Abstract

The syntheses of various lariat ethers including several not previously reported and their efficient purification are presented. The synthesis route brings together reactions from a variety of previous works leading to a robust and generalized approach to these C-pivot lariats. The main steps are condensation of functionalized diols with pentaethylene glycol ditosylate in the presence of potassium as a templating cation. Purification of the final products was achieved without chromatography by extracting from an aqueous potassium hydroxide solution.

Keywords: 18-crown-6, C-pivot lariat ethers, crown compounds, potassium hydroxide purification, macrocyles

Crown ethers have long been exploited as phase transfer agents in organic chemistry1 and thus their efficient preparation has attracted the attention of numerous researchers.2 An exciting variation of crown ethers involves the inclusion of a side arm on the macrocyclic which often contains metal coordinating heteroatoms. These lariat ethers, first studied by Gokel and co-workers,3 were found to confer unique cation binding properties.4 Carbon-pivot lariat ethers are a subclass of these compounds in which the side arm (podand) extend from a carbon atom in the macrocycle. These compounds often exhibit increased guest specificity.5,6

We have recently used lariat ethers as metal chelating leaving groups to expedite nucleophilic substitution reactions7 with emphasis on the expedited radiofluorination of small molecules.8 Following a similar strategy, we have appended chelating leaving groups to silicon for ultrafast silicon radiofluorination using K18F.9 In an attempt to further improve the efficiency of silicon fluorination, we have begun to use lariat ethers as nucleophilic catalysis. For this project, we required access to gram quantities of 18-crown-6 (18-C-6) containing side-arms possessing an hydroxyl group including some derivatives not previously reported. A careful review of the literature revealed a variety of lariat ether synthesis strategies and purification methods. These reports used either vacuum distillation or column chromatography as the purification method.10,11 In this letter, we report our development of an optimized route that takes advantage of various elements of previous reports to efficiently prepare a series of C-pivot 18-C-6 compounds.

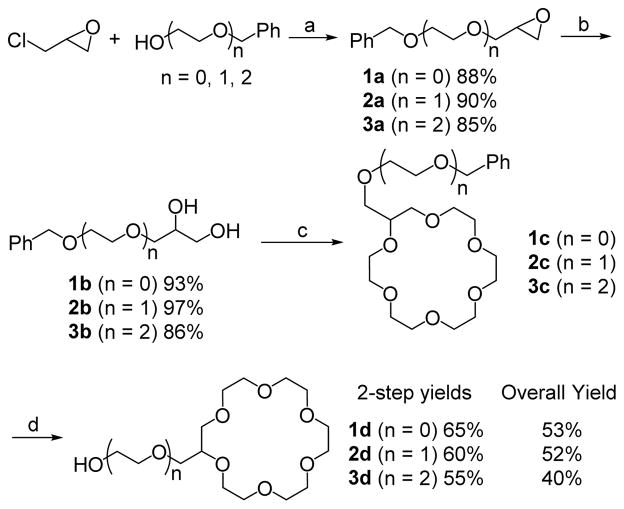

We began with the synthesis of lariats 1d – 3d (Scheme 1). Intermediate epoxides 1a - 3a were synthesized from reaction of the appropriate alcohol12 with epichlorohydrin in aqueous sodium hydroxide in the presence of catalytic TBAB.13 The resulting epoxides 1a – 3a were converted14 to functionalized diols 1b – 3b that were then reacted with pentaethylene glycol ditosylate and KOtBu in THF under reflux conditions to afford benzyl protected lariats 1c – 3c. These intermediates were debenzylated under hydrogenation conditions2c (H2/Pd-C) to afford 18-C-6 lariat ethers 1d – 3d in 55% to 65% two-step yields after purification.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Lariats 1d – 3d

Reagents and conditions: (a) 40% aq. NaOH, TBAB, 0 °C for 1 h and then r.t. for 24 h; (b) 2% H2SO4, r.t., 5 h; (c) KOtBu, pentaethyleneglycol ditosylate, THF, r.t. for 1h and then reflux for 48 h; (d) Pd-C, H2, EtOH, r.t., 48 h.

