Abstract

Background

Cytokines play an important role in tumor angiogenesis and inflammation. There is evidence in the literature that high doses of ascorbate can reduce inflammatory cytokine levels in cancer patients. The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of treatment by intravenous vitamin C (IVC) on cytokines and tumor markers.

Material/Methods

With the availability of protein array kits allowing assessment of many cytokines in a single sample, we measured 174 cytokines and additional 54 proteins and tumor markers in 12 cancer patients before and after a series of IVC treatments.

Results

Presented results show for our 12 patients the effect of treatment resulted in normalization of many cytokine levels. Cytokines that were most consistently elevated prior to treatments included M-CSF-R, Leptin, EGF, FGF-6, TNF-α, β, TARC, MCP-1,4, MIP, IL-4, 10, IL-4, and TGF-β. Cytokine levels tended to decrease during the course of treatment. These include mitogens (EGF, Fit-3 ligand, HGF, IGF-1, IL-21R) and chemo-attractants (CTAC, Eotaxin, E-selectin, Lymphotactin, MIP-1, MCP-1, TARC, SDF-1), as well as inflammation and angiogenesis factors (FGF-6, IL-1β, TGF-1).

Conclusions

We are able to show that average z-scores for several inflammatory and angiogenesis promoting cytokines are positive, indicating that they are higher than averages for healthy controls, and that their levels decreased over the course of treatment. In addition, serum concentrations of tumor markers decreased during the time period of IVC treatment and there were reductions in cMyc and Ras, 2 proteins implicated in being upregulated in cancer.

MeSH Keywords: Allergy and Immunology, Antineoplastic Agents, Ascorbic Acid

Background

Cells produce cytokines in response to a variety of stresses, including infection, physical trauma, and carcinogen-induced injury. Cytokines stimulate a coordinated host response aimed at tissue protection and healing. However, failure of the body to resolve an injury can lead to persistent cytokine production and tissue damage. Chronic cytokine production with angiogenesis and inflammation during tumor growth is an example of this. Cancer cells release various cytokines and growth factors into their surroundings, recruiting and reprogramming other cell types in order to establish a tumor microenvironment [1–11]. Tumor derived cytokines, such as Fas ligand, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and transforming growth factors α and β (TGF), may facilitate the suppression of immune response to tumors [12,13]. The complex interactions between tumor cells and various other cell types, such as endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and leukocytes, involve cascades of cytokines and growth factors that in turn can have local and systemic effects [1–9]. Cytokines such as interleukins 4, 6, 8, and 10 (IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10) along with TGF and VEGF, may regulate tumor growth, promote angiogenesis, induce (or inhibit) inflammation, or modify the antitumor immune responses [6–11]. Some cancer patients exhibit chronic low-grade inflammation that in turn can give rise to fatigue, depression, anorexia, cachexia, pain, and poor prognosis [14,15]. This chronic inflammation is associated with elevated cytokine levels observed in cancer patients. Interleukins 1, 6, 8, 12, and 13 (IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-13), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), monocytes chemoattractant proteins (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory proteins (MIP-1 α, β), interferon α (IFN-α), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), epidermal growth factor (EGF), VEGF, and TNF receptor II have all been reported to be elevated in cancer patient serum relative to that of healthy subjects [1–11].

Recent studies suggest that ascorbate (ascorbic acid, vitamin C) therapy may reduce inflammation and angiogenesis in tumors [16,17].

Intravenous ascorbate therapy is of interest as a potential adjuvant therapy, in part because of the potential for ascorbate, at sufficient concentrations, to inhibit cancer cell growth while serving as a biological response modifier. Ascorbate, at concentrations attainable via intravenous infusions, has been shown to induce apoptosis in cancer cells [18], inhibit tubule formation and angiogenesis [17], stimulate collagen synthesis [19,20], and reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [21]. Ascorbate may protect against activation of HIF-1 [22], an inflammation promoter that is upregulated in tumors [23] and leads to increased production of the angiogenesis factor VEGF. It also may inhibit the activation of NF-κB, a transcription factor that leads to an overexpression of inflammatory proteins and cytokines such as IL-2IL-1β and TNF-α [24–28]. Vitamin C may also inhibit inflammation by blocking the inflammatory activity of GM-CSF, a cytokine that induces an increase in reactive oxygen species in response to tumor necrosis factor and IL-1 [29]. The effects of ascorbate on inflammatory cytokines is concentration dependent, in that doses typical of oral supplementation (250 to 3000 mg per day) do not show any effect [30–35]. Hence, any anti-inflammatory effect of vitamin C is likely confined to situations where the antioxidant is administered intravenously. Ascorbate may also be important in supporting immune function, in part through its antioxidant protection of immune cells [36] and its effects on phosphatase activity, transcription factors, and gene expression [37]. In vitro, T-cell maturation has been shown to depend on vitamin C [38]. Ascorbate may increase phagocytic activity [39] and have anti-proliferative activity comparable to that of IFN-α [40].

Given the role of cytokines in cancer, and the potential ability of ascorbate to modulate cytokine production, we undertook to measure cytokine production in cancer patients before and after treatment with intravenously administered vitamin C.

The goal of the study was to demonstrate that ascorbate therapy may alter cytokine expression in cancer patients in a way that is favorable to tumor suppression.

The present manuscript describes measurements of over 170 cytokines in twelve patients with a variety of cancers. In a separate sample of 4 patients, we assayed a panel of over fifty proteins and cancer markers.

