Abstract

Spontaneous “non-moyamoya” arterial occlusion of the intracranial arteries is very unusual. Progressive occlusion of a major intracranial artery, independently from the etiology, can lead to the development of collateral arterial networks that supply blood flow to distal territories beyond the occlusion. These collateral arteries are typically small and conduct low flows, but the hemodynamic stress within them can lead to aneurysm formation within the collateral network. In this report we present a case of spontaneous internal carotid artery occlusion and collateral network aneurysm for the first time in the literature and discuss the main features of the etiology and endovascular treatment of this rare, challenging aneurysm.

Keywords: Internal carotid artery, spontaneous occlusion, collateral aneurysm, endovascular management

Introduction

Spontaneous “non-moyamoya” arterial occlusion and collateral network aneurysm formation are very unusual. In the recent literature, the available information about this issue is based on a single or small group of cases.1 The exact etiology of aneurysm formation on collateral network and treatment strategies are very controversial. Most of the reported cases were treated surgically by aneurysm trapping, clipping, or by-pass surgery.1 In this report, we describe right internal carotid artery (ICA) spontaneous occlusion and ruptured “collateral network” aneurysm concomitance. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report about spontaneous ICA occlusion and collateral network aneurysm formation. Our treatment strategy for this case was endovascular coiling.

Case report

A previously healthy 52-year-old man admitted to our emergency clinic with acute loss of consciousness complaint. His past medical history was not relevant with moyamoya or stroke. On neurological exam, he was confused and non-oriented. He had a left hemiparesis with three-fifths strength. Computed tomography scan revealed a diffuse intraventricular hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage (Figure 1). The patient underwent external ventricular drainage in emergency settings and further medical treatment continues in our neurointensive care unit (NICU).

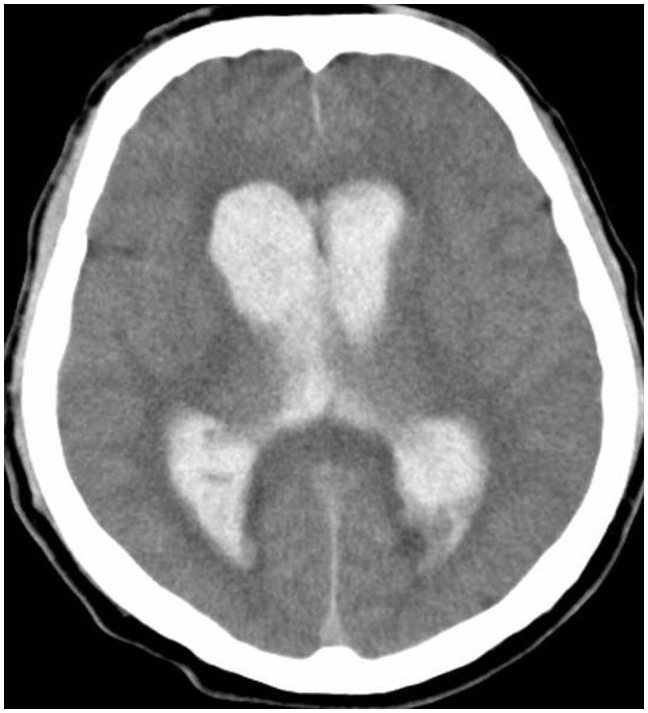

Figure 1.

Axial computed tomography showed diffuse intraventricular hemorrhage.

