INTRODUCTION

Person-centered care is a burgeoning social movement and a mission statement for modern healthcare. However, it is not a new idea. Often called the father of modern medicine, William Osler said, “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”1 Social movements typically begin with common issues brought forward by an affected group whose members share a common interest in a cause. Health-based social movements (HSMs) such as the women's health movement and breast cancer activism have significantly impacted health and social policy.2 The movement toward person-centeredness grew from a number of narrow interest-based activists to a more general movement for healthcare reform from objections to both medicalization and medical paternalism, and the demands for increased autonomy and choice which arose from the cultural and political shifts of the 1960s.3 In addition, the increasing prevalence of long-term chronic conditions has led to the necessity of new models to manage disease and disability that empower people living with the health condition to gain greater control of their health and healthcare decisions.

In this article, we explore the concept of person-centeredness as a foundation for creating health, and examine its influence on the necessary and ongoing transformation of health care in the Western world. We will attempt to describe and operationalize the concept of person-centered care, identify factors that cause healthcare systems and individuals within those systems to behave in ways that are not person-centered and articulate steps towards a more person-centered future for US healthcare. This manuscript was culled from presentations and discussions at Patients at the Crossroads,4 a 2-day meeting of subject matter experts in healthcare systems, clinical practice, clinical education and research.

PERSON CENTEREDNESS

An adage that came out of an international conference in Salzburg in 1998 “Nothing about me without me”5 has been the rallying cry of the person-centered care movement. At that conference, patient-advocate social scientists assembled to share thoughts and research on biomedicine and informational medicine. Their conclusion was that an individual's hopes, expectations, beliefs, cultural norms, and life goals must guide the plan of care. The person is the driver in creating health and maintaining and promoting optimization of wellness and wellbeing. Person-centric systems are needed to deal with inevitable trauma and illness, both issues that we as humans face, but in a way that honors the individual and acknowledges each person's rights and responsibilities to make their own decisions and exercise their autonomy.

One way that HSMs have impacted health and social policy is to control the terms of the discourse. Language is a powerful tool to shape and change systems and policy. For example, insisting that women who have a history of breast cancer be referred to as “breast cancer survivors” rather than “breast cancer victims” empowers them and forces scientists, physicians, and funders to recognize them as individuals with the authority to speak.2 This is particularly true in the terminology we use to describe individuals who come to healthcare for assistance and the professionals who care for them.

The word “patient” derives from the Latin patiens, which means to suffer, endure, or submit. The underlying connotation of passivity remains. Conversely, “doctor” derives from docere, meaning “to teach,” implying a didactic relationship. “Nurse,” unsurprisingly, derives from nutrire, meaning “to nourish.” Taken as a whole, this language suggests a passive role for patients; a patient receives and a doctor, nurse, or other healthcare professional provides. In this context, the concept of “patient-centered care” is almost a contradiction. In truth, some but not all patients suffer and endure, and even those that do are not defined by these experiences. It may be appropriate, particularly given the Whorfian implications of this language to consider a broader term, such as “person-centered.” Person indicating an individual human being with a unique history and particularities such as family, genetics, communities, cultures and personal narratives. The term person also denotes the shared experiences of all humans, their personhood. According to Cassell, universal attributes of personhood includes “the ability to form relationships, curiosity, the need for control, the need to be loved and to be needed, dignity, and honor.”6(p117) Indeed, the relationships of physicians and their patients are more complex and varied than the underlying language would suggest. The term person refers to being healthy as opposed to sick like a patient and being able to fully engage in meaningful relationships and transcendent purpose.

William Miller described four different categories of clinical relationships: patient-clinician; client-expert; consumer-provider; and person-person (Table 1). By understanding these relationships we can cultivate the right relationship at the right time, a critical factor to improve communication, manage critical decisions, and optimize the potential for healing.7–9 In essence, patients, consumers, clients are persons in particular circumstances; the patient needs a doctor or a clinician; the client needs a professional expert; the consumer needs a provider; and the person needs another person.3 These four are aspects of a dynamic process of relational shifting, in other words, various forms of adaptive partnerships with ever shifting roles and contexts. The nature of the relationship can change within a single encounter, over the course of an episode of care, and multiple times over a lifetime depending on the perceived needs, degree of sickness, and expectations. Each party to the relationship can initiate the shift. Failure of both parties to recognize and agree on what type of relationship exists at a given time will impact the effectiveness of the clinical relationship. Independent of the application of professional expertise or healthcare products, services and care, healing occurs in the relational, person to person context.9,10 The language we use and the labels we assign delineate the relationship. Person-centered care requires a care system with structures and processes that support the development of appropriate relationships at the appropriate times in order to meet patient goals.

Table 1.

Clinical Relationships

| Relationship | Situations | Power Gradient |

|---|---|---|

| Person-Person | Individuals seeking advice to optimize health and wellbeing A patient's support team working with the clinician on the plan of care | Shared power, shared decision-making |

| Consumer-Provider | Individuals attempting to purchase a commodity, for example medication, products or services | Consumer may discuss or negotiate with the provider but makes the decisions and utilizes the products they acquire |

| Client-Expert | Individuals seeking a professional expert or specialist and has options from which to choose | Client has the greater power in the decision to access the expertise of the clinician |

| Patient-Clinician | Sick persons in need of care and medical expertise | There are degrees of shared decision-making from full partnership to significant clinician control. This relationship is bound by a sacred covenant with the special obligations and expectations of professionalism. |

Another way that HSMs gain momentum is to coalesce around common issues and goals and become more organized and strategic.11 The growing burden of chronic illness on individuals, families and society, coupled with social-cultural shifts provide common ground for the person-centered care movement. These needs are balanced using the quadruple aim.