Material and Methods

Serum cytokine and protein analysis

Serum samples from twelve cancer patients and 8 healthy volunteers were obtained for analysis on a voluntary basis with full HIPAA compliance. The research was in compliance of the declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Riordan Clinic. All participants have provided their written informed consent. The serum concentrations of 174 cytokines were determined. Information about the cancer patients is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Information about patients: disease state, type of cancer and previous treatments.

| Patient | Stage (grade) | Classification | Primary cancer | Metastasis | Chemo/radiation | Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 4(4) | T2 N1 M1 | Peripheral nerve sheath sarcoma | Lungs | Yes | Yes |

| C2 | 4(3) | T3 N2 M1 | Colon | Lungs, Brain | Yes | Yes |

| C3 | 4(1) | T3-4 N2 M1 | Lung | Brain | Yes | Yes |

| C4 | 3(3) | T3 N3 M1 | Breast | Brain | Yes | Yes |

| C5 | Renal | Pancreas | Yes | |||

| C6 | 4(3) | T3 N2 M1 | Ovarian | Lungs | Yes | Yes |

| C7 | 1 | Breast | No | No | ||

| C8 | 3(3) | T3 N1 M0 | Pancreas | No | No | |

| C9 | 2 | T1 N1 M0 | Breast | Invasive | Yes | Yes |

| C10 | 4(1) | T1N1M1 | Breast | Lung, liver, bone marrow, brain | ||

| C11 | 2(3) | T1 N1 M0 | Prostate | Bone | Yes | |

| C12 | 3(4) | T4-3 N1 M0 | Colon | Invasive | Yes | Yes |

Most patients were late stage, had metastatic disease, and had previously undergone surgery and/or conventional therapy. Cancer patients were treated with intravenous ascorbate infusions at the Riordan Clinic according to the Riordan IVC protocol. The details of this protocol have been described elsewhere [41] and are available for download at the Riordan Clinic web site: https://riordanclinic.org/research-study/vitamin-c-research-ivc-protocol/. Briefly, new cancer patients are given a 15-gram injection for their first dose, followed by a 25-gram injection the next day. Dosage is then adjusted by the physician based on the patients’ tolerance and plasma ascorbate levels attained post infusion. Patients in the present study reached 50 grams per infusion by their sixth course of treatment. Serum samples for cytokine analysis were taken before the onset of each patient’s first IVC treatment and after the patient’s sixth IVC treatment. Vitamin C concentrations in plasma immediately after infusions were monitored using standard protocols [40].

Serum concentrations of 174 cytokines were measured using a protein array kit (AAH-CYT-2000, RayBiotech). The assay was conducted according to the manufacture’s provided procedure. In this assay, antibodies to 174 cytokines are bound to a membrane support. After a sample is added and cytokines are allowed to bind to antibodies, additional antibodies tagged with chemiluminescent markers are added. The chemiluminescent signal was imaged by the BioImage system (Alpha Innotech). The antigen-antibody spots on the image were circled by Spot Denso of FluorChem SP software (Alpha Innotech). Serum samples from 8 healthy volunteers were used to establish normal ranges. Specifically the mean χ̄ and standard deviation sd were determined for each cytokine, with a ±2 SD range being considered “normal”. Z-scores for each cytokine in each cancer patient were computed:

Furthermore, cytokines were also scored based on their ability to promote (+) or inhibit (−) angiogenesis or inflammation. An angiogenesis score and an inflammation score were then computed for each sample by taking the sum of the z-scores for angiogenesis (or inflammation) promotors and subtracting out the z-scores of the angiogenesis (or inflammation) inhibitors. The result was then divided by the total number of cytokines included in the sum.

Further tests were done on 4 of 12 cancer patients for IVC influences as measured by protein array assay. Serum concentrations of 58 proteins (a list is provided along with results in Table 2) were measured by array, which is a label-based assay (with antibody spotted and analyte labeled) for 58 markers of cytokines and oncoproteins based on the principle of Ray Biotech protein array kit (#AAH-BLM-1-2) and modified.

Table 2.

This table shows data for all of fifty-eight proteins measured in four patients: mean initial (I) and final (F) z-scores, and change in mean z-score (Δ).

| I | F | Δ | I | F | Δ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFP | −0.12 | 0.24 | 0.36 | LEDGF | −0.83 | −0.21 | 0.62 |

| ALK | −0.99 | 0.24 | 1.23 | MAGE-A1 | −0.64 | −0.16 | 0.47 |

| Bcl-2 | −0.51 | −0.24 | 0.26 | MMP-3/10 | −1.06 | 0.01 | 1.06 |

| BRCA1 | −0.83 | −0.05 | 0.78 | NSE | −0.41 | −0.27 | 0.14 |

| BRCA2 | −0.91 | 0.18 | 1.10 | NY-ESO-1,2 | −0.46 | 0.18 | 0.64 |

| b-Catenin | −0.36 | 0.28 | 0.64 | Oct-3/4 | −1.11 | −0.16 | 0.94 |

| CA 125 | −0.59 | −0.08 | 0.51 | P21 | −0.84 | 0.31 | 1.15 |

| CA 15-3 | 7.29 | 1.58 | −5.71 | P53 | 0.09 | −0.25 | −0.34 |

| CA 19-9 | 10.49 | 0.36 | −10.13 | P63 | −1.06 | −0.02 | 1.04 |

| Caspase-8 | 0.11 | −0.24 | −0.35 | PSA, A67 | −0.80 | 0.30 | 1.10 |

| CD105 | −0.47 | 0.10 | 0.56 | PSP94 | −0.37 | 0.14 | 0.51 |

| CD34 | −0.79 | −0.42 | 0.36 | Ras, pan | 1.18 | −0.09 | −1.27 |

| CDK2 | −1.03 | 0.20 | 1.24 | SCCA1,2 | 0.07 | −0.29 | −0.35 |

| CEA, pan H-8 | 5.37 | 0.09 | −5.28 | SCF | −0.95 | −0.10 | 0.85 |

| CgA | −1.34 | −0.46 | 0.89 | Sel-1L | −0.65 | 0.31 | 0.96 |

| c-Jun | −1.21 | −0.38 | 0.83 | Sox-2 | −0.46 | −0.09 | 0.37 |

| CK, Pan | −0.57 | −0.16 | 0.41 | SSEA-1 | −0.42 | 0.41 | 0.84 |

| c-Myc | 10.90 | 0.75 | −10.15 | CA242 | 11.92 | 0.15 | −11.77 |

| Cox-2 | −0.73 | −0.53 | 0.20 | h-IgG | −2.03 | 1.74 | 3.77 |

| Fas | −0.82 | 0.19 | 1.02 | Survivin | −0.68 | −0.50 | 0.18 |

| Ferritin | −0.56 | 0.25 | 0.80 | TATI | −0.51 | −0.18 | 0.33 |

| HCG | −0.52 | 0.12 | 0.64 | TERT | −0.63 | −0.23 | 0.40 |

| Her-2 | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.01 | TGF-β1,2,3 | −0.23 | 0.02 | 0.26 |