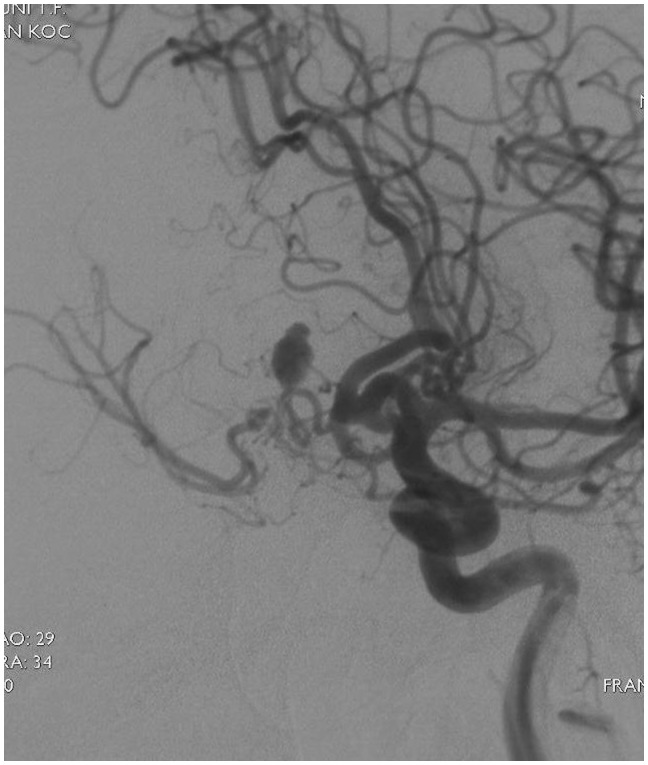

On the fifth day of admission the patient underwent cerebral angiography. Cerebral angiography revealed proximal occlusion of the right ICA after the anterior choroidal branch (Figure 2). A tangle of small caliber, tortuous arteries originating from the right anterior cerebral artery (ACA) reconstituted the M1 segment distally. In addition, posterior cerebral artery reconstituted the distal segments of middle cerebral artery (MCA) (Figure 3). The distal MCA and its branches had normal caliber and course. Left ICA angiography demonstrated normal left-sided vasculature with filling a collateral network via a patent ACA and anterior communicating artery. A 7.5 × 4 mm2, lobulated, saccular aneurysm with 0.5 mm size neck was seen inside the collateral network (Figure 4).

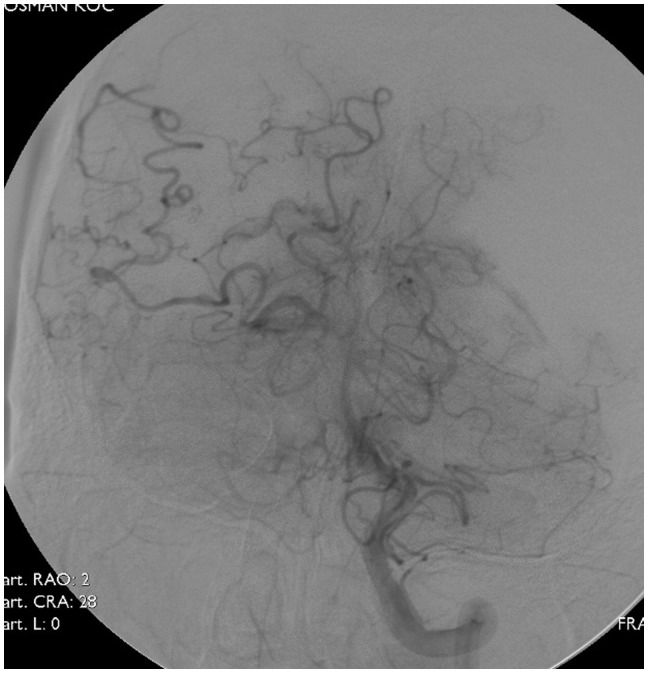

Figure 2.

Cerebral angiography showed proximal occlusion of the right ICA after the anterior choroidal branch.

Figure 3.

Collateral arteries originating from the right anterior and posterior cerebral artery.

