Abstract

The classification of posterior fossa congenital anomalies has been a controversial topic. Advances in genetics and imaging have allowed a better understanding of the embryologic development of these abnormalities. A new classification schema correlates the embryologic, morphologic, and genetic bases of these anomalies in order to better distinguish and describe them. Although they provide a better understanding of the clinical aspects and genetics of these disorders, it is crucial for the radiologist to be able to diagnose the congenital posterior fossa anomalies based on their morphology, since neuroimaging is usually the initial step when these disorders are suspected. We divide the most common posterior fossa congenital anomalies into two groups: 1) hindbrain malformations, including diseases with cerebellar or vermian agenesis, aplasia or hypoplasia and cystic posterior fossa anomalies; and 2) cranial vault malformations. In addition, we will review the embryologic development of the posterior fossa and, from the perspective of embryonic development, will describe the imaging appearance of congenital posterior fossa anomalies. Knowledge of the developmental bases of these malformations facilitates detection of the morphological changes identified on imaging, allowing accurate differentiation and diagnosis of congenital posterior fossa anomalies.

Keywords: Posterior fossa anomalies, congenital posterior fossa abnormalities, embryology posterior fossa, development posterior fossa, imaging posterior fossa

Introduction

The development of the posterior fossa and its contents takes place during the process of ventral induction in embryogenesis.1,2 Several steps occur based on genetic and molecular pathways which result in the normal anatomical structures recognized on imaging. Errors and defects during the development of these structures will lead to congenital malformations of the posterior fossa, including the brainstem, cerebellum, and cranial vault.1

The classification of posterior fossa malformations has been a controversial topic. Recent advances in molecular genetics have allowed a new proposed classification by Barkovich et al. based on neuroimaging, developmental biology, and molecular genetics.3 This classification divides the pathologies into four groups in an attempt to organize the disorders for clinical understanding and guidance in research.3 However, malformations affecting the brainstem, cerebellum, and cranial vault can be analyzed from a radiological standpoint based on their distinctive anatomy and embryologic development. Understanding the development of the midbrain, cerebellum, and cranial vault is essential in the differentiation of these malformations and aids in the distinction of their typical radiological findings. The most commonly encountered abnormalities will be described in terms of their development, clinical features, and imaging findings.

The terms agenesis, aplasia, hypoplasia, and atrophy will be used throughout this paper and refer to the following definitions:

– Agenesis: complete absence of an organ due to absence of its primordial tissue

– Aplasia: presence of primordial tissue which never developed into its final mature organ

– Hypoplasia: histologically normal but incompletely developed primordial tissue

– Atrophy: decreased size and weight of a normally developed organ4

Development of the midbrain and hindbrain: The mesencephalon and rhombencephalon

The embryogenesis of the human brain is a complex process involving several stages and steps controlled by multiple cellular and molecular signal pathways with a genetic component.1–3,5 The development of the midbrain and hindbrain occurs during the process of ventral induction in the 5th to 10th weeks of gestation. Three primary cephalic vesicles—the prosencephalon, mesencephalon, and rhombencephalon—are formed after the closure of the neural tube.2,6 The cephalic, cervical, and pontine flexures bend the axis of the embryological central nervous system in the region of these vesicles. The middle vesicle, mesencephalon, and the caudal vesicle, the rhombencephalon, differentiate into structures of the midbrain. The rhombencephalon also differentiates into structures of the hindbrain.

As the pontine flexure develops, further division of the rhombencephalon into an upper and lower vesicle, the metencephalon and myelencephalon occurs. These structures will further develop into the pons and medulla oblongata, respectively.7 Continuous indentation by the pontine flexure results in widening and thinning of the roof plate and separation of the lateral walls of the hindbrain, giving the rhombencephalon its characteristic rhomboidal shape.8 The exposed floor plate represents the floor of the 4th ventricle (Figure 1).

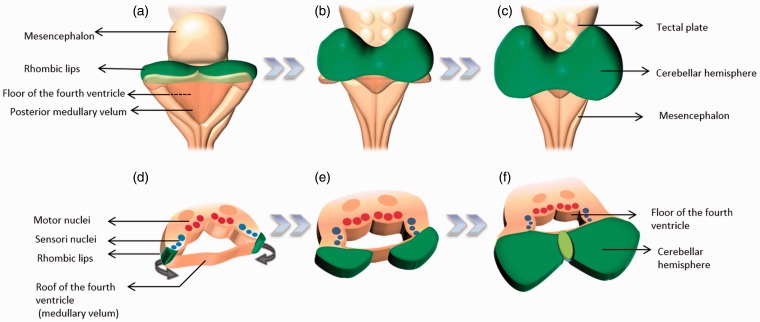

Figure 1.

(a, b and c) Representation of the differentiation of the ventral encephalic vesicles. The cephalic end of the neural tube demonstrates two constrictions that result in three vesicles. The most caudal vesicle (the rhombencephalon) will develop into the hindbrain. The rhombencephalon is divided into two vesicles (the metencephalon and myelencephalon). (d, e and f) The rhombic flexure causes the dorsal aspect of the neural tube to open, exposing the floor of the 4th ventricle with its characteristic rhomboidal shape, hence the name rhombencephalon.

