Abstract

A previously healthy 65-year-old man presented with a two-week history of weight loss, headaches, blurred vision, asthenia and quickly worsening walking impairment. He denied photophobia, neck stiffness, fever, nausea or vomiting.

Neurological examination showed global motor slowing, tendency to fall asleep during the clinical examination, generalized weakness against resistance to head and limbs, and osteotendon reflexes present in the upper limbs, but not evoked in the lower limbs. No sensitive deficit or focal neurologic sign was recognizable.

Non-contrast multislice computed tomography (MSCT) of the head was performed in the emergency department, showing diffuse periventricular white matter and thalamic mild hyperdensity.

Lumbar puncture, blood tests, including serology for HIV and other infections, were negative.

On the third day the patient, showing decreased consciousness, underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast medium injection. MRI revealed the presence of multiple pseudonodular avidly enhancing lesions, supra and infratentorial, crossing the midline, involving the ventricular system, including the fourth ventricle, with extension into the surrounding white matter, the corpus callosum, the thalamus and the hypothamalus.

A stereotactic biopsy led to a diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primarily located in the central nervous system (PCNSL).

After the completion of the first phase of treatment (immunotherapy with intravenous Rituximab and corticosteroid), the MRI showed a marked regression of tumor masses.

Keywords: primary central nervous system lymphoma, neuroimaging, CT and MR imaging, lymphoma, central nervous system

Introduction

The incidence of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) has been increasing in recent years,1 accounting now for 2–6% of all intracranial tumors,1 although it is considered an uncommon aggressive tumor. Most PCNSL is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (>95%) whereas T-cell lymphomas are rare.2

Clinical presentation and imaging findings can vary according to the immune status of the patient.2

Most lesions are usually solitary (65%), although multiple lesions are not uncommon (35%).3

PCNSL typically presents as an intra-axial lesion, particularly in the supratentorial region; only 9–13% of patients have infratentorial lesions.2 It can involve various anatomical locations, mainly basal ganglia, thalami, corpus callosum and periventricular white matter.

Lesions are bilateral and cross the midline in about half of all of patients.

Contact with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), ependymal or pial, is identifiable in nearly 97% of cases and highly suggestive for PCNSL.4

Only a few cases of PCNSL have been reported in the hypothalamus and fourth ventricle.5–9

Case report

A previously healthy 65-year-old man presented with a two-week history of weight loss, headaches, blurred vision, asthenia and quickly worsening walking impairment.

He denied photophobia, neck stiffness, fever, nausea or vomiting.

Neurological examination showed global motor slowing, tendency to fall asleep during the clinical examination, generalized weakness against resistance to head and limbs, and osteotendon reflexes present in the upper limbs, but not evoked in the lower limbs. No sensitive deficit or focal neurologic sign was recognizable.

