SUMMARY

In pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria, interactions among membrane proteins are key mediators of host cell attachment, invasion, pathogenesis, and antibiotic resistance. Membrane protein interactions are highly dependent upon local properties and environment, warranting direct measurements on native protein complex structures as they exist in cells. Here we apply in vivo chemical cross-linking mass spectrometry, to reveal the first large-scale protein interaction network in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic human pathogen, by covalently linking interacting protein partners, thereby fixing protein complexes in vivo. A total of 626 cross-linked peptide pairs, including previously unknown interactions of many membrane proteins are reported. These pairs not only define the existence of these interactions in cells, but also provide linkage constraints for complex structure predictions. Structures of three membrane proteins, namely, SecD-SecF, OprF, and OprI are predicted using in vivo cross-linked sites. These findings improve understanding of membrane protein interactions and structures in cells.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) is a Gram-negative, opportunistic pathogen that causes serious and re-occurring infections in immunocompromised individuals, including cystic fibrosis patients (Rosenstein and Zeitlin, 1998). The intrinsic virulence of PA, the emergence of multi-drug resistance (MDR) strains, and the treatment-resistant phenotype of chronic PA infections (Oliver et al., 2000), underscore the need for the development of novel therapeutic options. Since nearly all biological functions in living cells are regulated by protein-protein interactions (PPIs), improved understanding of PPIs could yield new avenues for effective therapies. However, despite the significance that large-scale interaction data could hold in drug development, the current knowledge on PA PPIs is limited to only a few manually curated interactions (Goll et al., 2008) discovered using small scale targeted experiments (Goure et al., 2004; Marquordt et al., 2003; Robert et al., 2005).

Recently, genome-scale prediction of PPIs in PA integrated various genomic features of PA genes and their protein products, such as essentiality, co-expression, co-localization, domain-domain interaction, co-operon or co-gene cluster information etc. against a compiled reference dataset created from known PPIs in three closely related Gram-negative bacteria (Zhang et al., 2012). Such databases provide a key first step in defining relevant PPIs in bacterial pathogenicity and drug resistance, and can be greatly accelerated by experimental measurements. Furthermore, empirical measurements can reveal what interactions are actually present and can advance predictions, since two proteins that do not share a common operon and are thought to be present in different subcellular locations could, in reality co-localize and interact in vivo, and thus, would not be predicted with high confidence to be interactors.

Mapping PPIs experimentally can be achieved by employing well established methods such as the high-throughput yeast two-hybrid method of genome-level screening (Fields and Song, 1989),Tandem affinity purification (Puig et al., 2001), and co-immunoprecipitation (Bauer and Kuster, 2003). However many of these techniques require protein isolation or assay under non-native conditions that can increase both false positive and false negative results. Chemical cross-linking with mass spectrometry (XL-MS) has emerged as a powerful tool for mapping PPIs from protein complexes (Herzog et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2010; Sinz, 2003; Tang et al., 2005) and provides highly complementary information to conventional methods with several unique advantages. These include the ability to identify PPI networks that exist in vivo, formed by proteins which are in close proximity due to a direct interaction or due to their interactions with a third protein (Guerrero et al., 2006; Vasilescu et al., 2004). XL-MS data can also be utilized to provide structural information of functional protein complexes. For example, chemical cross-linking of intact infectious virus particles of the Potato Leafroll Virus revealed interactions sites among viral coat proteins that enabled prediction of interfacial surfaces based on cross-link site-directed docking (Chavez et al., 2012).

A third notable advantage of in vivo XL-MS is its ability to identify PPIs and structural features directly from intact cells (Zhang et al., 2008), including those of membrane proteins. Membrane proteins represent nearly 30% of the entire eukaryotic proteome (Wallin and von Heijne, 1998), include desirable drug targets (Yildirim et al., 2007) and yet, they are under-represented in the protein data bank with a only few hundred known crystal structures. Crystallization of intact membrane proteins is extremely challenging as these species are often structurally unstable once removed from their native environment. In vivo chemical cross-linking circumvents these technically challenging steps by linking membrane proteins in their native forms, capturing their complexes and interactions as they exist in cells (Chavez et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2008). Due to these advantages, XL-MS has been applied to study protein complexes from variety of samples including intact bacteria (Weisbrod et al., 2013a), virus particles (Chavez et al., 2012), mammalian cells (Vasilescu et al., 2004), and cell lysate (Rinner et al., 2008).

Given the value of protein interaction networks in identifying novel drug targets for human opportunistic bacteria (Cui et al., 2009), we focus on large-scale mapping of PPIs network in living PA cells using XL-MS. These efforts revealed several previously unknown interactions of structural outer membrane lipoproteins with periplasmic, cytoplasmic and hypothetical proteins. The occurrence of such PPIs between proteins of different annotated subcellular locations highlights the dynamic nature of protein localizations. Protein functions are related to their network topology; hence, interactions detected between hypothetical proteins and lipoproteins provide insight on possible functional involvement of these hypothetical proteins. Furthermore, the experimentally observed peptide-peptide cross-links found within a protein and between two proteins allow prediction and visualization of structural features of proteins and complexes for which no structural or functional information is available. Therefore, results derived from proteome-wide cross-linking experiments not only extend the current understanding of the protein interaction network in PA but also provide the first in vivo topological details on these interactions using an unbiased approach. This comprehensive protein interaction network can serve as a valuable resource to the community that can utilize the cross-link site information from the present dataset to derive structural information for proteins of interest.

RESULTS

PA cells were cross-linked by a Protein Interaction Reporter (PIR) cross-linker called BDP-NHP (nhydroxyphthalamide ester of Biotin Aspartate Proline) and the cross-linked digest was analyzed using Real-time Analysis for Cross-linking Technology (ReACT), an in-house mass spectrometric-based method (Weisbrod et al., 2013a) (Suppl. Fig. S1a; Suppl. Experimental Procedures). A sample-specific Stage 1 database comprised of 9122 unique peptides identified with ≤ 1% false discovery rate (FDR) corresponding to 1282 unique proteins (≥ 2 peptides/protein) (Suppl. Table S1) was created and ReACT MS data was searched against the Stage 1 database to identify cross-linked peptides. At this step, a higher FDR threshold of 5% was employed to filter the identified peptide matches since an additional requirement of peptide mass modification (BDP stump mass) was also employed to ensure confidence in the cross-linked peptide matches. It should be noted that in a given cross-linked peptide pair, either one or both the peptides may contain decoy sequences (target-decoy/decoy-decoy) instead of being assigned to target sequences (target-target). A global FDR of 3% was calculated to determine the percentage of cross-linked pairs containing one or both decoy sequences (target-decoy and decoy-decoy) rather than target sequences (target-target), as an estimate of the FDR of cross-linked peptide pair identification. The advantage of using a sample-specific Stage 1 database containing target and decoy protein sequences for confident identification of cross-linked peptide pairs with reduced FDR has been demonstrated previously (Anderson et al., 2007; Chavez et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2009). Representative proteins from all subcellular compartments were found cross-linked and their respective percentages in the Stage 1 database (Suppl. Fig. S1b) were directly proportional to their constitutive numbers in the entire PAO1 database, indicating that under the given cross-linking reaction conditions, the BDP-NHP cross-linker is not biased towards proteins of a particular cellular compartment. Identification of the cross-linked peptide pairs of cytoplasmic proteins indicate PIR molecules penetrate into PA cells, as has been demonstrated previously with mass spectrometry and immuno-nanogold electron microscopy imaging of other PIR cross-linked bacterial cells (Tang et al., 2007) and with confocal microscopy of PIR labeled human cells (Chavez et al., 2013).

After implementing the above data processing steps, we identified a total of 690 unique cross-linked peptides forming a total of 626 peptide pairs (Suppl. Table S2) from a total of 211 proteins. All cross-linked peptide pairs identified in this work are presented in our on-line cross-linked peptide database XLink-DB (http://brucelab.gs.washington.edu/xlinkdb/specViewerPA.php). Of these, 437 (70%) were between peptides of a single protein with non-identical and non-overlapping sequences, and are referred here as ‘intra-cross-link pairs’, 53 (8%) corresponded to links between two peptides of a single protein with overlapping and identical sequences, and are termed as ‘unambiguous homodimer links.’ The remaining 136 (22%) cross-linked peptide pairs were between peptides of two different proteins and are referred as ‘Inter-cross-link pairs’. It is worth mentioning that ReACT allows identification of hetero- and homodimer peptide pairs with equal probability. Several methods have been published to enable identification of non-cleavable cross-linked peptides (Rinner et al., 2008; Trnka et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2012). While it is conceivable that several of these strategies could show enhanced identification of homodimer peptide pairs since both peptides share common fragments in the complex MS2 spectra, this is not the case with cleavable cross-linkers (Tang et al., 2005) and ReACT (Weisbrod et al., 2013a), and other similar methods (Kaake et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2012). ReACT calculates masses of the released cross-linked peptides as they are cleaved from the cross-linker and then fragments both the peptides separately for peptide identification. This is true for both, homo- and heterodimeric peptide pairs, allowing identification of both types of cross-linked peptide pairs without a bias towards homodimeric links.