At approximately the 10th week of gestation, tissue that will develop into the choroid plexus indents the thinned roof plate, which corresponds to the roof of the 4th ventricle. This indentation represents the plica choroidalis, and it divides the roof plate into a superior portion (the anterior membranous area) and an inferior portion (the posterior membranous area).3,7,9 The anterior membranous area will coalesce into the developing choroid plexus while the posterior membranous area is filled with cerebrospinal fluid and expands caudally, giving rise to a structure known as Blake’s pouch. Blake’s pouch will eventually permeabilize, and cerebrospinal fluid will accumulate in the space inferior to the cerebellum, resulting in the cisterna magna,7 which communicates freely with the 4th ventricle and spinal subarachnoid space. Blake’s pouch will then regress to result in the foramen of Magendie at the midline.7,9,10 The lateral angles of the newly formed rhomboid fossa will give rise to the Luschka foramina at a later stage, still unknown.11

The formation of the cerebellum ensues mainly from structures derived from the rhombencephalon, with the mesencephalon playing a role in the development of the vermis. During the 4th to 6th weeks of gestation, two areas of focal thickening are formed along the lateral edges of the roof plate, also known as rhombic lips. These differentiate into the cerebellar hemispheres as they enlarge and approximate each other in the midline, overlying the posterior aspect of the metencephalon and mesencephalon (Figure 2).7 The development of the vermis takes place in the 9th week as the cerebellar hemispheres form. Fusion between the developing cerebellar hemispheres occurs from cranial to caudal direction, forming the cerebellar vermis.12 Concomitantly, groups of neuronal tissue divided by grooves develop along the basal plate of the rhombencephalon by the end of the 4th week, and these later give rise to the nuclei for cranial nerves IV through XII, excluding the VIII cranial nerve. These foci of neuronal tissue represent the rhombomeres.8

Figure 2.

Posterior (a–c) and cross-sectional (d–f) representation of the brainstem showing the sequence of growth of the cerebellum from the rhombic lips (green). These develop along the lateral edges of the rhombencephalon and are the site of development of cerebellar differentiation.

Hindbrain malformations

The development of the cerebellum starts at the 4th week and gives rise to the vermis and paravermian hemispheres. The cerebellar hemispheres develop in the 5th week and continue to differentiate until the 2nd year of life. Most of the cerebellar dysgenetic abnormalities are believed to result from proliferation abnormalities and include cerebellar and pontine hypoplasias and dysplasias.3

Diseases with cerebellar or vermian agenesis, aplasia or hypoplasia

Cerebellar agenesis

Cerebellar agenesis is a very rare entity characterized by complete absence of the cerebellum. Malformative or disruptive causes should be considered when this entity is encountered. Recent genetic studies have described mutations in the PTF1A gene in chromosome 10, which result in the malformative phenotype of cerebellar agenesis.13 This gene is also linked to pancreatic development, hence, these patients present with permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus.13 Disruptive causes are more common and include cases in which normal development is truncated by extrinsic factors, including infections or vascular abnormalities.14

Small remnants of cerebellar tissue are usually identified on imaging in these cases, suggesting subtotal agenesis is the more proper term.15,16 Pontine hypoplasia is associated, as well as increased surrounding cerebrospinal fluid spaces within a normal-sized or enlarged posterior fossa.14,15 Total agenesis may be associated with other cerebral abnormalities including hydranencephaly and anencephaly.17 Cases of unilateral agenesis have been described and usually result in secondary contralateral hypoplasia of the pontine and inferior olivary nuclei16 with asymmetry of the pons, hypoplastic ipsilateral superior and middle cerebellar peduncles and superior colliculus, and hypoplasia of the contralateral substantia nigra and red nucleus.18 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the study of choice to demonstrate these findings, especially for the identification of cerebellar remnants, which could be very subtle (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cerebellar agenesis. (a) Sagittal T1WI, (b) axial T2WI and (c) coronal T2WI demonstrate absence of the cerebellum and significant hypoplasia of the pons (between arrows). Notice the downward herniation of the occipital lobes (arrowheads).

Patients have a variable clinical presentation, with delayed developmental milestones and problems with movement coordination. Truncal ataxia has been described when the cerebellar vermis is involved in cases of unilateral cerebellar hypoplasia.18 Although compensation by the cerebral cortex may delay the presentation or may cause some patients to be mostly asymptomatic,17 the cerebellar contribution in more complex cognitive functions may result in language, speech, affective, executive, and spatial cognitive impairment.18–20

Rhombencephalosynapsis

Rhombencephalosynapsis is a rare cerebellar anomaly in which aplasia or partial aplasia of the vermis coexists with various degrees of fusion of the cerebellar hemispheres, middle cerebellar peduncles, and dentate nuclei.21–23 The degree of vermian maldevelopment has been proposed to play a role in the classification of the severity of this entity. Partial absence of the nodulus and anterior and posterior vermis has been recognized as mild, while complete absence of the vermis, including the nodulus, has been defined as the most severe form.22

Characteristic features of rhombencephalosynapsis on MRI include fusion of the cerebellar hemispheres, visualized as continuous cerebellar white matter and folds across the midline, with various degrees of hypoplasia or aplasia of the vermis (Figure 4). These findings, along with fusion of the middle cerebellar peduncles and dentate nuclei, result in a characteristic diamond shape to the 4th ventricle.21,22 Pons hypoplasia has been described but occurs less commonly.22 Aqueductal stenosis commonly coexists with rhombencephalosynapsis, either alone (75% of patients) or in conjunction with hydrocephalus (65% of patients).23

Figure 4.

Rhombencephalosynapsis. (a) Axial T2, (b) sagittal T1 and (c) coronal FLAIR sequences show absence of the vermis with fusion of the cerebellar hemispheres (asterisk). The sagittal view shows the absence of a cerebellar vermis with a gray–white matter configuration similar to a cerebellar hemisphere. An interhemispheric cyst (arrow head) was present as an associated finding.

