Abstract

Complications associated with intra-arterial infusion of vasodilator agents for the treatment of vasospasm associated with a ruptured cerebral aneurysm are extremely rare. We present the case of a patient who developed left lower extremity monoplegia following intra-arterial infusion of verapamil for treatment of diffuse cerebral vasospasm, 6 days after initially undergoing treatment of a ruptured right A1-2 junction aneurysm. A repeat angiogram following this intra-arterial vasodilator treatment demonstrated a coil loop which had herniated into the right A2 artery. Herein, we describe a previously unreported complication which occurred following intra-arterial pharmacologic vasospasm treatment, review the existing literature, and suggest potential causes and treatment options.

Keywords: Cerebral aneurysm, coil herniation, coil embolization, stroke, verapamil, cerebral vasospasm

Background

Coil herniation into the parent artery and associated thromboembolism is a rare but serious complication of endovascular coil embolization of cerebral aneurysms.1,2 We present a previously unreported case of coil herniation following intra-arterial verapamil therapy for vasospasm treatment, and emphasize the importance of post-operative care and examination for early detection and potential treatment of this rare complication.

Case presentation

A 52-year-old right-handed man presented with a Hunt & Hess grade 3, Fisher grade 3 subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). He underwent an uncomplicated balloon-assisted coil embolization of a ruptured 4 mm aneurysm originating from the right A1 and A2 junction using a Scepter 4 × 11 mm XC dual-lumen balloon microcatheter (MicroVention Inc.; Tustin, CA, USA) and Target® platinum coils (Stryker Neurovascular; Freemont, CA, USA) (Figure 1). At the conclusion of the procedure, the aneurysm was noted to be completely obliterated.

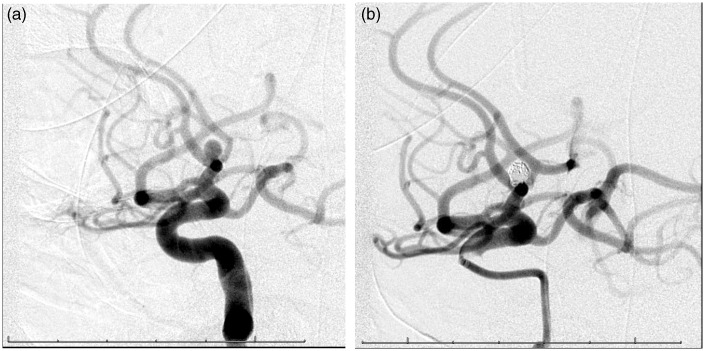

Figure 1.

Lateral right internal carotid artery angiogram demonstrating aneurysm arising from A1/A2 junction before coiling (a) and after coiling (b).

Following the intervention, the patient was started on aspirin 325 mg daily and nimodipine 60 mg every 4 h for vasospasm prophylaxis. He remained neurologically intact, though his post-operative course was complicated by a right lower extremity deep vein thrombosis discovered on routine screening 4 days post-procedurally, for which the patient was started on intravenous heparin with a goal partial thromboplastin time of 50–80.

Over the next several days he demonstrated mild increases in his transcranial Doppler velocities, but remained grossly neurologically intact. On post-operative day 6, a follow-up diagnostic cerebral arteriogram was performed to screen for cerebral vasospasm. The angiogram demonstrated diffuse moderate vasospasm within the anterior circulation, which was most severe in the bilateral anterior cerebral artery territories (Figure 2). Given the severity of the radiographic spasm as well as the difficulty associated with clinical diagnosis of anterior cerebral spasm, we elected to pursue pharmacologic intra-arterial treatment. Through a diagnostic catheter placed in the ascending cervical segment of the internal carotid artery (ICA), 10 mg of verapamil was slowly delivered into the left ICA over 10 min, followed by the same procedure within the right ICA. Follow-up runs demonstrated very slight increases in vessel caliber.

Figure 2.

Anterior-posterior left (a) and right (b) internal carotid angiogram demonstrating bilateral vasospasm of anterior cerebral arteries.