THE QUADRUPLE AIM

Don Berwick described the “Triple Aim” as a set of organizing principles for healthcare delivery: improving the patient experience of care, improving population health, and reducing costs.12 Tom Bodenheimer and Christine Sinsky have added a fourth aim: improving the work life of those who deliver care, in other words; practice joy, since a healthy population requires a healthy workforce.13 Originally defined in the context of military medicine, force readiness also called collective readiness, is interconnected with these three and enhances their achievement.14,15

PATIENT EXPERIENCE

The patient experience of care is impacted by healthcare quality and safety as well as the patient's perception of the experience as healing. Multiple levels of integration are necessary to improve the patient experience of care.16,17 Levels of integration include integration of health factors—physical, psychological, social, preventive, and therapeutic; integration across the lifespan—personal, predictive, preventive, and participatory care; integration of care processes, across caregivers and institutions; and integration across approaches to care—conventional, traditional, alternative, and complementary.18 Modern healthcare systems include many specialized professionals that collaborate through complex networks. Effective communication and collaboration among them are critical for patient safety and improved quality and lead to a cohesive experience for the patient, rather than multiple disparate or even contradictory experiences.19 Integration of the patient and their community—which includes the patient's friends and family, neighbors, workplace, and school in care and care decisions—is central to person-centered care.16

POPULATION HEALTH

Population health is traditionally defined by disease prevalence and other epidemiological measures. However, salutogenesis or health creation is the ultimate goal of the quadruple aim.20,21 The term was coined as a counterpoint to the classical concept, pathogenesis.22,23 Pathogenesis describes deleterious physiological processes that create disease states, ill health, and characterize breakdown of physical and mental function over time. Medical education, research, and practice are largely organized around pathogenesis; students learn about pathogenic states, research funding is driven towards mechanisms of pathogenesis, and even reimbursements are dispersed for treatment of pathogenic diagnoses. Salutogenesis, conversely, refers to health creation and healing. Salutogenesis describes processes that create health and promote healing; salutogenic processes are preventative, restorative, and palliative in nature.24 The rational application of the full range of available clinical interventions, including pharmacy and surgery, but also lifestyle interventions, psychotherapy, and a range of complementary and integrative (CIM) medicine promotes salutogenesis.

COST OF CARE

Cost of care, expressed in per capita terms, is the third issue in the quadruple aim. Total spending on healthcare in the United States by both the public and private sectors was $2.9 trillion in 2013, accounting for 17.4% of the economy devoted to health spending.25 Americans currently pay about twice as much per capita on healthcare as our peers do in other advanced nations, yet our health outcomes are no better.26 Disconnected and uncoordinated care amplifies the economic burden of the health care system.18 The cost of care is often invisible to the person receiving the care as are the decisions on coverage for care.

COLLECTIVE READINESS

Collective or force readiness refers to individual and collective wellbeing or resilience. Readiness indicates not merely a state of health but a state of being prepared to withstand challenges and achieve personal goals, the ability to balance assets and the demands of life.13,27 Moving from clinician driven medical care to self-management necessitates new problem-solving skills. Strong self-efficacy has been found to predict positive outcomes and a better prognosis, and weak self-efficacy predicts long-term disability.28,29 The military defined readiness as “ensuring that the total military force is medically ready to deploy and that the medical force is ready to deliver health care anytime, anywhere.”30(p30)

Readiness applies to those who deliver care and involves finding joy and meaning at work and support to enable self-awareness and meaningful partnerships.3,13 Readiness of the healthcare workforce is critical to achieve the goals of the triple aim. Dissatisfaction and burnout among health care workers is associated with lower patient satisfaction, contributes to overuse of resources and thereby increased costs of care, and lower levels of empathy with associated reduced adherence to treatment plans by patients.13,31–33 The positive engagement, rather than the negative frustration, of the healthcare workforce has significant influence on the aims of better care, better health, and lower costs.13

HSMs challenge the scientific and medical establishments to empower people to gain greater control of their health.2 To meet the person-centered goals represented by the Quadruple Aim, person-centered care involves the right relationship at the right time; acknowledges the individual as an expert in their care; and supports shared decision-making and responsibility for health creation. However, achieving person-centered care is not without its challenges.

CHALLENGES

The process of delivering healthcare is inherently difficult. Time, money and capacity are constraining factors on any measure of healthcare quality. Moreover, physicians and other health professionals face the same challenges as any other people, and their personal stresses can affect their professional output. In addition, there are systemic challenges to delivering person-centered care, some manifest in policy and others implicit in the culture of healthcare. Important examples are presented below.

COMPLEXITY

An aging population and the resultant complexity of health problems and health information are salient and closely related challenges. Increased life expectancies have led to a high demand for long-term care services. These services are not strictly medical, and indeed 85 percent of long-term care services are delivered in the home and are important to health.34 Advocacy groups have resisted integration between long-term care providers and healthcare organizations based on the complex financing issues.35

Complex health problems do not follow a normal statistical distribution. They are more accurately conceptualized in exponential terms, and are better described through power laws. The 80/20 rule suggests that roughly 20% of people account for 80% of all healthcare costs. In practical terms, this suggests that complex patients, those with chronic illnesses, comorbidities, and other clinically challenging problems, are high utilizers of care, and are important targets for improvement on all four of the quadruple aims.36

MISALIGNED INCENTIVES

The fee-for-service model is the current standard for reimbursement by both private and public payers in the US healthcare system. Payment for most services is authorized only when the patient's problem exceeds a diagnostic threshold; preventive or self-care is not highly reimbursed if at all. In practice, payment rendered is based on complex documentation rules that rarely reflect the actual delivery of service. This has incentivized an increase in the number of accepted diagnoses. The official system used for coding US hospital utilization increased from 20,000 codes in the ICD-9-CM to more than 140,000 codes in the ICD-10-CM.37 This process may substantially improve identification or description of serious pathological states but has also been implicated in the increasing medicalization of non-pathologic states.38 The payment model incentivizes medical interventions and is a disincentive for salutogenic approaches in primary care.39,40 Other payment models exist, each with advantages and disadvantages. Examples of alternative payment models include bundled payment, global budgets and capitation.