| HSP70 | 0.36 | −0.16 | −0.51 | TIMP-1 | −0.33 | 0.13 | 0.46 |

| HSP90 | −0.76 | 0.20 | 0.96 | TRA-1-60 | −1.12 | −0.14 | 0.98 |

| IGF-II | −0.96 | −0.39 | 0.57 | Tyrosinase | −0.72 | −0.30 | 0.43 |

| IGF-IR | −0.83 | −0.07 | 0.76 | uPA | −0.53 | 0.20 | 0.72 |

| IL-10 | −0.66 | −0.40 | 0.26 | CRP | −0.75 | −0.03 | 0.72 |

| IL-2 | −0.68 | −0.21 | 0.47 | h-albumin | 8.20 | 2.40 | −5.80 |

Serum samples from 8 healthy volunteers (35–60 years old, 4 males and 4 females) were used to establish normal ranges, and z-scores for each protein in each cancer patient were computed as described above.

Vitamin C in serum of subjects was measured by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by Systat software (Systat, Inc.) and Kaleidagraph software. Graphs and curve fits were generated by Kalaidagraph (Synergy Software) and tests of significance were carried out using Mann-Whitney non-parametric test. Variables were presented as mean values ± SD. Statistical significance was accepted if the null hypothesis could be rejected at p≤0.05.

Results

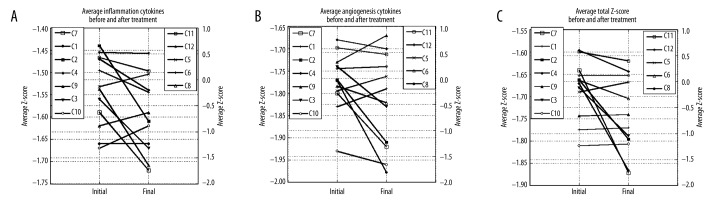

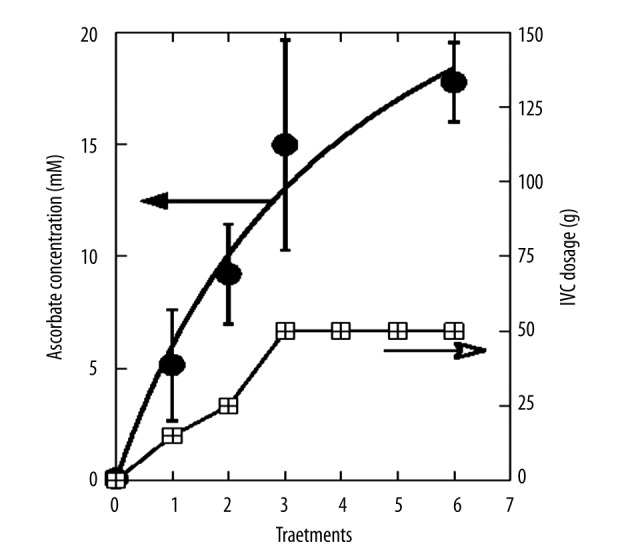

The serum concentrations of 174 cytokines were determined in each of 12 cancer patients before and after a course of intravenous vitamin C therapy. Plasma ascorbate levels, shown in Figure 1, ranging from 5 mM to 15 mM, were achieved immediately after infusions, consistent with previous observations with the Riordan protocol [41]. Patients were treated during 2 weeks by 6 IVC infusions.

Figure 1.

Plasma vitamin C concentrations (mM) immediately after IVC infusions (circles), for a typical dosing regimen (dose given by boxes) under the Riordan Protocol. Values are averages for twelve cancer patents used in the cytokine study. Curve fit is carried out using the Michaelis-Menton equation.

The information on the 12 cancer patients is given in Table 1. Our patients varied considerably in type of cancer, prognosis, and treatment. Total treatment times ranged from less than 1 month to 52 months, with cancers of the breast, prostate, colon, lung, sarcoma, and pancreas all represented. Data presented in article were measured at the beginning of patient enrollment during first 2 weeks.

The comparison of initial samples (prior to therapy) and final samples (after the last of 6 IVC treatments) showed important changes in cytokine levels. Cytokines that moved in the normal range and those that moved outside the normal range are listed in Table 3. The values presented in 2 columns for each patient show the cytokines that were out of normal range (NR ±2SD) and returned to normal range or were in normal range and decreased or increased to levels lower or higher than NR. Values are given in the percentage of difference after treatment to pretreatment levels.

Table 3.

Changes in cytokines that moved to normal range (NR ±2SD) or were in normal range and decreased (−) or increased (+) to levels lower or higher than NR. Values are given in the percentage of difference post treatment to pretreatment levels.