Associated findings, such as absence or hypoplasia of the septum pellucidum, dysgenesis or agenesis of the corpus callosum, and fusion of the anterior pillars of the fornix and thalami, may be present. Even though this syndrome’s etiology is unknown, the similarity of these associated findings suggest a shared developmental mechanism with holoprosencephaly,22 mostly involving the differentiation of the midline structures.7,23 Rhombencephalosynapsis may occur as an isolated anomaly, and in these cases patients may be asymptomatic.24 The association with VACTERL and Gomez–Lopez–Hernandez syndrome should prompt a complete clinical evaluation in patients in which rhombencephalosynapsis is diagnosed.23 In addition, careful evaluation of the cerebellum in cases of prenatal hydrocephalus should be pursued with prenatal ultrasound and MRI.25

Vermian–cerebellar hypoplasia

Vermian–cerebellar hypoplasia refers to varying degrees of incomplete development of the vermis and cerebellum.26 Genetic and metabolic causes have been described as causative agents of cerebellar hypoplasia, including trisomies 9, 13, and 18, disorders of glycosylation, migration disorders, congenital muscular dystrophies, and isolated genetic syndromes.14 Interference with normal development of the cerebellum by teratogenic drugs, including cocaine and anticonvulsant drugs, or infectious agents such as cytomegalovirus, can result in cerebellar hypoplasia as well.14 It is important to differentiate cerebellar hypoplasia from cerebellar atrophy since atrophy usually represents volume loss due to a progressive injury and not a real developmental anomaly. This differentiation is possible by the identification of normal-sized fissures relative to the folia27 (Figure 5) or by follow-up studies demonstrating stability of cerebellar hypoplasia rather than the progression expected with atrophy.14

Figure 5.

Cerebellar hypoplasia. (a) Sagittal T1WI and (b) axial T2WI show hypoplasia of the left cerebellar hemisphere (arrows), resulting in an enlarged surrounding subarachnoid space. Normal-sized fissures in relation to the folia are seen. A small cerebellar cleft is present in the left cerebellar hemisphere.

Imaging features of vermian–cerebellar hypoplasia include varying degrees of vermian and cerebellar hypoplasia within a normal-sized posterior fossa.26 A large 4th ventricle that communicates with the posterior cerebellar space by a passively widened vallecula is characteristic.14,26,28 Associated anomalies, such as a large cisterna magna and hydrocephalus, are often present.26,28 Other malformations such as migration abnormalities, meningoencephaloceles, agenesis of the corpus callosum, and holoprosencephaly have been observed, and their similarity with the Dandy–Walker malformation suggests a similar beginning within the developmental process (Figure 6).26,29

Figure 6.

Vermian-cerebellar hypoplasia. (a) Sagittal T1WI and (b) coronal T2WI show a prominent cystic space in the posterior fossa (asterisk) with a small cerebellum (arrows) and pons. The midbrain is elongated. Note associated agenesis of the corpus callosum along with ventricular dilatation.

Clinically, these patients present with hypotonia, abnormal ocular movements, and ataxia.28 Other findings such as delayed developmental milestones and intellectual disability are usually present but vary in severity.19,28

Lhermitte–Duclos disease

Lhermitte–Duclos disease, also known as dysplastic cerebellar gangliocytoma, is a rare lesion of the cerebellum characterized by distortion of the normal laminar pattern of the cerebellum.30 The pathogenesis and genetic causes are unknown. It is considered a benign hamartomatous neoplasm and is sometimes associated with Cowden syndrome.27,31

MRI is the study of choice in the evaluation of Lhermitte–Duclos disease. The classic findings include a non-enhancing striated mass in the posterior fossa with intercalated hyper- and hypointense bands on T1 and T2 sequences31 in a “corduroy pattern”. Associated mass effect over the 4th ventricle causes hydrocephalus, which then leads to the patient’s symptomatology (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Lhermitte–Duclos disease (dysplastic gangliocytoma). (a) Coronal FLAIR and (b) axial T2WI show increased signal of the left cerebellar hemisphere in a “corduroy pattern” with slight enlargement of the left cerebellar hemisphere (arrows). The 4th ventricle is small, appearing to be compressed by the lesion.

Clinical presentation varies from totally asymptomatic patients to those with symptoms associated with increased intracranial pressure, such as headache, blurry vision, and papilledema.31,32 Obstructive hydrocephalus is a frequent finding.

Walker–Warburg syndrome

Walker–Warburg syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive multisystem disorder characterized by eye and brain anomalies and congenital muscular dystrophy. The syndrome derives from defects in the O-glycosylation of alpha-dystroglycan (ADG),3,33,34 which is highly expressed in pial membranes and is also involved in cerebellar neuronal migration.33 Similar pathological phenomena with different intervening mutations have been described and result in other congenital muscular dystrophy variants including Fukuyama and muscle-eye-brain disease, which show various degrees of cognitive and morphologic abnormalities within the spectrum of Walker–Warburg syndrome.33

Imaging findings include type II cobblestone lissencephaly along the cerebral cortex and hydrocephalus. Abnormalities in the posterior fossa consist of cerebellar cortical cysts, polymicrogyria, and hypoplasia of the vermis, pons, and cerebellar hemispheres.33,35 A brainstem concavity at the floor of the 4th ventricle with a z-shape appearance of the midbrain on the sagittal sequences has also been described (Figure 8).33,35

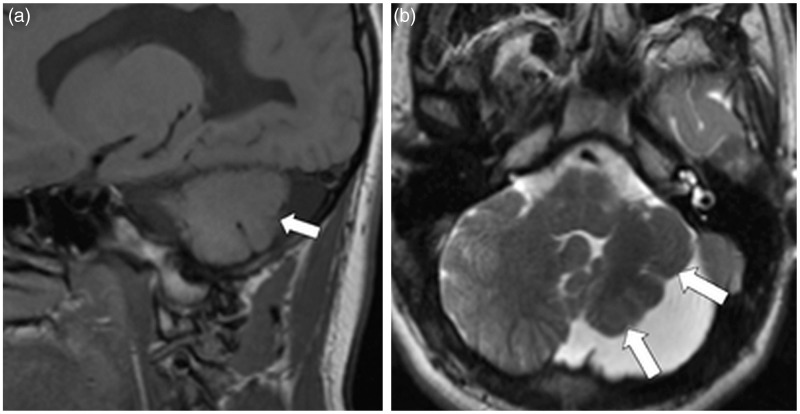

Figure 8.