CREATING AUTHENTIC PARTNERSHIPS

Patients living with long-term conditions benefit by working with their health professionals in a partnership founded on the recognition of the person as an expert in their own experience of the condition and where the individual's priorities are understood.41,42 “An ‘authentic partnership’ actively incorporates and values diverse perspectives and includes all key stakeholder voices directly in decision-making. It involves working with others, not for others.”43 Authentic partners are characterized by genuineness, commitment and mutual respect. They build on strengths and assets and balance inherent power gradients to address needs and build capacity.44 Authentic partnerships require a foundation of effective communication, shared decision-making and goal setting, leading to mutual trust and respect.

Authentic partnerships and healing relationships are very difficult to develop and maintain when the clinicians involved are stressed. Cynicism and lack of compassion are early symptoms of clinician burnout. The problem begins early in healthcare professionals' careers. Medical and nursing students experience high levels of stress, burnout and a degradation in empathy over the course of their education.45–48 Traditional teaching methods have not modeled partnerships, shared decision-making or compassion. The curricula in schools that prepare health professionals are overloaded with content and the predominant mode of education has been passive and not particularly learner-centered. Experienced clinicians also experience high levels of stress, empathy degradation and even higher than average rates of PTSD leaving little energy to develop authentic partnerships with patients and colleagues.49,50

Medical communication is fraught with substantial jargon, adding to many other culturally-driven differences in language and communication style. Person-centered care requires that the involved parties communicate effectively, but conveying complex and emotionally difficult information thoroughly and with nuance and sensitivity is difficult. Limited time and extensive procedural requirements are further barriers to effective communication. Communication between healthcare professionals is also a challenge and impacts the patient directly when information is not consistently conveyed. Inpatient care requires frequent hand-offs where clinicians leave at the end of their shift and transfer patient care responsibilities to the next person. Integrated care requires that many different professionals interact: physicians of different specialties, clinicians from diverse philosophies, as well as allied professionals, and other pertinent staff.

The Health Information Privacy Assurance Act (HIPAA), while crucial in its own right as a protector of patient privacy, is perceived by some as a barrier to integrating patient care. Because of perceived HIPAA restrictions, difficulties have been noted both in effective communication among teams of care and in gaining patient consent and conveying information to people related to the patient.51

Mutual trust among all involved parties is foundational to building the relationships involved in person-centered care. However, significant ethical breaches by healthcare researchers have damaged that trust. In particular, widespread knowledge of the Tuskegee experiments, the use of Henrietta Lacks's DNA, and other incidents may have engendered a distrust of medicine in minority communities. Compromises in trust are by no means limited to research. Patients are often excluded from key health decisions, both in the context of individual medical care and more broadly in the way care delivery systems and research are administrated. This may represent a deficit of trust on the part of healthcare professionals, as well as a variety of pragmatic considerations. The inclusion of patient representatives on health system boards and planning committees is a step in the right direction but has not been widely adapted.

PATIENT PRIORITIZED EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Since the Flexner report of 1910, medical education and practice has relied heavily on biomedical research as the source of new knowledge and best practices.52 Biomedical research is focused largely on measuring efficacy, as a proof of concept in novel therapeutics. While this information has value, highly controlled efficacy studies may not provide all the information needed to practice medicine that is both evidence-based and person-centered. The clinical relevance of even well-conducted studies is not guaranteed, particularly when benchmarked against patient prioritized outcomes. This becomes a challenge when the desires of patients and families to participate in their care decisions conflict with existing evidence-based practice guidelines.53 For example, a randomized controlled trial comparing surgical methods of hernia repair collected various standard clinical outcomes. However, it also conducted a qualitative assessment at the conclusion of the study, and asked patients what factor they would use to choose between surgical options. The most popular answer, endorsed by 74 percent of the patients, was that they would choose the option least likely to lead to a second surgery.54,55 While this is an objective measure, none of the quantitative data collected assessed this question.

For diverse, complex patients in non-standardized settings, clinical trials may not provide adequate information on practical, long-term outcomes and most certainly do not provide information on self-care and self-management techniques. Person-centered care and evidence-based guidelines are in conflict when the research-based evidence was not driven by patient-prioritized questions and desired endpoints.

DIRECTIONS

American healthcare is changing rapidly, as a result of shifting health challenges, technological advancements, and policy changes. There are many possibilities as a result of these changes; a more person-centered healthcare system, a more complex and challenging system; or the status quo could prevail. Formalizing the person-centered care movement will require more organization and coalition-based strategies.11 A support structure of education, research, and delivery systems to support person-centered care is critical. The following are proposals and exemplars of transformational change directed toward person-centeredness in four vital areas: healthcare systems, clinical practice, clinical education, and research.