Shortly after his return to the intensive care unit (ICU), the patient developed left lower extremity monoplegia. A non-contrasted CT head showed a slight interval increase in ventriculomegaly, which prompted external ventricular drain placement. In addition, a systolic blood pressure floor of 160 mmHg was instituted. Over the subsequent 4 h, the patient’s left lower extremity strength did not improve.

Investigations and findings

Another non-contrasted CT head was performed, due to concern for an ischemic event due to symptomatic vasospasm, despite the intra-arterial vasospasm treatment earlier in the day. Imaging demonstrated a new right-sided anterior cerebral artery (ACA) territory infarct (Figure 3). Cerebral angiography was then repeated which demonstrated that a loop of coil had herniated into the right A2 segment, which was markedly narrowed (Figure 4). Given the presence of significant concomitant vasospasm both proximally and distally in the ACA territory, additional verapamil (10 mg) was infused with improvement in vessel caliber. Due to the fact that the patient exhibited a complete stroke on head CT and given the risk of further coil dislodgement, no further mechanical intervention was performed at this time. Of note, upon retrospective review of the scout image of the patient’s prior head CT at this point, the subtle coil herniation could be visualized (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Ischemic infarct in right ACA distribution on non-contrasted axial head CT.

Figure 4.

Herniated coil loop on anterior-posterior right internal carotid angiogram.

Figure 5.

CT head scout image demonstrating herniated coil.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was returned to the ICU, where the systolic blood pressure floor of 160 mmHg was maintained. Over the span of the subsequent 2 weeks, his proximal left lower extremity muscles improved to antigravity strength, though he remained at 1/5 strength distally. The patient ultimately required placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt and was transitioned to oral warfarin therapy and discharged to rehab 30 days after initial presentation. On subsequent follow-up 1 month after discharge to rehab, the patient’s left lower extremity muscles improved to full strength proximally and 3/5 strength distally.

Discussion

Delayed ischemia due to vasospasm is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients who initially survive an aneurysmal SAH.3 This delayed narrowing of the cerebral vessels most often occurs 3–14 days after the hemorrhagic event and generally manifests as mental status changes or new focal neurological deficits.4 Routine monitoring of arterial cerebral blood flow with transcranial Dopplers is also employed for early diagnosis of vasospasm. While medical therapies for vasospasm prophylaxis and management do exist, patients sometimes require endovascular management in the form of intra-arterial vasodilator administration and/or transluminal balloon angioplasty.

Verapamil is a calcium channel blocker that inhibits voltage-gated calcium channels in arterial smooth muscle cells, resulting in vasodilation. Intra-arterial infusion of verapamil has been shown in a number of studies to be efficacious in treating vasospasm as well as in preventing catheter-induced vasospasm.5–7 Importantly, intra-arterial verapamil also appears to have minimal effects on blood pressure, heart rate, or intracranial pressure. With the exception of one case report of tonic-clonic seizures associated with intra-arterial verapamil infusion, no major complications have been previously reported in the literature.8 In the present case, we describe the first report of a thromboembolic event related to coil herniation after intra-arterial verapamil therapy for vasospasm.

Overall, the incidence of coil herniation is estimated between 2.4% and 4.2%.1,2 Following a coil embolization of an aneurysm, the conglomerate coil mass within the aneurysm is generally believed to be stable, with any movement or migration of coils after placement usually evident prior to the conclusion of procedure. Though there have been limited case reports of delayed coil herniation resulting in thromboembolic events,9–14 the reasons for coil prolapse are not well understood. Risk factors include wide-necked aneurysms and coil mismatch with the aneurysmal size. Proposed mechanisms leading to coil herniation include coil instability after detachment, placement of excessive undersized coils at the neck of the aneurysm, herniation during microcatheter removal, resorption of pre-existing aneurysmal thrombus, or displacement during placement of coils.1,10,13,14 In our case, we propose that dilatation of constricted arteries adjacent to the aneurysm by verapamil led to slight alteration of the morphology of the aneurysm neck, which, in turn, may have triggered coil herniation. Given the thrombogenic nature of these coils, the patient’s ischemic stroke was most likely due to the coil herniation into the ACA, in conjunction with arterial constriction secondary to vasospasm.