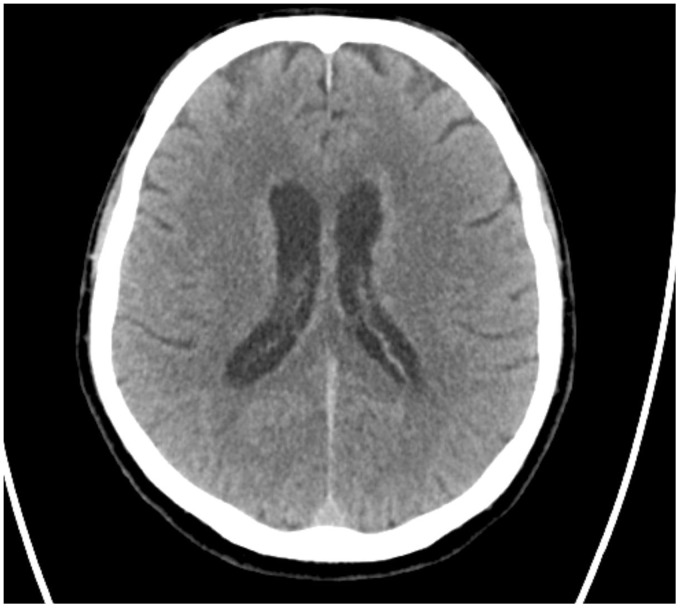

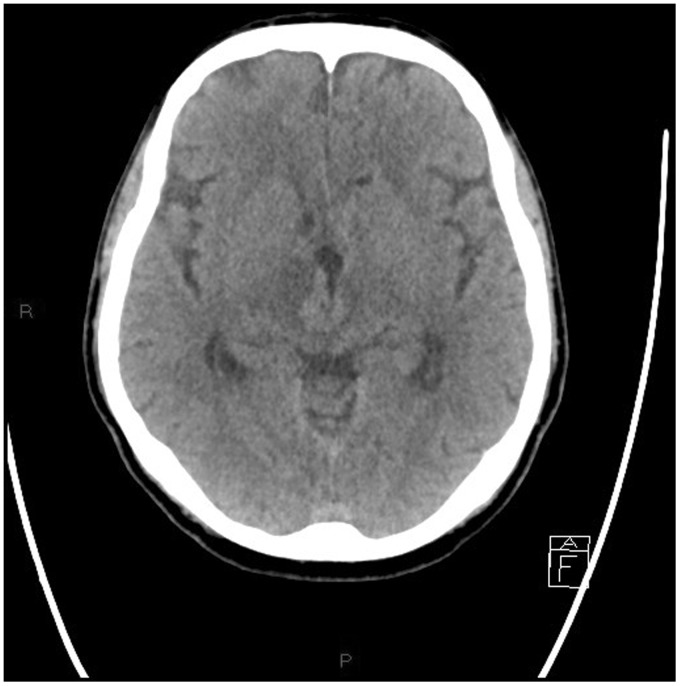

Non-contrast multislice computed tomography (MSCT) of the head was performed in the emergency department, showing diffuse periventricular white matter and thalamic (Figures 1–4) mild hyperdensity.

Figure 1.

Unenhanced head computed tomography (CT): diffuse mild hyperdensity surrounding the lateral ventricles.

Figure 2.

Unenhanced head computed tomography (CT): diffuse mild hyperdensity surrounding the lateral and the third ventricle.

Figure 3.

Unenhanced head computed tomography (CT): hyperdense mass originating from the walls of the third ventricle extending into the thalamus. Hyperdense pseudonodular lesions involving the hippocampus and surrounding the atrium of the lateral ventricles.

Figure 4.

Unenhanced head computed tomography (CT): mild hyperdensity surrounding the fourth ventricle.

Lumbar puncture, blood tests, including serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other infections, were negative.

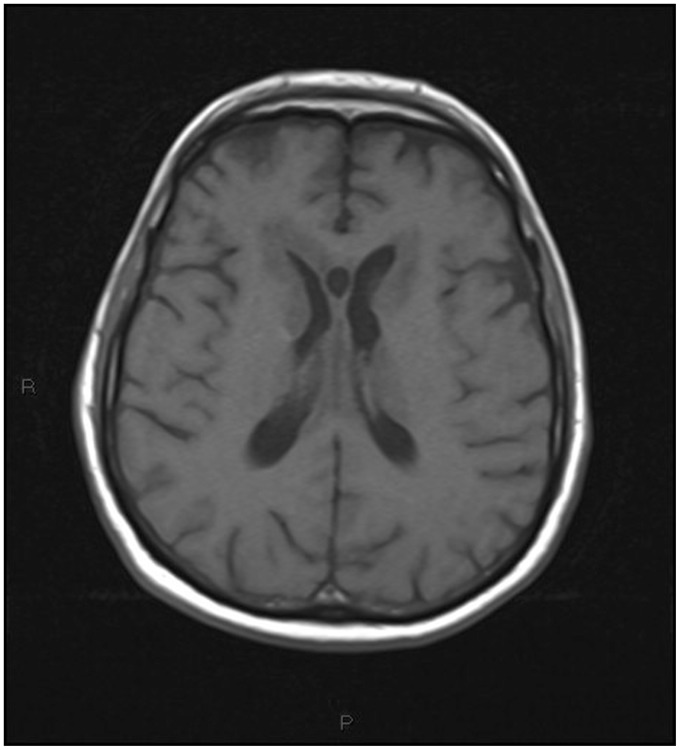

On the third day the patient, showing decreased consciousness, underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast medium injection (Figures 5–15).