| % change (out of NR to NR) | % of change (in NR – out of NR) | % change (out NR – in RR) | % of change (in NR – out NR) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast ca (C7) | −67 | Ovarian ca (C6) | 37 | ||

| dtk | −31 | BDNF | |||

| ENA-78 | −21 | BMP-4 | −33 | ||

| Fas/TNFRSF6 | −46 | ENA-78 | −65 | ||

| FGF-4 | −69 | Flt-3 Ligand | −53 | ||

| IL12-p40 | −70 | IL-4 | −58 | ||

| IL-2 Ra | −57 | IL-5 Ra | 31 | ||

| IL-6 R | −64 | LIGHT | −49 | ||

| Leptin | −75 | MDC | −33 | ||

| sTNF RII | TNF-alpha | −32 | |||

| prostate ca (C11) | Pancreatic ca (C8) | ||||

| IGFBP-4 | −31 | ENA-78 | −57 | ||

| IL-1 R II | 44 | −58 | Endoglin | −76 | |

| IL-1 R4/ST2 | GITR ligand | −80 | |||

| IL-1alpha | −36 | MIP-1-alpha | −54 | ||

| Lymphotactin | −47 | TARC | −59 | ||

| MIF | −29 | TIMP-1 | −51 | ||

| MIP-1-beta | −41 | 31 | TIMP-2 | −77 | |

| MPIF-1 | TPO | −76 | |||

| Osteoprotegerin | −72 | 44 | uPAR | −66 | |

| TGF-beta 3 | VEGF | −86 | |||

| Colon ca (C11) | 40 | Renal ca (C5) | |||

| BMP-6 | Activin A | −53 | |||

| Eotaxin | −31 | 37 | BMP-6 | −44 | |

| GDNF | GCP-2 | −37 | |||

| IFN-gamma | −34 | Leptin R | 40 | ||

| IGF-I SR | −33 | MIP-1-delta | −33 | ||

| IL-2 Ra | 57 | sTNF RII | 43 | ||

| Lymphotactin | −44 | −54 | TGF-beta 1 | 38 | |

| M-CSF | 55 | Tie-1 | −31 | ||

| MIP-3-beta | 60 | Tie-2 | 38 | ||

| TPO | 73 | Sarcoma (C1) | |||

| TRAIL-R3 | DR6 (TNFRSF21) | −45 | |||

| Eotaxin-3 | 28 | ||||

| IL-1 RI | 32 | ||||

| IL-3 | 37 | ||||

| NAP-2 | −74 | ||||

| sTNF RII | 45 |

Generally, patients with elevated cytokines initially showed the most dramatic changes over time. The overall effect of treatment was to decrease most cytokine levels; whether this is due to the ascorbate treatments or simply due to disease progression is not known, since we did not have untreated control subjects in this study, but as the period of treatment was 2 weeks, we suggest that all changes were due to treatment.

There are several cytokines for which a variety of patients saw decreases after IVC therapy. These include mitogens (EGF, Fit-3 ligand, HGF, IGF-1, IL-21R) and chemo-attractants (CTAC, Eotaxin, E-selectin, Lymphotactin, MIP-1, MCP-1, TARC, SDF-1), as well as inflammation and angiogenesis factors (FGF-6, IL-1, TGF-1).

Several improved cytokines were common for several cancer patients. The cytokines that were increased after treatments were TIMP (high concentrations are associated with good prognosis in patients with breast cancer), Beta-NGF (stimulates chemotactic recruitment of leukocytes), I-TAC (potent chemoattractant for IL-2 activated T cells), IL-1R (antagonistic to IL-1, a non-signaling decoy receptor, which functions by capturing IL-1 and blocking IL-1R1), and Il-3 (enhances tumor antigen presentation).

Several cytokines were decreased: MIP-1 (causes local inflammatory response, chemoattractant for T cells and monocytes), IL-10 (inhibits antigen-presenting cells, inhibits cytokine production), Lymphotactin (enhances T cell recruitment), IL-1 (co-stimulates cell activation, inflammation, required for tumor invasion and angiogenesis), BMP (regulates cellular proliferation and apoptosis), and IGF (promotes the proliferation of many types of cells).

The cytokine profile in these patients was compared to the normal range (determined from 8 healthy volunteers). We calculated for each patient the percentage of cytokines (from all measured cytokines) that were in normal range before and after treatment, percentage of cytokines that returned to normal range and percentage of cytokines that remained higher or lower than normal range. The cytokines that remained in normal range before and after treatment were in a range of 60–80%, the improved cytokines ranged from 1% to 9%, with lowest value for the lung cancer patient, and the levels of 7–9% for patients with prostate, colon, renal, and ovarian cancers. The cytokines that were not changed and were outside the normal levels ranged from 3% to 23%.

There is quite a contrast, with 7 patients (all breast cancer patients, sarcoma, lung and colon cancer) having cytokine levels that are predominately below the normal range while 5 others (prostate, ovarian, pancreas, renal and colon cancers) had cytokine levels that were predominantly in the normal range. Interestingly, all 4 of the breast cancer patients in our study fell into the first group, showing depressed cytokine levels across the board. Only 28 cytokines had average z-scores (mean of twelve patients) above zero, with BMP-4, SDF-1, IL-1alpha, MCP-2 and LIGHT having the highest average z-scores before treatment.

Among the cytokines considered relevant to inflammation and angiogenesis, the ones with positive mean (for the twelve cancer patients) z-scores are FGF-4 (0.33), SCF (z̄=0.1), MIP-3-alpha (z̄=0.2), IL-9 (z̄=0.24), BMP-6 (z̄=0.54), TGF-beta 3 (z̄=0.78), CK beta (z̄=1.2), IL-1alpha (z̄=1.8), MIF (z̄=1.04), and MIP-1-delta (z̄=1.1). All of these cytokines, it should be noticed, decreased in concentration over the course of IVC therapy.

In an attempt to understand how these changes might affect cancer, we separated the angiogenesis factors and inflammation factors. Angiogenesis and inflammation scores for each patient, computed as described above, are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The table shows average score for angiogenesis and inflammation cytokine scores and change in mean z-score (Δ).