HEALTHCARE DELIVERY SYSTEMS

How do we move toward a comprehensive and holistic reunification of the patient and the person within a system that's devoted to maintaining this integrity while promoting the optimal degree of health and wellbeing? Saying that the culture must change is insufficient. Instead, we must develop structures and processes that will result in the desired outcomes described by the quadruple aim: improving the patient experience of care; improving population health; reducing costs12; and improving the work life of those who provide care, joy at work, all enhanced by force readiness manifested as resilience.13–15,27 Person-centered healthcare systems combine the best in medical diagnosis and treatment with self-care that is educational and enhances our innate healing abilities. In addition, they balance health creation and disease management; create partnerships between experts and patients; generalists and specialists; and tap into the talent of each individual allowing each to participate to the fullest extent of their abilities. Thus it is crucial that lay persons are involved in decision-making.

To meet this challenge, the healthcare reform movement has generated several healthcare system models including the patient-centered medical home, specialty care models, and community integration systems.

Patient-centered Medical Home

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) has attracted significant attention as a model for primary care delivery in both hospital and private practice settings, recognizing the attributes already present in primary care and advancing innovations. Four core features of a PCMH include the delivery of primary care (including comprehensive, initial access, coordinated, personal care), changes in practice organization, development of practices' internal capabilities, and broader systemic changes, including in reimbursement.56 Outlined in Table 2 are 4 types of PCMH that William Miller found in his review of more than 100 pilot projects. Interestingly, with the exception of one example of the integrative PCMH, the models studied improved slightly in condition-specific quality of care but did not improve the experience of the patients served.57 With PCMH in its early stages, the transformation is still emerging and outcome improvements will evolve.58

Table 2.

Patient-centered Medical Home (PCMH) Models

| PCMH Model | Description |

|---|---|

| Add-on | The add-on PCMH preserves the existing primary care practice and adds a shared system for electronic medical records and a case manager. |

| Renovated | A renovated PCMH changes elements internal to the practice, adding new technical capabilities, staff expertise, or workflow changes. |

| Hybrid | A hybrid PCMH combines the improved electronic communication and coordination and the internal practice improvements of the add-on and renovated models. |

| Integrated | An integrated PCMH, like a hybrid, improves both internal records and communication and adds new capabilities but also fully integrates them and incorporates additional types of care not found in conventional practices, such as mental health care and/or complementary and alternative modalities. It may also be characterized by community inclusion and multidimensional care delivery. |

Southcentral Foundation's “Nuka System of Care” is an exemplar of integrated PCMH demonstrating improved health outcomes in the community it serves. This health care system is a community-owned, nonprofit organization; it is neither a business nor a government program, and it was created to supplant the Indian Health Service. An extensive live-in orientation is required for all staff, from physicians to receptionists. Care is delivered in a dimensional fashion as described above, with lay health workers, nurses, and physicians coordinating care depending on the extent of the patient's needs.

Specialty Care Models

Outside of primary care practices, person-centeredness is no less important. While the issues involved in delivery of specialty care are diverse, team-based, integrated care is possible. A compelling example of person-centered, team-based care comes through the amputee clinics run by the military health care system. Multiple analyses of length of inpatient hospitalizations found that the number of comorbid diagnoses strongly predicted length of hospitalization.59–62 An exception to these findings is amputees enrolled in military amputee care. The military amputee care model demonstrates strong team-based care, with physicians, physical and occupational therapists, prothestists, and a variety of other professionals collaborating closely, regularly, and efficiently. It has also established a strong positive culture, with social interactions, judicious use of humor, and an emphasis on setting high goals for recovery.

Community Integration Model

In Memphis, Tennessee, an excellent example of community integration in health care has been achieved through recruiting local faith-based organizations to form the Congregational Health Network (CHN). The network bridges the racial and cultural barriers to continuity of care that led to a higher read-mission rate for African Americans than the rest of the population served by Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare. The network of 400 churches in Memphis provides holistic health care services including social care, discharge planning, and assistance after inpatient hospitalization. CHN uses volunteer health liaisons to arrange post-discharge services and hospital-to-home transitional assistance. An analysis of 473 CHN participants compared to matched non-enrolled patients demonstrated lower mortality, lower utilization of inpatient services and higher patient satisfaction.63

PRACTICE

The delivery of person-centered healthcare in practice is ultimately manifest through the interaction between a healthcare professional and a patient. An important lesson from the PCMH demonstration projects was shifting away from ineffective disease management strategies to more effective care management approaches that prioritize high risk sub-populations. As noted earlier, twenty percent of the population represents eighty percent of healthcare costs and the highest risk. Those twenty percent are not characterized by a particular disease but by multi-morbidity, mental health problems, and limited social resources. These individuals are the focus of Integrated PCMHs. Another, somewhat surprising high risk group includes the well-insured, well-educated who are most satisfied with their current care; it turns out they are the highest utilizers and have a higher mortality, most likely from iatrogenic over-utilization.64

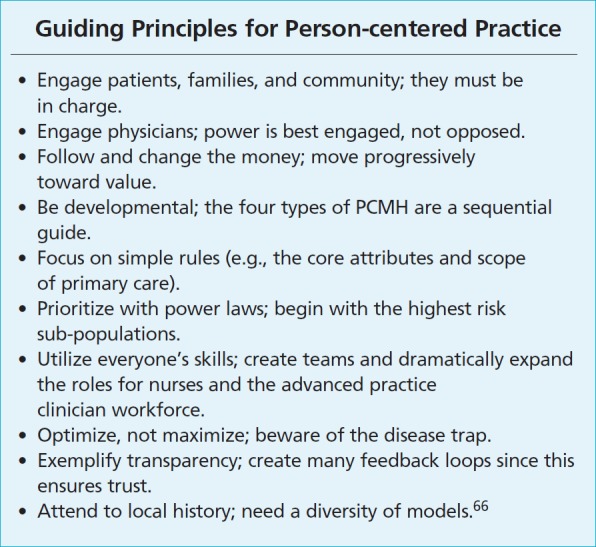

Relationship-centered primary care practice focuses on the right relationship at the right time as described earlier. If we learn from the past, heed the key lessons from PCMH pilots,8 follow simple rules,65 and turn our energies towards a goal of “helping individuals, families, and communities achieve THEIR goals for living life as they want to live,” we will move toward person-centered care and health creation. Figure 1 provides 10 principles for guiding person-centered practice.66

Figure 1.