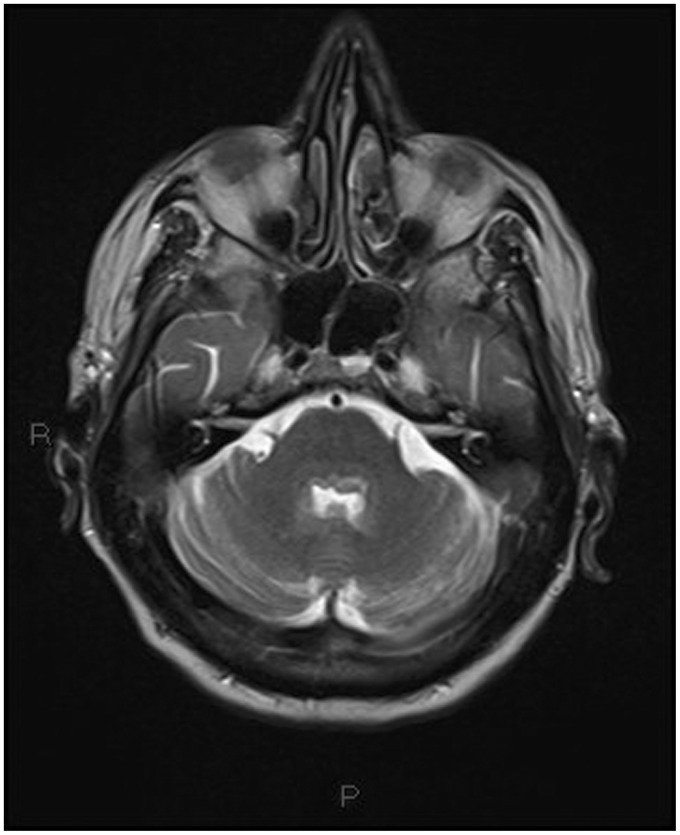

Figure 5.

T1-weighted transverse image: extensive hypointense mass lesion originating from the ventricular wall extending into the white matter.

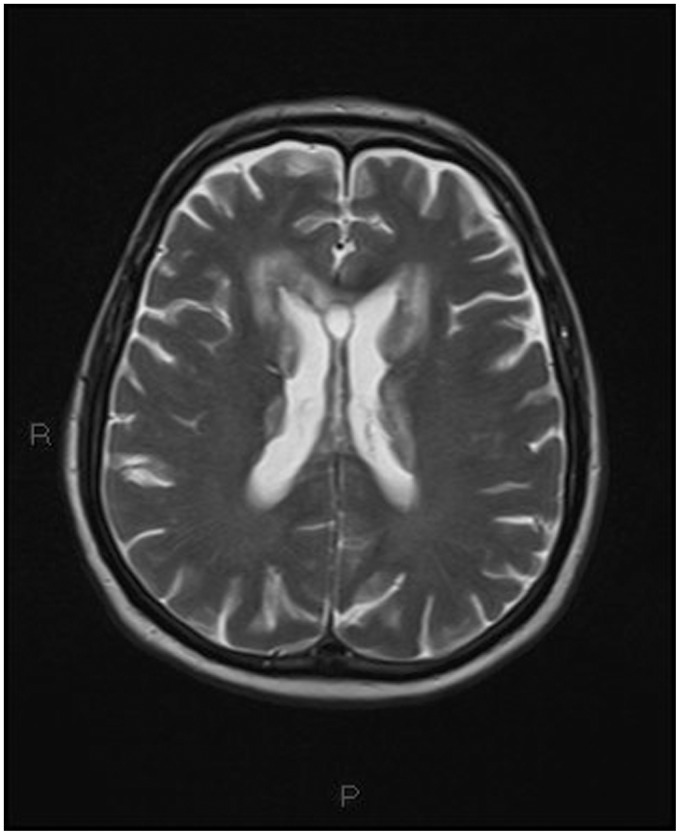

Figure 6.