Walker–Warburg syndrome. (a) Sagittal T1WI, (b) axial T2WI and (c) coronal T2WI show vermian hypoplasia with a prominent cerebrospinal fluid space (asterisk) elevating the torcula which communicates with the 4th ventricle. Migration anomalies with small white matter cysts in the cerebellum are demonstrated (black arrowheads). Brain type II lissencephaly is also present (white arrowheads). Note the “z”-shaped brainstem with concavity of the floor of the 4th ventricle, typical of Walker–Warburg syndrome.

Walker–Warburg syndrome is characterized by dystrophic changes in muscle, as well as hyperplastic primary vitreus, cataracts, microphtalmia, retinal detachment, and hypoplasia and/or atrophy of the optic nerve.35,36 Patients with this syndrome present with seizures and failure to reach developmental milestones. Most patients die by the third year of life.35,36

Joubert syndrome

Joubert syndrome represents a group of sporadic and autosomal recessive disorders that manifest clinically as ataxia, hypotonia, neonatal abnormal breathing, facial dysmorphism, and intellectual disability.37–40 Retinal dystrophy, nephronophthisis, hepatic fibrosis, and polydactyly may also be present.37 Several causal genes have been identified; all are associated with function of the primary cilia and basal body organelle, structures believed to play a role in signaling pathways during cerebellar development.41

The main features of Joubert syndrome are agenesis or dysgenesis of the vermis, a deep interpeduncular fossa and long, thick and horizontally oriented superior cerebellar peduncles that do not decussate.39,40 These findings produce the characteristic and pathognomonic “molar tooth sign” at the level of the ponto-mesencephalic junction on axial images.40,42 Sagittal MRI images consistently demonstrate vermis hypoplasia or dysplasia40 with a horizontally oriented 4th ventricle that remains open caudal to the tectum. Association with a posterior fossa cyst may occur in less than 25% of cases when complete agenesis of the vermis is present, often confusing the diagnosis (Figure 9).40,41 Other associated abnormalities in the central nervous system include hydrocephalus, enlargement of the posterior fossa, corpus callosum anomalies, hypothalamic hamartoma, absence of the pituitary gland, migration anomalies, and occipital encephalocele.40,41 Studies utilizing diffusion tensor imaging and tractography have demonstrated varying degrees of absence of decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncles and corticospinal tract, suggesting the implementation of this modality as an aid in the diagnosis.42

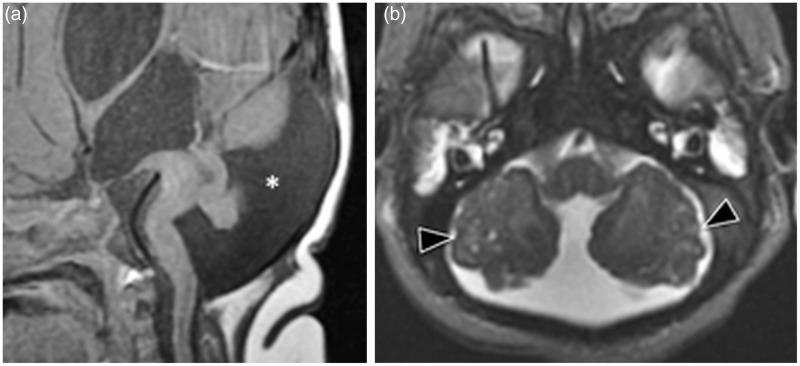

Figure 9.

Joubert syndrome. (a) Sagittal T1WI without contrast and (b) axial T2WI show vermian hypoplasia (arrowhead) and thickened superior cerebellar peduncles giving the “molar tooth” appearance (arrows).

Cystic posterior fossa anomalies

Cystic lesions include Dandy–Walker malformation, arachnoid cysts, and Blake’s pouch cysts. Most of these entities have been postulated to share a common origin in mesenchymal neuroepithelial signaling defects.3

Dandy–Walker malformation

Dandy–Walker malformation results from failure of integration of the anterior membranous area in the plica choroidalis. Cerebrospinal fluid pulsations7 cause the nonintegrated anterior membranous area to expand posteriorly within the posterior fossa,26 forming a large posterior cyst that represents the 4th ventricle.11,43 Since the membrane covers this posterior cyst, no communication with the subarachnoid space exists.

Hydrocephalus is present in up to 80% of classic Dandy–Walker malformation cases and is considered an associated complication rather than a malformation itself. Dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, brainstem dysplasias, aqueductal stenosis, migration anomalies, schizencephaly, lipomas, cephaloceles, and lumbosacral meningocele may be associated as well.43,44 Trisomies 13 and 18 and triploidy have been associated with the development of the Dandy–Walker malformation.45,46 Its occurrence has also been documented in other genetic conditions such as Walker–Warburg, Meckel–Grueber, Ritscher–Schnizel cranio-cerebello-cardiac, and PHACE syndromes, amongst others.5,7,16 In addition, extrinsic disruptions such as cytomegalovirus and rubella may play a causative role.16 Although up to 75% of patients have normal intelligence, the presence of hydrocephalus and associated cerebral anomalies determines the different degrees of cognitive outcomes.16 Hearing and visual disturbances as well as seizures have been described.16

Imaging findings demonstrate varying degrees of cerebellar vermis hypoplasia which consistently shows marked anterosuperior rotation.7 Enlargement of the posterior fossa with superior displacement of the transverse sinuses and torcula, as well as tilting of the cerebellum and tentorium is also seen (Figure 10).11,27 MRI is the modality of choice for the evaluation of these findings.7

Figure 10.