The overall yields for our lariat products were between 40% and 53%, a substantial improvement over previously reported methods. For example, for compound 1d, synthesized by a number of groups, our overall yield was 53% in four steps. Fukunishi and coworkers reported overall yields of 32% and 24% respectively for 1d using two different pathways with product isolation accomplished by chromatography on alumina.2c Others have reported overall yields of 31% and 35% of 1d using a distillation technique to purify the final compound.2d-2f

The only synthesis of 5d, reported in literature, uses a radical process to functionalize the 18-C-6 with allyl alcohol in 8% yield.2h Colera and coworkers report the synthesis of 7d in an overall yield of 11% in six steps2l compared to the 41% overall yield in 4 steps in this work. In this letter, we also report for the first time the synthesis of lariats 2d, 3d, 4d, and 6d.

The above route to obtain functionalized diols worked well for 1d – 3d since the starting materials, benzyl alcohol and its mono- and diethylene glycol derivatives, had reasonable aqueous solubility. This was not the case for the analogous reactions required to give lariats 4d – 7d containing alkanol side-arms. The analogous epichlorohydrin addition reactions (not shown) led to low yields (~10%) even after significant attempts at optimization. Therefore, an alternative approach was required. Our synthesis began with a benzylation step using NaH and BnBr to obtain alkene 4a - 7a.15 Diols 4b-7b were then prepared using OsO4/NMO following a literature procedure.16 Cyclization reactions between various diols and pentaethyleneglycol ditosylate followed by debenzylation afforded the desired crown ethers in reasonable overall yields (30 – 40%).

As mentioned, benzyl lariat ethers 1c - 7c were formed by condensation with pentaethylene glycol ditosylate in the presence of potassium tert-butoxide using the well-known template effect.17 These reactions usually required more than 48 hours for all starting material to be consumed. Upon completion, the reaction mixture contained byproducts that could not be conveniently separated using flash chromatography. A variety of traditional eluent systems and both silica gel and alumina stationary phases were evaluated to no avail. We carried forward these product mixtures to the hydrogenolysis step. The resulting mixture of debenzylated compounds was then separated on neutral alumina using a gradient elution of 1 – 10% 2-propanol/dichloromethane or 1–10% MeOH/EtOAc eluent system. However, this gradient method is a lengthy process requiring copious amounts of solvent (> 3 L for 3 g of crude).

In an attempt to isolate the final lariat products more efficiently, we sought to take advantage of their metal chelating properties to bring about a selective precipitation of the desired compound from the product mixture. A few reports demonstrate that complexation followed by precipitation using KBF4 is a feasible approach.18 Along these lines, we also found KNO3 to be effective in purifying lariat ether products by precipitation. However, these methods were problematic and unreliable on the multi-gram scale.

As an alternative, we developed a simplified extraction technique using aqueous potassium hydroxide. Thus crude debenzylated reaction mixtures (~5 g) were stirred with 50 mL of KOHaq (1 M) for 5 mins. After this time, the impurities were removed by extraction using ethyl acetate until TLC showed the absence of any impurity (usually three extractions). The water layer was then extracted with dichloromethane (3 times) (monitored by alumina TLC; 4% iPrOH/DCM eluent). The organic layer was collected; the solvent was removed in vacuo; and the resulting material was passed through a small plug of neutral alumina (10% MeOH/EtOAc as eluent) to furnish non-complexed lariat products. This process was significantly less tedious and offered nearly identical isolated yields as those based on flash chromatography.

In summary, bringing together reactions from a variety of previous works, we have developed a robust approach to a series C-pivot lariat ether compounds. This process involves the condensation of functionalized diols with pentaethylene glycol ditosylate in the presence of templating cations. Purification of the final products was achieved by a simple extraction method that obviated the need for tedious chromatography. We believe that this convenient synthesis of lariat ethers will facilitate their use as novel bifunctional catalysts.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Lariats 4d – 7d

Reagents and Conditions: (a) NaH, BnBr, THF, 0 °C to r.t. over 6 h; (b) OsO4, NMO, acetone/H2O, r.t., 12 h; (c) KOtBu, pentaethyleneglycol ditosylate, THF, r.t. for 1 h then reflux for 48 h (d) Pd-C, H2, EtOH, r.t., 48 h.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM110651) for financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information for this article is available online at http://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/journal/10.1055/s-00000083.