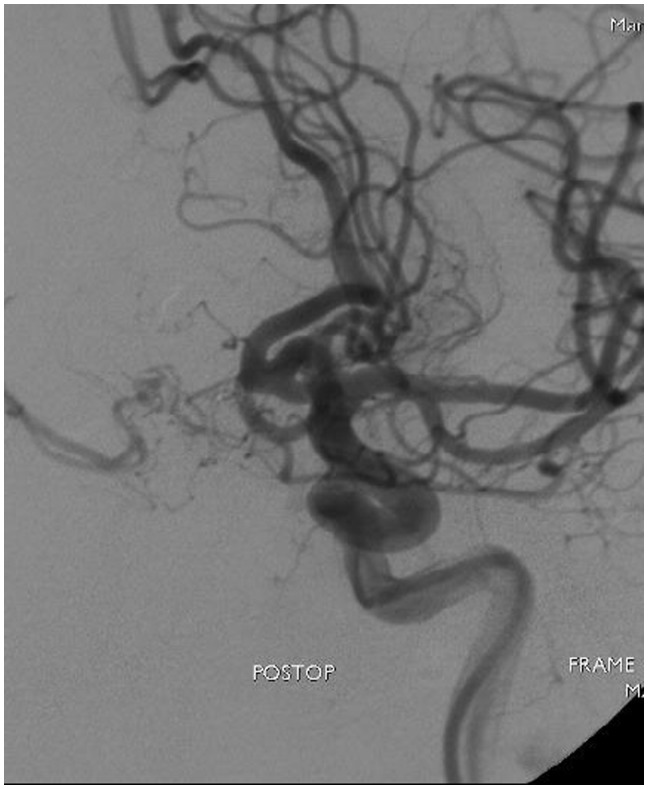

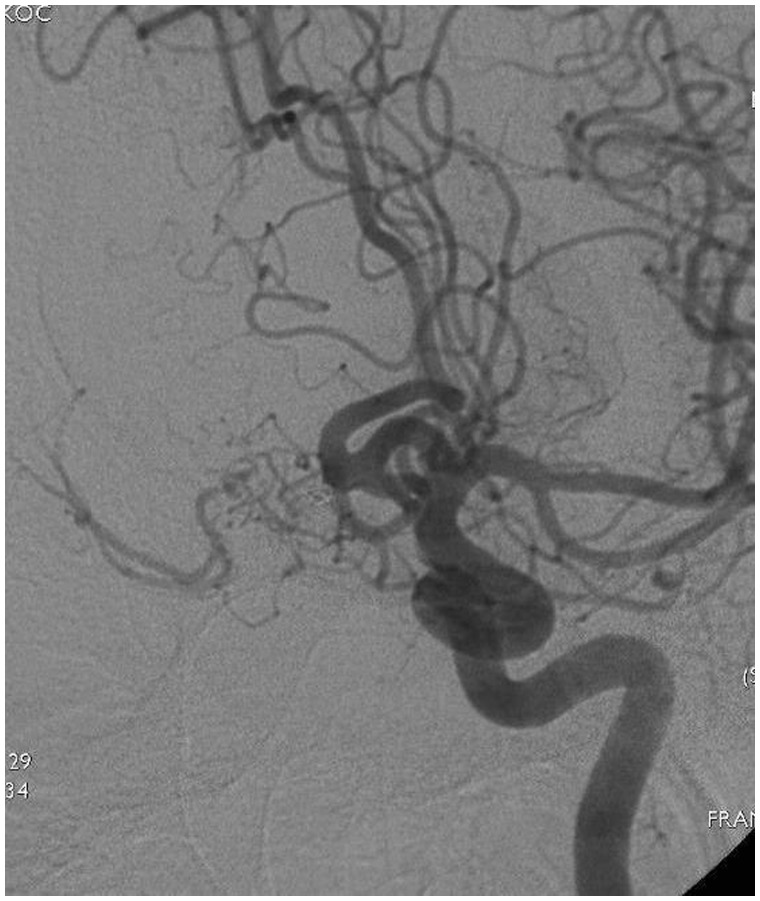

Figure 4.

Saccular aneurysm inside the collateral network.