Dandy–Walker malformation. (a) Axial CT and sagittal T2WI images show a posterior fossa cyst (arrows) that communicates with the 4th ventricle and displaces the cerebellar hemispheres laterally. Hydrocephalus is present (asterisk). The vermis is small and tilted superiorly. The pons is also decreased in size.

Arachnoid cyst

Arachnoid cysts are benign leptomeningeal cysts that develop from separation or duplication of the arachnoid membrane, with subsequent filling of the superfluous arachnoid membrane with cerebrospinal fluid.7,47 Arachnoid cysts do not communicate with the ventricular system or surrounding arachnoid space and are usually incidental, asymptomatic malformations.7 They vary in location; however, up to two-thirds are found in the middle cranial fossa.47 They are rare in the posterior fossa, and when they occur in this location, they may mimic other posterior fossa cystic malformations. Arachnoid cysts are also seen in the sellar region and along the prepontine and interpeduncular cisterns.26,47

The clinical manifestations of posterior fossa arachnoid cysts vary according to the age of the patient and the size and amount of pressure that the cyst exerts upon the surrounding structures.26 Hemorrhage may cause an arachnoid cyst to expand, increasing its pressure, leading to acute symptomatology in adults. Fluid secretion from cyst wall cells, a ball-valve mechanism and osmotic changes may also cause cysts to expand.47 In children, cyst expansion may cause mass effect and hydrocephalus, resulting in enlarging head size and cerebellar compression symptoms.26,47

On imaging, arachnoid cysts are large cystic structures with well-defined, smooth margins. The cysts produce mass effect and displacement of the surrounding cerebellum26 without invasion,48 and may be associated with hydrocephalus. Pulsation may cause scalloping of the adjacent bone. Density measurements on computed tomography (CT) and signal intensity on MR are equal to cerebrospinal fluid unless complications such as hemorrhage or infection are present. Lack of communication with the ventricular system is characteristic (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Arachnoid cyst. (a) Sagittal T1WI shows a large cyst surrounding the cerebellum which displaces the corpus callosum superiorly (arrow). (b) Axial T2WI shows anterior displacement and mass effect against the cerebellum by the cyst (asterisk). The cerebellar falx is not seen at the midline (arrowhead).

Blake’s pouch cyst

Blake’s pouch cyst represents an embryologic abnormality of the posterior membranous area in which failure of regression of Blake’s pouch occurs secondary to non-fenestration involving the foramen of Magendie.10,49 Since the development of the foramina of Luschka occurs on a later stage, it allows the supratentorial and 4th ventricles to enlarge diffusely due to obstruction of flow at the larger foramen of Magendie. This enlargement cannot be compensated by the later opening of the foramina of Luschka.49 This cystic lesion represents an out-pouching of the 4th ventricle and does not communicate freely with the subarachnoid space,10,49 and causes mass effect over the surrounding structures. A key finding to differentiate this malformation from similar entities is the position of the choroid plexus within the 4th ventricle. In Blake’s pouch cyst, the choroid plexus curves under the vermis to lie within the cyst along its superior wall.7,49 In addition, diffuse hydrocephalus, including the involvement of the 4th ventricle, is key in the differentiation from posterior fossa arachnoid cysts, the latter showing obstruction at the level of the 4th ventricle due to compression.26,47,49

Clinical presentation is variable. Severe cases of intracranial hypertension have been described, usually related to complications within the cyst such as hemorrhage or infection.49 On the other hand, a number of patients may be asymptomatic or only show mild neurologic impairment; Blake’s pouch cysts in these patients are detected incidentally.49

MRI is the best imaging modality to identify this abnormality. A cystic collection of cerebrospinal fluid in the retro- or infracerebellar region that communicates with a distended 4th ventricle is characteristic.7,49 Mass effect on the surrounding cerebellar hemispheres and vermis may be present, but these structures are normal in morphology. Associated hydrocephalus may be seen.7,49 MRI with contrast can identify the choroid plexus along the superior wall of the cyst. Vermian hypoplasia, vermian tilting, and superior displacement of the torcula are not present, differentiating this entity from Dandy–Walker malformation (Figure 12).49

Figure 12.

Blake's pouch cyst. (a) Sagittal T1 with contrast and (b) axial T2WI show elevation of a normal vermis by a cystic lesion that extends from the 4th ventricle to the foramen magnum (asterisk); the 4th ventricle is enlarged. The choroid plexus is visualized along the superior aspect of the cyst (arrowheads).

Megacisterna magna

Although technically the megacisterna magna is not a cyst, it has a similar imaging appearance to the cystic posterior fossa anomalies described above and plays an important role as a differential diagnosis.

Megacisterna magna is a common abnormality of the posterior fossa characterized by abnormal widening of the cisterna magna with a normal-appearing cerebellar vermis and hemispheres. It is believed to occur due to late permeabilization of Blake’s pouch, which allows the pouch to enlarge and expand the posterior fossa before its fenestration.50 This results in a normal-sized 4th ventricle with free communication of the cisterna magna with the surrounding subarachnoid spaces.26 Generally, no hydrocephalus is present and most of the patients are asymptomatic.7

Important imaging features that differentiate this condition from other similar entities are: 1) a normal vermis containing nine lobules, which differentiates the condition from Dandy–Walker malformation and vermian-cerebellar hypoplasia,26 2) absence of hydrocephalus, which differentiates megacisterna magna from a persistent Blake’s pouch, and 3) lack of mass effect on the surrounding cerebellum and cerebellar falx, which differentiates the anomaly from an arachnoid cyst (Figure 13).7

Figure 13.