T2-weighted transverse image: the same plane as Figure 5 showing extensive inhomogeneous, mainly hypointense mass lesion and perilesional edema.

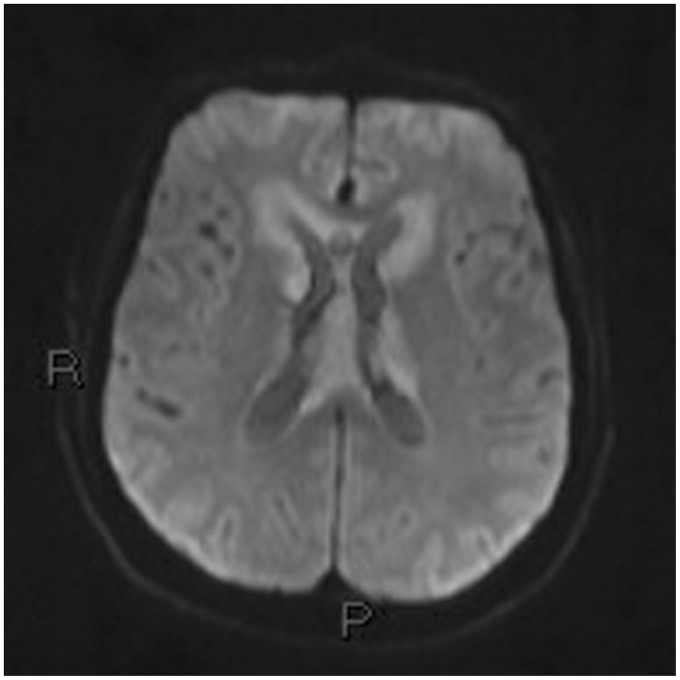

Figure 7.

Diffusion-weighted image b600 and the ADC map: the same plane as Figures 5 and 6 showing periventricular hyperintensity. The core of the hyperintensity shows restricted diffusion in the ADC map, the perilesional hyperintensity in the ADC map corresponds to mild perilesional edema. ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient.

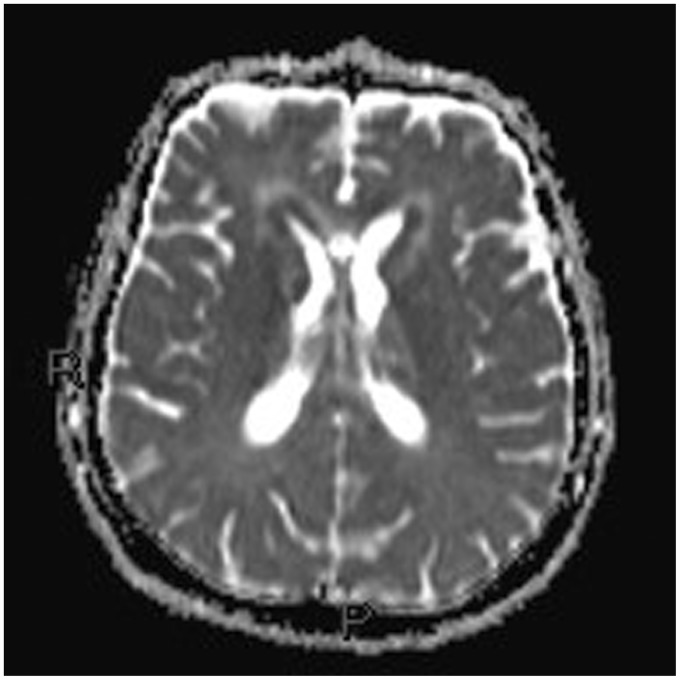

Figure 8.

Diffusion-weighted image b600 and the ADC map: the same plane as Figures 5 and 6 showing periventricular hyperintensity. The core of the hyperintensity shows restricted diffusion in the ADC map, the perilesional hyperintensity in the ADC map corresponds to mild perilesional edema. ADC: apparent diffusion coefficient.