PIR XL-MS identify binary protein interactions because two linked peptides are used to establish connectivity. Thus, it is currently not straight-forward to ascertain if cross-linking sites among several proteins indicate the presence of multi-protein complexes or simply several binary interactions. For intra-protein cross-links between peptides with non-identical or non-overlapping sequences, additional efforts are often required to determine if the two linked peptides belong to one protein monomer or two monomers of the same protein. In contrast, when both the cross-linked peptides share the same or overlapping amino acid sequences (homodimer link) and if the peptide sequence occurs just once within a protein, this unambiguously indicates the existence of a multimeric complex between two or more identical monomers of a protein (Anderson et al., 2007). We used the intra-cross-links, the unambiguous homodimers, and inter-protein cross-linked sites to build monomeric protein models and to filter homo- and hetero-dimeric protein models.

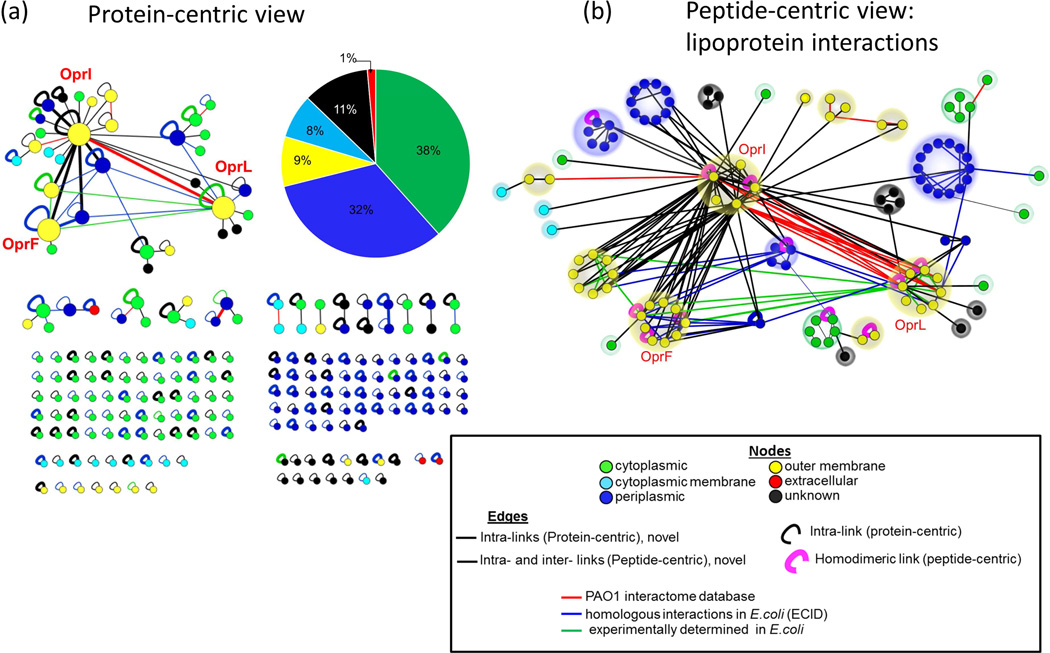

All 260 protein-level PPIs (Suppl. Table S3) are depicted in Fig. 1a in a protein-centric view, while a peptide-centric network of the highly cross-linked major lipoproteins is shown in 1b. Each cross-linked protein (1a) or peptide (1b) is denoted as a node. In a peptide-centric view (1b), when more than one peptide of a protein is cross-linked, the corresponding peptide nodes are arranged in a circular cluster. Different edge colors indicate that the identified PPI is included in a computationally predicted PAO1 interactome database (edge color: Red) and/or is a homologous PPI in E.coli, previously reported in the EcID database (edge color: Blue) and/or is identified from PIR cross-linked E.coli cells in our lab (edge color: Green; (Weisbrod et al., 2013a; Zheng et al., 2011, and additional efforts http://brucelab.gs.washington.edu/xlinkdb/dataRetriever.php?tablename=ecoli_total&dataset=&privateFlag=1), or is a previously unknown PPI (edge color: Black). An experimentally validated protein interaction database for PA does not currently exist; however, the cross-linking-derived binary protein interaction network was compared to a predicted PAO1 interactome database (Zhang et al., 2012)(Red edges). Only 7 PPIs between the cross-linked proteins that share an operon (SecD-SecF; SucC-SucD; LptE-LptF) or a subcellular location (i.e., membrane proteins: OprI-OprL, OprI-OprN or cytoplasmic proteins: SucA-rpsG and rplB-fusA) were found in the predicted PAO1 interactome database. Empirical in vivo measurements of predicted interactions is important and can further advance predictions since two proteins that are not co-expressed or are thought to be present in different cellular compartments could, in reality co-localize and interact in vivo, and thus would not be predicted as high confidence interactors. A majority of PPIs identified between PAO1 proteins were either reported for homologous E.coli proteins in the EcID database (Suppl. Table S4) or were identified from the PIR cross-linked E.coli cells suggesting that these interactions are conserved among the two Gram-negative bacteria.

Figure 1.

PIR cross-linked derived large-scale PPI profile obtained from intact PA cells (1a) and a peptide-centric view of the major lipoprotein interactions (1b). Nodes in 1a represent proteins and connections denote cross-link-interactions. In the peptide-centric view of the lipoprotein interactions (1b), multiple (≥2) cross-linked peptides of a single protein are arranged in a circle layout. Edge colors in 1a and 1b represent computationally predicted PA protein interactions from PAO1 interactome database (red), homologous PPI in E.coli as reported on the EcID database (Blue), homologous PPI from cross-linked E.coli cells (green), and novel interactions (Black). Intra-links in 1a are shown as semicircular edges and the homodimeric links in 1b are indicated by colored semicircular (magenta) edges. Node colors from 1a and 1b denote protein subcellular locations. The PPI network layout was directed by connectivity of the nodes in Cytoscape program and the three highly connected membrane proteins, namely OprI, OprL and OprF are highlighted by bigger node size. A pie chart from panel 1a shows the distribution of the subcellular locations of all the 211 identified cross-linked proteins.

Outer membrane lipoprotein OprI, peptidoglycan (PG)-associated lipoprotein, OprL, and major porin, OprF, were among the highly connected proteins (larger nodes, Fig. 1a), forming interactions with 22, 9 and 6 other PAO1 proteins, respectively. It is important to note that cross-linked outer membrane proteins contributed only a small proportion (9%) of the total detected cross-linked proteome, while the majority of cross-linked proteins were from soluble cytoplasmic (38%) and periplasmic (32%) regions (Fig. 1a, pie chart). This suggests that while the PIR cross-linker molecules permeated through the cell membrane barrier into the inner cell compartments, the higher number of intra- and inter-cross-links detected for major lipoproteins is likely due to their high abundance in the cell envelope (Mizuno and Kageyama, 1979b). This compartment is first to come in contact with the incoming cross-linker so that during the short half-life of the PIR cross-linker in the time scale of tens of minutes, outer membrane proteins are likely to be readily cross-linked, provided that reactive lysine (Lys) sites within the protein sequence are accessible. The limitation of MS-based approaches for detecting low abundant species from complex biological systems is shared by in vivo cross-linking technology. As technologies improve with greater MS speeds, improved bioinformatics capabilities, and sample preparation workflow, wider dynamic range of detection is achieved. It is also important to note that the cross-linking data enabled structural predictions of these abundant proteins and their complexes, for which no crystal structures are currently available. Most conventional methods of protein structure determination require highly purified, isolated proteins and often fail even with highly abundant membrane proteins. In vivo cross-linking obviates the need to perturb native proteins to gain structural information and is complementary to other conventional structural methods.

