance spectrum of pCNF incorporated at both site 149 and site 133 in the protein (empty triangles). The sfGFP constructs were dissolved in a pH 7.5 aqueous buffer containing 20 mM HEPES at a concentration of ∼1 mM. All spectra were recorded at 25°C, baseline corrected, intensity normalized and fitted (solid and dashed curves) to a linear combination of a Gaussian and Lorentzian functions.

Fig. 2 ▸(b) shows the FTIR absorbance spectra of sfGFP-133-pCNF and sfGFP-149-pCNF dissolved in a 20 mM HEPES aqueous buffer solution pH 7.5 in the region 2210–2260 cm−1. Both spectra show a single sharp and symmetrical absorbance band resulting from the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration of pCNF site-specifically incorporated into the protein. The position of this IR absorbance band is at 2236.1 and 2228.1 cm−1 for sfGFP-133-pCNF and sfGFP-149-pCNF, respectively (Fig. 2 ▸ b). The position of the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration in sfGFP-133-pCNF suggests that the nitrile group is solvated at this site. This assignment is based upon the similarity of this frequency to the frequency of the nitrile symmetric stretch of pCNF dissolved in water (2236.7 cm–1; Fig. 2 ▸ a). Analogously, the frequency of the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration in sfGFP-149-pCNF suggests that the nitrile group is partially buried at this site owing to the similarity of this frequency to that of pCNF dissolved in DMSO, which is a mimic of the hydrophobic environments present in proteins (2225.8 cm–1; Fig. 2 ▸ a). These results are consistent with the calculated SASA for these two residues and previous results for pCNF incorporated at these sites in sfGFP where the protein was dissolved in an aqueous buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM sodium chloride pH 7.3 (Bazewicz et al., 2012 ▸). The current spectra were recorded in HEPES buffer to mimic the conditions used in the crystallization of these constructs as described below.

Fig. 2 ▸(c) shows the FTIR absorbance spectrum of sfGFP-133/149-pCNF dissolved in 20 mM HEPES aqueous buffer solution pH 7.5 in the region 2210–2260 cm−1. The spectrum shows a single absorbance band that is comprised of at least two subcomponents (Fig. 2c ▸, dashed curves) resulting from the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration of pCNF incorporated into the protein. The central frequencies of the two components, as determined by line-shape analysis, are 2235.6 and 2227.7 cm−1 (Fig. 2c ▸, long-dashed and short-dashed curves, respectively), which are the result of the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration of pCNF at sites 133 and 149, respectively. The assignment is based upon the position of the vibrational frequency of the nitrile symmetric stretch vibration in sfGFP-133-pCNF and sfGFP-149-pCNF, respectively (Fig. 2 ▸ b). This result illustrates the ability of pCNF to probe two distinct local environments in sfGFP simultaneously .