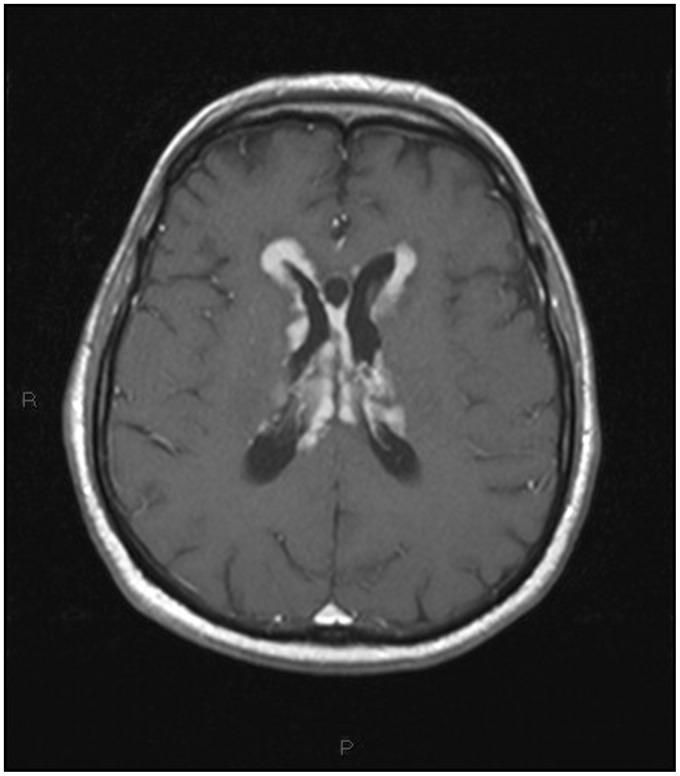

Figure 9.

T1-weighted transverse image after contrast administration: the same plane as Figures 5–8 showing marked and homogeneous pseudonodular periventricular contrast enhancement without evidence of necrosis.