| Patient | Angiogenesis score | Inflammation score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | Δ | p-one tail | Initial | Final | Δ | p-one tail | |

| C1 (sarcoma) | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.4 | −1.66 | −1.66 | 0.00 | 0.2 |

| C2 (colon ca) | −0.04 | −0.24 | −0.20 | 0.2 | −1.44 | −1.61 | −0.17 | 0.0 |

| C3 (lung ca) | −0.10 | −0.14 | −0.04 | 0.3 | −1.56 | −1.67 | −0.11 | 0.4 |

| C4 (breast ca) | 0.01 | −0.17 | −0.18 | 0.4 | −1.47 | −1.54 | −0.08 | 0.2 |

| C5 (renal ca) | −0.37 | −0.11 | 0.26 | 0.1 | −0.13 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.5 |

| C6 (ovarian ca) | −0.67 | −0.81 | −0.14 | 0.0 | 0.18 | −0.24 | −0.43 | 0.5 |

| C7 (breast ca) | 0.20 | 0.10 | −0.10 | 0.2 | −1.59 | −1.72 | −0.12 | 0.0 |

| C8 (pancreatic ca) | 0.21 | −0.43 | −0.65 | 0.0 | −0.18 | −1.65 | −1.47 | 0.1 |

| C9 (breast ca) | −0.17 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.4 | −1.62 | −1.59 | 0.02 | 0.4 |

| C10 (breast ca) | −0.21 | −0.28 | −0.07 | 0.4 | −1.67 | −1.62 | 0.05 | 0.3 |

| C11 (prostate) | −0.76 | −0.89 | −0.14 | 0.3 | 0.43 | 0.17 | −0.26 | 0.4 |

| C12 (colon ca) | −0.51 | −0.62 | −0.11 | 0.5 | 0.53 | 0.51 | −0.02 | 0.2 |

Table 5 shows cytokines from those categories that showed the most change over the course of treatment.

Table 5.

This table shows data for angiogenesis and inflammation cytokine that showed the most change, or were changed in the most patients, during treatment: mean initial (I) and final (F) z-scores, change in mean z-score (Δ). Indication of which cytokines are angiogenesis (Ag) or inflammation (If) factors are given.

| Ang | Inf | I | F | Δ | Ang | Inf | I | F | Δ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activin A | If | −1.31 | −1.58 | 0.28 | BMP-6 | Ag | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.37 | ||

| Angiogenin | Ag | −1.00 | −1.12 | 0.12 | CK beta 8-1 | Ag | 1.20 | 0.79 | 0.41 | ||

| DR6 (TNFRSF21) | If | −0.95 | −1.10 | 0.15 | Endoglin | Ag | If | −1.10 | −1.84 | 0.74 | |

| EGF | Ag | −1.43 | −1.63 | 0.19 | Eotaxin | If | −0.57 | −1.21 | 0.64 | ||

| Eotaxin-2 | If | −0.74 | −0.85 | 0.11 | Fas-Ligand | If | −1.23 | −1.70 | 0.47 | ||

| FGF-4 | Ag | 0.33 | 0.07 | 0.27 | FGF-7 | Ag | If | −0.17 | −0.54 | 0.37 | |

| FGF-6 | Ag | −1.43 | −1.63 | 0.19 | Fractalkine | If | −1.86 | −2.21 | 0.35 | ||

| GM-CSF | Ag | If | −0.90 | −1.12 | 0.22 | HGF | Ag | −0.95 | −1.27 | 0.32 | |

| IFN-gamma | Ag | If | −0.08 | −0.33 | 0.25 | I-309 | Ag | If | −0.32 | −0.66 | 0.34 |

| IL-1 R II | If | −1.07 | −1.32 | 0.25 | IL-1 R4/ST2 | Ag? | If | −0.33 | −0.98 | 0.65 | |

| IL-1 RI | If | −1.67 | −1.78 | 0.11 | IL-10 | Ag | If | −0.79 | −1.25 | 0.46 | |

| IL12-p40 | If | −1.37 | −1.53 | 0.16 | IL-18 BPa | If | −0.64 | −1.06 | 0.42 | ||

| IL-15 | Ag | If | −0.34 | −0.55 | 0.21 | IL-1beta | Ag | If | −0.67 | −1.46 | 0.79 |

| IL-1alpha | Ag | If | 1.84 | 1.71 | 0.13 | IL-4 | If | −1.21 | −1.73 | 0.53 | |

| IL-1ra | If | −0.13 | −0.43 | 0.31 | Lymphotactin | If | −0.27 | −0.59 | 0.32 | ||

| IL-2 | Ag | If | −1.06 | −1.33 | 0.28 | MIF | If | 1.04 | 0.39 | 0.65 | |

| IL8 | If | −0.74 | −0.91 | 0.17 | MIG | Ag | If | −1.21 | −1.56 | 0.34 | |

| IL-9 | Ag | If | 0.24 | −0.02 | 0.26 | MIP-1-beta | If | 0.22 | −0.36 | 0.58 | |

| LAP | Ag | −0.82 | −1.10 | 0.27 | MIP-3-alpha | Ag | If | 0.19 | −0.28 | 0.48 | |

| MCP-1 | If | 0.20 | −0.59 | 0.79 | MMP-1 | Ag | −0.25 | −0.59 | 0.34 | ||

| MCP-3 | If | −0.43 | −0.62 | 0.19 | MMP-9 | Ag | −0.94 | −1.30 | 0.36 | ||

| MCP-4 | Ag | If | −1.04 | −1.22 | 0.18 | Osteoprotegerin | If | −1.18 | −1.76 | 0.58 | |

| MIP-1-alpha | If | −1.58 | −1.72 | 0.15 | PDGF Rb | Ag | −1.47 | −1.85 | 0.39 | ||

| MIP-1-delta | If | 1.13 | 0.30 | 0.83 | Prolactin | Ag | If | −0.64 | −1.11 | 0.47 |

Some, such as DR6, IL-1α, IL1-R1, and IL-12, showed considerable variability without consistent trends, while others showed more consistent decreases over time. Particularly striking were decreases in the angiogenesis factors endoglin, EGF, and FGF-6. Inflammation factors (or anti-inflammation factors) that decreased most dramatically were eotaxin, IL-4, IL-10, lymphotactin, MCP-1, MIP-1β, TARC, TGF-β3, and TGF-β1. There does not appear to be any systematic decrease in pro-inflammatory agents versus anti-inflammatory agents.

Overall, the inflammation and angiogenesis scores decreased, suggesting that over time the cytokine mix for these patients’ moves toward a less inflammatory and less angiogenic state. These trends are shown graphically in Figure 2A–2C. The declines in values are more dramatic in subjects who started with positive initial values. The changes in z-scores, angiogenesis scores, and inflammation scores were especially dramatic for the pancreatic cancer patient, a subject who showed cytokine profiles characterized by normal to elevated levels before treatment, and reduced levels after treatment. This patient was interesting in that he did not undergo radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or surgery.