Ten rules for relationship-centered primary care practice.

Life is a long journey, as is health and healthcare. It covers a lifespan within social, religious, and family contexts and is highly influenced by values, beliefs, habits, and outside voices. We therefore need effective, long-term, trusting, accountable, personal relationships to succeed on that journey. When our primary care practice is engrossed in the health of each person within the web of their supportive relationships, we will experience the prosperity of person-centered care.

EDUCATION

What educational structures and processes are needed to train healthcare professionals to become person-centered, relationship-centered, evidence-based, and maintain high levels of scientific and technical competence? When we think of person-centered care, the words and phrases that come to mind are caring, compassion, empathy, safe, effective, coordinated, comprehensive, and aligned with the patient's needs, preferences and values. This requires clinicians and care providers with a different set of knowledge, skill and attitudes. At this point in time, we have put far more emphasis on fixing the system of healthcare that produces the product we are not satisfied with (ineffective, uncoordinated and unsafe care), than the educational system that has produced the clinicians who provide the care. We need a shift in the educational paradigm that is at least as bold and radical as the change being called for in the healthcare system. We can't continue with the same educational processes and expect changes in outcomes. Person-centeredness starts with the way in which we learn our craft, not only in the content but in how we learn and with whom. Person-centered care requires clinicians skilled in relationship building, empathy, compassion and clinicians who can work well in interdisciplinary teams.

Content

Existing medical education standards heavily reference physical and life sciences. Preparing future clinicians to be person-centered, develop authentic partnerships and practice in interprofessional teams requires new content and rebalancing of content emphasis.

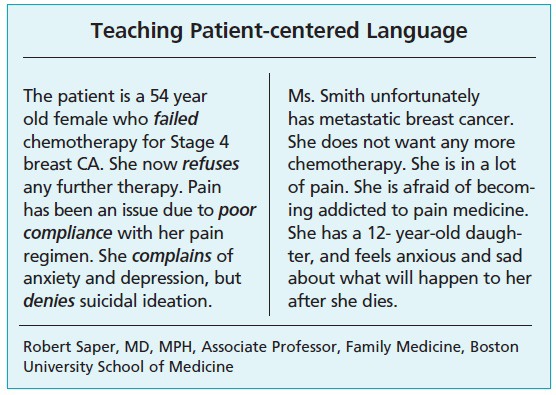

Communication has been raised repeatedly as an important competence that requires further emphasis. Importantly, communication includes both the receiving of information as well as conveying it. Effective communication skills are critical to develop healing relationships and require active listening, reflection, being fully present in the moment, a non-judgmental attitude, and the ability to value the person as an individual. Being able to communicate in common language as well as with technical terms is an important competency and using patient centered language takes a shift in thought processes. As Figure 2 demonstrates, clinician-centric case presentations paint a different picture from patient-centric presentations and lead to different care plans.67

Figure 2.

Patient-centered language.

Taking a patient history is a foundational element of the medical and nursing curriculum. However, the traditional medical history focuses on present symptoms and does little to elicit patient goals and priorities. Table 3 illustrates the difference between standard and person-centered medical history.

Table 3.

Comparison of Standard and Patient-centered Medical Histories

| Standard Medical History | Patient-centered Medical History |

|---|---|

| Chief complaint | Chief complaint, goals, and concerns |

| History of present illness | History of present illness |

| Past medical and surgical history | Past medical and surgical history, use of complementary and alternative care modalities |

| Medications | Medications, herbs, supplements, and self-care activities |

| Allergies | Allergies and sensitivities |

| Family history | Family history and background |

| Social history: occupation, marital status, tobacco use, alcohol use, drug use | Social history: occupation, marital status, tobacco use, alcohol use, drug use, relationships, stress, diet, exercise, sleep, spirituality |

Transformational Learning

How we teach is as critical as what we teach. There are parallels between person-centered practice and learner-centered education. There are two basic forms of learning according to developmental psychologist Drago-Severson68: informational and transformational. In the United States and around the world, informational learning has been by far the dominant paradigm. The curricula in schools that prepare health professionals are overloaded with content and the predominant mode of education has been passive and not particularly learner-centered. Acquisition of skills for effective practice is a necessary part of professional development, but professions are distinguished from skills-based work by development of professional artistry.69 It would be unnatural, then, to expect a practitioner educated by experts who “tell” more than guide or coach to bring any other relationship dynamic to his or her clinical practice.

Transformational learning involves the learner considering multiple viewpoints, questioning their own assumptions, beliefs, and values, and verifying their reasoning.70 Transformational learning requires a learner-centered experiential curriculum that incorporates reflective practice, mindfulness and learning through service as key strategies. Using reflective techniques for skill development not only improves clinical practice but provides self-care skill development that may prevent or mitigate stress and burn-out.71 Table 4 compares instructional and transformational learning systems.

Table 4.