3.4. Structural verification of site-specific UAA incorporation

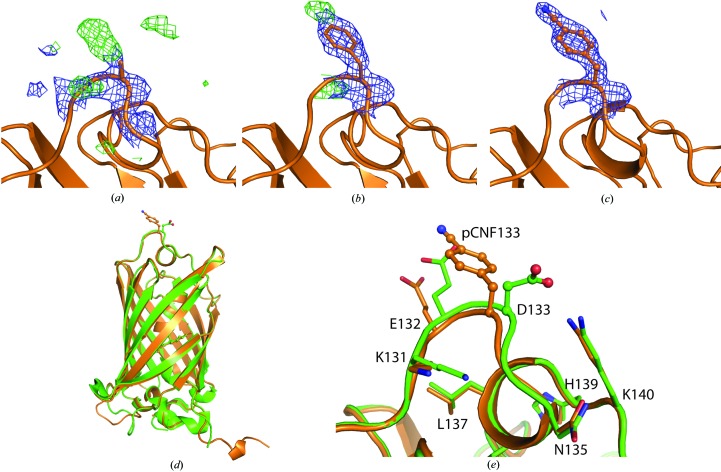

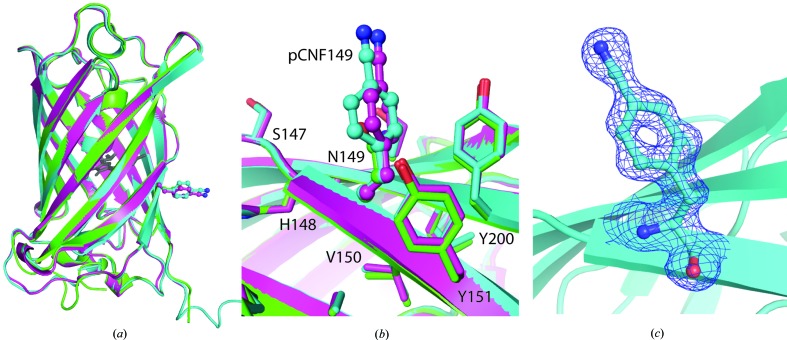

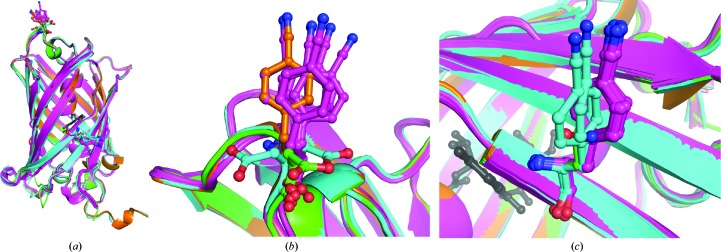

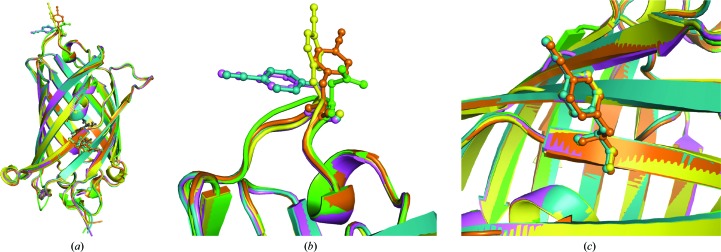

Here, we report the structures of sfGFP with pCNF incorporated individually at site 133 (Fig. 3 ▸) or 149 (Fig. 4 ▸) and at both sites 133 and 149 simultaneously (Fig. 5 ▸). We also report the structure of pCCF incorporated at both sites 133 and 149 simultaneously (Fig. 6 ▸) for comparison with the pCNF structures. Refinement of these structures indicates the incorporation of the UAA of interest at the desired location with occupancies refining to 100% for each residue. The refinement of the sfGFP-133-pCNF structure is shown in Figs. 3 ▸(a), 3 ▸(b) and 3 ▸(c), with the initial model of an alanine at this position, which was subsequently replaced by a phenylalanine and finally by 4-cyano-l-phenylalanine. This refinement sequence prevented any model bias from influencing the refinement and the 2F o − F c electron-density and F o − F c difference density maps clearly indicate the presence of the phenyl ring (Fig. 3 ▸ a) and cyano group at the para position of the phenyl ring (Figs. 3 ▸ b and 3 ▸ c). Similarly, the electron density in the other structures indicated the incorporation of pCNF at site 149 in sfGFP-149-pCNF (Fig. 4 ▸ c), pCNF at the 133 and 149 sites in sfGFP-133/149-pCNF (Supplementary Fig. S3) and pCCF at sites 133 and 149 in sfGFP-133/149-pCCF (Supplementary Fig. S4). The structures shown here highlight the fidelity of pCNF and pCCF incorporation, which is consistent with previous studies (Miyake-Stoner et al., 2009 ▸; Taskent-Sezgin et al., 2009 ▸; Bazewicz et al., 2012 ▸), where the UAA is only present at the site determined by the position of the amber codon in the protein gene. Our structures also illustrate that pCNF at site 133 is solvent-accessible and pCNF at site 149 is partially buried (Figs. 3 ▸ e and 4 ▸ b and Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 3.

sfGFP-133-pCNF refinement and structural alignment with wt-sfGFP. (a)–(c) The progression through the refinement of the sfGFP-133-pCNF structure at the 133 site is depicted from the initial structure following molecular replacement with alanine at position 133 (a), the incorporation of phenylalanine at position 133 (b) and the final refined structure with 4-cyano-l-phenylalanine at position 133 (c). The 2F o − F c density is shown as a blue mesh at 1.0σ and the F o − F c density is shown as a green mesh at +3.0σ in (a)–(c). (d, e) Alignment of the sfGFP-133-pCNF refined structure (in orange) with the wt-sfGFP structure (in green; PDB entry 2b3p) overall (d) and in the vicinity of site 133 (e). The residue at site 133 in each structure is shown in ball-and-stick representation and colored by atom type; other side-chain residues in both the sfGFP-133-pCNF and wt-sfGFP structures are shown in stick representation to illustrate the solvated nature of the site and the limited movements of amino acids in the area upon pCNF incorporation.