Figure 2.

(A–C) Average z-scores, angiogenesis scores, and inflammation scores for twelve cancer patients before (I) and after (F) IVC therapy are plotted.

Three of these 12 patients had positive results with IVC therapy. Prostate patient had proved refractory to standard treatment and was given a prognosis of death within 1 year; with IVC treatments he survived for 6 years. The sarcoma patient began IVC therapy after undergoing radiation and chemotherapy with poor prognosis. She was treated for 3 years, at which point scans showed her to be clear of almost all metastases. Finally, the breast cancer patient (who had an invasive tumor with a recurrence score of 23) was treated with IVC after mastectomy. She was treated at the Riordan clinic for 2.5 years before moving to another location. Examining data in Tables 3 and 5, we do not see much commonality between these 3 subjects. Patients with breast cancer and sarcoma had cytokine levels what were reduced during treatment, with large reductions in angiogenesis and inflammation scores. The patient with prostate cancer, however, showed profiles with reduced cytokine levels and did not show much change in levels during treatment.

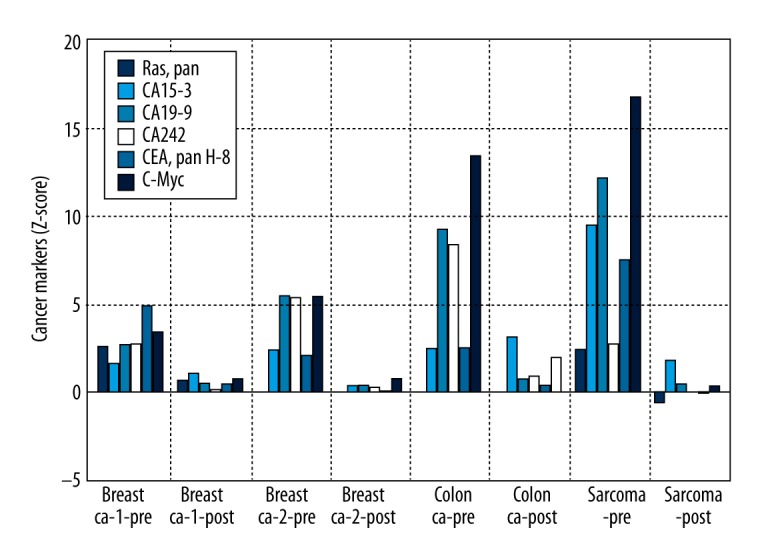

To gain a different perspective, and perhaps narrow the focus a bit, we tested 4 of the 12 cancer patients for serum levels of 58 protein markers. We chose the patient with sarcoma, who came after radiation and chemotherapy with very poor prognosis; 2 patients with breast cancer (both after mastectomy, but 1 of them had metastasis and treated by chemotherapy and radiation and another did not have metastasis and chemotherapy); and the patient with colon cancer after conventional treatment (surgery and chemotherapy). As indicated, these patients were subject to a series of 6 intravenous vitamin C treatments prior to the final assay. The results for 4 patients of protein profiles and their average z-scores are listed in Table 2.

Before treatment, all measured proteins except CEA pan H-8, CA 15-3, h-albumin, CA 19-9, c-Myc and CA242 were in normal range ±2SD. The most dramatic and consistent results involved decreases in values of several tumor markers (CA 15-3, CA 19-9, CEA, and CA 242) as well as decreases in the transcription regulator c-Myc. The gene responsible for producing this protein is thought to be mutated in cancer cells, leading to increased expression and increased cell proliferation. Decreases seen in these markers during treatments are therefore encouraging. Figure 3 shows a histogram to indicate how dramatically these tumor markers decreased over the course of treatment.

Figure 3.

Column plot for tumor markers in each of 4 cancer patients before and after 7 IVC treatment sessions.

For the average Z-score of Ras protein, we saw a return from an overproduced state (Z=1.18) to normal ranges (Z=−0.08). Other encouraging results include statistically significant increases in BRCA1 and BRCA2, both DNA repair agents key in cell cycle control, and c-Jun, an important factor in cell differentiation, proliferation control, and apoptosis. However, MMP-3/10, a matrix metalloproteinase that is critical in maintaining extracellular matrix composition, increased slightly during treatments.

In summary, the protein assay test shows several tumor markers being reduced or restored to normal ranges over the course of treatments.

Discussion

We are able to show that average z-scores for several inflammatory and angiogenesis promoting cytokines are positive, indicating that they are higher than averages for healthy controls, and that their levels decreased over the course of treatment. Some of these results confirm previous reports, including EGF, FGF, MIP, MCP, and TNF. Others elevated in our study, including IL-4, 10, MCSF-R, and Leptin, have not been reported previously as being elevated. Of the cytokines that are thought to be important in angiogenesis and inflammation, we saw dramatic decreases in EGF, FGF, IL-4, IL-10, lymphotactin, MCP-1, MIP, TARC, TGF-α, and TGF-β. We computed 2 parameters, the angiogenesis score and the inflammation score, to provide an ‘average’ z-score for cytokines involved in these processes. These scores decreased noticeably during the period of treatments, with changes being more dramatic in the cancer patients, who had elevated levels of inflammatory and angiogenic cytokines prior to treatment. Our small sample size did not allow us to demonstrate differences pre-versus post-treatment with 95% confidence, but we did have significance near the α=0.10 level in some cases, suggesting that further measurements may be worthwhile.

Our encouraging finding may be the measurements of 58 proteins and markers in 4 cancer patients. We found that serum concentrations of tumor markers decreased during the time period of IVC treatment. In addition to the marker decreases, we saw reductions in c-Myc and Ras, 2 proteins implicated in being upregulated in cancer. We also saw increases in some proteins that might be considered beneficial in combating cancer, including c-Jun, which plays a role in differentiation and apoptosis, and the DNA repair agents BRCA1 and 2. It should be noted that changes that occurred during the course of therapy (1 or 2 weeks) may be due to the therapy itself; however, there were no untreated controls for cancer patients in this study.