On the seventh day of admission the patient underwent second cerebral angiography for the endovascular coiling. Under general anesthesia, a 6 Fr long vascular introducer sheath was placed in the right femoral artery, a 6 Fr Neuron™ guiding catheter (Penumbra®, California, USA) was inserted in the left internal carotid artery, and a microcatheter (Excelsior™ SL-10; Stryker, California, USA) was coaxially introduced proximal to the origin of the aneurysm. Due to narrow size of aneurysm neck and arterial tortuosity, intraluminal occlusion could not achieved and parent artery was occluded by using one microcoil (MicroPlex®, MicroVention, CA,USA). During the procedure, the patient received heparin with an activated clotting time maintained at 2–2.5 times baseline. The procedure was terminated successfully without any complication. Immediate post coil results showed total occlusion of the aneurysm (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Immediate post coil result.

The patient extubated 3 days after endovascular coiling, external ventricular drain removed and the patient discharged from NICU. Postoperatively, the patient's strength in the left upper and lower extremities improved with physical therapy, and he was discharge to a rehabilitation facility. Total occlusion of the aneurysm was seen at follow-up angiography after six months (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Six month control cerebral angiography showed the occlusion of aneurysm within the collateral network.

Discussion

We report the first case of collateral arterial network associated with spontaneous ICA occlusion. Spontaneous occlusion of the intracranial arteries, such as middle cerebral artery occlusion with moyamoya phenomenon, was previously described by Fukawa et al.2 An isolated M1 segment MCA occlusion and the absence of bilateral involvement differentiated this entity from moyamoya disease, and the lack of atheromatous plaques or stenosis in other cerebral arteries distinguished it from atheromatous occlusion.3 Fukawa et al. also showed the difference of this phenomenon from usual findings of moyamoya histopathologically in an autopsy case.2 This entity was considered as a congenital anomaly like duplicate, fenestrated, or accessory MCA and named as “twig-like” MCA.4 To our knowledge, spontaneous “non-moyamoya” internal carotid artery occlusion has never been reported before. Our patient was a previously healthy man with no previous ischemic or hemorrhagic cerebral disease. The occlusion was unilateral and any atheromatous plaques or stenosis in other cerebral arteries was not seen in angiography. Progressive occlusion of a major intracranial artery, independently from the etiology, can lead to the development of collateral arterial networks that supply blood flow to distal territories beyond the occlusion.1 These collateral arteries are typically small and conduct low flows, but the hemodynamic stress within them can lead to aneurysm formation within the collateral network.1

Various treatment strategies, including conservative treatment, trapping, bypass surgery, or clipping, were used for the treatment of these challenging aneurysms when they ruptured.1 Surgical treatment of ruptured aneurysms on collateral network contains difficulties due to their deep location and combined ischemic condition of the brain.5 The aneurysm in our case was located deeply and the parent collateral artery was very small. Therefore, our first choice for this case was endovascular coil embolization.

Conclusion

To our knowledge this is the first report about spontaneous ICA occlusion and collateral network aneurysm formation. Our treatment strategy for this case was endovascular coiling. Endovascular coiling may be a valid and safe alternative with low morbidity for the management of deep located, challenging collateral network aneurysms.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Rodríguez-Hernández A, Lu DC, Miric S, et al. Aneurysms associated with non-moyamoya collateral arterial networks: report of threecases and review of literature. Neurosurg Rev 2011; 34: 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukawa O, Aihara H, Wakasa H. Middle cerebral artery occlusion with moyamoya phenomenon – 2nd report: report of an autopsy case. No Shinkei Geka 1982; 10: 1303–1310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seki Y, Fujita M, Mizutani N, et al. Spontaneous middle cerebral artery occlusion leading to moyamoya phenomenon and aneurysm formation on collateral arteries. Surg Neurol 2001; 55: 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H-M, Lai D-M, Tu Y-K, et al. Aneurysm in twig-like middle cerebral artery. Cerebrovasc Dis 2005; 20: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SH, Kwon OK, Jung CK, et al. Endovascular treatment of ruptured aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm of the collateral vessels in patients with moyamoya disease. Neurosurgery 2009; 65: 1000–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]