Figure 4.

sfGFP-149-pCNF refined structure (in cyan and magenta) with the 149 residues shown in ball-and-stick representation with atoms colored by atom type. (a, b) Structural alignment of the two sfGFP-149-pCNF molecules in the asymmetric unit (chain A in cyan and chain B in magenta) with wild-type sfGFP (in green; PDB entry 2b3p) overall (a) and at site 149 (b), where other nearby side chains from the sfGFP-149-pCNF structure are shown in stick representation and colored by atom type to illustrate the partially buried nature of the site and the limited movements of amino acids in the area upon pCNF incorporation. The chromophore is shown in gray ball-and-stick representation for reference, the residues at the 149 site are shown in ball-and-stick representation and nearby residues are shown in stick representation. (c) The 2F o − F c density around residue 149 in the refined structure is shown as a blue mesh at 1.0σ, illustrating the incorporation of pCNF at this site.

Figure 5.

Alignment of each of the six chains in the asymmetric unit of sfGFP-133/149-pCNF (in magenta) with the single chain of sfGFP-133-pCNF (in orange), the two chains in the asymmetric unit of sfGFP-149-pCNF (in cyan) and wild-type sfGFP (in green; PDB entry 2b3p). (a) The overall alignment, (b) alignment at site 133 on the solvent-accessible loop and (c) alignment at the partially buried site 149 on the side of the β-barrel. The residues at sites 133 and 149 are shown in ball-and-stick representation and colored by atom type, with the chromophore shown in gray ball-and-stick representation for reference.

Figure 6.

Alignment of each of the four chains in the asymmetric unit of sfGFP-133/149-pCCF with wild-type sfGFP (in green; PDB entry 2b3p). (a) The overall alignment, (b) alignment at the 133 site on the solvent-accessible loop and (c) alignment at the partially buried 149 site on the side of the β-barrel. The four unique chains of sfGFP-133/149-pCCF are shown in magenta, orange, blue and yellow; wt-sfGFP is shown in green and the residues at sites 133 and 149 are shown in ball-and-stick representation.

3.5. Structural effects of pCNF incorporation

The pCNF-incorporated sfGFP structures were aligned with the wt-sfGFP structure PDB entry 2b3p (Figs. 3 ▸ d, 4 ▸ a and 5 ▸ a) either using the full structure or just the residues within 10 Å of pCNF at either site 133 or 149. These two alignments permitted differentiation between global and local structural effects of pCNF incorporation. The resulting root-mean-square deviations (r.m.s.d.s) were calculated for just Cα atoms or all atoms to focus on either backbone or side-chain variations, respectively.

The r.m.s.d. values for the alignment of sfGFP-133-pCNF with wt-sfGFP either overall (0.79 Å for Cα atoms and 1.22 Å for all atoms) or within 10 Å of pCNF (0.40 Å for Cα atoms and 1.02 Å for all atoms) were relatively small. The minimal perturbations illustrate that pCNF incorporation at site 133 did not significantly alter the native protein structure globally or locally near the site. The average r.m.s.d. values for the alignment of both unique structures of sfGFP-149-pCNF in the asymmetric unit with wt-sfGFP either overall (0.75 Å for Cα atoms and 1.06 Å for all atoms) or within 10 Å of pCNF (0.15 Å for Cα atoms and 0.38 Å for all atoms) were also relatively small, again supporting that pCNF did not significantly alter the native protein structure globally or locally in the vicinity of pCNF at site 149. The slightly larger r.m.s.d.s reported in the 10 Å vicinity of pCNF incorporation for the sfGFP-133-pCNF structure compared with the sfGFP-149-pCNF structure were expected owing to the conformational flexibility of the loop region containing site 133 compared with site 149 located on the more rigid β-barrel.