A peptide-centric view of the lipoprotein network shows the number of unique cross-linked peptides of the lipoproteins and their interacting partners (Fig. 1b). All three lipoproteins contain multiple residues that are accessible for forming intra-links (OprI: 21 intra-links; OprF: 9 intra-links, and OprL: 12 intra-links), and homodimeric-intra-links (Fig. 1b, Suppl. Table S2). The existence of unambiguous homodimeric-links between peptides with identical sequence confirms that the three lipoproteins form homo-dimeric complexes in vivo. The same sites of intra-cross-links were also involved in inter-protein cross-links with other PA proteins. These identified interactions involve proteins functionally linked to membrane processes such as secretion, transport and several metabolic processes and structural details of these interactions are lacking. Interestingly, all the cross-linked sites of these PPIs were located near the carboxy termini of OprI, OprF and OprL (Fig. 2), suggesting that the C-termini of these key membrane proteins are exposed, and are more likely to participate in PPIs as compared to their membrane-bound (Khalid et al., 2006) or lipidated N-termini (Mizuno and Kageyama, 1979b). A domain-domain interaction profile of all the cross-linked PAO1 proteins obtained from a Structural Classification of Proteins database (SCOP database, 1.75v) (Andreeva et al., 2008) revealed that the highly cross-linked carboxy termini of two of the major lipoproteins, OprF and OprL share a common ‘OmpA-like domain’ (Fig. 2). In the case of OprI, all the associated PPIs were mapped to an unannotated domain due to the lack of a known structural or functional domain for this protein. This C-terminal unannotated region of OprI interacted with the highly conserved OmpA-like domains of five other membrane proteins, namely, lipotoxin (lptF), a probable membrane protein (Q9I4T3) and the two lipoproteins OprF and OprL.

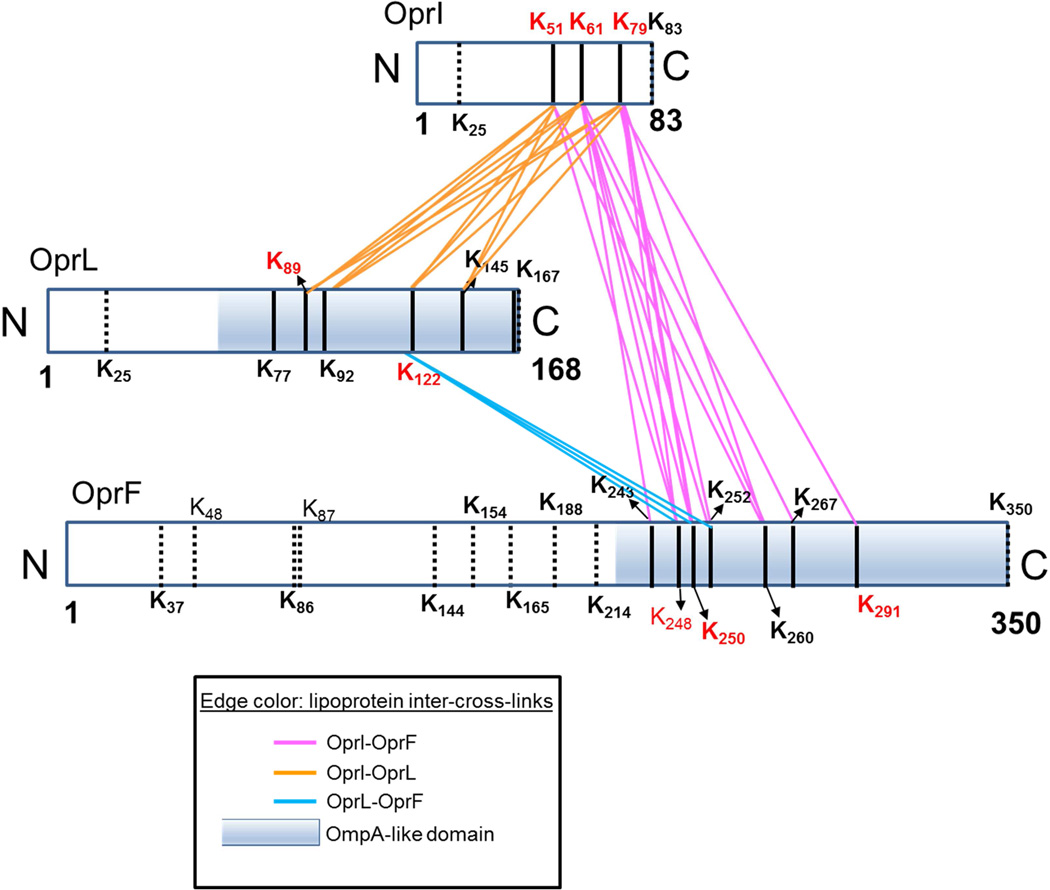

Figure 2.

A block diagram shows relative protein lengths of OprI, OprF and OprL with black lines denoting the positions of all Lys residues within the mature form of lipoprotein sequences. Dotted and solid black lines mark the positions of un-cross-linked and cross-linked Lys. Homodimeric sites are marked in red. Pink, orange and light blue lines denote inter-cross-linking between OprI-OprF, OprI-OprL and OprF-OprL, respectively. The OmpA-like region in OprL and OprF is shown as shaded blue box. See S2.

The mature form of OprL has 8 Lys residues, 7 of which are located in the OmpA-like domain that spans from 56–168 amino acid residues. Of the 7 Lys residues from the OmpA-like domain, 6 were found inter- or intra-crosslinked, while the 7th Lys at the protein C-terminus was not identified in any cross-linked relationship in the present study. When the protein sequences of OprL and its homolog PAL from E. coli were aligned, the OmpA-like domains of the two lipoproteins showed 40% sequence alignment (Suppl. Fig. S2a). In PAL, the OmpA-like region contains PG-binding sites, PAL dimerization sites, and sites of known interactors of PAL, namely TolA, TolB and OmpA (OprF homolog) as indicated in Suppl. Fig. S2 (Cascales and Lloubes, 2004). Interestingly, two OprL Lys residues, K89 and K122 involved in forming inter-links with the OmpA homolog OprF aligned with N93 and N127 of E. coli PAL and differ by single base substitutions at this codon. Furthermore, although these sites (N93 and N127) appear somewhat distant in sequence from the OmpA binding region in PAL, both flank the β-strand and loop region on the PAL C-terminal crystal structure that were shown by site-directed mutagenesis (Cascales and Lloubes, 2004) to be important for OmpA interaction (Suppl. Fig. S2b). The same Lys residues (K89 and K122 in OprL) were identified as the sites of unambiguous homodimeric links, confirming the existence of in vivo dimerization of OprL, as also shown previously for E. coli PAL (Cascales and Lloubes, 2004). The non-cross-linked Lys residue from the OprL N-terminus aligned within the unstructured membrane-bound N-terminal of PAL (dotted line, Suppl. Fig. S2a) (Abergel et al., 2001) that was suggested to be a functionally silent (Cascales and Lloubes, 2004) flexible tail, only serving to anchor the protein into the outer membrane (Abergel et al., 2001). Therefore, the highly cross-linked C-terminal domain of OprL containing the OmpA-like region must also be functionally important, and accessible to other PA proteins within the periplasmic region.

Similar to OprL, all of the cross-linked Lys residues of OprF are located near C-terminal region, in the OmpA-like domain (Fig. 2). The PG-associated major porin protein OprF has been studied extensively, first due to its proposed multifunctional roles, as a nonspecific porin (Woodruff and Hancock, 1988), and its involvement in cell wall structural stability (Rawling et al., 1998), yet controversy still exists surrounding the structure. Early studies involving surface epitope mapping (Rawling et al., 1995) predicted a one-domain secondary structure for OprF with 15 transmembrane strands traversing the entire protein length (Suppl. Fig. S2c–i). A later report (Sugawara et al., 2006) suggested that OprF may exist in two forms; a highly abundant ‘two-domain form’ containing membrane-bound N-terminal β-barrel with a periplasmic globular C-terminal domain and a low abundance ‘one-domain form’ similar to that mentioned above which contains only a β-barrel structure spanning the entire length of the protein (Suppl. Fig. S2c–ii). Since all cross-link sites of OprF are located near the C-terminal region, the cross-linking results identified here are most consistent with the abundant two-domain conformer of OprF where the solvent accessible C-terminal domain resides in the periplasmic space. Secondly, the cross-linked Lys residues of OprF were also identified in inter-protein links with Lys residues of PAL and OprI within domains of these proteins that are also located in the periplasmic region. This further suggests that these C-terminal cross-linked regions of all three outer membrane proteins exist close to one another (within 35 Å) within the solvent accessible periplasmic space. Third, OprF formed homodimeric intra-links (Fig. 1b) in the C-terminal region similar to its E. coli homolog OmpA where previous in vivo cross-linking data enabled OmpA C-terminal dimer structure prediction (Zheng et al., 2011). Subsequent site-directed mutagenesis experiments (Marcoux et al., 2014) confirmed that the dimerization interface of OmpA is present in the soluble periplasmic C-terminus.