Megacisterna magna. (a) Sagittal T1WI and (b) axial T2WI show an abnormally widened cisterna magna in the posterior fossa (arrowheads). There is no compression or mass effect against the cerebellum. Note that the cerebellar falx is seen at the midline (arrows). The vermis and the 4th ventricle are normal in size.

Cranial vault malformations (chiari malformations)

Chiari malformations represent a group of abnormalities that affect the cranial vault as well as the posterior fossa contents. Traditionally, four types of Chiari malformations have been described. However, the Chiari IV malformation, characterized by cerebellar hypoplasia or aplasia and abnormalities in the pons,51 is now recognized within the cerebellar hypoplasia group.52

Protrusion of the cerebellar tonsils beyond the foramen magnum is the common finding in Chiari I, II, and III. Differences in the embryologic basis of these abnormalities explain the additional associated findings of each type; Chiari I malformations have been attributed to mesodermal defects, while types II and III derive from neuroectodermal derangements.51,53

Chiari I malformation

Chiari I malformations may be congenital or acquired. The congenital form is a developmental dysgenesis of the hindbrain in which inferior displacement of the cerebellar tonsils into the spinal canal through the foramen magnum is the most characteristic feature.54 Associated cervical syringomyelia has been documented in up to 56% of cases.54 A mesodermal defect involving sclerotomes implicated in the development of the occipital bone has been documented as a possible cause, resulting in an underdeveloped and small posterior fossa.55,56 It is important to differentiate this malformation from acquired Chiari I malformation, in which the herniation of the tonsils is due to intracranial hyper- or hypotension. This differentiation can be done on the basis of age at presentation (children and young adults in the congenital form) and posterior fossa volume (diminished in the congenital form, normal in the acquired form).52

Signs and symptoms of the Chiari I malformation are related to compression of the posterior fossa and spinal canal. Headache, often exacerbated by activities which increase intrathoracic pressure (coughing, laughing and exercising), and lower cranial nerve, cerebellar, and brainstem dysfunction are common.

MRI is the modality of choice in the evaluation of the Chiari I malformation because of its superiority at visualizing the craniocervical junction. Tonsillar herniation of 5 mm or more beyond the opisthion-basion line is diagnostic, but the malformation has been described in cases with only 3 mm herniation. The presence of associated syringomyelia may support the diagnosis in these cases.52,57,58 Scoliosis is a common finding when syringomyelia is present and is seen in up to 30% of cases (Figure 14).59 Other skeletal abnormalities include platybasia, basilar impression, craniosynostosis, and the Klippel–Feil syndrome.60,61

Figure 14.

Chiari I malformation: (a) Axial T2WI shows crowding at the level of the foramen magnum with herniation of the cerebellar tonsils (arrow). (b)Sagittal T1WI shows caudal herniation of the “peg shaped” cerebellar tonsils (arrow). (c) Sagittal T2WI of a different patient shows associated syringomyelia (arrowheads).

Chiari II malformation

Chiari II malformation represents a congenital hindbrain deformity characterized by inferior displacement of the cerebellum (mostly the vermis), medulla, and 4th ventricle into the spinal canal. A small posterior fossa, a lumbar myelomeningocele,52,61 and hydrocephalus are also associated.62 Many theories have been suggested to explain the basis of this malformation.52 A widely accepted theory proposes a defect of neuroectodermal origin as the cause: lack of occlusion of the neural tube results in leakage of fluid from the embryonic ventricular system, resulting in abnormal distention of the posterior fossa and the subsequent characteristic findings of this malformation.53,58,63

The most distinctive clinical feature of the Chiari II malformation is the presence of a lumbar myelomeningocele, an open spinal dysraphism, in a neonate. The presence of hydrocephalus manifests as an enlarging head. Patients are usually younger than 2 years of age and may require emergent neurosurgical decompression (Figure 15).64

Figure 15.

Chiari II malformation. (a)Sagittal T1WI shows a small posterior fossa with a low torcular insertion (arrow) and tectal beaking (arrowhead). (b) Axial T2WI fails to demonstrate the cerebellum between the occipital lobes. (c) T2WI shows spinal dysraphysm.

Typical findings of the Chiari II malformation on MRI include a small posterior fossa, inferior displacement of the cerebellar vermis and brainstem, and superior displacement of the cerebellum through the tentorial incisura (the so-called towering cerebellum).52,61 A characteristic kink of the medulla is seen above the posterior aspect of the spinal cord61 due to the attachment of the dentate ligament to the cord.52 The inferior displacement of the posterior fossa structures results in enlargement of the foramen magnum, inferior beaking of the tectum, and stretching of the 4th ventricle and aqueduct. The cerebellum may wrap around the pons. The lateral ventricles are frequently enlarged, especially posteriorly (colpocephaly). Other associated anomalies—such as agenesis or dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, migration anomalies, holoprosencephaly, and interhemispheric cysts—may be seen in up to 90% of cases.52,65 Absence of the cerebral falx is manifested by interdigitation of the cerebral gyri at the midline.

Chiari III malformation

The Chiari III malformation is the rarest type of Chiari malformation. It is characterized by intracranial features of the Chiari II malformation (small posterior fossa with inferior displacement of its contents) with an associated occipital or cervical spinal dysraphism through which the posterior fossa contents herniate, resulting in an encephalocele.52,66,67 A neuroectodermal defect similar to the defect involved in Chiari II may explain this abnormality.

Patients are usually identified at an early age by the presence of a cystic mass in the cervical or occipital region. Older patients will present with ataxia, hypotonia, and developmental delay.67,68 As with the Chiari II malformation, mass effect in the posterior fossa may lead to hydrocephalus and symptoms related to increased intracranial pressure, such as headache.