The SASA calculations based upon wt-sfGFP with tyrosine modeled at sites 133 and 149 were validated by replacing pCNF with tyrosine after refinement of the sfGFP-133-pCNF and sfGFP-149-pCNF crystal structures. These calculations indicated that the SASA for sites 133 and 149 was 172 Å2 (89% solvent exposure) and 111 Å2 (58% solvent exposure), respectively, which are very similar to the previous SASA results for the wild-type structure (170 and 108 Å2, respectively).

Aligning the overall structure or residues within 10 Å of either pCNF of sfGFP-133/149-pCNF with wt-sfGFP (Figs. 5 ▸ a, 5 ▸ b and 5 ▸ c, magenta and green, respectively) produced similar results to those described for the single mutants. Specifically, the average overall r.m.s.d.s (0.80 Å for Cα atoms and 1.22 Å for all atoms) parallel the r.m.s.d.s calculated for the overall alignments of the single-mutant structures. Residues within 10 Å of site 133 on the flexible loop had greater r.m.s.d.s when compared with wt-sfGFP than residues within 10 Å of site 149 (0.45 Å for Cα atoms and 1.20 Å for all atoms and 0.29 Å for Cα atoms and 0.71 Å for all atoms, respectively), again consistent with the results that we observed in the single-mutant structures. The six molecules in the asymmetric unit of sfGFP-133/149-pCNF aligned with the structures of sfGFP-133-pCNF, sfGFP-149-pCNF and wt-sfGFP shown in Figs. 5 ▸(a), 5 ▸(b) and 5 ▸(c) illustrate some differences in the amino-acid side-chain rotamers at either site 133 or 149, but no significant backbone changes.

The two most notable structural differences between the pCNF-incorporated structures and the wt-sfGFP structure occur outside the region where pCNF is incorporated. Specifically, the loop composed of residues 188–197 appears to be in an alternate conformation in both the sfGFP-133-pCNF and sfGFP-149-pCNF structures compared with the literature wt-sfGFP structure (bottom left of Figs. 3 ▸ d and 4 ▸ a), which is distant from either the 133 or 149 sites. Additionally, the resulting electron density allowed the modeling of up to six additional amino acids at the C-terminus in the sub-2.0 Å resolution UAA-containing sfGFP constructs compared with the literature wt-sfGFP structure PDB entry 2b3p (Getahun et al., 2003 ▸; Pédelacq et al., 2005 ▸; Schultz et al., 2006 ▸; Fafarman & Boxer, 2010 ▸; Urbanek et al., 2010 ▸; Bazewicz et al., 2012 ▸).

These results illustrate that pCNF incorporation was well tolerated at both a solvated or a partially buried site located in either a loop or a β-strand region of the protein, respectively (Figs. 3 ▸ d and 4 ▸ a). It is important to note that these mutations were well accepted even though the original amino acids at sites 133 and 149 were an aspartic acid and an asparagine, respectively. The mutations discussed here are arguably less conservative than the replacement of phenylalanine or tyrosine residues with pCNF owing to the size, polarity and structure of the amino acids, further supporting the utility of pCNF to serve as an effective vibrational and fluorescent reporter UAA when placed selectively into proteins.

3.6. Structural effects of pCCF incorporation

The doubly incorporated sfGFP-133/149-pCCF structure was also assessed for structural alterations by aligning each of the four molecules in the asymmetric unit with the literature wt-sfGFP structure (PDB entry 2b3p) as described above (Fig. 6). The average r.m.s.d. values for the sfGFP-133/149-pCCF alignments either overall (0.78 Å for Cα atoms and 1.29 Å for all atoms) or within 10 Å of the 133 site (0.44 Å for Cα atoms and 1.19 Å for all atoms) or 10 Å of the 149 site (0.23 Å for Cα atoms and 0.78 Å for all atoms) of pCCF were small, illustrating that pCCF did not significantly alter the native protein structure globally or locally around pCCF. The slightly larger r.m.s.d.s 10 Å around site 133 versus site 149 are expected since site 133 is located on a less conformationally constrained secondary-structural element than site 149.