DISCUSSION

Membrane protein interactions of OprI

Unique insight that can be gained from the present in vivo cross-linking data relates to the intricate network of membrane proteins, such as the outer membrane lipoproteins OprI, OprF and OprL (Fig. 1). PA outer membrane protein OprI was first isolated and characterized as a homolog of the free-form of E. coli lipoprotein LPP by Mizuno and co-workers (Mizuno and Kageyama, 1979b). The same group also confirmed the association of OprF and OprL with the PG layer (Mizuno and Kageyama, 1979a). OprI was suggested to be present largely as an unbound form in PA strain PAO1 and the existence of the PG-bound form can vary among strains of the bacteria (Mizuno and Kageyama, 1979a). In the present study, OprI was identified as the highest connected protein, linked to 17 other proteins, including OprF and OprL (Suppl. Table S2), in addition to the homodimeric intra-links (Table 1, Fig. 1b, and 2). Interestingly, all these interactions of OprI were near the C-terminus at Lys residues 51, 61 and 79 (Fig. 2), suggesting that this region of OprI must reside in the solvent accessible periplasmic space, and is likely to contain functionally-important residues.

Table 1.

A list of the homodimeric intra-cross-link peptide pairs of protein OprI. Unique peptide pairs showing the site of PIR-crosslinking (underlined) is listed, along with the residue number of the cross-linked Lys from each peptide. Numbering of cross-linked lysine residues within a protein sequence follows the Uniprot sequence annotation, starting with Methionine as the first amino acid residue. Post-transnationally modified (oxidation) Methionine residues in the cross-linked peptides are highlighted in bold.

| Peptide 1 | Peptide 2 | Protein Uniport ID |

Gene name |

Cross- linked lysine site1 |

Cross- linked lysine site2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLEKASRK | MLEKASR | P11221 | oprI | 79 | 79 |

| MLEKASR | MLEKASRK | 79 | 79 | ||

| KADEALGAAQKAQQTADEANER | KADEALGAAQK | 51 | 51 | ||

| KADEALGAAQKAQQTADEANER | ADEALGAAQKAQQTADEANER | 61 | 61 | ||

| MLEKASR | MLEKASR | 79 | 79 | ||

| MLEKASR | MLEKASR | 79 | 79 | ||

| MLEKASR | MLEKASR | 79 | 79 | ||

| KADEALGAAQKAQQTADEANER | KADEALGAAQKAQQTADEANER | 61 | 61 |

OprI-OprF-OprL interaction

Potential role in cell envelope structure stability Our in vivo cross-linking efforts resulted in identification of several inter-protein interactions between the C-terminal of OprI and C-terminal OmpA-like domains of OprF and OprL, involving 13 and 11 inter-cross-link peptide pairs, respectively (Fig. 2). In addition, OprL and OprF C-terminal inter-protein linkages were identified, suggesting the existence of an intracellular ternary lipoprotein complex in cells, consistent with that in E. coli (Cascales et al., 2002). The sequence homologs of OprI, OprF and OprL in E. coli, namely, LPP, OmpA and Pal were shown to form multi-protein complexes during in vivo cross-linking and immunoprecipitation experiments and it was suggested that interaction between PAL and OmpA provides cell membrane integrity in E. coli (Cascales et al., 2002). The presence of conserved PPIs between the homologous lipoproteins within E. coli and PA support similar functional roles of their interactions across the two closely related Gram-negative bacteria. Additionally, OprF was proposed to be important for structural integrity (Rawling et al., 1998) where the possible association of the two-domain OprF conformer discussed above with OprL and OprI was suggested to be relevant for cell shape and outer membrane stability in PA. The observed inter-links between OprF and the two lipoproteins confirm the existence of these associations in vivo.

OprI interactions with bacterial lipotoxins

Inter-protein links between OprI and two of the PA lipotoxins, namely, LptF and LptE were identified, and a single inter-link was also detected between the two lipotoxins (Suppl. Table S2, Suppl. Fig. S2d–i). LptF and LptE are the two outer membrane lipoproteins, with multifunctional roles as pro-inflammatory factors (Firoved et al., 2004), and in the survival of PA under harsher environments (Damron et al., 2009) that share an operon (Database) and were detected in the outer membrane vesicle (OMV) proteome of the bacteria (Choi et al., 2011). Based on their common operon, LptF and LptE (Suppl. Fig. S2d–ii) were predicted to interact (Zhang et al., 2012). Our unbiased in vivo cross-linking data provide the first direct evidence of their interaction in living bacterial cells, along with interaction with major lipoprotein OprI. The positions of the inter-protein cross-linked sites between the two lipotoxins and OprI suggest that the C-terminal region of LptE and the OmpA-like domain of LptF are in proximity of OprI periplasmic domain. The association between LptF and LptE proteins with OprI and their presence in OMVs raise the possibility that these interactions may be important for extracellular trafficking of these multifunctional lipoproteins via OMVs.

Interaction of Transmembrane proteins SecD-SecF: Prediction of a functional protein complex

The Sec protein machinery is a well conserved secretion system in Gram-negative bacteria that enables export of newly synthesized membrane proteins and other secreted proteins across the inner membrane to their final destination. Two components of the Sec apparatus SecD and SecF, each contain six transmembrane helices and are known to form a complex and interact with the SecYEG translocon to facilitate protein transport from cytoplasmic to periplasmic space via proton motif force (Arkowitz and Wickner, 1994). The large periplasmic loop of SecD appears important to maintain proper function of the SecDF protein complex (Nouwen et al., 2005). Although reports of successful co-crystallization of SecD and SecF have not yet appeared, the crystal structure of a fused form of SecD and SecF (TsecDF) from Thermus thermophilius has been published (Tsukazaki et al., 2011) (Fig. 3a). TsecDF can assume two forms, a substrate capturing F-form and substrate releasing I-form (Tsukazaki et al., 2011). The periplasmic head region (P1) of SecD domain of TsecDF moves towards (I-form) or away from (F-form) the periplasmic side (P4) of SecF domain, aided by a small ‘hinge’ region in the base of P1, and as a result, a substrate protein is captured from the translocon and subsequently released into the periplasm (Tsukazaki et al., 2011). Critical residues identified in TsecDF include Leu106 and Leu243 that are required for proton motion and flexibility of the hinge region (Tsukazaki et al., 2011).

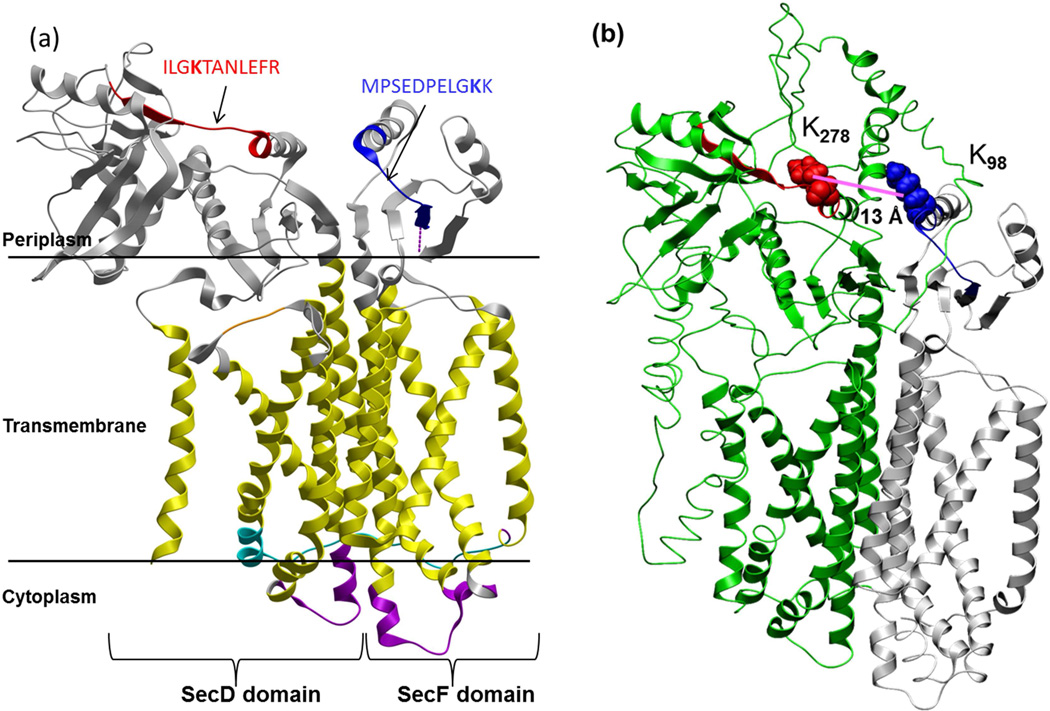

Figure 3.