Comparison of Instructional and Transformational Learning Systems on Learning and Clinical Care

| Conventional System | Care Delivery System | Clinical Education |

|---|---|---|

| Role of the Patient/Student | Passive recipient of care | Passive recipient of education |

| Role of the Provider/Teacher | Expert | Expert |

| Key Intervention/Strategy | Telling them what to do | Lecturing/Telling them what to do |

| Impact on Behavior | Compliant/Non-compliant | Pass/Fail |

| Transformed System | ||

| Role of the Patient/Student | Active participant, empowered and engaged | Active participant, empowered and engaged |

| Role of the Provider/Teacher | Guide, coach, and facilitator | Guide, coach, and facilitator |

| Key Intervention/Strategy | Coaching, motivating, and engaging | Coaching, motivating, and engaging |

| Impact | Healing | Learning |

While traditional medical education involves a rotating series of clinical clerkships, the Harvard–Cambridge Health Alliance created a longitudinal clerk-ship that allows students to maintain close and continuous contact with specific patients over the course of a year rather than several weeks.72,73 Compared to traditional clerkships, the longitudinal model has resulted in increased performance assessments, greater satisfaction, and a stronger sense of person-centeredness in students completing it.74 Person-centered care requires professional artistry and is developed through learner-centered education that is transformative and incorporates the framework of reflective practice.

Interprofessional Education

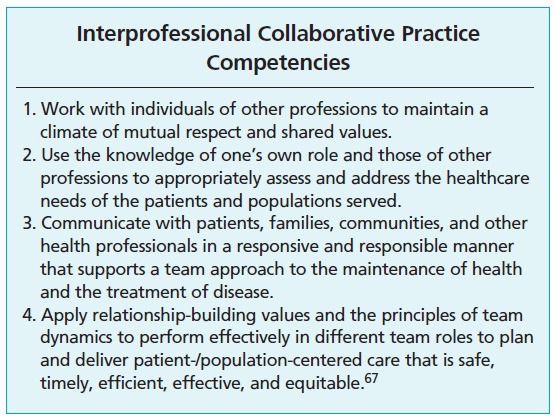

Increasing specialization and divergent professional paths mean that a single healthcare professional, no matter how talented or skilled, cannot subsist alone. Building teams with diverse competencies is essential to fulfill patients' needs. Interprofessionalism must start at the educational level. The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) was formed in 2009 to promote and encourage efforts to advance interprofessional learning. The IPEC developed core competencies to advance interprofessional learning experiences and help prepare future clinicians for team-based care (Figure 3). The competencies track to 4 core areas: values and ethics for interprofessional practice; roles and responsibilities; interprofessional communication; and teams and teamwork. Person-centered care requires professional teams that communicate and share resources and expertise efficiently and effectively, and those skills must be developed during professional education.

Figure 3.

Interprofessional collaborative practice competencies.

Elective courses within the medical curriculum are low-hanging fruit; it is easier to add elective material than to change the core curriculum of a highly standardized program. With that in mind, one example of such a course with explicitly person-centered themes is the Healer's Art elective at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), which uses reflection exercises in small interdisciplinary groups to cover content including restoring balance, grief and loss, and service.

PERSON-CENTERED RESEARCH

Creating more person-centered research endeavors involves a variety of considerations. Person-centric research designs assess patient prioritized outcomes over time periods appropriate to patients, rather than short-term outcomes that are more funder- and research-centric. Pragmatic research designs include diverse patient populations and study treatments as they naturally occur. Qualitative and mixed-methods studies in natural settings collect a depth of patient information not available through controlled experimental designs and quantitative methods alone. Person-centered research focuses on outcomes that patients deem important and asks the difficult questions related to meaningful benefit. Patients want to become more involved in setting research priorities and adjudicating ethical questions. Specific examples of person-centered research reforms include the establishment of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and the National Prevention Council (NPC).

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) established PCORI explicitly to increase the availability of person-centered research data. This granting agency is focused on funding pragmatic and comparative trials that shift the prevailing bio-medical centric focus to person-centric research. PCORI operates in parallel with existing government agencies and private interests funding biomedical research.

The NPC was established by the ACA, including representation from 17 different agencies, with a mission to translate the National Prevention Strategy into actionable plans. An Institute of Medicine (IOM) report outlined the need to develop new standardized outcome measures for prevention processes. Given additional incentives and resources, research focusing on salutogenesis may receive more support.

CONCLUSIONS

Person-centeredness is a health-based social movement that grew from frustration about medical paternalism, concerns about the rising costs of healthcare without corresponding improvements in health, and growing consumerism.2 Like all social movements, the person-centered care movement is chaotic and noisy with many voices raised in protest against the current system. The current disease management system provides good medical care when the problem is acute and short term but the successes of the current system are manifest in the numbers of baby boomers with chronic diseases, diseases that result from a lifetime of poor health behaviors. Transformative change is needed in the way we manage and provide care, educate clinicians and generate evidence for practice if we are going to achieve the goals of the quadruple aim; enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing costs while enhancing collective readiness to care for themselves and others.

The person-centered care movement is a demand for a health solution, a solution that involves each individual in health creation and participation in their care to the best of their abilities. A philosophical shift towards health creation is a priority, to complement elimination of disease and improve the health of the population. Person centeredness should be the driving force for healthcare system reform, clinical practice, education and research. The person-centered care movement has generated innovation in models of care, practice norms, clinical education and research. Examples include integrated patient centered medical homes, integrated specialty practices, community based support to the chronically ill and relationship based care models. These innovations are supported and spread through interprofessional education advances and learner-centric educational models as well as patient-centered research.