Imaging findings include a high cervical or occipital encephalocele with varying quantities of herniated cerebellar or even occipital tissue. Dysplasia, atrophy, and gliosis of the herniated contents are common.52 The spinal osseous defects primarily affect the posterior arch of C1;52,68 however, incomplete fusion of the posterior arches of other upper cervical levels may occur. The remaining imaging findings are identical to those found with the Chiari II malformation. As seen with the Chiari II malformation, agenesis or dysgenesis of the corpus callosum and syringomyelia are frequently associated abnormalities (Figure 16).52,67

Figure 16.

Chiari III malformation. (a)Sagittal T2WI, (b) axial T2WI and (c) coronal T2WI demonstrate an occipital encephalocele (arrows), an elongated appearance of the brainstem and descent of the cerebellar tonsils (arrowheads).

Summary

The interpretation of congenital anomalies of the posterior fossa is challenging. Recent classification schemas correlate the embryologic, morphologic, and genetic bases of these anomalies in order to better distinguish and understand them. Neuroimaging is often the initial and mandatory step in order to obtain a diagnosis when an abnormality is suspected, and this is when an imaging anatomical approach aids the interpretation (Figure 17). Nonetheless, a detailed comprehension of normal posterior fossa development and its derangements is also crucial. Understanding the embryologic origins of posterior fossa malformations eases recognition of the morphological changes identified on imaging and facilitates accurate diagnosis.

Figure 17.

A classification based on development alone is not possible. We have divided the most common posterior fossa anomalies based on their imaging morphology into two groups: 1) hindbrain malformations, including diseases with cerebellar or vermian agenesis, aplasia or hypoplasia and cystic posterior fossa anomalies; and 2) cranial vault malformations.

*not a true cystic lesion.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fotos J, Olson R, Kanekar S. Embryology of the brain and molecular genetics of central nervous system malformation. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2011; 32: 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volpe P, Campobasso G, De Robertis V, et al. Disorders of prosencephalic development. Prenat Diagn. 2009; 29: 340–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barkovich AJ, Millen KJ, Dobyns WB. A developmental and genetic classification for midbrain-hindbrain malformations. Brain J Neurol 2009; 132: 3199–3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goljan EF. Rapid Review Pathology: With Student Consult Online Access, 4e, Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donkelaar HJ, Lammens M, Wesseling P, et al. Development and developmental disorders of the human cerebellum. Neurology 2003; 250: 1025–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanekar S, Shively A, Kaneda H. Malformations of ventral induction. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2011; 32: 200–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shekdar K. Posterior fossa malformations. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2011; 32: 228–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Standring S. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 39th edition London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyberg DA, McGahan J, Pretorius DH, et al. Diagnostic Imaging of Fetal Anomalies, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manto MU, Pandolfo M. The Cerebellum and Its Disorders, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barkovich AJ, Kjos BO, Norman D, et al. Revised classification of posterior fossa cysts and cyst like malformations based on the results of multiplanar MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol 1989; 153: 1289–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estroff JA, Scott MR, Benacerraf BR. Dandy-Walker variant: Prenatal sonographic features and clinical outcome. Radiology 1992; 185: 755–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sellick GS, Barker KT, Stolte-Dijkstra I, et al. Mutations in PTF1A cause pancreatic and cerebellar agenesis. Nat Genet 2004; 36: 1301–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poretti A, Prayer D, Boltshauser E. Morphological spectrum of prenatal cerebellar disruptions. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2009; 13: 397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sener RN. Cerebellar agenesis versus vanishing cerebellum in Chiari II malformation. Comput Med Imaging Graph 1995; 19: 491–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niesen CE. Malformations of the posterior fossa: Current perspectives. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2002; 9: 320–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sener RN, Jinkins JR. Subtotal agenesis of the cerebellum in an adult. MRI demonstration. Neuroradiology 1993; 35: 286–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poretti A, Limperopolous C, Roulet-Perez E al. Outcome of severe unilateral cerebellar hypoplasia. Dev Med Child Neurol 2010; 52: 718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain 1998; 121: 561–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmahmann JD, Caplan D. Cognition, emotion and the cerebellum. Brain 2006; 129: 290–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Utsunomiya H, Takano K, Ogasawara T, et al. Rhombencephalosynapsis: cerebellar embryogenesis. Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19: 547–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishak GE, Dempsey JC, Shaw DW, et al. Rhombencephalosynapsis: A hindbrain malformation associated with incomplete separation of midbrain and forebrain, hydrocephalus and a broad spectrum of severity. Brain 2012; 135: 1370–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitehead MT, Choudhri AF, Grimm J, et al. Rhombencephalosynapsis as a cause of aqueductal stenosis: An under-recognized association in hydrocephalic children. Pediatr Radiol 2014; 44: 849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Justyna Paprocka EJ. Isolated rhomboencephalosynapsis - a rare cerebellar anomaly. Pol J Radiol Pol Med Soc Radiol 2012; 77: 47–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAuliffe F, Chitayat D, Halliday W, et al. Rhombencephalosynapsis: Prenatal imaging and autopsy findings. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008; 31: 542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kollias SS, Ball WS, Prenger EC. Cystic malformations of the posterior fossa: differential diagnosis clarified through embryologic analysis. Radiographics 1993; 13: 1211–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel S, Barkovich AJ. Analysis and classification of cerebellar malformations. Am J Neuroradiol 2002; 23: 1074–1087. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarnat HB, Alcalá H. Human cerebellar hypoplasia: A syndrome of diverse causes. Arch Neurol 1980; 37: 300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raybaud C. Cystic malformations of the posterior fossa. Abnormalities associated with the development of the roof of the fourth ventricle and adjacent meningeal structures. J Neuroradiol 1982; 9: 103–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cianfoni A, Wintermark M, Piludu F, et al. Morphological and functional MR imaging of Lhermitte-Duclos disease with pathology correlate. J Neuroradiol 2008; 35: 297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinagare AB, Patil NK, Sorte SZ. Case 144: Dysplastic cerebellar gangliocytoma (Lhermitte-Duclos disease) 1. Radiology 2009; 251: 298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klisch J, Juengling F, Spreer J, et al. Lhermitte-Duclos disease: Assessment with MR imaging, positron emission tomography, single-photon emission CT, and MR spectroscopy. Am J Neuroradiol 2001; 22: 824–830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clement E, Mercuri E, Godfrey C, et al. Brain involvement in muscular dystrophies with defective dystroglycan glycosylation. Ann Neurol 2008; 64: 573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muntoni F, Brockington M, Godfrey C, et al. Muscular dystrophies due to defective glycosylation of dystroglycan. Acta Myol 2007; 26: 129–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barkovich AJ. Neuroimaging manifestations and classification of congenital muscular dystrophies. Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19: 1389–1396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vajsar J, Schachter H. Walker-Warburg syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2006; 1: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maria BL, Quisling RG, Rosainz LC, et al. Molar tooth sign in Joubert syndrome: Clinical, radiologic, and pathologic significance. J Child Neurol 1999; 14: 368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Millen KJ, Gleeson JG. Cerebellar development and disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2008; 18: 12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pugash D, Oh T, Godwin K, et al. Sonographic ‘molar tooth’ sign in the diagnosis of Joubert syndrome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 38: 598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poretti A, Huisman TA, Scheer I, et al. Joubert syndrome and related disorders: Spectrum of neuroimaging findings in 75 patients. Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 1459–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doherty D. Joubert syndrome: Insights into brain development, cilium biology, and complex disease. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2009; 16: 143–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poretti A, Botlshauser E, Loenneker T, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in Joubert Syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 1929–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson M, Maher K, Gilles FH. A different approach to cysts of the posterior fossa. Pediatr Radiol 2004; 34: 720–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riascos R and Bonfante E. RadCases Neuro Imaging. Thieme Publishers, October 2010. ISBN-13: 978-1604061895.