(a) Crystal structure of the fused SecD-SecF protein (TsecDF) from Thermus thermophilius, showing the SecD and SecF domains containing six transmembrane domains (yellow) each, and periplasmic (grey) and cytoplasmic (purple) domains. Location of the cross-linked peptides from PAO1 SecD (Red) and SecF (blue) was mapped onto the crystal structure. Also see S5. (b) The top scoring predicted structure of concatenated PA SecD-secF using I-TASSER. The green and grey portions denote the SecD and SecF portions of the concatenated complex. See S3.

The PIR XL-MS dataset contain one cross-linked peptide pair of PAO1 SecD (ILGKTANLEFR) and SecF (MPSEDPELGKK), along with one intra-link peptide pair within protein SecD (Suppl. Fig. S1c). When the sequences of SecD and SecF were aligned with TsecDF, position of these peptides were aligned with TsecDF (>40 % sequence similarity, Suppl. Fig. S3a) and visualized on the TsecDF crystal structure, the cross-linked peptide from PAO1 SecD (ILGKTANLEFR) was situated on the functionally important flexible linker or ‘hinge’ portion of the TsecD domain while the SecF peptide (MPSEDPELGKK) aligned with the loop region of the TsecDF domain (Figure 3a). Since loop regions are often involved in protein-protein recognition (Planas-Iglesias et al., 2013), it is possible that these loop regions of SecD and SecF are crucial for functional complex formation. Sequence alignment efforts also revealed that critical residue Leu106 in the TsecDF hinge region is aligned to Ile of the cross-linked peptide ‘ILGKTANLEFR’ from SecD. Furthermore, the second Leu243 critical for proton transport is conserved in SecD along with other transmembrane amino acid residues of TsecDF (Suppl. Fig. S3a).

Due to the sequence similarities shared by SecD and SecF proteins with the fused TsecDF form, the protein sequences of PAO1 Sec proteins were concatenated to form a fused version and structural model prediction was performed with I-TASSER (Roy et al., 2010). The five predicted structures (Suppl. Fig. S3b) closely resembled the TsecDF structure and on the top model (TM-score of 0.53± 0.15) as shown in Figure 3b ((http://www.modelarchive.org/) DOI: ma-a4bdy), the observed cross-linked sites were positioned approximately 13 Å apart (Cα- Cα atoms of cross-linked Lys), in excellent agreement with previous PIR cross-linked site distributions (Chavez et al., 2013). These results illustrate that cross-linking data can identify locations of protein interaction interfaces and can shed light on relevant structural features of complexes that have not yet been successfully studied with crystallography.

Homodimer interactions of membrane lipoproteins

Protein dimerization/ oligomerization is ubiquitous in biology (Marianayagam et al., 2004). Dimerization of membrane proteins can facilitate ion channel formation (Zheng et al., 2011), signal transduction (Yu et al., 2002), and can provide structural stability. Cross-linked products that include two linked identical or overlapping peptide sequences can yield unambiguous identification of homomultimeric interactions. Direct in vivo cross-linking measurements of the lipoprotein complexes revealed several unambiguous homodimer linkages as described below, and can help extend the current knowledge about their structures and possible functions as they exist in the cellular environment.

Homodimeric links of Major outer membrane lipoprotein (OprI)

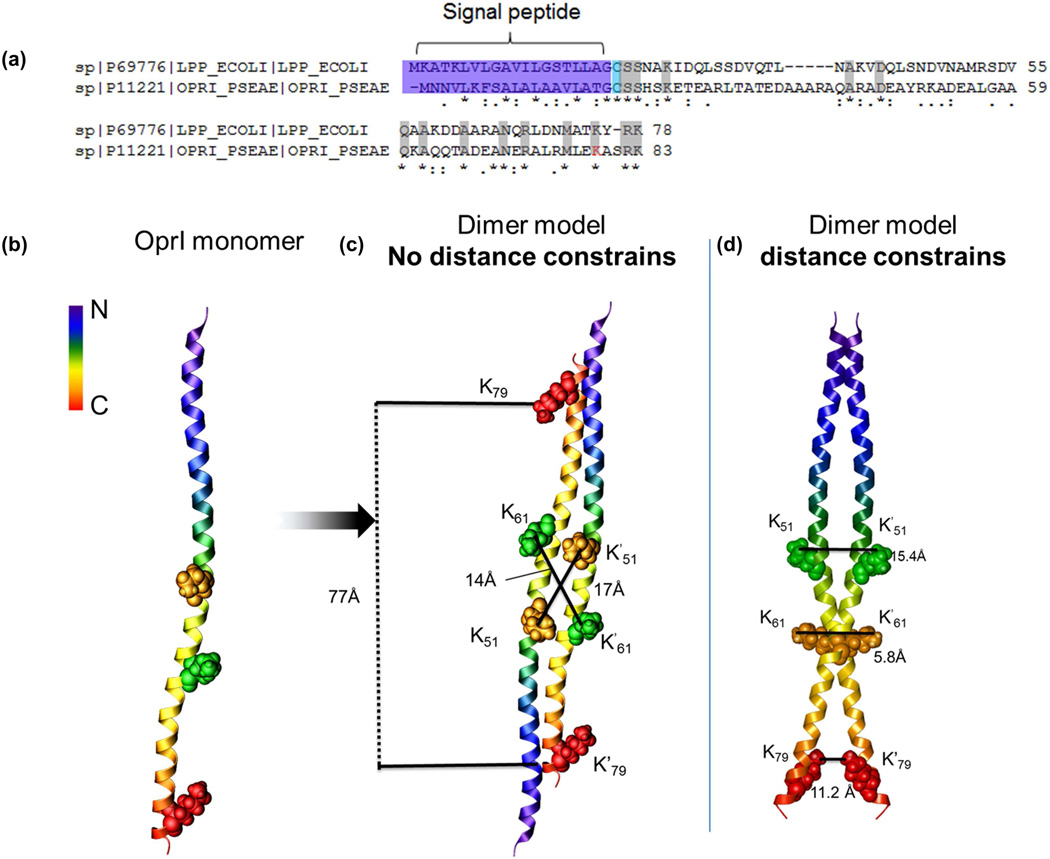

Unambiguous homodimer links of OprI involving three cross-linked sites were identified (Table 1) and the same sites were also identified in inter-linked relationships. Oligomeric forms of native OprI were detected by Western Blot in a study by Lin et al. (Lin et al., 2010) and its homolog protein LPP from E. coli is known to exist as a homotrimer (Shu et al., 2000). LPP and OprI show similar properties such as their molecular weights, unique solubility in 10% trichloroacetic acid/SDS, composition of fatty acids, and both proteins are rich in α-helix (Mizuno and Kageyama, 1979b). Lpp and OprI share 25% sequence similarities, including the N-terminal lipidated cysteine, carboxyl-terminal Lys which can be free or covalently bound to the PG layer, as shown in the sequence alignment of the proteins (Figure 4a). One Lys of LPP (Lys75), corresponding to Lys79 of OprI (highlighted in red) was also found cross-linked in a homodimeric intra-link (unpublished results). Due to the similarity of the two proteins, the crystal structure of LPP-56 mutant was used to predict the monomeric model of OprI using homology modeling software I-TASSER (Roy et al., 2010) (Fig. 4b). Of the four predicted models, only a single model had a high confidence (C)-score of 0.33 (C-score range:-5 to 2), while each of the remaining three models had a C-score of -5, signifying lower quality models (Suppl. Fig. S4a). The top model (TM-score 0.76 ± 0.10) of OprI was then used with SymmDock to generate a dimer of OprI (Fig. 4c–d). A cross-linking distance constraint of 35 Å was used as an additional criterion to filter the resulting dimeric models. As can be seen from Fig. 4c–d, when no distance constraint information was used to generate the dimer structure, the resulting top 20 models showed an antiparallel orientation of the two monomers (Fig.4c) with a 75 Å distance between one of the cross-linked Lys residues (K79) of the two monomers. Since N-terminal Cysteine residue in LPP is lipid modified and serves as an anchor in the outer membrane to increase cell integrity, this dimeric complex with antiparallel orientation would appears less favorable due to the fewer lipoprotein insertion sites in the outer membrane. On the contrary, the top twenty dimer models of OprI (Suppl. Fig. S4b) generated with the cross-linking distance constraints showed parallel orientation of the OprI monomers, with their N- and C-termini oriented in the same direction as shown in the case of the top most representative model in Fig. 4d (The Model Archive DOI: ma-a89gj), and all the linear and nonlinear distances (Suppl. Table S5) measured between the cross-linked Lys residues of the monomers were well within the maximum distance expected for the PIR cross-linker (Chavez et al., 2013).

Figure 4.