The quadruple aim is within our reach. Our understanding of person centeredness and ability to hardwire person centeredness into practice requires (1) policy changes that incentivize healthcare systems, clinicians and patients for providing and utilizing primary care, preventative, and self-care health promotion activities; (2) systematic inclusion of patients and family perspectives in healthcare system decisions, best practice evidence generation and clinical education; and (3) learner-centric clinical education that integrates relationship skill building with the scientific curricula.

A focus on policy, people, research, and education will enable person-centered care to re-emerge as a value, to drive quality and safety, to serve as a goal for the way we prepare health professionals to practice in the 21st century, and to meet the quadruple aim.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under the IC4 Program, Award No. [W81XWH-07-2-0076]. The views, opinions and/or findings contained in this report are those of the author(s) and should not be construed as an official Department of the Army position, policy or decision unless so designated by other documentation. The authors would like to acknowledge John Bingham, Barbara Findlay Reece, and Kelly Gourdin for their help in synthesizing the information presented during the Patients at the Crossroads symposium.

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and had no conflicts to disclose.

Contributor Information

Bonnie R. Sakallaris, Samueli Institute, Alexandria, Virginia (Dr Sakallaris), United States.

William L. Miller, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, Pennsylvania (Dr Miller), United States.

Robert Saper, Boston University School of Medicine, Massachusetts (Dr Saper), United States.

Mary Jo Kreitzer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis (Dr Kreitzer), United States.

Wayne Jonas, Samueli Institute, Alexandria, Virginia (Dr Jonas)), United States.

REFERENCES

- 1.Silverman ME, Murray TJ, Bryan CS. The quotable Osler. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keefe RH, Lane SD, Swarts HJ. From the bottom up: tracing the impact of four health-based social movements on health and social policies. J Health Soc Policy. 2006;21(3):55–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes JC, Bamford C, May C. Types of centeredness in health care: themes and concepts. Med Health Care Philos. 2008. December;11(4):455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patients at the crossroads: reconciling person-centered care, evidence-based practice and integrative medicine. Paper presented at: Patients at the Crossroads: Reconciling Person-Centered Care, Evidence-Based Practice and Integrative Medicine 2012; Alexandria, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—pinnacle of patient-centered care. New Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassell EJ. The healer's art. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinn JF. The self as healer: reflections from a nurse's journey. AACN Clin Issues. 2000. February;11(1):17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Stange KC, Jaén CR. Primary care practice development: a relationship-centered approach. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8 Suppl 1:S68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott JG, Cohen D, DiCicco-Bloom B, Miller WL, Stange KC, Crabtree BF. Understanding healing relationships in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):315–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koloroutis M, Trout M. See me as a person: creating therapeutic relationships with patients and their families. Minneapolis, MN: Creative Health Care Management; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christiansen J. Four stages of social movements. EBSCO Research Starters. 2009. https://www.ebscohost.com/uploads/imported/thisTopic-dbTopic-1248.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2015.

- 12.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008. May-Jun;27(3):759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter CL, Goodie JL. Behavioral health in the Department of Defense patient-centered medical home: history, finance, policy, work force development, and evaluation. Transl Behav Med. 2012. September;2(3):355–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stinner DJ, Sathiyakumar V, Ficke JR. The military health care system: providing quality care at a low per capita cost. J Orthop Trauma. 2014. October;28 Suppl 10:S11–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortney L, Rakel D, Rindfleisch JA, Mallory J. Introduction to integrative primary care: the health-oriented clinic. Prim Care. 2010. March;37(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman PM, Dodds SE, Logue MD, et al. IMPACT—Integrative Medicine PrimAry Care Trial: protocol for a comparative effectiveness study of the clinical and cost outcomes of an integrative primary care clinic model. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014. April 7;14:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine. Integrative medicine and the health of the public: a summary of the February 2009 summit. Washington, DC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maizes V, Rakel D, Niemiec C. Integrative medicine and patient-centered care. Explore (NY). 2009. Sep-Oct;5(5):277–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rakel D. The salutogenesis-oriented session: creating space and time for healing in primary care. Explore (NY). 2008;4(1):42–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellery J. Integrating salutogenesis into wellness in every stage of life. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007. July;4(3):A79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan K-K, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, Chan SW-C. Integrative review: salutogenesis and health in older people over 65 years old. J Adv Nurs. 2014. March;70(3):497–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antonovsky A. Health, stress, and coping. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonas WB, Chez RA, Smith K, Sakallaris B. Salutogenesis: the defining concept for a new healthcare system. Global Adv Health Med. 2014;3(3):82–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartman M, Martin AB, Lassman D, Catlin A. National health spending in 2013: growth slows, remains in step with the overall economy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(1):150–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.OECD. Total expenditure on health per capita 2014/1. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/total-expenditure-on-health-per-capita-2014-1_hlthxp-cap-table-2014-1-en. Accessed December 23, 2015.

- 27.Tiliouine H, Cummins RA, Davern M. Measuring wellbeing in developing countries: the case of Algeria. Soc Indic Res. 2006;75(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Pietro F, Catley MJ, McAuley JH, et al. Rasch analysis supports the use of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire. Phys Ther. 2014. January;94(1):91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson T, Wang Y, Wang Y, Fan H. Self-efficacy and chronic pain outcomes: a meta-analytic review. J Pain. 2014. August;15(8):800–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Military Health System Review—final report. August 29, 2014. http://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety/MHS-Review. Accessed December 23, 2015.