References and Notes

- 1.Pedersen CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:2495. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Montanari F, Tundo P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979:5055. [Google Scholar]; (b) Czech B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:4197. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fukunishi K, Czech B, Regen SL. J Org Chem. 1981;46:1218. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jungk SJ, Moore JA, Gandour RD. J Org Chem. 1983;48:1116. [Google Scholar]; (e) Ikeda I, Emura H, Okahara M. Synthesis. 1984:73. [Google Scholar]; (f) Bĕlohradský M, Stibor I, Holý P, Závada J. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 1987;52:2500. [Google Scholar]; (g) Zelechonok JB, Orlovskii VV, Zlotskii SS, Rakhmankulov DL. J Prakt Chem. 1990;332:719. [Google Scholar]; (h) Hiraoka M. Crown Ethers and Analogous Compounds. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1992. [Google Scholar]; (i) Ghosh AK, Bilcer G, Schiltz G. Synthesis. 2001:2203. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) List B, Castello C. Synlett. 2001:1687. [Google Scholar]; (k) Hu H, Bartsch RA. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2004;41:557. [Google Scholar]; (l) Colera M, Costero AM, Gavina P, Gil S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:2673. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gokel GW. Crown Ethers and Cryptands. Royal Society of Chemistry; Oxford, UK: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Gokel GW, Dishong DM, Diamond CJ. J Chem Soc, Chem Comm. 1980:1053. [Google Scholar]; (b) Goli DM, Dishong DM, Diamond CJ, Gokel GW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:5243. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gustowski DA, Echegoyen L, Goli DM, Kaifer A, Gokel GW. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:1633. [Google Scholar]; (d) Echegoyen L, Delgado M, Gatto VJ, Gokel GW. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:6825. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapi Z, Bakó P, Drahos L, Keglevich G. Heteroatom Chem. 2014;26:63. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Gokel GW. Chem Soc Rev. 1992;21:39. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gokel GW, Leevy WM, Weber ME. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2723. doi: 10.1021/cr020080k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gokel GW, Schall OF. Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry. Pergamon; New York: 1996. p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Lepore SD, Mondal D. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:5103. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lepore SD, Bhunia AK, Cohn P. J Org Chem. 2005;70:8117. doi: 10.1021/jo051241y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu S, Lepore SD, Li SY, Mondal D, Cohn PC, Bhunia AK, Pike VW. J Org Chem. 2009;74:5290. doi: 10.1021/jo900700j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-huniti MH, Lu S-Y, Pike VW, Lepore SD. J Fluorine Chem. 2014;158:48. doi: 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Späth A, König B. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2010;6:32. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.6.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Hu H, Bartsch RA. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2004;41:557. [Google Scholar]; (b) Czech BP, Desi DH, Koszuk J, Czech A, Babb DA, Robison TW, Bartsch RA. J Heterocyclic Chem. 1992;29:867. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jungk SJ, Moore JA, Gandour RD. J Org Chem. 1983;48:1116. [Google Scholar]; (d) Fukunishi K, Czeck B, Regan SL. J Org Chem. 1981;46:1218. [Google Scholar]; (e) Ikeda I, Yamamura S, Nakatsuji Y, Okahara M. J Org Chem. 1980;45:5355. [Google Scholar]; (f) Czech B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:4197. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao Q, Liu Y, Qiu Y, Zhou G, Mao C, Li Z, Yao ZJ, Jiang S. J Med Chem. 2011;54:525. doi: 10.1021/jm101053k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Almeida CG, Reis SG, de Almeida AM, Diniz CG, da Silva VL, Hyaric ML. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2011;78:876. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2011.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsujigami T, Sugai T, Ohta H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2001;12:2543. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Ginotra SK, Friest JA, Berkowitz DB. Org Lett. 2012;14:968. doi: 10.1021/ol203088g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mantovani SM, Angolini CFF, Marsaioli AJ. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2009;20:2635. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Borg T, Tuzina P, Somfai P. J Org Chem. 2011;76:8070. doi: 10.1021/jo2013466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nishizono N, Akama Y, Agata M, Sugo M, Yamaguchi Y, Oda K. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:358. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steed JW, Atwood JL. Supramolecular Chemistry. 2. J. Wiley & Sons; Chichester: 2009. p. 745. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montanari F, Tundo P. J Org Chem. 1982;47:1298. [Google Scholar]