(a) Sequence alignment of OprI and its E. coli homolog LPP showed 25% sequence alignment. Conserved aa residues (grey), lipid-bound cysteines (cyan), the signal peptide sequence at the N-terminal (purple) are highlighted. Lys79 from OprI found inter- and intra-cross-link is highlighted in red. (b) OprI monomer structure was predicted using I-TASSER, using LPP-56 mutant protein as a template. The cross-linked Lys molecules are shown on the ribbon structure of OprI. Two monomers of OprI were docked onto each other using SymmDock to generate a dimer, with(c) and without (d) using the cross-linking site distance constrain information. The resulting dimer models were evaluated for the distance between the cross-linked Lys. See S4 a–b.

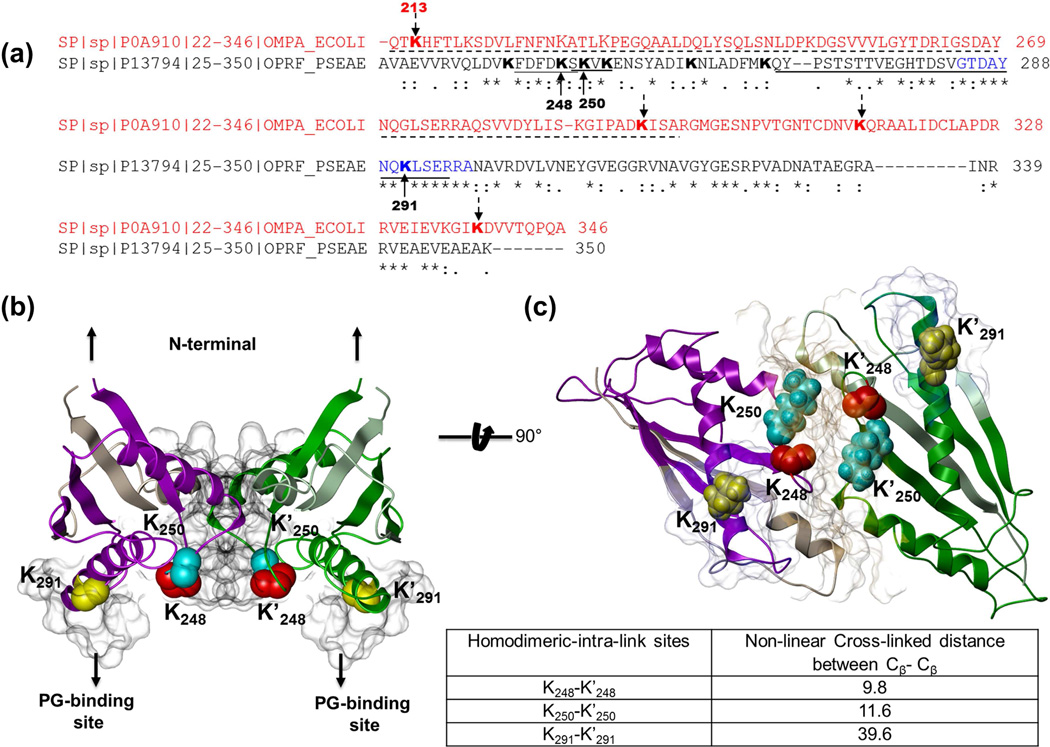

Homodimeric links of Major porin (OprF)

XL-MS analysis identified two unambiguous homodimeric links of OprF, one at K291 and another at K248 (Table 2). An additional homodimer link was observed at K250 with both cross-linked peptides observed with the sequence SKVK, although this short sequence could have originated in several PA proteins. On the other hand, the peptide SKVK was also identified cross-linked to FDFDKFK which would be expected given the proximity of these two lysine residues in OprF, as well as three other peptides unique to OprF. (Fig. 5a) Thus it is likely that ‘SKVK’ indeed belongs to the major porin, although it was not used for cross-link site-directed docking below. The adjacent position of the homodimeric cross-link sites 248 and 250 suggest that the periplasmic region of OprF plays a role in the formation of dimeric or homomultimeric complexes, similar to that of its homolog in E. coli, OmpA. The interaction among OmpA C-terminal domains was first demonstrated with in vivo cross-linking and a model structure of the OmpA C-terminal dimer was proposed based on cross-link site-directed docking (Zheng et al., 2011). Recent in vitro studies confirmed OmpA dimer existence and demonstrated the requirement of the OmpA C-terminal domain for dimer formation (Marcoux et al., 2014). Sequence alignment of OmpA and OprF C-termini showed that the homodimeric cross-linked region in OprF aligns with the dimerization interface of OmpA (Fig. 5a). Moreover, Marcoux et al., also showed that the identified inter-linked OmpA site K213 we reported (Zheng et al., 2011) (or K192 numbering with removal of leader sequence) was critical to in vitro dimer formation (Marcoux et al., 2014). Although this Lys is not conserved in OprF, Lys residues K248 and K250 that exist nearby in the aligned OprF sequence were observed in homodimer links. Homodimeric links in this region of OprF that align with the OmpA dimerization interface suggests this region in OprF may serve a similar role in oligomerization.

Table 2.

A list of the intra-links of protein OprF. The Homodimeric intra-cross-link peptide pairs are highlighted in bold. Unique peptide pairs, and cross-linked lysine residue number of the cross-linked Lys (underlined) from each peptide is listed. Numbering of cross-linked lysine residues within a protein sequence follows the Uniprot sequence annotation, starting with Methionine as the first amino acid residue.

| Peptide 1 | Peptide 2 | Protein Uniport ID |

Gene name |

Cross- linked lysine site1 |

Cross- linked lysine site2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDFDKSK | VKENSYADIK | P13794 | oprF | 248 | 252 |

| FDFDKSK | ENSYADIKNLADFMK | 248 | 260 | ||

| SKVK | FDFDKSK | 250 | 248 | ||

| SKVK | VQLDVKFDFDK | 250 | 243 | ||

| ENSYADIKNLADFMK | 250 | 260 | |||

| NLADFMKQYPSTSTTVEGHTDSVGTDAYNQK | SKVK | 267 | 250 | ||

| QYPSTSTTVEGHTDSVGTDAYNQKLSER | SKVK | 291 | 250 | ||

| FDFDKSK | FDFDKSK | 248 | 248 | ||

| QYPSTSTTVEGHTDSVGTDAYNQKLSER | QYPSTSTTVEGHTDSVGTDAYNQKLSER | 291 | 291 | ||

| SKVK | SKVK | 250 | 250 |

Figure 5.

(a) Sequence alignment of the OmpA-like regions of PA OprF (black) and E.coli homolog OmpA (red). The sites of homodimeric intra-links in OmpA identified by in vivo cross-linking (Zheng et al., 2011; Weisbrod et al., 2013a) are indicated by dotted arrows, and the sequence region reported to be important for OmpA dimerization (Marcoux et al., 2014) is underlined (dotted line). All cross-linked Lys residues of OprF are shown in Bold. The peptide sequences containing sites of homodimeric intra-links (K248, K250 and K291) are underlined by solid lines and the corresponding cross-linked Lys residues are marked by solid arrows. Putative PG-binding sites on OprF (residues 284–297) are shown in blue. (b) Top OprF Dimer model with the shortest Xwalk distance between K248 (Red), K250 (Cyan) and K291 (Yellow). The space filled region highlights the predicted dimer interface and the aligned PG-binding site. Xwalk distances between Lys residues are shown in the table under the rotated view (c) of dimer model. See fig. S4 c–d.

To further gain information on structural orientation of the dimeric complex of OprF, a model structure of C-terminal domain of OprF monomer was predicted using I-TASSER, using a distance constraint of 35 Å between the intra-cross-linked Lys residues. The resulting top scoring model (C-score= 0.79, TM-score of 0.82± 0.08) satisfied the distance constraints for all the observed intra-links (Suppl. Fig. S4c). The predicted structure of the OprF C-terminal domain was superimposed onto the corresponding region of OmpA crystal structure (PDB identifier: 2MQE) (Ishida et al., 2014) to identify regions of variability and the two proteins showed high structural similarity, also reflected in the high TM-score of the predicted model. Importantly, the region of OmpA dimerization interface and the corresponding superimposed region of OprF monomer containing cross-link sites showed identical secondary structures. This high quality monomeric model of OprF C-terminal domain was submitted to the SymmDock to generate a symmetrical dimeric model, where homodimeric links at Lys 248, 250 and 291 were used as distance constraints between the dimerization interfaces. The resulting top twenty dimer models (Suppl. Fig. S4d) were evaluated for shortest non-linear distance between Cβ atoms of at least two of the three lysine residues (K248, K250 and K291) from each monomer (Suppl. Table 6). A dimer model of OprF with the shortest non-linear distances (Cβ-Cβ) of 9.8 Å, 11.6 Å, between residues 248, 250, respectively, and 39.6 Å between Lys 291 was retained (The Model archive DOI: ma-axj2r; Fig.5b–5c). As shown in Fig. 5c, both monomeric units of the dimer are oriented parallel to one another with their N-terminal ends that would connect to the membrane-bound β-barrel region extended towards the outer membrane (Brinkman et al., 2000) while their C-terminal globular regions reside in the periplasmic space. The putative PG-binding sites (highlighted in blue, 5c) of OprF are located within the periplasmic region in the top dimer model. This region between residues 284–297 is highly conserved within the C-terminal region of various OmpA-related outer membrane proteins including MotB from E. coli, and was proposed to be a PG-interacting site (Abergel et al., 2001). All homodimeric cross-linked sites are located in the periplasmic region and are solvent accessible, as inferred from their surface exposed positions (5c). Moreover, cross-linked Lys residues K248 and K250 are situated at the dimer interface, and their respective solvent accessible surface distances 9.8 Å and 11.6 Å are within the expected range of cross-linkable distances for the BDP-NHP cross-linker.