The electron density for the pCCF residue at site 133 indicated non-identical orientations for the side chain in the four unique molecules in the asymmetric unit, unlike site 149. This difference is likely to be owing to conformational flexibility of the solvent-accessible loop region at site 133 compared with the partially buried site 149 on the β-barrel. The multiple conformations observed for the pCCF at site 133 are consistent with the side chains of other native amino acids in the loop (131–135), which also take on a variety of rotamers in the four different sfGFP-133/149-pCCF molecules in the asymmetric unit (Supplementary Fig. S5).

The structure of the double-mutant sfGFP-133/149-pCCF illustrates that pCCF, in addition to pCNF, does not result in significant structural perturbations to the native protein when incorporated at either the solvent-exposed site 133 or the partially buried site 149. This result thus supports the utility of pCCF as an effective fluorescent reporter UAA of local protein structure.

4. Conclusions

The unnatural amino acids pCNF and pCCF were successfully genetically incorporated into sfGFP with high fidelity and site-specificity at a solvent-exposed site (site 133) and/or a partially buried site (site 149) in the protein. The nitrile symmetric stretch frequency of pCNF was found to be sensitive to these local protein environments. This frequency was blue-shifted by 8 cm−1 when pCNF was incorporated at site 133 compared with site 149. Crystal structures were obtained of the sfGFP-133-pCNF, sfGFP-149-pCNF, sfGFP-133/149-pCNF and sfGFP-133/149-pCCF protein constructs at 1.85, 1.42, 2.54 and 2.50 Å resolution, respectively. Comparison of each of these UAA-containing sfGFP constructs with the literature wt-sfGFP structure (PDB entry 2b3p) illustrated that the presence of the UAAs did not significantly alter the native sfGFP structure.

The crystallographic results illustrating that incorporation of pCNF and pCCF at site 133 and/or site 149 in sfGFP was well tolerated are consistent with previous crystallographic studies in which either pCNF was incorporated by semi-synthesis into ribonuclease S (Fafarman & Boxer, 2010 ▸), 4-azido-l-phenylalanine (pN3F) was genetically incorporated at site 66 in sfGFP in the internal chromophore of the protein (Reddington et al., 2013 ▸), 4-borono-l-phenylalanine (pBoF) or 4-acetyl-l-phenylalanine (pAcF) were genetically incorporated at site 66 in wt-GFP (Wang et al., 2012 ▸) or 4-pIF was genetically incorporated into T4 lysozyme (Xie et al., 2004 ▸). Each of these literature crystal structures illustrate that the incorporation of the specific UAAs did not result in significant structural perturbations to the native protein structure.

The structures of sfGFP presented here containing pCNF or pCCF help to validate the utility of these UAAs in serving as effective spectroscopic reporters of local protein environments. Each of these UAAs has readily measurable, sensitive spectroscopic observables and can be incorporated with high efficiency and fidelity into proteins with site-specificity (Miyake-Stoner et al., 2009 ▸; Bazewicz et al., 2012 ▸). However, the utility of these UAAs as effective spectroscopic reporters hinges on whether these observables are reporting on the native protein environment or an environment significantly altered by the presence of the UAA. The crystallographic results presented here illustrate that both of these UAAs are effective at measuring near-native protein environments at the sites explored in this study, since the crystal structures do not show any significant structural perturbation resulting from UAA incorporation at either site in sfGFP. Our structures containing pCNF also provide the first direct structural correlation between the UAA local environment as described by IR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. We show that pCNF at site 133 is fully solvated (Fig. 3 ▸ e) and at site 149 is partially buried (Fig. 4 ▸ b) in the crystal structure (Supplementary Fig. S2), which is consistent with the frequencies observed in the IR spectra (Fig. 2 ▸ b).