Many options exist in the management of coil herniation, which include using a snare to remove the coil,15 balloon-remodeling to replace the coil back into the aneurysm sac,16 or placing a neck remodeling device to trap the herniated coil against the parent vessel wall.1,17–19 In our case, because the patient had a complete infarction at the time of the discovery of the herniated coil loop, and given the concern for exacerbation of the herniation with additional manipulation, we did not pursue a salvage procedure.

In conclusion, we demonstrate a rare but serious complication of intra-arterial verapamil for treatment of radiographic vasospasm after aneurysmal SAH. Clinicians should be aware of the potential for complications associated with the use of intra-arterial verapamil, and consider limiting its use to symptomatic, medically refractory vasospasm.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Luo CB, Chang FC, Teng MMH, et al. Stent management of coil herniation in embolization of internal carotid aneurysms. Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 1951–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renowden SA, Benes V, Bradley M, et al. Detachable coil embolization of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A single center study, a decade experience. J Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2009; 111: 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macdonald RL, Pluta RM, Zhang JH. Cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: The emerging revolution. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2007; 3: 256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janardhan V, Biondi A, Riina HA, et al. Vasospasm in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Diagnosis, prevention, and management. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2006; 16: 483–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng L, Fitzsimmons BF, Young WL, et al. Intraarterially administered verapamil as adjunct therapy for cerebral vasospasm: Safety and 2-year experience. Am J Neuroradiol 2002; 23: 1284–1290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi S, Young WL, Pile-Spellman J, et al. Manipulation of cerebrovascular resistance during internal carotid artery occlusion by intraarterial verapamil. Anesth Analg 1997; 85: 753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keuskamp J, Murali R, Chao KH. High-dose intraarterial verapamil in the treatment of cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2008; 108: 458–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westhout FD, Nwagwu CI. Intra-arterial verapamil-induced seizures: Case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 2007; 67: 483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiorella D, Kelly ME, Moskowitz S, et al. Delayed symptomatic coil migration after initially successful balloon-assisted aneurysm coiling: Technical case report. Neurosurgery 2009; 64: 391–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao BL, Li MH, Wang YL, et al. Delayed coil migration from a small wide-necked aneurysm after stent-assisted embolization: Case report and literature review. Neuroradiology 2006; 48: 333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haraguchi K, Houkin K, Nonaka T, et al. Delayed thromboembolic infarction associated with reconfiguration of Guglielmi detachable coils – case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2007; 47: 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motegi H, Isobe M, Isu T, et al. A surgical case of delayed coil migration after balloon-assisted embolization of an intracranial broad-neck aneurysm: Case report. Neurosurgery 2010; 67: 516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phatouros CC, McConachie NS, Jaspan T. Post-procedure migration of Guglielmi detachable coils and mechanical detachable spirals. Neuroradiology 1999; 41: 324–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sim KB, Park JK, Kwon OK, et al. Delayed herniation of coil loop and spontaneous reposition in a superior cerebellar artery aneurysm. NeuroIntervention 2011; 6: 31–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dinc H, Kuzeyli K, Kosucu P, et al. Retrieval of prolapsed coils during endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms. Neuroradiology 2006; 48: 269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiu K, Martin JB, Jean B, et al. Rescue balloon procedure for an emergency situation during coil embolization for cerebral aneurysms. Technical note. J Neurosurg 2002; 96: 373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fessler RD, Ringer AJ, Qureshi AI, et al. Intracranial stent placement to trap an extruded coil during endovascular aneurysm treatment: Technical note. Neurosurgery 2000; 46: 248–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schutz A, Solymosi L, Vince GH, et al. Proximal stent fixation of fractured coils: Technical note. Neuroradiology 2005; 47: 874–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoo E, Kim DJ, Kim DI, et al. Bailout stent deployment during coil embolization of intracranial aneurysms. Am J Neuroradiol 2009; 30: 1028–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]