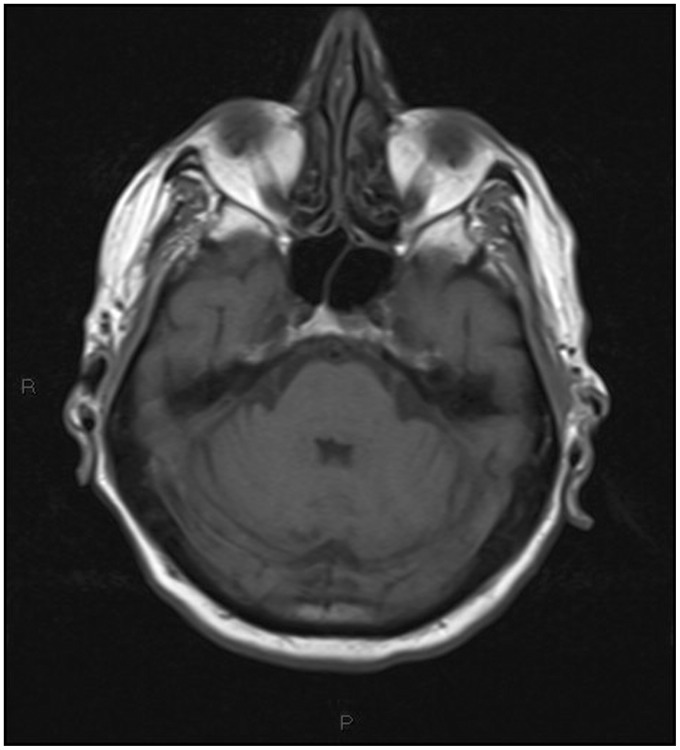

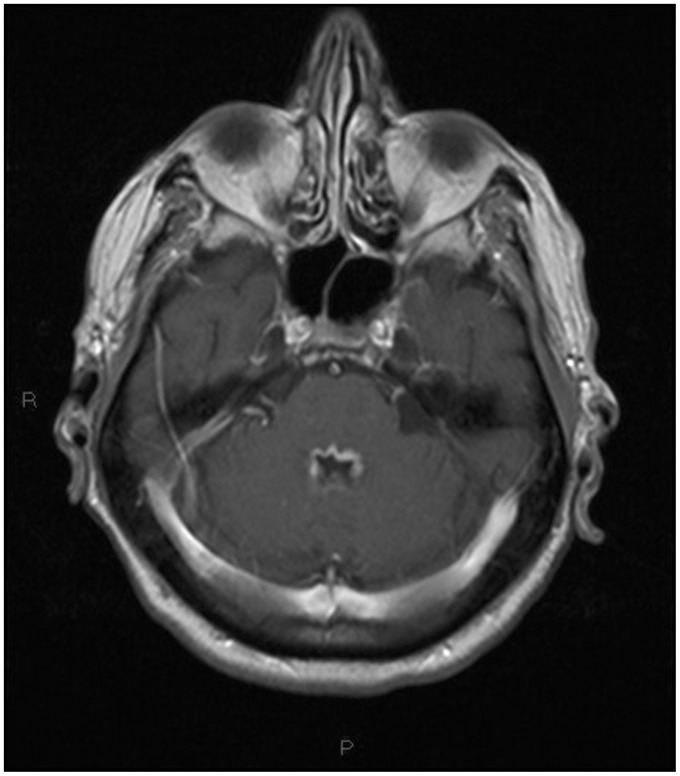

Figure 10.

T1-weighted transverse image of the posterior fossa showing mild hypointensity surrounding the fourth ventricle.

Figure 11.

T2-weighted transverse image: the same plane as Figure 10 showing inhomogeneous hyperintensity surrounding the fourth ventricle.

Figure 12.

T1-weighted transverse image after contrast administration: the same plane as Figures 10 and 12. Marked homogeneous periventricular contrast enhancement. No significant perilesional edema was found.

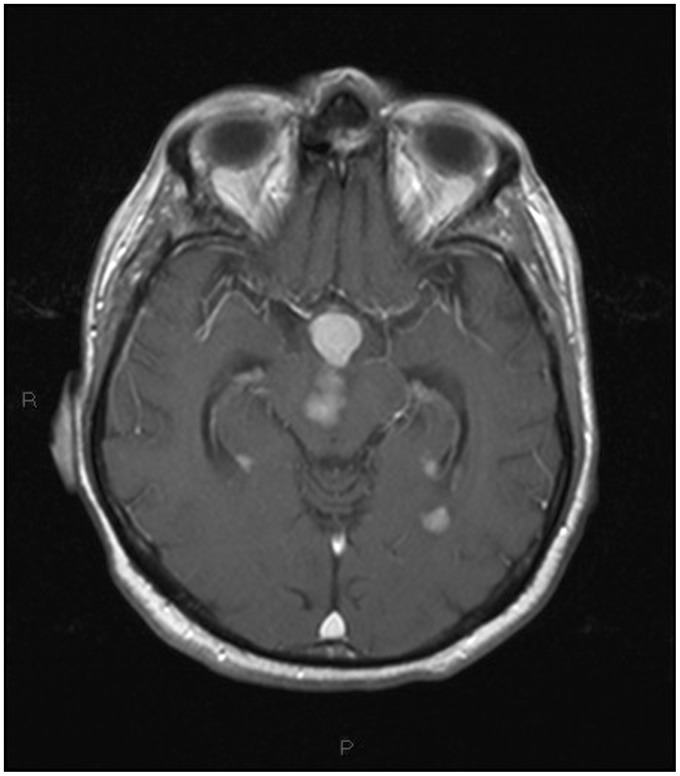

Figure 13.

T1-weighted transverse image after contrast administration showing a well-defined hypothalamic lesion with marked homogeneous contrast enhancement, multifocal avidly enhancing pseudonodular masses located in the midbrain and close to the temporal horns.