The results presented here reveal the first view of the high confidence PPI network in P. aeruginosa with more than 600 cross-linked peptide pairs. A large-scale interaction network such as presented here is a resource for microbiologists to examine the protein-protein interactions in greater detail in this human pathogen. For example, these results reveal previously unknown interactions among many membrane proteins, such as OprI with lipotoxins LptE and LptF. These results offer new insight on lipotoxin interactions, the roles these proteins hold in inflammation in lung epithelia, which may be involved in CF disease progression and bacterial survival in harsh environments as encountered in the colonized CF lung (Damron et al., 2009). The cross-linking sites were used to define interfacial regions of protein complexes, and enable cross-link site-directed complex structure predictions. Examples presented here were focused on the selected membrane proteins for which little other structural information currently exists. However, the network of identified cross-linked peptides can be utilized to predict structures of other proteins and protein complexes of interest using the steps described in Supplemental Figure S5. Knowledge of protein secondary structures, PPIs, and interaction interfaces can also be used to develop synthetic peptides and peptidomimetics targeting specific PPIs essential for antibiotic resistance functions.

All cross-linked peptide pairs identified in this work are presented in our on-line cross-linked peptide database XLink-DB (http://brucelab.gs.washington.edu/xlinkdb/) as a resource for the research community. The identified cross-linked sites and linkage constrains can be used with protein modeling and docking tools such as I-TASSR, PatchDock and SymmDock to predict and filter putative monomeric and dimeric protein structures. As we show for OprI, even one or two identified cross-linked peptide pairs can serve to greatly reduce the possible relative orientations of protein subunits in a multimeric complex. Recent work published by Marcoux et.al (Marcoux et al., 2014) illustrates the value of PIR cross-linking data in structural work where the previously published PIR-cross-linking results in E. coli (Zheng et al., 2011) were utilized to enable prediction of outer membrane protein A (OmpA) dimer structures. We believe that the present results may hold additional general utility to help guide future measurements using conventional structural biology techniques.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Synthesis of Protein Interaction Reporter cross-linker

The Protein Interaction Reporter (PIR) cross-linker Biotin Aspartate Proline (BDP) was synthesized with Fmoc chemistry and esterified to produce activated n-hydroxyphthalamide (NHP) ester of BDP as described previously (Chavez et al., 2013).

Two-step In vivo cross-linking

P. aeruginosa (strain PAO1) cells were cross-linked using BDP-NHP and processed as illustrated in Supplemental Fig. 1a. Cells were washed first in PBS, and then in a 170 mM Na2HPO4 pH 7.4 buffer. BDP-NHP was added to a final concentration of 10 mM and the first-step of cross-linking reaction was carried out for one hour followed by centrifugation of the cross-linked cells. The cell pellet was cross-linked as before, by adding BDP-NHP (10mM). After the reaction was over, the cells were washed extensively in PBS buffer. The cross-linking reaction was performed twice to allow for the addition of upto 20 mM BDP-NHP to increase the duration of cellular exposer to the soluble cross-linker. The cross-linked sample was further processed and analyzed by LC-MS as described in Supplemental Experimental procedures.

LC-MS analysis

LC-MS analysis was performed using reverse phase nano-UPLC (Waters, Milford, MA) coupled to a Velos-FTICR-MS (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA)(Weisbrod et al., 2013b). The Stage 1 samples were analyzed in a Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) mode. The cross-linked samples were analyzed by operating the mass spectrometer in Real-time Analysis for Cross-linking Technology (ReACT) mode (Weisbrod et al., 2013a) which optimizes analysis efficiency by focusing on cross-linked peptide ions which satisfy expected PIR mass relationships, followed by subsequent fragmentation of each of the cross-linked peptide ions (Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Identification of cross-linked proteins

A cross-linked protein enriched Stage 1 database was constructed as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. The ReACT acquisition data were searched against the Stage 1 database using SEQUEST with a variable modification of BDP-stump mass (197.032422 Da) on lysine. The resulting peptide matches were filtered at a static FDR of 5%. The retained peptide matches were mapped to their respective ReACT identified PIR relationships and peptide-pairs meeting the following criteria were retained: 1) both peptides must contain a residual BDP modification on the protein N-terminus or on an internal lysine side chain, and 2) their respective mass measurement errors must be ≤ 5 ppm.

Protein structure prediction and docking

Monomeric protein structures were predicted with I-TASSER (Zhang, 2008) using user defined distance constrains (≤35 Å) as are derived from the present cross-linking results. The resulting models were accessed for short linear distances between Cα atoms of intra-cross-linked lysines. Docking of the top monomeric models was performed using SymmDock to generate homodimeric models (Schneidman-Duhovny et al., 2005). (Schneidman-Duhovny et al., 2005). All the above steps involved in the cross-linking-derived protein structure modeling are shown in Supplementary Figure S5. Top twenty docked models were filtered based on the non-linear distances calculated using Xwalk algorithm (Kahraman et al., 2011) and were deposited into The Model Archive site (http://www.modelarchive.org/). Numbering of cross-linked lysine residues within protein sequence is consistent with Uniprot sequence annotation, starting with Methionine as the first amino acid residue.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS (limit of 4 bullets, each containing 85 or less characters including spaces).