- 19.General Procedure for the synthesis of benzyl protected 18-C-6 lariat ethers 1c-7c: To a solution of benzylated diol (1b-7b) (25 mmol) in THF (240 mL) was added KOtBu (100 mmol) at room temperature. After the mixture was allowed to react 1 h under a nitrogen atmosphere, a solution of pentaethylene glycol ditosylate (27.5 mmol) in THF (48 mL) of was added over a period of 1 h with stirring. The mixture was stirred for an additional 1 h at room temperature, refluxed for 24 h, and cooled to room temperature. The volatile solvents were removed by distillation under reduced pressure. The crude solids were dissolved in water and the resulting solution was extracted with DCM (5 × 20 mL). The combined organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After filtration and evaporation, the crude product (approx 3.5 g) was directly used for the debenzylation in the next step.

- 20.General Procedure for the synthesis of 18-C-6 lariat ethers 1d-7d: To a dry round bottom flask was added 10% (w/w) of 5% palladium on activated carbon and anhydrous EtOH (200 mL) was added to the reaction flask. The solution was degassed by bubbling the H2 gas through it twice. Benzylated lariat ethers (1c-7c) (approx 3.5 g) dissolved in anhydrous ethanol (20 mL) was added in to the reaction flask. The solution was degassed twice. The reaction mixture was stirred for 48 h under 1 atm of hydrogen. Thin-layer chromatography with alumina plates using 4% iPrOH/DCM as the eluent indicated the formation of product (Rf = 0.15). The product mixture was filtered and concentrated. The crude reaction mixture was then stirred into KOHaq (1 M, 50 mL) for 5 mins. After this time, the impurities were removed by extraction using ethyl acetate until TLC showed the absence of any impurity (usually three extractions). The water layer was then extracted with dichloromethane (3 times) (monitored by alumina TLC; 4% iPrOH/DCM eluent). The organic layer was collected; the solvent was removed in vacuo; and, the resulting material was passed through a small plug of neutral alumina (10% MeOH/EtOAc as eluent) to furnish non-complexed lariat products.2-Hydroxymethyl-18-C-6 (1d):2a-2g Obtained in 65% yield (1.74 g) as a colorless viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 2.93 (s, 1H, OH), 3.46–3.82 (m, 25H, 12 x CH2 & 1 x CH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 63.0 (CH2OH), 69.6 (CH2O), 70.6 (CH2O), 70.7 (CH2O), 70.75 (2 x CH2O), 70.8 (CH2O), 70.83 (CH2O), 71.0 (CH2O), 71.03 (CH2O), 71.2 (CH2O), 71.8 (CH2O), 79.4 (CH). HRMS (ESI) (M+H): calculated for C13H26O7 is 295.1757; found 295.1751.2-(Hydroxy-(ethoxymethyl))-18-C-6 (2d): Obtained in 60% yield (1.66 g) as a colorless viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 2.84 (s, 1H, OH), 3.50–3.84 (m, 29H, 14 x CH2 & 1 x CH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 61.8 (CH2OH), 69.8 (CH2O), 70.7 (CH2O), 70.73 (CH2O), 70.77 (CH2O), 