The use of high-dose intravenous vitamin C as a possible therapy for cancer has been revisited recently [41–48] and several trails of the use of IVC as adjuvant therapy are under way. In our study we analyzed cytokines as the messengers for the regulation of the inflammatory and angiogenic cascades. Our data confirm the inhibition and positive regulation of the part of cytokines responsible for angiogenesis and inflammation after 6 IVC treatments.

Angiogenesis and inflammation share common pathways, and both play key roles in the initiation and progression of cancer. Inflammatory cells may facilitate angiogenesis and promote tumor cell growth, invasion, and metastasis. The FDA has approved several angiogenesis inhibitors for anticancer therapy. While these drugs seem to have mild adverse effects, recent studies reveal the potential for complications that reflect the importance of angiogenesis in normal body processes. Research is also under way to develop pharmaceuticals that reduce inflammation. High-dose ascorbic acid therapy may also be a useful strategy for reducing inflammation and angiogenesis. Phase I studies show high-dose (10 to 100 grams) intravenous ascorbate therapy shows a good safety profile [45,49–53] while improving quality of life as measured by cancer patient reported scores in physical, emotional, and cognitive function. Patients also show reduced fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, and appetite loss after IVC administration.

Conclusions

Because intravenous ascorbate therapy is of interest as a potential adjuvant therapy, we analyzed the levels of cytokines before and after high-dose ascorbic acid treatment in cancer patients. The IVC injections resulted in increased concentration of ascorbic acid in blood, from 5 mM after first 15 g IVC infusion to 15 mM after last 50 g IVC. Given the role of cytokines in cancer, and the potential ability of ascorbate to modulate cytokine production, we measured cytokine production in cancer patients before and after treatment. It should be noted that changes that occurred during the time of therapy (2 weeks) may be considered being due to the therapy itself; however, there were no untreated controls of cancer patients in this study. We were able to show that average z-scores for several inflammatory and angiogenesis promoting cytokines that were higher than average for healthy controls decreased over the duration of treatment. In addition, serum concentrations of tumor markers decreased during the period of treatment and there were reductions in c-Myc and Ras proteins thought to be upregulated in cancer.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that vitamin C therapy can downregulate angiogenesis and inflammation promoting cytokines in some cancer patients. Future studies should focus on a larger sample of cancer patients, and perhaps a greater variety of tumor types.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Meng X, Yin Z, Rogers A, and Zhong J for their hard work in improvement of cytokine testing procedure and cytokine measurements.

Footnotes

Source of support: The study was supported in part by the Flossie E West Memorial Trust