The current study does not imply that the incorporation of pCNF or pCCF will be well tolerated at all sites in all proteins; however, this study does illustrate that these UAAs are well tolerated at two unique sites in sfGFP representative of two distinct protein hydration states. These results do suggest that the selective placement of these UAAs permits local protein environments to be studied in a relatively nonperturbative fashion with site-specificity.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: sfGFP, 133 p-cyano-l-phenylalanine mutant, 5dpg

PDB reference: sfGFP, 149 p-cyano-l-phenylalanine mutant, 5dph

PDB reference: sfGFP, 133/149 p-cyano-l-phenylalanine double mutant, 5dpi

PDB reference: sfGFP, 133/149 p-ethynyl-l-phenylalanine double mutant, 5dpj

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2059798315022858/mn5104sup1.pdf

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Mertzman for obtaining materials and supplies and Kevin J. Hines for his experimental contributions. We would also like to thank Robert Grant, Marco Jost and Cathy Drennan at MIT and Amie Boal at PSU for their assistance with data collection and initial processing. This work was supported by F&M Hackman funds, F&M Eyler funds and NSF (CHE-1053946) to SHB. Data for three of the structures were collected on the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (NE-CAT) beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), which are supported by NIH NIGMS grant P41 GM103403. APS is operated for the US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory and was supported by the US DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Data for one structure were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, which is supported by the US DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the NIH NIGMS including P41 GM103393.

References

- Adam, V., Carpentier, P., Violot, S., Lelimousin, M., Darnault, C., Nienhaus, G. U. & Bourgeois, D. (2009). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 18063–18065. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221.

- Adhikary, R., Zimmermann, J., Dawson, P. E. & Romesberg, F. E. (2014). ChemPhysChem, 15, 849–853. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Aprilakis, K. N., Taskent, H. & Raleigh, D. P. (2007). Biochemistry, 46, 12308–12313. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bae, J. H., Rubini, M., Jung, G., Wiegand, G., Seifert, M. H. J., Azim, M. K., Kim, J.-S., Zumbusch, A., Holak, T. A., Moroder, L., Huber, R. & Budisa, N. (2003). J. Mol. Biol. 328, 1071–1081. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bagchi, S., Boxer, S. G. & Fayer, M. D. (2012). J. Phys. Chem. B, 116, 4034–4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bagchi, S., Fried, S. D. & Boxer, S. G. (2012). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 10373–10376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bazewicz, C. G., Lipkin, J. S., Smith, E. E., Liskov, M. T. & Brewer, S. H. (2012). J. Phys. Chem. B, 116, 10824–10831. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bazewicz, C. G., Liskov, M. T., Hines, K. J. & Brewer, S. H. (2013). J. Phys. Chem. B, 117, 8987–8993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bell, A. F., Stoner-Ma, D., Wachter, R. M. & Tonge, P. J. (2003). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 6919–6926. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chung, J. K., Thielges, M. C. & Fayer, M. D. (2011). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 3578–3583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fafarman, A. T. & Boxer, S. G. (2010). J. Phys. Chem. B, 114, 13536–13544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fraczkiewicz, R. & Braun, W. (1998). J. Comput. Chem. 19, 319–333.

- Getahun, Z., Huang, C.-Y., Wang, T., De León, B., DeGrado, W. F. & Gai, F. (2003). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Glasscock, J. M., Zhu, Y., Chowdhury, P., Tang, J. & Gai, F. (2008). Biochemistry, 47, 11070–11076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, J. M., Batjargal, S. & Petersson, E. J. (2010). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14718–14720. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hammill, J. T., Miyake-Stoner, S., Hazen, J. L., Jackson, J. C. & Mehl, R. A. (2007). Nature Protoc. 2, 2601–2607. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Henderson, J. N., Gepshtein, R., Heenan, J. R., Kallio, K., Huppert, D. & Remington, S. J. (2009). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 4176–4177. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J. C., Hammill, J. T. & Mehl, R. A. (2007). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 1160–1166. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Londergan, C. H., Baskin, R., Bischak, C. G., Hoffman, K. W., Snead, D. M. & Reynoso, C. (2015). Biochemistry, 54, 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miyake-Stoner, S. J., Miller, A. M., Hammill, J. T., Peeler, J. C., Hess, K. R., Mehl, R. A. & Brewer, S. H. (2009). Biochemistry, 48, 5953–5962. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miyake-Stoner, S. J., Refakis, C. A., Hammill, J. T., Lusic, H., Hazen, J. L., Deiters, A. & Mehl, R. A. (2010). Biochemistry, 49, 1667–1677. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, S., Taskent-Sezgin, H., Parul, D., Carrico, I., Raleigh, D. P. & Dyer, R. B. (2011). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 20335–20340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Niu, W. & Guo, J. (2013). Mol. Biosyst. 9, 2961. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.-I., Lee, J.-H., Joo, C., Han, H. & Cho, M. (2008). J. Phys. Chem. B, 112, 10352–10357. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pédelacq, J.-D., Cabantous, S., Tran, T., Terwilliger, T. C. & Waldo, G. S. (2005). Nature Biotechnol. 24, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Peran, I., Oudenhoven, T., Woys, A. M., Watson, M. D., Zhang, T. O., Carrico, I., Zanni, M. T. & Raleigh, D. P. (2014). J. Phys. Chem. B, 118, 7946–7953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Petersson, E. J., Goldberg, J. M. & Wissner, R. F. (2014). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 6827–6837. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Reddington, S. C., Driezis, S., Hartley, A. M., Watson, P. D., Rizkallah, P. J. & Jones, D. D. (2015). RSC Adv. 5, 77734–77738.