70.8 (CH2O), 70.83 (CH2O), 70.9 (CH2O), 70.95 (CH2O), 71.0 (CH2O), 71.1 (CH2O), 71.13 (CH2O), 71.4 (CH2O), 72.7 (CH2O), 78.3 (CH). HRMS (ESI) (M+H): calculated for C15H30O8 is 339.2019; found 339.2017.2-(Hydroxy-(ethoxy)-(ethoxymethyl)))-18-C-6 (3d): Obtained in 55% yield (1.56 g) as a colorless viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 2.76 (s, 1H, OH), 3.47–3.81 (m, 33H, 16 x CH2 & 1 x CH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 61.8 (CH2OH), 69.9 (CH2O), 70.4 (CH2O), 70.6 (CH2O), 70.7 (2 x CH2O), 70.73 (CH2O), 70.76 (CH2O), 70.8 (CH2O), 70.9 (2 x CH2O), 70.93 (CH2O), 71.0 (CH2O), 71.4 (CH2O), 71.5 (CH2O), 72.6 (CH2O), 78.3 (CH). HRMS (ESI) (M+H): calculated for C17H34O9 is 383.2281; found 383.2276.2-Hydroxyethyl-18-C-6 (4d): Obtained in 50% yield (1.35 g) as a colorless viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 1.65–1.85 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.01 (s, 1H, OH), 3.58–3.75 (m, 22H, 11 x CH2), 3.75–3.90 (m, 3H, 1 x CH2 & 1 x CH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 34.8 (CH2), 60.1 (CH2OH), 69.4 (CH2O), 70.6 (CH2O), 70.7 (CH2O), 70.77 (CH2O), 70.8 (CH2O), 70.86 (CH2O), 70.9 (CH2O), 71.0 (CH2O), 71.05 (CH2O), 71.7 (CH2O), 74.5 (CH2O), 77.7 (CH). HRMS (ESI) (M+H): calculated for C14H28O7 is 309.1913; found 309.1908.2-Hydroxypropyl-18-C-6 (5d):2h Obtained in 48% yield (1.31 g) as a colorless viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 1.51–1.68 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 2.30 (s, 1H, OH), 3.50–3.76 (m, 24H, 12 x CH2), 3.83–3.88 (m, 1H, 1 x CH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 28.5 (CH2), 28.9 (CH2), 62.8 (CH2OH), 69.6 (CH2O), 70.6 (CH2O), 70.68 (CH2O), 70.7 (CH2O), 70.9 (2 x CH2O), 70.91 (CH2O), 70.92 (CH2O), 70.94 (CH2O), 71.0 (CH2O), 74.2 (CH2O), 79.0 (CH). HRMS (ESI) (M+H): calculated for C15H30O7 is 323.2070; found 323.2064.2-Hydroxybutyl-18-C-6 (6d): Obtained in 45% yield (1.24 g) as a colorless viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 1.26–1.62 (m, 6H, 3 x CH2), 2.48 (s, 1H, OH), 3.62–3.74 (m, 24H, 12 x CH2), 3.80–3.85 (m, 1H, 1 x CH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 21.9 (CH2), 31.5 (CH2), 32.9 (CH2), 62.7 (CH2OH), 69.5 (CH2O), 70.67 (4 x CH2O), 70.7 (CH2O), 70.8 (CH2O), 70.9 (CH2O), 71.0 (CH2O), 71.1 (CH2O), 74.3 (CH2O), 79.3 (CH). HRMS (ESI) (M+H): calculated for C16H32O7 is 337.2226; found 337.2221.1,2-Dihydroxymethyl-18-C-6 (7d):2l Obtained in 55% yield (1.24 g) as a colorless viscous oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 2.60 (s, 1H, OH), 3.44 (s, 1H, OH), 3.59–3.84 (m, 26H, 12 x CH2 & 2 x CH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 61.8 (2 x CH2OH), 70.2 (2 x CH2O), 70.3 (2 x CH2O), 70.5 (2 x CH2O), 70.9 (2 x CH2O), 70.91 (2 x CH2O), 80.7 (2 x CH). HRMS (ESI) (M+H): calculated for C14H28O8 is 325.1862; found 325.1857.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.