- 45.Kölble N, Wisser J, Kurmanavicius J, et al. Dandy-Walker malformation: Prenatal diagnosis and outcome. Prenat Diagn 2000; 20: 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imataka G, Yamanouchi H, Arisaka O. Dandy-Walker syndrome and chromosomal abnormalities. Congenit Anom 2007; 47: 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gosalakkal JA. Intracranial arachnoid cysts in children: A review of pathogenesis, clinical features, and management. Pediatr Neurol 2002; 26: 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osborn AG, Preece MT. Intracranial cysts: Radiologic-pathologic correlation and imaging approach. Radiology 2006; 239: 650–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cornips EM, Overvliet GM, Weber JW, et al. The clinical spectrum of Blake’s pouch cyst: Report of six illustrative cases. Childs Nerv Syst 2010; 26: 1057–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robinson AJ, Goldstein R. The cisterna magna septa vestigial remnants of Blake’s pouch and a potential new marker for normal development of the rhombencephalon. J Ultrasound Med 2007; 26: 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schijman E. History, anatomic forms, and pathogenesis of Chiari I malformations. Childs Nerv Syst 2004; 20: 323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kanekar S, Kaneda H, Shively A. Malformations of dorsal induction. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2011; 32: 189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rollins N, Joglar J, Perlman J. Coexistent holoprosencephaly and Chiari II malformation. Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20: 1678–1681. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elster AD, Chen MY. Chiari I malformations: Clinical and radiologic reappraisal. Radiology 1992; 183: 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marin-Padilla M, Marin-Padilla TM. Morphogenesis of experimentally induced Arnold–Chiari malformation. J Neurol Sci 1981; 50: 29–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nishikawa M, Sakamoto H, Hakuba A, et al. Pathogenesis of Chiari malformation: A morphometric study of the posterior cranial fossa. J Neurosurg 1997; 86: 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barkovich AJ, Wippold FJ, Sherman JL, et al. Significance of cerebellar tonsillar position on MR. Am J Neuroradiol 1986; 7: 795–799. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mikulis DJ, Diaz O, Egglin TK, et al. Variance of the position of the cerebellar tonsils with age: Preliminary report. Radiology 1992; 183: 725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steinbok P. Clinical features of Chiari I malformations. Childs Nerv Syst 2004; 20: 329–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ball WS, Jr, Crone KR. Chiari I malformation: From Dr Chiari to MR imaging. Radiology 1995; 195: 602–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.el Gammal T, Mark EK, Brooks BS. MR imaging of Chiari II malformation. Am J Roentgenol 1988; 150: 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolpert SM, Anderson M, Scott RM, et al. Chiari II malformation: MR imaging evaluation. Am J Roentgenol 1987; 149: 1033–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McLone DG, Knepper PA. The cause of Chiari II malformation: A unified theory. Pediatr Neurosci 1989; 15: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stevenson KL. Chiari Type II malformation: Past, present, and future. Neurosurg Focus 2004; 16: E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wong SK, Barkovich AJ, Callen AL, et al. Supratentorial abnormalities in the Chiari II malformation, III: The interhemispheric cyst. J Ultrasound Med 2009; 28: 999–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hadley DM. The Chiari malformations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72(Suppl 2): ii38–ii40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cakirer S. Chiari III malformation: Varieties of MRI appearances in two patients. Clin Imaging 2003; 27: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ambekar S, Devi BI, Shukla D. Large occipito-cervical encephalocele with Chiari III malformation. J Pediatr Neurosci 2011; 6: 116–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]