- 31.Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? J Gen Intern Med. 2006. June;21(6):661–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider J, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Li W, Wilson IB. Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to anti-retroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1096–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neri L, Brancaccio D, Rocca Rey LA, Rossa F, Martini A, Andreucci VE. Social support from health care providers is associated with reduced illness intrusiveness in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2011;75(2):125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen MA. Emerging trends in the finance and delivery of long-term care: public and private opportunities and challenges. Gerontologist. 1998. February;38(1):80–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai J, Harpaz-Rotem I, Pietrzak RH, Southwick SM. The role of coping, resilience, and social support in mediating the relation between PTSD and social functioning in veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychiatry. 2012. Summer;75(2):135–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sturm AC., Jr Betting on the 80/20 rule. Healthc Financ Manage. 2005. July;59(7):112–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manchikanti L, Falco FJE, Hirsch JA. Ready or not! Here comes ICD-10. J Neurointerv Surg. 2013. January 1;5(1):86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott-Samuel A. Less medicine, more health: a memoir of Ivan Illich. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003. December;57(12):935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berenson RA, Kaye DR. Grading a physician's value—the misapplication of performance measurement. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2079–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berenson RA, Rich EC. US approaches to physician payment: the deconstruction of primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010. June;25(6):613–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cudney S, Weinert C, Kinion E. Forging partnerships between rural women with chronic conditions and their health care providers. J Holist Nurs. 2011. March;29(1):53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korda H, Erdem E, Woodcock C, Kloc M, Pedersen S, Jenkins S. Racial and ethnic minority participants in chronic disease self-management programs: findings from the Communities Putting Prevention to Work initiative. Ethn Dis. 2013. Autumn;23(4):508–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dupuis S, Gillies J, Carson J, Whyte C. Moving beyond patient and client approaches: Mobilizing ‘authentic partnerships’ in dementia care, support and services. Dementia. 2012;11(4):427–52. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howrey BT, Thompson BL, Borkan J, et al. Partnering with patients, families, and communities. Fam Med. 2015. September;47(8):604–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen DCR, Kirshenbaum DS, Yan J, Kirshenbaum E, Aseltine RH. Characterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical school. Med Teach. 2012;34(4):305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011. August;86(8):996–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward J, Cody J, Schaal M, Hojat M. The empathy enigma: an empirical study of decline in empathy among undergraduate nursing students. J Prof Nurs. 2012. Jan-Feb;28(1):34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Acad Med. 2014. March;89(3):443–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mealer M, Burnham EL, Goode CJ, Rothbaum B, Moss M. The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(12):1118–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mealer M, Jones J, Moss M. A qualitative study of resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder in United States ICU nurses. Intensive Care Med. 2012. September;38(9):1445–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knowles P. Collaborative communication between psychologists and primary care providers. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009. March;16(1):72–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duffy TP. The Flexner Report–100 years later. Yale J Biol Med. 2011. September;84(3):269–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rothman SM. Health advocacy organizations and evidence-based medicine. JAMA. 2011;305(24):2569–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lawrence K, McWhinnie D, Goodwin A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of laparoscopic versus open repair of inguinal hernia: early results. BMJ. 1995;311(7011):981–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lawrence K, McWhinnie D, Jenkinson C, Coulter A. Quality of life in patients undergoing inguinal hernia repair. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1997. January;79(1):40–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010. June;25(6):601–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jaén CR, Ferrer RL, Miller WL, et al. Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home National Demonstration Project. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8 Suppl 1:S57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller WL. Patient-centered medical home (PCMH) recognition: a time for promoting innovation, not measuring standards. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014. May-Jun;27(3):309–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olthof M, Stevens M, Bulstra SK, van den Akker-Scheek I. The association between comorbidity and length of hospital stay and costs in total hip arthroplasty patients: a systematic review. J Arthroplasty. 2014. May;29(5):1009–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thombs BD, Singh VA, Halonen J, Diallo A, Milner SM. The effects of preexisting medical comorbidities on mortality and length of hospital stay in acute burn injury: evidence from a national sample of 31,338 adult patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245(4):629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Foraker RE, Rose KM, Chang PP, Suchindran CM, McNeill AM, Rosamond WD. Hospital length of stay for incident heart failure: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort: 1987-2005. J Healthc Qual. 2014. Jan-Feb;36(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fleming M, Waterman S, Dunne J, D'Alleyrand J-C, Andersen RC. Dismounted complex blast injuries: patterns of injuries and resource utilization associated with the multiple extremity amputee. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2012. Spring;21(1):32–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Devisch R. Of divinatory connaissance in South-Saharan Africa: The bodiliness of perception, inter-subjectivity and inter-world resonance. Anthropol Med. 2012. April;19(1):107–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Best A, Greenhalgh T, Lewis S, Saul JE, Carroll S, Bitz J. Large-system transformation in health care: a realist review. Milbank Q. 2012. September;90(3):421–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nadler A. Intergroup reconciliation: definitions, processes, and future directions. Tropp LR, editor. The Oxford handbook of intergroup conflict. England: Oxford University Press; 2012:291–308. [Google Scholar]

- 67.IECEP. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Drago-Severson E. Becoming adult learners: principles and practices for effective development. New York: Teachers College Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schon DA. The reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Harper Collins; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mezirow J. Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen I, Forbes C. Reflective writing and its impact on empathy in medical education: systematic review. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2014. August 16;11:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ogur B, Hirsh D. Learning through longitudinal patient care-narratives from the Harvard Medical School-Cambridge Integrated Clerkship. Acad Med. 2009. July;84(7):844–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ogur B, Hirsh D, Krupat E, Bor D. The Harvard Medical School-Cambridge integrated clerkship: an innovative model of clinical education. Acad Med. 2007;82(4):397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hirsh D, Gaufberg E, Ogur B, et al. Educational outcomes of the Harvard Medical School-Cambridge integrated clerkship: a way forward for medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87(5):643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]