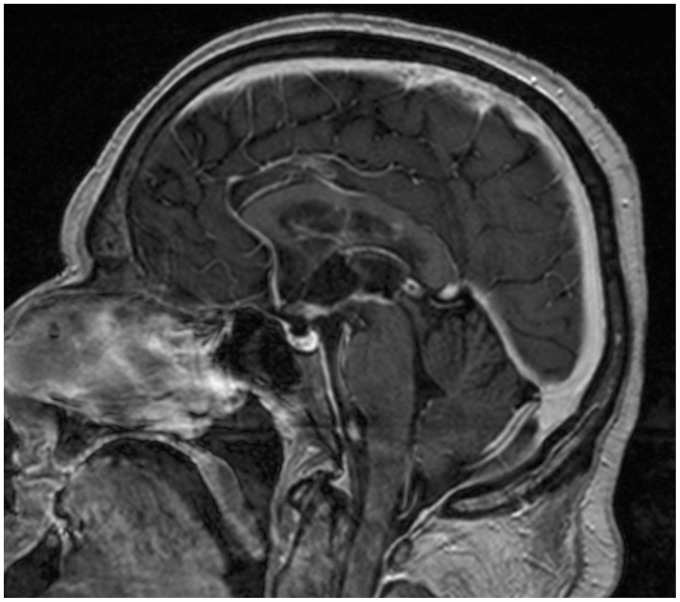

Figure 14.

Sagittal T1-weighted post – contrast medium injection image highlighting the corpus callosum, third ventricle floor, hypothalamic and fourth ventricle involvement.

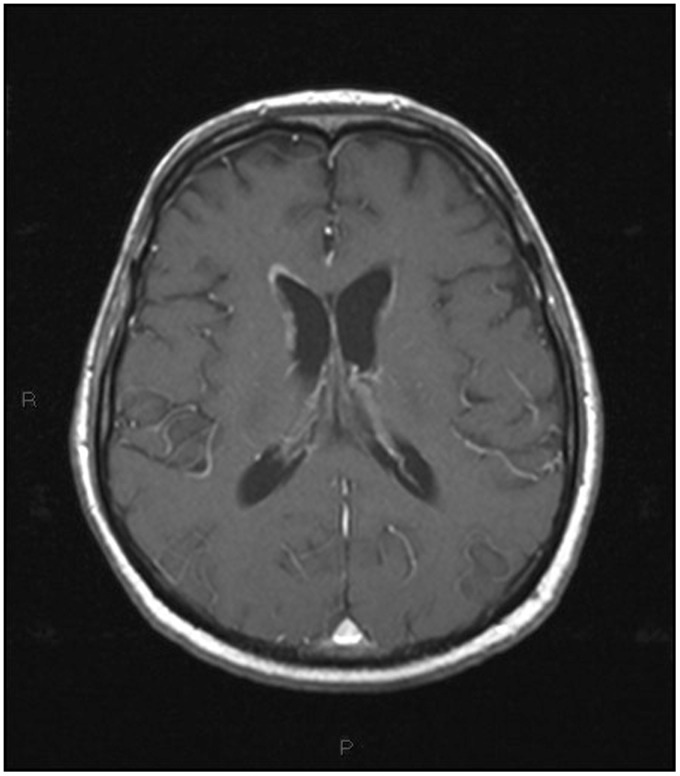

Figure 15.

Post-treatment magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). T1-weighted transverse image after contrast administration, the same plane as Figure 9. Marked regression of the previous periventricular contrast enhancement.

A stereotactic biopsy led to the diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, primarily located in the central nervous system.

Immunohistochemistry showed tumor cells positive for CD20 and negative for CD3 and CD10.

Bone marrow biopsy and MSCT of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis excluded a systemic dissemination.

Two weeks after the completion of the first phase of treatment (immunotherapy with intravenous Rituximab and corticosteroid), the MRI showed a marked regression of tumor masses (Figures 15 and 16).

Figure 16.

Post-treatment magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). T1-weighted sagittal image after contrast administration, the same plane as Figure 14. Previously detected lesions are almost no longer recognizable.

Discussion

The most remarkable finding of our case is the extended localization of the tumor, involving uncommon anatomical structures.