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sheu BC, Chang WC, Cheng CY, et al. Cytokine regulation networks in the cancer microenvironment. Bioscience. 2008;13:3152. doi: 10.2741/3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruchard M, Ghiringhelli F. Tumor microenvironment: regulatory cells and immunosuppressive cytokines. Med Sci (Paris) 2014;30:429–35. doi: 10.1051/medsci/20143004018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee S, Margolin K. Cytokines in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers. 2005;3:3856–93. doi: 10.3390/cancers3043856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dranoff G. Cytokines in cancer pathogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:11–21. doi: 10.1038/nrc1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, Inflammation and Cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Simone V, Franzè E, Ronchetti G, et al. Th17-type cytokines, IL-6 and TNF-α synergistically activate STAT3 and NF-κB to promote colorectal cancer cell growth. Oncogene. 2015;34:3493–503. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarhini AA, Lin Y, Zahoor H, Shuai Y, et al. Pro-Inflammatory cytokines predict relapse-free survival after one month of Interferon-α but not observation in intermediate risk melanoma patients. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun X, Ingman WV. Cytokine networks that mediate epithelial cell-macrophage crosstalk in the mammary gland: implications for development and cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2014;19:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s10911-014-9319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gkotzamanidou M, Christoulas D, Souliotis VL, et al. Angiogenic cytokines profile in smoldering multiple myeloma: No difference compared to MGUS but altered compared to symptomatic myeloma. Med Sci Monit. 2013;19:1188–94. doi: 10.12659/MSM.889752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taniguchi K, Karin M. IL-6 and related cytokines as the critical lynchpins between inflammation and cancer. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:54–74. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuyama T, Ichiki Y, Yamada S, et al. Cytokine production of lung cancer cell lines: Correlation between their production and the inflammatory/immunological responses both in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1048–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan-Wan L, Karin M. A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1175–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI31537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim R, Emi M, Tanabe K, Arihiro K. Tumor-driven evolution of immunosuppressive networks during malignant progression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5527–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Argiles JM, Busquets S, Toledo M, et al. The role of cytokines in cancer cachexia. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009;3:263–68. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283311d09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deans C, Wigmore SJ. Systemic inflammation, cachexia and prognosis in patients with cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005;8:265–69. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000165004.93707.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikirova NA, Casciari JJ, Taylor PR, Rogers AM. Effect of high-dose intravenous vitamin C on inflammation in cancer patients. J Transl Med. 2012;10:189. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikirova N, Ichim T, Riordan N. Anti-angiogenic effect of high doses of ascorbic acid. J Transl Med. 2008;6:50. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casciari JJ, Riordan NH, Schmidt TS, et al. Cytotoxicity of ascorbate, lipoic acid, and other antioxidants in hollow fiber in vitro tumors. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1544–50. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qiao H, Bell J, Juliao S, et al. Ascorbic acid uptake and regulation of type I collagen synthesis in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Res. 2009;46:15–24. doi: 10.1159/000135661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsutsumi K, Fujikawa H, Kajikawa T, et al. The role of ascorbic acid on collagen structure and levels of serum interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in experimental lathyrism. J Periodontal Res. 2012;47:263–71. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartel C, Strunk T, Bucsky P, Schultz C. Effects of vitamin C on intracytoplasmic cytokine production in human whole blood monocytes and lymphocytes. Cytokine. 2004;27:101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao P, Zhang H, Dinavahi R, et al. HIF-dependent antitumorigenic effect of antioxidants in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:230–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuiper C, Molenaar IG, Dachs GU, et al. Low ascorbate levels are associated with increased hypoxia-inducible factor-1 activity and an aggressive tumor henotype in endometrial cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5749–58. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cárcamo JM, Pedraza A, Bórquez-Ojeda O, et al. Vitamin C is a kinase inhibitor: dehydroascorbic acid inhibits IkBα kinase β. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6645–52. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6645-6652.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowie AG, O’Neill LAJ. Vitamin C inhibits NF-κB activation by TNF via the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Immunol. 2000;165:7180–88. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pugazhenthi S, Zhang Y, Bouchard R, Mahaffey G. Induction of an inflammatory loop by interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α involves NF-κB and STAT-1 in differentiated human neuroprogenitor cells. Plos One. 2013;8:e69585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang DJ, Ratnam NM, Byrd JC, Guttridge DC. NF-κB functions in tumor initiation by suppressing the surveillance of both innate and adaptive immune cells. Cell Reports. 2014;9:90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Los M, Schenk H, Hexel K, et al. IL-2 gene expression and NF-kappa B activation through CD28 requires reactive oxygen production by 5-lipoxygenase. EMBO J. 1995;14:3731–40. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cárcamo JM, Bórquez-Ojeda O, Golde DW. Vitamin C inhibits granulocyte macrophage – colony-stimulating factor – induced signaling pathways. Blood. 1999;9:3205. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh J, Singh U. Ascorbic acid has superior ex vivo antiproliferative, cell death-inducing and immunomodulatory effects over IFN-a in HTLV-1-associated myelopathy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:525–26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Block G, Jensen C, Dietrich M, et al. Plasma C-reactive protein concentrations in active and passive smokers: influence of antioxidant supplementation. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23:141–47. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Q, Bjorkhem I, Wretlind B, et al. Effect of ascorbic acid on microcirculation in patients with type II diabetes: a randomized placebo-controlled cross-over study. Clin Sci (Lond) 2005;108:507–13. doi: 10.1042/CS20040291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fumeron C, Nguyen-Khoa T, Saltiel C, et al. Effects of oral vitamin C supplementation on oxidative stress and inflammation status in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1874–79. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruunsgaard H, Poulsen HE, Pedersen BK, et al. Long-term combined supplementations with alphatocopherol and vitamin C have no detectable anti-inflammatory effects in healthy men. J Nutr. 2003;133:1170–73. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.4.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antoniades C, Tousoulis D, Tountas C, et al. Vascular endothelium and inflammatory process, in patients with combined type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary atherosclerosis: the effects of vitamin C. Diabetes Med. 2004;21:552–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan Z, Garg SK, Banerjee R. Regulatory T cells interfere with glutathione metabolism in dendritic cells and T cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41525–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.189944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canali R, Natarelli L, Leoni G, et al. Vitamin C supplementation modulates gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells specifically upon an inflammatory stimulus: a pilot study in healthy subjects. Genes Nutr. 2014;9:390–403. doi: 10.1007/s12263-014-0390-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manning J, Mitchell B, Appadurai DA, et al. Vitamin C promotes maturation of T-cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:2054–67. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de-la-Fuente M, Ferrandez MD, Burgos MS, et al. Immune function in aged women is improved by ingestion of vitamin C and E. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;76:373–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moens B, Decanine D, Menezes SM, et al. Ascorbic acid has superior ex vivo antiproliferative, cell death-inducing and immunomodulatory effects over IFN-α in HTLV-1-Associated Myelopathy. PLoS. 2012;6:e1729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riordan HD, Riordan N, Casciari J, et al. The Riordan Intravenous Vitamin C (IVC) Protocol for adjunctive cancer care: IVC as a chemotherapeutic and biological response modifying agent. In: Saul Andrew W., editor. In book: The Orthomolecular Treatment of Chronic Disease. Basic Health publications, INC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma Y, Chapman J, Levine M, et al. High-dose parenteral ascorbate enhanced chemosensitivity of ovarian cancer and reduced toxicity of chemotherapy. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:1–10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeom CH, Lee G, Park J, et al. High dose concentration administration of ascorbic acid inhibits tumor growth in BLAB/C mice implanted with sarcoma 180 cancer cells via the restriction of angiogenesis. J Transl Med. 2009;7:70. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Padayatty SJ, Sun AY, Chen Q, et al. Vitamin C: Intravenous use by complementary and alternative medicine practitioners and adverse effects. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stephenson CM, Levin RD, Spector T, Lis CL. Phase I clinical trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability,and pharmacokinetics of high-dose intravenous ascorbic acid in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;72:139–46. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2179-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson MK, Baguley BC, Wall C, et al. Review of high-dose intravenous vitamin C as an anticancer agent. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10:22–37. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parrow NL, Leshin Jonathan A, Levine M. A reassessment based on pharmacokinetics. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:2141–56. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Padayatty SJ, Levine M. Reevaluation of ascorbate in cancer treatment: emerging evidence, open minds and serendipity. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19:423–25. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffer LJ, Levine M, Assouline S, et al. Phase I clinical trial of i.v. ascorbic acid in advanced malignancy. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1969–74. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monti DA, Mitchell E, Bazzan AJ, et al. Phase I evaluation of intravenous ascorbic acid in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riordan HD, Casciari JJ, Gonzalez MJ, et al. A pilot clinical study of continuous intravenous ascorbate in terminal cancer patients. P R Health Sci J. 2005;24:269–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yeom CH, Jung GC, Song KJ. Changes of terminal cancer patients’ health-related quality of life after high dose vitamin C administration. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:7–11. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahashi H, Mizuno H, Yanagisawa A. High-dose intravenous vitamin C improves quality of life in cancer patients. Personalized Medicine Universe. 2012;1:49e53. [Google Scholar]