- Reddington, S. C., Rizkallah, P. J., Watson, P. D., Pearson, R., Tippmann, E. M. & Jones, D. D. (2013). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 5974–5977. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schultz, K. C., Supekova, L., Ryu, Y., Xie, J., Perera, R. & Schultz, P. G. (2006). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 13984–13985. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Smith, E. E., Linderman, B. Y., Luskin, A. C. & Brewer, S. H. (2011). J. Phys. Chem. B, 115, 2380–2385. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Storoni, L. C., McCoy, A. J. & Read, R. J. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Studier, F. W. (2005). Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Taskent-Sezgin, H., Chung, J., Banerjee, P. S., Nagarajan, S., Dyer, R. B., Carrico, I. & Raleigh, D. P. (2010). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 7473–7475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Taskent-Sezgin, H., Chung, J., Patsalo, V., Miyake-Stoner, S. J., Miller, A. M., Brewer, S. H., Mehl, R. A., Green, D. F., Raleigh, D. P. & Carrico, I. (2009). Biochemistry, 48, 9040–9046. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Thielges, M. C., Axup, J. Y., Wong, D., Lee, H. S., Chung, J. K., Schultz, P. G. & Fayer, M. D. (2011). J. Phys. Chem. B, 115, 11294–11304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tookmanian, E. M., Fenlon, E. E. & Brewer, S. H. (2015). RSC Adv. 5, 1274–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tucker, M. J., Oyola, R. & Gai, F. (2005). J. Phys. Chem. B, 109, 4788–4795. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Urbanek, D. C., Vorobyev, D. Y., Serrano, A. L., Gai, F. & Hochstrasser, R. M. (2010). J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 3311–3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Waegele, M. M., Culik, R. M. & Gai, F. (2011). J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 2598–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Waegele, M. M., Tucker, M. J. & Gai, F. (2009). Chem. Phys. Lett. 478, 249–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Walker, D. M., Wang, R. & Webb, L. J. (2014). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 20047–20060. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang, F., Niu, W., Guo, J. & Schultz, P. G. (2012). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 10132–10135. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Weeks, C. L., Polishchuk, A., Getahun, Z., DeGrado, W. F. & Spiro, T. G. (2008). J. Raman Spectrosc. 39, 1606–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xie, J. & Schultz, P. G. (2006). Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 775–782. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xie, J., Wang, L., Wu, N., Brock, A., Spraggon, G. & Schultz, P. G. (2004). Nature Biotechnol. 22, 1297–1301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ye, S., Huber, T., Vogel, R. & Sakmar, T. P. (2009). Nature Chem. Biol. 5, 397–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ye, S., Zaitseva, E., Caltabiano, G., Schertler, G. F. X., Sakmar, T. P., Deupi, X. & Vogel, R. (2010). Nature (London), 464, 1386–1389. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, J., Thielges, M. C., Seo, Y. J., Dawson, P. E. & Romesberg, F. E. (2011). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 8333–8337. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: sfGFP, 133 p-cyano-l-phenylalanine mutant, 5dpg

PDB reference: sfGFP, 149 p-cyano-l-phenylalanine mutant, 5dph

PDB reference: sfGFP, 133/149 p-cyano-l-phenylalanine double mutant, 5dpi

PDB reference: sfGFP, 133/149 p-ethynyl-l-phenylalanine double mutant, 5dpj

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2059798315022858/mn5104sup1.pdf