In fact the majority of lesions are supratentorial. Infratentorial lesions are rare (9–13%).1

Few cases of PCNSL (five affecting the hypothalamus and six the fourth ventricle) have been described so far.10–15

To the best of our knowledge, mutual involvement of the hypothalamus and fourth ventricle by PCNSL has not been reported yet.

Also, considering that our patient was immunocompetent, the number of the lesions and their huge extension were unusual.

The contact with a CSF surface, as in our case, is typical of PCNSL. The involvement of the corpus callosum was characteristic as well.

On MSCT the lesions were hyperdense, as typical, due to the densely packed abnormal cells. The mass effect was not prominent.

On MRI the lesions were hypointense on T1 and inhomogeneous on T2-weighted images.

Lesions demonstrated the typical restricted diffusion,16 due to the high cellularity, and the typical marked homogeneous enhancement.

Although marked edema surrounding the lesions is a common finding, in our case we did not observe significant perilesional edema.

In our case MSCT findings have greatly underestimated the underlying advanced stage of the disease, clearly evident on MRI.

As is already known, the radiological diagnosis of PCNSL is often difficult because imaging findings of lymphoma may mimic other pathologies,16 often necessitating a stereotactic biopsy.

After treatment, the fast regression of the enhanced areas was strongly suggestive of PCNSL.17

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.van der Sanden GA, Schouten LJ, van Dijck JA, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphomas: Incidence and survival in the Southern and Eastern Netherlands. Cancer 2002; 94: 1548–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yap KK, Sutherland T, Liew E, et al. Magnetic resonance features of primary central nervous system lymphoma in the immunocompetent patient: A pictorial essay. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2012; 56: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Küker W, Nägele T, Korfel A, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphomas (PCNSL): MRI features at presentation in 100 patients. J Neurooncol 2005; 72: 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutherland T, Yap K, Liew E, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: A retrospective review of MRI features. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2012; 56: 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biasiotta A, Frati A, Salvati M, et al. Primary hypothalamic lymphoma in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: Case report and review of the literature. Neurol Sci 2010; 31: 647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascual JM, Gonzáles-Llanos F, Roda JM. Primary hypothalamic third ventricle lymphoma. Case report and review of literature. Neurocirugia (Astur) 2002; 13: 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capra M, Wherrett D, Weitzman S, et al. Pituitary stalk thickening and primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Neurooncol 2004; 67: 227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee MT, Lee Ti, Won JG, et al. Primary hypothalamic lymphoma with panhypopituitarism presenting as stiff-man syndrome. Am J Med Sci 2004; 328: 124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antic D, Smiljanic M, Bila J, et al. Hypothalamic dysfunction in a patient with primary lymphoma of the central nervous system. Neurol Sci 2012; 33: 387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werneck LC, Hatschbach Z, Mora AH, et al. Meningitis caused by primary lymphoma of the central nervous system. Report of a case [article in Portuguese]. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1977; 35: 366–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haegelen C, Riffaud L, Bernard M, et al. Primary isolated lymphoma of the fourth ventricle: Case report. J Neurooncol 2001; 51: 129–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill CS, Khan AF, Bloom S, et al. A rare case of vomiting: Fourth ventricular B-cell lymphoma. J Neurooncol 2001; 93: 261–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brar R, Prasad A, Sharma T, et al. Multifocal lateral and fourth ventricular B-cell primary CNS lymphoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2012; 114: 281–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bokhari R, Ghanem A, Alahwal M, et al. Primary isolated lymphoma of the fourth ventricle in an immunocompetent patient. Case Rep Oncol Med 2013; 2013: 614–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao RN, Mishra D, Agrawai P, et al. Primary B-cell central nervous system lymphoma involving fourth ventricle: A rare case report and a review of literature. Neurol India 2013; 61: 450–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khurjekar D, Bonicelli C, Bacci A, et al. Importance of functional MRI and the role of stereotactic biopsy in the diagnosis of cerebral lymphoma. Neuroradiol J 2008; 21: 551–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adachi K, Yamaguchi F, Node Y, et al. Neuroimaging of primary central nervous system lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: Comparison of recent and previous findings. J Nippon Med Sch 2013; 80: 174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]