260 binary interactions of P. aeruginosa proteins were detected in live cells

In vivo cross-linking enabled identification of membrane protein interactions

Cross-link sites enabled complex structure predictions

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants 5R01AI101307, 1R01GM097112, 5R01GM086688, and 7S10RR025107.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Abergel C, Walburger A, Chenivesse S, Lazdunski C. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic study of the peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein from Escherichia coli. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:317–319. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900019739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GA, Tolic N, Tang X, Zheng C, Bruce JE. Informatics strategies for large-scale novel cross-linking analysis. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3412–3421. doi: 10.1021/pr070035z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva A, Howorth D, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE, Hubbard TJ, Chothia C, Murzin AG. Data growth and its impact on the SCOP database: new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D419–D425. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkowitz RA, Wickner W. SecD and SecF are required for the proton electrochemical gradient stimulation of preprotein translocation. EMBO J. 1994;13:954–963. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A, Kuster B. Affinity purification-mass spectrometry. Powerful tools for the characterization of protein complexes. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:570–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman FS, Bains M, Hancock RE. The amino terminus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane protein OprF forms channels in lipid bilayer membranes: correlation with a three-dimensional model. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5251–5255. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5251-5255.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascales E, Bernadac A, Gavioli M, Lazzaroni JC, Lloubes R. Pal lipoprotein of Escherichia coli plays a major role in outer membrane integrity. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:754–759. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.3.754-759.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascales E, Lloubes R. Deletion analyses of the peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein Pal reveals three independent binding sequences including a TolA box. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:873–885. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez JD, Cilia M, Weisbrod CR, Ju HJ, Eng JK, Gray SM, Bruce JE. Cross-linking measurements of the Potato leafroll virus reveal protein interaction topologies required for virion stability, aphid transmission, and virus-plant interactions. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:2968–2981. doi: 10.1021/pr300041t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez JD, Weisbrod CR, Zheng C, Eng JK, Bruce JE. Protein interactions, post-translational modifications and topologies in human cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:1451–1467. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.024497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DS, Kim DK, Choi SJ, Lee J, Choi JP, Rho S, Park SH, Kim YK, Hwang D, Gho YS. Proteomic analysis of outer membrane vesicles derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proteomics. 2011;11:3424–3429. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui T, Zhang L, Wang X, He ZG. Uncovering new signaling proteins and potential drug targets through the interactome analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damron FH, Napper J, Teter MA, Yu HD. Lipotoxin F of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an AlgU-dependent and alginate-independent outer membrane protein involved in resistance to oxidative stress and adhesion to A549 human lung epithelia. Microbiology. 2009;155:1028–1038. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.025833-0. http://www.pseudomonas.com/p_aerug.jsp, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields S, Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firoved AM, Ornatowski W, Deretic V. Microarray analysis reveals induction of lipoprotein genes in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa: implications for inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5012–5018. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5012-5018.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll J, Rajagopala SV, Shiau SC, Wu H, Lamb BT, Uetz P. MPIDB: the microbial protein interaction database. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1743–1744. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goure J, Pastor A, Faudry E, Chabert J, Dessen A, Attree I. The V antigen of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is required for assembly of the functional PopB/PopD translocation pore in host cell membranes. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4741–4750. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4741-4750.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero C, Tagwerker C, Kaiser P, Huang L. An integrated mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach: quantitative analysis of tandem affinity-purified in vivo cross-linked protein complexes (QTAX) to decipher the 26 S proteasome-interacting network. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:366–378. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500303-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog F, Kahraman A, Boehringer D, Mak R, Bracher A, Walzthoeni T, Leitner A, Beck M, Hartl FU, Ban N, et al. Structural probing of a protein phosphatase 2A network by chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry. [02/06/2015];Science. 2012 337:1348–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.1221483. http://www.modelarchive.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H, Garcia-Herrero A, Vogel HJ. The periplasmic domain of Escherichia coli outer membrane protein A can undergo a localized temperature dependent structural transition. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1838:3014–3024. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaake RM, Wang X, Burke A, Yu C, Kandur W, Yang Y, Novtisky EJ, Second T, Duan J, Kao A, et al. A new in vivo cross-linking mass spectrometry platform to define protein-protein interactions in living cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:3533–3543. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.042630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahraman A, Malmstrom L, Aebersold R. Xwalk: computing and visualizing distances in cross-linking experiments. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2163–2164. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid S, Bond PJ, Deol SS, Sansom MS. Modeling and simulations of a bacterial outer membrane protein: OprF from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proteins. 2006;63:6–15. doi: 10.1002/prot.20845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YM, Wu SJ, Chang TW, Wang CF, Suen CS, Hwang MJ, Chang MD, Chen YT, Liao YD. Outer membrane protein I of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a target of cationic antimicrobial peptide/protein. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8985–8994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Wu C, Sweedler JV, Goshe MB. An enhanced protein crosslink identification strategy using CID-cleavable chemical crosslinkers and LC/MS(n) analysis. Proteomics. 2012;12:401–405. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux J, Politis A, Rinehart D, Marshall DP, Wallace MI, Tamm LK, Robinson CV. Mass spectrometry defines the C-terminal dimerization domain and enables modeling of the structure of full-length OmpA. Structure. 2014;22:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marianayagam NJ, Sunde M, Matthews JM. The power of two: protein dimerization in biology. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2004;29:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquordt C, Fang Q, Will E, Peng J, von Figura K, Dierks T. Posttranslational modification of serine to formylglycine in bacterial sulfatases. Recognition of the modification motif by the iron-sulfur protein AtsB. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2212–2218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209435200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T, Kageyama M. Isolation and characterization of major outer membrane proteins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAO with special reference to peptidoglycan-associated protein. J Biochem. 1979a;86:979–989. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T, Kageyama M. Isolation of characterization of a major outer membrane protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Evidence for the occurrence of a lipoprotein. J Biochem. 1979b;85:115–122. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouwen N, Piwowarek M, Berrelkamp G, Driessen AJ. The large first periplasmic loop of SecD and SecF plays an important role in SecDF functioning. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5857–5860. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.16.5857-5860.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins and intrinsically disordered protein regions. Annual review of biochemistry. 2014;83:553–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072711-164947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver A, Canton R, Campo P, Baquero F, Blazquez J. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science. 2000;288:1251–1254. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planas-Iglesias J, Bonet J, Garcia-Garcia J, Marin-Lopez MA, Feliu E, Oliva B. Understanding protein-protein interactions using local structural features. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:1210–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig O, Caspary F, Rigaut G, Rutz B, Bouveret E, Bragado-Nilsson E, Wilm M, Seraphin B. The tandem affinity purification (TAP) method: a general procedure of protein complex purification. Methods. 2001;24:218–229. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawling EG, Brinkman FS, Hancock RE. Roles of the carboxy-terminal half of Pseudomonas aeruginosa major outer membrane protein OprF in cell shape, growth in low-osmolarity medium, and peptidoglycan association. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3556–3562. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3556-3562.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawling EG, Martin NL, Hancock RE. Epitope mapping of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa major outer membrane porin protein OprF. Infect Immun. 1995;63:38–42. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.38-42.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinner O, Seebacher J, Walzthoeni T, Mueller LN, Beck M, Schmidt A, Mueller M, Aebersold R. Identification of cross-linked peptides from large sequence databases. Nature methods. 2008;5:315–318. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert V, Filloux A, Michel GP. Subcomplexes from the Xcp secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;252:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein BJ, Zeitlin PL. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 1998;351:277–282. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneidman-Duhovny D, Inbar Y, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W363–W367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu W, Liu J, Ji H, Lu M. Core structure of the outer membrane lipoprotein from Escherichia coli at 1.9 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1101–1112. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Panchaud A, Goodlett DR. Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry as a low-resolution protein structure determination technique. Analytical chemistry. 2010;82:2636–2642. doi: 10.1021/ac1000724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinz A. Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry for mapping three-dimensional structures of proteins and protein complexes. Journal of mass spectrometry : JMS. 2003;38:1225–1237. doi: 10.1002/jms.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara E, Nestorovich EM, Bezrukov SM, Nikaido H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa porin OprF exists in two different conformations. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16220–16229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600680200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Munske GR, Siems WF, Bruce JE. Mass spectrometry identifiable cross-linking strategy for studying protein-protein interactions. Analytical chemistry. 2005;77:311–318. doi: 10.1021/ac0488762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Yi W, Munske GR, Adhikari DP, Zakharova NL, Bruce JE. Profiling the membrane proteome of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 with new affinity labeling probes. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:724–734. doi: 10.1021/pr060480e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trnka MJ, Baker PR, Robinson PJ, Burlingame AL, Chalkley RJ. Matching cross-linked peptide spectra: only as good as the worse identification. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:420–434. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.034009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukazaki T, Mori H, Echizen Y, Ishitani R, Fukai S, Tanaka T, Perederina A, Vassylyev DG, Kohno T, Maturana AD, et al. Structure and function of a membrane component SecDF that enhances protein export. Nature. 2011;474:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature09980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilescu J, Guo X, Kast J. Identification of protein-protein interactions using in vivo cross-linking and mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2004;4:3845–3854. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallin E, von Heijne G. Genome-wide analysis of integral membrane proteins from eubacterial, archaean, and eukaryotic organisms. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1029–1038. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisbrod CR, Chavez JD, Eng JK, Yang L, Zheng CX, Bruce JE. In Vivo Protein Interaction Network Identified with a Novel Real-Time Cross-Linked Peptide Identification Strategy. Journal of Proteome Research. 2013a;12:1569–1579. doi: 10.1021/pr3011638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisbrod CR, Hoopmann MR, Senko MW, Bruce JE. Performance evaluation of a dual linear ion trap-Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer for proteomics research. Journal of proteomics. 2013b;88:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff WA, Hancock RE. Construction and characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa protein F-deficient mutants after in vitro and in vivo insertion mutagenesis of the cloned gene. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2592–2598. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2592-2598.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Wu YJ, Zhu M, Fan SB, Lin J, Zhang K, Li S, Chi H, Li YX, Chen HF, et al. Identification of cross-linked peptides from complex samples. Nature methods. 2012;9:904–906. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim MA, Goh KI, Cusick ME, Barabasi AL, Vidal M. Drug-target network. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1119–1126. doi: 10.1038/nbt1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Sharma KD, Takahashi T, Iwamoto R, Mekada E. Ligand-independent dimer formation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a step separable from ligand-induced EGFR signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2547–2557. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-08-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Tang X, Munske GR, Tolic N, Anderson GA, Bruce JE. Identification of protein-protein interactions and topologies in living cells with chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:409–420. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800232-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Tang X, Munske GR, Zakharova N, Yang L, Zheng C, Wolff MA, Tolic N, Anderson GA, Shi L, et al. In vivo identification of the outer membrane protein OmcA-MtrC interaction network in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 cells using novel hydrophobic chemical cross-linkers. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1712–1720. doi: 10.1021/pr7007658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Su S, Bhatnagar RK, Hassett DJ, Lu LJ. Prediction and analysis of the protein interactome in Pseudomonas aeruginosa to enable network-based drug target selection. PloS one. 2012;7:e41202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Yang L, Hoopmann MR, Eng JK, Tang X, Weisbrod CR, Bruce JE. Cross-linking measurements of in vivo protein complex topologies. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.006841. M110 006841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.